Constitution of Ohio

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2008) |

The Constitution of the State of Ohio is the basic governing document of the State of Ohio, which in 1803 became the 17th state to join the United States of America. Ohio has had three constitutions since statehood was granted.

Ohio was created from the easternmost portion of the Northwest Territory. In 1787, the Congress of the Confederation of the United States passed the Northwest Ordinance, establishing a territorial government and providing that "[t]here shall be formed in the said territory, not less than three nor more than five states." The Ordinance prohibited slavery and provided for freedom of worship, the right of habeas corpus and trial by jury, and the right to make bail except for capital offenses.[1] Ohio courts have noted that the Northwest Ordinance "was ever considered as the fundamental law of the territory."[2]

1802 Constitution

[edit]The Ohio territory's population grew steadily in the 1790s and early 19th century. Congress passed an enabling bill to establish a new state, which President Thomas Jefferson signed into law on April 30, 1802. A state constitutional convention was held in November 1802 in Chillicothe, Ohio, and it adopted what became known as the 1802 Constitution. Largely due to the perception that territorial governor Arthur St. Clair had ruled heavy-handedly, the constitution provided for a "weak" governor and judiciary, and vested virtually all power in a bicameral legislature, known as the General Assembly. Congress simply recognized the existence of the "state of Ohio" rather than passing a separate resolution declaring Ohio a state as it had done and would do with other new states. On February 19, 1803, President Jefferson signed the bill into law. It provided that Ohio "had become one of the United States of America," and that Federal law "shall have the same force and effect within the said State of Ohio, as elsewhere within the United States." Scholars Stephen H. Steinglass and Gino J. Scarselli suggest that St. Clair's Federalist affiliation played a key role in the hasty passage, given that most Ohioans sided with Jefferson's Republican Party.[3]

Many tax protesters use this as an argument that Ohio was not a state until 1953. But see Bowman v. United States, 920 F. Supp. 623 n.1 (E.D. Pa. 1995) (discussing the 1953 joint Congressional resolution that confirmed Ohio's status as a state retroactive to 1803).[4]

The first General Assembly first met in Chillicothe, the new state capital, on March 1, 1803. This has come to be considered the date of Ohio statehood.

Judge Charles Willing Byrd was the primary author of the document. He used the 1796 constitution of Tennessee as a model, with those of Pennsylvania and Kentucky as other influences. Provisions in the constitution included a ban on slavery but also included a prohibition on African American suffrage.[3] The constitution provided for amendment only by convention. An attempt in 1819 was rejected by voters.[5]: 484

1851 Constitution

[edit]In the early decades of statehood, it became clear that the General Assembly was disproportionately powerful as compared to the executive and judicial branches. Much of state business was conducted through private bills, and partisan squabbling greatly reduced the ability of state government to do its work. The legislature widely came to be perceived as corrupt, subsidizing private companies and granting special privileges in corporate charters. State debt also exploded between 1825 and 1840. A new constitution, greatly redressing the checks and balances of power, was drafted by a convention in 1850-51, as directed by the voters, and subsequently adopted in a statewide referendum on June 17, 1851, taking effect on September 1 of that year. This is the same constitution under which the state of Ohio operates. The later "constitutions" were viewed as such, but in reality were large-scale revisions.[5]: 483

Two key issues debated at the convention were African American suffrage and prohibition of alcohol. Delegates rejected proposals to allow Black suffrage in the state. They did not decide on prohibition, however. Instead, a second question asked Ohio voters if they wished to permit the licensing of alcohol sales, who rejected the proposition. This did not constitute a complete prohibition on alcohol, however.[3]

1873 Constitutional Convention

[edit]

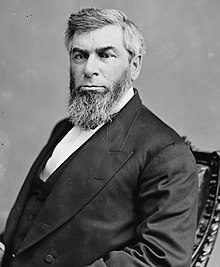

A constitutional convention in 1873, chaired by future Chief Justice of the United States Morrison R. Waite, proposed a new constitution that would have provided for annual sessions of the legislature, a veto for the governor which could be overridden by a three-fifths vote of each house, establishment of state circuit courts, eligibility of women for election to school boards, and restrictions on municipal debt. Delegates proposed the creation of circuit courts to relieve the Ohio Supreme Court's backlog of cases. The proposed document also made these circuits the final arbiter of facts. Waite took a leading role in this specific proposal.[6] It was soundly defeated by the voters in August 1873. A key provision which led to the defeat was another attempt to permit the licensing of liquor sales. Prohibition advocates rallied popular support against the proposal.[3]

In 1903, an amendment granted the governor veto powers.[3]

1912 Constitution

[edit]In the Progressive Era, pent-up demand for reform led to convening the Ohio Constitutional Convention (1912). The delegates were generally progressive in their outlook, and noted Ohio historian George W. Knepper wrote, "It was perhaps the ablest group ever assembled in Ohio to consider state affairs." Several national leaders addressed the convention, including President William Howard Taft, an Ohioan; former president (and Bull Moose Party candidate) Theodore Roosevelt; three-time presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan; California's progressive governor Hiram Johnson; and Ohio's own reform-minded Gov. Judson Harmon.[3]

Recalling how the 1873 convention's work had all been for naught, the 1912 convention drafted and submitted to the voters a series of amendments to the 1851 Constitution. The amendments expanded the state's bill of rights, provided for voter-led initiative and referendum, established civil service protections, and granted the governor a line-item veto in appropriation bills. Other amendments empowered the legislature to fix the hours of labor, establish a minimum wage and a workers compensation system, and address a number of other progressive measures. A home rule amendment was proposed for Ohio cities with populations over 5,000.[5]: 485

On September 3, 1912, despite strong conservative opposition, voters adopted 34 of the 42 proposed amendments. It was so sweeping a change to the 1851 Constitution that most legal scholars consider it to have become a new "1912 Constitution." Among the eight losing proposed amendments were female suffrage, the use of voting machines, the regulation of outdoor advertising and abolition of the death penalty. Voters also rejected a proposal to strike the word "white" from the 1851 Constitution's definition of voter eligibility. Although black people could vote in all State and Federal elections in Ohio due to the Fifteenth Amendment, the text of the State Constitution was not changed until 1923.[7] Urban voters propelled most the amendments to passage. Rural voters rejected most of them.[3]

In 1969, the General Assembly established the Ohio Constitutional Revision Commission. This commission made a number of recommendations to the General Assembly regarding amendments to the constitution. The legislature ended up submitting sixty amendments to the people, many of which were passed.[3]

A similar commission, the Ohio Constitution Modernization Commission, was established in 2011. The legislature failed to propose most of its recommendations and terminated it before its intended sunset date of 2020. The main success of the commission came in reforming the process of apportionment in Ohio, which eventually led to the establishment of the state's redistricting commission.[3]

Current constitution

[edit]The original 1851 constitution had 16 articles and 169 sections. The present document has 19 articles and 225 sections. There have been 170 amendments made. Most amendments occurred after 1912, when the requirements for passing amendments loosened.[8]

The current state constitution contains the following articles:

Preamble

[edit]We, the people of the State of Ohio, grateful to Almighty God for our freedom, to secure its blessings and promote our general welfare, do establish this Constitution

— Ohio Constitution, Preamble

While the preamble does not enact any positive laws, the Ohio Supreme Court has established that it creates a presumption that the legislature enacts law to promote Ohioans' "general welfare."[9]

Article I - Bill of Rights

[edit]Much of Ohio's bill of rights has been in place since the passage of the Northwest Ordinance. The writers of the 1802 constitution borrowed heavily from this document, and those of the 1851 constitution made few changes. Voters approved only nine amendments since then.[10]

Many of the rights found within the state constitution align with the U.S. Constitution. These include the right to assemble (section 3), the right to bear arms (section 4), and protections against cruel and unusual punishment (section 9).[10] The Ohio Supreme Court holds that "the Ohio Constitution is a document of independent force," however. Ohio courts are free to grant Ohioans greater rights than those afforded under federal law.[11] Additionally, the Ohio Constitution contains several rights not found in the U.S. Constitution. For example, the 1851 constitution outlawed slavery, but slavery remained legal under the U.S. Constitution until the passage of the 13th Amendment in 1865.[10][12] Additionally, in 2011, voters passed an amendment prohibiting residents from being required to purchase health insurance. This amendment targeted the Affordable Care Act, which had recently instituted a federal individual mandate.[13] More recently, in 2023, Ohioans passed an amendment to guarantee access to abortion in the wake of Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization. Litigation continues as to the constitutionality of an existing statutory ban, however.[14][15]

Article II - Legislative

[edit]

Article II lays out the power of Ohio's legislature, the General Assembly. The original 1802 constitution made the legislature the most powerful branch of the state government. It appointed most executive branch officers and judges, and the governor lacked a veto over its decisions. The 1851 constitution eliminated this appointment power, although Ohio governors lacked a veto until 1903.[16] Ohio judges still grant the legislature substantial leniency, however. The state supreme court, for example, considers that "all statutes are presumed constitutional."[17] One unusual provision requires that legislative vacancies be filled by an appointment of the members of the former legislators' political member within the legislature (not an outside body). Ohio is the only state to use this method.[18]

Since 1912, this article has been frequently amended. One notable amendment in 1918 gave voters the power to review legislative ratification of amendments to the U.S. Constitution. The U.S. Supreme Court, however, found this provision unconstitutional two years later in Hawke v. Smith.[19] More generally, article II also grants voters powers of initiative and referenda.[20] This power extends to the creation of new counties, but no new county has been created since the constitution was ratified in 1851.[16]

Article III - Executive

[edit]Article III details the state's executive branch, including the governor and other statewide officers. Initially, the governor lacked substantial power, and Ohioans were slow to expand the power of that office. It was not until 1903, for example, that governors gained a veto power.[21] The article also contains little information on the power of other constitutional officers. The powers of officials such as the attorney general is usually construed based on "common law" interpretations thereof.[22] Most of the article deals with the powers and duties of the governor.

Article IV - Judicial

[edit]

Article IV describes the state's judicial system. The constitution creates three tiers—the Supreme Court of Ohio, the Ohio District Courts of Appeals, and the Ohio Courts of Common Pleas. The legislature can create additional courts as well.[23] In 1968, voters adopted the "Modern Courts Amendment" which significantly revised this article. The key change was granting the Supreme Court administrative control of the state's judiciary. Before, each judge was largely independent of any oversight.[24]: 822 This power extended to creating rules for judicial practice.[24]: 829 Section 22 also gives the governor the power to appoint a five-member commission to hear cases appealed to the Supreme Court. The provision has been invoked twice in 1876 and 1883. Legal scholars Steven Steinglass and Gino Scarselli note that "with the creation of this commission, Ohio literally had two supreme courts functioning simultaneously."[23] Decisions of this commission were considered equivalent to Supreme Court decisions and act as binding precedent.[25]

Unusually, the constitution once prohibited the Supreme Court from striking down laws as unconstitutional unless six out of the seven justices agreed. The justices could also uphold an appellate court's ruling that a law was unconstitutional.[23] This created the unusual situation that a law could be held unconstitutional in one appellate district but not others. The 1968 amendment repealed this provision.[24]: 845

Article V - Elective Franchise

[edit]Article V outlines the state's electoral system, including voting rights and term limits. Section 1 establishes the requirements to vote in the state, including requiring voters to register at least thirty days before an election and mandating the removal of inactive voters after four years. The latter requirement was added in 1977.[26] In 2014, it was challenged for violating the National Voter Registration Act, but the Supreme Court of the United States upheld the requirement in Husted v. Randolph Institute.[27] Section 6 prohibits "idiot[s]" and "insane person[s]" from voting. Attempts to remove this provision have failed, although Ohio statutes require a judicial examination of an individual before ineligibility occurs.[26][28]

Section 8 previously imposed term limits on federal representatives and senators. In 1995, this section was struck down as unconstitutional by the Supreme Court of the United States in U.S. Term Limits, Inc. v. Thornton.[26]

Article VI - Education

[edit]Article VI details the state's powers regarding education. Ohio has a long history of education being a public service. The initial 1802 constitution prohibited laws to prevent poor children from receiving an education.[29] Federal law at the time also granted the state significant lands to sell for the benefit of schools. The funds from these antebellum land sales are still held in trust for the state's schools.[30] The 1851 constitution required the establishment of a public school system. Common school advocates successfully lobbied the convention delegates to recognize education as a right of every child, and every draft of the constitution included such a requirement, which is still present in section 2.[31]: 612–613 Even so, the Ohio Supreme Court has suggested the education is in fact, not, a right guaranteed to Ohioans by the state's constitution in the case of Board of Education v. Walter.[32] Section 3 gives the state ultimate responsibility over public schools, though it also allows the creation of local school districts by referendum. This provision was added in 1912 in order to prevent local governments from refusing to establish public schools.[31]: 634–635

Several provisions of the article also deal with funding for education. Section 5, for example, permits the state government to provide student loans for higher education, though it does not do so in practice. Section 6, meanwhile, creates a tuition credit system similar to a 529 plan.[29] On a broader note, in 1997, the state supreme court ruled against the state's traditional use of property taxes to fund education in the case of DeRolph v. State.[33]: 107 The state legislature soon took action to rectify the matter by proposing a ballot initiative to raise sales taxes, which voters overwhelmingly rejected.[33]: 118 Voters also approved a constitutional amendment in 1999 to permit the sale of bonds to fund Ohio schools. The supreme court again held the system to be unconstitutional, however.[33]: 120 Other attempts to rectify the matter legislatively were rejected, but the court eventually granted a writ of prohibition to halt the case in 2003.[29]

Article VII - Public Institutions

[edit]This article obligates the state government to support institutions to treat those with mental illness, blindness, or deafness. It has never been amended, and efforts to do so have repeatedly failed to pass the legislature.[34] The state continues to operate these facilities, viz. the Ohio State School for the Blind, the Ohio School for the Deaf, and six psychiatric hospitals run by the Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services.

Article VIII - Public Debt and Public Works

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2024) |

The longest and most frequently amended article, Article VIII deals with public debt and public works. Thirty amendments to the constitution have been passed by voters, with twenty-five dealing solely with giving the state government more authority to borrow money.[35]

Article IX - Militia

[edit]Article IX establishes the state's militia under the command of the governor. Section 1 states that all Ohioans between the ages of 17 and 67 are eligible to be called upon to serve. In practice, however, the organized Ohio National Guard serves as the state's militia.[36]

Article X - County and Township Organizations

[edit]This article lays out the structure of local government in the state, which is based on counties and townships. Both entities were created by the Northwest Ordinance and retained following statehood. When passed initially in 1851, the article contained little detail beyond granting local governments the authority to tax. In 1933, however, a substantial revision was passed which introduced home rule to the state. Counties must adopt charters, however, before utilizing their home rule authority.[37]

Article XI - Apportionment

[edit]This article discusses the apportionment of the Ohio Legislature. (Apportionment for congressional districts are discussed by Article XIX). Unlike in most states, where legislatures control the redistricting process, Ohio has a long history of using a commission to apportion the state legislative districts. This commission was implemented by the original 1851 Constitution and consisted of the governor, the state auditor, and the secretary of state. Between 1903 and the Supreme Court's decision in Reynolds v. Sims in 1964, the constitution mandated that state legislative districts be based on county lines. This practice continued as a de facto rule during the late twentieth century, however.[38]

Following several instances of partisan gerrymandering, various initiatives were proposed to amend the article. Attempts in 1981, 2005, and 2012 to create a non-partisan commission failed. In 2015, an initiative to create a bipartisan process passed. The amendment expanded the commission to seven members, including appointees of the state's legislative minority leaders. Support from members of both parties was required to pass a plan, though a partisan majority could pass a temporary proposal if no agreement was reached. Partisan gerrymandering is also now explicitly prohibited.[39]

This process was first implemented during the 2021-22 redistricting cycle. The commission failed to reach a bipartisan agreement, so a 5-2 Republican majority implemented a temporary plan. In January 2022, however, the Ohio Supreme Court rejected the plan, finding that it violated the article's anti-gerrymandering provisions. The commission then proceeded to adopt five additional plans, which the state supreme court rejected.[38] A federal court finally intervened and ordered the adoption of one of the rejected plans to ensure a plan was in place for elections that fall.[40] In September 2023, the commission finally reached an agreement to implement a bipartisan plan. Despite the agreement, Republicans remained favored in the new plan, and Democrats renewed calls for a fully non-partisan commission.[41]

This article discusses finance and taxation. The original 1802 constitution gave the legislature nearly unlimited leeway in terms of taxing Ohioans, but the 1851 constitution imposed significant restrictions on that power. The majority of the article deals with specific forms of taxation, including poll taxes (which are prohibited by section 1), property taxes, and sales taxes. Two sections also deal with the payment of debts by both the state and local governments.[42]

Article XIII - Corporations

[edit]Article XIII was adopted in 1851 largely as a response to a series of entanglements between the state government and corporations in the early nineteenth century. The article institutes general regulations for corporations and prohibits the legislature from granting special powers such as eminent domain to private companies.[43]

Article XIV - Ohio Livestock Care Standards Board

[edit]In the original 1851 constitution, Article XIV dealt with the rules of civil procedure. It created a three-person commission to devise a code of civil procedure for the state. The commission met in 1852 and crafted such a code based on New York's Field Code, which was used until 1970.[44] Beforehand, the state relied simply on common law practice.[45] This article was repealed in 1953.

In 2009, the legislature proposed to create the Ohio Livestock Care Standards Board and decided to include it under Article XIV in the constitution. Proponents of the measure argued that the board would ensure Ohio livestock were properly cared for. Journalist Jim Provance noted that the legislature's proposal was intended to ward off a competing proposal by animal rights groups. The legislature's proposal was seen as more friendly to agribusiness than the alternative.[46] Despite this tension, voters overwhelmingly approved the measure.[47] The new article established the thirteen-member board and gave it the power to establish standards for livestock care. The Ohio Department of Agriculture is responsible for enforcement.[44]

Article XV - Miscellaneous

[edit]Article XV contains several miscellaneous provisions. These provisions include naming Columbus as the state capital and mandating the regular publication of the state's financial accounts.[48]

A major portion of the article deals with gambling laws. The original 1851 document prohibited lotteries in the state. Over time, rules have been relaxed. In the early twentieth century, both horse racing and bingo became de facto allowed, though it was not until 1975 that an amendment was passed to de jure legalize bingo.[48] (The legislature had already decriminalized bingo in 1943).[49] Similarly, in 1973, the article was amended to create the Ohio Lottery.[48]

One final amendment came in 2009 with the legalization of casino gambling. Several prior attempts at legalizing gambling had failed.[48] Major gambling companies like Penn Entertainment supported the measure, which permitted the establishment of four casinos in the state, citing the potential for economic growth.[50] Several groups opposed the measure, including religious conservatives and horse racetrack owners, who feared competition for horse racing and charitable bingoes.[51] Ultimately, the amendment was narrowly passed.[52]

Article XVI - Amendments

[edit]This article lays out the two original ways that the constitution can be amended. First, the state legislature can propose amendments by a three-fifths vote. Voters then either approve or reject the proposed amendment. (Before 1912, a majority of voters who voted in the election as a whole was required to pass an amendment. Since then, only a majority of those voting on the amendment is required). Second, amendments can be proposed by a constitutional convention. These conventions can be called either by a two-thirds majority of the legislature or by voters in referenda which must be held every twenty years. No such convention has been held since 1912.[53] The other method that can be used to amend the constitution, initiative, is described in Article II.

Article XVI also lays out general rules for amendments. Specifically, it requires that ballot language be approved by a five member board consisting of the Secretary of State and four others.[53] (The four other members are appointed by the state's legislative leaders to ensure partisan balance).[54] Additionally, the state supreme court has original jurisdiction over disputes over the approved language. Both of these elements were added in 1974.[53]

Article XVII lays out general rules for elections. Elections for state and county offices occur in even-numbered years, while those for local offices occur in odd-numbered years. Terms are limited to four years in length (six for judges) but can be shorter. Additionally, the governor has the power to appoint certain officials in cases of vacancy.[55]

Article XVIII - Municipal Corporations

[edit]This article was added in 1912 to give home rule to the state's municipalities. The original 1851 constitution gave the legislature to enact general laws for the establishment of municipalities. Over time, however, the need to differentiate between municipalities arose based on population. The legislature thus enacted laws that created different classifications for municipalities.[56]: 9–10 In 1902, however, the state supreme court declared this system unconstitutional because the constitution also prohibited the state from granting special powers to corporations (which municipalities were deemed to be). The legislature passed a temporary solution, but city leaders found it inadequate.[56]: 12–13 As a result, the 1912 convention adopted this new article to properly codify the classification system.[57]

The article creates a two-tiered system of classification. Municipalities with over 5,000 people are deemed cities, while those with less than 5,000 people are considered villages. The legislature still passes a general law to provide for municipal powers, but this article also allows for "additional laws" to be passed for municipal governments.[57] (Originally, the text read "special laws," but legal scholar Harvey Walker states that delegates found this language "obnoxious").[56]: 14 Additionally, municipalities can adopt home rule charters laying out their powers. The remainder of the article deals primarily with public utilities and other broad instances of municipal power.[57]

Article XIX - Congressional Redistricting

[edit]Article XIX was added by a referendum in 2018. It passed with nearly 75% of the vote.[58] The article requires a 3/5 vote of the state legislature to approve any redistricting plan, provided that half of each party votes in favor. If the legislature cannot reach an agreement, a commission creates a plan. This plan must receive approval from four members, including two members from each of the two largest political parties. If the commission cannot reach an agreement, the legislature may pass a plan by a simple majority vote. The article also lays out certain requirements for districts, including mandating partisan neutrality and limiting county and municipality splits. The state supreme court has sole jurisdiction over the constitutionality of any plan passed.[59]

Article XIX first took effect in January 2021 and governed the state's redistricting cycle that year. The legislature failed to create a plan, forcing the redistricting commission to take charge.[60] The commission also failed to reach an agreement, turning the job back to the legislature.[61] Eventually, the legislature passed a new map by simple majority vote.[62] However, the state supreme court rejected the maps, finding it unconstitutionally favored Republicans.[63] The legislature refused to adopt new maps, sending the process back to the commission.[64] The commission adopted the final set of maps in March 2022.[65] In July, the state supreme court again rejected the maps. However, because congressional primaries had already occurred, the maps will be used for the 2022 election.[66]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ State v. Bob Manashian Printing, 121 Ohio Misc. 2d 99, 103 (Cleveland Muni. Ct. 2002).

- ^ The Heirs of Israel Ludlow v. C. and J. Johnson, 3 Ohio 553, 560 (Ohio Sup. Ct. 1828).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Steinglass & Scarselli 2022, introduction.

- ^ "The Truth About Frivolous Tax Arguments - Section I". Internal Revenue Service. November 30, 2006. Archived from the original on October 18, 2007. Retrieved 2012-06-26.

- ^ a b c Ohio Constitutional Revision Commission (May 1, 1977). Recommendations for Amendments to the Ohio Constitution - Final Report: Index to Proceedings and Research (PDF). Columbus: Ohio Constitutional Revision Commission.

- ^ Magrath, C. Peter (1963). Morrison R. Waite: The Triumph of Character. New York: Macmillan. p. 88.

- ^ Amendments submitted to the voters Archived 2012-01-31 at the Wayback Machine Ohio Secretary of State see page 6, November 6, 1923

- ^ Steinglass & Scarselli 2022, Introduction.

- ^ Palmer v. Tingle, 55 Ohio St. 423, 440 (December 8, 1896).

- ^ a b c Steinglass & Scarselli 2022, chapter 2.

- ^ Arnold v. City of Cleveland, 67 Ohio St. 3d 35, 42 (August 11, 1993).

- ^ White, Richard (2017). The Republic for Which It Stands. Oxford History of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 29. ISBN 9780190053765.

- ^ Marshall, Aaron (November 9, 2011). "Ohio voters say no to health insurance mandates, older judges". The Plain Dealer. Retrieved June 5, 2023.

- ^ Smyth, Julie Carr (November 7, 2023). "Ohio voters enshrine abortion access in constitution in latest statewide win for reproductive rights". Associated Press. Retrieved May 31, 2024.

- ^ Smyth, Julie Carr (May 19, 2024). "Ohio voters approved reproductive rights. Will the state's near-ban on abortion stand?". Associated Press. Retrieved May 31, 2024.

- ^ a b Steinglass & Scarselli 2022, chapter 3.

- ^ State v. Bozcar, 113 Ohio St. 3d 148, 150 (2007).

- ^ "Filling Legislative Vacancies". National Conference of State Legislatures. February 16, 2023. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- ^ Delliger, Walter (December 1983). "The Legitimacy of Constitutional Change: Rethinking the Amendment Process". Harvard Law Review. 97 (2): 404 – via HeinOnline.

- ^ Article II, Section 1a, 1b, and 1c of the Constitution of Ohio (1851 (amended 1912))

- ^ Steinglass & Scarselli 2022, chapter 4.

- ^ Miller II, Clinton J.; Miller, Terry M. (1976). "Constitutional Charter of Ohio's Attorney General". Ohio State Law Journal. 37 (4): 803 – via HeinOnline.

- ^ a b c Steinglass & Scarselli 2022, chapter 5.

- ^ a b c Milligan, William W.; Pohlman, James E. (1968). "The 1968 Modern Courts Amendment to the Ohio Constitution". Ohio State Law Journal. 29 (4): 811–848 – via HeinOnline.

- ^ Marshall, Carrington T. (1934). A History of the Courts and Lawyers of Ohio. New York: The American Historical Society. pp. 222–223 – via HeinOnline.

- ^ a b c Steinglass & Scarselli 2022, chapter 6.

- ^ Totenberg, Nina (June 11, 2018). "Supreme Court Upholds Controversial Ohio Voter-Purge Law". NPR. Retrieved May 24, 2024.

- ^ Ohio Rev. Code §5122.301

- ^ a b c Steinglass & Scarselli 2022, chapter 7.

- ^ Knepper, George W. (2002). The Official Ohio Lands Book (PDF). Columbus: Ohio Auditor of State. pp. 58–59.

- ^ a b O'Brien, Molly; Woodrum, Amanda (2004). "The Constitutional Common School". Cleveland State Law Review. 51 (3 & 4) – via HeinOnline.

- ^ Board of Education v. Walter, 58 Ohio St. 2d 368, 389 (Locher, J., dissenting) (Ohio 1979-06-13) ("First, I respectfully disagree with the majority's conclusion to the effect that educational opportunity is not a fundamental right...").

- ^ a b c Obhof, Larry J. (2005). "DeRolph v. State and Ohio's Long Road to an Adequate Education". Brigham Young University Education and Law Journal (1): 83–150 – via HeinOnline.

- ^ Steinglass & Scarselli 2022, chapter 8.

- ^ Steinglass & Scarselli 2022, chapter 9.

- ^ Steinglass & Scarselli 2022, chapter 10.

- ^ Steinglass & Scarselli 2022, chapter 11.

- ^ a b Steinglass & Scarselli 2022, chapter 12.

- ^ Beech, Patricia (November 5, 2015). "Issue 1 approved by Ohio voters - Voters Reject Political Monopoly". People's Defender. West Union, OH – via NewsBank.

- ^ Welsh-Huggins, Andrew (May 27, 2022). "Judges impose voided Statehouse map, set Aug. 2 primary". Associated Press – via NewsBank.

- ^ Hendrickson, Samantha (September 27, 2023). "Bipartisan Ohio commission unanimously approves new maps that favor Republican state legislators". Associated Press. Retrieved July 20, 2024.

- ^ Steinglass & Scarselli 2022, chapter 13.

- ^ Steinglass & Scarselli 2022, chapter 14.

- ^ a b Steinglass & Scarselli 2022, chapter 15.

- ^ Blackmore II, Josiah H. (2004). "Not From Zeus's Head Full-Blown: The Story of Civil Procedure in Ohio". In Benedict, Michael Les; Winkler, John F. (eds.). The History of Ohio Law. Ohio University Press. p. 447. ISBN 9780821415467 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Provance, Jim (June 24, 2009). "Ohio lawmakers rush ballot issue to regulate livestock care". The Blade. Toledo, Ohio. pp. A3 – via NewsBank.

- ^ Johnson, Alan (November 4, 2009). "Livestock-care board, help for veterans sail through - Statewide issues pass by overwhelming margins". The Columbus Dispatch. pp. 1A – via NewsBank.

- ^ a b c d Steinglass & Scarselli 2022, chapter 16.

- ^ Ravenscraft, Patricia; Reilly, Elizabeth. "Perspectives on Ohio Bingo Regulation: An Historical Analysis and Proposals for Change". Akron Law Review. 10 (4): 656 – via HeinOnline.

- ^ Nash, James (April 14, 2009). "Casino backers can start petition". The Columbus Dispatch. pp. 1B – via NewsBank.

- ^ "Threat to charity - Latest casino proposal could stop charities' use of gambling nights". The Columbus Dispatch. August 23, 2009. pp. 4G – via NewsBank.

- ^ Fortney, Eric (November 4, 2009). "Issue 3 passes with 53 percent of the vote in Ohio". Akron Examiner – via NewsBank.

- ^ a b c Steinglass & Scarselli 2022, chapter 17.

- ^ Ohio Rev. Code §3505.061

- ^ Steinglass & Scarselli 2022, chapter 18.

- ^ a b c Walker, Harvey (1948). "Municipal Government in Ohio before 1912". Ohio State Law Journal. 9 (1): 1–17 – via HeinOnline.

- ^ a b c Steinglass & Scarselli 2022, chapter 19.

- ^ Exner, Rich (May 9, 2018). "Ohio votes to reform congressional redistricting; Issue 1 could end gerrymandering". Cleveland Plain-Dealer. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- ^ Ohio Constitution, art. XIX

- ^ Amiri, Farnoush (September 30, 2021). "Ohio lawmakers set to miss another redistricting deadline". AP State Wire – via NewsBank.

- ^ Borchardt, Jackie (October 29, 2021). "Ohio Redistricting Commission punts on map". Akron Beacon Journal. p. B1 – via NewsBank.

- ^ Hancock, Aimee; Gaines, Jim (November 20, 2021). "DeWine signs bill establishing new congressional map". Dayton Daily News – via NewsBank.

- ^ Tobias, Andrew J; Pelzer, Jeremy (January 15, 2022). "Ohio Supreme Court again draws the line on gerrymandering The court rejects congressional maps two days after tossing legislative ones; it orders lawmakers to come up with a new one". Cleveland Plain-Dealer. p. 1 – via NewsBank.

- ^ Bischoff, Laura A. (February 10, 2022). "Redistricting must go back to the commission - Lawmakers can't come up with enough votes". Columbus Dispatch. p. A1 – via NewsBank.

- ^ Balmert, Jessie (March 1, 2022). "Ohio Republicans pass a new congressional map. Will it pass Ohio Supreme Court scrutiny?". Columbus Dispatch. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- ^ Balmert, Jessie (July 14, 2022). "Redistricting: Ohio Supreme Court rejects congressional map used in May, orders new one". Columbus Dispatch. Retrieved November 5, 2022 – via Yahoo News.

- Steinglass, Steven H.; Scarselli, Gino J. (2022). The Ohio State Constitution (2nd ed.). Oxford Academic. doi:10.1093/oso/9780197619728.001.0001. ISBN 9780197619759.

External links

[edit]- Ohio's Secretary of State is the custodian of amendments to the Ohio constitution (see Art. XVI, § 1 and O.R.C. § 3501.05 and § 111.08), and maintains an online copy of the current, complete constitution here: https://www.sos.state.oh.us/globalassets/publications/election/constitution.pdf Archived 2019-01-29 at the Wayback Machine

- The original constitution documents are held by the Ohio Historical Society, as mandated by Ohio's General Assembly (O.R.C. § 111.08). The OHS has online copies of the originals' text.

- Ohio's legislature also maintains an online copy of the constitution.

- Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Professor Steven Steinglass and Law Librarian Sue Altmeyer maintain The Ohio Constitution Law and History Web Site. The site has links to historical versions of the Constitution and Constitutional Conventions; a Table of Proposed Amendments and Votes, with ballot or amendment language, where available; current Ohio Supreme Court decisions and upcoming cases pertaining to the Ohio Constitution and a bibliography of relevant books and articles.