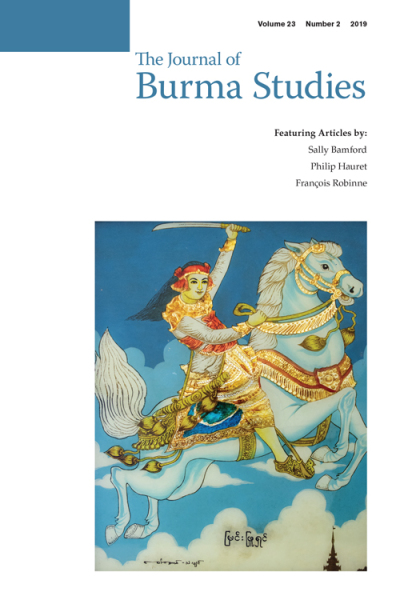

Front Cover:

Myin Phyu Shin. Reverse Glass Painting, c.1990. BC2017.01.15, L 19 1/4” xW 15 1/4”. Gift of the Shwedagon Collection to the Burma Art Collection, Northern Illinois University.

The illustration on the cover is a reverse glass painting of Myin Phyu Shin or the “Lord of the White Horse”, a popular nat or spirit throughout Burma. He is pictured riding his battle mount while holding the reins with his left hand and raising a sword with his right as he launches an attack against an unseen enemy. The horse flies through a cloudy sky above the roofs of the nineteenth-century royal city of Mandalay (visible at the lower left). Viewed as a patron of the army, he is dressed in the princely style of the Konbaung dynasty. The young army officer also wears a red hat, typical of the nats

His legends are varied. Bénédicte Brac de La Perrière identified at least four in Les Rituels de Possession en Birmanie (1989), where R.C. Temple in his The Thirty Seven Nats (1906) associated him as Aung Zwamagyi, “Number 10” in the list of 37 nats, according to the old list he found in the Mahagita Medanigyan.

In one legend, Aung Zwamagyi was a cavalry officer serving Narapathisithu, the CrownPrince. Both were sent by the King of Bagan to suppress a rebellion. But in fact, the King wanted to get access to Narapathisithu’s wife. When Narapathisithu learned of the King’s intentions, he sent Aung Zwamagyi to kill the king, promising that he could marry the widowed queen if he succeeded. But when he succeeded, the queen refused to marry someone outside of royal descent. Aung Zwamagyi flew into a rage and spoke most intemperately. Narapathisithu, now King, summarily executed him for insubordination, and there he became a nat. To appease his spirit, a dedicated altar was established in Kani—a small village in upper Burma—where another legend indicates that he drowned along with his horse, and where a ritual is still celebrated annually.

Myin Phyu Shin belongs to the Pantheon of the 37 and is associated with the ritual of the 37 nats where a wooden sculpture figures him on the altar. He is also represented in households as a horse puppet in domestic altars. In the mid 1950’s, when mass printing became affordable, reproductions of nats became accessible to devotees. They either purchased a color-offset lithography mounted on cardboard or a reverse glass painting, which lasted longer, such as the one adorning the cover of this issue.

– Catherine Raymond, Curator, Burma Art Collection at Northern Illinois University