Persis

Persis

Περσίς Persís | |

|---|---|

Region | |

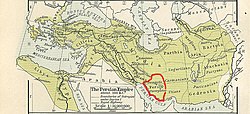

The Persian Empire, about 500 BC; Persis is the central southern province with the red outline. Its main cities are Persepolis and Pasargadae. |

Persis (‹See Tfd›Greek: Περσίς, romanized: Persís; Old Persian: 𐎱𐎠𐎼𐎿, romanized: Parsa),[1] also called Persia proper, is a historic region in southwestern Iran, roughly corresponding with Fars province. The Persians are thought to have initially migrated either from Central Asia or, more probably, from the north through the Caucasus.[2] They would then have migrated to the current region of Persis in the early 1st millennium BC.[2] The country name Persia was derived directly from the Old Persian Parsa.

Achaemenid Empire

[edit]

The ancient Persians were present in the region of Persis from about the 10th century BC. They became the rulers of the largest empire the world had yet seen under the Achaemenid dynasty which was established in the late 6th century BC, at its peak stretching from Thrace-Macedonia, Bulgaria-Paeonia and Eastern Europe proper in the west, to the Indus Valley in its far east.[5] The ruins of Persepolis and Pasargadae, two of the four capitals of the Achaemenid Empire, are located in Fars.

Macedonian Empire

[edit]The Achaemenid Empire was defeated by Alexander the Great in 330 BC, incorporating most of their vast empire.

Several Hellenistic satraps of Persis are known (following the conquests of Alexander the Great) from circa 330 BC, especially Phrasaortes, who ruled from 330 to 324 BC; Orxines, who usurped his position and was then executed by Alexander; and the Macedonian general Peucestas, who learned the Persian language and followed local customs, implementing a persophile policy.[6][7][8] Peucestas retained the satrapy of Persis until the Battle of Gabiene (316 BC), after which he was removed from his position by Antigonus.[8] A short period of Antigonid rule followed, until Seleucus took possession of the region in 312 BC.[7]

Seleucid Empire

[edit]

When the Seleucid Empire was established, it possibly never extended its power beyond the main trade routes in Fars, and by the reign of Antiochus I or possibly later, Persis emerged as a state with a level of independence that minted its own coins.[10]

- "Frataraka" Governors of the Seleucid Empire

Several later Persian rulers, forming the Frataraka dynasty, are known to have acted as representatives of the Seleucids in the region of Fārs.[11] They ruled from the end of the 3rd century BC to the beginning of the 2nd century BC, and Vahbarz or Vādfradād I obtained independence circa 150 BC, when Seleucid power waned in the areas of southwestern Persia and the Persian Gulf region.[8]

Kings of Persis, under the Parthian Empire

[edit]

During an apparent transitional period, corresponding to the reigns of Vādfradād II and another uncertain king, no titles of authority appeared on the reverse of their coins. The earlier title prtrk' zy alhaya (Frataraka) had disappeared. Under Dārēv I however, the new title of mlk, or king, appeared, sometimes with the mention of prs (Persis), suggesting that the kings of Persis had become independent rulers.[12]

When the Parthian Arsacid king Mithridates I (ca. 171-138 BC) took control of Persis, he left the Persian dynasts in office, known as the Kings of Persis, and they were allowed to continue minting coins with the title of mlk ("King").[11][13]

Sasanian Empire

[edit]

Babak was the ruler of a small town called Kheir. Babak's efforts in gaining local power at the time escaped the attention of Artabanus IV, the Arsacid Emperor of the time. Babak and his eldest son Shapur managed to expand their power over all of Persis.

The subsequent events are unclear, due to the sketchy nature of the sources. It is however certain that following the death of Babak around 220, Ardashir who at the time was the governor of Darabgird, got involved in a power struggle of his own with his elder brother Shapur. The sources tell us that in 222, Shapur was killed when the roof of a building collapsed on him.

Ardaxšir (Artaxerxes) V, defeated the last legitimate Parthian king, Artabanos V in AD 224, and was crowned at Ctesiphon as Ardaxšir I (Ardashir I), šāhanšāh ī Ērān, becoming the first king of the new Sasanian Empire.[12]

At this point, Ardashir moved his capital further to the south of Persis and founded a capital at Ardashir-Khwarrah (formerly Gur, modern day Firouzabad).[14] After establishing his rule over Persis, Ardashir I rapidly extended the territory of his Sassanid Persian Empire, demanding fealty from the local princes of Fars, and gaining control over the neighboring provinces of Kerman, Isfahan, Susiana, and Mesene.

Artabanus marched a second time against Ardashir I in 224. Their armies clashed at Hormizdegan, where Artabanus IV was killed. Ardashir was crowned in 226 at Ctesiphon as the sole ruler of Persia, bringing the 400-year-old Parthian Empire to an end, and starting the virtually equally long rule of the Sassanian Empire, over an even larger territory, once again making Persia a leading power in the known world, only this time along with its arch-rival and successor to Persia's earlier opponents (the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire); the Byzantine Empire.

The Sassanids ruled for 425 years, until the Muslim armies conquered the empire. Afterward, the Persians started to convert to Islam, this making it much easier for the new Muslim empire to continue the expansion of Islam.

Persis then passed hand to hand through numerous dynasties, leaving behind numerous historical and ancient monuments; each of which has its own values as a world heritage, reflecting the history of the province, Iran, and West Asia. The ruins of Bishapur, Persepolis, and Firouzabad are all reminders of this. Arab invaders brought about a decline of Zoroastrian rule and made Islam ascendant from the 7th century.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Richard Nelson Frye (1984). The History of Ancient Iran, Part 3, Volume 7. C.H.Beck. pp. 9–15. ISBN 9783406093975.

- ^ a b Dandamaev, Muhammad A.; Lukonin, Vladimir G. (2004). The Culture and Social Institutions of Ancient Iran. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–5. ISBN 9780521611916.

- ^ "cylinder seal | British Museum". The British Museum.

- ^ "Darius' seal, photo - Livius". www.livius.org.

- ^ David Sacks, Oswyn Murray, Lisa R. Brody; Oswyn Murray; Lisa R. Brody (2005). Encyclopedia of the ancient Greek world. Infobase Publishing. pp. 256 (at the right portion of the page). ISBN 978-0-8160-5722-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Roisman, Joseph (2002). Brill's Companion to Alexander the Great. BRILL. p. 189. ISBN 9789004217553.

- ^ a b Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh; Stewart, Sarah (2010). The Age of the Parthians. I.B.Tauris. p. 38. ISBN 9780857710185.

- ^ a b c Foundation, Encyclopaedia Iranica. "Welcome to Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org.

- ^ "CNG: Feature Auction CNG 96. KINGS of PERSIS. Vādfradād (Autophradates) I. 3rd century BC. AR Tetradrachm (28mm, 15.89 g, 9h). Istakhr (Persepolis) mint". www.cngcoins.com.

- ^ The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol. 3 (1), p. 299

- ^ a b FRATARAKA – Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ^ a b "CNG: Feature Auction CNG 90. KINGS of PERSIS. Vahbarz (Oborzos). 3rd century BC. AR Obol (10mm, 0.50 g, 11h)". www.cngcoins.com.

- ^ The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol. 3 (1), p. 302

- ^ Kaveh Farrokh (2007). Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War. Osprey Publishing. pp. 176–9. ISBN 9781846031083.