Jahanpanah was the fourth medieval city of Delhi established in 1326–1327 by Muhammad bin Tughlaq (reigned 1325–51) of the Delhi Sultanate. To counter the persistent threat of Mongol invasions, Tughlaq constructed the fortified city of Jahanpanah (meaning "Refuge of the World" in Persian), incorporating the Adilabad Fort, built in the 14th century, along with all the establishments located between Qila Rai Pithora and Siri Fort. Neither the city nor the fort has survived. Many reasons have been offered for such a situation. One of these is exemplified by the idiosyncratic rule of Mohammed bin Tughlaq, who inexplicably decreed the capital to be moved to Daulatabad in the Deccan, only to return to Delhi soon after.[1][2][3]

| Jahanpanah | |

|---|---|

Jahanpanah | |

Bijaymandal in Jahanpanah, the fourth city of Medieval Delhi | |

| General information | |

| Type | Forts, Mosques and Tombs |

| Architectural style | Tughlaq |

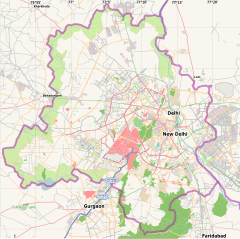

| Location | South Delhi |

| Country | India |

| Coordinates | 28°31′16″N 77°14′46″E / 28.521°N 77.246°E |

| Construction started | 1326 A.D. |

| Completed | 1327 A.D. |

| Client | Tughlaq Dynasty |

| Owner | Government of Delhi |

| Technical details | |

| Floor area | Fort area: 20 ha (49.4 acres) |

| References | |

| [1] | |

The ruins of the city's walls are even now discerned in the road between Siri to Qutub Minar, and also in isolated patches behind the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), in Begumpur, Khirki Masjid, Satpula and many other nearby locations; at some sections, as seen at Satpula, the fort walls were large enough to have few inbuilt storerooms to stack provisions and armory. The mystery of the city's precincts (complex) has unfolded over the years with later day excavations revealing a large number of monuments in the villages and residential colonies of South Delhi.

Due to the constraints triggered by the unfettered urban expansion of the capital city of Delhi, Jahanpanah is now engulfed by the upscale urban developments of South Delhi. The village and the wealth of ruins scattered all around are now enclosed by the South Delhi suburbs of Panchsheel Park, Malviya Nagar, Adchini, and the Aurobindo Ashram. It is hemmed in the North–South direction between the Outer Ring Road and the Qutb Complex and on the east–west direction by the Mehrauli road and the Chirag Delhi road, with Indian Institute of Technology located on the other side of the Mehrauli road as an important landmark.[4][5][6]

Etymology

editJahanpanah's etymology consists of two Persian words, جهان ‘Jahan’, "the world", and پناه ‘panah’,"shelter", thus "Refuge of the World"

History

editMohammed bin Tughlaq, the son of Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq who ordered the establishment of Tughlaqabad, constructed the new city of Jahanpanah between 1326 and 1327 by encircling and hemming the earlier cities of Siri and Lal Kot with 13 gates.[7] But what remains of the city and Adilabad fort are largely ruins, which leave much ambiguity and conjecture regarding its physical status as to why and when it was built by Tughlaq. Some of the structures which have survived partially are the Bijay Mandal (that is inferred to have housed the Hazar Sutan Palace, now destroyed), Begumpur Mosque, Serai Shaji Mahal, Lal Gumbad, Baradari with other nearby structures and scattered swathes of rubble masonry walls. From Ibn Batuta’s chronicle of the period (he lived in Delhi from 1333–41), it is inferred that Lal Kot (Qutb complex) then constituted the urban area, Siri was the military cantonment, and the remaining area consisted of his palace (Bijaymandal) and other structures like mosques, etc.[5][8]

Ibn Batuta reasoned that Muhammad Shah wished to see a unified city comprising Lal Kot, Siri, Jahanpanah and Tughlaqabad with one contiguous fortification encompassing them but cost considerations compelled him to abandon the plan halfway. In his chronicle, Batuta also stated that the Hazar Sutan Palace (palace of a thousand pillars), built outside the Siri fort limits but within the Jahanpanah City area, was the residence of the Tughlaqs.[5][9]

Hazar Sutan Palace was located within the fortified area of the Jahnapanah in Bijaya Mandal (literal meaning in Hindi: 'victory platform'). The grand palace with its audience hall of the beautifully painted wooden canopy and columns is vividly described but it does no longer exists. The Fort acted as a safe haven for the people living between Qila Rai Pithora and Siri. Tughalqabad continued to act as Tughlaq’s centre of government until, for strange and inexplicable reasons, he shifted his capital to Daulatabad, however, he returned after a short period.[4]

Adilabad

editAdilabad, a fort of modest size, built on the hills to the south of Tughlaqabad, was provided with protective massive ramparts on its boundary around the city of Jahanpanah. The fort was much smaller than its predecessor fort, Tughlaqabad fort, but of similar design. Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) in its evaluation of the status of the fort for conservation has recorded that two gates,

one with barbicans between two bastions on the south-east and another on the south-west. Inside, it, separated by a bailey, is a citadel consisting of walls, bastions and gates within which lay the palaces.[3][10]

The fort was also known as ‘Muhammadabad’, but inferred as a latter-day development.[4] The two gates on the southeast and southwest of Adilabad fort had chambers at the lower level while the east and west gates had grain bins and courtyards at the upper floors. The fortifications built, linking with the other two city walls, was 12 m (39.4 ft) in thickness and extended to a length of 8 km (5.0 mi). Another smaller fortress, called the Nai-ka-Kot (literally "Barber's fortress") was also built at a distance of about 700 m (2,296.6 ft) from Adilabad, with the citadel and army camps, which are now seen only in ruins.[11]

Tughlaq's primary attention to infrastructure, particularly of iron supply to the city, was also well thought-out. A structure (weir or tank) with seven sluices (Hindi: Satpula, meaning "seven bridges") was built on a stream that flowed through the city. This structure called the Satpula still exists (though non–functional), located near Khirki village on the boundary walls of Jahanpanah. Similar structures had also been built at Tughlaqabad and Delhi in Hauz Khas Complex, thus covering the water supply needs of entire population of Jahanpanah.[12]

Khirki Mosque lies in Khirki village.

Begampur Mosque

editToday, remnants of the city lie scattered across Begumpur village, serving as a silent testament to its ancient glory. The Begumpur Mosque, a vestige of the old city, of overall layout plan of 90 m × 94 m (295.3 ft × 308.4 ft) with the inner courtyard measuring 75 m × 80 m (246.1 ft × 262.5 ft), is said to be patterned on an Iranian design coonceived by an Iranian architect called Zahir al-Din al-Jayush. A majestic building in the heart of the city with pride of place played a pivotal role in serving as a madrasa, an administrative centre with the treasury and a mosque of large proportions serving as a social community hub surrounded by a market area. It has an unusual layout with three arches covered passages with a "three by eight" deep nine-bay prayer hall on the west. The construction of this mosque is credited to two sources. One view is that it was built by Khan-i-Jahan Maqbul Tilangani, prime minister during Feroz Shah Tughlaq’s rule, who was also a builder of six more masjids (two of them in the close vicinity). The other view is that it was built by Tughlaq because of its proximity to Bijay Mandal and could probably be dated to 1351 A.D., the year Tughlaq died here. In support of the second view, it is said that Ibn Batuta, the chronicler of the period (till his departure from Delhi in 1341 A.D.) had not recorded this monument. The mosque, considered an architectural masterpiece, has three gates, one in each of the three covered passages: in the north, east (main gate) and south. The west wall which has the mihrab, has Tughluqi-style tapering minarets flanking the central high opening covered by a big dome. The entire passageway of the west wall has twenty-five arched openings. The mihrab wall depicts five projections.

The prayer hall has modest decorative carvings but the columns and walls are bland. The eastern gate approach is from the road level up a flight of steps to negotiate the raised plinth on which this unique mosque has been built with a four-iwan layout. Stone chajjas or eaves can also be seen on all the four arcades. The northern entry with 1 m (3.3 ft) raised entrance, probably linked the mosque to the Bijayamandal Palace. The stucco plastering work on the mosque walls has lasted for centuries and even now shows some tiles fixed on them at a few locations. The mosque was under occupation during Jahanpanah's existence till the 17th century. In the modern era, encroachers took over the mosque but were eventually evicted by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) in 1921. A shuttered by-lane entry from the north has been interpreted as an approach that was used by the womenfolk of the Sultan's family for attending prayers in the mosque.[4][5][6][11]

Bijay Mandal

editBijay Mandal is a structure with a layout measuring 74 m (242.8 ft) by 82 m (269.0 ft), featuring a well-proportioned square dome. It cannot be categorized as a tower or a palace though.[5][13] It is a Tughlaqi structure with an octagonal plan built in rubble masonry (with massive battered sloping walls on east, west and southern directions) on a raised platform with doorways in each cardinal direction. The purpose of this unusual structure and the ruins of the Sar Dara Palace was described by Ibn Battuta as the palace with multiple chambers and the large public audience hall as the famed Hazar Sutan Palace. It was also interpreted as serving as an observation tower to monitor the activities of his troops. The ambiance of the place presented it as a place to relax and enjoy the scenic view of the environs. The inclined path around the monument was a walkway leading to the apartments of the Sultan. Two large openings in the living rooms of the floor were inferred as leading to the vaults or the treasury. On the level platform, outside the building in front of the apartment rooms, small holes equally spaced are seen, which have been inferred to be holes used to fix wooden pillars to hold a temporary shamiana (pavilion) or cover.

The process of ushering people into the presence of the Sultan was labyrinthine and formal, involving entry through semi–public places to private chambers to the audience hall. The debate over whether the Hazara Sultan Palace mentioned as existing during Alauddin Khalji's reign was the same structure present during the Tughlaq period remains inconclusive. A plausible hypothesis is that the stone hall of the palace was built by Alauddin Khalji while the tower adjoining the stone buildings was surely built by Mohammed bin Tughlaq.[3][4][5][12][13]

Archaeological excavations carried out by the Archaeological Survey of India unearthed treasures from the vaults in the buildings, which date the occupation of this monument during Feroz Shah's reign and also by Sheikh Hasan Tahir (a saint) during Sikander Lodi’s rule at the beginning of the 16th century. Furthermore, excavations conducted in 1934 have revealed wooden pillar bases attributed to the Hazar Sutan Palace.[4][5][13] Within the close precincts of Bijay Mandal stands a conspicuous domed building, distinguished by a unique architectural façade featuring two openings on each of its three sides. This structure is thought to be an annex to another building, as indicated by underground passages connecting it to an adjoining structure. However, the purpose for which this dome was originally built remains unknown.[5]

- Kalusarai Masjid

Kalu Sarai Masjid, situated 500 m (1,640.4 ft) north of Bijay Mandal, is in a severely dilapidated condition and urgently requires restoration due to its status as a heritage monument. Currently, it is illegally occupied as a residential complex.

The Masjid was built by the eminent mosque builder Khan-i-Jahan Maqbul Tilangani, who served as Prime Minister during the reign of Feroz Shah Tughlaq, as one of the seven mosques he constructed; this particular mosque retains the same architectural panache as the other six commissioned by him. Even today, the visible decorations of the mihrab appear more intricate than those in his other mosques. Originally constructed with rubble masonry and plastered surfaces, the mosque featured a frontage of seven arched openings, three bays in depth, and was crowned by a series of low domes, exemplifying the typical Tughlaqi architectural style.[4][5][14]

Serai Shaji Mahal

editEast of Begumpur Masjid, in the village of Serai Shahji, lie edifices from the Mughal period, among which the Serai Shahji Mahal stands as a notable monument. The area surrounding this structure is scattered with decrepit gates, graves, and irregular urban tenements. A bit further from this structure is the tomb of Shaikh Farid Murtaza Khan, who during Emperor Akbar’s period, was credited with building a number of serais, a mosque, and Faridabad village, which is now the present–day large city in Haryana.[4][5]

Other notable structures

editOther notable structures in the Jahanpanah's ambit of 20 ha (49.4 acres) area in close vicinity of the present day Panchshila Public School are the following:[1][4][5]

The Lal Gumbad was built as a tomb for Shaikh Kabbiruddin Auliya (1397), a 14th century Sufi saint who served as a disciple of Sufi saint Shaikh Raushan Chiragh–i–Delhi. The dome tomb was built with red sandstone. It is considered to be a small size replica of the Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq’s Tomb in Tughlaqabad.[15] The gateway to the tomb has a pointed arch with marble bands. It is also called the Rakabwala Gumbad as dacoits stolen the finial on the roof of the tomb by climbing up over the iron rungs (called 'Rakab') on its western wall. Apart from these structures, the four walls of a mosque also are located within the compound of the tomb.

The vicinity of Sadhana Enclave features the Baradari, an arched hall. Thought to have been built in the 14th century or 15th century, it is in a fairly well-preserved condition.[16] A Lodi period tomb is also seen nearby.

Farther from Sadhana Enclave, on its opposite side in Sheikh Serai, three tombs are noted, of which only one is well preserved: the square-domed tomb of Sheikh Alauddin (1541–42).[17] The tomb building, elevated on twelve columns with perforated screens on the façade, features a large dome set on a sixteen-faced drum. The ceiling is adorned with intricate plaster medallions on the spandrels of the arches, while the parapets display a merlon design.

Conservation measures

editArchaeological excavations were done by ASI in part of the fort walls at its junction with the eastern wall of Qila Rai Pithora. The excavations revealed rough and small stones in the foundations followed by an ashlar face in the exterior wall above ground. The ASI undertook conservation efforts for the wall, including the installation of railings, environmental improvements, and enhanced lighting, at a cost of ₹15 lakhs (US$30,000) in preparation for the 2010 Commonwealth Games.[18]

Gallery

edit-

View of East gate entry from inside the courtyard of Begumpur Masjid

-

Closer view of East gate of Begumpur Masjid

-

Begampur Masjid West wall and North wall

-

Begumpur Masjid Courtyard and the small domes on the roof

-

Begumpur Masjid Mihrabs under main west wall

-

Baradari

-

Wall mosque near Lal Gumbad

References

edit- ^ a b c Madan Mohan. "Historical Information System for Surveying Monuments and Spatial Data Modeling for Conservation of Cultural Heritage in Delhi" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 February 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- ^ Aitken, Bill (2001) [2002]. Speaking Stones: World Cultural Heritage Sites in India. Eicher Goodearth Limited. p. 25. ISBN 81-87780-00-2. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

"Whatever the cause of Tughalqabad's demise, Ghiyasuddin's successor Mohammed Bin Tughlaq returned to the original Rajput site. However, the Mongol threatened again and the new ruler decided to wall Qila Rai Pihora, Siri and the suburbs between them to build his Jahanpnah or "Refuge of the World"

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c "Adilabad - The Fourth Fort of Delhi". Archived from the original on 2 January 2008. Retrieved 19 May 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Y.D.Sharma (2001). Delhi and its Neighbourhood. New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 25 & 73. Archived from the original on 31 August 2005. Retrieved 24 April 2009.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Lucy Peck (2005). Delhi - A thousand years of Building. New Delhi: Roli Books Pvt Ltd. pp. 58–69. ISBN 81-7436-354-8.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b "Begumpuri Masjid". Archived from the original on 5 July 2009. Retrieved 24 May 2009.

- ^ Verma, Amrit (1985). Forts of India. New Delhi: The Director of Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 7. ISBN 81-230-1002-8.

- ^ "Forts of Delhi". Retrieved 19 May 2009.

- ^ Peter Jackson (2003). The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History. Cambridge University Press. pp. 259–260. ISBN 9780521543293. Retrieved 23 May 2009.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Commonwealth Games-2010, Conservation, Restoration and Upgradation of Public Amenities at Protected Monuments" (PDF). Adilabad Fort. Archaeological Survey of India, Delhi Circle. 2006. p. 65. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2011. Retrieved 29 May 2009.

- ^ a b Anthony Welch; Howard Crane (1983). "The Tughluqs: Master Builders of the Delhi Sultanate" (PDF). Muqarnas. 1. Brill: 129–130. doi:10.2307/1523075. JSTOR 1523075. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 August 2016. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ^ a b James D. Tracy, ed. (2000). "Chapter 9 Delhi walled: Changing boundaries". City Walls: The Urban Enceinte in Global Perspective. Cambridge University Press. pp. 264–268. ISBN 978-0-521-65221-6.

- ^ a b c Anthony Welch; Howard Crane (1983). "The Tughluqs: Master Builders of the Delhi Sultanate" (PDF). Muqarnas. 1. Brill: 148–149. doi:10.2307/1523075. JSTOR 1523075. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 August 2016. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ^ "Kalu Sarai Masjid". Archived from the original on 6 July 2009. Retrieved 24 May 2009.

- ^ Lucy Peck (2005). Delhi - A thousand years of Building. New Delhi: Roli Books Pvt Ltd. p. 63. ISBN 81-7436-354-8. Archived from the original on 6 October 2008. Retrieved 19 May 2009.

The Lal Gumbad itself is very similar to the tomb of Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq (died 1324), although it was built much later in the century for Shiekh Kabiruddin Auliya, a disciple of Chiragh Delhi

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Baradari at Sadhana Enclave". Government of NCT of Delhi. Archived from the original on 17 April 2008. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- ^ Richi, Verma (14 July 2009). "13 structures notified by archaeology dept". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ "Commonwealth Games-2010, Conservation, Restoration and Upgradation of Public Amenities at Protected Monuments" (PDF). Jahapanah Wall. Archaeological Survey of India, Delhi Circle. 2006. p. 54. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2011. Retrieved 29 May 2009.