Christ Church, Oxford

| Christ Church | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| University of Oxford | ||||||||||||

The Great Quadrangle | ||||||||||||

Arms: Sable, on a cross engrailed argent, a lion passant gules, between four leopards' faces azure, on a chief or, a rose gules barbed and seeded proper, between two Cornish choughs sable, beaked and membered gules. | ||||||||||||

| Location | St Aldate's, Oxford, OX1 1DP | |||||||||||

| Coordinates | 51°45′01″N 1°15′21″W / 51.750199°N 1.255853°W | |||||||||||

| Full name | The Dean and Chapter of the Cathedral Church of Christ in Oxford of the Foundation of King Henry the Eighth | |||||||||||

| Latin name | Ædes Christi/Ecclesia Christi Cathedralis Oxon: ex fundatione Regis Henrici Octavi[1] | |||||||||||

| Established | 1546 | |||||||||||

| Named for | Jesus Christ | |||||||||||

| Sister college | Trinity College, Cambridge | |||||||||||

| Dean | Sarah Foot | |||||||||||

| Undergraduates | 432[2] (2017/2018) | |||||||||||

| Postgraduates | 196 | |||||||||||

| Endowment | £769.8 million (2022)[3] | |||||||||||

| Visitor | ||||||||||||

| Website | www | |||||||||||

| Boat club | Christ Church Boat Club | |||||||||||

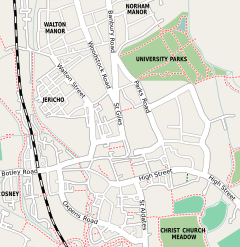

| Map | ||||||||||||

Christ Church (Latin: Ædes Christi, the temple or house, ædes, of Christ, and thus sometimes known as "The House") is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England.[4] Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, the college is uniquely a joint foundation of the university and the cathedral of the Oxford diocese, Christ Church Cathedral, which also serves as the college chapel and whose dean is ex officio the college head.

As of 2022, Christ Church had the largest financial endowment of any Oxford college at £770 million.[5] As of 2022, the college had 661 students.[4] Its grounds contain a number of architecturally significant buildings including Tom Tower (designed by Sir Christopher Wren), Tom Quad (the largest quadrangle in Oxford), and the Great Dining Hall, which was the seat of the parliament assembled by King Charles I during the English Civil War. The buildings have inspired replicas throughout the world in addition to being featured in films such as Harry Potter and The Golden Compass, helping Christ Church become the most popular Oxford college for tourists with almost half a million visitors annually.[6]

The college's alumni include 13 British prime ministers (the highest number of any Oxbridge college), as well as former prime ministers of Pakistan and Ceylon. Other notable alumni include King Edward VII, King William II of the Netherlands, William Penn, writers Lewis Carroll (author of Alice in Wonderland) and W. H. Auden, philosopher John Locke, and scientist Robert Hooke. Two Nobel laureates, Martin Ryle and John Gurdon, studied at Christ Church.[7] Albert Einstein is also associated with the college. The college has several cities and places named after it.[8]

History

[edit]

In 1525, at the height of his power, Thomas Wolsey, Lord Chancellor of England and Cardinal Archbishop of York, suppressed St Frideswide's Priory in Oxford and founded Cardinal College on its lands, using funds from the dissolution of Wallingford Priory and other minor priories.[9] He planned the establishment on a magnificent scale, but fell from grace in 1529, with the buildings only three-quarters complete, as they were to remain for 140 years.[citation needed]

In 1531 the college was itself suppressed, but it was refounded in 1532 as King Henry VIII's College by Henry VIII, to whom Wolsey's property had escheated. Then in 1546 the King, who had broken from the Church of Rome and acquired great wealth through the dissolution of the monasteries in England, refounded the college as Christ Church as part of the reorganisation of the Church of England, making the partially demolished priory church the cathedral of the recently created Diocese of Oxford.[citation needed]

Christ Church's sister college in the University of Cambridge is Trinity College, Cambridge, founded the same year by Henry VIII. Since the time of Queen Elizabeth I the college has also been associated with Westminster School. The dean remains to this day an ex officio member of the school's governing body.[10][11]

Major additions have been made to the buildings through the centuries, and Wolsey's Great Quadrangle was crowned with the famous gate-tower designed by Christopher Wren. To this day, the bell in the tower, Great Tom, is rung 101 times at 9 pm measured by Oxford time, meaning at 9:05 pm GMT/BST every night, once for each of the 100 original scholars of the college, plus one more stroke added in 1664. In former times this was done at midnight, signalling the close of all college gates throughout Oxford. Since it took 20 minutes to ring the 101, the Christ Church gates, unlike those of other colleges, did not close until 12:20 am. When the ringing was moved back to 9:00 pm, Christ Church gates still remained open until 12.20, 20 minutes later than any other college. Although the clock itself now shows GMT/BST, Christ Church still follows Oxford time in the timings of services in the cathedral.[12]

King Charles I made the Deanery his palace and held his Parliament in the Great Hall during the English Civil War.[13] In the evening of 29 May 1645, during the second siege of Oxford, a "bullet of IX lb. weight" shot from the Parliamentarians' warning-piece at Marston fell against the wall of the north side of the Hall.[14]

Several of Christ Church's deans achieved high academic distinction, notably Owen under the Commonwealth, Aldrich and Fell in the Restoration period, Jackson and Gaisford in the early 19th century and Liddell in the high Victorian era.[citation needed]

For over four centuries Christ Church admitted men only; the first female students at Christ Church matriculated in 1980.[15]

Organisation

[edit]Christ Church, formally titled "The Dean and Chapter of the Cathedral Church of Christ in Oxford of the Foundation of King Henry the Eighth",[1] is the only academic institution in the world which is also a cathedral, the seat (cathedra) of the Bishop of Oxford. The Visitor of Christ Church is the reigning British sovereign[16] (currently King Charles III), and the Bishop of Oxford is unique among English bishops in not being the Visitor of his own cathedral.[citation needed]

The head of the college is the Dean of Christ Church.[17] Christ Church is unique among Oxford colleges in that its Head of House, who is head of both college and cathedral, must be an Anglican cleric appointed by the Crown as dean of the cathedral church. The dean lives on site in a grand 16th-century house in the main quadrangle. The college's activities are managed by a senior and a junior censor (formally titled the Censor Moralis Philosophiae and the Censor Naturalis Philosophiae) the former of whom is responsible for academic matters, the latter for undergraduate discipline. They are chosen from among the members of the governing body. A Censor Theologiae is also appointed to act as the dean's deputy; this post is currently held by Ian Watson.[citation needed]

The form "Christ Church College" is considered incorrect, in part because it ignores the cathedral, an integral part of the unique dual foundation.[citation needed]

Governing body

[edit]The governing body of Christ Church consists of the dean and chapter of the cathedral, together with the "Students of Christ Church", who are not junior members but rather the equivalent of the fellows of the other colleges. Until the later 19th century, the students differed from fellows in that they had no governing powers in their own college, as those resided solely with the dean and chapter. The governing body of Christ Church now has around 60 members. Serving alongside the seven members of chapter, the other members include statutory professors and associate professors with joint appointments (employed both by the University and Christ Church) as well as early-career career development fellows on fixed-term contracts. Sir John Bell and Sir Tim Berners-Lee are both members of the governing body of Christ Church.[18]

Buildings and grounds

[edit]

Christ Church sits in approximately 175 acres (71 hectares) of land.[19] This includes the Christ Church Meadow (including Merton Field and Boathouse Island), which is open to the public all year round. In addition Christ Church own Aston's Eyot (purchased from All Souls College in 1891),[20] Christ Church recreation ground (including the site of Liddell Building), and School Field which has been leased to Magdalen College School since 1893.[21] The meadow itself is inhabited by English Longhorn cattle.[22] In October 1783 James Sadler made the first hot air balloon ascent in Britain from the meadow.[23] The college gardens, quadrangles, and meadow are Grade I listed on the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens.[24]

Christ Church has a number of architecturally significant buildings. These include:

|

Grade I listed:

|

Grade II* listed: Others:

|

Influences

[edit]

The college buildings and grounds are the setting for parts of Evelyn Waugh's Brideshead Revisited, as well as a small part of Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland.[29][30] More recently it has been used in the filming of the movies of J. K. Rowling's Harry Potter series and also the film adaptation of Philip Pullman's novel Northern Lights (the film bearing the title of the American edition of the book, The Golden Compass). Distinctive features of the college's architecture have been used as models by a number of other academic institutions, including the NUI Galway, which reproduces Tom Quad. The University of Chicago, Cornell University, and Kneuterdijk Palace have reproductions of Christ Church's dining hall (in the forms of Hutchinson Hall, the dining hall of Risley Residential College, and the Gothic hall of Kneuterdijk Palace,[31][32] respectively). ChristChurch Cathedral in New Zealand, after which the City of Christchurch is named, is itself named after Christ Church, Oxford. Stained glass windows in the cathedral and other buildings are by the Pre-Raphaelite William Morris group with designs by Edward Burne-Jones.[33][34]

Resident animals on grounds

[edit]Historically, there has been a resident tortoise for the annual Oxford tortoise races.[35] However, since 2020, due to the pandemic, there has not been a tortoise. Recently, there have been two "resident" ducks, which can be seen in Tom Quad, affectionately named "Tom" and "Peck" after two of the famous quadrangles in Christ Church.[36][37]

The Mercury fountain also houses carp, notably a large koi carp named George, which was a gift from the Empress of Japan. A heron may also be frequently seen visiting the pond as their hunting ground. This stopped, in September 2022, when the fishes were moved to a spacious lake home somewhere in Oxfordshire while the College perform essential maintenance on the pond.[38]

Outside the Meadow Building in the Christ Church Meadow, there are also cows present during the day. The cows are of rare English Longhorn breed.[39]

Cathedral choir

[edit]

Long associated with High Church Anglicanism,[40] Christ Church is unique in that it has both a cathedral choir and a college choir. The cathedral choir comprises twelve adults and sixteen boys. The adults are made up of lay clerks and choral scholars, or academical clerks. The choir was all male until 2019, when they welcomed alto Elizabeth Nurse, the first female clerk of Christ Church Cathedral Choir.[41] The boys, whose ages range from eight to thirteen, are chosen for their musical ability and attend Christ Church Cathedral School. Aside from the director, Peter Holder, there is also a sub-organist and two organ scholars. The college choir, however, is always a student-run society, and sings Evensong once a week in term time. In vacations the services are sung by the Cathedral Singers of Christ Church – a choir drawn from semi-professional singers in and around Oxford. The cathedral also hosts visiting choirs from time to time during vacations.[citation needed]

Throughout its history, the cathedral choir has attracted many distinguished composers and organists – from its first director, John Taverner, appointed by Cardinal Wolsey in 1526, to William Walton in the twentieth century. In recent years, the choir have commissioned recorded works by contemporary composers such as John Tavener, William Mathias and Howard Goodall, also patron of Christ Church Music Society.[citation needed]

The choir, which broadcasts regularly, have many recordings to their credit and were the subject of a Channel 4 television documentary Howard Goodall's Great Dates (2002). The documentary was nominated at the Montreux TV Festival in the arts programme category – and has since been seen internationally. The choir's collaboration with Goodall has also led to their singing his TV themes for Mr. Bean and Vicar of Dibley. They appeared in Howard Goodall's Big Bangs, broadcast in the United Kingdom on Channel 4 in March 2000. Treasures of Christ Church (2011) is an example of the choir's recording and debuted as the highest new entry in the UK Specialist Classical chart.[42] The disc featured on BBC Radio 3's In Tune on 26 September 2011 and on Radio 3's Breakfast Show on 27 September that year.[citation needed]

Picture Gallery

[edit]Christ Church holds one of the most important private collections of drawings in the UK, including works by Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael and Michelangelo. The collection is composed of approximately 300 paintings and 2,000 drawings, a rotated selection of which are available to the public for viewing in the purpose-built Christ Church Picture Gallery. Many of the works were bequeathed by a former member of the college, General John Guise (1682/3-1765), enabling the creation of the first public art gallery in Britain.[43][44][45]

Coat of arms

[edit]College arms

[edit]

The college arms are those of Cardinal Wolsey and were granted to him by the College of Arms on 4 August 1525.[46] They are blazoned: Sable, on a cross engrailed argent, between four leopards' faces azure a lion passant gules; on a chief or between two Cornish choughs proper a rose gules barbed vert and seeded or. The lion refers to Leo X who created Wolsey a Cardinal.[47][48] The arms are depicted beneath a red cardinal's galero with fifteen tassels on either side, and sometimes in front of two crossed croziers.[citation needed]

Cathedral arms

[edit]

There are also arms in use by the cathedral, which were confirmed in a visitation of 1574. They are emblazoned: "Between quarterly, 1st & 4th, France modern (azure three fleurs-de-lys or), 2nd & 3rd, England (gules in pale three lions passant guardant or), on a cross argent an open Bible proper edged and bound with seven clasps or, inscribed with the words In principio erat Verbum, et Verbum erat apud Deum and imperially crowned or."[citation needed]

Graces

[edit]The college preprandial grace reads:

| Latin | English |

|---|---|

| Nōs miserī hominēs et egēnī, prō cibīs quōs nōbis ad corporis subsidium benignē es largītus, tibi, Deus omnipotēns, Pater cælestis, grātiās reverenter agimus; simul obsecrantēs, ut iīs sobriē, modestē atque grātē ūtāmur.

Īnsuper petimus, ut cibum angelōrum, vērum panem cælestem, verbum Deī æternum, Dominum nostrum Iēsum Christum, nōbis impertiāris; utque illō mēns nostra pascātur et per carnem et sanguinem eius fovēāmur, alāmur, et corrōborēmur. Āmen. [49] |

"We unhappy and unworthy men do give thee most reverent thanks, Almighty God, our heavenly Father, for the victuals which thou hast bestowed on us for the sustenance of the body, at the same time beseeching thee that we may use them soberly, modestly and gratefully.

And above all we beseech thee to impart to us the food of angels, the true bread of heaven, the eternal Word of God, Jesus Christ our Lord, so that the mind of each of us may feed on him and that through his flesh and blood we may be sustained, nourished and strengthened. Amen." |

The first part of the grace is read by a scholar or exhibitioner before formal hall each evening, ending with the words Per Iēsum Christum Dominum nostrum ("Through Jesus Christ our Lord.") The remainder of the grace, replacing Per Iēsum Christum etc., is usually only read on special occasions.[citation needed]

There is also a long postprandial grace intended for use after meals, but this is rarely used. When High Table rises (by which time the Hall is largely empty), the senior member on High Table simply says Benedictō benedīcātur ("Let the Blessed One be blessed", or "Let a blessing be given by the Blessed One"), instead of the college postprandial grace.

Student life

[edit]

As well as rooms for accommodation, the buildings of Christ Church include the cathedral, one of the smallest in England, which also acts as the college chapel, a great hall, two libraries, two bars, and separate common rooms for dons, graduates and undergraduates. There are also gardens and a neighbouring sports ground and boat-house.[citation needed]

Accommodation is usually provided for all undergraduates, and for some graduates, although some accommodation is off-site. Accommodation is generally spacious with most rooms equipped with sinks and fridges. Many undergraduate rooms comprise 'sets' of bedrooms and living areas. Members are generally expected to dine in hall, where there are two sittings every evening, one informal and one formal (where gowns must be worn and Latin grace is read). The college offers subsidies on the costs of accommodation and dinners for UK and ROI students from families with lower household incomes.[50] The buttery next to the Hall serves drinks around dinner time. There is also a college bar (known as the Undercroft), as well as a Junior Common Room (JCR) and a Graduate Common Room (GCR), equivalent to the Middle Common Room (MCR) in other colleges.[citation needed]

There is a college lending library that supplements the university libraries (many of which are non-lending). Law students have the additional facility of the Burn Law Library, named for Edward Burn.[51] Most undergraduate tutorials are carried out in the college, though for some specialist subjects undergraduates may be sent to tutors in other colleges.[citation needed]

Croquet is played in the Masters' Garden in the summer. The sports ground is mainly used for netball, cricket, tennis, rugby and football and includes Christ Church cricket ground. In recent years the Christ Church Netball Club, which competes on the inter-college level in both mixed and women's matches, has become known as a popular and inclusive sport. Rowing and punting is carried out by the boat-house across Christ Church Meadow – the Christ Church Boat Club is traditionally strong at rowing, having been Head of the River more than all other colleges except Oriel College. The college also owns its own punts which may be borrowed by students or dons.[citation needed]

The college beagle pack (Christ Church and Farley Hill Beagles), which was formerly one of several undergraduate packs in Oxford, is no longer formally connected with the college or the university but continues to be staffed and followed by some Oxford undergraduates.[citation needed]

Christ Church references

[edit]"Midnight has come and the great Christ Church bell

And many a lesser bell sound through the room;

And it is All Souls' Night..."

— W B Yeats, All Souls' Night, Oxford (1920)

"The wind had dropped. There was even a glimpse of the moon riding behind the clouds. And now, a solemn and plangent token of Oxford's perpetuity, the first stroke of Great Tom sounded."

— Max Beerbohm, Chapter 21, Zuleika Dobson (1922)

"I must say my thoughts wandered, but I kept turning the pages and watching the light fade, which in Peckwater, my dear, is quite an experience – as darkness falls the stone seems positively to decay under one's eyes. I was reminded of some of those leprous façades in the vieux port at Marseille, until suddenly I was disturbed by such a bawling and caterwauling as you never heard, and there, down in the little piazza, I saw a mob of about twenty terrible young men, and do you know what they were chanting We want Blanche. We want Blanche! in a kind of litany."

— Evelyn Waugh, Brideshead Revisited (1945)

"Those twins / Of learning that he [Wolsey] raised in you,

Ipswich and Oxford! one of which fell with him,

Unwilling to outlive the good that did it;

The other, though unfinish'd, yet so famous,

So excellent in art, and still so rising,

That Christendom shall ever speak his virtue."

— William Shakespeare, Henry VIII (1613)

"By way of light entertainment, I should tell the Committee that it is well known that a match between an archer and a golfer can be fairly close. I spent many a happy evening in the centre of Peckwater Quadrangle at Christ Church, with a bow and arrow, trying to put an arrow over the Kilcannon building into the Mercury Pond in Tom Quad. On occasion, the golfer would win and, on occasion, I would win. Unfortunately, that had to stop when I put an arrow through the bowler hat of the head porter. Luckily, he was unhurt and bore me no ill will. From that time on he always sent me a Christmas card which was signed 'To Robin Hood from the Ancient Briton'"

— Lord Crawshaw, House of Lords, Hansard (Tuesday 8 July 1997)

"There is one oddity; Rudge. Determined to try for Oxford, Christ Church of all places! Might get into Loughborough, in a bad year."

— Alan Bennett, The History Boys (2004)

" And once, in winter, on the causeway chill

Where home through flooded fields foot-travellers go,

Have I not pass'd thee on the wooden bridge,

Wrapt in thy cloak and battling with the snow,

And thou has climb'd the hill,

And gain'd the white brow of the Cumner range;

Turn'd once to watch, while thick the snowflakes fall,

The line of festal light in Christ-Church hall—

Then sought thy straw in some sequester'd grange. "

— Matthew Arnold, The Scholar Gypsy (1853)

Also included in: Vaughan Williams|An Oxford Elegy (1947–9) and Hilary Mantel's Wolf Hall trilogy (referred to by its previous name, Cardinal College).

People associated with the college

[edit]Deans

[edit]Cardinal College

- 1525: John Hygdon

King Henry VIII's College

- 1532: John Hygdon

- 1533: John Oliver

Christ Church

Alumni

[edit]-

Lewis Carroll, author

-

Edward VII, former King of the United Kingdom

-

John Locke, philosopher and physician

-

John Wesley, cleric and founder of Methodism

Notable former students of the college have included politicians, scientists, philosophers, entertainers and academics. Thirteen British prime ministers have studied at the college including, Anthony Eden (Prime Minister 1955–1957), William Ewart Gladstone (1828–1831), Sir Robert Peel (1841–1846) and Archibald Primrose (1894–1895). Other former students include Charles Abbot (Speaker of the House of Commons 1802–1817), Frederick Curzon (Conservative Party statesman 1951–), Nicholas Lyell (Attorney General 1992–1997), Nigel Lawson (Chancellor of the Exchequer 1983–1989), Quintin Hogg (Lord Chancellor 1979–1987) and William Murray (Lord Chief Justice 1756–1788 and Chancellor of the Exchequer 1757). From outside the UK, politicians from Canada (Ted Jolliffe), Pakistan (Zulfikar Ali Bhutto), Sri Lanka (S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike) and the United States (Charles Cotesworth Pinckney) have attended the college.

Prominent philosophers including John Locke, John Rawls, A. J. Ayer, Gilbert Ryle, Michael Dummett, John Searle and Daniel Dennett studied at Christ Church.

There are numerous former students in the fields of academia and theology, including George Kitchin (the first Chancellor of the University of Durham 1908–1912 and Dean of Durham Cathedral 1894–1912), John Charles Ryle (first Bishop of Liverpool 1880–1900), John Wesley (leader of the Methodist movement), Rowan Williams (Archbishop of Canterbury 2002–2012), Richard William Jelf (Principal of King's College London 1843–1868), Ronald Montagu Burrows (Principal of King's College London 1913–1920) and William Stubbs (Bishop of Oxford 1889–1901 and historian).

Two Olympic rowing gold medallists studied at the college: Jonny Searle and Spanish Civil War volunteer Lewis Clive.[52][53]

In the sciences, polymath and natural philosopher Robert Hooke, developmental biologist John B. Gurdon (co-winner of the 2012 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine), physician Sir Archibald Edward Garrod, the Father of Modern Medicine Sir William Osler, biochemist Kenneth Callow, radio astronomer Sir Martin Ryle, psychologist Edward de Bono and epidemiologist Sir Richard Doll are all associated with the college. Albert Einstein was a learned research fellow.

In other fields, Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss, twins associated with the founding of Facebook, King Edward VII (1841–1910), King of the United Kingdom and Emperor of India, King William II of the Netherlands, Prince Paul of Yugoslavia, entrepreneur and founder of Pennsylvania William Penn, broadcaster David Dimbleby, MP Louise Mensch, BBC composer Howard Goodall, actor Riz Ahmed, the writer Lewis Carroll, poet W. H. Auden, and the former officer of arms Hubert Chesshyre are other notable students to have previously studied at Christ Church.

Gallery

[edit]-

Peckwater Quad

-

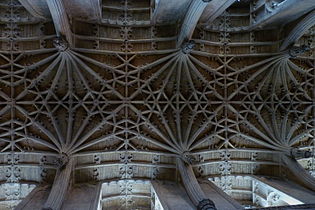

Cathedral vault and rose window

-

Cathedral chancel vault

-

Cathedral altar

-

St Cecilia's window, in the cathedral

-

Hall

-

War Memorial gardens

-

The Grand Staircase

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Christ Church, Oxford (19 March 2015). "Statutes of Christ Church Oxford" (PDF). chch.ox.ac.uk. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 April 2022. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- ^ "Student statistics". University of Oxford. 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ^ "Financial Statements of the Oxford Colleges 2021–22". ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 5 April 2023.

- ^ a b "Christ Church | University of Oxford". www.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- ^ "Financial Statements of the Oxford Colleges 2021–22 | University of Oxford". www.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ "Harry Potter fans boost Oxford Christ Church Cathedral". BBC News. 25 March 2012. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "Award winners | University of Oxford". www.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- ^ Cowie, D. J. (1934). "How Christchurch Got Its Name – A Controverted Subject". Victoria University of Wellington. Archived from the original on 10 June 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- ^ Willoughby, James (October 2015). "Thomas Wolsey and the books of Cardinal College, Oxford". Bodleian Library Record. 28 (2): 114–134.

- ^ "The Governing Body – Westminster School". Westminster School. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ "Westminster School Intranet". Intranet.westminster.org.uk. Archived from the original on 13 July 2012. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- ^ Horan, David (1999). Oxford: A Cultural and Literary Companion. p. 19. ISBN 9781902669052.

- ^ "A Brief History of Christ Church" (PDF). Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ Varley, Frederick John (1932). The Siege of Oxford: An Account of Oxford during the Civil War, 1642–1646. Oxford University Press. p. 128.

- ^ "A Brief History of Christ Church" (PDF). Christ Church, Oxford. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ "Annual Report and Financial Statements" (PDF). Christ Church. 31 July 2017. p. 5. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ "Christ Church Oxford : Annual Report and Financial Statements : Year ended 31 July 2018" (PDF). ox.ac.uk. p. 21. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- ^ "Christ Church website". Archived from the original on 30 September 2015.

- ^ "15/00760/FUL | Change of use and extension of existing thatched barn ... |Christ Church College". public.oxford.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ "A Brief History". Friends of Aston's Eyot. 24 December 2014. Archived from the original on 1 September 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ Brockliss, Laurence (28 July 2016). Magdalen College School. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 45. ISBN 9781784421533.

- ^ "The Meadow | Christ Church, Oxford University". www.chch.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "Sadler inscription in Deadman's Walk". www.oxfordhistory.org.uk. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ Historic England. "Christ Church (1000441)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ Historic England. "CHRISTCHURCH, MERCURY FOUNTAIN, THE GREAT QUADRANGLE, Oxford (1046740)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ Historic England. "THE CHAPTER HOUSE AND DORTER RANGE TO SOUTH OF CATHEDRAL, Oxford (1046739)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "The Chapter House | Christ Church, Oxford University". www.chch.ox.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 10 September 2019. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Pococke Garden". Christ Church. Retrieved 23 August 2022.

- ^ "The World Behind Alice in Wonderland in Oxford". Untapped Cities. 4 December 2012. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "Alice in Wonderland Oxford | Experience Oxfordshire". Experience Oxfordshire. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "MNHA – Musée National d'Histoire et d'Art – Luxembourg – The patron, William II". www.mnha.lu. Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "Willem II: kunstkoning -". CODART. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "Edward Burne-Jones". Southgate Green Association. Archived from the original on 24 March 2020. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

His work included both stained-glass windows for Christ Church in Oxford and the stained glass windows for Christ Church on Southgate Green.

- ^ PreRaphaelite Painting and Design Archived 14 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine University of Texas

- ^ News· (19 May 2010). "Competitors shell-shocked by tortoise scandal". The Oxford Student. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ "Dr Lucy Taylor blog post gallery | Christ Church, Oxford University". www.chch.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ Christ Church [@ChCh_Oxford] (8 April 2021). "Tom and Peck, the Christ Church ducks are back! Maybe we'll soon see some ducklings waddling around Tom Quad?? 🦆🦆 Thanks to @LucyATaylor for the up-close-and-personal photo. #ChristChurchTogether #TomTower9o5 #ChChimes #ducks https://t.co/BpPyd6UwQt" (Tweet). Archived from the original on 12 June 2022. Retrieved 13 December 2022 – via Twitter.

- ^ @ChCh_Oxford (27 September 2022). "Bye bye fish!" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ "The Meadow | Christ Church, Oxford University". www.chch.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ Worden, Blair (2015). Hugh Trevor-Roper: The Historian. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 9780857729880.

As an undergraduate at Christ Church he attended the High Church services in the cathedral that is part of the college,...

- ^ "Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford". Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ "Treasures of Christ Church". 7 March 2011. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ Christ Church Picture Gallery Archived 15 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Christ Church, Oxford; 22 January 2013. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- ^ "Christ Church Matters, Issue 35" (PDF). pp. 12–15. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

- ^ "Old Masters in an Oxford museum". Financial Times. 4 September 2010. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2015.

- ^ Curthoys, Judith (2012). The Cardinal's College: Christ Church, Chapter and Verse. Profile Press. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-1-84668-617-7.

- ^ "Oxford University and its Colleges". The Heraldry Society. 4 March 2018. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ^ Marlin, J T (2018). Oxford College Arms. Boissevain Books LLC. ISBN 9781087853130.

- ^ Adams, Reginald (1992). The college graces of Oxford and Cambridge. Perpetua Press. pp. 62–64. ISBN 978-1-870882-06-4.

- ^ "Funding Your Studies page, Christ Church". Archived from the original on 10 September 2017.

- ^ "Professor Edward Burn obituary". Retrieved 9 March 2022.

- ^ "Lewis Clive athletic history". Sports Reference. 18 April 2020. Archived from the original on 18 April 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ Farman, Chris; Rose, Valery; Woolley, Liz (2015). No Other Way: Oxfordshire and the Spanish Civil War 1936–39. UK: Oxford International Brigade Memorial Committee. p. 63. ISBN 9781910448052.

External links

[edit]- Christ Church, Oxford

- Colleges of the University of Oxford

- Educational institutions established in the 1540s

- Grade I listed buildings in Oxford

- Grade I listed educational buildings

- Augustinian monasteries in England

- Buildings and structures of the University of Oxford

- 1546 establishments in England

- Grade I listed parks and gardens in Oxfordshire

- Henry VIII