on

3 years on Google App Engine. An Epic Review.

For the last 3 years I worked on an application that runs on Google App Engine. It is a fascinating, unique piece of service Google is offering here. Unlike anything you’ll find elsewhere. This is my in-depth, personal take on it.

Google’s Cloud (est. 2008)

First of all, what is Google App Engine (GAE) actually? It is a platform to run your web applications on. Like Heroku. But different when you look closer. It is also a versatile cloud computing platform. Like AWS. But different. Let me explain.

Google launched GAE in 2008, when cloud computing was still in its infancy. Amazon was ahead of them since they already started renting out their IT infrastructure in 2006. But with GAE, Google offered a sophisticated Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS) very early on that would be matched by Amazon with its Elastic Beanstalk service in 2011. Now what is so special about GAE?

It is a fully-managed application platform. So far, I do not know a platform which comes close to GAE’s full package: log management, mail delivery, scaling, memcache, image manipulation, distributed Cron jobs, load balancing, version management, task queue, search, performance analysis, cloud debugging, content delivery network - and that is not even mentioning auxiliary services that have popped up on Google’s cloud in the meantime like SQL, BigQuery, file storage… the list goes on.

By using Google App Engine, you can run your app on top of (probably) the world’s best infrastructure. Also, you receive functionality out of the box that would take at least a dozen add-ons from third parties on Heroku or a few weeks of setup if done on your own. This is GAE’s appeal.

Noteworthy applications that run on GAE include Snapchat and Khan Academy.

Development

The web app I was working on all this time is a single, large Java application. App Engine also supports Python, PHP and Go. Now you might wonder why the selection is so limited. One reason is that in order to have a fully-managed environment, Google needs to integrate the platform with the environment. You could say that environment and platform are tightly coupled. That takes a lot of effort and investment which becomes very clear once you start developing for GAE.

SDK

Each app needs to use a special SDK (Software Development Kit) to use the APIs offered by GAE. The SDK is huge. For example, the Java SDK download comes in at roughly 190 MB. Granted, some of the JARs in there are not needed for most use cases and some only during development - but still, it certainly is not lightweight (even for Java, that is).

The SDK is not just your bridge to the world of Google App Engine but also serves as its simulation on your local machine. For virtually every GAE API it features a stub that you can develop against. First of all, this means that when you run your app locally you’ll get quite close to how it would behave in production. Second of all, you can easily write integration tests against the APIs. And usually this will get you very far; the mismatch between the production and stub behavior is quite small.

Java APIs

Speaking of APIs, you are in for a surprise when you use certain Java APIs. Since GAE runs your application in some kind of sandbox, it forbids using particular Java APIs. The major restrictions include writing to the file system, certain methods of java.lang.System and using the Java Native Interface (JNI). There are also peculiarities about using threads and sockets but more on that later.

One interesting thing is that the Java SDK actually ensures you do not use these restricted APIs locally. When you run your app or just an integration test, it employs a Java agent that monitors your every method call. It immediately throws an exception for any detected violation. This is helpful in finding violations early and not only in production but has an annoying side effect. When you profile the performance of your app, there will be an overwhelming amount of violation checks by the agent. In the end, it is hard to judge your app’s actual performance since the more method calls you make, the more overhead the agent generates.

Java Development Kit (JDK)

The next thing you might notice when you start developing is that you can not use Java 8. Even though Java 7’s end of life was in 2015, it is still very much alive and kicking on GAE. The third highest voted issue on GAE’s issue tracker is support for Java 8 (the second highest is support for Python 3). It was created in 2013. Since then, the only shred of news about any progress on the matter is a post on the App Engine mailing list from 2016, stating engineers are actively working on it. Well, good for you.

Obviously, this limitation is a major annoyance for any developer. For me personally, the missing lambda support weighs very heavily. Of course, one could migrate to one of the many JVM languages like Groovy, Scala or Kotlin which all offer a lot more features than Java 8. But this is a costly and risky investment to make. Too costly and risky for our project. We also investigated the feasibility of retrolambda, a backport of lambdas to Java 7, but did not pursue it yet although it looked promising in first tests.

Having to stay with an old version is also a liability for the business. It makes it harder to find developers. Overall application security is threatened, as well. Google support told us, we would still receive security patches for our production JDK 7. But eventually, all major libraries like Spring will stop supporting it. Eventually, you’ll be stuck.

Deployment

To deploy your application, you need to create an appengine-web.xml configuration file. There, you specify the application ID and version plus some additional settings, e.g. marking the app as threadsafe to be able to receive multiple requests per instance simultaneously.

Upload

App Engine expects to receive your Java application as a packaged WAR file. You can upload it to their servers with the appcfg script from the SDK. Optionally, there are plugins for Maven and Gradle which make this as easy as writing mvn appengine:update. The upload can take quite a while for typical Java applications, you’d better have a fast internet connection. Once the process finishes, you can see your newly deployed version in the Google Cloud Console:

Static Files

Static files like images, stylesheets and scripts are part of any web application today. In the appengine-web.xml files can be marked as static. Google will serve these files directly - without hitting your application. It is not exactly a Content Delivery Network (CDN) since it is not distributed to hundreds of edge nodes, but it helps to reduce the load on your servers.

Versions

The nice thing in App Engine is that everything you deploy has a specific version. Every version can be accessed at https://<version>-dot-<app-id>.appspot.com. But which one is actually live?

You can mark a version as default. This means when you go to https://<app-id>.appspot.com (or the domain name you specified for the app), that will be the version receiving all the requests. Switching a version to default is very easy: all it takes is a button click or simple terminal command. GAE can switch immediately or migrate your traffic incrementally to prevent overwhelming the new version.

There is also one option (which we never used) that allows you to distribute your traffic across multiple versions. This allows incrementally rolling out a new version by only giving it to a fraction of the user base before making it available for everyone.

Since it is so easy to create new versions and switch production traffic between them, GAE is a perfect platform to practice blue-green deployment. Each time we had the need to rollback due to a bug in the new version, it was effortless. Continuous Delivery should also be achievable by writing a somewhat smart deployment script.

Instances

Every version can run any number of instances (the only limit is your credit card). The actual number is the result of incoming traffic and the scaling configuration of your app; we’ll look at that later. Google will distribute incoming requests between all running instances of that version. You can see a list of instances, including some basic metrics like requests and latency, in the Google Cloud Console:

The hardware options you can choose from to run these instances on are - let’s be frank here - pathetic. App Engine basically offers four different instance classes ranging from 128MB and 600MHz CPU (you read that correctly) to 1024MB and 2.4GHz CPU. Yes, again, that is true. And truly sad. On a developer’s laptop our app started almost twice as fast as in production.

Services

So far, I have only talked about a single, monolithic application. But what do you do if yours consists of multiple services? App Engine has got you covered. Every app is a service. If you only have one, it is simply called default. You can access each one directly via https://<version>-dot-<service>-dot-<app-id>.appspot.com.

You can easily deploy multiple versions of each service, scale and monitor them separately. And since each service is separate from the others, you could run any combination of the supported languages. Unfortunately though, some configuration settings are shared across all services. They are therefore not perfectly isolated. Still, all in all, GAE seems like a good fit for microservices. There is some elaborate documentation on this topic from Google, as well.

For reasons that will become clear later, we decided to separate our application into two services: frontend (user-facing) and backend (background work). But to do so, we didn’t actually split the monolith in two - that would have taken months. We simply deployed the same app twice and only sent users to one service and background work to the other.

Operations

Let’s talk about what it means to run your application on App Engine. As you will see, there are a number of restrictions it imposes on you. But it is not all gloomy. In the end you will understand why.

Application Startup

When App Engine starts a new instance, the app needs to initialize. It will either directly send the HTTP request from the user to the app or - if the configuration and scaling circumstances allow it - send a so-called warmup request. Either way, the first request is called a loading request. And as you can imagine, starting quickly is important.

The instance itself on the other hand is ridiculously fast to start. If you have started a server in the Cloud before, you might have waited more than a minute. Not on GAE. Instances start almost instantly. I guess Google holds a pool of servers ready to go. The bottleneck will always be your own app. Our application took more than 40 seconds to start in production. So unless we wanted to split our huge monolith into separate services, we needed it to start more efficiently.

The app uses Spring. Google even has a dedicated documentation entry just for that: Optimizing Spring Framework for App Engine Applications. There we found the inspiration for our most important startup optimization.

We got rid of Spring’s classpath scanning. It is particularly slow on App Engine (probably due to the abysmal CPU). Luckily, there is a library called classindex. It writes the fully qualified path of classes with a special annotation to a text file. By simply reading the beans from the text file, the Spring initialization went down by about 8-10 seconds.

Request Handling

The very first thing I have to mention here is the requirement of the App Engine to handle a user request within 60 seconds and a background request in 10 minutes. When the application takes too long to respond, the request is aborted with a 500 status code and a DeadlineExceededException is thrown.

Usually, this shouldn’t be a problem. If your app takes more than 60 seconds to respond, odds are the user is long gone anyway. But since an instance is started via an HTTP request, this also means it has to start in 60 seconds. In production, we observed variations in startup time of up to 10 seconds. This means you now have less than 50 seconds to start your app. It is not uncommon for a Java app to take that long.

One nice little feature I’d like to highlight is the geographical HTTP headers: for each incoming user request, Google adds headers that contain the user’s country, region, city as well as latitude and longitude of said city. This can be very useful, for example for pre-filling phone number country codes or detecting unusual account login locations. The accuracy also seems pretty high from our observations. It is usually very cumbersome and/or expensive to get that kind of information with this level of accuracy from a third party API or database. So getting it for free on App Engine is a nice bonus.

Background Work

Threads

As mentioned earlier, there are restrictions using Java threads. While it is possible to start a new thread, albeit through a custom GAE ThreadManager, it cannot ‘outlive’ the request it was created in. This can be annoying in practice since third party libraries don’t follow App Engine’s restrictions, of course. To find a compatible library or adapt a seemingly incompatible one, cost us a lot of sweat and tears over the years. For example, we could not use the Dropwizard metrics library out of the box since it relies on using a background thread.

Queue

But there are other ways of doing background work: In the spirit of the Cloud, you apply the divide and conquer approach on the instance level. By using task queues you can enqueue work for later processing. For example, when an email needs to be sent, you can enqueue a new task with a payload (e.g. recipient, subject and body) and a URL on a push queue. Then, one of your instances will receive the payload as a HTTP POST request to the specified endpoint. If it fails, App Engine will retry the operation.

This pattern really shines when you have a lot of work to process. Simply enqueue a batch of tasks that run in isolation. The App Engine will take care of failure handling. No need for custom retry code. Just imagine how awkward it would be without it: running hundreds of tasks at once you either need to stop and start from scratch when an error occurs or carefully track which have failed and enqueue them again for another attempt.

And just like the rest of the App Engine, task queues scale beautifully. A queue can receive virtually unlimited tasks. The downside is the payload can only be up to 1 MB, though. But what we usually did was to simply pass references to data to the queue. But then, you need to take extra good care in your data handling since it can easily happen that something vanishes between the time you enqueue a task and the time that task is actually executed.

The queues are configured in a queue.xml file. Here is an example of a push queue that fires up to one task per second with a maximum of two retries:

<queue>

<name>my-push-queue</name>

<rate>1/s</rate>

<retry-parameters>

<task-retry-limit>2</task-retry-limit>

</retry-parameters>

</queue>

Cron

Another extremely valuable tool is the distributed Cron. In a cron.xml you can tell GAE to issue requests at certain time intervals. These are just simple HTTP GET requests one of your instances will receive. The smallest interval possible is once per minute. It is very useful for regular reports, emails and cleanups.

This is what an entry in cron.xml looks like:

<cron>

<url>/tasks/summary</url>

<schedule>every 24 hours</schedule>

</cron>

A Cron job can also be combined with pull queues: they allow to actively fetch a batch of tasks from a queue. Depending on the use case, making an instance pull lots of tasks in a batch can be much more efficient than pushing them to the instance individually.

Like all other App Engine configuration files, the cron.xml is shared across all services and versions of an application. This can be annoying. In our case, sometimes when we deployed a version where a new Cron entry had been added, App Engine would start sending requests to an endpoint which did not exist on the live (but older) version - generating noise for our production error reporting. I imagine this must be even more painful when using App Engine to host microservices.

Also, the Cron jobs are not run locally. I can understand why that might be: a lot of the jobs are usually scheduled outside the usually busy time and would therefore not even be triggered during a regular workday. But some run like every few minutes or hours - and those are really interesting to observe. They might trigger notifications, for example. You want to see those locally. Because eventually you will introduce a change that leads to undesirable behavior (as has happened multiple times in our project) and seeing it locally might prevent you from shipping it. But simulating the Cron jobs locally is tricky (we didn’t bother, unfortunately). One would probably need to write an external tool that parses the cron.xml and then pings the according endpoints (yuck!).

Scaling

App Engine will take care of scaling the number of instances based on the traffic. How? Well, depending on how you have configured your application. There are three modes:

- Automatic: This is GAE’s unique selling point. It will scale the number of instances based on metrics like request rate and response latency. So if there is a lot of traffic or your app is slow to respond, more instances spin up.

- Manual: Basically like your good old virtual private servers. You tell Google how many instances you want and Google delivers. This fixed instance size is useful if you know exactly what traffic you are going to get.

- Basic: Essentially the same as manual scaling mode but when an instance becomes idle, it is turned off.

The most useful and interesting one here certainly is the automatic mode. It has a few parameters that help to shed some light on how it works internally: max_concurrent_requests, max_idle_instances, min_idle_instances and max_pending_latency. To quote the App Engine documentation:

The App Engine scheduler decides whether to serve each new request with an existing instance (either one that is idle or accepts concurrent requests), put the request in a pending request queue, or start a new instance for that request. The decision takes into account the number of available instances, how quickly your application has been serving requests (its latency), and how long it takes to spin up a new instance.

Every time we tried to tweak those numbers, it felt like practicing black magic. It is very difficult to actually deduce a good setup here. Yet, these numbers determine the real-world performance of your app and hugely affect your monthly bill.

But all in all, the automatic scaling is pretty wicked. It is an especially good fit for handling background work (e.g. generating reports, sending emails) since it often - more so than user requests - comes in large, sudden bursts.

But the thing is, Java is a terrible fit for this kind of auto scaling due to its slow startup time. What makes matters worse, it is very common for the scheduler to assign a request to a starting (cold) instance. Then, all efforts that went into sub-second REST responses go out the window. Since 2012 there is an issue about user-facing requests never to be locked to cold instances. It has not even elicited the slightest comment by Google other than the status change to ‘Accepted’ (sounds like one of the stages of grief at this point).

This also explains why we split our app into two services. Before, we often found that with a surge in background requests, the user requests would suffer. This is because App Engine scaled the instances up immensely and, since requests are routed evenly across instances, this led to more user requests hitting cold instances. By splitting the app we significantly reduced this from happening. Also, we were able to apply different scaling strategies for the two services.

One last thing: In a side-project, I used Go on App Engine and discovered a new perspective on the App Engine. Among Go’s traits is the ability to start an application virtually instantly. This makes App Engine and Go a perfect combination, like Batman and Robin. Together, they embody everything I personally expected from the Cloud ever since I learned about it. It truly scales to the workload and does so effortlessly. Not even the abysmal hardware options seemed to pose a real problem for Go since it is that efficient.

Data

When App Engine launched, the only database options you had were Google Datastore for structured data and Google Blobstore for binary data. Since then, they have added Google Cloud SQL (managed MySQL) and Google Cloud Storage (like Amazon’s S3) which replaced the Blobstore. From the beginning App Engine offered a managed Memcache, as well.

It used to be very difficult to connect to a third-party database since you could only use HTTP for communication. But usually databases require raw TCP. This has only changed a few years ago when the Socket API was released. But it is still in Beta, which makes it a questionable choice for mission-critical usage. So database-wise, there is still very much of a vendor lock-in.

Anyway, in the beginning, there was only the Datastore.

Datastore

The Datastore is a proprietary NoSQL database, fully managed by Google. It is unlike anything I had ever used before. It is a massively scaling beast with very unique traits, guarantees and restrictions.

In the early days, the Datastore was based on a master-slave setup which featured strongly consistent reads. A few years in, after it had suffered a few severe outtakes, Google introduced a new configuration option: High Replication. The API stayed the same but the latency for writes increased and some reads became eventual consistent (more on that later). The upside was the significantly increased availability. It even has a 99.95% uptime SLA. Since I worked with it, I never experienced a single issue with the Datastore’s availability. It was just something you did not have to think about.

Entities

The basics of the Datastore are simple. You can read and write entities. They are categorized under a particular kind. An entity consists of properties. A property has a name and a value which has a certain type. Like string, boolean, float or integer. Each entity also has a unique key.

Writing

There is no schema whatsoever, though. Entities with the same kind can look completely different. This makes development very easy: just add a new property, save it and it will be there. The flip side is that you will need to write custom migration code to rename properties. The reason for this is that an entity cannot be updated in place - it must be loaded, changed and saved again. And depending on the volume of entities, this can become a non-trivial task since you might need to use the task queue to circumvent the request time requirements. In my experience, this leads to old property names all over the place since refactoring is so costly and dangerous.

There are a some limits for working with entities. The two most critical are:

- An entity may only be 1MB in total, including additional meta data of the encoded entity

- You can only write to an entity (group, to be exact) up to once per second

In practice, this can be an issue. We rarely hit the size limit - but when we did, it was painful. Customer data can get lost. When you hit the write rate limitation, it is usually fine on the next try. But of course you have to design your application to minimize the odds of that. For example, something like a regularly updated counter takes a lot of work to get right. Google even has a documentation entry on using sharding to build a counter.

Reading

An entity can be fetched by using its key or via a query. Reads by key are strongly consistent, meaning you will receive the latest data even if you updated the entity right before fetching it. However, this is not true for queries. They are eventually consistent. So writes are not always reflected immediately. This can lead to problems and might need to be mitigated, for example by clever data modelling (e.g. using mnemonic as key) or leveraging special Datastore features (e.g. entity groups).

A query always specifies an entity kind and optional filters and/or sort orders. Every property that is used in a filter or as a sort key must be indexed. Adding an index can only be done as part of the regular write operation. Not automatically in the background as in most SQL databases. The index will also increase the time of the write operation and the cost (more on that later).

If a query involves multiple properties, it requires a multi-index. It must be specified in a configuration file called datastore-indexes.xml. Here is an example:

<datastore-index kind="Employee" ancestor="false">

<property name="lastName" direction="asc" />

<property name="hireDate" direction="desc" />

</datastore-index>

In contrast to other databases, the absence of a multi-index will not just result in an inefficient, slow query - it will fail immediately. The Datastore tries its very best to enforce performant queries. Inequality filters, for example, only support a single property. Of course, there are always ways to shoot yourself in the foot - but they are rare.

There are several other features I cannot go into now, for example pagination, projection queries and transactions. Go to the Datastore documentation to learn more, it is very extensive and helpful.

Compared to other databases the read and write operations are very slow. Based on my observations, a read by key takes 10-20ms on average. It is rare to see significant deviations. My best guess is that Google serializes entities and only indexes are actually kept in memory.

The pricing model seems to support that: you pay for stored data, read, write and delete operations. That’s it. Note that database memory is not in that list. The operations themselves are cheap as well: reading 100k entities costs $0.06, 100k write operations cost $0.18 - a write operation can be the actual entity write but also every index write. If you don’t write anything, you don’t pay anything. But in a single minute you could be writing gigabytes of data. And here’s the kicker: The read and write performance is basically the same for a database with no entities or a billion. It scales like crazy.

API

The API to the Datatore feels very low-level. Therefore, for any serious Java app there is no way around Objectify. It is a library written by Jeff Schnitzer. If Google has not done so already, they should write him a huge cheque for making the App Engine a better place. He wrote it for his own business but the tireless dedication over the years, extensive documentation and support he offers in forums is astounding. With Objectify, working with the Datastore is actually fun.

Here is an example from the documentation:

@Entity

class Car {

@Id String vin;

String color;

}

ofy().save().entity(new Car("123123", "red")).now();

Car c = ofy().load().type(Car.class).id("123123").now();

ofy().delete().entity(c);

Objectify makes it really easy to declare entities as simple classes and then takes care of all the mapping between the Datastore.

It also has a few tricks up its sleeve. For example, it comes with a first-level cache. This means that whenever you request an entity by key, it first looks into a request-scoped cache whether the entity was already fetched. This can be beneficial for improving performance. However, it can also be confusing because when you fetch an entity and modify it but do not save it, the next read will yield that same cached, modified object. This can lead to Heisenbugs.

Development & Testing

Since the App Engine is a proprietary cloud database, you cannot just start it locally. When you run your application on your machine, a mock Datastore is started by the SDK. Its behavior comes very close to the production environment. Only the performance is much better, which can be misleading.

For running tests against the Datastore, the SDK is also able to start a local Datastore for you. However, this must be a different implementation since it behaves differently than the one for running the app. This becomes apparent when you realize that a missing multi-index will throw an error when executing the app locally but not when testing the same query. Over the years I accidentally released several queries with missing indexes into production (usually still behind a Beta toggle) - although I had a test for it. After contacting support they admitted the oversight and promised to fix it - more than one year later they still have not.

Backups

Making backups of the Datastore is an atrocious process. There is a manual and an automatic way. Of course, when you have a production application, you’d like to have regular backups. The official way is a feature introduced in 2012 which is still in Alpha!

By adding an entry to your cron.xml you can initiate the backup process. The entry will include the names of the entities to backup as well as the Google Cloud Storage bucket to save them to. When the time has come, it will launch a few Python instances with the backup code, iterate through the Datastore and save them in some kind of proprietary backup format to your bucket. Interestingly, a bucket has a limit of how many files it can contain, so you better use a new bucket now and then.

This is the absolute worst thing about the Datastore.

Memcache

The other crucial way to store data on App Engine is Memcache. By default, you get a shared Memcache. This means, it works on a best-effort basis and there is no guarantee how much capacity it will have. There is also the dedicated Memcache for $0.06 per GB per hour.

Objectify is able to use this as a second-level cache. Just annotate an entity with @Cache and it will ask Memcache before the Datastore and save every entity there first. This can have a tremendous effect on performance. Usually Memcache will respond within about 5 ms, which is much faster than the Datastore. I am not aware of any stale cache issue we might have had. So this works very well in production.

The benefits of it are actually very noticeable when Memcache is down. This happened to us about once a year for an hour or two. Our site was barely usable, it was that slow.

Big Query

BigQuery is a data warehouse as a service, managed by Google. You import data - which can be petabytes - and can run analyses via a custom query language.

It integrates somewhat well with the Datastore since it allows to import Datastore backup files from Google Cloud Storage. I have used this a few times, unfortunately not always successfully. For some of our entities I received a cryptic error. I was never able to figure out what went wrong. But some entities did work. And after fiddling with the query language documentation for a bit, I was able to generate my first insights. Everything considered, it was a nice way to run simple analyses. I definitely would not have been able to do this without writing custom code. But I was not really leveraging the service’s full potential. All the queries I made could have been done in any SQL database directly, our data set was quite small. Only because of the way the Datastore worked did I have to resort to the BigQuery service in the first place.

Monitoring

The Google Cloud Console brings a lot of features to diagnose your app’s behavior in production. Just look at the Google Cloud Console navigation:

This is the result of Google’s acquisition of Stackdriver in 2014. It still feels like a separate, standalone service - but its integration into Google Cloud Console is improving.

Let’s look at the capabilities one by one.

Logging

It is crucial to access an application’s logs quickly and with ease. This is something that was truly painful on App Engine in the beginning. It used to be very cumbersome because it was incapable of searching across all versions of an application. This meant when you were looking for something, you had to know which version was online at the time - or try several, one by one. It was almost unusable. Plus it was extremely slow.

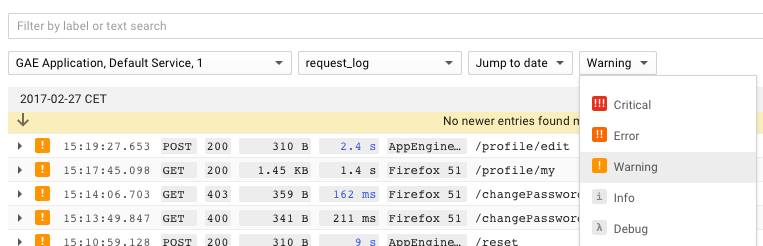

Since then, they have added useful filters to show only specific modules, versions, log levels, user agents or status codes. It is very powerful. Still not fast, but it has gotten much better now compared to the early days. Here is how it looks:

One very unique idea you can see here is that logs are always grouped by request. In all other tools I have encountered, Kibana for instance, you will only get the log lines that match your search. By always showing all other log lines around the one that matches your search, it gives you more context. I find this extremely helpful when investigating issues in the logs since it immediately helps you to better understand what happened. I truly miss that feature in every other log viewer I use.

Another interesting trait of the App Engine is that each HTTP request is automatically assigned a request ID. It is added to the incoming HTTP request and uniquely identifies it. This can come in handy to correlate a request with its logs. For example, we were sending emails when an uncaught exception occurred and included the request ID - this made it trivial to look up the logs. The same can be done for frontend error tracking.

Metrics

The Cloud Console gives access to a few basic application metrics. This includes the request volume and latency, traffic volume, memory usage, number of instances and error count. It is useful as a starting point when investigating an issue and when you want to get a quick first impression of the general state of the app.

Here is an example with the app’s request volume:

Tracing

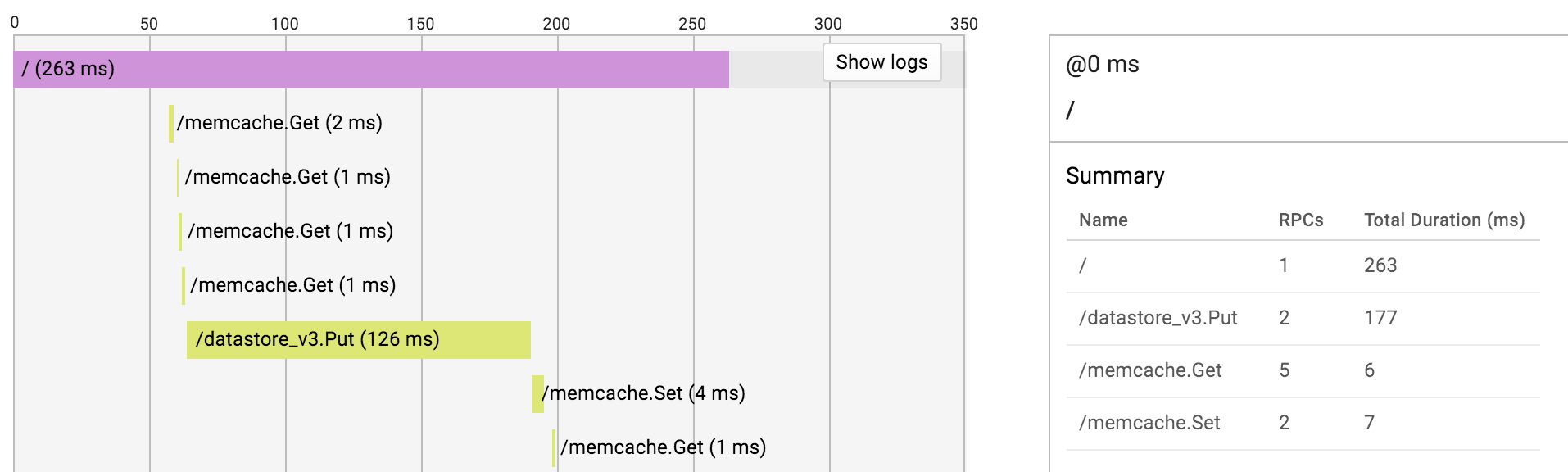

Since the App Engine instance is a black box, you cannot use other tools to diagnose its performance. If the logging console is not enough, the Trace page provides more detailed data. It allows to search for the latency distribution of certain requests.

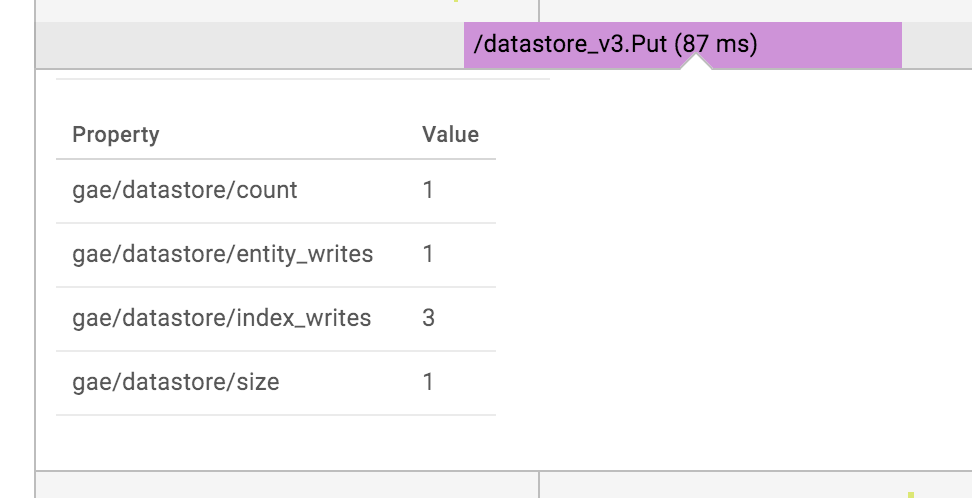

When you select a specific request, it opens up a timeline. There it displays the remote procedure calls (RPCs) that you cannot see in the logs. Plus, a summary for each RPC by type on the side. By clicking on an RPC, more details, e.g. the response size, are shown.

This can be extremely helpful to find the cause of a slow request. In the following example you can see that the request makes a few fast Memcache calls and a very slow Datastore write operation.

The only problem is that the RPCs do not include enough information to figure out what happened exactly. For instance, the detail view of the Datastore write operation looks like this:

It does not even include the name of the updated entity. This is a huge annoyance and can render this whole screen almost useless. There is just one thing which can help: clicking the ‘Show logs’ button in the upper right corner. It will include the log statements of the request inline interleaved with the RPCs. This way you might be able to infer more details from the context.

Resources

It is also important to point out that pricing is completely usage-based. This means the cost of your app scales virtually byte by byte, hour by hour and operation by operation. It also means, that it is very affordable to get started. There is no fixed cost. If hardly anyone uses your app - since there is a free quota - you do not pay anything.

The biggest item on the bill will most certainly be for the instances, contributing about 80% in my last project. The next big chunk is likely the Datastore read/write cost, 15% of the total cost for us.

There is a nice interface in the Google Cloud Console to keep track of all quotas:

To be more specific, when I say ‘all quotas’ I mean all quotas Google tells you about. We actually had an issue where we hit an invisible quota. I think at the time the API may have been in Beta, though. Anyway, one part of our application stopped working and we had no idea why. Luckily, we were subscribed to Google Cloud Support. They informed us about said quota and we had to rewrite a part of our application to make it work again.

We also had one minor outage due to the confusing pricing setup. At one point one of our apps suddenly stopped working and just replied with the default error page. It took us ten minutes to figure out that we hit the budget limit we had set up. After we raised it, everything just started working again.

Support

There is a lot to be said about Google Cloud Support. First of all, without it we would have been in serious trouble now and then. So having it is a must for any mission-critical application - in my eyes. For example, about once a year our application would just stop serving requests. There was nothing we did to cause that. After contacting Google support we would learn that they moved our application to a ‘different cluster’. And it just worked again. It is a very scary situation. You cannot do anything but ‘pray to the Google gods’.

Second of all, it is a hit or miss based on the support person. The quality varied a lot. Sometimes we would need to exchange a dozen messages until they finally understood us. Like any support it can be infuriating. But in the end, they would usually resolve our issue or at least give us enough information to help us resolve it ourselves.

A New Age

Google is working on a new type of App Engine, the flexible environment. It is currently in Beta. Its goal is to offer the best of two worlds: the ease and comfort of running on App Engine combined with the flexibility and power of Google Compute Engine. It allows to use any programming platform (like Java 9!) on any of the powerful Google Compute Engine machines (like 416GB RAM!) while letting Google take care of maintaining the servers and ensuring the app is running fine.

They have been working on this for some years already. Naturally, we were keen on trying it out. So far, we weren’t that thrilled. But let’s see where Google is taking this.

Design for Scale

Now, you can look at the restrictions the App Engine imposes on your app as annoyances. But bear with me for a moment. App Engine was created by Google. These guys know how to build scalable systems. The restrictions are merely a necessity. They force you to adapt your app to the ways of the Cloud. This is a good thing and should be embraced. If you feel like you are fighting the App Engine, then you are fighting against the ‘new’ rules of the Cloud. This is certainly one lesson I’m taking away from three years on Google App Engine.

Some restrictions and annoyances are the result of neglect by Google, though. It feels like they only invest the bare minimum anymore. Actually, I have had this feeling for the last two years. It is frustrating to work with an ancient tech stack, without any hope of improvement in sight. It is infuriating if there are known issues but they are not fixed. It is depressing to receive so little information on where the platform is heading. You feel trapped.

All in all, I liked how App Engine allowed the development team to focus on actually building an application, making users happy and earning money. Google took a lot of hassle out of the operations work. But the ‘old’ App Engine is on its way out. I do not think it is a good idea to start new projects on it anymore. If App Engine Flexible Environment on the other hand can actually fix its predecessor’s major issues, it might become a very intriguing platform to develop apps on.

comments powered by Disqus