Ordination of women: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:Wiccan priestess preaching, USA.PNG|thumb|right|A female Wiccan priest preaching.]] |

|||

[[File:Izabela.JPG|thumb|right|250px|Izabela Wiłucka-Kowalska ─ the first female bishop in Poland (1929)]] |

[[File:Izabela.JPG|thumb|right|250px|Izabela Wiłucka-Kowalska ─ the first female bishop in Poland (1929)]] |

||

[[Ordination]] in general religious use is the process by which a person is [[Consecration|consecrated]] (set apart for the administration of various religious rites). The '''ordination of women''' is a controversial issue in those religions or denominations where either the rite of ordination, or the role that an ordained person fulfills, has traditionally been restricted to men because of cultural prohibitions, theological doctrines, or both. |

[[Ordination]] in general religious use is the process by which a person is [[Consecration|consecrated]] (set apart for the administration of various religious rites). The '''ordination of women''' is a controversial issue in those religions or denominations where either the rite of ordination, or the role that an ordained person fulfills, has traditionally been restricted to men because of cultural prohibitions, theological doctrines, or both. |

||

| Line 15: | Line 16: | ||

Within [[Buddhism]], the legitimacy of ordaining women as [[bhikkhuni]] (nuns) has become a significant topic of discussion in some areas in recent years. It is widely accepted that the [[Gautama Buddha|Buddha]] created an order of bhikkhuni, but the tradition of ordaining women has died out in some Buddhist traditions, such as [[Theravada Buddhism]], while remaining strong in others, such as [[Chinese Buddhism]].<ref name=Wheaton98/> |

Within [[Buddhism]], the legitimacy of ordaining women as [[bhikkhuni]] (nuns) has become a significant topic of discussion in some areas in recent years. It is widely accepted that the [[Gautama Buddha|Buddha]] created an order of bhikkhuni, but the tradition of ordaining women has died out in some Buddhist traditions, such as [[Theravada Buddhism]], while remaining strong in others, such as [[Chinese Buddhism]].<ref name=Wheaton98/> |

||

Wiccans ordain women [http://dianic-wicca.com/dianic-wicca-clergy.html]. They are called Wiccan priestesses or priests (a woman may be called either word, as she prefers, but a man is always called a priest.) |

|||

== Buddhism == |

== Buddhism == |

||

Revision as of 19:28, 11 July 2010

Ordination in general religious use is the process by which a person is consecrated (set apart for the administration of various religious rites). The ordination of women is a controversial issue in those religions or denominations where either the rite of ordination, or the role that an ordained person fulfills, has traditionally been restricted to men because of cultural prohibitions, theological doctrines, or both.

History

In the liturgical traditions of Christianity including the Roman Catholic Church, Eastern and Oriental Orthodoxy, Lutheranism, and Anglicanism, ordination—distinguished from religious or consecrated life—is the means by which a person is included in one of the orders of bishops, priests, or deacons.

Many Protestant denominations understand ordination more generally as the acceptance of a person for pastoral work. In the late eighteenth century in England, John Wesley allowed for female office-bearers and preachers. It has been part of British Methodist tradition for over 200 years, and continued in the Salvation Army.[1]

Today, about half of all American Protestant denominations ordain women, but some restrict the official positions a woman can hold. For instance, some ordain women for the military or hospital chaplaincy but prohibit them from serving in pastoral roles. About 30% of all seminary students (and in some seminaries over half) are female.[2] By contrast, in 1956 the United Methodist Church was the first American Protestant denomination to approve full ordination and clergy rights for women.

Orthodox Judaism does not permit women to become rabbis (instead, the women in leadership positions are often rebbetzin, wives of rabbis), but all other types of Judaism allow and have female rabbis; these types are Humanistic Judaism, Jewish Renewal, Reconstructionist Judaism, Reform Judaism, and Conservative Judaism (see Women as rabbis).[2]

Muslims do not formally ordain religious leaders. The imam serves as a spiritual leader and religious authority. Most strands of Islam permit women to lead female-only congregations in prayer (one of the competences of an imam), but restrict their roles in mixed-sex congregations. There is a recent movement to extend women's roles in spiritual leadership.[2]

Within Buddhism, the legitimacy of ordaining women as bhikkhuni (nuns) has become a significant topic of discussion in some areas in recent years. It is widely accepted that the Buddha created an order of bhikkhuni, but the tradition of ordaining women has died out in some Buddhist traditions, such as Theravada Buddhism, while remaining strong in others, such as Chinese Buddhism.[2]

Wiccans ordain women [75]. They are called Wiccan priestesses or priests (a woman may be called either word, as she prefers, but a man is always called a priest.)

Buddhism

The ordination of women is currently and historically practiced in some Buddhist regions, such as East Asia and Taiwan, and now once again in India and Sri Lanka.

The tradition of the ordained monastic community (sangha) began with the Buddha, who established an order of Bhikkhus (monks).[3] According to the scriptures,[4] later, after an initial reluctance, he also established an order of Bhikkhunis (nuns or women monks).

In 2010 the first Buddhist nunnery in North America was established in Vermont.[5] It is a Tibetan Buddhist nunnery. The abbot of this nunnery is Khenmo Drolma, an American woman, who is the first "Bhiksunni," a fully ordained Buddhist nun, in the Drikung Kagyu tradition of Buddhism. She is also the first westerner, male or female, to be installed as an abbot.[6]

Christianity

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity and gender |

|---|

|

Within Christianity, women historically have been prevented from being ordained to ministerial positions (such as pastor) on the basis of certain New Testament scriptures often interpreted as prohibitions of female ordination. Prominent among them is the way 1 Timothy 2:12 ("I suffer not a woman") is translated in the King James Version of the New Testament.

Catholic Church

The official position of the Catholic Church, as expressed in the current canon law and the Catechism of the Catholic Church, is that: "Only a baptized man (In Latin, vir) validly receives sacred ordination."[7] Insofar as priestly and episcopal ordination are concerned, the Church teaches that this requirement is a matter of divine law, and thus doctrinal.[8] The requirement that only males can receive ordination to the permanent diaconate has not been promulgated as doctrinal by the Church's magisterium, though it is clearly at least a requirement according to canon law.[9][10]

In opposition the church's official teaching, a number of scholars in the Catholic Church have written in favor of ordaining women.[11]

Orthodox Churches

The Orthodox Churches follows a similar line of reasoning as the Catholic Church with respect to ordination of priests.

Professor Evangelos Theodorou argued that female deacons were actually ordained in antiquity.[12] K. K. Fitzgerald has followed and amplified Professor Theodorou's research. Bishop Kallistos Ware wrote:[13]

The order of deaconesses seems definitely to have been considered an "ordained" ministry during early centuries in at any rate the Christian East. ... Some Orthodox writers regard deaconesses as having been a "lay" ministry. There are strong reasons for rejecting this view. In the Byzantine rite the liturgical office for the laying-on of hands for the deaconess is exactly parallel to that for the deacon; and so on the principle lex orandi, lex credendi—the Church's worshipping practice is a sure indication of its faith—it follows that the deaconesses receives, as does the deacon, a genuine sacramental ordination: not just a [χειροθεσια] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (chirothesia) but a [χειροτονια] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (chirotonia). However, the ordination of women in the Catholic Church does exist. Although it is not widespread, it is official by the Roman Catholic Church.

Even though Bishop Kallistos says this, the Roman Catholic Church has made it clear it will not ordain women to any canonical position such as priest, deacon, or bishop. On October 8, 2004, the Holy Synod of the Orthodox Church of Greece voted to permit the ordination of monastic women deacons, that is, women deacons to minister and assist at the liturgy within their own monasteries.[14][15]

There is a strong monastic tradition, pursued by both men and women in the Orthodox churches, where monks and nuns lead identical spiritual lives. Unlike Western-rite Catholic religious life, which has myriad traditions, both contemplative and active (see Benedictine monks, Franciscan friars, Jesuits), that of Orthodoxy has remained exclusively ascetic and monastic.

Anglicanism

Within Anglicanism, the majority of Anglican provinces ordain women as deacons and priests. Only a few provinces, however, have consecrated women as bishops (although the number of provinces where women bishops are canonically possible is much greater). The Episcopal Church in the United States ordains women as deacons, priests and bishops. In England the issue of women being ordained as bishops is contentious and under discussion.[16]

Protestantism

A key theological doctrine for Reformed and most other Protestants is the priesthood of all believers—a doctrine considered by them so important that it has been dubbed by some as "a clarion truth of Scripture."

This doctrine restores true dignity and true integrity to all believers since it teaches that all believers are priests and that as priests, they are to serve God—no matter what legitimate vocation they pursue. Thus, there is no vocation that is more "sacred" than any other. Because Christ is Lord over all areas of life, and because His word applies to all areas of life, nowhere does His Word even remotely suggest that the ministry is "sacred" while all other vocations are "secular." Scripture knows no sacred-secular distinction. All of life belongs to God. All of life is sacred. All believers are priests.

— Hagopian, David. "Trading Places: The Priesthood of All Believers."[17]

However, most (although not all) Protestant denominations still ordain church leaders who have the task of equipping all believers in their Christian service.Eph. 4:11–13 These leaders (variously styled elders, pastors or ministers) are seen to have a distinct role in teaching, pastoral leadership and the administration of sacraments. Traditionally these roles were male preserves, but over the last century an increasing number of denominations have begun ordaining women. The Church of England appointed female lay readers during the First World War. Later the United Church of Canada in 1936 and the American United Methodist Church in 1956 also began ordained women. Meanwhile, women's ministry has been part of Methodist tradition in Britain for over 200 years. John Wesley allowed women to preach and female ministers existed in the Primitive Methodist Church.

Jehovah's Witnesses

Jehovah's Witnesses consider qualified public baptism to represent the baptizand's ordination, following which he or she is immediately considered an ordained minister. In 1941, the Supreme Court of Vermont recognized the validity of this ordination for a female Jehovah's Witness minister.[18]

Nevertheless, Witness deacons ("ministerial servants") and elders must be male, and only a baptized adult male may perform a Jehovah's Witness baptism, funeral, or wedding.[19] Within the congregation, a female Witness minister may only lead prayer and teaching when there is a special need, and must do so wearing a head covering.[20][21][22]

Islam

Although Muslims do not formally ordain religious leaders, the imam serves as a spiritual leader and religious authority. There is a current controversy among Muslims on the circumstances in which women may act as imams—that is, lead a congregation in salat (prayer). Three of the four Sunni schools, as well as many Shia, agree that a woman may lead a congregation consisting of women alone in prayer, although the Maliki school does not allow this. According to all currently existing traditional schools of Islam, a woman cannot lead a mixed gender congregation in salat (prayer). Some schools make exceptions for Tarawih (optional Ramadan prayers) or for a congregation consisting only of close relatives. Certain medieval scholars—including Al-Tabari (838–932), Abu Thawr (764–854), Al-Muzani (791–878), and Ibn Arabi (1165–1240)—considered the practice permissible at least for optional (nafila) prayers; however, their views are not accepted by any major surviving group.

On March 18th, 2005, an American woman named Amina Wadud (an Islamic studies professor at Virginia Commonwealth University) gave a sermon and led Friday prayers for a Muslim congregation consisting of men as well as women, with no curtain dividing the men and women.[23] Another woman sounded the call to prayer at that same event. This was done in the Synod House of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York after mosques refused to host the event.

Judaism

Only men can become rabbis in Orthodox Judaism, but all other types of Judaism allow and have female rabbis. In 1935 Regina Jonas was ordained privately by a German rabbi and became the world's first female rabbi [76]. Sally Priesand became the first female rabbi in Reform Judaism in 1972,[24] Sandy Eisenberg Sasso became the first female rabbi in Reconstructionist Judaism in 1974,[25] Lynn Gottlieb became the first female rabbi in Jewish Renewal in 1981,[26] Amy Eilberg became the first female rabbi in Conservative Judaism in 1985,[27] and Tamara Kolton became the very first rabbi of either gender (and therefore, since she was female, the first female rabbi) in Humanistic Judaism in 1999.[28] Women in these types of Judaism are routinely granted semicha on an equal basis with men.

Only men can become cantors in Orthodox Judaism, but all other types of Judaism allow and have female cantors. Barbara Ostfeld-Horowitz became the first female cantor in Reform Judaism in 1975.[29] Erica Lipitz and Marla Rosenfeld Barugel became the first female cantors in Conservative Judaism in 1987.[29] The Cantors Assembly, a professional organization of cantors associated with Conservative Judaism, did not allow women to join until 1990[30] Sharon Hordes became the first cantor of either gender (and therefore, since she was female, the first female cantor) in Reconstructionist Judaism in 2002.[31] Avitall Gerstetter, who lives in Germany, became the first female cantor in Jewish Renewal in 2002. Susan Wehle became the first American female cantor in Jewish Renewal in 2004; however, she died in 2009.[32][33] Three female Jewish Renewal cantors have been ordained after Susan Wehle's ordination—a German woman (born in Holland), Yalda Rebling, was ordained in 2007,[34] an American woman, Michal Rubin, was ordained in 2010, and an American woman, Abbe Lyons, was ordained in 2010.[35] In 2001 Deborah Davis became the first cantor of either gender (and therefore, since she was female, the first female cantor) in Humanistic Judaism; however, Humanistic Judaism has since stopped graduating cantors.[36]

Shinto

While the priesthood was traditionally male in Shinto, ordination of women as Shinto priests has arisen after the abolition of State Shinto in the aftermath of World War II.[37]

Tenrikyo

The religion of Tenrikyo was founded by a woman, Oyasama.[38]

Some beginning dates for ordination of women

This section needs expansion with: decisions against women's ordination to balance the list. You can help by adding to it. (June 2008) |

A list with dates of important events in the history of women's ordination appears below:[39]

- 1553: The Church of England first consecrated a woman when Queen Mary I was consecrated Head of the Church of England.

- circa 1770: Mary Evans Thorne was appointed class leader by Joseph Pilmore in Philadelphia, probably the first woman in America to be so appointed.[40]

- late 1700s: John Wesley allowed women to preach within his Methodist wing of the Church of England.

- Early 1800s: A fundamental belief[41] of the Society of Friends (Quakers) has always been the existence of an element of God's spirit in every human soul. Thus all persons are considered to have inherent and equal worth, independent of their gender. This led naturally to an acceptance of female ministers. In 1660, Margaret Fell (1614–1702) published a famous pamphlet to justify equal roles for men and women in the denomination. It was titled: "Women's Speaking Justified, Proved and Allowed of by the Scriptures, All Such as Speak by the Spirit and Power of the Lord Jesus And How Women Were the First That Preached the Tidings of the Resurrection of Jesus, and Were Sent by Christ's Own Command Before He Ascended to the Father (John 20:17)." In the U.S., in contrast with almost every other organized religion, the Society of Friends (Quakers) has allowed women to serve as ministers since the early 1800s.

- 1807: The Primitive Methodist Church in Britain first allowed female ministers.

- 1815: Clarissa Danforth was ordained in New England. She was the first woman ordained by the Free Will Baptist denomination.

- 1853: Antoinette Brown Blackwell was the first woman ordained by a church belonging to the Congregationalist Church.[42] However, her ordination was not recognized by the denomination. She quit the church and later became a Unitarian. The Congregationalists later merged with others to create the United Church of Christ, which ordains women.

- 1861: Mary A. Will was the first woman ordained in the Wesleyan Methodist Connection by the Illinois Conference in the USA. The Wesleyan Methodist Connection eventually became The Wesleyan Church.

- 1863: Olympia Brown was ordained by the Universalist denomination in 1863, the first woman ordained by that denomination, in spite of a last-moment case of cold feet by her seminary which feared adverse publicity.[43] After a decade and a half of service as a full-time minister, she became a part-time minister in order to devote more time to the fight for women's rights and universal suffrage. In 1961, the Universalists and Unitarians joined to form the Unitarian Universalist Association (UUA).[44] The UUA became the first large denomination to have a majority of female ministers.[45]

- 1865: The Salvation Army was founded, which in the English Methodist tradition always ordained both men and women. However, there were initially rules that prohibited a woman from marrying a man who had a lower rank.

- 1866: Helenor M. Davison was ordained as a deacon by the North Indiana Conference of the Methodist Protestant Church, probably making her the first ordained woman in the Methodist tradition.[46]

- 1869: Margaret Newton Van Cott became the first woman in the Methodist Episcopal Church to receive a local preacher's license.

- 1869: Lydia Sexton (of the United Brethren Church) was appointed chaplain of the Kansas State Prison at the age of 70, the first woman in the United States to hold such a position.[47]

- 1876: Anna Oliver was the first woman to receive the Bachelor of Divinity degree from an American seminary (Boston University School of Theology).[48]

- 1879 The Church of Christ, Scientist was founded by a woman, Mary Baker Eddy.[49]

- 1880: Anna Howard Shaw was the first woman ordained in the American Methodist Protestant Church, which later merged with other denominations to form the United Methodist Church.[50]

- 1888: Fidelia Gillette may have been the first ordained woman in Canada. She served the Universalist congregation in Bloomfield, Ontario, during 1888 and 1889. She was presumably ordained in 1888 or earlier.[original research?]

- 1889: The Nolin Presbytery of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church ordained Louisa Woosley as the first female minister of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church, USA.[51]

- 1889: Ella Niswonger was the first woman ordained in the American United Brethren Church, which later merged with other denominations to form the American United Methodist Church.[52]

- 1892: Anna Hanscombe is believed to be the first woman ordained by the parent bodies which formed the Church of the Nazarene in 1919.

- 1894: Julia A. J. Foote was the first woman to be ordained as a deacon by the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church [77].

- 1909: The Church of God (Cleveland TN) began ordaining women in 1909.

- 1911: Ann Allebach was the first Mennonite woman to be ordained. This occurred at the First Mennonite Church of Philadelphia.

- 1914: The Assemblies of God was founded and ordained its first woman clergy in 1914.

- 1917: The Church of England appointed female Bishop's Messengers to preach, teach, and take missions in the absence of men.

- 1917: The Congregationalist Church (England and Wales) ordained their first woman, Constance Coltman (née Todd) at the King's Weigh House, London. Its successor is the United Reformed Church (a union of the Congregational Church in England and Wales and the Presbyterian Church of England in 1972. Since then two more denominations have joined the union: The Reformed Churches of Christ (1982) and the Congregational Church of Scotland (2000). All of these denominations ordained women at the time of Union and continue to do so. The first woman to be appointed General Secretary of the United Reformed Church was Roberta Rominger in 2008.

- 1920: The Methodist Episcopal Church granted women the right to become licensed as local preachers.[53]

- 1920's: Some Baptist denominations started ordaining women.

- 1922: The Jewish Reform movement's Central Conference of American Rabbis stated that "...woman cannot justly be denied the privilege of ordination."[54]

- 1922: The Annual Conference of the Church of the Brethren granted women the right to be licensed into the ministry, but not to be ordained with the same status as men.

- 1924: The Methodist Episcopal Church granted women limited clergy rights as local elders or deacons, without conference membership.[55]

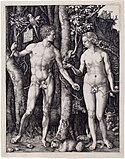

- 1929: Izabela Wiłucka-Kowalska was the first woman to be ordained by the Old Catholic Mariavite Church in Poland.

- 1935: Regina Jonas was ordained privately by a German rabbi and became the world's first female rabbi.[56]

- 1936: Lydia Gruchy became the first female minister in the United Church of Canada.[57]

- 1944: Florence Li Tim Oi became the first woman to be ordained as an Anglican priest. She was born in Hong Kong, and was ordained in Guandong province in unoccupied China on January 25, 1944, on account of a severe shortage of priests due to World War II. When the war ended, she was forced to relinquish her priesthood, yet she was reinstated as a priest later in 1984 in Toronto.[58] [59]

- 1947: The Czechoslovak Hussite Church started to ordain women.

- 1948: The Evangelical Lutheran Church of Denmark started to ordain women.

- 1949: The Old Catholic Church (in the U.S.) started to ordain women.

- 1952: The Church of England consecrated Queen Elizabeth II as Head of the Church of England.

- 1956: Maud K. Jensen was the first woman to receive full clergy rights and conference membership (in her case, in the Central Pennsylvania Conference) in the Methodist Church[60]

- 1956: The Presbyterian Church (USA) ordained its first female minister, Margaret Towner.[61]

- 1958: Women ministers in the Church of the Brethren were given full ordination with the same status as men.

- 1959: The Reverend Gusta A. Robinette, a missionary, was ordained in the Sumatra (Indonesia) Conference soon after The Methodist Church granted full clergy rights to women in 1956. She was appointed District Superintendent of the Medan Chinese District in Indonesia becoming the first female district superintendent in the Methodist Church.[62]

- 1960: The Evangelical Lutheran Church of Sweden started ordaining women.

- 1964: Addie Davis became the first Southern Baptist woman to be ordained.[63] However, the Southern Baptist Convention stopped ordaining women in 2000, although existing female pastors are allowed to continue their jobs.[64]

- 1967: The Presbyterian Church in Canada started ordaining women.

- 1967: Margaret Henrichsen became the first American female district superintendent in the Methodist Church.[65]

- 1970: On November 22, 1970, Elizabeth Alvina Platz became the first woman ordained by the Lutheran Church in America, and as such was the first woman ordained by any Lutheran denomination in America.[66] The first woman ordained by the American Lutheran Church, Barbara Andrews, was ordained in December 1970.[67] (The first woman ordained by the Association of Evangelical Lutheran Churches, Janith Otte, was ordained in 1977.[68]

- 1971: Anglican communion, Hong Kong. Joyce Bennett and Jane Hwang were the first regularly ordained priests.

- 1972: Freda Smith became the first female minister to be ordained by the Metropolitan Community Church[69]

- 1972: Sally Priesand became the first female rabbi to be ordained in Reform Judaism, and also the first female rabbi in the world to be ordained by any theological seminary.[70]

- 1974: The Methodist Church in the United Kingdom started to ordain women again (after a lapse of ordinations.)

- 1974: Sandy Eisenberg Sasso became the first female rabbi to be ordained in Reconstructionist Judaism.[71]

- 1975: Dorothea W. Harvey became the first woman to be ordained by the Swedenborgian Church.[72]

- 1975: Barbara Ostfeld-Horowitz became the first female cantor in Reform Judaism [29]

- 1976: The Anglican Church in Canada ordained six female priests.

- 1976: The Rev. Pamela McGee was the first female ordained to the Lutheran ministry in Canada.

- 1977: The Anglican Church of New Zealand ordained five female priests.

- 1977: The first woman ordained by the Association of Evangelical Lutheran Churches, Janith Otte, was ordained in 1977.[73]

- 1977: On January 1, 1977, Jacqueline Means became the first woman ordained to the priesthood in the Episcopal Church [78]. 11 women were "irregularly" ordained to the priesthood in Philadelphia on July 29, 1974, before church laws were changed to permit women's ordination.[74] They are often called the "Philadelphia 11." Church laws were changed on September 16, 1976.[75]

- 1979: The Reformed Church in America started ordaining women as ministers [79]. Women had been admitted to the offices of deacon and elder in 1972.

- 1980: Marjorie Matthews, at the age of 64, was the first woman elected as a bishop in the United Methodist Church.[76]

- 1981: Lynn Gottlieb became the first female rabbi to be ordained in the Jewish Renewal movement.[77]

- 1983: An Anglican woman was ordained in Kenya.

- 1983: Three Anglican women were ordained in Uganda.

- 1984: The Community of Christ (known at the time as the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints) authorized the ordination of women. This is the second largest Latter Day Saint denomination.

- 1985: According to the New York Times for 1985-FEB-14: "After years of debate, the worldwide governing body of Conservative Judaism has decided to admit women as rabbis. The group, the Rabbinical Assembly, plans to announce its decision at a news conference...at the Jewish Theological Seminary..." In 1985 Amy Eilberg became the first female rabbi to be ordained in Conservative Judaism.[78]

- 1985: The first women deacons were ordained by the Scottish Episcopal Church.

- 1987: Erica Lipitz and Marla Rosenfeld Barugel became the first female cantors in Conservative Judaism.[29]

- 1988: The Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland started to ordain women.

- 1988: The Episcopal Church elected Barbara Harris as its first female bishop.[79]

- 1990: Anglican women were ordained in Ireland.

- 1992: In November 1992 the General Synod of the Church of England approved the ordination of women as priests.[80]

- 1992: The Anglican Church of South Africa started to ordain women.

- 1994: The first women priests were ordained by the Scottish Episcopal Church.

- 1994: On March 12, 1994, the Church of England ordained 32 women as its first female priests.[81]

- 1995: Sligo Seventh-day Adventist Church in Takoma Park, MD, ordained three women in violation of the denomination's rules - Kendra Haloviak, Norma Osborn, and Penny Shell.[82]

- 1995: The Christian Reformed Church voted to allow congregations and regional church bodies called "classes" to permit the ordination of women ministers, elders, deacons, and/or ministry associates if they wished to do so. In 1998-NOV, the North American Presbyterian and Reformed Council (NAPARC) suspended the CRC's membership because of this decision.

- 1998: The General Assembly of the Nippon Sei Ko Kai (Anglican Church in Japan) started to ordain women.

- 1998: The Guatemalan Presbyterian Synod started to ordain women.

- 1998: The Old Catholic Church in the Netherlands started to ordain women.

- 1998: Some Orthodox Jewish congregations started to employ women as congregational interns, a job created for learned Orthodox Jewish women. Although these interns do not lead worship services, they perform some tasks usually reserved for rabbis, such as preaching, teaching, and consulting on Jewish legal matters. The first woman hired as a congregational intern was Julie Stern Joseph, hired in 1998 by the Lincoln Square Synagogue of the Upper West Side.[83]

- 1999: The Independent Presbyterian Church of Brazil allowed the ordination of women as either clergy or elders.

- 1999: Tamara Kolton became the first rabbi of either sex (and therefore, because she was female, the first female rabbi) to be ordained in Humanistic Judaism.[84]

- 2000: The Baptist Union of Scotland voted to allow their individual churches to make local decisions as to whether to allow or prohibit the ordination of women.

- 2000: In July 2000 Vashti McKenzie was elected as the first female bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church.[85]

- 2000: The Mombasa diocese of the Anglican Church of Kenya began to ordain women. [vague]

- 2000: The Church of Pakistan ordained its first female deacons.

- 2001: Deborah Davis became the first cantor of either sex (and therefore, since she was female, the first female cantor) in Humanistic Judaism; however, Humanistic Judaism has since stopped graduating cantors.[86]

- 2002: Sharon Hordes became the very first cantor in Reconstructionist Judaism. Therefore, since she was a woman, she became their first female cantor).[87]

- 2002: Avitall Gerstetter, who lives in Germany, became the first female cantor in Jewish Renewal.

- 2004: Susan Wehle became the first American female cantor in Jewish Renewal in 2004 [80].

- 2005: The Lutheran Evangelical Protestant Church, (LEPC) (GCEPC) in the USA elected Nancy Kinard Drew as its first female Presiding Bishop.

- 2006: The Episcopal Church elected Katharine Jefferts Schori as its first female Presiding Bishop, or Primate.[88]

- 2007: The synod of the Christian Reformed Church voted 112-70 to allow any Christian Reformed Church congregation that wishes to do so to ordain women as ministers, elders, deacons and/or ministry associates; since 1995, congregations and regional church bodies called "classes" already had the option of ordaining women, and 26 of the 47 classes had exercised it before the vote in June.[89]

- 2008: Mildred "Bonnie" Hines was elected as the first female bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church.[90]

- 2009: The Evangelical Church in Germany (EKD) elected Margot Käßmann as its first female Presiding Bishop, or Primate.

- 2009: Alysa Stanton became the world's first African-American female rabbi.[91]

- 2010: The Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland elected Irja Askola of the Diocese of Helsinki as its first female bishop.[92]

See also

- Christian views of women

- Deaconess

- Episcopa Theodora

- Feminist theology

- List of the first 32 women ordained as Church of England priests

- List of women priests

- Mariavite Church

- Women as theological figures

- Women in the Bible

Further reading

- Canon Law Society of America. The Canonical Implications of Ordaining Women to the Permanent Diaconate, 1995. ISBN 0-943616-71-9.

- Davies, J. G. "Deacons, Deaconesses, and Minor Orders in the Patristic Period," Journal of Ecclesiastical History, 1963, v. 14, p. 1-23.

- Elsen, Ute E. Women Officeholders in Early Christianity: Epigraphical and Literary Studies, Liturgical Press, 2000. ISBN 0-8146-5950-0.

- Grudem, Wayne. Evangelical Feminism and Biblical Truth: An Analysis of Over 100 Disputed Questions, Multnomah Press, 2004. 1-57673-840-X.

- Gryson, Roger. The Ministry of Women in the Early Church, Liturgical Press, 1976. ISBN 0-8146-0899-X. Translation of: Le ministère des femmes dans l'Église ancienne, J. Duculot, 1972.

- LaPorte, Jean. The Role of Women in Early Christianity, Edwin Mellen Press, 1982. ISBN 0-88946-549-5.

- Madigan, Kevin, and Carolyn Osiek. Ordained Women in the Early Church: A Documentary History, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-8018-7932-9.

- Martimort, Aimé Georges, Deaconesses: An Historical Study, Ignatius Press, 1986, ISBN 0-89870-114-7. Translation of: Les Diaconesses: Essai Historique, Edizioni Liturgiche, 1982.

- Miller, Patricia Cox. Women in Early Christianity: Translations from Greek Texts, Catholic University of America Press, 2005. ISBN 0-8132-1417-3.

- Weaver, Mary Jo. New Catholic Women, Harper and Row, 1985, 1986. ISBN 0-253-20993-5.

- Wijngaards, John, The Ordination of Women in the Catholic Church. Unmasking a Cuckoo's Egg Tradition, Darton, Longman & Todd, 2001. ISBN ISBN 0-232-52420-3; Continuum, New York, 2001. ISBN 0-8264-1339-0.[93]

- Wijngaards, John. Women Deacons in the Early Church: Historical Texts and Contemporary Debates, Herder & Herder, 2002, 2006. ISBN 0-8245-2393-8.[94]

- Zagano, Phyllis. Holy Saturday: An Argument for the Restoration of the Female Diaconate in the Catholic Church, Herder & Herder, 2000. ISBN 978-0-8245-1832-5.

- Zagano, Phyllis. "Catholic Women Deacons: Present Tense," Worship 77:5 (September 2003) 386-408.

References

- ^ "The question of the ordination of women in the community of churches." Anglican Theological Review, Viser, Jan. Summer 2002 Accessed: 09-18-2007

- ^ a b c d Thinking About Women's Ordination Wheaton Univ. Women's Review.

- ^ Macmillan Encyclopedia of Buddhism (Volume One), page 352

- ^ Book of the Discipline, Pali Text Society, volume V, Chapter X

- ^ [1]

- ^ [2]

- ^ Codex Iruis Canonici canon 1024, c.f. Catechism of the Catholic Church 1577

- ^ "The Catholic Church has never felt that priestly or episcopal ordination can be validly conferred on women," Inter Insigniores, October 15, 1976, section 1

- ^ Canonical Implications of Ordaining Women to the Permanent Diaconate, Canon Law Society of America, 1995.

- ^ Commentary by the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith on the Declaration Inter Insigniores.

- ^ [3]

- ^ Orthodox Women and Pastoral Praxis | The St. Nina Quarterly

- ^ "Man, Woman and the Priesthood of Christ," in Women and the Priesthood, ed. T. Hopko (New York, 1982, reprinted 1999), 16, as quoted in Women Deacons in the Early Church, by John Wijngaards, ISBN 0–8245–2393–8.

- ^ America | The National Catholic Weekly--‘Grant Her Your Spirit’

- ^ http://www.orthodoxwomen.org/files/SCOBA_Women_Deacons.pdf

- ^ http://www.catholicculture.org/news/headlines/index.cfm?storyid=6268

- ^ Hagopian, David. "Trading Places: The Priesthood of All Believers." Web: 10 Jul 2010.

- ^ "Women—May They Be “Ministers”?", The Watchtower, March 15, 1981, page 19, "Several courts in the United States have recognized female Jehovah’s Witnesses, in carrying on the door-to-door evangelistic work, as ministers. For example, the Supreme Court of Vermont, in Vermont v. Greaves (1941), stated that Elva Greaves “is an ordained minister of a sect or class known and designated as ‘Jehovah’s Witnesses’.”"

- ^ "Applying the General Priesthood Principle", The Watchtower, February 1, 1964, page 86, "Among the witnesses of Jehovah any adult, dedicated and baptized male Christian who is qualified may serve in such ministerial capacities as giving public Bible discourses and funeral talks, performing marriages and presiding at the Lord’s evening meal or supper. There is no clergy class."

- ^ "Head Coverings—When and Why?", Keep Yourselves in God's Love, ©2008 Watch Tower, page 210-211, "Occasionally, though, circumstances may require that a Christian woman be called on to handle a duty normally performed by a qualified baptized male. For instance, she may need to conduct a meeting for field service because a qualified baptized male is not available or present. ..she would wear a head covering to acknowledge that she is handling the duty normally assigned to a male. On the other hand, many aspects of worship do not call for a sister to wear a head covering. For example, she does not need to do so when commenting at Christian meetings, engaging in the door-to-door ministry with her husband or another baptized male, or studying or praying with her unbaptized children."

- ^ "Questions From Readers", The Watchtower, July 15, 2002, page 27, "There may be other occasions when no baptized males are present at a congregation meeting. If a sister has to handle duties usually performed by a brother at a congregationally arranged meeting or meeting for field service, she should wear a head covering."

- ^ "Woman’s Regard for Headship—How Demonstrated?", The Watchtower, July 15, 1972, page 447, "At times no baptized male Witnesses may be present at a congregational meeting (usually in small congregations or groups). This would make it necessary for a baptized female Witness to pray or preside at the meeting. Recognizing that she is doing something that would usually be handled by a man, she would wear a head covering."

- ^ [4]

- ^ [5]

- ^ [6]

- ^ [7]

- ^ [8]

- ^ [9]

- ^ a b c d [10] Cite error: The named reference "jwa.org" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ [11]

- ^ [12]

- ^ [13].

- ^ [14]

- ^ [15]

- ^ [16]

- ^ [17]

- ^ Encyclopedia of Shinto—Home : Shrine Rituals : Gyōji sahō

- ^ "Religious Movements Homepage: Tenrikyo". Retrieved 2007–03–20.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ When churches started to ordain women

- ^ [18]

- ^ Religious Tolerance.org on Quakers

- ^ [19]

- ^ [20]

- ^ Unitarian Universalism

- ^ [21]

- ^ [22]

- ^ [23]

- ^ [24]

- ^ [25]

- ^ [26]

- ^ [27]

- ^ [28].

- ^ [29]

- ^ [30]" However, the first woman in Reform Judaism to be ordained (Sally Priesand) was not ordained until 1972 [31]

- ^ [32]

- ^ [33].

- ^ [34]

- ^ [35]

- ^ [36]

- ^ [37]

- ^ [38]

- ^ [39]

- ^ [40]

- ^ [41]

- ^ [42]

- ^ [43]

- ^ [44]. On January 1, 1988 the Lutheran Church in America, the American Lutheran Church, and the Association of Evangelical Lutheran Churches merged to form the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, which continues to ordain women [45]

- ^ [46]

- ^ [47]

- ^ [48]

- ^ [49]

- ^ [50]

- ^ [51]

- ^ [52]

- ^ [53]

- ^ [54] [55]

- ^ [56]

- ^ [57]

- ^ [58]

- ^ [59]

- ^ [60]

- ^ [61]

- ^ [62]

- ^ [63]

- ^ [64]

- ^ [65]

- ^ [66]

- ^ [67]

- ^ [68]

- ^ [69]

- ^ [70]

- ^ [71]

- ^ [72]

- ^ [73]

External links

- American Fellowship Church - (Ordains Women currently)

- episcopa—women bishops Photo blog about women bishops in Christian churches.

- http://www.romancatholicwomenpriests.org/

- http://www.womenpriests.org.

- Sarah Sentilles [81]—a doctoral candidate in theology at Harvard and author of A Church of Her Own: What Happens When a Woman Takes the Pulpit (Harcourt, 2008) which addresses the struggles and triumphs of women who respond to the call to ministry. See also Tavis Smiley interview with Sarah Sentilles

- The Right Reverend Eric Kemp - Daily Telegraph obituary

- Women as Clergy: When some faith groups started to ordain women—including many Christian and Jewish Faith Groups. — 'For' ordination of women.

Buddhist

- "1st International Congress on Buddhist Women's Role in the Sangha: Bhikshuni Vinaya and Ordination Lineages," Hamburg 2007

- Challenge to Thai Sangha's ban on women—Christian Science monitor

- Ordination of women—Buddhism

Christian

Anglican/Episcopal Permitted

Anglican/Episcopal Prohibited

- Affirmation of St Louis (1977) - Document was partly the result of the Episcopal Church USA decision to ordain women.

- The Anglican Catholic Church

- The Anglican Province of America

- The United Episcopal Church of North America

- Forward in Faith - Traditional Anglicans in the Diocese of Lincoln

- Priestesses in the Church?—Article on the ordination of women by C. S. Lewis

Non-Denominational Permitted

Evangelical Permitted

- Christians for Biblical Equality—Egalitarian Evangelical perspective on gender issues

- Can Women Preach? by James H. Boyd

Evangelical Prohibited

- Council of Biblical Manhood and Womanhood—Complementarian Evangelical perspective on gender issues

- Evangelical Feminism and Biblical Truth: An Analysis of Over 100 Disputed Questions pdf by Wayne Grudem of CBMW

- (See also Presbyterian churches—Prohibited, below)

Presbyterian churches Permitted

- Women Elders—From a Presbyterian Church (USA) site

- Celebrating the anniversary of the recognition of women's call to ordained ministry

Presbyterian churches Prohibited

- "Report of the Committee on Hermeneutics of Women in Ordained Office" submitted to the 54th GA of the Orthodox Presbyterian Church (1987) (.html)

- "Report on Women in Office" submitted to the 55th GA of the Orthodox Presbyterian Church (1988) (.html)

- Position Paper Approved by the General Synod of the Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church (.pdf)

- Rev. Rich Lusk, "Ministry, Women, and Liturgy," May 2000 (.pdf)

- Rev. James B. Jordan, "Liturgical Man, Liturgical Woman (Part 1)," Rite Reasons No. 86, May 2004 (.htm)

- Rev. James B. Jordan, "Liturgical Man, Liturgical Woman (Part 2)," Rite Reasons No. 87, June 2004 (.htm)

Roman Catholic Permitted

- Womenpriests.org Website advocating the ordination of women to the Roman Catholic priesthood. This website sets out both sides of the argument and provides all Vatican documents about women's ordination.

- Http://www.womenpriests.org/circles/[82] is an international discussion board about the case for women's ordination

- Phyllis Zagano, "Grant Her Your Spirit"—America, Vol. 192 No. 4, February 7, 2005.

Roman Catholic Prohibited

- Forward in Faith—Anglo-Catholic Anglicans in Opposition to Women in the Priesthood

Eastern Orthodox Permitted

- Valerie A. Karras, "Women in the Eastern Church"—St. Nina Quarterly, v. 1, n. 1.

- Teva Regule, "An Interview with Bishop Kallistos Ware"—St. Nina Quarterly, v. 1, n. 3.

- Kyriaki Karidoyanes FitzGerald, "Orthodox Women and Pastoral Praxis"—St. Nina Quarterly, v. 3, n. 2.

Eastern Orthodox Prohibited

- "How Not to Read the Fathers: In Response to Ms. Karras"—Archbishop Chrysostomos, from Orthodox Tradition, Vol. XIII, No. 2, pp. 10–12.

- "What Beef Have Women Theologians with Divine Order? Orthodox Theologies of Women and Ordained Ministry"—Rebecca Herman