Abstract

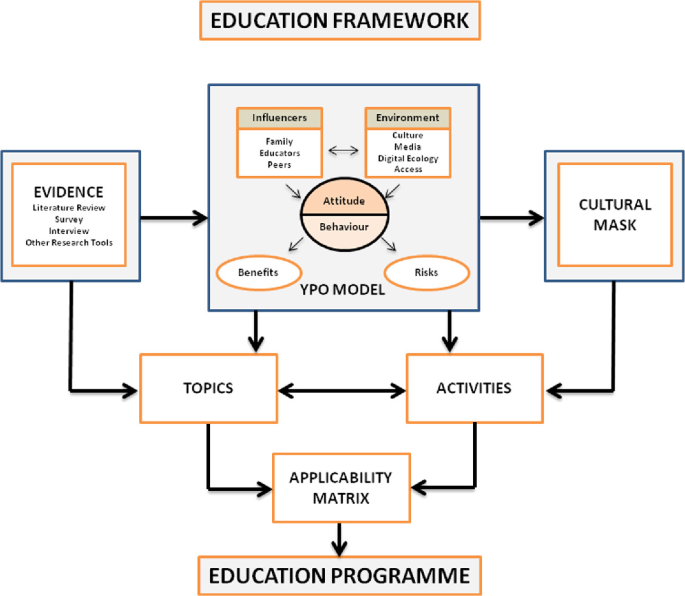

The majority of online safety awareness education programmes have been developed in advanced countries and for the needs of their own populations. In less developed countries (LDCs) not only are there fewer programmes there is also a research gap in knowing the issues that face young people in their respective country. The Young People Online Education Framework seeks to address this and provide educators, researchers and policy makers an evidence driven construct for developing education programmes that are informed by issues affecting young people in that particular country/region. This is achieved by following the steps within the framework starting first from the evidence stage, gathering the data and conducting new research if necessary. This is fed into the Young People Online Model, which looks at the environmental and social influences that shape young people’s attitude and behaviour online. A novel feature of this framework is the Cultural Mask, where all topics, activities and pedagogical approaches are considered with the cultural makeup of the target audience in mind. The framework was applied in Thailand and a number of workshops were successfully carried out. More research and workshops are planned in Thailand and it is hoped other researchers will make use of the framework to extend its scope and application.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

A little-explored area of online safety awareness education is the role of culture and specifically cultural differences which can lead to very different learning outcomes. Gasser, Maclay and Palfrey Jr. [5] note that:

“the most glaring gap in the research landscape … [is that] most of the relevant research (with a small number of important exceptions) has focussed on safety implications of Internet usage of young people in industrialized nations, usually with emphasis on Western Europe and Northern America. Despite recent efforts … much less is known about digital safety risks to children in developing and emerging economies.”

One of the reasons for this is that there is a, “lack of research and locally-relevant data … [and] policies are developed based on assumptions or on research that may not be locally applicable” [16]. In recognising this, Livingstone, Byrne and Bulger [14] argue that, “adapting research instruments designed in the global North to Southern contexts is challenging, and requires considerable sensitivity to the local circumstances of children’s lives, as well as sustained dialogue with the stakeholders who will use the research findings.” This sensitivity extends to the classroom and the cultural context of learners. Hall [6] asserts that:

“each culture is not only an integrated whole but has its own rules for learning. These are reinforced by different patterns of over-all organizations. An important part of understanding a different culture is learning how things are organized and how one goes about learning them … the reason one cannot get into another culture by applying the ‘let’s-fit-the-pieces-together’ is the total complexity of any culture.”

This paper puts forward an education framework that incorporates culture as an essential component for designing education programmes in less developed countries (LDCs); a term that will be used to represent the myriad other terms such as, ‘developing’, ‘emerging’ and ‘global South’. Correspondingly, in place of, ‘industrialized nations’ and ‘global North’ this paper addresses them as ‘advanced countries’. The next section discusses the background to this research and related works. Section 3 then introduces the education framework followed by how it was applied in the case study country, Thailand in Sect. 4. Finally, Sect. 5 is the conclusion and a discussion of future work.

2 Background and Related Work

The Young People Online (YPO) education framework formed the basis of a five year PhD study researching effective online safety awareness in LDCs. As stated above much of the existing research has taken place in advanced countries. One of the most influential is the Kids Online project which started as a European study to investigate and provide data for policy makers, educators and other researchers on the online experience of young people in Europe. Since its first report in 2006 it has morphed into the Global Kids Online (GKO) project which as the name suggest is a worldwide endeavour. At the time of writing there are ongoing studies in several countries including the following LDCs; Argentina, Brazil, Bulgaria, Chile, Ghana, the Philippines, South Africa and Uruguay. At their website, http://globalkidsonline.net they share project results and their research tools including survey questions.

The GKO research model has been developed over several iterations and now focuses on digital rights and well-being [15]. For the purposes of the YPO education framework it was deemed sufficient at this nascent stage to look at the risks and benefits of being online. This is the YPO model and is an integral part of the education framework as can be seen below in Fig. 1.

Both models are influenced by Bronfenbrenner’s ecological approach [7, 15]. Urie Bronfenbrenner worked in the field of developmental psychology and introduced the concept of encircling layers of influence with the child at the centre. The first layer includes the child’s immediate environment with parents/guardians, family, peers, teachers. The next layer includes the interactions of institutions and the indirect influence on the child including their; school, parents’ workplace, hospital and place of worship. Enveloping all this is the social and cultural layer, that is, the influence of the wider societal environment [7].

In the YPO model, Bronfenbrenner’s system is represented by the Influencers, family, educators and peers and the Environment, culture, media, digital ecology and access. The Influencers have a direct affect that helps to shape the personality, attitude and behaviour of the young person. For Thailand, it was necessary to conduct original research to obtain the relevant data as there were very few existing in-country studies to draw upon and therefore a mixture of surveys (a quantitative method) and interviews (a qualitative method) were undertaken. This mixed methods approach was deemed prudent as, “both forms of data provide a better understanding of a research problem than either quantitative or qualitative data by itself” [2].

2.1 Theory of Culture

To understand better the cross-cultural nature of the education framework theories of culture were investigated. In particular, the iceberg model of culture inspired by the work of Edward T. Hall and his seminal work, ‘Beyond Culture’ [6]. It recognises that each country has their own set of norms and values. At the surface culture level you have the visible signs of a culture like clothes, food and music. This is the etiquette layer where you can learn the dos and don’ts of a particular culture. For example, in Thailand, as in some other South East Asian countries, you should never touch a person’s head.

The shallow culture level includes non-verbal forms of communications, cues and gestures like, how to greet a person and timekeeping. This is the values or understanding layer. You know, for example, that you should not touch a person’s head because in Buddhism it is the highest part of the body and considered sacred. The feet are the lowest part of the body and considered dirty so you should never point them at another person. At the deep culture level, “understanding reality of covert culture and accepting it on a gut level comes neither quickly nor easily, and it must be lived rather than read or reasoned” [6]. This is the empathy or sensitivity layer. At this point you would not even contemplate touching another person’s head as it would just not feel right.

High-Context vs Low-Context.

Hall distinguished between cultures where context and protocol are central with those where what is said explicitly is more important. Deng [3] as cited in Knutson et al. [13] explains that:

“individualistic, or low-context cultures indicate a preference of direct and overt communication style, confrontational and aggressive behaviors, a clear self identification, and a priority of personal interest and achievement. Collectivistic, or high-context, cultures manifest a preference of indirect and covert communication style, an obedient and conforming behavior, a clear group identification, and a priority of group interest and harmony.”

Hofstede’s Dimensions of Culture.

Geert Hofstede introduced his four dimensions of culture (later expanded to six) after analysing data from 72 countries which included 116,000 employees between the years 1967–1973 [4]. The original four are:

-

Measure of individualism: Whether a culture leans to individualistic values or collectivistic ones.

-

Power distance: Measures how hierarchical or unequal a society is. Stricter hierarchical structures tend to have greater adherence to authority.

-

Measure of Masculinity (and femininity): Not to be confused with male and female. Masculine attributes include; assertiveness, toughness, competitiveness and materialism. Feminine attributes include; modesty, tenderness and quality of life over materialism. Gender roles in masculine cultures are clearly defined whereas in feminine cultures they overlap (Hofstede et al. 2010).

-

Uncertainty avoidance: This is, “the extent to which the members of a culture feel threatened by ambiguous or unknown situations” [10]. Cultures that exhibit high uncertainty avoidance are more likely to have and adhere to rules and regulations.

By understanding and utilising Hall’s high-context, low-context concept and Hofstede’s dimensions of culture a country profile can be prepared for the LDC. It should be noted that this cultural analysis can be conducted in any country. However, there are already online safety awareness education initiatives in advanced countries whereas there is a dearth of them in LDCs. It could still be a good exercise if it was applied to an education initiative aimed at a particular cultural group within an advanced country.

The next section introduces the education framework and a discussion of its component parts.

3 Young People Online Education Framework

One of the main objectives for the Young People Online study was to develop an integrative security education framework for online safety awareness in LDCs. In order to achieve this, different types of educational approaches were investigated. The framework is not solely theoretical. The Kids Online model aims to provide data for use by policy makers, researchers and educators. The YPO framework seeks to do the same and in addition offers practical solutions in the form of topics and activities that can be used by educators.

By working through the education framework the intention is to end up with an evidence based and locally relevant programme which will give it a better chance of success than just transposing one from another country.

Evidence:

The first component of the framework is the evidence stage. A literature review should be undertaken to investigate the state of existing research and education programmes pertaining to the LDC. If there is insufficient data then new research should be undertaken and wherever possible with stakeholders, including; the government, education authorities, educators, NGOs and interested researchers. Depending on the LDC this process can take some time. A number of factors can influence the data collection phase including the; political climate, socio-economic considerations, the technological infrastructure and geographical considerations. Once the data is collected it is fed into the second component which is the Young People Online (YPO) model.

Young People Online Model:

As noted above, the YPO model is influenced by the Kids Online model and Bronfenbrenner’s ecological approach. The YPO model can take a significant amount of time and resources to accomplish. However, once the process is worked through a picture can be formed on the online attitude and behaviour of young people online including; how they access content, from where they do so, what activities are most prevalent and especially important what potentially harmful behaviour they are exposed to.

This information is then used to create a list of topics and influence the type of activities to include in an education programme or initiative.

Cultural Mask:

A common definition of a mask is, “a piece of cloth or other material, which you wear over your face so that people cannot see who you are, or so that you look like someone or something else” (https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/mask). Within the YPO education framework the cultural mask concept can be seen in two ways.

Firstly, culture is a mask that can hide a visitor from what is really going on and this in turn can lead to misunderstandings. Hall illustrates this point with an experience he had as an American in Japan. After being at a particular hotel for several days he returned, asked for his key and went up to his room only to find that someone else’s things were in there. He went back to reception and they explained that he had been moved to another room. It was not until a few years after the first incident that a Japanese friend explained the reason behind this. When you check-in at the hotel you not only become a guest but a family member. With family, rules are a little more informal and relaxed so being moved from one room to another is a sign that you have been afforded this high status. This is almost opposite to the way he thought he was being treated.

Secondly, the cultural mask within the framework can be used as a filter. When designing an education programme the teaching approach you take, the topic(s) and activities included should be seen through the lens of the cultural mask.

Topics:

The online safety topics that make it into the education programme will come from the evidence stage and by working through the YPO model.

Activities:

In each LDC activities should be piloted to find out its appropriateness and effectiveness. This is achieved by a combination of action research (e.g. workshops) and desktop research on effective pedagogical approaches. Table 1 gives an example of one such activity.

Applicability Matrix:

The applicability matrix is a set of readymade activities, categorised to their appropriateness in different settings. It provides educators and researchers tried and tested activities that they can add to their programme. In addition, they can add their own activities and therefore increase the choice for others as well. Table 1 gives an example activity within the applicability matrix:

4 A Case Study in Thailand

The YPO Education Framework was applied to Thailand. During the initial stage of evidence gathering it became clear that there were few research studies concerning online safety. Therefore surveys were carried out in schools in the North East of Thailand [8]. Figure 2 below shows the combined result. In total, 352 students from five schools took part in the survey. What it found is that although the students are from a semi-rural area of Thailand, 9 out of 10 owned their own smartphone and girls slightly more than boys. Facebook and Facebook Messenger is the dominant social network and chat app respectively and along with playing online games and watching videos forms the basis of their digital lives. In terms of negative experiences 7 out of 10 had been upset by an online interaction with cyber-bullying identified as the main issue with 55% reporting it. Interestingly, 41% admitted to bullying behaviour. Other significant risks were exposure to sites discussing; committing suicide, self harm, drugs, sexual content, promotion of eating disorders and hate messages aimed at particular groups and individuals. In addition 1 in 5 had sent a photo or a video to someone that they had not met offline.

4.1 Cultural Context

Thailand, as pointed out above is a high-context country. In Hofstede’s cultural dimensions analysis this translates to being collectivistic on the measure of individualism. For each dimension an index of 0 to 100 was created measuring the differences between countries. Figure 3 below shows the scores for Thailand and the US, the latter an example of a low-context country. Unsurprisingly, the US scores high on individualism and masculinity In contrast, Thailand scores low in both indicating its collectivistic and feminine nature. Thailand scores higher than the US in power distance meaning it is a much more hierarchical society and also in the uncertainty avoidance index which tends towards more bureaucratic cultures with more rules and regulations. It also affects education where, “high uncertainty avoidance can also result in a preference for structured learning situations in the classroom” [4].

Hofstede’s dimensions of culture: a comparative between Thailand and the US (Data from Wilhelm & Gunawong [17])

4.2 Culture in the Classroom

A literature review was carried out on theories of culture and specifically on Thai culture and how it manifests itself within the education realm. Thailand is a hierarchal country with the king and the royal family at the top. Hierarchy is present in the classroom too with the teacher as the authority figure and the student there to receive knowledge. It is one reason why the traditional rote learning style still prevails. Thai teachers have high status but they are also responsible for the success or otherwise of their students. If a student fails in a test it is the fault of the teacher for not adequately preparing them for it. For a student to contradict or argue with a teacher would mean the latter losing face. Openly criticising a student causing them to lose face would also make everyone feel uncomfortable. This behaviour is anathema to Thai’s collectivistic nature where social harmony is a core characteristic. This is in part to Thais being overwhelming Buddhists. They practice, Theravada Buddhism which, “is a philosophy, a way of life and a code of ethics that cultivate wisdom and compassion” [1].

Kainzbauer and Hunt [12] investigated foreign teachers in Thailand and found that the successful ones had adapted to the classroom culture. This is encapsulated by the approach one teacher took:

“You never say ‘you have screwed up’; you may say ‘oh boy, did we screw up, didn’t we? … maybe I did not show you what I really wanted, therefore you could not really give me what I wanted’. I found them quite responsive to that. You are making a joke but they understand that the joke is actually serious. But you say it with a smile, and you say it softly.”

The desire for social harmony means Thais generally try to avoid conflict. Thailand is known as the land of smiles, what is less known is that Thais smile when they are happy, sad, irritated or angry. Asked a direct question they will try to choose the answer they think you are looking for. If, for example, a foreign colleague asked a Thai, “Do you want to have lunch tomorrow?” the answer is likely to be yes. Come tomorrow the Thai colleague may be nowhere to be found. In this scenario it is possible that they knew they could not make it but up until lunchtime you were happy! All is not lost however, it is better to ask indirectly, “maybe you would like to have lunch tomorrow?”. This gives them a chance to say, “maybe the day after is better?” In the classroom you should never say, “do you understand?” the answer will always be yes whether the content is understood or not. Instead the teacher should find other ways to determine if understanding of the content has taken place.

Another important Thai characteristic is summed up by the phrase ‘kreng jai’. There is no direct translation of it into English, it is something like not wanting to inconvenience or bother someone. In terms of online safety awareness and in particular mediation strategies this becomes an obstacle. In the interviews when students were asked what they did if they had a negative online experience invariably they would say that they did nothing and just kept silent. As one respondent replied (through an interpreter), “she said that she doesn’t tell anyone if it is not important.” Any online safety awareness initiative should take this into account especially on sensitive issues such as cyber-bullying.

4.3 Exploratory Workshops

With the cultural context in mind workshops were designed to test out different activities and teaching methods. As cyber-bullying was the main online safety issue it made sense to have this as the core topic. The workshops proved mostly successful [9] and were based on active learning methods like gamification. For example, one activity, the password challenge, used a password meter to show the strength, ranging from 0%–100%. Students were shown a method for creating strong passwords which they could then check on the meter [8].

While it cannot be called an education programme yet the theoretical, pedagogical and practical foundations have been laid for one to emerge. This and other aspects are discussed in the next section.

5 Conclusion and Future Work

The YPO Education Framework provides educators, researchers and policy makers a culturally relevant, evidence based construct for the effective teaching of online safety awareness. It is underpinned by sound research methodology and pedagogy with tried and tested activities that can be adapted to the needs of the target audience. The framework was applied to Thailand which resulted in a workshop series focusing on anti-cyberbullying [9]. Original research in the form of surveys and interviews were undertaken which sought to understand the attitude and behaviour of young people online and also the risks that could be potentially harmful.

Theories of culture were investigated and specifically how it affects teaching in Thailand. It found that Thai youth are use to the rote learning style, that what a teacher says is fact and not to be questioned. Teachers are held in high esteem but are also held responsible for the success or failure of a student. The workshops did find that students were receptive to active learning methods like gamification such as in the password challenge. The activities added to an applicability matrix which acts as a repository of tried and tested lessons. Notes on resources required and cultural context are included for the benefit of other educators and researchers. This practical aspect of the framework is in contrast to ones like the Kids Online model which focuses on data gathering and providing evidence for others.

Thus far the research has been conducted in the North East of Thailand. There is a plan to extend it to the south of the country in Songkhla province and possibly to other regions as well. By conducting further surveys, interviews and workshops it will build upon and extend the applicability of the framework. The goal will be to turn the workshops into a coherent and comprehensive education programme that can be a model for other LDCs.

References

Browell, S.: The land of smiles’: people issues in Thailand. Hum. Resource Dev. Int. 3(1), 109–119 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1080/136788600361975

Creswell, J.W.: Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research, 4th edn. Pearson, Boston (2012)

Deng, B.C.: The influence of individualism–collectivism on conflict management style: a cross- culture comparison between Taiwanese and US business employees. Master’s thesis, California State University, Sacramento (1992)

Eldridge, K., Cranston, N.: Managing transnational education: Does national culture really matter? J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 31(1), 67–79 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1080/13600800802559286

Gasser, U., Maclay, C.M., Palfrey Jr., J.G.: Working towards a deeper understanding of digital safety for children and young people in developing nations: an exploratory study by the Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University, in collaboration with UNICEF. Berkman Center Research Publication No. 2010-7; Harvard Public Law Working Paper No. 10-36 (2010). https://ssrn.com/abstract=1628276

Hall, E.T.: Beyond Culture. Doubleday, Garden City (1976)

Härkönen, U.: The Bronfenbrenner ecological systems theory of human development. Keynote presented at V International Conference Person.Color.Nature.Music, Daugavpils University, Saule. Latvia, 17–21 October 2017 (2007)

Herkanaidu, R., Furnell, S., Papadaki, M.: Using gamification in effective online safety awareness education. Presented at the 10th International Conference on Educational Research, ICER 2017, Faculty of Education, Khon Kaen University, Thailand, 9–10 September 2017 (2017)

Herkanaidu, R., Furnell, S., Papadaki, M., Khuchinda, T.: Designing an anti-cyberbullying programme in Thailand. In: Clarke, N.L., Furnell, S.M. (eds.) Proceedings of the Twelfth International Symposium on Human Aspects of Information Security & Assurance. Paper presented at HAISA 2018, Abertay University, Scotland, 29th–31st August. Plymouth, UK: Clarke Furnell (2018)

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G.J., Minkov, M.: Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, 3rd edn. McGraw-Hill, New York (2010)

Internet World Stats, 6 June 2018. Asia internet use, population data and Facebook statistics - June 2018. Internet World Stats website. http://www.internetworldstats.com/stats3.htm

Kainzbauer, A., Hunt, B.: Meeting the challenges of teaching in a different cultural environment – evidence from graduate management schools in Thailand. Asia Pacific J. Educ. 36(sup1), 56–68 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2014.934779

Knutson, T.J., Komolsevin, R., Chatiketu, P., Smith, V.R.: A cross-cultural comparison of Thai and US American rhetorical sensitivity: Implications for intercultural communication effectiveness. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 27, 63–78 (2003)

Livingstone, S., Byrne, J., Bulger, M.: Researching children’s rights globally in the digital age. Report of a seminar held on 12–14 February 2015. LSE, London (2015). http://www.lse.ac.uk/media@lse/research/Research-Projects/Researching-Childrens-Rights/pdf/Researching-childrens-rights-globally-in-the-digital-age-260515-withphotos.pdf

Livingstone, S., Mascheroni, G., Staksrud, E.: Developing a framework for researching children’s online risks and opportunities in Europe. LSE, London: EU Kids Online. (2015). http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/64470/

Park, J., Tan, M.: A policy review: Building digital citizenship in Asia-Pacific through safe, effective and responsible use of ICT. APEID-ICT in Education, UNESCO Asia-Pacific Regional Bureau of Education. (2016). http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0024/002468/246813E.pdf

Wilhelm, W.J., Gunawong, P.: Cultural dimensions and moral reasoning: a comparative study. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 36(5/6). (2016). https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSSP-05-2015-0047

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 IFIP International Federation for Information Processing

About this paper

Cite this paper

Herkanaidu, R., Furnell, S.M., Papadaki, M. (2020). Towards a Cross-Cultural Education Framework for Online Safety Awareness. In: Clarke, N., Furnell, S. (eds) Human Aspects of Information Security and Assurance. HAISA 2020. IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology, vol 593. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-57404-8_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-57404-8_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-57403-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-57404-8

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)