Title: Epidural Hematoma

Author: Rahaf AlFukaha

Scientific editor: Dr. Omar Jbarah

Linguistic Editor: Zain Alsaddi, Philip Sweidan

Overview:

An epidural hematoma (EDH) is an extra-axial blood accumulation within the space between the inner table of the skull and the dura mater which is the outermost layer of the meninges. (1) It takes a biconvex lenticular shape due to the dura’s adherence to the calvarium, thus not allowing the blood collection to move across sutures.

Intracranial epidural hematomas make up about 1% of all head trauma injuries (2), and while that might seem rather uncommon, they should be taken seriously when evaluating a serious head injury, as they can be fairly life-threatening if not dealt with immediately and appropriately. EDHs are more common in the young adults age group, 20 to 30 year-olds being the most prone (3) as the dura is not yet heavily attached to the calvarium at this age. And studies showed that its more common in men than women. (1)

Etiology and Pathophysiology:

An epidural hematoma is mainly caused by a traumatic injury to the head, like accidental falls (30%), physical abuse (8%), or a motor vehicle crash (53%) (4), but on rare occasions, it could also be due to non-traumatic events such as sinusitis, coagulation disorders, dural metastasis, vascular malformations of the dura, hemorrhagic tumors (5)(6), and very rarely, Langerhans cell histiocytosis (7).

The blood collection in epidural hematomas is mostly from an arterial origin, specifically the middle meningeal artery, seeing as almost all the cases of epidural hematomas are largely associated with a fractured skull (approximately 75% in children and 91% in adults), (8) this in turn usually causes a direct tear in the middle meningeal artery due to its close proximity to the dura mater and the table of the skull, with the pterion being the most common site of rupture. In addition to the arterial origin, blood could come from lacerated dural venous sinuses or the middle meningeal vein, though it is less common, accounting to up to 32% in both children and adult age groups. (9) The most common locations an epidural hematoma could manifest in are the temporal or the temporoparietal region if it was an arterial EDH, and the posterior cranial fossa if it was a venous EDH, (10) with the right side being more predominant than the left side. A previous study done in 1999 showed that 2 to 5% of patients presented with bilateral epidural hematomas. (11)

Epidural hematomas can also occur at the spinal level, and similarly to intracranial epidural hematomas, they could be due to traumatic, and non-traumatic conditions like arterio-venous malformations of the epidural plexus, spinal tumors, hemangiomas, or systemic disease with a high risk of bleeding. (12)(13) This entity is called a spinal epidural hematoma, and it is a rare condition that presents with acute back pain at the site of bleeding with radiation to the extremities with probability of Neurological deficits. (14)

Another type of epidural hematomas is the heat hematoma which is usually seen in burned bodies. It is caused by thermal burns which cause contraction and peeling of the dura mater from the skull and then, excretion of the blood from the venous sinuses. Contrary to blunt trauma epidural hematomas, heat hematomas are crescent shaped, similar to subdural hematomas, and they occur in any intensely burned area, regardless of suture lines. (15)

Clinical Presentation and Complications:

Patients with epidural hematomas have a classical presentation of initial loss of consciousness right after the impact, followed by a lucid interval period of several hours (16) in which there’s a temporary recovery of consciousness with complete or partial return of neurological status. It is fair to mention that, according to a case study in 1984, 21% of patients with EDHs come with the classical presentation of the lucid interval.(4) And after that, due to the continued expansion of the hematoma, this results in a rapid deterioration of neurological status. The source of bleeding mainly arterial injury of Middle Meningeal artery and could be venous or from bone sources. The mass effect of the hematoma causes an increased cranial pressure, and according to the Monro-Kellie principle; that states that the sum of blood, CSF, and brain volumes in the cranium are constant, (17) this eventually leads to a transtentorial uncal herniation. A series of clinical features develop in response to these events, including ipsilateral pupillary dilation (anisocoria) caused by parasympathetic oculomotor nerve compression, contralateral hemiparesis because of compression of the cerebral peduncle, and the compression to the brain stem causes Cushing triad (elevation in Blood pressure , Bradycardia and Irregular Breathing), and might lead to coma and death if not relieved as soon as possible. Other signs of increased ICP could present like headache, nausea, and vomiting. Early seizures presented in 8% of pediatric patients (18), and 27% of patients were neurologically intact. (8)

The presentation of all these symptoms depends on how rapidly the epidural hematoma is growing within the cranial vault, and the smaller the EDH is, the more likely it’ll be asymptomatic, it is a rare occasion though.

Also, epidural hematomas may present in a delayed fashion; up to 10% of patients who have sustained a head trauma, were found to have a normal head CT in the initial hours after the event, only for their neurological function to deteriorate rapidly and in a sudden manner, hours later. (19) Delayed epidural hematomas are more associated with a venous injury, rather than an arterial one.(1)

Work up and Diagnosis:

Traumatic brain injury cases should be managed thoroughly, starting with following the general trauma protocols. Immediate commencement of neuroprotective measures takes priority over diagnostics, to prevent or minimize secondary brain injuries. Therefore, maintenance of normal O2 saturation, normocapnia, normotension, and euglycemia is essential as a first step of primary survey.

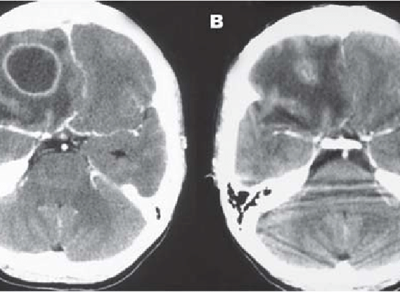

When an epidural hematoma is suspected based on the clinical features , an immediate head CT without IV contrast should be considered as a first line diagnostic procedure.(20) A head CT scan is the golden standard diagnostic model in showing the location of the hematoma, its amount, effect, and the other possible head injuries. An EDH forms a biconvex hyper-dense lesion with smooth margins on a CT scan, it could be accompanied with mass effect signs such as a midline shift (Figure 1). Although some recent studies showed that there is a possibility of the hematoma crossing suture lines in very rare cases,(21) it mostly does not due to the tight attachment of the dura mater to the skull at the sutures. Focal hypodense areas or presence of “swirl sign” within the EDH indicate active hyperacute bleeding in the majority of patients (Figure 2).

Figure (1) A. Axial non-contrast CT. B. Coronal non-contrast CT.

Large right convexity lentiform collection with several mass effect on the right cerebral hemisphere, leftward midline shift with a right temporal bone fracture. Case courtesy of Dr Michael P Hartung. (30)

Figure (2) Axial non-contrast CT.

Heterogeneous appearance of a swirl sign, suggestive of active bleeding.

Case courtesy of Dr Henry Knipe. (31)

A repeat of head CT scan is highly recommended for trauma patients who have suffered significant head injuries, and have either failed to improve, have had a secondary neurological deterioration, or have had an inexplainable increase in intracranial pressure, as a delayed epidural hematoma should be suspected (22) (23). Repetition of the CT scan allows for a more comprehensive observation of the growth of the hematoma on subsequent scans.

Head MRI without contrast could be considered in patients with neurological decline that is not explained by CT findings. It could also be used when having a difficulty differentiating between an epidural and a subdural hematoma or empyema on a CT scan. Epidural hematomas on MRI have similar features to those on CT scan, they show focal hypo-intensity on T2 sequence. While MRI is the preferred imaging tool in cases of suspected spinal EDH, because of its higher resolution properties, when compared to a spinal CT. (1)

Furthermore, CT angiography should be considered if vascular malformations are suspected, (24) and venography if cerebral venous sinus thrombosis is suspected. (25)

Other laboratory studies, like coagulation panel, and liver function tests, should be done to check for underlying coagulopathies or bleeding tendencies.

Treatment and Management:

As aforementioned, it is extremely important to effectively diagnose an epidural hematoma and to set a management plan as soon as possible, seeing as the outcome of the patients after treatment depends largely on how fast they get it, amongst other factors. Management of EDH patients starts with the general ABC principle, maintenance of ICP, and then a rapid neurologic evaluation to decide the next steps of treatment. (26)

The primary modality of treatment of an EDH is surgical evacuation, as it is considered a surgical emergency. The procedures which usually performed are craniotomy or decompressive craniectomy, they are both effective, but craniectomy performed for Epidural hematoma with moderate to severe brain edema in which we evacuate the hematoma and remove the bone. There is also a conservative, non-surgical choice, and the decision to choose between a surgical and a non-surgical approach depends on patient’s neurologic evaluation and characteristics of their hematoma. An epidural hematoma could be managed conservatively if it is less than 30 cm3, less than 15 mm in thickness, with a midline shift of no more than 5 mm, and the patient’s Glasgow coma scale (GCS) is above 8 with no visible neurological deficits. The patient should undergo a series of CT scans and should be closely monitored, as the hematoma could expand. As for surgery indications, an acute epidural hematoma with a volume more than 30 cm3, regardless of the GCS, or an epidural hematoma in a patient whose GCS is less than 9 and has pupillary abnormalities, should be immediately evacuated. (8)

Risk factors and Prognosis:

Numerous studies showcased the different prognostic factors and their effect on patient outcome following treatment, they all mostly agreed that older age, time taken before treatment initiation, presence of lucid interval and pupillary abnormalities, GCS score on admission, CT findings including signs of active bleeding, and high postoperative ICP, are all related to poorer prognosis, while the exact location of the hematoma and the cause of the trauma had no influence whatsoever on the outcome of EDH patients. (27) Epidural hematomas have a generally better prognosis than other brain lesions following a head trauma. (28) It has a relatively high mortality rate that can reach up to 10% in centers with neurosurgical facilities. (29)

Prevention:

Since most cases of EDHs are traumatic in nature, prevention mainly consists of raising awareness about the importance of using seatbelts and car seats, and wearing helmets for riding bikes, skateboards, and horses.