Abstract

Background and Objectives

Existing generic preference-based measures were all developed in Western countries. Evidence shows that the Chinese population may have different perceptions about health and health-related quality of life. This study aimed at developing a descriptive system of a new generic preference-based measure under the initiative of China Health Related Outcomes Measures (CHROME).

Methods

Qualitative data were collected through semi-structured interviews conducted in-person or online. Respondents were recruited from both the general public and populations with chronic diseases. Open-ended questions about the respondent’s perception of general health and important aspects of health-related quality of life were asked. Probing questions based on a systematic review of existing generic preference-based measures were also used. The framework analysis was used to synthesize the qualitative data. Candidate items for the descriptive system were selected following the ISPOR and COSMIN guidelines. Expert panel review and cognitive debriefings were conducted for further revisions.

Results

Qualitative interviews were conducted among 68 respondents, with 48.5% male and a mean age of 47.8 years (range 18–81 years). In total, 1558 codes were identified and then aggregated to 31 sub-themes and corresponding six themes to inform the development of the initial version of the descriptive system. Feedback from the expert panel survey and meeting (n = 15) and the cognitive debriefing interviews (n = 30) was incorporated into the revised version of the measure. Finally, the generic version of CHROME (CHROME-G) included 12 items across six domains, namely, pain, fatigue, appetite, mobility, vision, hearing, sleeping, daily activities, depression, worry, memory, and social interactions. The descriptive system used a mix of four-level and five-level response options and a 7-day recall period.

Conclusions

The CHROME-G is the first generic preference-based measure to be developed based on the inputs from the Chinese populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Existing generic preference-based measures were all developed in Western countries. There is evidence showing that the Chinese population may have different perceptions about health and health-related quality of life. |

China Health Related Outcomes Measures (CHROME) is an initiative aimed at developing a series of preference-based, health-related quality-of-life instruments to support coverage decision making in China. |

The CHROME-G is the first generic preference-based measure instrument with 12 items developed specifically for China. |

1 Introduction

Economic evaluations of healthcare technologies generate key cost-effectiveness evidence to inform coverage decision making [1, 2]. A cost-utility analysis with the outcome measure of quality-adjusted life-years is recommended in many countries, including China [1, 2]. China’s latest version of economic evaluation guidelines published in 2020 recommends the use of generic preference-based measures (PBMs) in measuring health utilities for quality-adjusted life-years [3]. Instead of recommending a specific instrument, the guidelines prefer the use of the instruments with a value set developed from a representative sample of the Chinese general population [1, 4,5,6]. Currently, among the commonly used generic PBMs are the EQ-5D (including EQ-5D-3L and EQ-5D-5L) and SF-6D (the latest version SF-6Dv2), which have Chinese versions and corresponding value sets available [4,5,6,7].

All existing generic PBMs were developed in Western countries [8, 9]. Evidence shows that the Chinese population might have different perceptions about health and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) compared with people in Western countries [10,11,12]. Socio-cultural adaptation may not fully address this issue [13]. Empirical studies had found inconsistent conceptualization of health domains, insufficient internal consistency, and unsatisfactory item-to-scale correlation when these instruments were used among the Chinese respondents [10, 14, 15]. In the development of new EuroQoL Health and Wellbeing instrument (EQ-HWB) that aims to assess the impact on the health and well-being of care recipients and caregivers [16], the conceptual model was reasonably well confirmed in the UK, Australia, and the USA, but not in China [17, 18]. Moreover, most of the existing generic PBMs were developed decades ago. Important aspects of HRQoL perceived by people may have changed over time. For example, recently developed generic instruments such as AQoL-8D [19] and PROPr [20] place more emphasis on mental and social health [9].

In 2018, China established the National Healthcare Security Administration that reviews submission dossiers and makes centralized coverage decisions for the country [21]. Since then, there has been a growing interest and need in using PBMs specifically developed for China. Therefore, we have created a research program aimed at developing China Health Related Outcomes Measures (CHROME), a system of PBMs developed specifically for China. This paper presents the development of a generic descriptive system under this initiative.

2 Methods

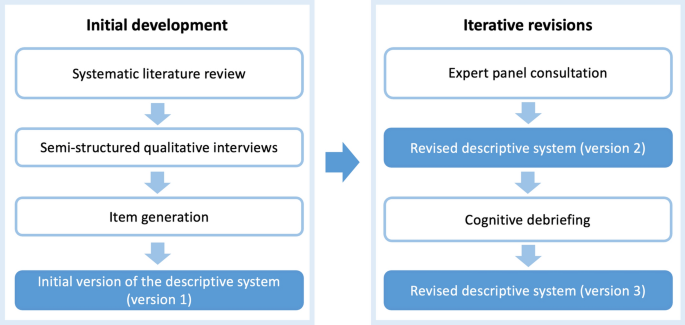

The health definition by the World Health Organization was adopted as the conceptual framework to guide the development of CHROME [22]. Good practice guidelines for developing patient-reported outcome measures from ISPOR were followed [23, 24]. The COSMIN checklist was also followed to ensure compliance with the recommendations on content validity [25,26,27]. Figure 1 shows the steps taken to develop the descriptive system of a generic instrument, the CHROME-G. The study was granted ethical approval by the Academic Ethics Committee at Tianjin University (Reference No. TJUE-2021-168) and the Ethics Committee at Liaoning Institute of Basic Medicine (Reference No. 2020-01-5). Informed consent was obtained from all respondents in this study.

2.1 Step 1: Development of an Initial Version of the Descriptive System

2.1.1 Systematic Literature Review

A systematic literature review was conducted by searching PubMed, Embase, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, and China WanFang Data up to April 2020 to identify all the existing generic PBMs [9]. A total of 18 generic PBMs were identified, including QWB (1976), RKI (1978), EQ-5D-3L (1990), HUI 2 (1992), 15D (1994), LHS (1994), HUI 3 (1995), QLHQ (1995), QWB-SA (1997), AQoL-4D (1997), SF-6Dv1 (1998), EQ-5D-5L (2009), AQoL-6D (2012), AQoL-7D (2012), AQoL-8D (2014), SF-6Dv2 (2015), and PROPr (2017) [9]. The number of dimensions covered by these generic PBMs ranges from 3 to 15, with two to seven response levels. Physical function (18/18), pain and discomfort (17/18), and emotional issues (e.g., depression, anxiety, nervousness, anger) (16/18) are the most covered dimensions in these measures. Ten instruments include dimensions related to social function. Among these 18 generic PBMs, only the EQ-5D-3L, EQ-5D-5L, SF-6Dv1, and SF-6Dv2 have been translated into Chinese versions following standard translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and validation process [9]. The China utility value sets are only available for the EQ-5D-3L, the EQ-5D-5L, and the SF-6Dv2 [4, 5, 7]. The SF-6Dv1 value set is only available for Chinese Hong Kong [28]. All items included in existing generic PBMs were extracted and grouped into physical, mental, and social domains according to the health definition by the World Health Organization, and then used as probing questions for the qualitative interviews (see Appendix 2 in the Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM]).

2.1.2 Qualitative Interview

By following the COSMIN guidelines, the semi-structured interview guide (Appendix 1 in the ESM) was developed and tested with seven respondents (including two from the CHROME study group and five from the general public) [27]. Two interviewers received 1-day training on how to use the interview guide, and communicate and interact with respondents during the interview. Then, they completed three pilot interviews under the supervision of principal investigators before the formal interviews. The two interviewers completed all the interviews in person or using the online platform based on the preference of the respondents. Respondents were eligible to participate in this study if they were aged 18 years or older; had Chinese nationality; had lived in China for the past 5 years; were able to read and communicate in Chinese; and were without cognitive impairment. A quota sampling framework in terms of age, sex, education, and area of urban/rural residence was used to recruit a representative sample of respondents from the Chinese general public (Table 1) [29]. In addition, a purposeful sampling approach was also used to recruit respondents with any of the top 15 prevalent chronic diseases in China as reported by the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study 2017 (Table 1) [30].

After the demographic information was collected, the interview then started with open-ended questions about the respondent’s general health and what aspects of health and HRQoL were considered important to them. The questions included in existing generic PBMs identified from the literature review were used to probe the respondent only if the total time spent on answering all the open-ended questions was less than 10 minutes or the respondents mentioned less than two different aspects for each of the open-ended questions [9]. In the end, each respondent can raise any question or issue that was not discussed during the interview.

The interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed immediately after completion. The total sample size was determined by reaching content saturation at the sub-theme level (described below) as well as within subgroup defined by age, sex, education, and area of urban/rural residence, which was defined as the point when no new information was provided by the five consecutive respondents [23]. Qualitative analysis software NVivo v11.0 (QSR International Pty. Ltd, Melbourne, VIC, Australia) was used to manage and analyze the qualitative data.

2.1.3 Development of an Initial Version of the Descriptive System

A qualitative framework analysis was used to organize and synthesize data into the analytical structure [31,32,33]. It comprised five stages: familiarization, coding, indexing, charting, and mapping/interpretation [31,32,33]. Briefly, the two interviewers read all transcripts, extracted an initial set of codes, and grouped the codes into code categories to develop an a priori analytic framework. The coders then applied the analytic framework to collate respondents’ quotes under the agreed code categories. Inductive emergent codes were added to the framework as required. Then, the coders summarized all the codes into a matrix with one row per respondent and one column per code category, and each cell containing summaries of related codes. Code categories were then aggregated into sub-themes, which were subsequently grouped into themes. The aggregation process was conducted by reviewing the concept of health defined by the World Health Organization and the construction of domains of existing generic PBMs and HRQoL measures [9, 13, 22]. The analytic framework was then refined and finalized by examining discriminations in each aggregation level (code, code category, sub-theme, theme). The finalized analytic framework was used to inform the development of the descriptive system.

Candidate items for the descriptive system were selected from all sub-themes formed through a deliberation and consensus process among all investigators after a series of team meetings. Seven graduate students who were not involved in the literature review and the interview process were also invited to attend the team meetings to discuss their feedback on each item. The team deliberated on each candidate item, in light of all codes related to this item, by following the ISPOR and COSMIN principles [23,24,25,26,27, 34]: (1) capturing the constructs measured by the instrument under development; (2) relevant to all members of the target population; (3) worded in a clear manner and consistent with the expressions used by the target population; (4) measuring a single construct, rather than a multi-dimensional concept; (5) not likely to be prone to the ceiling or floor effects within the target population; (6) appropriate for the recall period; and (7) appropriate for self-reporting. A candidate item was included/excluded in the initial version of the descriptive system if there was a consensus among the team. If there was no agreement after the team deliberation, a formal voting process among 15 team members (including eight investigators listed as authors and seven graduate students) was used with a two-thirds majority rule. An initial version of the descriptive system (version 1) was therefore developed (Table 2).

2.2 Step 2: Iterative Revisions of the Descriptive System

2.2.1 Consultation with the Expert Advisory Panel

An expert advisory panel comprising national experts in health economics and outcome measures was formed and invited to comment on each candidate item included in the initial version of the descriptive system through an online survey. The experts were also asked to rank the level of severity of candidate response levels for each item on a rating scale, on which 0 presents the least severe and 10 the most severe. The candidate response levels were identified from the qualitative interviews. Any further comments on the descriptive system were also collected. Descriptive summary statistics (frequency, proportion, mean, and standard deviation [SD]) were used to analyze the expert feedback. A half-day online expert panel meeting was then held to present the descriptive results of each item and discuss the issues raised during the online survey. The descriptive system was revised according to the consensus achieved during the panel meeting (version 2) (Table 2).

2.2.2 Cognitive Debriefing

The revised version was further tested through a face-to-face cognitive debriefing interview with a group of respondents from the generic public who had not participated in the qualitative interviews. All cognitive debriefing interviews were conducted by the same two interviewers. The objective of the debriefing interview was to ensure that the contents of the descriptive system and corresponding instructions, recall period, and response options, were relevant, comprehensive, and understandable [24, 25]. The interview guide for the cognitive debriefing can be found in Appendix 3 in the ESM. Purposeful sampling was employed to maximize the variation in the demographic characteristics, including age, sex, education level, and area of residence (urban/rural) among the respondents (Table 1). Respondents were recruited from five cities across mainland China (Tianjin, Nanjing, Xi’an, Chengdu, and Fuzhou), which represent different geographical locations and levels of economic development across the country. Each respondent was asked to first complete the instrument. Then, the interviewer went over each item with the respondent to ensure that the item is appropriate, relevant, and easy to understand and answer. The descriptive system was further modified and finalized (version 3) (Table 2). A psychometric validation study is ongoing.

3 Results

3.1 Step 1: Initial Development of the Descriptive System

A total of 68 respondents, including 40 respondents from the general public and 28 with 15 pre-selected chronic diseases, were interviewed between May and November 2020. Content saturation was reached after 63 interviews. Among 68 respondents, 48.5% were male with a mean (SD) age of 47.8 (17.3) years (range 18–81 years) and with 61.8% living in an urban area. The demographic characteristics of the respondents are reported in Table 1. The residence locations of the respondents covered all 31 provinces of mainland China (Appendix 5 in the ESM). Ten (14.7%) interviews were conducted face to face and the rest online because of the public health policy of COVID-19 in China. The mean (SD) duration of the interview was 34.9 (6.2) minutes, with a range of 18.4–54.3 minutes. Twenty (29.4%) respondents whose initial responses to the open-ended questions were too short or limited were further probed using the items identified from the review of existing generic PBMs.

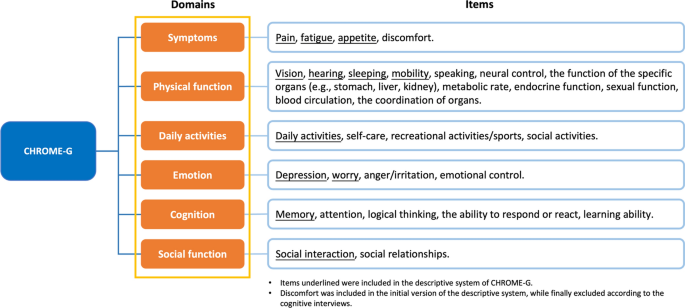

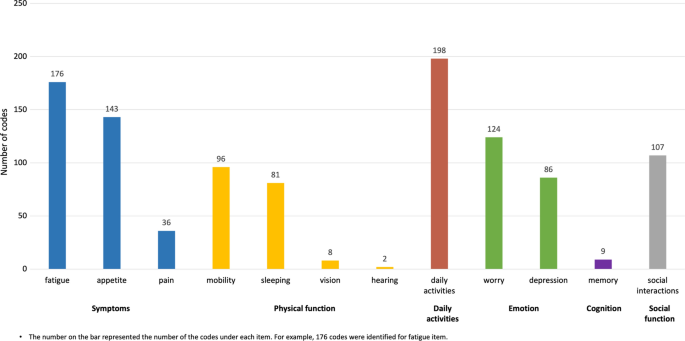

The process of the framework analysis identified 1558 unique codes across 129 code categories, which were subsequently grouped into 31 sub-themes and six themes (Fig. 2). Among 1558 codes, 207 codes were identified as a result of the probing questions but did not lead to the generation of new code categories. Codes related to two non-health-related themes were excluded, namely, well-being (codes related to the personal attitude towards life, e.g., freedom, satisfaction, disappointment, loneliness, jealousy, and repentance) and background (codes related to the individual character or environmental background, e.g., life rules/habits, self-discipline, social and financial status, income and consumption level, ecological environment, and political environment).

According to the consensus among the team based on the seven principles described above (Appendix 4 in the ESM), 13 sub-themes formed the candidate items and correspondingly six themes were used to form the domains for the development of the initial version of the descriptive system of CHROME-G, namely, pain, discomfort, fatigue, appetite, mobility, vision, hearing, sleeping, daily activities, depression, worry, memory, and social interaction (Fig. 2). The number of codes and corresponding code categories identified for each candidate item is reported in Fig. 3. Each candidate item included in the initial version of the instrument is also briefly described below.

3.2 Symptoms

3.2.1 Pain

There were 36 codes related to pain, which vary in terms of body location (e.g., head, arm, stomach, tooth, back, chest, knee), type (e.g., dull, sore, ache, sharp), intensity (e.g., mild, moderate, severe, unbearable), and frequency (e.g., constant, intermittent). An item asking the severity of general pain was included.

3.2.2 Discomfort

Discomfort refers to any symptom other than the pain experienced by the respondents. Across the identified 111 codes, the discomfort may include naupathia, emesis, numbness, stiffness, and itch, usually along with the specific locations (e.g., heart, ear, chest, throat). A general question asking about the severity of discomfort was included.

3.2.3 Fatigue

One hundred and seventy-six codes related to fatigue were identified, which was one of the most frequently mentioned by the respondents. Respondents frequently described two types of fatigue: physical and mental. Physical fatigue was described as “lacking physical power,” “weak,” “anile,” “exhausted,” or “just want to lie down and don’t want to move at all”; and mental fatigue as “depleted of energy,” “dizzy,” “distracted,” and “no enthusiasm for anything”. An item on the severity of fatigue was developed based on these codes.

3.2.4 Appetite

Most respondents mentioned that appetite is an important aspect affecting their health and quality of life, with 143 codes identified. These codes mainly reflected two aspects related to appetite, the desire for food (e.g., “I don’t feel hungry all day,” “I don’t want to eat anything,” “nothing tastes good”) and the amount of food taken (e.g., “I just eat a little and I feel full,” “I eat a lot less than usual”). Some respondents also mentioned that appetite was also affected by mental aspects (e.g., “I always overeat when I feel sad,” “I don’t want to eat anything when I’m stressed,” “I won’t eat if I make a mistake during my work”), and physical aspects (e.g., “I can’t eat anything when my leg feels painful,” “I don’t want to eat if I don’t sleep well”). An item asking about the desire for food was included in the initial version of the measure.

3.2.5 Physical Function

3.2.5.1 Mobility

Being able to walk was important and frequently mentioned by the respondents with 96 codes identified. A question asking the difficulty of walking was therefore included.

3.2.5.2 Sleeping

There were 81 codes related to sleeping. Most respondents reported the importance of the duration and quality of sleep, including difficulties with falling asleep, a relatively short period of deep sleep, and particularly staying up late. Some respondents also mentioned that sub-optimal sleep at night often resulted in daytime fatigue and they needed a nap during the day. Thus, a question asking about the quality of sleeping was included.

3.2.5.3 Vision

Despite a small number of codes related to vision (n = 8), it seems that some respondents mentioned that vision is critical to their quality of life by stating that, for example, “you can’t do anything without your eyes” and “I can’t look after myself if I have a severe visual impairment”. We thus included a question asking about problems with vision in the initial version.

3.2.5.4 Hearing

Similar to vision, hearing was an important function for maintaining good health and quality of life among a few respondents who stated, “when you can’t hear the sound, you can’t feel anything” and “it feels terrible when your family tells you that the TV is too loud, but you can’t hear anything”. A question asking about problems with hearing was used.

3.2.6 Daily Activities

One hundred and ninety-eight codes were identified for daily activities, which resulted in the most frequently mentioned item. Most respondents described the restrictions on daily activities they encountered that have a significant impact on their HRQoL. Common experiences were being unable to do chores, participate in activities with family and friends, or work. Some respondents mentioned daily activities in a positive way, i.e., some recreational activities could bring positive effects on HRQoL. Role continuity was also raised by some respondents, with daily activities linked to previous roles and hobbies helping to maintain their identity. A general question asking how difficult it was to do daily activities was included.

3.2.7 Emotion

3.2.7.1 Depression

Eighty-six codes were identified to describe depression (e.g., “depressed,” “feel awful,” “upset,” “overwhelmed”). Some respondents mentioned that these feelings were linked to having certain diseases or symptoms, while some other respondents mentioned experiencing depression because of the stress from working, studying, or family. A general question asking about the severity of depression was included.

3.2.7.2 Worry

According to the 124 codes identified, the majority of respondents discussed how their feeling of worry affect their HRQoL, albeit with different descriptions (e.g., “nervous,” “tense,” “strained,” “uptight,” “anxious”). Other instances were related to interpersonal relationships, self-identification, and the trifles of life. A few respondents mentioned that the feeling of worry might have a positive impact on their HRQoL, such as appropriate pressure could lead to stronger motivation and higher productivity at work. A general question on the severity of worry was used.

3.2.8 Cognition

The majority of respondents gave some examples of forgetfulness during the conversation, difficulties in remembering the location of items, and the time of taking medications. This is common and may be experienced daily. Therefore, a general question asking about memory was included.

3.2.9 Social Function

There were 107 codes related to social interactions, including communicating with friends and family, and playing roles at work and community. They emphasized that these experiences had a non-negligible impact on their own health. A question asking about the extent of the impact of health on social interactions was employed.

For the response levels of the items described above, two response options were identified during the development process. One is five response levels indicating no, mild, moderate, severe, and extreme problems. However, for some items, respondents reflect that it is difficult to differentiate between severe and extreme levels. Therefore, an alternative option with four response levels indicating no, mild, moderate, and severe problems was created and tested.

3.3 Step 2: Iterative Revisions of the Descriptive System

A total of 15 experts including six health economists, four quality-of-life researchers, and two each of clinical experts and healthcare decision makers were invited and completed the online survey and attended the panel meeting. The panel suggested minor wording changes to items asking about fatigue and sleeping. The panel also considered the meaning of the discomfort item was too vague to be measurable, and thus suggested testing it in cognitive debriefing interviews. In addition, they reached a consensus that two alternative versions of the descriptive system, one using “today” and the other “in the past 7 days” as the recall period, be tested in the cognitive debriefing (Table 2).

Thirty respondents recruited from the general public participated in in-person cognitive debriefing interviews conducted from July to September 2021. Of the respondents, 53.3% were male with a mean (SD, range) age of 49.8 (17.7, 18–82) years. The mean (SD) duration of the interviews was 24.7 (10.8) minutes, with a range of 10.6–60.1 minutes. Characteristics of the respondents in the cognitive debriefing are presented in Table 1.

Cognitive debriefing respondents found that overall the items are relevant, comprehensive, and easy to understand and complete. The respondents suggested using the past 7 days as the recall period, and some minor wording changes to pain, fatigue, appetite, sleeping, depression, and social interactions for easier understanding. In addition, based on the feedback from the respondents and team discussions, the discomfort item was removed based on two considerations. First, the respondents reflected that the discomfort item was too vague to answer. Second, some respondents reported that without any specification about discomfort, they often think about bodily pain or fatigue, which are already included in the instrument. This was confirmed by re-reviewing the interview transcripts that show that discomfort was often mentioned together with pain or fatigue.

The cognitive debriefing interviews resulted in the final 12 items from six domains for the descriptive system of the CHROME-G. These items are pain, fatigue, appetite, mobility, vision, hearing, sleeping, daily activities, depression, worry, memory, and social interactions. Four-level response options are used for all items except for mobility, daily activities, appetite, and sleeping, for which a fifth level “unable to” is added. The recall period of “the past 7 days” is selected for the descriptive system (Table 2).

4 Discussion

The goal of the CHROME initiative is to develop a series of preference-based instruments specifically for China. In this paper, we describe the development of a generic descriptive system, the CHROME-G, under this initiative. This generic instrument covers a range of domains and items of HRQoL perceived as important by the Chinese population, such as appetite, sleeping, fatigue, vision, hearing, and memory, which have not been included in any of the three generic PBMs that are currently used in China. The CHROME-G is the first PBM developed in China. The validation and valuation of the CHROME-G are ongoing. Once completed, the CHROME-G can be used to measure HRQoL and estimate quality-adjusted life-years for economic evaluations and health technology assessments, and subsequently support coverage decision making in China.

Existing generic PBMs were all developed in Western countries and evidence had consistently revealed the difference in important aspects of HRQoL perceived by the Chinese population compared with people in Western countries [10,11,12,13]. In addition, most of these existing PBMs were developed decades ago. Perceptions on important aspects of HRQoL may change over time [9, 35, 36], which motivated, in part, the recent development of new instruments, both generic and disease specific, in Western countries [17, 20, 37, 38]. Compared with existing generic PBMs, a unique item in the CHROME-G is appetite. In Chinese culture, the desire for food is considered one of the most important indicators for good health and quality of life. In China, people greet each other with “have you eaten yet?”. There is an idiom in Chinese, “bread always comes first”. Previous studies conducted in China also identified appetite as an important aspect of HRQoL [11, 13]. The eating item is included in the 15D [39]. However, the item focuses on the eating function with the response varying from “I am able to eat normally, i.e., with no help from others” to “I am unable to eat at all, so I am fed either by tube or intravenously”. In contrast, the appetite item in the CHROME-G measures the desire for food with response levels from “normal” to “I have no desire for food at all”. This item was identified as an important aspect of quality of life among Chinese population during both qualitative and cognitive debriefing interviews.

Items of sleeping and fatigue included in this study were only included in 15D, AQoL, and PROPr [9, 20, 40]. Similarly, both vision and hearing items were also only included in a few existing generic PBMs, for example, HUI, 15D, and AQoL [9, 40]. The memory item was only included in PROPr as an independent dimension among existing generic PBMs. However, a previous study also found that these items have been frequently linked with the concept of health in the Chinese literature [15]. Therefore, notable gaps in these dimensions could be observed in some of the commonly used measures, such as EQ-5D, SF-6D, QWB-SA, and HUI3 [9, 40, 41]. However, it is worth noting that some explorations, such as bolt-on studies for EQ-5D, have been conducted to cover this gap of missing dimensions that are important for describing HRQoL [42, 43].

Results of the literature review and qualitative interviews in this study also indicate potential disparities in health preferences between Chinese and Western populations. Compared with Western populations, the Chinese population places more importance on physical health, self-care, and daily activities, but relatively less attention to mental and social health [11, 13]. This disparity could also be demonstrated in the value sets of the EQ-5D-5L and the SF-6Dv2. The utility decrement of the dimensions related to physical health (e.g., physical functioning and pain dimensions in the SF-6Dv2 and mobility and pain/discomfort dimensions in the EQ-5D-5L) was the largest in the Chinese value sets, while those value sets for Western countries have a larger utility decrement for mental health dimensions [7]. One possible reason is that the Chinese population is less willing to talk about mental health issues openly, possibly because of the Chinese culture, in which there is a social stigma towards people with mental health issues [15]. For social function, many may perceive it has only a relatively remote relationship with health [7].

There are a few aspects of HRQoL included in existing generic PBMs also perceived as important in China. For example, pain, mobility, depression, and worry are included in almost all the existing generic PBMs [9, 40, 44]. Evidence from previous studies has shown such similarities [13, 15]. Most PBMs also measure daily activities but differently. For example, both the EQ-5D and 15D measure usual activities [39, 45]; while SF-6Dv2 has one item measuring different intensities of activities [46]. Social function is only included in a few generic PBMs such as the social activity item in the QWB-SA and social functioning in the SF-6Dv2 [46, 47], whilst a broader concept, including satisfaction of a close relationship, feeling socially isolated, and role in the community, is included in the AQoL-8D [19]. Sleeping and fatigue are included in the 15D, the AQoL, and the PROPr [9, 20, 39, 40]. Both vision and hearing are included in the HUI, the 15D, and the AQoL [9, 40], while memory is only included in PROPr [20]. It is also worth noting that no existing generic PBM covers most of the CHROME-G items in a single instrument [9], which provides strong evidence supporting the development of China’s own instrument.

There is a wide range of recall periods adopted in existing generic PBMs, for example, “today” by the EQ-5D and 15D [39, 45], “the last 3 days” by the QWB-SA [47], “the past week” by the AQoL-8D [19], and “the past 4 weeks by the SF-6D [46,47,48]. However, little is known of how these recall periods were selected [9]. In our interviews, respondents reflected that focusing on a point in time (e.g., “today”) can hardly capture the true status of their health. Using the recall period of 7 days is less ambiguous and can fairly and accurately reflect their present health. The respondents also prefer “the past 7 days” to “the last week” as the latter may be interpreted differently across individuals (e.g., the week preceding the current one vs the past 5 days or 7 days). This may unnecessarily introduce the between-respondent variation.

The strengths of this study are worth noting. First, the respondents were recruited from all 31 provinces in China. Involving people from the general public and with chronic diseases in the development of the CHROME descriptive systems ensures the study captures the most important aspects of HRQoL perceived by the Chinese population. Second, conducting qualitative interviews and cognitive debriefings among the general population helps choose proper wordings that can be easily understood without the need for additional explanation. One such example is asking about depression for which the Chinese versions of existing PBMs use the direct translation. However, this direct translation of depression usually uses a medical term that is not commonly used in the oral language, and thus may not be easily understood by the general public in China [49]. For example, based on the feedback from the respondents, the CHROME-G uses “feeling down” to describe the emotional impact related to depression. Similarly, the item asking about the severity of “feeling worried” was used in the CHROME-G instead of “anxiety” used in the Chinese versions of existing PBMs. Third, the content saturation was reached at the sub-theme level as well as within the subgroups defined by age, sex, education, and area of urban/rural residence. The correspondingly large sample size for qualitative interviews ensured that the views and preferences on HRQoL among the Chinese population were comprehensively extracted.

Our study has several limitations. First, because of the COVID-19 pandemic, some areas in China had strict controlling measures, thus we had to switch to online interviews for some respondents. The interaction through an online platform may not be as personal and efficient as seen in the face-to-face interview. Second, we used purposeful sampling when recruiting respondents with pre-selected health conditions. The main purpose of engaging people with chronic conditions was to obtain their inputs as opposed to achieving a representative sample for this population. Third, the sample size for this group was small and does not cover all prevalent chronic diseases. Fourth, although the proportion of non-Han ethnic groups in qualitative interviews was comparable to that of the Chinese general population (7.3% vs 8.4%), the number of non-Han respondents was small. We could not recruit some ethnic groups because of feasibility or other practical challenges.

5 Conclusions

The CHROME-G is a new generic preference-based HRQoL instrument that was developed based on the inputs from the general public and people with chronic health conditions. The 12-item instrument is the first PBM developed specifically for China.

References

Brazier J, Ratcliffe J, Saloman J, Tsuchiya A. Measuring and valuing health benefits for economic evaluation. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2017.

Neumann PJ, Sanders GD, Russell LB, Siegel JE, Ganiats TG. Cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. 2nd ed. New York (NY): Oxford University Press; 2016.

Liu GG, Hu S, Wu JH, Wu J, Dong C, Li H. China guidelines for pharmacoeconomic evaluations (2020). Beijing: China Market Press; 2020.

Liu GG, Wu H, Li M, Gao C, Luo N. Chinese time trade-off values for EQ-5D health states. Value Health. 2014;17:597–604.

Luo N, Liu G, Li M, Guan H, Jin X, Rand-Hendriksen K. Estimating an EQ-5D-5L value set for China. Value Health. 2017;20:662–9.

Wu J, Xie S, He X, Chen G, Brazier JE. The simplified Chinese version of SF-6Dv2: translation, cross-cultural adaptation and preliminary psychometric testing. Qual Life Res. 2020;29:1385–91.

Wu J, Xie S, He X, Chen G, Bai G, Feng D, et al. Valuation of SF-6Dv2 health states in China using time trade-off and discrete-choice experiment with a duration dimension. Pharmacoeconomics. 2021;39:521–35.

Guillemin F, Bombardier C, Beaton D. Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: literature review and proposed guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:1417–32.

Xie S, Chen P, He X, Wu J, Xie F, Zhao K. Review of generic preference-based scales for health-related quality of life around the world. Chinese J Health Policy. 2020;13:58–68.

Cnossen MC, Polinder S, Vos PE, Lingsma HF, Steyerberg EW, Sun Y, et al. Comparing health-related quality of life of Dutch and Chinese patients with traumatic brain injury: do cultural differences play a role? Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15:72.

Mao Z, Ahmed S, Graham C, Kind P. The unfolding method to explore health-related quality of life constructs in a Chinese general population. Value Health. 2021;24:846–54.

Bowden A, Fox-Rushby JA. A systematic and critical review of the process of translation and adaptation of generic health-related quality of life measures in Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, South America. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:1289–306.

Mao Z, Ahmed S, Graham C, Kind P, Sun Y-N, Yu C-H. Similarities and differences in health-related quality of life concepts between the East and the West: a qualitative analysis of the content of health-related quality of life measures. Value Health Reg Issues. 2021;24:96–106.

Hill MR, Noonan VK, Sakakibara BM, Miller WC, Team SR. Quality of life instruments and definitions in individuals with spinal cord injury: a systematic review. Spinal Cord. 2010;48:438–50.

Mao Z, Ahmed S, Graham C, Kind P. Exploring subjective constructions of health in China: a Q-methodological investigation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18:165.

EQ-HWB. Blog: EQ-5D. https://euroqol.org/blog/eq-hwb/. Accessed 13 Mar 2022.

Brazier J, Peasgood T, Mukuria C, Marten O, Kreimeier S, Luo N, et al. The EQ health and wellbeing: overview of the development of a measure of health and wellbeing and key results. Value Health. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2022.01.009.

Peasgood T, Mukuria C, Brazier J, Marten O, Kreimeier S, Luo N, et al. Developing a new generic health and wellbeing measure: psychometric survey results for the EQ health and wellbeing. Value Health. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2021.11.1361.

Richardson J, Iezzi A, Khan MA, Maxwell A. Validity and reliability of the Assessment of Quality of Life (AQoL)-8D multi-attribute utility instrument. Patient. 2014;7(1):85–96.

Hanmer J, Cella D, Feeny D, Fischhoff B, Hays RD, Hess R, et al. Selection of key health domains from PROMIS® for a generic preference-based scoring system. Qual Life Res. 2017;26:3377–85.

National Healthcare Security Administration. http://www.nhsa.gov.cn/. Accessed 9 Mar 2022.

World Health Organization (WHO). Constitution of the World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/gb/bd/pdf_files/BD_49th-en.pdf#page=6. Accessed 9 Mar 2022.

Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, Leidy NK, Martin ML, Molsen E, et al. Content validity: establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO Good Research Practices Task Force Report: part 1: eliciting concepts for a new PRO instrument. Value Health. 2011;14:967–77.

Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, Leidy NK, Martin ML, Molsen E, et al. Content validity: establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO Good Research Practices Task Force Report: part 2: assessing respondent understanding. Value Health. 2011;14:978–88.

Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL, et al. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:539–49.

Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL, et al. The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:737–45.

COSMIN. COSMIN methodology for assessing the content validity of PROMs. https://www.cosmin.nl/wp-content/uploads/COSMIN-methodology-for-content-validity-user-manual-v1.pdf. Accessed 9 Mar 2022.

Lam CLK, Brazier J, McGhee SM. Valuation of the SF-6D health states is feasible, acceptable, reliable, and valid in a Chinese population. Value Health. 2008;11:295–303.

National Bureau of Statistics of China. China statistical yearbook 2019. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2019/indexeh.htm. Accessed 9 Mar 2022.

James SL, Abate D, Abate KH, Abay SM, Abbafati C, Abbasi N, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392:1789–858.

Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Huberman AM, Miles MB, editors. The qualitative researcher’s companion. London: Routledge; 1994. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412986274.

Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:117.

Furber C. Framework analysis: a method for analysing qualitative data. Afr J Midwifery Womens Health. 2010;4:97–100.

Brod M, Tesler LE, Christensen TL. Qualitative research and content validity: developing best practices based on science and experience. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:1263.

Spolak-Bobryk N, Niedoszytko M, Jassem E, Chełmińska M, Lange M, Majkowicz M, et al. Assessing quality of life in patients with mastocytosis: development of the disease-specific questionnaire. Postȩpy Dermatol Alergol. 2021;38:1044–51.

Paradowski PT, Englund M, Lohmander LS, Roos EM. The effect of patient characteristics on variability in pain and function over two years in early knee osteoarthritis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3:59.

Rowen D, Brazier J, Ara R, Zouraq IA. The role of condition-specific preference-based measures in health technology assessment. Pharmacoeconomics. 2017;35:33–41.

Goodwin E, Green C. A systematic review of the literature on the development of condition-specific preference-based measures of health. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2016;14:161–83.

Sintonen H. The 15D instrument of health-related quality of life: properties and applications. Ann Med. 2001;33:328–36.

Brazier J, Ara R, Rowen D, Chevrou-Severac H. A review of generic preference-based measures for use in cost-effectiveness models. Pharmacoeconomics. 2017;35:21–31.

Efthymiadou O, Mossman J, Kanavos P. Health related quality of life aspects not captured by EQ-5D-5L: results from an international survey of patients. Health Policy. 2019;123:159–65.

Finch AP, Brazier JE, Mukuria C. Selecting bolt-on dimensions for the EQ-5D: examining their contribution to health-related quality of life. Value Health. 2019;22:50–61.

Yang Y, Rowen D, Brazier J, Tsuchiya A, Young T, Longworth L. An exploratory study to test the impact on three “bolt-on” items to the EQ-5D. Value Health. 2015;18:52–60.

Finch AP, Brazier JE, Mukuria C. What is the evidence for the performance of generic preference-based measures? A systematic overview of reviews. Eur J Health Econ. 2018;19:557–70.

Group TE. EuroQol: a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208.

Brazier JE, Mulhern BJ, Bjorner JB, Gandek B, Rowen D, Alonso J, et al. Developing a new version of the SF-6D health state classification system from the SF-36v2: SF-6Dv2. Med Care. 2020;58:557–65.

Kaplan RM, Sieber WJ, Ganiats TG. The quality of well-being scale: comparison of the interviewer-administered version with a self-administered questionnaire. Psychol Health. 1997;12:783–91.

Brazier J, Usherwood T, Harper R, Thomas K. Deriving a preference-based single index from the UK SF-36 Health Survey. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1115–28.

Yang F, Jiang S, He X, Li H, Wu H, Zhang T, et al. Do rural residents in China understand EQ-5D-5L as intended? Evidence from a qualitative study. Pharmacoecon Open. 2021;5:101–9.

Acknowledgements

We thank the inputs from the expert advisory panel members (listed in alphabetical order): Drs. Gang Chen (Monash University, Australia), Siting Feng (Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University, China), Haijing Guan (Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University, China), Yawen Jiang (Sun Yat-sen University, China), Xuejing Jin (Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, China), Hongchao Li (China Pharmaceutical University, China), Shunping Li (Shandong University, China), Bin Wu (Renji Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiaotong University, China), Hongyan Wu (Guizhou Medical University, China), Hongwei Yang (China National Health Development Research Center, China), Lian Yang (Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, China), Jun Zhang (Liaoning Institute of Basic Medicine, China), Tiantian Zhang (Jinan University, China), Yun Zhang (Fuwai Hospital, The Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, China), and Wentao Zhu (Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, China).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 72174142). The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflicts of interest/competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Ethics approval

The study was granted ethical approval by the Academic Ethics Committee at Tianjin University (Reference No. TJUE-2021-168) and the Ethics Committee at Liaoning Institute of Basic Medicine (Reference No. 2020-01-5), and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Participants were informed about their freedom of refusal. Anonymity and confidentiality were maintained throughout the research process.

Consent for publication

Informed consent for publication was obtained from all individual participants. Participants were informed about their freedom of refusal for data publication. Anonymity and confidentiality were maintained in this publication.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

Concept and design: JW, KZ, and FX. Acquisition of data: JW, XH, PC, XL, and KZ. Analysis and interpretation of data: JW, XH, PC, SX, XL, HH, KZ, and FX. Drafting of the manuscript: JW, XH, PC, SX, and FX. Statistical analysis: JW, XH, PC, SX, and FX. Obtaining funding: JW, KZ, and FX. Supervision: JW, KZ, and FX. All authors critically reviewed previous versions of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, J., He, X., Chen, P. et al. China Health Related Outcomes Measures (CHROME): Development of a New Generic Preference-Based Measure for the Chinese Population. PharmacoEconomics 40, 957–969 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-022-01151-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-022-01151-9