Dalmatae: Difference between revisions

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

* [[Cohors VI Delmatarum equitata]] |

* [[Cohors VI Delmatarum equitata]] |

||

* [[Cohors VII Delmatarum equitata]] |

* [[Cohors VII Delmatarum equitata]] |

||

* And later the [[Equites Dalmatae]] |

|||

==Religion== |

==Religion== |

||

Revision as of 21:12, 16 January 2012

| History of Dalmatia |

|---|

|

| History of Croatia |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

| History of Bosnia and Herzegovina |

|---|

|

|

|

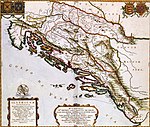

The Dalmatae[1] or Delmatae were an ancient people who inhabited the core of what would then become known as Dalmatia after the Roman conquest - now the eastern Adriatic coast in Croatia, between the rivers Krka and Neretva. The Delmatae are mostly classed as an Illyrian[2] tribe, although for most of their history they were independent of the Illyrian kingdom which bordered to the southeast of them.

Name

The name Dalmatae is connected with the Illyrian word delmë, dele in modern Albanian, which means sheep in English.[3] The Illyrian town of Delminium has the same etymology.[4]

Culture and Society

Archaeology and onomastic shows that the Delmatae were akin to eastern Illyrians and northern Pannonii.[5] Delmatae were a younger nomadic[citation needed] tribe in ancient Illyria (West Balkans); they emerged there since 4th century BC, partly repulsing[citation needed] from their area the earlier peoples of Liburni westwards, Daorsi and Ardiaei (Vardaei) eastwards. They were formed as a tribal alliance[citation needed] of culturally similar communities in 4th-3rd century BC, like the Tariotes and the others. The tribe was subject to Celtic influences.[6][7].One of the Dalmatian tribes was called Baridustae[8] that later was settled in Roman Dacia.

The archeological remnants suggest their material culture was more primitive than this one of the surrounding ancient tribes, especially in comparison with the oldest Liburnians. Only their production of weapons was rather advanced. Their elite had the build stone houses only, but numerous Delmatic herdmen yet settled in natural caves, and a characteristic detail in their usual clothing was the fur cap.

Their nomadic society had a strong patriarchal structure, consisting chiefly of shepherds, warriors and their chieftains. Their main jobs had been the extensive cattle breeding, and the iterative plundering of other surrounding tribes and of coastal towns at Adriatic. The early independent Delmatae had been completely illiterate[citation needed], and the first inscriptions there appeared since the Roman conquest.

Roman conquest

There were some iterative Roman conflicts with the Delmatae lasting for 160 years. The main reason was the perpetual aggressiveness of nomadic Delmatae against all their neighbours (Liburni, Daorsi, Ardiei, etc.), and also towards the Issaean federation[citation needed], Greek-led Roman allies in central Adriatic islands, and so their pacification appeared inevitable. Delmatae land was mostly a rocky calcareous country with many pathless mountains, ideal for infinite guerilla wars; thus Delmatae erected[citation needed] there about 400 stony forteresses and 50 major citadels against Romans.[9]

The first Dalmatian war[citation needed] in 156 BC – 155 BC finished with the destruction of capital Delminium by consul Scipio Nasica. The second Dalmatian war[citation needed] was fought in 119–118 BC, apparently ending in Roman victory as consul L. Caecilius Metellus celebrated triumph in 117 BC and assumed his surname Delmaticus. The third Dalmatian war 78 BC - 76 BC finished with the capture of Salona[10] (port Solin near modern city Split) by the proconsul C. Cosconius.

During the Roman Civil war of 49 BC - 44 BC, the Delmatae (led[citation needed] by Versos and Testimos) sided with Pompey and continuously fought against the Caesarian generals Gabinius and Vatinius. The fourth and final conflict occurred 34 BC - 33 BC during Octavian's expedition to Illyricum because of their iterative revolts, and finished with the capture of the new Delmatian capital- Soetovio (now Klis). The last revolts of Delmatae under their federal leader Baton, against Romans were in 12 BC and the Great Illyrian Revolt in 6-9 AD; both also failed and finished by a terminal pacification of bellicose Delmatae.

Afterwards, the Dalmatae formed numerous Roman auxiliaries:

- Cohors I Delmatarum

- Cohors I Delmatarum milliaria equitata

- Cohors II Delmatarum

- Cohors III Delmatarum equitata c.R. pf

- Cohors IV Delmatarum

- Cohors V Delmatarum

- Cohors V Delmatarum c.R.

- Cohors VI Delmatarum equitata

- Cohors VII Delmatarum equitata

- And later the Equites Dalmatae

Religion

The major collective deity of Delmatic federation was their pastoral god 'Sylvanus' they called Vidasus[11]. His divine wife was 'Thana' [12], a Delmatic goddess mostly comparable with Roman Diana and Greek Artemis. Their frequent reliefs often accompanied by nymphs, are partly conserved up today in some cliffs of Dalmatia; in Imotski valley also their temple used from 4th to 1st century BC, was unearthed. The third important one of Delmatae was a wargod 'Armatus' comparable with Roman Mars and Greek Ares. Their bad deity was the celestial Dragon[citation needed] devouring the sun or moon in the eclipses.

A strong weapons cult was very specific for the patriarchal Delmatae, and in their masculine tombs different weapons are widely present (that is rare in neighbouring peoples e.g. Liburni, Iapydes, etc.). Their usual tombs were under the stone tumuli of kurgan type. After the classic Roman reports (Muzic 1998), nomadic Delmatae were extremely superstitious, and they had a primitive panic dread[citation needed] from all celestial phenomena: any view on the night stars was them forbidden in the fear of a sure death, and in the case of solar or lunar eclipses they repeated tremendous collective howling because of the immediate world ending, made hysterical suicides etc.

Linguistic affinity

The ancient Dalmatian language was part of the Illyrian languages, which were spoken in the western part of the Balkans.[13] The name Dalmatae is connected with the Albanian word delmë, which means sheep in English.[3] During the Celtic settlements in the Balkans the Dalmatian language was partly influenced by the Celtic language regarding personal names and toponyms.[13]

The original language of the early Delmatae is scarcely known save a few toponyms noted by the Romans. Since the Roman conquest, town-dwelling Dalmatae were gradually Romanized, but shepherds in the countryside were assimilated more slowly and only partially. After the collapsed of the Roman Empire, Dalmatian citizens continued to partly speak the Old Dalmatic Romance language (intermediary one between Italian and Rumanian).

The medieval descendants of pastoral Delmatae in Dalmatian inlands conserved (at least partly) an Eastern Romance tongue (see Istro-Romanian language) with a large number of Slavic loanwords, called Morlachian dialect (Murlaška besida), persisting also in the Austrian Empire; it was chiefly spoken by 2100 local shepherds around the recent town of Livno up to World War I. Then in Yugoslavia during 20th century these non-Slavic pastorals under oppression were quickly slavicized. What remains of their language is but a few curious non-Slavic toponyms around the Livno valley, e.g. the rivulets Ayvatat, Suturba, and mountain peaks Bleynadorna, Brona, Ozirna, Gareta, Mitra, Zugva, Drul, Yenit, Yunch, Chamasir, and others.

Literature

- Issa-Fatimi, Aziz & Yoshamya, Zyelimer: Kurdish-Croat-English glossary of dialects Dimili and Kurmanji, and their biogenetic comparison. Scientific society for Ethnogenesis studies, Zagreb 2006 (in press).

- Lovric, A.Z. et al.: The Ikavic Schakavians in Dalmatia (glossary, culture, genom). Old-Croatian Archidioms, Monograph 3 (in press), Scientific society for Ethnogenesis studies, Zagreb 2007.

- Muzic, Ivan: Autoctonia e prereligione sul suolo della provincia Romana di Dalmazia. Accademia Archeologica Italiana, Roma 1994 (5th edition: Slaveni, Goti i Hrvati na teritoriju rimske provincije Dalmacije Zagreb 1998, 599 p.)

- Zaninovic, M.: Ilirsko pleme Delmati. Godišnjak (Annuaire) 4-5, 27 p., Centar za balkanološke studije, Sarajevo 1966–1967.

See also

References

- ^ Δαλμάται in Medieval Greek.

- ^ The Cambridge Ancient History Vol. 11: The High Empire, AD 70-192 by Peter Rathbone, page 597, "... One such place was Delminium, from which the Illyrian Delmatae took their name, attacked more than once by Roman consuls ..."

- ^ a b Wilkes, John (1995). The Illyrians. The Peoples of Europe. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 244. ISBN 0631198075.

- ^ Stipčević, Aleksandar (1977). The Illyrians: History and Culture. History and Culture Series. Noyes Press. p. 197. ISBN 0815550529.

- ^ The Illyrians by J. J. Wilkes, 1992, ISBN 0631198075, Page 70, "... on Pannonia (1959) and Moesia Superior (1970). Duje Rendic-Miocevic has published several studies of names from the territory of the Delmatae, ..."

- ^ The Oxford Classical Dictionary by Simon Hornblower and Antony Spawforth, 2003, page 426.

- ^ A dictionary of the Roman Empire Oxford paperback reference, ISBN-0195102339, 1995, page 202, "contact with the peoples of the Illyrian kingdom and at the Celticized tribes of the Delmatae ..."

- ^ Roman Dacia: the making of a provincial society by W. S. Hanson, Ian Haynes, 2004, page 22, "Outside the main urban centres, the best attested group of civilian immigrants is members of the Dalmatian tribes such as the Baridustae"

- ^ The Illyrians by J. J. Wilkes, 1992, ISBN 0631198075, page 203, "... the later Siscia (Sisak), in the same year that the Romans first attacked the Delmatae. The general scarcity of references to Pannonians may be a reflection of their subjection to the Scordisci. ..."

- ^ The Illyrians by John Wilkes p.196

- ^ The Illyrians by J. J. Wilkes, 1992, ISBN 0631198075, page 247, "... Death among Illyrians 247 identities of Silvanus and Diana, a familiar combination on many dedications in the territory of the Delmatae. Sometimes the name of a local deity is recorded only in the Latin form, for example, ..."

- ^ Wilkes. "North of the Japodes, the altars to Vidasus and Thana dedicated at the hot springs of Topusko reveal the local Roman Illyrians..."

- ^ a b Boardman, John (1982). The prehistory of the Balkans and the Middle East and the Aegean world, tenth to eighth centuries B.C. The Prehistory of the Balkans. Vol. 3. Cambridge University Press. p. 866. ISBN 0521224969.

External links

- Articles needing cleanup from September 2009

- Cleanup tagged articles without a reason field from September 2009

- Wikipedia pages needing cleanup from September 2009

- Illyrian tribes

- Ancient peoples

- Indo-European peoples

- Illyrian Croatia

- Ancient tribes in Croatia

- History of Dalmatia

- Ancient tribes in Bosnia and Herzegovina