eBPF Documentation

eBPF is a revolutionary technology with origins in the Linux kernel that can run sandboxed programs in a privileged context such as the operating system kernel. It is used to safely and efficiently extend the capabilities of the kernel without requiring to change kernel source code or load kernel modules.

Historically, the operating system has always been an ideal place to implement observability, security, and networking functionality due to the kernel’s privileged ability to oversee and control the entire system. At the same time, an operating system kernel is hard to evolve due to its central role and high requirement towards stability and security. The rate of innovation at the operating system level has thus traditionally been lower compared to functionality implemented outside of the operating system.

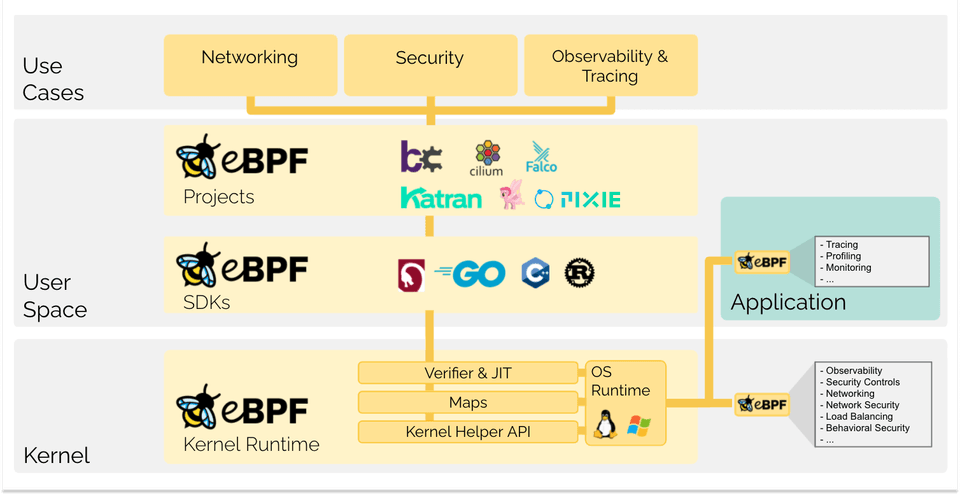

eBPF changes this formula fundamentally. It allows sandboxed programs to run within the operating system, which means that application developers can run eBPF programs to add additional capabilities to the operating system at runtime. The operating system then guarantees safety and execution efficiency as if natively compiled with the aid of a Just-In-Time (JIT) compiler and verification engine. This has led to a wave of eBPF-based projects covering a wide array of use cases, including next-generation networking, observability, and security functionality.

Today, eBPF is used extensively to drive a wide variety of use cases: Providing high-performance networking and load-balancing in modern data centers and cloud native environments, extracting fine-grained security observability data at low overhead, helping application developers trace applications, providing insights for performance troubleshooting, preventive application and container runtime security enforcement, and much more. The possibilities are endless, and the innovation that eBPF is unlocking has only just begun.

eBPF.io is a place for everybody to learn and collaborate on the topic of eBPF. eBPF is an open community and everybody can participate and share. Whether you want to read a first introduction to eBPF, find further reading material, or make your first steps to becoming contributors to major eBPF projects, eBPF.io will help you along the way.

BPF originally stood for Berkeley Packet Filter, but now that eBPF (extended BPF) can do so much more than packet filtering, the acronym no longer makes sense. eBPF is now considered a standalone term that doesn’t stand for anything. In the Linux source code, the term BPF persists, and in tooling and in documentation, the terms BPF and eBPF are generally used interchangeably. The original BPF is sometimes referred to as cBPF (classic BPF) to distinguish it from eBPF.

The bee is the official logo for eBPF and was originally created by Vadim Shchekoldin. At the first eBPF Summit there was a vote taken and the bee was named eBee. (For details on acceptable uses of the logo, please see the eBPF Foundation Brand Guidelines.)

The following chapters are a quick introduction into eBPF. If you would like to learn more about eBPF, see the eBPF & XDP Reference Guide. Whether you are a developer looking to build an eBPF program, or interested in leveraging a solution that uses eBPF, it is useful to understand the basic concepts and architecture.

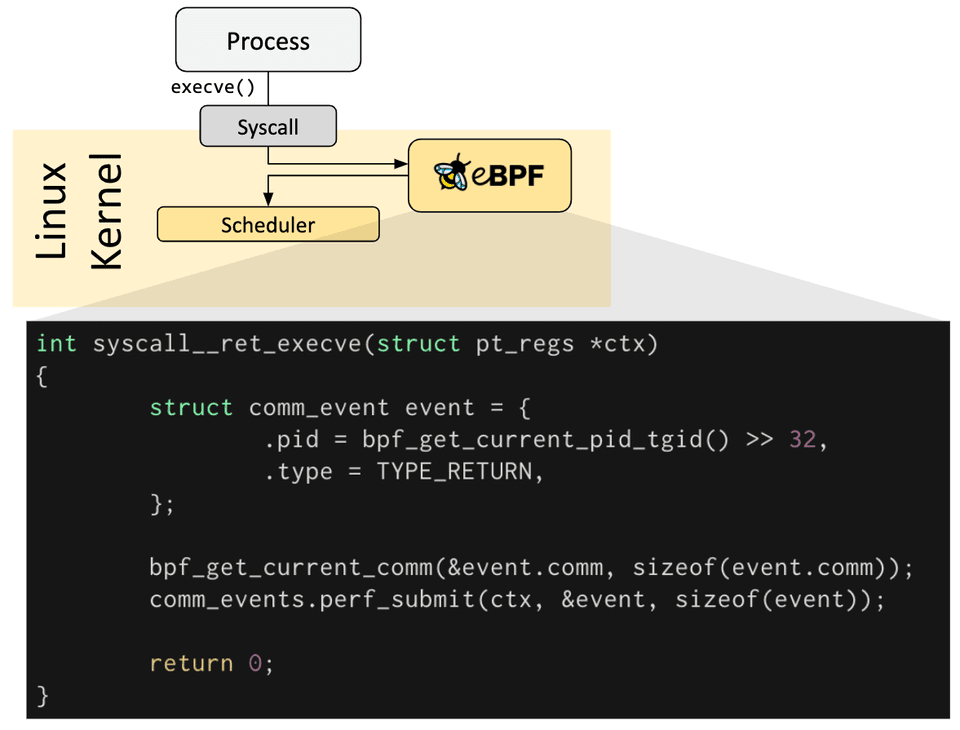

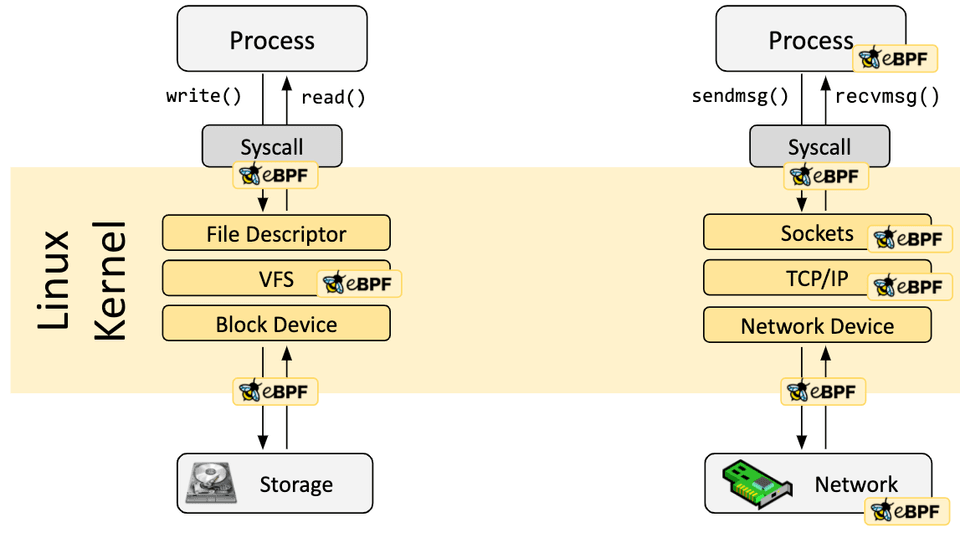

eBPF programs are event-driven and are run when the kernel or an application passes a certain hook point. Pre-defined hooks include system calls, function entry/exit, kernel tracepoints, network events, and several others.

If a predefined hook does not exist for a particular need, it is possible to create a kernel probe (kprobe) or user probe (uprobe) to attach eBPF programs almost anywhere in kernel or user applications.

In a lot of scenarios, eBPF is not used directly but indirectly via projects like Cilium, bcc, or bpftrace which provide an abstraction on top of eBPF and do not require writing programs directly but instead offer the ability to specify intent-based definitions which are then implemented with eBPF.

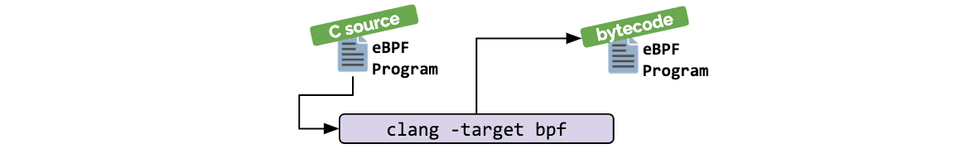

If no higher-level abstraction exists, programs need to be written directly. The Linux kernel expects eBPF programs to be loaded in the form of bytecode. While it is of course possible to write bytecode directly, the more common development practice is to leverage a compiler suite like LLVM to compile pseudo-C code into eBPF bytecode.

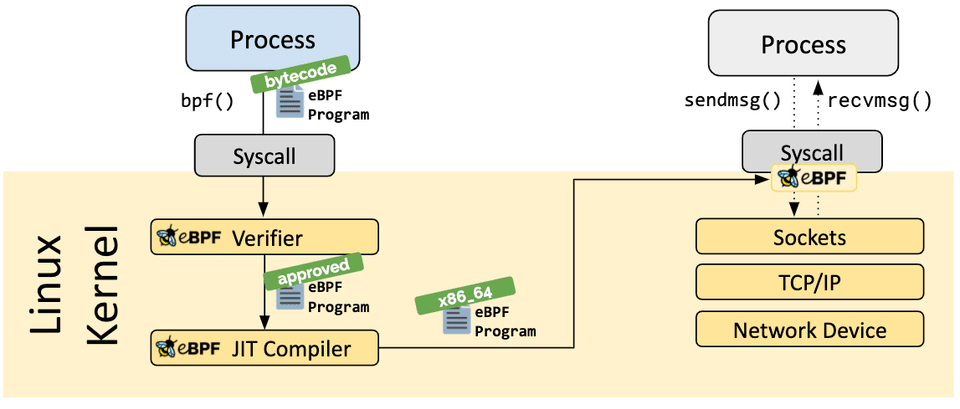

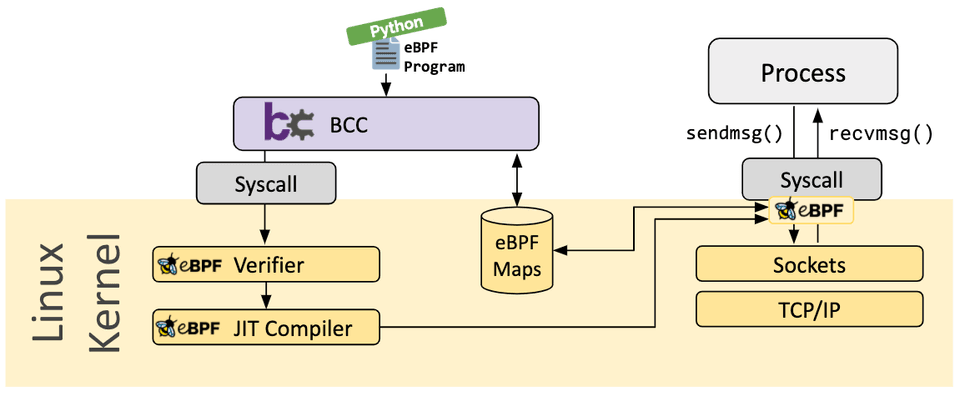

When the desired hook has been identified, the eBPF program can be loaded into the Linux kernel using the bpf system call. This is typically done using one of the available eBPF libraries. The next section provides an introduction into the available development toolchains.

As the program is loaded into the Linux kernel, it passes through two steps before being attached to the requested hook:

The verification step ensures that the eBPF program is safe to run. It validates that the program meets several conditions, for example:

- The process loading the eBPF program holds the required capabilities (privileges). Unless unprivileged eBPF is enabled, only privileged processes can load eBPF programs.

- The program does not crash or otherwise harm the system.

- The program always runs to completion (i.e. the program does not sit in a loop forever, holding up further processing).

The Just-in-Time (JIT) compilation step translates the generic bytecode of the program into the machine specific instruction set to optimize execution speed of the program. This makes eBPF programs run as efficiently as natively compiled kernel code or as code loaded as a kernel module.

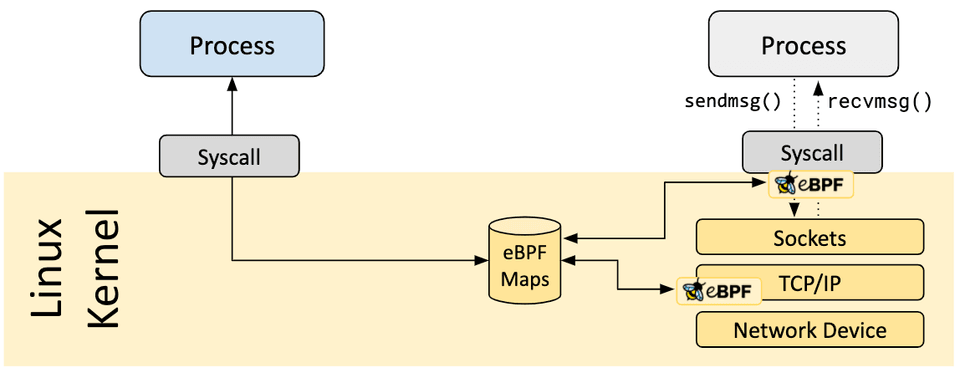

A vital aspect of eBPF programs is the ability to share collected information and to store state. For this purpose, eBPF programs can leverage the concept of eBPF maps to store and retrieve data in a wide set of data structures. eBPF maps can be accessed from eBPF programs as well as from applications in user space via a system call.

The following is an incomplete list of supported map types to give an understanding of the diversity in data structures. For various map types, both a shared and a per-CPU variation is available.

- Hash tables, Arrays

- LRU (Least Recently Used)

- Ring Buffer

- Stack Trace

- LPM (Longest Prefix match)

- ...

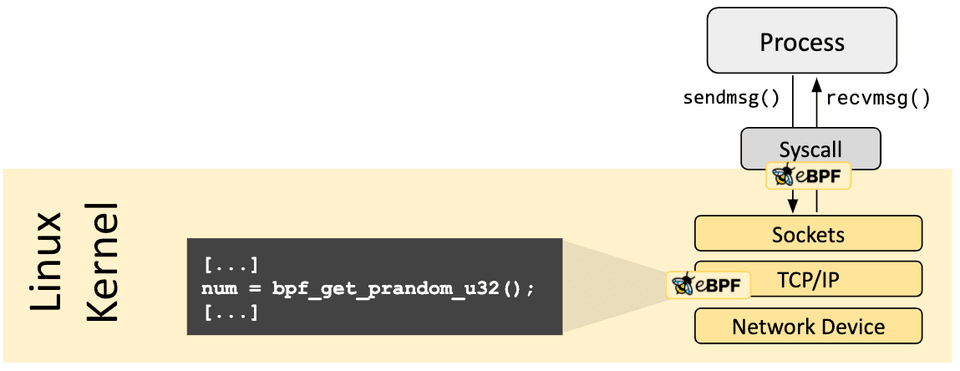

eBPF programs cannot call into arbitrary kernel functions. Allowing this would bind eBPF programs to particular kernel versions and would complicate compatibility of programs. Instead, eBPF programs can make function calls into helper functions, a well-known and stable API offered by the kernel.

The set of available helper calls is constantly evolving. Examples of available helper calls:

- Generate random numbers

- Get current time & date

- eBPF map access

- Get process/cgroup context

- Manipulate network packets and forwarding logic

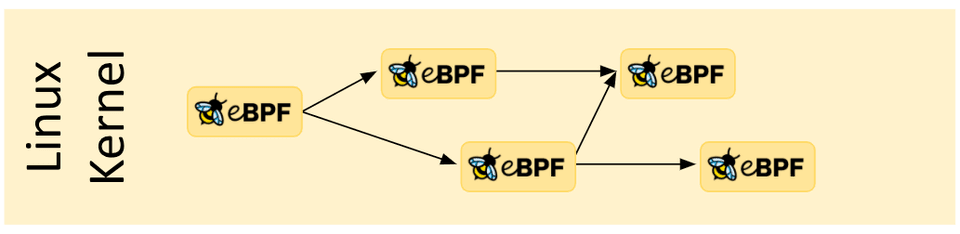

eBPF programs are composable with the concept of tail and function calls. Function calls allow defining and calling functions within an eBPF program. Tail calls can call and execute another eBPF program and replace the execution context, similar to how the execve() system call operates for regular processes.

With great power there must also come great responsibility.

eBPF is an incredibly powerful technology and now runs at the heart of many critical software infrastructure components. During the development of eBPF, the safety of eBPF was the most crucial aspect when eBPF was considered for inclusion into the Linux kernel. eBPF safety is ensured through several layers:

Required Privileges

Unless unprivileged eBPF is enabled, all processes that intend to load eBPF programs into the Linux kernel must be running in privileged mode (root) or require the capability CAP_BPF. This means that untrusted programs cannot load eBPF programs.

If unprivileged eBPF is enabled, unprivileged processes can load certain eBPF programs subject to a reduced functionality set and with limited access to the kernel.

Verifier

If a process is allowed to load an eBPF program, all programs still pass through the eBPF verifier. The eBPF verifier ensures the safety of the program itself. This means, for example:

- Programs are validated to ensure they always run to completion, e.g. an eBPF program may never block or sit in a loop forever. eBPF programs may contain so called bounded loops but the program is only accepted if the verifier can ensure that the loop contains an exit condition which is guaranteed to become true.

- Programs may not use any uninitialized variables or access memory out of bounds.

- Programs must fit within the size requirements of the system. It is not possible to load arbitrarily large eBPF programs.

- Program must have a finite complexity. The verifier will evaluate all possible execution paths and must be capable of completing the analysis within the limits of the configured upper complexity limit.

The verifier is meant as a safety tool, checking that programs are safe to run. It is not a security tool inspecting what the programs are doing.

Hardening

Upon successful completion of verification, the eBPF program runs through a hardening process according to whether the program is loaded from a privileged or unprivileged process. This step includes:

- Program execution protection: The kernel memory holding an eBPF program is protected and made read-only. If for any reason, whether it is a kernel bug or malicious manipulation, the eBPF program is attempted to be modified, the kernel will crash instead of allowing it to continue executing the corrupted/manipulated program.

- Mitigation against Spectre: Under speculation CPUs may mispredict branches and leave observable side effects that could be extracted through a side channel. To name a few examples: eBPF programs mask memory access in order to redirect access under transient instructions to controlled areas, the verifier also follows program paths accessible only under speculative execution and the JIT compiler emits Retpolines in case tail calls cannot be converted to direct calls.

- Constant blinding: All constants in the code are blinded to prevent JIT spraying attacks. This prevents attackers from injecting executable code as constants which in the presence of another kernel bug, could allow an attacker to jump into the memory section of the eBPF program to execute code.

Abstracted Runtime Context

eBPF programs cannot access arbitrary kernel memory directly. Data and data structures that lie outside of the context of the program must be accessed via eBPF helpers. This guarantees consistent data access and makes any such access subject to the privileges of the eBPF program, e.g. only data structures relevant to the program's type can be read or (sometimes) modified, provided the verifier could ensure at load time that out-of-bound accesses will never happen; or an eBPF program running is only allowed to modify the data of certain data structures if the modification can be guaranteed to be safe. An eBPF program cannot randomly modify data structures in the kernel.

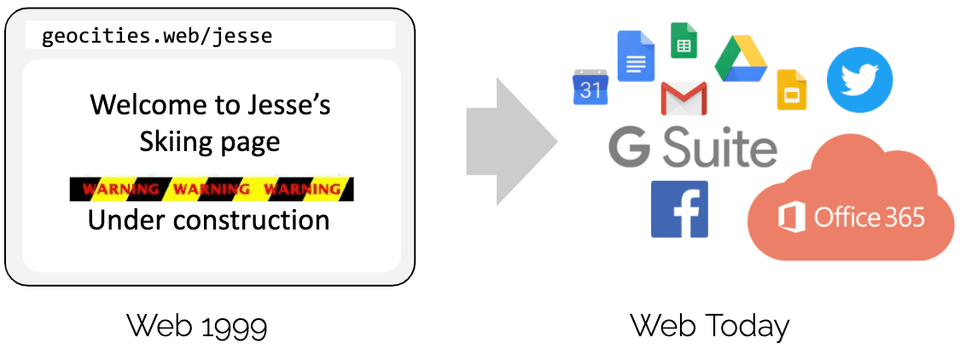

Let’s start with an analogy. Do you remember GeoCities? 20 years ago, web pages used to be almost exclusively written in static markup language (HTML). A web page was basically a document with an application (browser) able to display it. Looking at web pages today, web pages have become full-blown applications and web-based technology has replaced a vast majority of applications written in languages requiring compilation. What enabled this evolution?

The short-answer is programmability with the introduction of JavaScript. It unlocked a massive revolution resulting in browsers evolving into almost independent operating systems.

Why did the evolution happen? Programmers were no longer as bound to users running particular browser versions. Instead of convincing standards bodies that a new HTML tag was needed, the availability of the necessary building blocks decoupled the pace of innovation of the underlying browser from the application running on top. This is of course a bit oversimplified as HTML did evolve over time and contributed to the success but the evolution of HTML itself would not have been sufficient.

Before taking this example and applying it to eBPF, let's look at a couple of key aspects that were vital in the introduction of JavaScript:

- Safety: Untrusted code runs in the browser of the user. This was solved by sandboxing JavaScript programs and abstracting access to browser data.

- Continuous Delivery: Evolution of program logic must be possible without requiring to constantly ship new browser versions. This was solved by providing the right low-level building blocks sufficient to build arbitrary logic.

- Performance: Programmability must be provided with minimal overhead. This was solved with the introduction of a Just-in-Time (JIT) compiler. For all of the above, exact counterparts can be found in eBPF for the same reason.

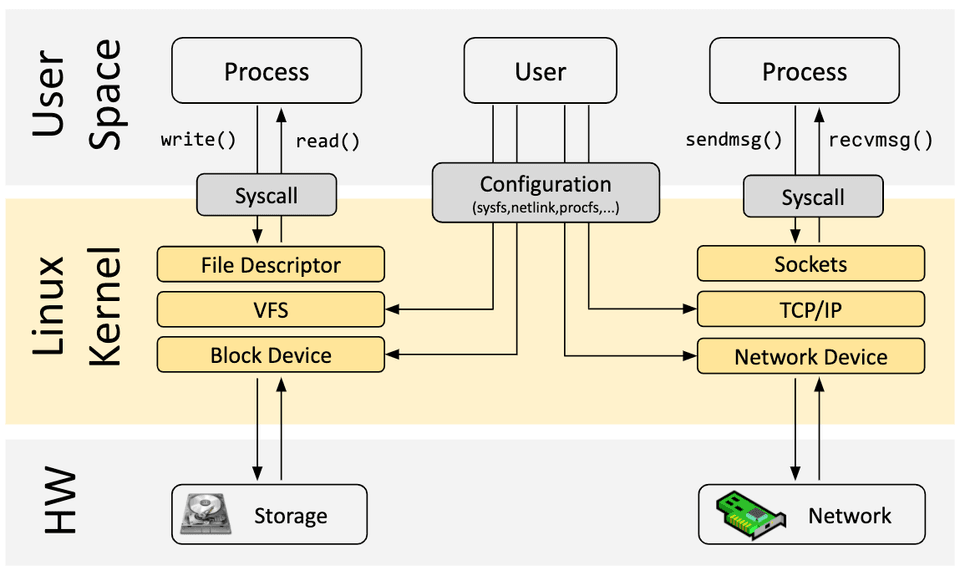

Now let’s return to eBPF. In order to understand the programmability impact of eBPF on the Linux kernel, it helps to have a high-level understanding of the architecture of the Linux kernel and how it interacts with applications and the hardware.

The main purpose of the Linux kernel is to abstract the hardware or virtual hardware and provide a consistent API (system calls) allowing for applications to run and share the resources. In order to achieve this, a wide set of subsystems and layers are maintained to distribute these responsibilities. Each subsystem typically allows for some level of configuration to account for different needs of users. If a desired behavior cannot be configured, a kernel change is required, historically, leaving two options:

Native Support

- Change kernel source code and convince the Linux kernel community that the change is required.

- Wait several years for the new kernel version to become a commodity.

Kernel Module

- Write a kernel module

- Fix it up regularly, as every kernel release may break it

- Risk corrupting your Linux kernel due to lack of security boundaries

With eBPF, a new option is available that allows for reprogramming the behavior of the Linux kernel without requiring changes to kernel source code or loading a kernel module. In many ways, this is very similar to how JavaScript and other scripting languages unlocked the evolution of systems which had become difficult or expensive to change.

Several development toolchains exist to assist in the development and management of eBPF programs. All of them address different needs of users:

bcc

BCC is a framework that enables users to write python programs with eBPF programs embedded inside them. The framework is primarily targeted for use cases which involve application and system profiling/tracing where an eBPF program is used to collect statistics or generate events and a counterpart in user space collects the data and displays it in a human readable form. Running the python program will generate the eBPF bytecode and load it into the kernel.

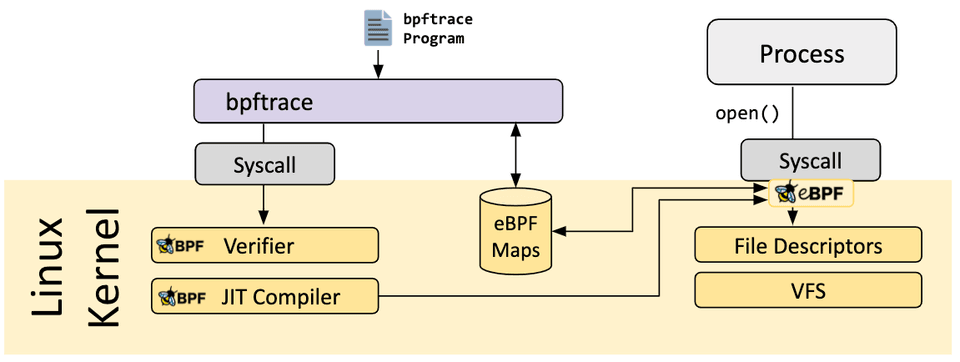

bpftrace

bpftrace is a high-level tracing language for Linux eBPF and available in semi-recent Linux kernels (4.x). bpftrace uses LLVM as a backend to compile scripts to eBPF bytecode and makes use of BCC for interacting with the Linux eBPF subsystem as well as existing Linux tracing capabilities: kernel dynamic tracing (kprobes), user-level dynamic tracing (uprobes), and tracepoints. The bpftrace language is inspired by awk, C, and predecessor tracers such as DTrace and SystemTap.

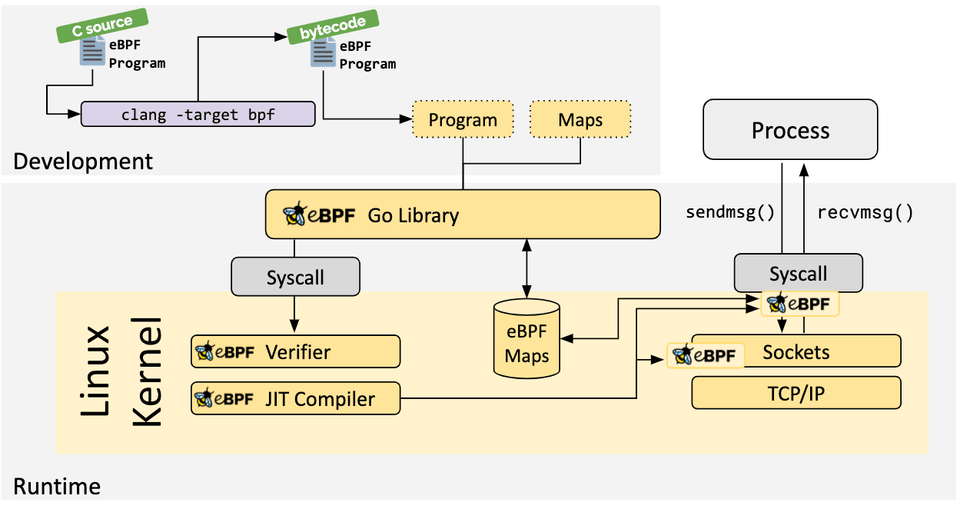

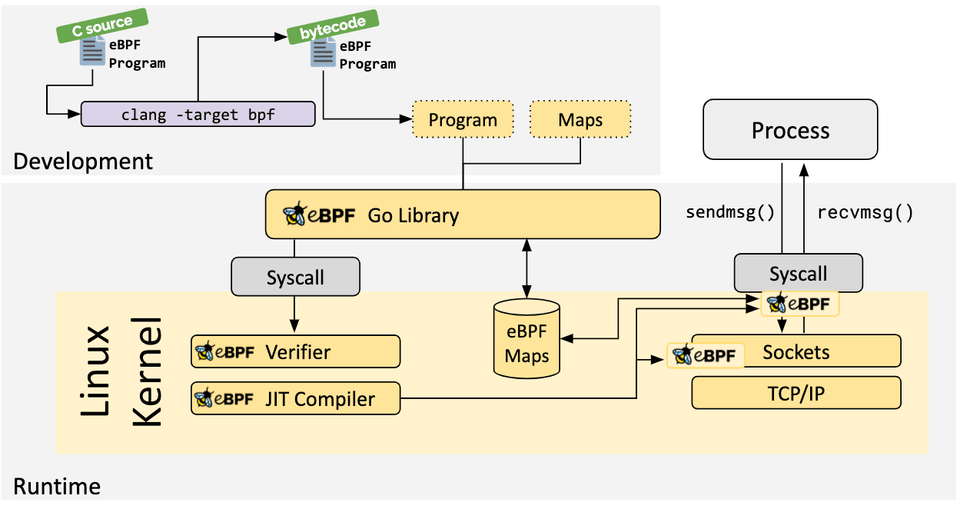

eBPF Go Library

The eBPF Go library provides a generic eBPF library that decouples the process of getting to the eBPF bytecode and the loading and management of eBPF programs. eBPF programs are typically created by writing a higher level language and then use the clang/LLVM compiler to compile to eBPF bytecode.

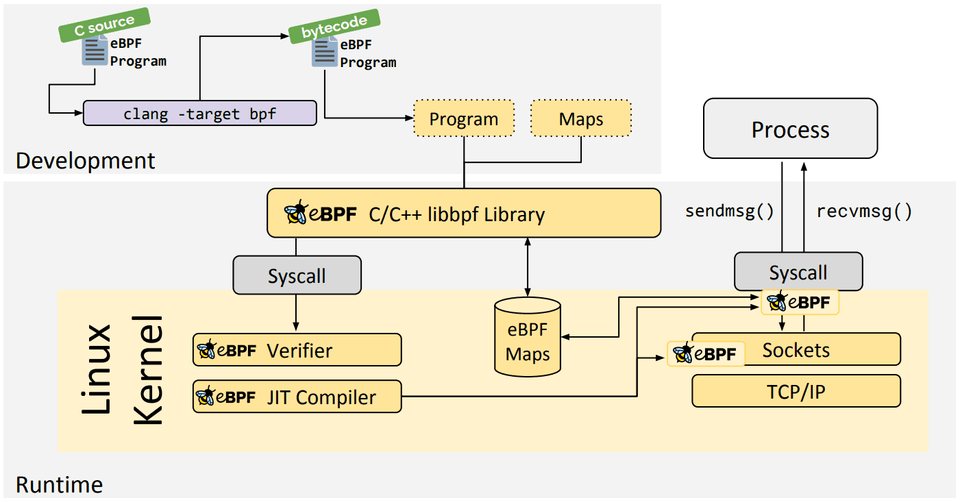

libbpf C/C++ Library

The libbpf library is a C/C++-based generic eBPF library which helps the loading of eBPF object files generated from the clang/LLVM compiler into the kernel and generally abstracts interaction with the BPF system call by providing easy to use library APIs for applications.

If you would like to learn more about eBPF, continue reading using the following additional materials:

- BPF & XDP Reference Guide, Cilium Documentation, Aug 2020

- BPF Documentation, BPF Documentation in the Linux Kernel

- BPF Design Q&A, FAQ for kernel-related eBPF questions

- Learn eBPF Tracing: Tutorial and Examples, Brendan Gregg's Blog, Jan 2019

- XDP Hands-On Tutorials, Various authors, 2019

- BCC, libbpf and BPF CO-RE Tutorials, Facebook's BPF Blog, 2020

- eBPF Tutorial: Learning eBPF Step by Step with Examples, Various authors, 2024

Generic

- eBPF and Kubernetes: Little Helper Minions for Scaling Microservices (Slides), Daniel Borkmann, KubeCon EU, Aug 2020

- eBPF - Rethinking the Linux Kernel (Slides), Thomas Graf, QCon London, April 2020

- BPF as a revolutionary technology for the container landscape (Slides), Daniel Borkmann, FOSDEM, Feb 2020

- BPF at Facebook, Alexei Starovoitov, Performance Summit, Dec 2019

- BPF: A New Type of Software (Slides), Brendan Gregg, Ubuntu Masters, Oct 2019

- The ubiquity but also the necessity of eBPF as a technology, David S. Miller, Kernel Recipes, Oct 2019

Deep Dives

- BPF and Spectre: Mitigating transient execution attacks (Slides) , Daniel Borkmann, eBPF Summit, Aug 2021

- BPF Internals (Slides), Brendan Gregg, USENIX LISA, Jun 2021

Cilium

- Advanced BPF Kernel Features for the Container Age (Slides), Daniel Borkmann, FOSDEM, Feb 2021

- Kubernetes Service Load-Balancing at Scale with BPF & XDP (Slides), Daniel Borkmann & Martynas Pumputis, Linux Plumbers, Aug 2020

- Liberating Kubernetes from kube-proxy and iptables (Slides), Martynas Pumputis, KubeCon US 2019

- Understanding and Troubleshooting the eBPF Datapath in Cilium (Slides), Nathan Sweet, KubeCon US 2019

- Transparent Chaos Testing with Envoy, Cilium and BPF (Slides), Thomas Graf, KubeCon EU 2019

- Cilium - Bringing the BPF Revolution to Kubernetes Networking and Security (Slides), Thomas Graf, All Systems Go!, Berlin, Sep 2018

- How to Make Linux Microservice-Aware with eBPF (Slides), Thomas Graf, QCon San Francisco, 2018

- Accelerating Envoy with the Linux Kernel, Thomas Graf, KubeCon EU 2018

- Cilium - Network and Application Security with BPF and XDP (Slides), Thomas Graf, DockerCon Austin, Apr 2017

Hubble

- Hubble - eBPF Based Observability for Kubernetes, Sebastian Wicki, KubeCon EU, Aug 2020

- Learning eBPF, Liz Rice, O'Reilly, 2023

- Security Observability with eBPF, Natália Réka Ivánkó and Jed Salazar, O'Reilly, 2022

- What is eBPF?, Liz Rice, O'Reilly, 2022

- Systems Performance: Enterprise and the Cloud, 2nd Edition, Brendan Gregg, Addison-Wesley Professional Computing Series, 2020

- BPF Performance Tools, Brendan Gregg, Addison-Wesley Professional Computing Series, Dec 2019

- Linux Observability with BPF, David Calavera, Lorenzo Fontana, O'Reilly, Nov 2019

- BPF for security - and chaos - in Kubernetes, Sean Kerner, LWN, Jun 2019

- Linux Technology for the New Year: eBPF, Joab Jackson, Dec 2018

- A thorough introduction to eBPF, Matt Fleming, LWN, Dec 2017

- Cilium, BPF and XDP, Google Open Source Blog, Nov 2016

- Archive of various articles on BPF, LWN, since Apr 2011

- Various articles on BPF by Cloudflare, Cloudflare, since March 2018

- Various articles on BPF by Facebook, Facebook, since August 2018