Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Editorial note

JOGI has been working hard to bring high quality science and research to our readers who are primarily involved in women’s health care, which is one of the top agendas of our country and also our vibrant organization, FOGSI. Women’s healthcare movement had begun way back in 1885. It took 65 years for likeminded professional to come together to establish FOGSI for the sole cause of women’s health and education. How far have we been successful in this mission? Will this unfinished agenda ever finish? What struggles women and doctors went through in yester years? I cannot think of a better person than the legendary Dr. Usha Saraiya who will have answers to all these queries coming to curious minds. She was honoured with Lady Reay medal as well as President of India medal as the best female medical student in 1959. She has witnessed the evolution of healthcare for women in her life time.

Dr. Usha Saraiya started her journey from Cama Hospital as a resident doctor and later continued as honorary consultant for about 35 years. As her students we had witnessed her passion and deep interest in historical aspects of Women’s health. She always paid tribute to her mentors Dr. Jerusha Jhirad, Dr. Aptekar and Dr. Winifred Fernandes, big names in field of obstetrics and gynecology of India in those days. They inspired her to work on the life sketches of pioneering women doctors. Eventually she published a book in 2006. It is often quoted and has become a reference book. Dr. Saraiya brought papsmear services to India in 1970 and helped introduce it in clinical practice. She has done pioneering work in the field of pap smear and colposcopy and her center in Cama hospital is now internationally accredited and has been training doctors from India and SAFOG countries for the last 45 years.

Dr. Saraiya has always been interested in research work and she has completed many projects with ICMR Grants. I was fortunate to work with her in one project “Tuberculosis in Pregnancy” [1]. I also feel proud to be associated with historic institutes like Grant medical college, Sir JJ hospital and Cama hospital, Mumbai, Chhatrapati Pramilatai Raje Hospital (CPR) Kolhapur and Association of Medical Women of India. I also feel extremely proud to be associated with this journal (JOGI) and FOGSI from where the women health care movement began.

In this editorial Dr. Saraiya shares her experience, and pearls from her treasury of history with our readers. It truly reflects her passion about history and its significance in present times. Enjoy the experience of looking back… looking forwards!

Professor Suvarna Khadilkar, Editor in chief.

Introduction

Today women’s health has become a significant platform for all to get on to. In addition to doctors, pharmaceutical industry, social organizations, women’s groups, philanthropists and government bodies have decided to contribute time, effort and money to this worthy cause.

There have been several slogans to promote health care for women like “Women’s Health–Nations Wealth” and “Healthy Mother–Healthy Family”. Many more such motivational messages have encouraged health professionals, especially the obstetricians and gynaecologists to participate in these programs. No doubt it has had an impact on our society and women’s health has been improving steadily over the years.

But to understand how and when this issue of women's health started being understood as a problem and soon became a challenge, we have to go back to the nineteenth century. That is why I call this “A story of the world of yesterday”.

Scenario in the Late Nineteenth Century

In the late nineteenth century, the health of women of India was in a sorry state. Life span was only 32 years as there was a high maternal and neonatal mortality. Diseases like anemia, tuberculosis and malnutrition were rampant. Social customs were such that women were not in a position to demand any healthcare.

However, many enlightened persons, social activists were deeply concerned. The country was governed by the British. Policies and budgets came from London. The British officialdom was also very sympathetic to the cause of Women’s Health. Queen Victoria (Fig. 1) was reigning and was designated as “Empress of India” in 1876. She was deeply interested in India [2].

It is said “She never visited India but, in many ways, India came to her”. Her trusted aide was Munshi Abdul Karim. He regaled her with many stories about India. Visiting dignitaries, Maharaja’s and Maharani’s called on her. She welcomed them to her court and listened to their problems. She even learnt Hindi at the age of 86 years so that she could communicate easily with her subjects from India. They informed her about the poor condition of women’s health. She promised to help and she actually did! She decided to send British women doctors to India. This was at a time when British women had just entered the medical profession against all odds and were struggling to establish themselves. Her sympathetic attitude changed the scenario.

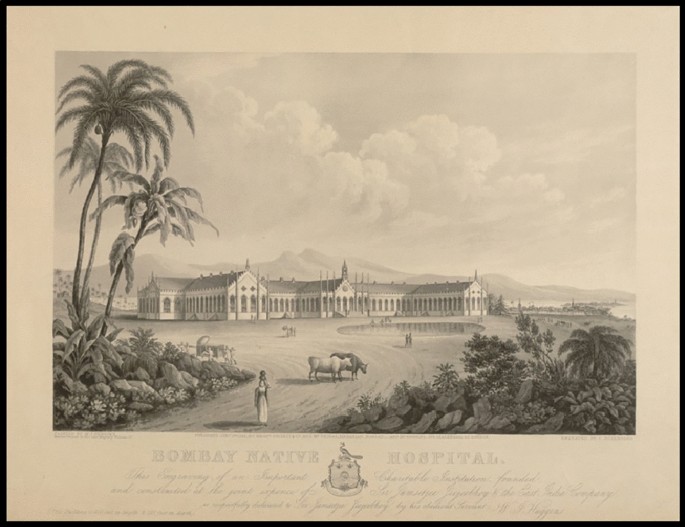

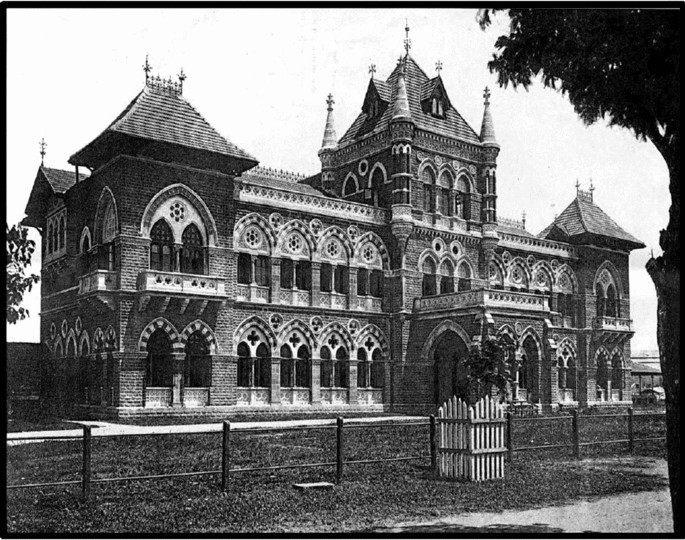

In the year 1845 the first medical college in India was started in Mumbai. The Grant Medical College (Fig. 2), which offered a licentiate course in modern medicine. Similar medical colleges were opened in Madras(Chennai) and Calcutta.

Mumbai was known as Bombay then! The population of Bombay realized the value of medical science. Doctors were treated as “God” and started practicing in areas around Bombay and gradually into remote villages in the country side. This college was not open to women, for the first 18 years of its existence. It was only in 1885 that the gates were opened to women. 5 brave women entered the profession. They were not welcomed but were actually ridiculed as they entered the classrooms. At about the same time, women were admitted in Calcutta and Madras colleges also.

The Pioneers

There were a handful of individuals who played a pivotal role and this epistle deals with the life and works of these contributors.

1 George Kittredge (1833-1917): He was an American American Businessman working in Bombay [3].

He was deeply concerned about the poor health status of women. He was a “compassionate capitalist” and believed that “great wealth involved social responsibility”. Capitalism and free enterprise had brought much prosperity to USA. Some compassionate capitalists felt duty bound to do social service nationally and internationally. Amongst them were Ford, Fullbright, Rockefeller and Kittredge in India.

His first objective was to begin a movement to collect funds for the worthy cause. It was called “Medical Women of India Fund of 1883” [4]. Contributions came from all over the world. This fund set up a scholarship fund for best woman graduate at MBBS examination of Bombay University. The student was also honoured with “Lady Reay Silver Medal” (Fig. 3) which was because of a donation from Lady Reay who was the wife of the Governor of Bombay. The student was also honoured with a silver medal from the President of India later in 1952 (Fig. 4). It was an incentive for women doctors to perform well and continue post graduate studies.

The 2nd objective of this fund was to bring well qualified British women doctors to India to set up and manage hospitals exclusively for women and children.

George Kittredge was in search of suitable lady doctors to bring to India. He met Dr. Edith Pechey in Paris in 1883 and she actually accepted his invitation.

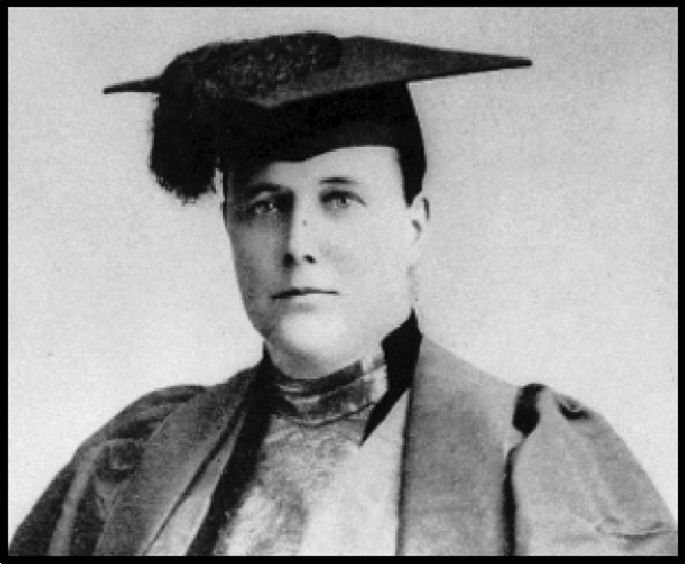

2 Dr. Edith Pechey Phipson (1845–1908) (Fig. 5).

Dr. Edith Pechey Phipson arrived in Mumbai in December 1885 and took charge as the 1st superintendent of Cama and Albless Hospital which opened in 1886 (Fig. 6) [5,6,7].

It was a hospital run by the women doctors for women and children of Bombay, started by parsi philanthropist.

She learnt hindi (local language) fast. She had progressive ideas about women’s social status and went about promoting women’s empowerment. She lent support to campaign against child marriage, promoted equal pay for equal work and encouraged the education of young girls and started nurses training.

She also got involved in other social and educational institutes as a member of Royal Asiatic Society of Bombay. She met and married Herbert Phipson in 1889. Incidentally he was also a member of Medical Women of India Fund. Unfortunately, she suffered ill health and developed diabetes. She gave 20 years of her life to improving the health care for women and children in Mumbai. During this time bubonic plague struck the city and her public health measures saved many lives.

Pechey Phipson and her husband returned to England in 1905. She continued her interest in improving the status of women. This time she championed the Suffragist movement. Her health let her down as she developed breast cancer and passed away in 1908.

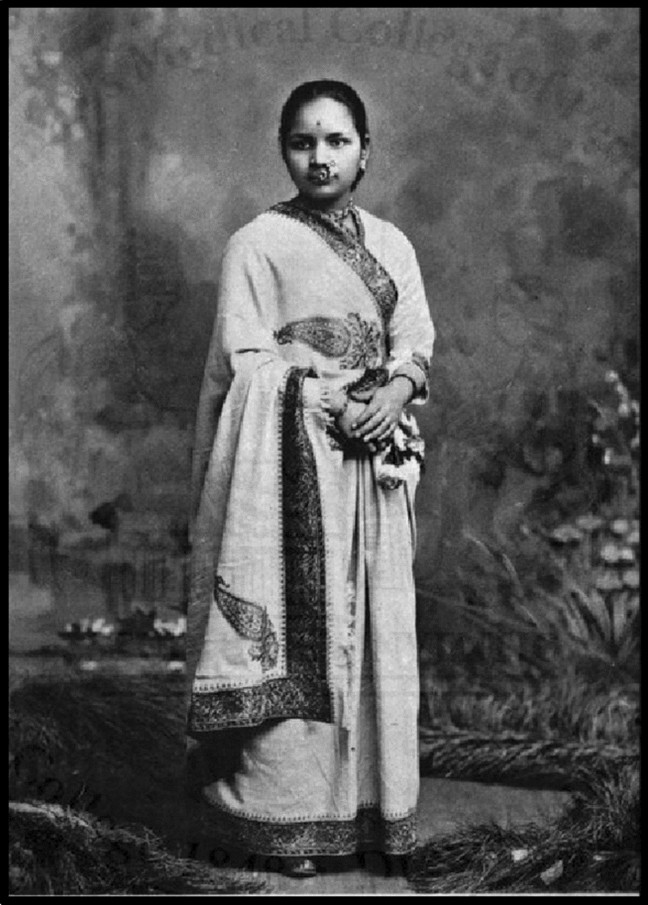

3 Dr. Anandibai Joshi(1865–1887): 1st indian woman doctor (Fig. 7).

A significant development at that time was the story of Anandibai Joshi who, against much opposition, went to USA and studied medicine. She was ostracised by the society for two unthinkable actions on her part. One was to get educated and that too in English language. And secondly to travel to a far-off country to learn medicine. She returned to India with a medical degree in 1886. Surprisingly on her return, the atmosphere had changed. She was welcomed with great jubilation. Telegrams and congratulations poured in. She was featured in Indian newspapers. Queen Victoria sent a personal congratulatory message to Anandibai and to the college which gave her the opportunity and scholarship. She was appointed “Physician in Charge” of the female ward of Albert Edward Hospital(today’s CPR hospital) in Kolhapur. This hospital is now affiliated to the medial college. Unfortunately, she fell ill with tuberculosis and succumbed to the disease at a tender young age of 22 years on February 26, 1887 [8].

4 Kadambini Ganguly: She was from kolkata and was one of the first two female physicians from India. She was also the first South Asian female physician, trained in western medicine, to graduate in South Asia in 1886. She fought for women’s rights [9].

5 Dr. Annette Benson: She was the next British medical doctor who succeeded Dr. Pechey Phipson as director and medical officer at the Cama and Albless Hospital. She was an able administrator and was deeply concerned about the working conditions of women doctors. With the idea of improving their condition, she formed the “Association of Medical Women in India” in 1907 and made it possible for women doctors to serve in the military hospitals during the 1st world war [10]. The services were much appreciated. The Dufferin Fund was set up in 1887 and opened several Dufferin hospitals all over India to give modern obstetric care to women [11].

The Lady Hardinge medical college for the medical education of women by women professors was started in Delhi.

In Bombay Cama and Albess hospital which was opened in 1886 with a heritage building continues to function today as a teaching hospital.

6 Jerusha Jhirad: (Fig. 8) She was Cama hospital's first Indian superintendent from 1928 to 1947 [12]. She did monumental research on the health status of women. She was invited by the government to conduct a statistical enquiry in Bombay on maternal deaths in Bombay from 1937–1938. She was also the chairman of the “Maternity and Child Welfare Advisory Committee” of ICMR.

She has been the founder member of FOGSI, its first president, and founder editor of the journal of FOGSI. She was well respected by the British government and was decorated with the title of "Member of British Empire" (MBE).

Her contributions were also appreciated by Government of India by conferring on her Padmashri in 1962.

On her 80th birthday, a library was opened in Cama Hospital called “Jhirad Library”. After her demise, her friends and well-wishers established an oration in her name which has become very prestigious with international and national orators.

In Bombay many maternity hospitals were set up by various communities for the welfare of women from their own communities. Some of these are Parsi lying-in hospital for parsi women, Ruxmani hospital for hindu women and Dholkawala maternity home for muslim women. Indian doctors were well qualified and could take care of all the cases.

7 Dr. Ida Scudder: She started a small medical dispensary and clinic for women in Vellore, near Madras (Chennai), with $10,000 grant from Mr. Schell, a Manhattan banker in 1899. She started the Mary Taber Schell Hospital in 1902, and later in 1918 opened a medical school for girls only, with financial backing from Reformed Church in America. This school is standing tall even today as Christian Medical College, Vellore [13].

But by the dawn of the twentieth century the tide had turned. Women doctors were looked up to and were given responsible jobs which saved many lives.

Thus, in the 50 years from 1885 to 1935 there was tremendous improvement in the healthcare of women. A cadre of efficient Indian men and women doctors were ready to take over all the hospitals set up for the purpose. They were ready to take up the challenges faced by the earlier generations. It must be mentioned that several prominent gentleman and powerful social organisations championed the cause of improving the status of women and making available modern health care. Thus, it became a social movement and had an impact of changing the attitude of people.

From 1935 to 1945, the world was torn asunder by the 2nd world war. India fought bravely with the British. At the same time India was fighting for “Swaraj” and to become an independent nation. All other social issues did not receive much attention. But the independence movement saw the rise of many competent women, freedom fighters, politicians and social workers. Women proved that, given a chance, they could contribute to the development of the nation.

Post-Independence India

Mahatma Gandhi wrote to Rajkumari Amrit Kaur on October 21st, 1936. “If you women would only realise your dignity and privilege and make full use of it for mankind, you would make the world a much better place than it is. Now I am in search of a woman who would realise her mission. Are you that woman or will you be one?

She must have been motivated by those words. A decade later in 1947, after independence, the 1st health minister was Rajkumari Amrit Kaur (Fig. 9).

She started attending to the problems of women’s health. India was one of the earliest nations to start “family planning” as a national programme in 1952. It gave a boost to the improvement of women’s health.

Organisational Support

With the establishment of FOGSI in the year 1950, there was a national organisation of professionals devoted to the cause of women’s health.

By then society had changed and become more modernised. The need for ‘Zenana Hospitals’ was no longer felt. Men and women doctors joined the organisations on equal footing. In recent times [14] the ratio of female doctors is increasing. In fact over the last 5 years, India has produced 4500 more female medical graduates than male ones [15]. There is no more paucity of women doctors caring for women.

Many brilliant obstetricians and gynaecologists from India and FOGSI made their mark nationally and internationally. Obstetrics benefited most by the development of blood transfusion, antibiotics, and anaesthesia which all came post world war II. This helped to bring down the maternal mortality rate.

International

Internationally United Nations and World Health Organisation came into existence to promote the cause of women’s health worldwide.

The millenuim development goals (MDG) announced in the year 2000 gave clear goals and directions. Many states in India did reach the goals and many others made substantial gains. After 2015 sustainable development goals (SDG) were announced with a time line of 2030. It has a broader outlay with emphasis on non-communicable diseases. One of its goals is to reduce mortality due to cancer by 30%. Hence prevention of cancer in women has become an important issue for women’s health.

Conclusion

We are now completing two decades of the twentyfirst century. Much has been achieved, but much more needs to be done. There are many social factors which are intrinsically linked to health. Women’s empowerment is perhaps the most important one. Empowerment through health and health through empowerment has also become a slogan. Social issues like girl’s education, safety and abolishment of child marriages are being emphasised and taken care of. However, poverty, malnutrition and housing are problems which are difficult to solve. Society needs to pay more attention to gender disparity and encourage gender harmony. It may take a few more generations perhaps to achieve, but we are on the right path and just need to keep walking.

One fine day, women’s health care may cease to be a special problem and it will just be a problem of “universal healthcare for humankind”.

References

Khadilkar SS, Saraiya U. Tuberculosis in pregnancy: a ten year overview. J Obst Gynecol Ind. 2003;53(5):453–7.

The History Press; India from Queen Victoria’s time to independence. https://www.thehistorypress.co.uk/articles/india-from-queen-victoria-s-time-to-independence.

Ahlekar RB. The Hindu—different tracks. 22/Feb/2016. https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/mumbai/different-tracks/article8266848.ece.

A sketch of the beginning and working the medical women of India fund. https://ia800608.us.archive.org/34/items/39002011128098.med.yale.edu/39002011128098.med.yale.edu.pdf.

Lutzker E. Edith Pechey-Phipson, MD: untold story. Med Hist. 1967;11(1):41–5. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0025727300011728.

Bradford E. The Thoresby society, The Historical Society for Leeds and District, March 2014. https://www.thoresby.org.uk/content/people/pechey.php.

Kumar A. Scroll.in.magzine, The pioneering female doctors of India whose contribution have been forgotten by history. 10/April/2017. https://scroll.in/magazine/831514/the-19th-century-women-doctors-of-india-whose-pioneering-work-has-been-forgotten-by-history.https://scroll.in/magazine/831514/the-19th-century-women-doctors-of-india-whose-pioneering-work-has-been-forgotten-by-history.

Saraiya UB. The firsts-life sketches of medical women in India. Published by Association of Medical Women in India to commemorate the century (1907–2007), January 2006.

Rao Amrith, Karim Omer, Motiwala H. 1071: the life and work of Dr Kadambini Ganguly, the first modern Indian woman physician. J Urol. 2007;177:354. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5347(18)31285-0.

Sehrawat S. Feminising Empire: the association of medical women in India and the campaign to found a women’s medical service. Soc Sci. 2013;41(5/6):65–81. www.jstor.org/stable/23611119. Accessed 17 Aug 2020.

The Dufferin fund. Ind Med Gaz. 1898;33(5):198.

Purandare CN, Patel MA, Balsarkar G. Indian contribution to obstetrics and gynecology. J Obstet Gynecol India. 2012;62:266–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13224-012-0270-5.

Graves D. Glimses, issue #113, Christian History Institute, retrieved 9/8/2007 Ida Scudder, a woman who changed her mind. 2005. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ida_S._Scudder.

Anand S, Fan V. The health workforce in India. 2016 WHO Library Catalouging-in publication data, ISBN 978 92 4 1510552 3FEM; chapter 2.3, p. 19.

Dar YA. The glaring case of indian medical ecosystem: more female medical graduates, but less female doctors, 6th Sept 2018. https://m.siliconindia.com/news/career/The-Glaring-Case-of-Indian-Medical-Ecosystem-More-Female-Medical-Graduates-but-Less-Female-Doctors-nid-205422.html#:~:text=Over%20the%20last%20five%20years,NEET%2D2018%20was%20a%20female.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges the support of Dr. Nidhi Shah Gandhi, Research Assistant and Ms. Maithilee Dighe, in the collection of historical data and the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Dr. Usha B. Saraiya [MD, DGO, FIAC, FICOG, FRCOG (UK)]. She is a consultant obstetrician and gynaecologist at Breach Candy Hospital, and Saifee Hospital Mumbai. India.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Saraiya, U.B. The Origin of Healthcare for Women in India: A Story of the World of Yesterday. J Obstet Gynecol India 70, 323–329 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13224-020-01371-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13224-020-01371-z