Abstract

Background

Due to a nationwide shortage of anesthesia assistants, operating room nurses are often recruited to assist with the induction of obstetric general anesthesia (GA). We developed and administered a training program and hypothesized there would be significant improvements in knowledge and skills in anesthesia assistance during obstetric GA by operating room nurses following training with adequate retention at six months.

Methods

Following informed consent, all operating room nurses at our institution were invited to participate in the study. Baseline knowledge of participants was assessed using a 14-item multiple choice questionnaire (MCQ), and skills were assessed using a 12-item checklist scored by direct observation during simulated induction of GA. Next, a 20-min didactic lecture followed by a ten-minute hands-on skills station were delivered. Knowledge and skills were immediately reassessed after training, and again at six weeks and six months. The primary outcomes of this study were adequate knowledge and skills retention at six months, defined as achieving ≥ 80% in MCQ and ≥ 80% in skills checklist scores and analyzed using longitudinal mixed-effects linear regression.

Results

A total of 34 nurses completed the study at six months. The mean MCQ score at baseline was 8.9 (95% confidence interval [CI], 8.5 to 9.4) out of 14. The mean skills checklist score was 5.5 (95% CI, 4.9 to 6.1) out of 12. The mean comfort scores for assisting elective and emergency Cesarean deliveries were 3.6 (95% CI, 3.2 to 3.9) and 3.1 (95% CI, 2.7 to 3.5) out of 5, respectively. There was a significant difference in the mean MCQ and skills checklist scores across the different study periods (overall P value < 0.001). Post hoc pairwise tests suggested that, compared with baseline, there were significantly higher mean MCQ scores at all time points after the training program at six weeks (11.9; 95% CI, 11.4 to 12.4; P < 0.001) and at six months (12.0; 95% CI, 11.5 to 12.4; P < 0.001).

Discussion

The knowledge and skills of operating room nurses in providing anesthesia assistance during obstetric GA at our institution were low at baseline. Following a single 30-min in-house, anesthesiologist-led, structured training program, scores in both dimensions significantly improved. Although knowledge improvements were adequately retained for up to six months, skills improvements decayed rapidly, suggesting that sessions should be repeated at six-week intervals, at least initially.

Résumé

Contexte

En raison d’une pénurie nationale d’assistants en anesthésie, le personnel infirmier de la salle d’opération est souvent sollicité pour aider à l’induction de l’anesthésie générale (AG) obstétricale. Nous avons élaboré et administré un programme de formation et émis l’hypothèse qu’il y aurait des améliorations significatives dans les connaissances et les compétences en matière d’assistance en anesthésie pendant l’anesthésie générale obstétricale par les infirmières de salle d’opération après avoir suivi une formation, avec une rétention adéquate à six mois.

Méthode

Après avoir obtenu le consentement éclairé, tout le personnel infirmier de salle d’opération de notre établissement a été invité à participer à l’étude. Les connaissances de base des participants ont été évaluées à l’aide d’un questionnaire à choix multiples (QCM) à 14 éléments, et les compétences ont été évaluées à l’aide d’une liste de contrôle de 12 éléments notée par observation directe lors d’une simulation d’induction d’anesthésie générale. Par la suite, un cours didactique de 20 minutes suivi d’une station de compétences pratiques de dix minutes a été donné. Les connaissances et les compétences ont été réévaluées immédiatement après la formation, puis de nouveau à six semaines et six mois. Les critères d’évaluation principaux de cette étude étaient la rétention adéquate des connaissances et des compétences à six mois, définie comme l’atteinte de ≥ 80 % dans les scores du QCM et ≥ 80 % dans les scores de la liste de contrôle des compétences et analysée à l’aide d’une régression linéaire longitudinale à effets mixtes.

Résultats

Au total, 34 infirmières ont terminé l’étude à six mois. Au début de l’étude, le score moyen au QCM était de 8,9 (intervalle de confiance [IC] à 95 %, 8,5 à 9,4) sur 14. Le score moyen sur la liste de contrôle des compétences était de 5,5 (IC 95 %, 4,9 à 6,1) sur 12. Les scores moyens d’aisance dans l’assistance pour un accouchement par césarienne programmé et d’urgence étaient de 3,6 (IC 95 %, 3,2 à 3,9) et 3,1 (IC 95 %, 2,7 à 3,5) sur 5, respectivement. Une différence significative a été observée dans les scores moyens au QCM et sur la liste de contrôle des compétences entre les différentes périodes d’étude (valeur globale P < 0,001). Les tests appariés post-hoc ont suggéré que, par rapport aux connaissances évaluées au début de l’étude, les scores moyens au QCM étaient significativement plus élevés à tous les moments après le programme de formation, à six semaines (11,9; IC 95 %, 11,4 à 12,4; P < 0,001) et à six mois (12,0; IC 95 %, 11,5 à 12,4; P < 0,001).

Discussion

Les connaissances et les compétences du personnel infirmier de salle d’opération dans la prestation d’une assistance en anesthésie pendant l’AG obstétricale dans notre établissement étaient faibles au commencement de notre étude. Après un seul programme de formation structuré de 30 minutes à l’interne, dirigé par un anesthésiologiste, les scores dans les deux dimensions se sont considérablement améliorés. Bien que les améliorations des connaissances aient été retenues de manière adéquate jusqu’à six mois, les améliorations des compétences se sont rapidement détériorées, ce qui suggère que les séances devraient être répétées à des intervalles de six semaines, au moins au début.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Administering obstetric general anesthesia (GA) for emergency Cesarean delivery is challenging. The anatomical and physiologic changes in pregnancy render the patient at increased risk of airway complications during induction of GA.1 From the moment the pregnant patient enters the operating room, multiple steps must rapidly and correctly occur to facilitate a prompt operative delivery.2 During this time-pressed sequence of events, numerous human factors are at play that could influence safe and successful outcomes for the patient and neonate.3,4,5

In Canada, anesthesia assistants (AAs) are credentialed healthcare professionals who have pursued a defined period of didactic and clinical training. Anesthesia assistants are part of an anesthesia care team and execute medical orders and directives as prescribed by anesthesiologists.6 At our institution, a tertiary obstetric unit, an AA is usually the first-assist for the anesthesiologist during obstetric GA. A nationwide shortage of AAs has meant they are not always reliably present. In the absence of an AA or other anesthesia team members, operating room nurses are requested to act as first-assist; however, they are often unfamiliar with anesthesia assistance and are uncomfortable in this role because of an overall low institutional rate of obstetric GA and a high rate of nursing turnover.

To enhance the operating room nurses’ confidence and competence in acting as first-assist, we designed a prospective observational study to investigate the effects of an anesthesiologist-led, in-house, structured training program on operating room nurses’ knowledge and skills in providing anesthesia assistance during emergency Cesarean delivery under GA. We hypothesized that, following a structured training program, knowledge and skills would significantly improve from baseline with adequate retention at six months.

Methods

Setting and study population

Institutional ethics committee approval was sought and review was exempted because the project fulfilled criteria as a quality improvement study. This article adheres to the STROBE guidelines.

From 1 October 2018 to 31 May 2019, all nurses who worked in the operating rooms at BC Women’s Hospital were eligible and invited to participate following written informed consent. Recruitment of participants was promoted with the help of nurse educators at morning team huddles and via study information posters. As an incentive, all participants received a coffee gift card of CAD 10 for completing the structured training program.

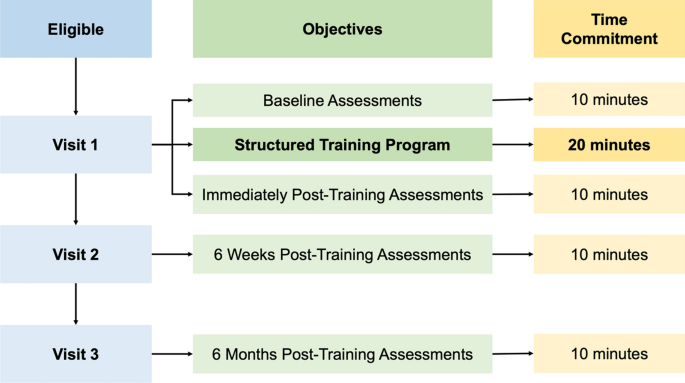

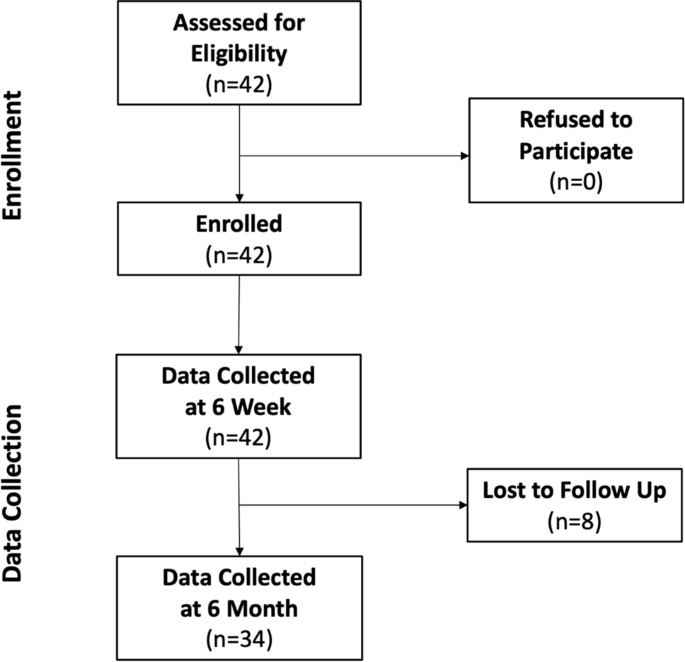

At the time of the study, BC Women’s Hospital was a tertiary obstetric unit that only performed obstetric and ambulatory gynecological procedures with separate obstetrics and gynecology operating room nursing teams. The main clinical exposure to GA for nurses working in the obstetric operating rooms included GA for Cesarean deliveries, antepartum patients requiring cerclage placements, or postpartum patients requiring emergency surgeries for dilation and curettage procedures or management of postpartum hemorrhage. Study and participant flows are detailed in Figs 1 and 2, respectively.

Development of knowledge and skills objectives

A series of learning objectives around the provision of anesthesia assistance during GA were developed following a literature search and review of the Canadian Anesthesiologists’ Society Position Paper on Anesthesia Assistants.6,7,8

The objectives were then reviewed by three fellowship-trained obstetric anesthesiologists within the department and finalized into 14 knowledge and six skills objectives (Table 1). The objectives are primarily focused on intraoperative monitors (e.g., correct selection, placement and troubleshooting) and airway management (e.g., recognition of airway equipment, positioning of the patient, how to correctly preoxygenate, and how to perform cricoid pressure). Based on the objectives, a 30-min training program was developed, composed of a 20-min didactic lecture and a ten-minute skills station delivered to the participants in groups of two to three each time. No preparation work was necessary before the training. To minimize interindividual variation in teaching, the didactic and skills station were all taught by a single anesthesiologist.

Outcomes assessment

The primary outcomes of this study were adequate knowledge and skills retention by operating room nurses at six months. Secondary outcomes included knowledge and skills acquisition at baseline immediately after the training program, knowledge and skills retention at six weeks, operating room nurses’ level of comfort scores in assisting in obstetric GA, and the proportion of anesthesiologists feeling adequate assistance had been provided during obstetric GA.

Participants’ knowledge was assessed by a ten-item multiple-choice questionnaire (MCQ) with a maximum score of 14 that was devised from the knowledge objectives (see Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM] eAppendix 1). To assess knowledge acquisition of the course content, participants were asked to complete the MCQ at baseline immediately before and then immediately after the training session. To assess knowledge retention, the MCQ was readministered at six weeks and six months after the training session. The same MCQ content was used at each administration with the order of questions and answers randomized using a random sequence generator.

Adequate knowledge acquisition and retention were defined as a group mean MCQ score of ≥ 80% post-training (i.e., mean MCQ score ≥ 11.2 out of 14). As part of the MCQ, seven questions surveyed demographic information.

Participants’ skills were assessed by a 12-item checklist with a maximum score out of 12 based on the skill objectives (see ESM eAppendix 2). Each skill competency was shown by the training anesthesiologist during the skills component of the training session with opportunities for each participant to perform each task. Each nurse was assessed separately, in the operating room immediately after the knowledge MCQ test. Each correct performance of a skill was awarded 1 point and each incorrect action or non-attempt of a skill was given 0 points. Adequate skills acquisition and retention were defined as a group mean skills checklist score of ≥ 80% post-training (i.e., mean skills score ≥ 9.6 out of 12). Skills were assessed at the same time points (i.e., baseline, immediately after the program, six weeks, and six months). Answers to MCQs and skills assessments were provided to all participants at the end of the study period.

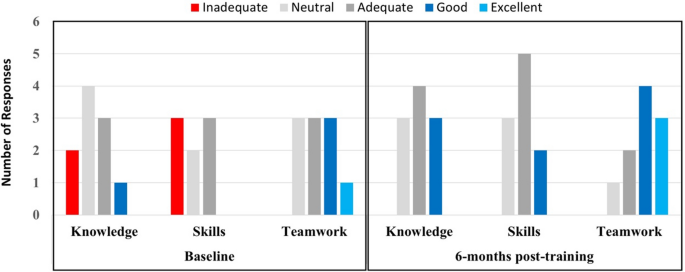

All participants were asked to report their comfort level at assisting the anesthesiologist during scheduled and emergency obstetric GA using a five-point Likert scale (5 = strongly agree; 4 = agree; 3 = neutral; 2 = disagree; 1 = strongly disagree) at baseline, 6 weeks, and 6 months post-training. Ten obstetric anesthesiologists were asked to rate their perception of the nursing staff’s knowledge and skills, and good teamwork with the nursing team during obstetric GA using a five-point Likert scale (1 = inadequate; 2 = neutral; 3 = adequate; 4 = good; 5 = excellent). The same anesthesiologists were surveyed at all time points.

Sample size

A list containing the full membership of all operating room nurses was obtained from the nursing lead; a total of 42 operating room nurses were eligible at BC Women’s Hospital. To maximize the impact of our training session, we recruited all 42 nurses.

Statistical analysis

Knowledge and skills acquisition and retention over time were estimated using longitudinal mixed-effects linear regression to account for repeated studies on the same person. Similarly, the subjective comfort scores of nurses in assisting with GA were estimated using longitudinal mixed-effects linear regression. Time was entered as the categorical variable, indicating the different study steps at baseline, immediately after, at six weeks, and six months after the training program. Results were adjusted for participants’ experience, years practising as a nurse, years practising in the operating room, average number of clinical shifts per week, completion of a recent airway training course, and number of GA cases nurses had previously assisted with.

Results

A total of 42 operating room nurses participated in the training program and had follow-up data at six weeks. At six months, data from 34 of these nurses were available. Participant flow is detailed in Fig. 2. Baseline participant characteristics are shown in Table 2.

Baseline knowledge, skills and comfort

Both knowledge and skills were low at baseline. Out of the highest possible knowledge score of 14, the mean MCQ score at baseline was 8.9 (95% confidence interval [CI], 8.5 to 9.4). Out of the highest possible skills score of 12, the mean checklist score was 5.5 (95% CI, 4.9 to 6.1). Out of the highest possible score of 5, the mean comfort scores for assisting elective and emergency Cesarean deliveries were 3.6 (95% CI, 3.2 to 3.9) and 3.1 (95% CI, 2.72 to 3.5), respectively. Survey results of anesthesiologists’ baseline perception of nursing staff assisting with obstetric GA are presented in Fig. 3.

Baseline and 6-month post-structured training program survey of anesthesiologists’ perception of nursing staff’s knowledge and skills during obstetric general anesthesia and perception of good teamwork with the nursing team during obstetric general anesthesia. The same anesthesiologists were surveyed for both periods

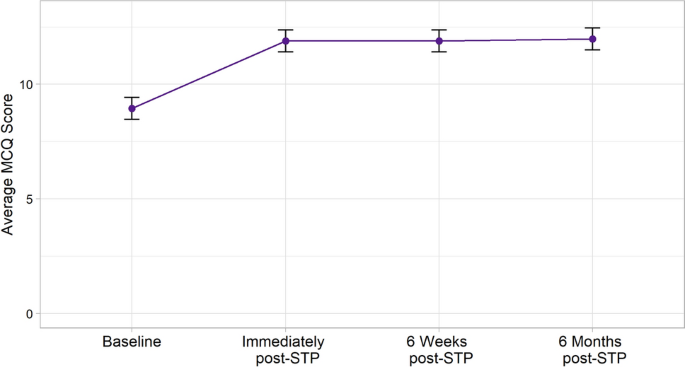

Knowledge outcomes

There was a significant difference in the mean MCQ scores across the different study periods (overall P value < 0.001). Post hoc pairwise tests suggested that compared with baseline, there were significantly higher mean MCQ scores at all time points after the training program: immediately after training (11.9; 95% CI, 11.4 to 12.4 vs 8.9; 95% CI, 8.5 to 9.4; P < 0.001), at six weeks (11.9; 95% CI, 11.4 to 12.4 vs 8.9; 95% CI, 8.5 to 9.4; P < 0.001) and at six months (12.0; 95% CI, 11.5 to 12.4 vs 8.9; 95% CI, 8.5 to 9.4; P < 0.001).

For knowledge decay analysis, there was no difference in mean MCQ scores between the time points after training (e.g., immediately after, at six weeks, and six months after the training program) (see Fig. 4).

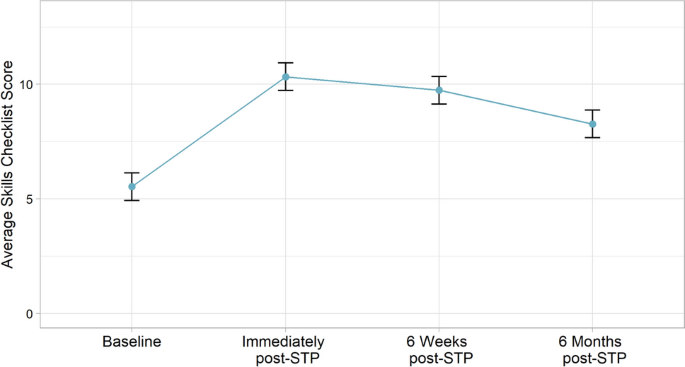

Skills outcomes

There was a significant difference in the mean skills checklist score across the different study periods (overall P value < 0.001). Post hoc pairwise tests suggested that mean skills checklist scores were significantly higher immediately after the training program than at baseline (10.3; 95% CI, 9.7 to 10.9 vs 5.5; 95% CI, 4.9 to 6.1; P < 0.001), at six weeks (9.7; 95% CI, 9.1 to 10.3 vs 5.5; 95% CI, 4.9 to 6.1; P <0.001), and at six months after the training program (8.3; 95% CI, 7.7 to 8.9 vs 5.5; 95% CI, 4.9 to 6.1; P < 0.001).

For skills decay analysis, compared with immediately after the training program, there were significantly lower mean skills checklist scores at six weeks (9.7; 95% CI, 9.1 to 10.3 vs 10.3; 95% CI, 9.7 to 10.9; P = 0.048), and six months (8.3; 95% CI, 7.7 to 8.9 vs 10.3; 95% CI, 9.7 to 10.9; P < 0.001). The mean checklist scores at six weeks and six months were also significantly different (9.7; 95% CI, 9.1 to 10.3 vs 8.3; 95% CI, 7.7 to 8.9; P < 0.001) (see Fig. 5).

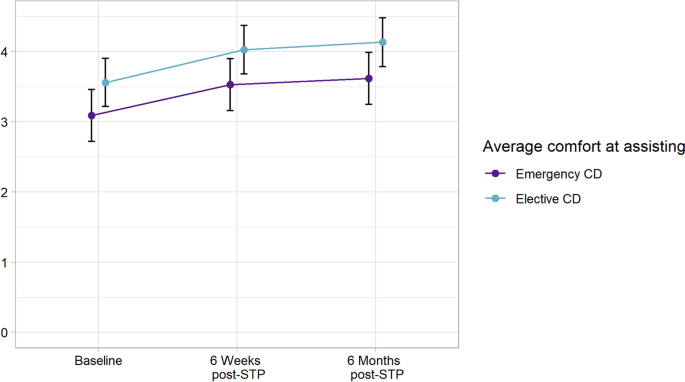

Comfort outcomes

There was a significant difference in mean comfort values in assisting elective or emergency Cesarean deliveries cases across the different study steps (overall P value < 0.001). For comfort in assisting with elective obstetric GA, post hoc pairwise tests suggest that, compared with baseline scores, there were significantly higher mean comfort scores at six weeks (4.0; 95% CI, 3.7 to 4.4 vs 3.6; 95% CI, 3.2 to 3.9; P < 0.0029) and six months after the training program (4.13; 95% CI, 3.79 to 4.48 vs 3.56; 95% CI, 3.22 to 3.90; P < 0.001), with no difference between six weeks and six months (P = 0.48).

For comfort assisting in emergency obstetric GA, post hoc pairwise tests suggest that, compared with baseline scores, there were significantly higher mean comfort scores at 6 weeks (3.5; 95% CI, 3.2 to 3.9; vs 3.1; 95% CI, 2.7 to 3.5; P < 0.001) and at 6 months after the training program (3.6; 95% CI, 3.2 to 4.0 vs 3.09; 95% CI, 2.7 to 3.5; P <0.001), with no difference between 6 weeks and 6 months (P = 0.44) (Fig. 6).

At 6 months after training, no anesthesiologists showed inadequate knowledge, skills, or teamwork (Fig. 3).

There were no changes to knowledge, skills, and comfort levels after adjusting for baseline and covariates (see ESM eTable 1 and eTable 2).

Discussion

In this prospective cohort study, we found that the knowledge and skills of operating room nurses in providing anesthesia assistance during obstetric GA at a tertiary obstetric unit were all low at baseline. Following a single 30-min, in-house, anesthesiologist-led, structured training program, scores in both dimensions significantly improved. Importantly, the improvements in knowledge were adequately retained for up to six months, but the improvements in skills decayed rapidly.

Inadequate skilled assistance has been identified as a contribution to significant patient safety events in anesthesia while the presence of trained assistants during anesthesia has been shown to reduce errors and adverse outcomes.3,4,5,9 Our results are particularly relevant given the current national shortage of AAs and the frequent turnover of nursing staff.10 Even centres that are well-staffed with AAs may not have an AA immediately available at the exact time when help is required during an emergency Cesarean delivery. Some institutions have recognized this need and developed an “above the waist” nursing role to assist the anesthesiologist to minimize task saturation and prepare for induction of GA.2 Adopting a local training program could prepare all nursing staff to assist, with the added benefit of improving interprofessional teamwork and collaboration.

Several factors influence the ability to retain new knowledge and skills, which may explain the diverging pattern of decay between knowledge and skills observed in our study. Substantial skill loss occurs when new skills are not used or practiced routinely.11,12 The more rapid decay in skills may be in part due to overall low exposure to a shrinking number of obstetric GA cases, creating little opportunity to reinforce new skills. The difficulty retaining skills with training interventions has been observed in several settings associated with low exposure events, including neonatal resuscitation and advanced cardiac life support.13,14,15

Prior experience also influences performance after training interventions and the ability to retain skills.16 Our participants had low baseline knowledge as shown on baseline MCQ scores and many had received no formal training in the technique of providing anesthesia assistance prior to our intervention. This may explain the difficulty some of our participants had in retaining skills. It may also explain why our results are in contrast to other studies in the area, including one study that showed anesthesia residents maintained competency in performing GA for Cesarean delivery at up to eight months17 and another study showing retention of both knowledge and skills among nurses and physicians in providing emergency obstetric care at 12 months.11 These studies involved participants already familiar with the techniques taught, which facilitated easier retention.

Importantly, our results showed improved comfort of participants in assisting with anesthesia. The confidence of caregivers in executing a task is a significant factor influencing performance and the patient experience.18 Improving staff comfort may, in turn, strengthen teamwork and reduce the risk of medical error, thus improving overall patient safety.19 Improvement of comfort levels also has important implications for staff wellbeing. Managing emergency situations that one has not previously been exposed to is psychologically distressing for staff,20 which may also influence performance in other routine tasks.21 We showed that a simple in-house anesthesiologist-led program helped some operating room nurses cope with the potential stress stemming from assisting with GA.

The ideal time to repeat a program such as ours depends on an array of factors, including the nature of the task being taught, the context in which it is being used, and the experience of participants.12 It is inevitable that both knowledge and skills acquired will decay significantly over time without periodic testing and refresher courses.12,22,23 Our results suggest that repeating sessions at six-week intervals is appropriate, at least initially. Such a schedule would require significant institutional support but could form part of regular obstetric interprofessional team training, which is recommended by several authors.16,24,25 Nevertheless, over time, the interval could lengthen as recall is augmented with repetition. Our program could be modified to include simulation training in non-technical skills, given the evidence to support this.24,26,27,28 In addition, the benefits of our intervention could be enhanced by providing structured feedback reports to participants.29

There are several limitations to our study. First, our program was undertaken at a single institution with small sample size, although this was limited by the number of nurses available in our institution. Second, we did not prospectively collect real-life clinical data from GA performed before or after the intervention and participants were allowed to look up information on their own between assessments to further their learning. Therefore, any improvement in scores may not be directly attributable to the structured training program. Third, our assessment tools were not validated and parts of our program, such as the correct sequence we recommend to apply monitors, are specific to our institutional workflow. It is possible we were simply measuring recall rather than knowledge synthesis and that retention of knowledge was attributable in part to the testing effect, where retrieval of information from memory by administering tests increases the long-term retention of that information.30,31 Finally, we adjusted for several baseline variables in our analysis but there may be residual confounders, which may impact performance. For example, it is plausible that the age of the participants may influence learning and thus knowledge and skills retention; however, we did not ask participants to report age in the study as we felt some participants may be sensitive to sharing this information.

Having dedicated skilled assistance during obstetric GA is a challenge faced by many Canadian obstetric units. We hope this study will highlight the important role served by operating room nurses, who may provide anesthesia assistance in some hospitals and the training required for them to mount sufficient knowledge, skills and comfort to aid the anesthesiologist during induction of GA for emergency Cesarean delivery. Hospital leads should recognize and address the shortage of AAs and facilitate efforts to develop clinically competent personnel to assist anesthesiologists. We believe implementing and replicating this quality improvement effort may be a simple, cost-effective, and worthwhile endeavour to boost interprofessional teamwork and patient safety.

References

Kinsella SM, Winton AL, Mushambi MC, et al. Failed tracheal intubation during obstetric general anaesthesia: a literature review. Int J Obstet Anesth 2015; 24: 356-74.

Lipman SS, Carvalho B, Cohen SE, Druzin ML, Daniels K. Response times for emergency cesarean delivery: use of simulation drills to assess and improve obstetric team performance. J Perinatol 2013; 33: 259-63.

Kluger MT, Bukofzer M, Bullock M. Anaesthetic assistants: their role in the development and resolution of anaesthetic incidents. Anaesth Intensive Care 1999; 27: 269-74.

Weller JM, Merry AF, Robinson BJ, Warman GR, Janssen A. The impact of trained assistance on error rates in anaesthesia: a simulation-based randomised controlled trial. Anaesthesia 2009; 64: 26-30.

McFarlane HJ, van der Horst N, Kerr L, McPhillips G, Burton H. The Scottish Audit of Surgical Mortality: a review of areas of concern related to anaesthesia over 10 years. Anaesthesia 2009; 64: 1324-31.

The Canadian Anesthesiologists’ Society. Position Paper on Anesthesia Assistants: An Official Position Paper of the Canadian Anesthesiologists’ Society. Available from URL: https://www.cas.ca/CASAssets/Documents/Section/97_Appendix-5.pdf (accessed March 2022).

Mushambi MC, Kinsella SM, Popat M, et al. Obstetric Anaesthetists' Association and Difficult Airway Society guidelines for the management of difficult and failed tracheal intubation in obstetrics. Anaesthesia 2015; 70: 1286-306.

Mushambi MC, Jaladi S. Airway management and training in obstetric anaesthesia. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2016; 29: 261-7.

Fioratou E, Flin R, Glavin R. No simple fix for fixation errors: cognitive processes and their clinical applications. Anaesthesia 2010; 65: 61-9.

Havaei F, Ma A, Leiter M, Gear A. Describing the mental health state of nurses in British Columbia: a province-wide survey study. Healthc Policy 2021; 16: 31-45.

Ameh CA, White S, Dickinson F, Mdegela M, Madaj B, van den Broek N. Retention of knowledge and skills after emergency obstetric care training: a multi-country longitudinal study. PLoS One 2018; https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0203606.

Arthur W Jr, Bennett W Jr, Stanush PL, McNelly TL. Factors that influence skill decay and retention: a quantitative review and analysis. Hum Perform 1998; 11: 57-101.

Patel J, Posencheg M, Ades A. Proficiency and retention of neonatal resuscitation skills by pediatric residents. Pediatrics 2012; 130: 515-21.

Yang CW, Yen ZS, McGowan JE, et al. A systematic review of retention of adult advanced life support knowledge and skills in healthcare providers. Resuscitation 2012; 83: 1055-60.

Au K, Lam D, Garg N, et al. Improving skills retention after advanced structured resuscitation training: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Resuscitation 2019; 138: 284-96.

Oates JL. Skills fade: a review of the evidence that clinical and professional skills fade during time out of practice, and of how skills fade may be measured or remediated. General Medical Council; 2014. Available from URL: https://www.gmc-uk.org/about/what-we-do-and-why/data-and-research/research-and-insight-archive/skills-fade-literature-review (accessed March 2022).

Ortner CM, Richebé P, Bollag LA, Ross BK, Landau R. Repeated simulation-based training for performing general anesthesia for emergency cesarean delivery: long-term retention and recurring mistakes. Int J Obstet Anesth 2014; 23: 341-7.

Owens KM, Keller S. Exploring workforce confidence and patient experiences: a quantitative analysis. J Patient Exp 2018; 5: 97-105.

Hall LH, Johnson J, Watt I, Tsipa A, O'Connor DB. Healthcare staff wellbeing, burnout, and patient safety: a systematic review. PLoS One 2016; https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159015.

Healy S, Tyrrell M. Stress in emergency departments: experiences of nurses and doctors. Emerg Nurs 2011; 19: 31-7.

LeBlanc VR. The effects of acute stress on performance: implications for health professions education. Acad Med 2009; 84(10 Suppl): S25-33.

Barsuk JH, Cohen ER, McGaghie WC, Wayne DB. Long-term retention of central venous catheter insertion skills after simulation-based mastery learning. Acad Med 2010; 85(10 Suppl): S9-12.

Boet S, Borges BC, Naik VN, et al. Complex procedural skills are retained for a minimum of 1 yr after a single high-fidelity simulation training session. Br J Anaesth 2011; 107: 533-9.

Lorello GR, Cook DA, Johnson RL, Brydges R. Simulation-based training in anaesthesiology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth 2014; 112: 231-45.

Lipman S, Carvalho B, Brock-Utne J. The demise of general anesthesia in obstetrics revisited: prescription for a cure. Int J Obstet Anesth 2005; 14: 2-4.

Gordon M, Darbyshire D, Baker P. Non-technical skills training to enhance patient safety: a systematic review. Med Educ 2012; 46: 1042-54.

Balki M, Chakravarty S, Salman A, Wax RS. Effectiveness of using high-fidelity simulation to teach the management of general anesthesia for cesarean delivery. Can J Anesth 2014; 61: 922-34.

Hubert V, Duwat A, Deransy R, Mahjoub Y, Dupont H. Effect of simulation training on compliance with difficult airway management algorithms, technical ability, and skills retention for emergency cricothyrotomy. Anesthesiology 2014; 120: 999-1008.

Fletcher GC, McGeorge P, Flin RH, Glavin RJ, Maran NJ. The role of non-technical skills in anaesthesia: a review of current literature. Br J Anaesth 2002; 88: 418-29.

Karpicke JD, Roediger HL 3rd. The critical importance of retrieval for learning. Science 2008; 319: 966-8.

Siegel LL, Kahana MJ. A retrieved context account of spacing and repetition effects in free recall. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn 2014; 40: 755-64.

Author contributions

Robert ffrench-O’Carroll contributed to interpretation of data and writing and revision of the manuscript. Zahid Sunderani contributed to study conception and design, recruitment of participants, data acquisition, and data entry. Roanne Preston contributed to study design, and writing and revision of the manuscript. Ulrike Mayer contributed to data analysis, interpretation of data, and writing and revision of the manuscript. Arianne Albert contributed to data analysis, interpretation of data, and writing and revision of the manuscript. Anthony Chau contributed to all aspects of this manuscript, including study conception and design; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; and writing and revision of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the operating room nurses at BC Women’s Hospital for participating in this project.

Disclosures

None.

Funding statement

None.

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Dr. Ronald B. George, Associate Editor, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

ffrench-O’Carroll, R., Sunderani, Z., Preston, R. et al. Enhancing knowledge, skills, and comfort in providing anesthesia assistance during obstetric general anesthesia for operating room nurses: a prospective observational study. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 69, 1220–1229 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-022-02277-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-022-02277-2