Economy of Thailand

| |

| Currency | Thai baht (THB, ฿) |

|---|---|

| 1 October – 30 September | |

Trade organisations | WTO, APEC, IOR-ARC, ASEAN, RCEP |

Country group |

|

| Statistics | |

| Population | |

| GDP | |

| GDP rank | |

GDP growth | |

GDP per capita | |

GDP per capita rank | |

GDP by sector |

|

| 5.02% (Jan 2023) | |

Population below poverty line | |

| |

Labour force | |

| Unemployment | |

Average gross salary | ฿15,352 / US$437 monthly |

| ฿14,505 / US$413 monthly | |

Main industries | Automobiles and automotive parts (11%), financial services (9%), electric appliances and components (8%), tourism (6%), cement, auto manufacturing, heavy and light industries, appliances, computers and parts, furniture, plastics, textiles and garments, agricultural processing, beverages, tobacco |

| External | |

| Exports | $287.42 billion (2023)[14] |

Export goods | machinery (23%), electronics (19%), foods and wood (14%), chemicals and plastics (14%), automobiles and automotive parts (12%), stone and glass (7%), textiles and furniture (4%) |

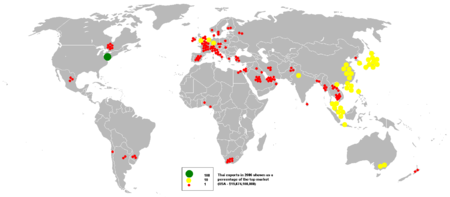

Main export partners |

|

| Imports | $303.19 billion (2022)[14] |

Import goods | Capital and intermediate goods, raw materials, consumer goods, fuels |

Main import partners |

|

FDI stock | $205.5 billion (2017 est.)[15] |

Gross external debt | $163.40 billion (Q1 2019)[16] |

| Public finances | |

| 61.85% of GDP (2023)[17] | |

| Revenues | ฿2.664 trillion (FY2023)[18] |

| Expenses | ฿2.610 trillion (FY2023)[19] |

| Economic aid | None |

| |

| $250.98 billion (net amount, 12/04/2024)[24] | |

All values, unless otherwise stated, are in US dollars. | |

The economy of Thailand is dependent on exports, which accounted in 2021 for about 58 per cent of the country's gross domestic product (GDP).[25] Thailand itself is a newly industrialized country, with a GDP of 17.922 trillion baht (US$514.8 billion) in 2023, the 9th largest economy in Asia.[26] As of 2018, Thailand has an average inflation of 1.06%[27] and an account surplus of 7.5% of the country's GDP.[28] Its currency, the baht, is ranked as the tenth most frequently used world payment currency in 2017.[29]

The industrial and service sectors are the main sectors in the Thai gross domestic product, with the former accounting for 39.2 percent of GDP. Thailand's agricultural sector produces 8.4 percent of GDP—lower than the trade and logistics and communication sectors, which account for 13.4 percent and 9.8 percent of GDP respectively. The construction and mining sector adds 4.3 percent to the country's gross domestic product. Other service sectors (including the financial, education, and hotel and restaurant sectors) account for 24.9 percent of the country's GDP.[6] Telecommunications and trade in services are emerging as centers of industrial expansion and economic competitiveness.[30]

Thailand is the second-largest economy in Southeast Asia, after Indonesia. Its per capita GDP 255,362 baht (US$7,336) in 2023[26] ranks fourth in Southeast Asian per capita GDP, after Singapore, Brunei, and Malaysia. In July 2018, Thailand held US$237.5 billion in international reserves,[31] the second-largest in Southeast Asia (after Singapore). Its surplus in the current account balance ranks tenth of the world, made US$37.898 billion to the country in 2018.[32] Thailand ranks second in Southeast Asia in external trade volume, after Singapore.[33]

The nation is recognized by the World Bank as "one of the great development success stories" in social and development indicators.[34] Despite a per capita gross national income (GNI) of US$7,090[35] and ranking 66th in the Human Development Index (HDI), the percentage of people below the national poverty line decreased from 65.26 percent in 1988 to 8.61 percent in 2016, according to the Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council's (NESDC) new poverty baseline.[36]

Thailand is one of the countries with the lowest unemployment rates in the world, reported as one percent for the first quarter of 2014. This is due to a large proportion of the population working in subsistence agriculture or on other vulnerable employment (own-account work and unpaid family work).[37]

Kingdom of Thailand budget

[edit]The Kingdom of Thailand's FY2017 budget was 2,733,000 trillion baht.[38]

In May 2018, the Thai Cabinet approved a FY2019 budget of three trillion baht, up 3.4 percent—100 billion baht—from FY2018. Annual revenue is projected to reach 2.55 trillion baht, up 4.1 percent, or 100 billion baht. Overall, the national budget will face a deficit of 450 billion baht. The cabinet also approved a budget deficit until 2022 in order to drive the economy to a growth of 3.5–4.5 percent a year.[39]

History

[edit]

Before 1945

[edit]Thailand, formerly known as Siam, opened to foreign contact in the pre-industrial era. Despite the scarcity of resources in Siam, coastal ports and cities and those at the river mouth were early economic centers which welcomed merchants from Persia, the Arab countries, India, and China. The rise of Ayutthaya during the 14th century was connected to renewed Chinese commercial activity, and the kingdom became one of the most prosperous trade centers in Asia.

When the capital of the kingdom moved to Bangkok during the 19th century, foreign trade (particularly with China) became the focus of the government. Chinese merchants came to trade; some settled in the country and received official positions. A number of Chinese merchants and migrants became high dignitaries in the court.

From the mid-19th century onward, European merchants were increasingly active. The Bowring Treaty, signed in 1855, guaranteed the privileges of British traders. The Harris Treaty of 1856, which updated the Roberts Treaty of 1833, extended the same guarantees to American traders.

The domestic market developed slowly, with serfdom a possible cause of domestic stagnation. Most of the male population in Siam was in the service of court officials, while their wives and daughters may have traded on a small scale in local markets. Those who were heavily indebted might sell themselves as slaves. King Rama V abolished serfdom and slavery in 1901 and 1905, respectively.

From the early 20th century to the end of World War II, Siam's economy gradually became globalized. Major entrepreneurs were ethnic Chinese who became Siamese nationals. Exports of agricultural products (especially rice) were very important and Thailand has been among the top rice exporters in the world. The Siamese economy suffered greatly from the Great Depression, a cause of the Siamese revolution of 1932.[40]

Significant investment in education in the 1930s (and again in the 1950s) laid the basis for economic growth, as did a liberal approach to trade and investment.[41]

After 1945

[edit]1945–1955

[edit]Postwar domestic and international politics played significant roles in Thai economic development for most of the Cold War era. From 1945 to 1947 (when the Cold War had not yet begun), the Thai economy suffered because of the Second World War. During the war, the Thai government (led by Field Marshal Luang Phibulsongkram) allied with Japan and declared war against the Allies. After the war, Thailand had to supply 1.5 million tons of rice to Western countries without charge, a burden on the country's economic recovery. The government tried to solve the problem by establishing a rice office to oversee the rice trade. During this period, a multiple-exchange-rate system was introduced amid fiscal problems, and the kingdom experienced a shortage of consumer goods.[42]

In November 1947, a brief democratic period was ended by a military coup and the Thai economy regained its momentum. In his dissertation, Somsak Nilnopkoon considers the period from 1947 to 1951 one of prosperity.[42] By April 1948, Phibulsongkram, the wartime prime minister, returned to his previous office. However, he was caught in a power struggle between his subordinates. To preserve his power, Phibulsongkram began an anti-communist campaign to seek support from the United States.[43] As a result, from 1950 onward, Thailand received military and economic aid from the US. The Phibulsongkram government established many state enterprises, which were seen as economic nationalism. The state (and its bureaucrats) dominated capital allocation in the kingdom. Ammar Siamwalla, one of Thailand's most prominent economists, calls it the period of "bureaucratic capitalism".[43]

1955–1985

[edit]In 1955, Thailand began to see a change in its economy fueled by domestic and international politics. The power struggle between the two main factions of the Phibul regime—led by Police General Phao Sriyanond and General (later, Field Marshal) Sarit Thanarat—increased, causing Sriyanonda to unsuccessfully seek support from the US for a coup against Phibulsongkram regime. Luang Phibulsongkram attempted to democratize his regime, seeking popular support by developing the economy. He again turned to the US, asking for economic rather than military aid. The US responded with unprecedented economic aid to the kingdom from 1955 to 1959.[43] The Phibulsongkram government also made important changes to the country's fiscal policies, including scrapping the multiple-exchange-rate system in favor of a fixed, unified system which was in use until 1984. The government also neutralized trade and conducted secret diplomacy with the People's Republic of China, displeasing the United States.

Despite his attempts to maintain power, Luang Phibulsongkram was deposed (with Field Marshal Phin Choonhavan and Police General Phao Sriyanond) on 16 September 1957 in a coup led by Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat. The Thanarat regime (in power from 1957 to 1973) maintained the course set by the Phibulsongkram regime with US support after severing all ties with the People's Republic of China and supporting US operations in Indochina. It developed the country's infrastructure and privatized state enterprises unrelated to that infrastructure. During this period, a number of economic institutions were established, including the Bureau of Budget, the NESDC, and the Thailand Board of Investment (BOI). The National Economic and Social Development Plan was implemented in 1961.[44] During this period, the market-oriented Import-Substituting Industrialization (ISI) led to economic expansion in the kingdom during the 1960s.[45] According to former President Richard M. Nixon's 1967 Foreign Affairs article, Thailand entered a period of rapid growth in 1958 (with an average growth rate of seven percent a year).[46]

From the 1970s to 1984, Thailand suffered from many economic problems: decreasing US investment, budget deficits, oil-price spikes, and inflation. Domestic politics were also unstable. With the Vietnamese occupation of Cambodia on 25 December 1978, Thailand became the front-line state in the struggle against communism, surrounded by two communist countries and a socialist Burma under General Ne Win. Successive governments tried to solve the economic problems by promoting exports and tourism, still important for the Thai economy.[47]

One of the best-known measures to deal with the economic problems of that time was implemented under General Prem Tinsulanonda's government, in power from 1980 to 1988. Between 1981 and 1984, the government devalued the national currency, the Thai baht (THB), three times. On 12 May 1981, it was devalued by 1.07 percent, from THB20.775/US$ to THB21/US$. On 15 July 1981, it was again devalued, this time by 8.7 percent (from THB21/US$ to THB23/US$). The third devaluation, on 5 November 1984, was the most significant: 15 percent, from THB23/US$ to THB27/US$.[48] The government also replaced the country's fixed exchange rate (where it was pegged to the US dollar) with a "multiple currency basket peg system" in which the US dollar bore 80 percent of the weight.[49] Calculated from the IMF's World Economic Outlook Database, in the period 1980–1984, the Thai economy had an average GDP growth rate of 5.4 percent.[50]

1985–1997

[edit]Concurrent with the third devaluation of the Thai baht, on 22 September 1985, Japan, the US, the United Kingdom, France, and West Germany signed the Plaza Accord to depreciate the US dollar in relation to the yen and the Deutsche Mark. Since the dollar accounted for 80 percent of the Thai currency basket, the baht was depreciated further, making Thailand's exports more competitive and the country more attractive to foreign direct investment (FDI) (especially from Japan, whose currency had appreciated since 1985). In 1988, Prem Tinsulanonda resigned and was succeeded by Chatichai Choonhavan, the first democratically elected prime minister of Thailand since 1976. The Cambodian-Vietnamese War was ending; Vietnam gradually retreated from Cambodia by 1989, enhancing Thai economic development.

After the 1984 baht devaluation and the 1985 Plaza Accord, although the public sector struggled due to fiscal constraints, the private sector grew. The country's improved foreign trade and an influx of foreign direct investment (mainly from Japan) triggered an economic boom from 1987 to 1996. Although Thailand had previously promoted its exports, during this period the country shifted from import-substitution (ISI) to export-oriented industrialization (EOI). During this decade the Thai GDP (calculated from the IMF World Economic Outlook database) had an average growth rate of 9.5 percent per year, with a peak of 13.3 percent in 1988.[50] In the same period, the volume of Thai exports of goods and services had an average growth rate of 14.8 percent, with a peak of 26.1 percent in 1988.[50]

Economic problems persisted. From 1987 to 1996, Thailand experienced a current account deficit averaging −5.4 percent of GDP per year, and the deficit continued to increase. In 1996, the current account deficit accounted for −7.887 percent of GDP (US$14.351 billion).[50] A shortage of capital was another problem. The first Chuan Leekpai government, in office from September 1992 to May 1995, tried to solve this problem by granting Bangkok International Banking Facility (BIBF) licenses to Thai banks in 1993. This allowed BIBF banks to benefit from Thailand's high-interest rate by borrowing from foreign financial institutions at low interest and loaning to Thai businesses. By 1997, foreign debt had risen to US$109,276 billion (65% of which was short-term debt), while Thailand had US$38,700 billion in international reserves.[51] Many loans were backed by real estate, creating an economic bubble. By late 1996, there was a loss of confidence in the country's financial institutions; the government closed 18 trust companies and three commercial banks. The following year, 56 financial institutions were closed by the government.[51]

Another problem was foreign speculation. Aware of Thailand's economic problems and its currency basket exchange rate, foreign speculators (including hedge funds) were certain that the government would again devalue the baht, under pressure on both the spot and forward markets. In the spot market, to force devaluation, speculators took out loans in baht and made loans in dollars. In the forward market, speculators (believing that the baht would soon be devalued) bet against the currency by contracting with dealers who would give dollars in return for an agreement to repay a specific amount of baht several months in the future.[52]

In the government, there was a call from Virapong Ramangkul (one of Prime Minister Chavalit Yongchaiyudh's economic advisers) to devalue the baht, which was supported by former Prime Minister Prem Tinsulanonda.[53] Yongchaiyudh ignored them, relying on the Bank of Thailand (led by Governor Rerngchai Marakanond, who spent as much as US$24,000 billion – about two-thirds of Thailand's international reserves) to protect the baht. On 2 July 1997, Thailand had US$2,850 billion remaining in international reserves,[51] and could no longer protect the baht. That day Marakanond decided to float the baht, triggering the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis.

1997–2000

[edit]

The Thai economy collapsed as a result of the 1997 Asian financial crisis. Within a few months, the value of the baht floated from THB25/US$ (its lowest point) to THB56/US$. The Stock Exchange of Thailand (SET) dropped from a peak of 1,753.73 in 1994 to a low of 207.31 in 1998.[54] The country's GDP dropped from THB3.115 trillion at the end of 1996 to THB2.749 trillion at the end of 1998. In dollar terms, it took Thailand as long as 10 years to regain its 1996 GDP. The unemployment rate went up nearly threefold: from 1.5 percent of the labor force in 1996 to 4.4 percent in 1998.[55]

A sharp decrease in the value of the baht abruptly increased foreign debt, undermining financial institutions. Many were sold, in part, to foreign investors while others went bankrupt. Due to low international reserves from the Bank of Thailand's currency-protection measures, the government had to accept a loan from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Overall, Thailand received US$17.2 billion in aid.[56]

The crisis impacted Thai politics. One direct effect was that Prime Minister Chavalit Yongchaiyudh resigned under pressure on 6 November 1997, succeeded by opposition leader Chuan Leekpai. The second Leekpai government, in office from November 1997 to February 2001, tried to implement economic reforms based on IMF-guided neo-liberal capitalism. It pursued strict fiscal policies (keeping interest rates high and cutting government spending), enacting 11 laws it called "bitter medicine" and critics called "the 11 nation-selling laws". The Thai government and its supporters maintained that with these measures, the Thai economy improved.

In 1999, Thailand had a positive GDP growth rate for the first time since the crisis. [citation needed] Many critics, however, mistrusted the IMF and maintained that government-spending cuts harmed the recovery. Unlike economic problems in Latin America and Africa, they asserted, the Asian financial crisis was born in the private sector and the IMF measures were inappropriate. The positive growth rate in 1999 was because the country's GDP had gone down for two consecutive years, as much as −10.5 percent in 1998 alone. In terms of the baht, it was not until 2002 (in dollar terms, not until 2006) that Thailand would regain its 1996 GDP. An additional 1999 loan from the Miyazawa Plan made the question of whether (or to what extent) the Leekpai government helped the Thai economy controversial.

Recent economic history (2001–present)

[edit]An indirect effect of the financial crisis on Thai politics was the rise of Thaksin Shinawatra. In reaction to the government's economic policies, Thaksin Shinawatra's Thai Rak Thai Party won a landslide victory over Leekpai's Democrat Party in the 2001 general election and took office in February 2001. Although weak export demand held the GDP growth rate to 2.2 percent in the first year of his administration, the first Thaksin Shinawatra government performed well from 2002 to 2004 with growth rates of 5.3, 7.1 and 6.3 percent respectively. His policy was later called Thaksinomics. During Thaksin's first term, Thailand's economy regained momentum and the country paid its IMF debt by July 2003 (two years ahead of schedule). Despite criticism of Thaksinomics, Thaksin's party won another landslide victory over the Democrat Party in the 2005 general election. The official economic data related to Thaksinomics reveals that between 2001 and 2011, Isan's GDP per capita more than doubled to US$1,475, while, over the same period, GDP in the Bangkok area rose from US$7,900 to nearly US$13,000.[57]

Thaksin's second term was less successful. On 26 December 2004, the Indian Ocean tsunami occurred. In addition to the human toll, it impacted the first-quarter Thai GDP in 2005. The Yellow Shirts, a coalition of protesters against Thaksin, also emerged in 2005. In 2006, Thaksin dissolved the parliament and called for a general election. The April 2006 general election was boycotted by the main opposition parties. Thaksin's party won again, but the election was declared invalid by the Constitutional Court. Another general election, scheduled for October 2006, was cancelled. On 19 September a group of soldiers calling themselves the Council for Democratic Reform under the Constitutional Monarchy and led by Sonthi Boonyaratglin organized a coup, ousting Thaksin while he was in New York preparing for a speech at the United Nations General Assembly. During the last year of the second Thaksin government, the Thai GDP grew by 5.1 percent. Under his governments, Thailand's overall ranking in the IMD Global Competitiveness Scoreboard rose from 31st in 2002 to 25th in 2005 before falling to 29th in 2006.[58]

After the coup, Thailand's economy again suffered. From the last quarter of 2006 through 2007, the country was ruled by a military junta led by General Surayud Chulanont, who was appointed prime minister in October 2006. The 2006 GDP growth rate slowed from 6.1, 5.1 and 4.8 percent year-over-year in the first three-quarters to 4.4 percent (YoY) in Q4.[59] Thailand's ranking on the IMD Global Competitiveness Scoreboard fell from 26th in 2005 to 29th in 2006 and 33rd in 2007.[58] Thaksin's plan for massive infrastructure investments was unmentioned until 2011, when his younger sister Yingluck Shinawatra entered office. In 2007, the Thai economy grew by 5 percent. On 23 December 2007, the military government held a general election. The pro-Thaksin People's Power Party, led by Samak Sundaravej, won a landslide victory over Abhisit Vejjajiva's Democrat Party.

Under the People's Power Party-led government the country fell into political turmoil. This, combined with the financial crisis of 2007–2008 cut the 2008 Thai GDP growth rate to 2.5%.[59] Before the People's Alliance for Democracy (PAD) and the Yellow Shirts reconvened in March 2008, the GDP grew by 6.5 percent (YoY) in the first quarter of the year.[59] Thailand's ranking on the IMD World Competitiveness Scoreboard rose from 33rd in 2007 to 27th in 2008. The Yellow Shirts occupied the Government House of Thailand in August 2008, and on 9 September the Constitutional Court delivered a decision removing Samak Sundaravej from the prime ministership.

Somchai Wongsawat, Thaksin's brother-in-law, succeeded Samak Sundaravej as prime minister on 18 September. In the US the financial crisis reached its peak while the Yellow Shirts were still in Government House, impeding government operations. GDP growth dropped from 5.2 percent (YoY) in Q2 2008 to 3.1 percent (YoY) and −4.1 percent (YoY) in Q3 and Q4. From 25 November to 3 December 2008 the Yellow Shirts, protesting Somchai Wongsawat's prime ministership, seized the two Bangkok airports, (Suvarnabhumi and Don Mueang), and damaged Thailand's image and economy. On 2 December the Thai Constitutional Court issued a decision dissolving the People's Power Party, ousting Somchai Wongsawat as prime minister.

By the end of 2008, a coalition government led by Abhisit Vejjajiva's Democrat Party was formed: "[The] legitimacy of the Abhisit government has been questioned since the first day that the Democrat party took the office in 2008 as it was allegedly formed by the military in a military camp".[60] The government was under pressure from the US financial crisis and the Red Shirts, who refused to acknowledge Abhisit Vejjajiva's prime ministry and called for new elections as soon as possible. However, Abhisit rejected the call until he dissolved the parliament for a new election in May 2011. In 2009, his first year in office, Thailand experienced a negative growth rate for the first time since the 1997 financial crisis: a GDP of −2.3 percent.[59]

In 2010, the country's growth rate increased to 7.8 percent. However, with the instability surrounding the major 2010 protests, the GDP growth of Thailand settled at around 4–5 percent from highs of 5–7 percent under the previous civilian administration—political uncertainty was identified as the primary cause of a decline in investor and consumer confidence. The IMF predicted that the Thai economy would rebound strongly from the low 0.1 percent GDP growth in 2011, to 5.5 percent in 2012 and then 7.5 percent in 2013, due to the accommodating monetary policy of the Bank of Thailand, as well as a package of fiscal stimulus measures introduced by the incumbent Yingluck Shinawatra government.[61]

In the first two-quarters of 2011, when the political situation was relatively calm, the Thai GDP grew by 3.2 and 2.7 percent (YoY).[59] Under Abhisit's administration, Thailand's ranking fell from 26 in 2009, to 27 in 2010 and 2011,[58] and the country's infrastructure declined since 2009.[58]

In the 2011 general election, the pro-Thaksin Pheu Thai Party again won a decisive victory over the Democrat Party, and Thaksin's youngest sister, Yingluck Shinawatra, succeeded Abhisit as prime minister. Elected in July, the Pheu Thai Party-led government began its administration in late-August, and when Yingluck entered office, the 2011 Thailand floods threatened the country—from 25 July 2011 to 16 January 2012, flood waters covered 65 of the country's 76 provinces. The World Bank assessed the total damage in December 2011 and reported a cost of THB1.425 trillion (about US$45.7 billion).[62]

The 2011 GDP growth rate fell to 0.1 percent, with a contraction of 8.9 percent (YoY) in Q4 alone.[63] The country's overall competitiveness ranking, according to the IMD World Competitiveness Scoreboard, fell from 27 in 2011 to 30 in 2012.[64]

In 2012, Thailand was recovering from the previous year's severe flood. The Yingluck government planned to develop the country's infrastructure, ranging from a long-term water-management system to logistics. The Eurozone crisis reportedly harmed Thailand's economic growth in 2012, directly and indirectly affecting the country's exports. Thailand's GDP grew by 6.5 percent, with a headline inflation rate of 3.02 percent, and a current account surplus of 0.7 percent of the country's GDP.[65]

On 23 December 2013, the Thai baht dropped to a three-year low due to the political unrest during the preceding months. According to Bloomberg, the Thai currency lost 4.6 percent over November and December, while the main stock index also dropped (9.1 percent).[66]

Following the Thai military coup in May 2014, Agence France Presse (AFP) published an article that claimed that the nation was on the "verge of recession". Published on 17 June 2014, the article's main subject is the departure of nearly 180,000 Cambodians from Thailand due to fears of an immigration "clampdown", but concluded with information on the Thai economy's contraction of 2.1 percent quarter-on-quarter, from January to the end of March 2014.[67]

Since the cessation of the curfew that was enacted by the military in May 2014, the Federation of Thai Industries (FTI)'s chairman, Supant Mongkolsuthree, said that he projects growth of 2.5–3 percent for the Thai economy in 2014, as well as a revitalisation of the Thai tourist industry in the second half of 2014. Furthermore, Supant also cited the Board of Investment's future consideration of a backlog of investment projects, estimated at about 700 billion baht, as an economically beneficial process that would occur around October 2014.[68] Thailand's flagging economic performance led, at the end of 2015, to increased criticism of the National Council for Peace and Order's (NCPO) handling of the economy, both at home and in influential Western media.[69][70] The country's economic growth of 2.8% in the first quarter of 2019 was recorded to be the slowest since 2014.[71]

The military government unveiled its newest economic initiative, "Thailand 4.0", in 2016. Thailand 4.0 is the "...master plan to free Thailand from the middle-income trap, making it a high-income nation in five years."[72]

The government narrative describes Thailand 1.0 as the agrarian economy of Thailand decades ago. Thailand 1.0 gave way to Thailand 2.0, when the nation's economy moved on to light industry, textiles, and food processing. Thailand 3.0 describes the present day, with heavy industry and energy accounting for up to 70 percent of the Thai GDP.[72] Thailand 4.0 is described as an economy driven by high-tech industries and innovation that will lead to the production of value-added products and services. According to General Prayut Chan-o-cha, the prime minister, Thailand 4.0 is composed of three elements: 1. Make Thailand a high-income nation, 2. Make Thailand a more inclusive society, and 3. Focus on sustainable growth and development.[73]

Critics of Thailand 4.0 point out that Thailand lacks the specialists and experts, especially in high-technology, needed to modernise Thai industry. "...the government will have to allow the import of foreign specialists to help bring forward Thailand 4.0," said Somchai Jitsuchon, research director for inclusive development at the Thailand Development Research Institute (TDRI). "...that won't be easy as local professional associations will oppose the idea as they want to reserve those professional careers for Thais only".[72] He went on to point out that only 56 percent of Thailand's population has access to the Internet, an obstacle to the creation of a high-tech workforce. A major thrust of Thailand 4.0 is encouraging a move to robotic manufacturing. But Thailand's membership in the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC), makes cheap workers from neighbouring countries even more readily available, which will make it harder to make the economic case to switch to robots. Somchai also pointed out that the bureaucratic nature of the Thai government will make realisation of Thailand 4.0 difficult. Every action plan calls for results from several ministries, "all of which are big, clumsily-run organisations" slow to perform.[72]

In September 2020, World Bank forecast that Thai economy would contract 8.9% by the end of the year due to COVID-19 pandemic.[74] The Thai government cut jet fuel tax since February 2020.[citation needed]

In August 2024, the dismissal of Thai Prime Minister Srettha Thavisin exacerbated Thailand's economic difficulties, impeding the implementation of significant financial measures. This political upheaval intensified existing issues such as high household debt and economic stagnation, further undermining investor confidence and economic stability.[75]

Macroeconomic trends

[edit]The following table shows the main economic indicators in 1980–2021 (with IMF staff estimates in 2022–2027). Inflation under 5% is in green.[76]

| Year | GDP

(in Bil. US$PPP) |

GDP per capita

(in US$ PPP) |

GDP

(in Bil. US$nominal) |

GDP per capita

(in US$ nominal) |

GDP growth

(real) |

Inflation rate

(in Percent) |

Unemployment

(in Percent) |

Government debt

(in % of GDP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 74.7 | 1,576.1 | 33.4 | 705.5 | n/a | n/a | ||

| 1981 | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| 1982 | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| 1983 | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| 1984 | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| 1985 | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| 1986 | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| 1987 | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| 1988 | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| 1989 | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| 1990 | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| 1991 | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| 1992 | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| 1993 | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| 1994 | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| 1995 | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| 1996 | n/a | 15.2% | ||||||

| 1997 | n/a | |||||||

| 1998 | n/a | |||||||

| 1999 | n/a | |||||||

| 2000 | n/a | |||||||

| 2001 | 3.3% | |||||||

| 2002 | ||||||||

| 2003 | ||||||||

| 2004 | ||||||||

| 2005 | ||||||||

| 2006 | ||||||||

| 2007 | ||||||||

| 2008 | ||||||||

| 2009 | ||||||||

| 2010 | ||||||||

| 2011 | ||||||||

| 2012 | ||||||||

| 2013 | ||||||||

| 2014 | ||||||||

| 2015 | ||||||||

| 2016 | ||||||||

| 2017 | ||||||||

| 2018 | ||||||||

| 2019 | ||||||||

| 2020 | ||||||||

| 2021 | ||||||||

| 2022 | ||||||||

| 2023 | ||||||||

| 2024 | ||||||||

| 2025 | ||||||||

| 2026 | ||||||||

| 2027 |

Over the past 32 years, the economy of Thailand has expanded. The GDP at current prices shows that from 1980 to 2012 the Thai economy has expanded nearly sixteen-fold when measured in baht, or nearly eleven-fold when measured in dollars. This makes Thailand the 32nd-biggest economy in the world, according to the IMF. With regard to GDP, Thailand has undergone five periods of economic growth. From 1980 to 1984, the economy has grown by an average of 5.4 percent per year. Regional businesses account for 70 percent of GDP, with Bangkok contributing 30 percent.[77]

After the 1984 baht devaluation and the 1985 Plaza Accord, a significant amount of foreign direct investment (mainly from Japan) raised the average growth rate per year to 8.8 percent from 1985 to 1996 before slumping to −5.9 percent per year from 1997 to 1998. From 1999 to 2006, Thailand averaged a growth rate of 5.0 percent per year. Since 2007, the country has faced a number of challenges: a military coup in late 2006, political turmoil from 2008 to 2011, the US financial crisis reaching its peak from 2008 to 2009, floods in 2010 and 2011, and the 2012 Eurozone crisis. As a result, from 2007 to 2012 the average GDP growth rate was 3.25 percent per year.

Thailand suffers by comparison with neighboring countries in terms of GDP per capita. In 2011, China's nominal GDP per capita surpassed Thailand's, giving the latter the lowest nominal GDP per capita of its peers. According to the IMF, in 2012 Thailand ranked 92nd in the world in its nominal GDP per capita.

Poverty and inequality

[edit]The number of Thailand's poor declined from 7.1 million people in 2014, 10.5 percent of the population, to 4.9 million people in 2015, or 7.2 percent of the population. Thailand's 2014 poverty line was defined as an income of 2,647 baht per month. For 2015 it was 2,644 baht per month. According to the NESDC in a report entitled, Poverty and Inequality in Thailand, the country's growth in 2014 was 0.8 percent and 2.8 percent in 2015. NESDC Secretary-General Porametee Vimolsiri said that the growth was due to the effect of governmental policies. The report also noted that 10 percent of the Thai population earned 35 percent of Thailand's aggregate income and owned 61.5 percent of its land.[78]

Thailand was ranked as the world's third most unequal nation, behind Russia and India, in the Credit Suisse Global Wealth Databook 2016 (companion volume to the Global Wealth Report 2016[79][failed verification]), with one percent of the Thai population estimated to own 58 percent of Thailand's wealth.[80][81]

Industries

[edit]SMEs

[edit]Virtually all of Thailand's firms, 99.7 percent, or 2.7 million enterprises, are classed as being small or medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). As of 2017[update], SMEs account for 80.3 percent (13 million) of Thailand's total employment. In sheer numbers SMEs predominate, but their contribution to the nation's GDP decreased from 41.3 percent of GDP in 2002 to 37.4 percent in 2013. Their declining contribution is reflected in their turnover rate: seventy percent fail within "...a few years".[82]: 47

Agriculture, forestry and fishing

[edit]

Developments in agriculture since the 1960s have supported Thailand's transition to an industrialised economy.[83] As recently as 1980, agriculture supplied 70 percent of employment.[83] In 2008, agriculture, forestry and fishing contributed 8.4 percent to GDP; in rural areas, farm jobs supply half of employment.[83] Rice is the most important crop in the country and Thailand had long been the world's number one exporter of rice, until recently falling behind both India and Vietnam.[84] It is a major exporter of shrimp. Other crops include coconuts, corn, rubber, soybeans, sugarcane and tapioca.[85]

Thailand is the world's third-largest seafood exporter. Overall fish exports were worth around US$3 billion in 2014, according to the Thai Frozen Foods Association. Thailand's fishing industry employs more than 300,000 persons.[86]

In 1985, Thailand designated 25 percent of its land area for forest protection and 15 percent for timber production. Forests have been set aside for conservation and recreation, and timber forests are available for the forestry industry. Between 1992 and 2001, exports of logs and sawn timber increased from 50,000 to 2,000,000 cubic meters per year.

The regional avian-flu outbreak contracted Thailand's agricultural sector in 2004, and the tsunami of 26 December devastated the Andaman Sea fishing industry. In 2005 and 2006, agricultural GDP was reported to have contracted by 10 percent.[87]

Thailand is the world's second-largest exporter of gypsum (after Canada), although government policy limits gypsum exports to support prices. In 2003 Thailand produced more than 40 different minerals, with an annual value of about US$740 million. In September 2003, to encourage foreign investment in mining the government relaxed its restrictions on mining by foreign companies and reduced mineral royalties owed to the state.[87]

Industry and manufacturing

[edit]

In 2007 industry contributed 43.9 percent of GDP, employing 14 percent of the workforce. Industry expanded at an average annual rate of 3.4 percent from 1995 to 2005. The most important sub-sector of industry is manufacturing, which accounted for 34.5 percent of GDP in 2004.

Electrical and electronics

[edit]Electrical and electronics (E&E) equipment is Thailand's largest export sector, amounting to about 15 percent of total exports. In 2014 Thailand's E&E exports totalled US$55 billion.[88]: 28 The E&E sector employed approximately 780,000 workers in 2015, representing 12.2 per cent of the total employment in manufacturing.[88]: 27

As of 2020[update], Thailand is the largest exporter of computers and computer components in ASEAN. Thailand is the world's second-biggest maker of hard disk drives (HDDs) after China, with Western Digital and Seagate Technology among the biggest producers.[89][90] But problems may loom for Thailand's high-tech sector. In January 2015, the country's manufacturing index fell for the 22nd consecutive month, with production of goods like televisions and radios down 38 percent year-on-year. Manufacturers are relocating to nations where labour is cheaper than Thailand. In April 2015, production will cease at an LG Electronics factory in Rayong Province.[91] Production is being moved to Vietnam, where labour costs per day are US$6.35 versus US$9.14 in Thailand. Samsung Electronics Co. Ltd. will site two large smartphone factories in Vietnam. It made around US$11 billion worth of investment pledges to the Vietnamese economy in 2014. As technologies evolve, e.g., as HDDs are replaced by solid-state drives (SSDs), manufacturers are reexamining where best to produce these latest technologies.[90] In addition, 74 percent of salaried workers in the sector face a high risk of being replaced by robots, as these positions consist of "repetitive, non-cognitive tasks".[88]: 39

Automotive

[edit]Thailand is the ASEAN leader in automotive production and sales. The sector employed approximately 417,000 workers in 2015, representing 6.5 per cent of total employment across all manufacturing industries and accounting for roughly 10 percent of the country's GDP. In 2014, Thailand exported US$25.8 billion in automotive goods.[88]: 12–13 As many as 73 percent of automotive sector workers in Thailand face a high risk of job loss due to automation.[88]: xix

| Year | Value (THB billion) | as % of GDP |

|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 566.355 | 5.37% |

| 2012 | 751.132 | 6.08% |

| 2013 | 812.085 | 6.29% |

| 2014 | 832.750 | 6.31% |

| 2015 | 892.623 | 6.53% |

| 2016 | 944.434 | 6.58% |

| 2017 | 881.380 | 5.90% |

| 2018 | 882.083 | n/a |

| Year | Units | Production for | Export value (THB billion) |

Export value as % of GDP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic | Export | ||||

| 2005 | 690,409 | 434,907 | 203.025 | 2.86% | |

| 2006 | 646,838 | 541,206 | 240.764 | 3.07% | |

| 2007 | 598,287 | 689,092 | 306.595 | 3.60% | |

| 2008 | 610,317 | 783,712 | 351.326 | 3.78% | |

| 2009 | 447,318 | 552,060 | 251.342 | 2.78% | |

| 2010 | 750,614 | 894,690 | 404.659 | 4.00% | |

| 2011 | 723,845 | 733,950 | 343.383 | 3.26% | |

| 2012 | 1,432,052 | 1,021,665 | 490.134 | 3.97% | |

| 2013 | 1,335,783 | 1,121,303 | 512.186 | 3.97% | |

| 2014 | 757,853 | 1,122,154 | 527.423 | 3.99% | |

| 2015 | 712,028 | 1,200,974 | 592.550 | 4.33% | |

| 2016 | 776,843 | 1,167,574 | 631.845 | 4.40% | |

| 2017 | 862,391 | 1,126,432 | 603.037 | 4.04% | |

| 2018 | 1,024,961 | 1,142,733 | 594.809 | n/a | |

| 2019 | 976,546 | 1,037,164 | 785.945 | n/a | |

| 2020 | 722,344 | 704,626 | 591.906 | n/a | |

| 2021 | 759,119 | 959,194 | 561.147 | n/a | |

| 2022 | 849,388 | 1,000,256 | 619.348 | 10.37% | |

| 2023 | 685,628 | 1,156,035 | 619.348 | 10.37% | |

Source: Federation of Thai Industries

Gems and jewelry

[edit]Gem and jewelry exports are Thailand's third-largest export category by value, trailing automotive and parts and computer components. In 2019, gem and jewelry exports, including gold, exceeded US$15.7 billion, up 30.3% from 2018 (486 billion baht, up 26.6%). Key export markets included ASEAN, India, the Middle East, and Hong Kong. The industry employs more than 700,000 workers according to the Gem and Jewelry Institute of Thailand (GIT).[92]

Energy

[edit]Thailand's 2004 energy consumption was estimated at 3.4 quadrillion British thermal units, representing about 0.7 percent of total world energy consumption. Thailand is a net importer of oil and natural gas; however, the government is promoting ethanol to reduce imports of petroleum and the gasoline additive methyl tertiary butyl ether.

In 2005 Thailand's daily oil consumption of 838,000 barrels per day (133,200 m3/d) exceeded its production of 306,000 barrels per day (48,700 m3/d). Thailand's four oil refineries have a combined capacity of 703,100 barrels per day (111,780 m3/d). The government is considering a regional oil-processing and transportation hub serving south-central China. In 2004, Thailand's natural-gas consumption of 1,055 billion cubic feet (2.99×1010 m3) exceeded its production of 790 billion cubic feet (2.2×1010 m3).

Thailand's 2004 estimated coal consumption of 30.4 million short tons exceeded its production of 22.1 million. As of January 2007, proven oil reserves totaled 290 million barrels (46,000,000 m3) and proven natural-gas reserves were 14.8 trillion cubic feet (420 km3). In 2003, recoverable coal reserves totalled 1,493 million short tons.[87]

In 2005, Thailand used about 118 billion kilowatt hours of electricity. Consumption rose by 4.7 percent in 2006, to 133 billion kWh. According to the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (the national electricity utility), power consumption by residential users is increasing due to more favorable rates for residential customers than for the industry and business sectors. Thailand's electric utility and petroleum companies (also state-controlled) are being restructured.

Services

[edit]In 2007 the service sector (which includes tourism, banking and finance), contributed 44.7 percent of GDP and employed 37 percent of the workforce.[87] Thailand's service industry is competitive, contributing to its export growth.[citation needed]

Banking and finance

[edit]Dangerous levels of non-performing assets at Thai banks helped trigger an attack on the baht by currency speculators which led to the Asian financial crisis in 1997–1998. By 2003, nonperforming assets had been cut in half (to about 30 percent).

Despite a return to profitability, Thailand's banks continue to struggle with unrealized losses and inadequate capital. The government is considering reforms, including an integrated financial regulatory agency which would enable the Bank of Thailand to focus on monetary policy. In addition, the government is attempting to strengthen the financial sector through the consolidation of commercial, state- and foreign-owned institutions. The 2004 Financial Sector Reform Master Plan provides tax breaks to financial institutions engaging in mergers and acquisitions. The reform program has been deemed successful by outside experts. In 2007 there were three state-owned commercial banks, five state-owned specialized banks, fifteen Thai commercial banks, and seventeen foreign banks in Thailand.[87]

The Bank of Thailand sought to stem the flow of foreign funds into the country in December 2006, leading to the largest one-day drop in stock prices on the Stock Exchange of Thailand since the 1997 Asian financial crisis. The sell-off by foreign investors amounted to more than US$708 million.[87]

In 2019, the Bank of Thailand kept its benchmark interest rate unchanged for a fourth straight meeting, with the concerns of high household debt and financial stability risks.[93]

Retail

[edit]Retail employs more than six million Thai workers. Most are employed by small businesses. Large multinational and national retail players (such as Tesco Lotus, 7-Eleven, Siam Makro, Big C, Villa Market, Central Group and Mall Group) are estimated to employ fewer than 400,000 workers. This accounts for less than seven percent of Thailand's total employment in retail.[88]: 70

Tourism

[edit]In 2016, tourism revenue, 2.53 trillion baht, accounted for 17.7 percent of Thailand's GDP, up from 16.7 percent in 2015. It is expected to generate 2.71 trillion baht in 2017. The global average for GDP contribution from tourism is nine percent.[94]

Cryptocurrencies

Thailand's Ministry of Finance approved four licensed brokers and dealers of cryptocurrencies in the country: Bx, Bitkub, Coins and Satang Pro. The country still did not elaborated regulation for ICOs, though it announced in late 2018 to loosen the rules.[95]

Labour

[edit]Thailand's labour force has been estimated at from 36.8 million employed (of 55.6 million adults of working age)[96] to 38.3 million (1Q2016).[97] About 49 percent were employed in agriculture, 37 percent in the service sector and 14 percent in industry. In 2005 women constituted 48 percent of the labour force, and held an increased share of professional jobs. Thailand's unemployment rate was 0.9 percent as of 2014, down from two percent in 2004.[37] A World Bank survey showed that 83.5 percent of the Thai workforce is unskilled.[96]

A joint study by the Quality Learning Foundation (QLF), Dhurakij Pundit University (DPU), and the World Bank suggests that 12 million Thais may lose their jobs to automation over the next 20 years, wiping out one-third of the positions in the workforce.[96] The World Bank estimates that Thai workers are two times and five times less productive than Malaysian and Singaporean workers respectively. The report assesses the average output of Thai workers at US$25,000 (879,200 baht) in 2014 compared to Malaysia's US$50,000 and US$122,000 for Singapore.[96] A 2016 report by the International Labor Office (ILO) estimates that over 70 percent of Thai workers are in danger of being displaced by automation.[88]: xviii Factories in Thailand are estimated to be adding from 2,500–4,500 industrial robots per year.[98]: 18

In fiscal year 2015, 71,000 Thais worked abroad in foreign countries. Taiwan employed the most Thai employees overall with 59,220 persons, followed by South Korea at 24,228, Israel at 23,479, Singapore at 20,000, and the UAE at 14,000. Most employees work in metal production, agriculture, textile manufacturing, and electronic part manufacturing fields.[99] As of 2020, Thai migrant labourers overseas generate remittances worth 140 billion baht.[100]

The number of migrant workers in Thailand is unknown. The official number—1,339,834 registered migrant workers from Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar—reported by the Office of Foreign Workers Administration under the Ministry of Labour, represents only legal migrant workers. Many more are presumed to be non-registered or illegal migrants. The Thailand Development Research Institute (TDRI) estimates that there may yet be more illegal migrant workers than legal ones in Thailand.[101]

Foreign trade

[edit]

China has replaced the United States as Thailand's largest export market while the latter still holds its position as its second-largest supplier (after Japan). While Thailand's traditional major markets have been North America, Japan, and Europe, economic recovery in Thailand's regional trading partners has helped Thai export growth.

As of 2022, China is Thailand's largest trading partner with 3.69 trillion baht ($106 billion) worth of trade, accounting for almost 20% of all Thai foreign trade. In 2022, China also became the largest foreign investor in Thailand, totaling 77.4 billion baht, more than Japan and USA.[102]

Recovery from financial crisis depended heavily on increased exports to the rest of Asia and the United States. Since 2005 the increase in export of automobiles from Japanese manufacturers (particularly Toyota, Nissan and Isuzu) has helped improve the trade balance, with over one million cars produced annually since then. Thailand has joined the ranks of the world's top ten automobile-exporting nations.[103]

Machinery and parts, vehicles, integrated circuits, chemicals, crude oil, fuels, iron and steel are among Thailand's principal imports. The increase in imports reflects a need to fuel production of high-tech items and vehicles.

Thailand is a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO), the Cairns Group of agricultural exporters and the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA), and has pursued free-trade agreements. A China-Thailand Free Trade Agreement (FTA) began in October 2003. This agreement was limited to agricultural products, with a more comprehensive FTA planned to be signed by 2010. Thailand also has a limited free-trade agreement with India (since 2003) and a comprehensive Australia-Thailand Free Trade Agreement, which began on 1 January 2005.

Thailand began free trade negotiations with Japan in February 2004, and an in-principle agreement was agreed to in September 2005. Negotiations for a US-Thailand free trade agreement have been underway, with a fifth round of meetings held in November 2005.

Several industries are restricted to foreign investment by the 1999 Foreign Business Act. These industries include media, agriculture, distribution of land, professional services, tourism, hotels, and construction. Share ownership of companies engaged in these activities must be limited to a 49 percent minority stake. The 1966 US-Thailand Treaty of Amity and Economic Relations provides exemption of these restrictions for shareholders with United States citizenship.[104]

The Bangkok area is one of the most prosperous parts of Thailand and heavily dominates the national economy, with the infertile northeast being the poorest. A concern of successive Thai governments, and a focus of the recently ousted Thaksin government, has been to reduce the regional disparities which have been exacerbated by rapid economic growth in Bangkok and financial crisis.

Although little economic investment reaches other parts of the country except for tourist zones, the government has stimulated provincial economic growth in the eastern seaboard and the Chiang Mai area. Despite talk of other regional development, these three regions and other tourist zones still dominate the national economy.

Although some US rights holders report good cooperation with Thai enforcement authorities (including the Royal Thai Police and Royal Thai Customs), Thailand remained on the priority watch list in 2012. The United States is encouraged that Thailand's government has affirmed its commitment to improving IPR protection and enforcement, but more must be done for Thailand to be removed from the list.[105]

Although the economy has grown moderately since 1999, future performance depends on continued reform of the financial sector, corporate-debt restructuring, attracting foreign investment and increasing exports. Telecommunications, roads, electricity generation and ports showed increasing strain during the period of sustained economic growth. Thailand is experiencing a growing shortage of engineers and skilled technical personnel.

Major Trade Partners

[edit]The following table shows the largest trading partners for Thailand in 2021 by total trade value in billions of USD.[106]

| Country | Total Trade Value | Import Value | Export Value | Balance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 128.24 | 66.43 | 61.82 | -4.61 | |

| 65 | 14.58 | 50.43 | 35.85 | |

| 61.92 | 35.57 | 26.35 | -9.22 | |

| 23.05 | 12.05 | 11 | -1.05 | |

| 17.99 | 6.42 | 11.57 | 5.15 | |

| 17.37 | 8.22 | 9.15 | 0.93 | |

| 17.15 | 7.34 | 9.81 | 2.46 | |

| 16.9 | 9.9 | 7.01 | -2.89 | |

| 16.51 | 2.84 | 13.67 | 10.84 | |

| 15.08 | 6.41 | 8.67 | 2.26 |

Regional economies

[edit]Isan

[edit]The economy of Isan is dominated by agriculture, although output is poor and this sector is decreasing in importance at the expense of trade and the service sector. Most of the population is poor and badly educated. Many labourers have been driven by poverty to seek work in other parts of Thailand or abroad.

Although Isan accounts for around a third of Thailand's population and a third of its area, it produces only 8.9 percent of GDP. Its economy grew at 6.2 percent per annum during the 1990s.

In 1995, 28 percent of the population was classed as below the poverty line, compared to just 7 percent in central Thailand. In 2000, per capita income was 26,317 baht, compared to 208,434 in Bangkok. Even within Isan, there is a rural/urban divide. In 1995, all of Thailand's ten poorest provinces were in Isan, the poorest being Sisaket. However, most wealth and investment is concentrated in the four major cities of Khorat, Ubon, Udon, and Khon Kaen. These four provinces account for 40 percent of the region's population.

Special Economic Zones (SEZ)

[edit]In his televised national address on 23 January 2015 in the program "Return Happiness to the People", Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha addressed the government's policy on the establishment of special economic zones.[107]

He said that the policy would promote connectivity and regional economic development on a sustainable basis. There are currently 10 SEZs in Thailand, with trade and investment valued at almost 800 billion baht a year.

In 2014, the government launched a pilot project to set up six special economic zones in five provinces: Tak, Mukdahan, Sa Kaeo, Songkhla, and Trat. In the second phase, which is expected to begin in 2016, seven special economic zones will be established in another five provinces: Chiang Rai, Kanchanaburi, Nong Khai, Nakhon Phanom, and Narathiwat.[107]

In early 2015, the government approved an infrastructure development plan in special economic zones. In 2015, the plan includes 45 projects, budgeted at 2.6 billion baht. Another 79 projects, worth 7.9 billion baht, will be carried out in 2016. Relying on a mix of government revenue, bond sales, and other funding, Prayut plans to spend US$83 billion over seven years on new railways, roads, and customs posts to establish cross-border trade routes. The idea is to link some 2.4 billion consumers in China and India with Asia's newest economic grouping, the ASEAN Economic Community, of which Thailand is a member.[108]

Critics of the SEZs maintain that free trade agreements and SEZs are incompatible with the principles of the late-King Bhumibol's sufficiency economy,[109] claimed by the government to be the inspiration for governmental economic and social policies.[110]

Shadow economy

[edit]"Thailand's shadow economy ranks globally among the highest," according to Friedrich Schneider, an economist at Johannes Kepler University of Linz in Austria, author of Hiding in the Shadows: The Growth of the Underground Economy.[111] He estimates Thailand's shadow economy was 40.9 percent of real GDP in 2014, including gambling and small weapons, but largely excluding drugs.[112] Schneider defines the "shadow economy" as including all market-based legal production of goods and services that are deliberately concealed from public authorities for the following reasons: (1) to avoid payment of income, value added or other taxes, (2) to avoid payment of social security contributions, (3) to avoid having to meet certain legal labor market standards, such as minimum wages, maximum working hours, or safety standards, and (4) to avoid complying with certain administrative procedures, such as completing statistical questionnaires or other administrative forms. It does not deal with typical underground, economic (classical crime) activities, which are all illegal actions that fits the characteristics of classical crimes like burglary, robbery, or drug dealing.[113] The shadow economy also includes loan sharking. According to estimates, there are about 200,000 "informal lenders" in the country, many of whom charge exorbitant interest rates, creating an often insurmountable burden for low-income borrowers.[114]

See also

[edit]- Stock Exchange of Thailand

- Foreign aid to Thailand

- Thailand and the International Monetary Fund

- List of Thai provinces by GPP

Further reading

[edit]- The economic history of Siam from the 16th to the 19th century, together with factors affecting the economic outlook for the twentieth, are presented in Wright, Arnold; et al. (2008) [1908]. Wright, Arnold; Breakspear, Oliver T (eds.). Twentieth century impressions of Siam (PDF). London: Lloyds Greater Britain Publishing Company. Retrieved 7 October 2011.

- Porphant Ouyyanont. 2017. A Regional Economic History of Thailand. ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute.

- Pasuk Phongpaichit and Chris Baker. “A History of Thailand”. Cambridge University Press.

- Pasuk Phongpaichit and Chris Baker. “A History of Ayutthaya.”

- Sompop Manarungsan. “Economic Development of Thailand: 1850-1950”

- David Feeny. “Political Economy of Productivity”

- Tomas Larsson. “Land and Loyalty.”

- James Ingram. “Economic Change in Thailand: 1850-1970.”

- William Skinner. “Chinese Society in Thailand: An Analytical History.” Cornell University Press

- Jessica Vechbanyongratana and Thanyaporn Chankrajang: “A Brief Economic History of Land Rights in Thailand.”

- Panarat Anamwathana and Jessica Vechbanyongratana. 2021. "The economic history of Thailand: Old debates, recent advances, and future prospects."

- Suehiro, Akira (1996). Capital Accumulation in Thailand 1855-1985. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books. ISBN 9789743900051. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Hewison, Kevin (1989). Bankers and Bureaucrats Capital and the Role of the State in Thailand (PDF). New Haven: Yale University Southeast Asia Studies. ISBN 0-938692-41-0. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

References

[edit]- ^ "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2019". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ "World Bank Country and Lending Groups". datahelpdesk.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ "Population, total". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ a b c d "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2024". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 24 November 2024.

- ^ a b c "WORLD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK 2022 OCT Countering the Cost-of-Living Crisis". www.imf.org. International Monetary Fund. p. 43. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ a b "Thailand at a glance". Bank of Thailand. Archived from the original on 27 March 2013. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ "Poverty headcount ratio at national poverty lines (% of population) - Thailand". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ "Poverty headcount ratio at $5.50 a day (2011 PPP) (% of population) – Thailand". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ "GINI index (World Bank estimate)". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ a b "Human Development Report 2023/2024" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 13 March 2024. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 March 2024. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- ^ "Labor force, total - Thailand". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ "Employment to population ratio, 15+, total (%) (national estimate) - Thailand". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2020". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d "การค้าระหว่างประเทศของไทย กับ โลก". Ministry of Commerce. 2023. Archived from the original on 5 July 2020. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- ^ "COUNTRY COMPARISON :: STOCK OF DIRECT FOREIGN INVESTMENT – AT HOME". The World Factbook. Archived from the original on 11 December 2007. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- ^ "External debt (US$)". Archived from the original on 2 July 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ^ "Public debt outstanding". Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ Government’s Net Revenue Collection: Fiscal Year 2023 (October 2022 - September 2023) Royal Thai Government.

- ^ Disbursement summary as of 4th quarter of fiscal year 2023 Parliamentary Budget Office.

- ^ "Sovereigns rating list". Standard & Poor's. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- ^ a b Rogers, Simon; Sedghi, Ami (15 April 2011). "How Fitch, Moody's and S&P rate each country's credit rating". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- ^ "Fitch Upgrades Thailand to 'BBB+'; Outlook Stable". FitchRatings. Archived from the original on 13 March 2014. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ https://www.jcr.co.jp/download/f6626688e6d6bf4e6e654d6de4254ff53f49de2596e638d6e6/17i0003_f.pdf Archived 29 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "International Reserves". Bank of Thailand. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ "Exports of goods and services (% of GDP) - Thailand | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ a b International Monetary Fund. "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2024". International Monetary Fund.

- ^ "Change in Price Level" (PDF). Bank of Thailand. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 October 2008. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ "Thai Economic Performance in Q4 and 2012 and Outlook for 2013" (PDF). Office of the Economic and Social Development Board. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 March 2014. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ^ RMB role and share of international payments is declining CTMfile. 5 April 2017

- ^ Thailand's Annual Infrastructure Report 2008 (PDF). Washington DC: World Bank. 1 January 2008. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ "International Reserves (Weekly)". Bank of Thailand. Archived from the original on 28 June 2018. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- ^ "COUNTRY COMPARISON : CURRENT ACCOUNT BALANCE". The World Factbook. Archived from the original on 13 June 2007. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ^ "World Trade Developments" (PDF). World Trade Organization. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ "Thailand". World Bank. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ^ "GNI per capita, Atlas method (current US$)". Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- ^ "ตารางที่ 1.2 สัดส่วนคนจน เมื่อวัดด้านรายจ่ายเพื่อการอุปโภคบริโภค จำแนกตามภาคและพื้นที่ ปี พ.ศ. 2531–2559". Office of the National Economic and Social Development Board. Archived from the original on 25 April 2018. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- ^ a b [1] Archived 12 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine TNSO The National Statistical Office of Thailand. "Over half of all Thailand's workers are in vulnerable employment (defined as the sum of own-account work and unpaid family work) and more than 60 percent are informally employed, with no access to any social security mechanisms". Thailand. A labour market profile, International Labour Organization, 2013.

- ^ Tanakasempipat, Patpicha (27 January 2017). "Thailand to spend $5.4 bln more to boost growth in provinces". Reuters. Retrieved 22 April 2024.

Thailand's original budget for the 2017 fiscal year, which started in October and lasts until September this year, was 2.73 trillion baht ($77.40 billion).

- ^ "Rehab plans for state agencies backed". The Nation. 29 May 2018. Archived from the original on 16 June 2019. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- ^ de Lapomarede, Baron (September 1934). "The Setting of the Siamese Revolution". Pacific Affairs. 7 (3). University of British Columbia Press: 251–259. doi:10.2307/2750737. JSTOR 2750737.

- ^ Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 293. ISBN 9781107507180.

- ^ a b Nilnopkoon, Somsak. "Abstract" (PDF). The Thai Economic Problems After the Second World War and the Government Strategies in Dealing with Them. Silpakorn University. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- ^ a b c สถิตนิรามัย, อภิชาต. "การเมืองของการพัฒนาเศรษฐกิจยุคแรก 2498–2506". Archived from the original on 12 May 2012. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- ^ "The National Economic and Social Development Plan". Office of the National Economic and Social Development Board. Archived from the original on 26 August 2012. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- ^ Unger, Danny (1998). Building Social Capital in Thailand: Fibers, Finance and Infrastructure. Cambridge University Press. p. 61. ISBN 9780521639316.

- ^ "Asia After Viet Nam". Foreign Relations of the United States (FRUS), 1969–1976, Volume 1, Document 3. U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ^ "พัฒนาการของเศรษฐกิจไทย". Siam Intelligence. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- ^ Yu, Tzong-Shian (30 August 2001). From Crisis to Recovery: East Asia Rising Again?. World Scientific Publishing. p. 267. ISBN 9789814492300. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- ^ หมวกพิมาย, อดิศร. "การเมืองเรื่องลดค่าเงินบาทสมัยพลเอกเปรม ติณสูลานนท์". ฐานข้อมูลการเมืองการปกครอง สถาบันพระปกเกล้า. Archived from the original on 26 September 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Thailand". World Economic Outlook Database, Apr 2012. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ^ a b c Chutipat, Weraphong. "วิกฤตการณ์ต้มยำกุ้ง ตอน "6 สาเหตุ ที่ทำให้….. ประเทศไทยเข้าสู่..วิกฤต !!"". Archived from the original on 3 June 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ^ "How the baht was 'attacked'". Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ^ ""ดร.โกร่ง" กุนซือเศรษฐกิจ 7 สมัย 7นายกฯ กับชีวิตเรือนน้อยในป่าใหญ่". Matichon Online. Archived from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ^ "โล่งแผนคุมบาทไม่เอี่ยวกระทบหุ้น SET ติดปีก ดัชนีดีดบวก 14 จุด". Manager Online. Archived from the original on 1 November 2012. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- ^ "Thailand". World Economic Outlook Database. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- ^ "Recovery from the Asian Crisis and the Role of the IMF". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- ^ Aidan Jones (31 January 2014). "Thai northeast vows poll payback to Shinawatra clan". AFP. Retrieved 8 February 2014.[dead link]

- ^ a b c d "Thailand Competitiveness Conference 2011". Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- ^ a b c d e "Quarterly Gross Domestic Product". Office of the National Economic and Social Development Board. Archived from the original on 1 February 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ^ Withitwinyuchon, Nutthathirataa. "Thailand's political conflict deemed to continue after election". xinhuanet. Archived from the original on 19 January 2011. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- ^ Phisanu Phromchanya (24 February 2012). "Thailand Economy To Rebound Strongly In 2012". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- ^ "The World Bank Supports Thailand's Post-Floods Recovery Effort". The World Bank. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- ^ "Gross Domestic Product: Q2/2012" (PDF). Office of the National Economic and Social Development Board. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 September 2012. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- ^ "IMD announces its 2012 World Competitiveness Rankings". IMD. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- ^ "Thailand: Gross domestic product, current prices". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ^ Justina Lee (23 December 2013). "Baht Falls to a Three-Year Low, Stocks Drop on Political Unrest". Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- ^ "Cambodian exodus from Thailand jumps to nearly 180,000". AFP. AFP. 17 June 2014. Archived from the original on 17 June 2014. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ "Confidence in Thailand boosted after curfew lifted: FTI". The Nation. 16 June 2014. Archived from the original on 11 August 2014. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ Pesek, William (4 December 2015). "Thailand's Generals Shoot Economy in the Foot". Barron's. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ Fuller, Thomas (29 November 2015). "Thai Economy and Spirits Are Sagging". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ^ "Bank of Thailand holds key rate as growth weakens, baht surges". Business Times. 26 June 2019. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- ^ a b c d Phoonphongphiphat, Apornrath (2 January 2017). "Thailand 4.0: Are we ready?". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ Languepin, Olivier (15 September 2016). "Thailand 4.0, what do you need to know?". Thailand Business News. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ "ธ.โลกประเมินเศรษฐกิจไทยปีนี้ ถดถอยมากที่สุดในภูมิภาคอาเซียน". BBC ไทย (in Thai). 29 September 2020. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ Sriring, Orathai; Ghoshal, Devjyot (15 August 2024). "Political turmoil threatens prospects of Thailand's floundering economy". Reuters. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

- ^ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects".

- ^ Arunmas, Phusadee (31 May 2016). "Businesses downbeat on prospects". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- ^ Theparat, Chatrudee (3 December 2016). "Number of poor Thais shrinks". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ^ Global Wealth Report 2016. Zurich: Credit Suisse AG. November 2016. Archived from the original on 15 May 2017. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ Wangkiat, Paritta (30 June 2017). "Sino rail deal nothing to be proud about". Editorial. Bangkok Post. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ Global Wealth Databook 2016 (PDF). Zurich: Credit Suisse AG. November 2016. p. 148. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 April 2018. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ Getting Back on Track; Reviving Growth and Securing Prosperity for All; Thailand Systematic Country Diagnostic (PDF). Washington: World Bank Group. 7 November 2016.

- ^ a b c d Henri Leturque and Steve Wiggins 2010.Thailand's progress in agriculture: Transition and sustained productivity growth Archived 27 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine. London: Overseas Development Institute

- ^ International Grains Council. "Grain Market Report (GMR444)", London, 14 May 2014. Retrieved on 13 June 2014.

- ^ Mydans, Seth (18 July 2010). "Wasps to Fight Thai Cassava Plague". The New York Times.

- ^ Lefevre, Amy Sawitta; Thepgumpanat, Panarat. "Thai fishermen strike over new rules imposed after EU's warning". Reuters. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Thailand country profile. Library of Congress Federal Research Division (July 2007). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c d e f g Chang, Jae-Hee; Rynhart, Gary; Huynh, Phu (July 2016). ASEAN in transformation: How technology is changing jobs and enterprises (PDF) (Bureau for Employers' Activities (ACT/EMP) working paper; No. 10 ed.). Geneva: International Labour Office, Bureau for Employers' Activities (ACT/EMP). ISBN 978-92-2-131142-3. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- ^ "Thailand No 1 exporter of computers, components in Asean". The Star. Malaysia. 19 May 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ^ a b Sriring, Orathai; Temphairojana, Pairat (18 March 2015). "Thailand's outdated tech sector casts cloud over economy". Reuters US. Reuters. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ^ "LG Electronics to move Thailand TV production to Vietnam". Reuters. 17 March 2015. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ^ Phusadee, Arunmas (15 May 2020). "Jewellery makers seek government lifeline". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ "Bank of Thailand Holds Key Rate as It Warns of Currency's Gains". Bloomberg. Bloomberg L.P. 26 June 2019. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- ^ Theparat, Chatrudee (17 February 2017). "Tourism to continue growth spurt in 2017". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- ^ "Thailand issues its first licenses to 4 crypto exchanges". TechCrunch. 9 January 2019. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d Dumrongkiat, Mala (13 July 2016). "Technology 'imperils 12 million jobs'". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ "Economic and Social News; Thailand's Social Development in Q1/2016" (PDF). Office of the National Economic and Social Development Board. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 June 2016. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- ^ "World Robotics 2016; Executive Summary World Robotics 2016 Industrial Robots" (PDF). International Federation of Robotics. Frankfurt. 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- ^ Sangiam, Tanakorn; Gershon, Joel. "71,000 Thais employed abroad in 2015". NNT. National News Bureau of Thailand (NNT). Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ^ Charoensuthipan, Penchan (21 June 2020). "Thousands of Thai workers to return to Taiwan". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- ^ Chalamwong, Yongyuth; Chaladsook, Alongkorn (27 July 2016). "End Thailand's relaxed labour laws". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ^ "Thailand hosts giant China business convention to lure FDI".

- ^ "Country Profile: Thailand". InvestAsian. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ Thailand Company Formation Healy Consultants 3 September 2013

- ^ "US Keeps Thailand In Piracy List, But Focus On China". Archived from the original on 9 May 2012.

- ^ "Thailand - Trading Partners and Trade Balances 2021". maxinomics.com. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ a b "Special Economic Zones". Royal Thai Government. Archived from the original on 4 December 2015. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ^ Mellor, William (9 November 2015). "Taming Thailand's Wild Frontier". Bloomberg Markets. Bloomberg Business. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ^ Chanyapate, Chanida; Bamford, Alec (n.d.). "The Rise and Fall of the Sufficiency Economy". Focus on the Global South. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ Sufficiency Economy Philosophy: Thailand's Path towards Sustainable Development Goals (PDF). Bangkok: Ministry of Foreign Affairs. n.d. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ Schneider, Friedrich; Enste, Dominik (March 2003). Hiding in the Shadows: The Growth of the Underground Economy (Economic Issues No. 30 ed.). International Monetary Fund (IMF). Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ^ Blake, Chris (1 July 2015). "Bangkok's Sex Shops, Street Bars Survive Graft Crackdown". BloombergBusiness. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- ^ Schneider, Friedrich (December 2004). The Size of the Shadow Economies of 145 Countries all over the World: First Results over the Period 1999 to 2003 (PDF). Bonn, Germany: Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit (IZA). Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- ^ "PM wants pico-finance operators nationwide". The Nation. 2 March 2017. Archived from the original on 23 October 2017. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

External links

[edit]- Thai Ministry of Commerce

- Thailand Business News

- World Bank Summary Trade Statistics Thailand

- Tariffs applied by Thailand as provided by ITC's ITC Market Access Map, an online database of customs tariffs and market requirements