Beizi

| Beizi | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

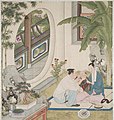

Ming dynasty portrait of man wearing a "Ming Styled" beizi over zhiduo | |||||||

| Chinese | 褙子 | ||||||

| |||||||

Beizi (Chinese: 褙子; pinyin: bèizi), also known as beizi (Chinese: 背子; pinyin: bēizi)[1][2] and chuozi (Chinese: 綽子; pinyin: chuòzi),[3] is an item worn in traditional Chinese attire common to both men and women;[3] it is typically a large loose outer coat with loose and long sleeves.[4][5] It was most popular during the Song dynasty, Ming dynasty, and from the early Qing to the Mid-Qing dynasty. The beizi originated in the Song dynasty.[3][5][6] In the Ming dynasty, the beizi was referred as pifeng (Chinese: 披風; pinyin: pī fēng).[7] When worn by men, it is sometimes referred as changyi (Chinese: 氅衣), hechang (Chinese: 鹤氅; pinyin: hèchǎng; lit. 'crane cloak'), or dachang (Chinese: 大氅) when it features large sleeves and knotted ties at the front as a garment closure.[8]

Terminology

[edit]Beizi (背子) literally means "person sitting behind".[2] According to Zhu Xi, the beizi may have originally been clothing worn by concubines and maidservants, and it was then named after these people as they would always walk behind their mistress.[5]

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]The beizi originated in the Song dynasty;[5][6] it is assumed that it was derived from the banbi, where the sleeves and the garment lengthened.[9][10] According to Ye Mende, the beizi was initially worn as a military clothing with "half-sleeves"; the sleeves were later extended and hanging ribbons were added from the armpits and back.[5] In earlier times, the beizi did not exist according to both Zhu Xi and Lu You, and it only became popular by the Late Northern Song dynasty.[5]

Song dynasty

[edit]In the Song dynasty, the beizi was worn by all social strata regardless of gender; however, it was a more prevalent in people of the higher social status.[4][5] Emperor Zhezong and Emperor Huizong both wore yellow beizi while the Grand Councillors of the Northern Song period would wear purple beizi with a round collar; this form of fashion remained until the Xuanhe period.[5]

The beizi had a straight silhouette, and the Song dynasty people liked its elegance which reflect the cultural and psychological development of the Song dynasty people who liked simplicity.[4] Zhu Xi also created some rules for dressing, which included the wearing of beizi by unmarried women and concubines.[11] While women were prescribed to wear beizi as a regular dress, men could only wear it in informal situation.[3] The male Song dynasty beizi was worn as informal clothing at home because it could be left unfastened in the front, because of the relaxed waistline and as the beizi could come in variety of length and width.[4] Examples of beizi artefacts worn by women dating from Song dynasty were unearthed from the tomb of Huang Sheng.[12]

During the Song dynasty, the hechang (Chinese: 鶴氅; pinyin: hèchǎng; lit. 'crane cloak') was worn as a casual form of clothing by the recluse and retired officials; it could be worn over a zhiduo.[13] Hechang was long and loose, and it could be made of down of crane and other birds, it was long enough for its lower hem to reach the ground.[14]

-

Unearthed beizi with narrow sleeves from the tomb of Huang Sheng, Southern Song dynasty.

-

Commoner women wearing beizi, Song dynasty.

-

Song dynasty women wearing beizi (褙子), Northern Song dynasty (960–1127 AD).

-

Song dynasty relief of a woman wearing a beizi.

-

Women wearing beizi, Song dynasty Tomb Painting Found in Tengfeng City.

-

Court Ladies of the Former Shu wearing post-Tang Style beizi.

-

Song dynasty beizi, 12th century.

-

A man wearing a "Song Style" beizi, or hechang (鶴氅).

-

A man wearing a hechang.

-

Portrait of Bi Shichang wearing hechang.

Ming dynasty

[edit]In the Ming dynasty, the women's pifeng became so long by the 16th century that it caused some anxieties to government officials as the women's pifeng started to look closer to the men's clothing; i.e. traditionally, woman's upper garment had to be levelled at her waist with a lower garment which meets the upper garment in order to represent "earth supports heaven".[7] In the Ming dynasty, when the pifeng came to be lengthened to the point that woman's upper garment covered the lower skirts; it was perceived as a confusion between man and woman as it was men who traditionally had their upper garments covering their lower garments to symbolize "heaven embraces earth".[7]

The pifeng was a prominent clothing for women in the late ming dynasty as a daily dress in the 16th and 17th century.[7]

-

Ming dynasty portrait of a Woman wearing a "Ming Styled" beizi (also known as pifeng).

-

Ming dynasty portrait of a man wearing a "Ming Styled" beizi.

-

Men wearing beizi, Ming dynasty, 16th century

-

A Ming Portrait of a man wearing "Ming styled" Beizi

Qing dynasty

[edit]During the Qing dynasty, the Ming-style form of clothing remained dominant for Han Chinese women; this included the beizi among various forms of clothing.[15] In the 17th and 18th century AD, the beizi (褙子) was one of the most common clothing and fashion worn by women in Qing dynasty, along with the ruqun, yunjian, taozi and bijia.[16] The pifeng continued to be worn even after the fall of the Qing dynasty, but eventually disappeared by the 19th century.[7]

-

Qing dynasty beizi, illustration d. before 1732 AD

-

Qing dynasty beizi, illustration d. before 1732 AD

-

Qing dynasty beizi, illustration d. before 1732 AD

-

Woman wearing beizi, Domestic Scene from an Opulent Household, Qianlong period.

-

Woman wearing beizi, Qing dynasty.

-

Beizi, from the 18th century novel Dream of the Red Chamber.

21st century: Modern beizi and pifeng

[edit]The beizi and pifeng which are based on various dynasties regained popularity in the 21st century with the emergence of the Hanfu Movement and were modernized or improved.[17][18]

-

Modern pink pifeng.

Construction and design

[edit]The beizi has a straight silhouette with vents and seams at the sides.[6][4] It has a parallel/straight-collar (Chinese: 對襟; pinyin: duijin);[19] i.e. there is a pair of disconnected foreparts which were parallel to each other.[5] The beizi could also be found with side slits which could start at beginning at the armpit down its length or without any side slits at all.[4][5] In the song dynasty, the beizi was not fastened so that the inner clothing could be exposed.[6][4] The beizi also came in variety of length, i.e. above knees, below knees, and ankle length, and the sleeves could vary in size (i.e. either narrow or broad).[4]

In the Song dynasty, other styles of beizi were also found in addition to the aforementioned style:

- There is a style of beizi wherein ribbons could be hung from both the armpits and the back, with a silk belt which fastened the front and back of the beizi together, or the front and back parts of the beizi could also be left unbound.[5] According to Cheng Dachang, the use of ribbons under the armpits was assumed to have been a way to imitate the crossing ribbons of earlier ancient Chinese clothing in order to maintain the clothing of the ancient times.[5]

- A "half-beizi", a beizi with short sleeves; it was originally worn as a military uniform but it was then worn by the literati and the commoners despite being against the Song dynasty's dressing etiquette.[5]

- A "sleeveless beizi", which looks like a modern sleeveless vest, was used as a casual clothing and could be found in the market.[5] They were made of ramie or raw silk fabric.[5]

The beizi also developed with time. The earlier Song dynasty beizi had a band which finished the edges down to the bottom hem, but with time, it developed further and a contrasting neckband which encircled the neck down to the mid-chest; a closing was also found at the mid-chest.[6][20] In the Song dynasty, the sleeves of the beizi was fuller, but it became more tubular in shape in the Ming dynasty.[6]

By the late Ming dynasty, the beizi (also known as pifeng) had become longer and almost covered the skirts completely which came to look almost like the men's clothing and the sleeves grew larger trailing well below the finger tips.[7] The neckband, however, was shortened to reach mid-chest and the robe was made wider.[20] In the Ming dynasty, beizi can be secured at the front either with a metal or jade clasp button called zimu kou (Chinese: 子母扣).[21]

Gender differences

[edit]The gender difference is that while wide-sleeved beizi were considered formal wear for women (narrow-sleeved beizi were casual wear for women), both wide and narrow-sleeved beizi were only used as casual wear for men.[citation needed]

Depictions and media

[edit]- In the Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Zhuge Liang is said to be wearing hechang.[22]: 56

-

Zhu Geliang wearing a hechang (also known as beizi).

Influences and derivatives

[edit]China

[edit]In Chinese opera, costumes such as nüpi (Chinese: 女帔; a form of women's formal attire) and pi (Chinese: 帔; a form of men's formal attire) were derived from the beizi worn during the Ming dynasty (i.e. pifeng).[23][24] Both pi and nüpi had tubular sleeves which were longer than then wrist length.[23] Water sleeves were also added to the sleeves for both pi and nüpi; the water sleeves worn with the nüpi are longer than those worn with the pi.[23] The nüpi had straight sides and vents and was knee length; the length of the nüpi was historically accurate.[23] The pi had a flared side seams with vents and was ankle-length.[23] It could be closed with a single Chinese frog button or with a fabric tie.

-

Qing dynasty period pi costume (front view).

-

Qing dynasty period pi costume (back view).

Korea

[edit]The hechang (known as hakchang in Korea) was introduced during the 17th and 18th century in Joseon by people who had exchanges with Chinese or liked Chinese classic styles and gradually became popular among the Joseon people; Joseon scholars started to borrow the looks of Zhuge Liang due to the popularity of the Romance of the Three Kingdoms; and thus, the hakchangui was increasingly worn by more and more Joseon scholars.[25] In Joseon, fans with white feather and the hakchangui became the representative clothing of Zhuge Liang, hermits, and scholars who followed taoism.[26]

Vietnam

[edit]The Ao Nhat Binh (chữ Nôm: 襖日平, Vietnamese: Áo Nhật Bình, lit. 'rectangle-collared garb'), which was a casual outer garment worn by the female royal family, female officials, and high noble ladies of the Nguyen dynasty during informal occasions, originated from the Ming dynasty pifeng (Vietnamese: Áo Phi Phong) which was popular in China.[27][28] The Ao Nhat Binh was further developed in the Nguyen dynasty to denote social ranking of women through the use of colours and embroidery patterns.[29]

-

Vietnamese woman wearing Áo Nhật Bình

Similar items

[edit]- Daxiushan

- Daopao in the form of hechang (crane cloak) - a form of Taoist clothing

Related items

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Zhongguo gu dai ming wu da dian. Fu Hua, 華夫. (Di 1 ban ed.). Jinan Shi: Jinan chu ban she. 1993. p. 567. ISBN 7-80572-575-6. OCLC 30903809.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b Zang, Yingchun; 臧迎春. (2003). Zhongguo chuan tong fu shi. 李竹润., 王德华., 顾映晨. (Di 1 ban ed.). Beijing: Wu zhou chuan bo chu ban she. ISBN 7-5085-0279-5. OCLC 55895164.

- ^ a b c d Yuan, Zujie (2007). "Dressing for power: Rite, costume, and state authority in Ming Dynasty China". Frontiers of History in China. 2 (2): 181–212. doi:10.1007/s11462-007-0012-x. ISSN 1673-3401. S2CID 195069294.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hua, Mei; 华梅 (2004). Zhongguo fu shi (Di 1 ban ed.). Beijing: Wu zhou chuan bo chu ban she. pp. 50–52. ISBN 7-5085-0540-9. OCLC 60568032.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Zhu, Ruixi; 朱瑞熙 (2016). A social history of middle-period China : the Song, Liao, Western Xia and Jin dynasties. Bangwei Zhang, Fusheng Liu, Chongbang Cai, Zengyu Wang, Peter Ditmanson, Bang Qian Zhu (Updated ed.). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-1-107-16786-5. OCLC 953576345.

- ^ a b c d e f B. Bonds, Alexandra (2008). Beijing Opera Costumes: The Visual Communication of Character and Culture. University of Hawaii Press. p. 53. ISBN 9780824829568.

- ^ a b c d e f Finnane, Antonia (2008). Changing clothes in China : fashion, history, nation. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 50–52. ISBN 978-0-231-14350-9. OCLC 84903948.

- ^ "Traditional Chinese Winter Clothing for Male - Changyi". www.newhanfu.com. 16 December 2020. Retrieved 2021-06-24.

- ^ 朱和平 (July 2001). 《中国服饰史稿》 (PDF) (in Chinese) (1st ed.). 中州古籍出版社. pp. 223–224. Retrieved May 20, 2009.

- ^ 梅·華 (2011). Chinese Clothing. Cambridge University Press. p. 36. ISBN 9780521186896.

- ^ Zhu, Ruixi; 朱瑞熙 (2016). A social history of middle-period China : the Song, Liao, Western Xia and Jin dynasties. Bangwei Zhang, Fusheng Liu, Chongbang Cai, Zengyu Wang, Peter Ditmanson, Bang Qian Zhu (Updated ed.). Cambridge, United Kingdom. pp. 6, 33. ISBN 978-1-107-16786-5. OCLC 953576345.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Silberstein, Rachel (2020). A fashionable century : textile artistry and commerce in the late Qing. Seattle. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-295-74719-4. OCLC 1121420666.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Burkus, Anne Gail (2010). Through a forest of chancellors : fugitive histories in Liu Yuan's Lingyan ge, an illustrated book from seventeenth-century Suzhou. Yuan, active Liu. Cambridge, Mass. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-68417-050-0. OCLC 956711877.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Costume in the Song Dynasty". en.chinaculture.org. Retrieved 2022-04-01.

- ^ Silberstein, Rachel (2020). A fashionable century : textile artistry and commerce in the late Qing. Seattle. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-295-74719-4. OCLC 1121420666.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Wang, Anita Xiaoming (2018). "The Idealised Lives of Women: Visions of Beauty in Chinese Popular Prints of the Qing Dynasty". Arts Asiatiques. 73: 61–80. doi:10.3406/arasi.2018.1993. ISSN 0004-3958. JSTOR 26585538.

- ^ "History of Traditional Chinese Attire - Beizi - 2021". www.newhanfu.com. 2020. Archived from the original on 2021-02-26. Retrieved 2021-05-22.

- ^ "What's the Difference between "Cloak" and "Cape" in Hanfu?". www.newhanfu.com. 2019. Archived from the original on 2021-02-26. Retrieved 2021-05-22.

- ^ "History of Traditional Chinese Attire - Beizi - 2021". www.newhanfu.com. 2020. Archived from the original on 2021-02-26. Retrieved 2021-04-05.

- ^ a b Bonds, Alexandra B. (2008). Beijing opera costumes : the visual communication of character and culture. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-1-4356-6584-2. OCLC 256864936.

- ^ "Zimu Kou - Exquisite Ming Style Hanfu Button - 2021". www.newhanfu.com. 25 May 2021. Retrieved 2021-06-24.

- ^ Ge, Liangyan (2015). The scholar and the state : fiction as political discourse in late imperial China. Seattle. ISBN 978-0-295-80561-0. OCLC 1298401007.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e Bonds, Alexandra B. (2019). Beijing opera costumes : the visual communication of character and culture. New York, NY. pp. 53, 124, 330–331. ISBN 978-1-138-06942-8. OCLC 1019842143.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "清中期 納紗繡戯服男帔". www.metmuseum.org. Archived from the original on 2016-04-07. Retrieved 2021-07-04.

- ^ Park, Sun-Hee; Hong, Na-Young (2011). "A Study on Hakchangui, the Scholar's Robe with Dark Trim". Journal of the Korean Society of Costume. 61 (2): 60–71. ISSN 1229-6880.

- ^ Kim, Da Eun; Cho, Woo Hyun (2019-11-30). "A Study on Hakchanguis between the 17th and 18th Century : Focused on Confucian Clothing Portraits by Jang Man". Journal of the Korean Society of Costume. 69 (7): 18–33. doi:10.7233/jksc.2019.69.7.018. ISSN 1229-6880. S2CID 214069662.

- ^ "Vietnamese Traditional Costumes: History, Culture and Where to Find Them". Áo dài Cô Sáu. Retrieved 2021-06-24.

- ^ "Áo Nhật Bình - Nét đẹp cổ phục Việt Nam thời nhà Nguyễn". Dayvetrenvai.com. Retrieved 2021-06-24.

- ^ "Beauty and historical value of Vietnamese ancient costumes in Nhat Binh ao dai". Vietnam Times. 2020-10-05. Retrieved 2021-06-24.