Abstract

The human CMP-N-acetylneuraminic acid hydroxylase gene (CMAH) suffered deletion of an exon that encodes an active center for the enzyme ∼3.2 million years ago (MYA). We analyzed a 7.3-kb intronic region of 132 CMAH genes to explore the fixation process of this pseudogene and the demographic implication of its haplotype diversity. Fifty-six variable sites were sorted into 18 different haplotypes with significant linkage disequilibrium. Despite the rather low nucleotide diversity, the most recent common ancestor at CMAH dates to 2.9 MYA. This deep genealogy follows shortly after the original exon deletion, indicating that the deletion has fixed in the population, although whether this fixation was facilitated by natural selection remains to be resolved. Remarkable features are exceptionally long persistence of two lineages and the confinement of one lineage in Africa, implying that some African local populations were in relative isolation while others were directly involved in multiple African exoduses of the genus Homo. Importantly, haplotypes found in Eurasia suggest interbreeding between then-contemporaneous human species. Although population structure within Africa complicates the interpretation of phylogeographic information of haplotypes, the data support a single origin of modern humans, but not with complete replacement of archaic inhabitants by modern humans.

SIALIC acids are components of cell-surface glycans and play an important role in cell-cell communication as well as in pathogen-host interactions during infectious processes (Angata and Varki 2002). The two most common forms of sialic acids found on mammalian cells are N-acetylneuraminic acid (Neu5Ac) and N-glycolylneuraminic acid (Neu5Gc). Neu5Gc is derived from Neu5Ac at the nucleotide sugar level through an enzymatic process catalyzed by CMP-N-acetylneuraminic acid hydroxylase (CMAH). Interestingly, the level of Neu5Gc is extremely low in the brain even in species with large amounts of Neu5Gc being expressed in other tissues (Kawano et al. 1995). The suppression of Neu5Gc is most conspicuous in humans in that there is no detectable level of Neu5Gc in almost all tissues (Muchmore et al. 1998). This was explained by the finding that the human CMAH locus is genetically inactivated despite the fact that it is a single-copy gene located on 6p21 (Chou et al. 1998; Irie et al. 1998), and it has been suggested that this defective mutation might be responsible for some biochemical or physiological characteristics specific to humans (Varki 2002).

The human CMAH gene is inactivated by deletion of the 92-bp exon (exon 6) that encodes an active center for the enzyme (Chou et al. 1998; Irie et al. 1998; Varki 2002). Hayakawa et al. (2001) studied the genomic sequences around exon 6 of various primate species and found that whereas the exon and a nearby AluSq element are present in all nonhuman primates, they are completely replaced by a young AluY element in humans. On the basis of the finding of a potential target-priming sequence by the Alu poly(A) tail located in the 5′ region immediately adjacent to the upstream deletion boundary, an Alu-mediated replacement of a genomic region was proposed as the underlying molecular mechanism (Hayakawa et al. 2001). Subsequently, Chou et al. (2002) took multiple approaches to estimate the timing of this Alu-mediated replacement. A method that extracts and identifies sialic acids from bones and bony fossils was developed and applied to samples, including two Neanderthal fossils. The absence of Neu5Gc in Neanderthal fossils strongly suggested that the inactivation of the human CMAH gene took place prior to the divergence of Neanderthals, ∼0.5 million years ago (MYA). Moreover, two other approaches using phylogeny of human-specific Alu's and molecular clocks consistently dated the much earlier occurrence of the inactivation that predated the first emergence of the genus Homo and of brain expansion in hominids (Chou et al. 2002).

CMAH is one of several human-specific functionless genes that have been caused by disruption or deletion of the coding frame and such loss of function might play some roles in evolution of human characteristics (Varki 2004). These human-specific functionless genes include those for T-cell receptor gamma chain V10 (Zhang et al. 1996), some olfactory receptors (Sharon et al. 1999; Gilad et al. 2003), type I hair keratin (Winter et al. 2001), myosin heavy chain (Stedman et al. 2004), SIGLEC13 (Angata et al. 2004), and bitter taste receptors (Conte et al. 2003; Go et al. 2005). Unlike CMAH, however, the others are generally members of multi-gene families with potential functional compensation by other paralogs. Recently, a systematic approach toward identifying human-specific gene death in the genome was developed. Since this approach needed to be very conservative, it could discover only four additional human-specific pseudogenes: vascular noninflammatory vanin, G-coupled receptor 33, double C2 gamma, and glycine receptor subunit (International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium 2004). In any event, it is important to ask when and how such human-specific loss of function appeared and spread over the world in relation to physiological or biochemical influences as well as human demographic history. It also needs to be examined whether such loss of function is actually fixed in the human population.

In this article, we focus on an ∼7.3-kb CMAH intronic region that encompasses the deleted exon 6. Using a sample of 132 chromosomes from 18 populations worldwide, we determined the linkage phase of the nucleotide sequences by allele-specific PCR (AS-PCR) or cloning and carried out the genealogical analysis of haplotypes under significant linkage disequilibium. We not only studied the fixation process of the CMAH pseudogene but also used its haplotype information to address human demographic history in the Plio–Pleistocene period.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA samples and intron sequences:

We purchased 66 human genomic DNAs from the Coriell Cell Repositories (CCR) and the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). These genomic DNAs come from 13 Africans and 53 non-Africans (Table 1). The chimpanzee and gorilla genomic DNAs are generous gifts of Colm O'hUigin (Max Planck Institut für Biologie, Tübingen, Germany; currently at the National Cancer Institute). We selected an intronic region ranging from position 9809 to 17,435 of the human CMAH pseudogene (GenBank accession no. AB009668). This region is 8100 and 8099 bp long for the gorilla and the chimpanzee, respectively, but it varies from 7611 to 7637 bp in the human. The region contains a human-specific AluY that replaced a genomic region, including functionally important exon 6 (Hayakawa et al. 2001). The AluY insertion is found in all human chromosomes examined, but not in the chimpanzee or in the gorilla. If we exclude the AluY and all other insertions or deletions (indels), the number of nucleotides that can be compared is 7302 bp long. The usage of purchased samples in this project was approved by a review board at CCR and ATCC.

TABLE 1.

Occurrences of 18 CMAH haplotypes in worldwide populations

| Africa

|

Europe

|

Asia

|

America

|

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haplotype | Af | Pb | Pm | Ad | Ru | Dr | Cu | Am | At | Ch | Jp | Cm | Ml | My | Kr | Su | Wr | Qu | Total |

| A0 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 80 | |

| A1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| A2 | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||

| A3 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| A4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | |||||||||||

| B0 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 10 | ||||||||||||||

| B1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| B2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 | |||||||||||||

| B3 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| B4 | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||

| B5 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| C0 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| C1 | 1 | 4 | 5 | ||||||||||||||||

| C2 | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||

| C3 | 3 | 3 | |||||||||||||||||

| C4 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| C5 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| P | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Total | 6 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 8 | 132 |

Af, African (ethnicity unknown); Pb, pygmy Biaka; Pm, pygmy Mbuti; Ad, Adygei; Ru, Russian; Dr, Druze; Cu, Caucasian (ethnicity unknown); Am, Ami; At, Atayal; Ch, Chinese; Jp, Japanese; Cm, Cambodian Khmer; Ml, Melanesian; My, Mayan; Kr, Karitiana; Su, Surui; Wr, Waorani; Qu, Quechua. Populations are categorized geographically into four groups: Africa: Af, Pb, and Pm; Europe: Ad, Ru, Dr, and Cu; Asia: Am, At, Ch, Jp, Cm, and Ml; and America: My, Kr, Su, Wr, and Qu.

Haplotype determination:

To unambiguously determine the linkage phase of all heterozygous sites, we employed both AS-PCR and cloning strategies. The AS-PCR strategy consisted of three procedures; detection of polymorphic sites, AS-PCR, and nested PCR (nPCR). The intronic region was amplified by primers CH-9 and CH-13, and the amplified PCR products were directly sequenced using an ABI Prism BigDye terminator cycle sequencing FS ready reaction kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Heterozygous sites were detected as double peaks indicated as “N” on an ABI Prism 377 fluorescent automated DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems). These heterozygous sites were then used to design 14 pairs of AS-PCR primers in combination with primers CH-9, CH-13, and CH-36. The AS-PCR was performed with 20 pmol of each primer and 100 ng of human genomic DNA in a total volume of 50 μl containing 200 μm dNTPs and 2.5 units of Ampli Taq Gold DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems) in PCR buffer containing 1.5 mm MgCl2. A RoboCycler gradient 96 (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) was used under the following conditions: denaturation at 95° for 15 min followed by 45 amplification cycles of 95° for 1 min, 62°–67° for 1 min, 69° for 5–7 min, and extension at 69° for 10 min. The AS-PCR products were purified through QIAquick PCR purification kits (QIAGEN, Chatsworth, CA) and used as templates for the nPCR that followed.

The nPCR was carried out to obtain a sufficient amount of appropriate AS-PCR products for sequencing. Primers CH-8, CH-40, and CH-59 were used instead of CH-9, CH-13, and CH-36. The PCR reaction was performed with 20 pmol of each primer and 1 μl of purified AS-PCR products in a total volume of 50 μl containing 200 μm dNTPs and 2.5 units of ExTaq DNA polymerase (Takara, Berkeley, CA) in a Takara ExTaq buffer containing 2 mm MgCl2. The PCR conditions were as follows: denaturation at 95° for 5 min followed by 30 cycles of 95° for 1 min, 60°–67° for 1 min, 69° for 7 min, and extension at 69° for 10 min. Products were directly sequenced in the same way as above. The haplotypes of five Africans including Biaka and Mbuti Pygmies were determined by this strategy.

The cloning strategy was performed as below. Genomic PCRs were performed with several primer sets (CH-9, CH-11, CH-13, CH-34, CH-36, CH-38, CH-43, CH-149, CH-157) according to the reported conditions (Hayakawa et al. 2001). Obtained genomic PCR products were purified as described above and were then cloned by using TOPO TA cloning kits (Invitrogen, San Diego). Finally, five to six clones from each of the cloned PCR products were sequenced.

For the chimpanzee genomic DNA, the AS-PCR strategy did not detect any heterozygous site so that the same PCR primers (CH-9, CH-10, CH-13, CH-34, CH-36, and CH-38) as those for the human were used. For the gorilla genomic DNA, the AS-PCR strategy was successful. In addition to the primers CH-8, CH-9, CH-36, and CH-40, new primers GoV-1A, GoV-1G, GoV-2C, and GoV-2G were used in both AS-PCR and nPCR to determine one haplotype. Temperatures of 58° and 62° were adopted for the PCR annealing step. Sequencing of these PCR products was carried out as for the human. The primer sequences of AS-PCR and genomic PCR are given in supplemental Table 1 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/.

Haplotype analyses:

DNASIS software (Hitachi, Tokyo) was used to assemble the sequences. The haplotype tree was constructed with the Gene Tree program (Griffiths and Tavaré 1994; Griffiths 2002). The HKA test by Hudson, Kreitman, and Aguadé (Hudson et al. 1987) and the relative rate test were performed using the DnaSP (version 4.0; Rozas et al. 2003) and MEGA3.1 software (Kumar et al. 2004), respectively. Some other statistical tests were performed on Mathematica.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Nucleotide diversity and linkage disequilibrium:

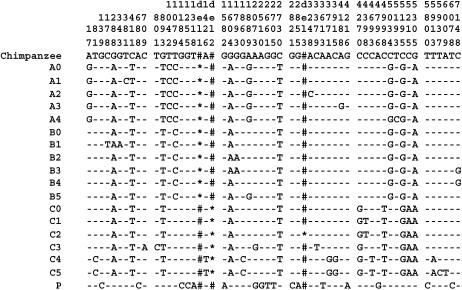

The sample of 132 sequences was divided into 18 haplotypes on the basis of 56 variable sites observed in the 7302-bp intronic region; 53 segregating sites and three indel sites (Table 1 and Figure 1). The average number of pairwise nucleotide differences is 3.8, which amounts to nucleotide diversity π = 0.052%. This is about half the commonly accepted value (Li and Sadler 1991, but see also Przeworski et al. 2000; International SNP Map Working Group 2001) and results from a low level of sequence differences (0.020%) in the non-African sample relative to 0.127% in the African sample. In the non-African sample with predominance of haplotype A0 (Table 1), there are a number of identical pairs of haplotypes and the mismatch distribution (pairwise nucleotide differences) is confined in a narrow range (Figure 2). The significantly negative D-value (D = −1.84, P < 0.05; Tajima 1989) or the significant excess in the number of segregating sites relative to π is consistent with a large proportion (5 of 9 haplotypes) of locality-specific young haplotypes in the non-African sample (Table 1 and Figure 1). One possibility for these features is the recent expansion of non-African populations (Excoffier 2002). On the other hand, in the African sample, there are only 25 identical pairs among 325 comparisons, the mismatch distribution is ragged in a large range (Figure 2), and the negative D-value of −1.06 is insignificantly different from 0 (P > 0.10). There is no evidence for population expansion within Africa (Excoffier 2002). We also found significantly high homozygosity (P < 0.05, χd.f.=12 = 4.70) in the total population, but no such excess (χd.f.=12 = 1.98) in the non-African sample. This suggests nonrandom mating within Africa as well as in the entire population (see below).

Figure 1.

Fifty-six variable sites in 18 human CMAH haplotypes. The nucleotide sequence position 1 corresponds to 9809 in AB009668. A dash indicates a nucleotide that is identical to that in the top line sequence of the chimpanzee. Del 1, 2, and 3 are indels at positions for 1356–1374, 1435–1438, and 3228–3234, respectively. “#” and “*” indicate the presence and absence of sequences, respectively.

Figure 2.

The mismatch distribution of nucleotide differences within Africans (solid circles and scale on the left) and within non-Africans (open circles and scale on the right). The x- and y-axes represent the number of nucleotide differences between a pair of haplotypes and a proportion of the number of haplotype pairs with nucleotide differences, respectively.

Among the 53 segregating sites, 34 are singletons and 19 are phylogenetically informative. Of these, there are two phylogenetically incompatible sites (position 1793 or 7148 and position 2073 in Figure 1), which stem from parallel nucleotide substitutions, as we explain below. As for the indel sites, two are informative and compatible with each other and to most of the segregating sites. To quantify the tight linkage among the 21 informative sites, we applied the four-gamete test (Hudson 1987; Takahata and Satta 1998). Of a total of 210 pairwise comparisons, only 9 pairs of sites are incompatible with each other, the proportion (9/210) being much lower than the 25/528 observed at the nearby hemochromatosis (HFE) locus (Toomajian and Kreitman 2002). Consistent with this, many pairs of informative sites at CMAH are under significant linkage disequilibrium (Weir 1990) and the proportion (81/210) of those pairs is much higher than that (86/528) at HFE. If the recombination rate at HFE is close to the genomic average (Przeworski et al. 2000; Frisse et al. 2001; Toomajian and Kreitman 2002), CMAH must have undergone a lowered level of recombination. Since these observations indicate that CMAH samples are almost free from recombination, we used the entire region and all the haplotypes in the following phylogeographic analysis.

Fixation and time frame of CMAH genealogy:

To define the time frame in the CMAH haplotype genealogy, we also determined the chimpanzee and gorilla orthologous sequences. The mean nucleotide divergence between the human and the chimpanzee is 0.82 ± 0.11%. Although the value is slightly smaller than that of other autosomal loci (Satta and Takahata 2004), an even smaller value (0.69%) is observed at HFE (Toomajian and Kreitman 2002). Actually, however, these small values are close to the mode (0.75%) of nucleotide divergences in >30,000 comparisons of human and chimpanzee BAC end sequences (Fujiyama et al. 2002). If the human and the chimpanzee diverged 6 MYA (Haile-Selassie 2001; Burnet et al. 2002; Haile-Selassie et al. 2004), the nucleotide substitution rate (μ) at CMAH can be estimated as 0.68 ± 0.09 × 10−9/site/year. However, this relatively low μ-value does not result from a demographic cause such as recent introgression from the chimpanzee to the human or vice versa. Rather, it reflects the intrinsic mutation rate, because almost the same rate (0.71 ± 0.08 × 10−9/site/year) is obtained from the sequence divergence between the human and the gorilla (1.10 ± 0.12%) assuming that they diverged from each other 7.7 MYA (Horai et al. 1992; Kumar and Hedges 1998). The relative rate test with the gorilla sequence as an outgroup also shows no significant rate heterogeneity between the human and chimpanzee lineages (data not shown).

The CMAH haplotypes exhibit two distinct lineages: the P lineage, which has left a single descendant haplotype P that is represented by two heterozygous individuals in the sub-Saharan Biaka pygmy population, and the non-P lineage, which has been extensively diversified to produce A, B, and C sublineages (Figure 3). Haplotype P is most distantly related and connected to the non-P haplotypes through the most common recent ancestor (MRCA). The average sequence divergence between the two lineages is 0.40 ± 0.07% and is nearly half of that between the human and the chimpanzee. With μ = 0.68 × 10−9, the time back to the MRCA (TMRCA) can be estimated as 2.9 ± 0.5 million years (MY). This value is in contrast to rather shallow genealogies of most loci studied thus far in the human population (Takahata et al. 2001; Satta and Takahata 2002, 2004; Templeton 2002). An exception is the eosinophil-derived neurotoxin locus (Zhang and Rosenberg 2000) at which the TMRCA is estimated as 3 MY (Satta and Takahata 2004) or even greater (Templeton 2002), although the dating is subject to a large sampling error owing to a small number of segregating sites in the region examined. One may wonder if such an ancient MRCA results from the hitchhiking effect of neighboring polymorphic loci under balancing selection. Indeed, CMAH is located in a telomeric region 5 Mb apart from the highly polymorphic human leucocyte antigen (HLA) complex on chromosome 6. However, HFE is located 1 Mb closer to HLA than CMAH, but the former locus does not show any evidence for the hitchhiking effect (Toomajian and Kreitman 2002). This observation argues strongly against the likelihood of the hitchhiking effect at even distantly located CMAH. We also examined if the number of polymorphic sites is consistent with the number of nucleotide differences between species, as expected under neutrality (Hudson et al. 1987). Despite the long-lasting P lineage in the African population, CMAH does not show any significant deviation from other loci (Table 2). Thus, CMAH provides compelling evidence for a presumably neutral locus with TMRCA > 2 MY and suggests that MRCAs at some nuclear loci, even though evolving in a neutral fashion, can be found during the era of Australopithecines. In other words, CMAH provides another example of the African origin of human genetic variation and increases the proportion of the African MRCA (Satta and Takahata 2004) up to 93% among the total of 15 nuclear loci studied thus far.

Figure 3.

Gene tree of 18 human CMAH haplotypes when the chimpanzee sequence was used to infer the MRCA sequence. A dot and a tick mark represent a nucleotide substitution and an indel, respectively. Parallel substitutions at 2073 are placed on the branches leading to P and C3. Similarly, parallel substitutions at 1793 are placed on the B2 and B3 terminal branches. The arrow in the tree denotes the exon deletion by AluY insertion.

TABLE 2.

HKA tests for neutrality between CMAH and other loci

| Lengtha

|

Sample sizeb

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locus | Location | L1 | L2 | n1 | n2 | Dc | Kd | χ2 | P |

| α-Globin | 16p13.3 | 310 | 310 | 553 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 0.002 | 0.966 |

| β-Globin | 11p15.5 | 2320 | 2320 | 326 | 1 | 18 | 35 | 2.083 | 0.149 |

| ECP | 14q24–q31 | 1203 | 1203 | 108 | 1 | 7 | 16 | 1.194 | 0.275 |

| EDN | 14q24–q31 | 1214 | 1214 | 134 | 1 | 9 | 9 | 0.039 | 0.844 |

| HFE | 6p21.3 | 11214 | 11214 | 60 | 1 | 41 | 77 | 0.549 | 0.459 |

| Mc1r | 16q24.3 | 955 | 954 | 242 | 1 | 6 | 17 | 2.853 | 0.091 |

| PDHA1 | Xp22.11 | 4149 | 4149 | 34 | 2 | 23 | 42 | 0.011 | 0.915 |

| Xq13.3 | Xq13.3 | 10163 | 10163 | 69 | 1 | 33 | 94 | 1.380 | 0.240 |

| ZFX | Xp21.3 | 1215 | 1173 | 335 | 1 | 10 | 17 | 0.422 | 0.516 |

| CMAH | 6p21.32 | 7302 | 7302 | 132 | 1 | 53 | 60 | — | — |

L1 is the length compared within humans and L2 is that between humans and chimpanzees.

n1 is the sample size from humans and n2 is that from chimpanzees.

The number of polymorphic sites in humans.

The mean number of nucleotide differences between humans and chimpanzees.

Our original estimate of CMAH inactivation was 2.8 MYA (Chou et al. 2002). This was based on the assumption of the 5.3-MY divergence time between the human and the chimpanzee. Recent findings of more ancient hominid fossils pushed the assumed divergence time back to 6–7 MY (Haile-Selassie 2001; Burnet et al. 2002; Haile-Selassie et al. 2004). If we assume a 6-MY divergence time, our estimate of CMAH inactivation time (T) becomes 3.2 MY and that of TMRCA in the sample becomes 2.9 MY, suggesting that the deletion mutation fixed in the human population long ago. Of particular interest is that TMRCA is fairly close to T: There is a mere 0.3-MY difference between T and TMRCA (Figure 3). To explore what this relatively short duration time tells us about the evolutionary force in the fixation process of the CMAH pseudogene, it is necessary to have some idea about the effective size of the human population during the Plio–Pleistocene period. It is conceivable that since Australopithecines expanded widely over the African continent, there was fairly strong isolation among rather sessile local populations (Klein and Takahata 2002). The CMAH genealogy is consistent with such a view that Australopithecines were geographically structured and genetically differentiated and suggests that the transformation to the genus Homo occurred in some such local populations. Indeed, prior genetic data and theoretical consideration (Takahata 1995) suggested that the human population had its effective size (Ne) of the order of 105 before the emergence of the genus Homo ∼2 MYA. This large effective size may be partly due to limited amounts of gene flow among local populations (Nei and Takahata 1993; Takahata 1995). In any event, if the effective size was as large as 105 throughout the Pliocene period, it would have taken more than a few million years for the CMAH deletion mutation to become fixed in the population by random genetic drift alone (Kimura and Ohta 1969). If the mutation had long been segregated in the human population with low frequencies, it is possible that extensive allelic diversification within this particular mutation would have been retarded and that the TMRCA would have become much smaller than T, contrary to the current observation. Alternatively, since Neu5Gc is a target for some microorganisms to gain entry into mammalian cells (Angata and Varki 2002), it is possible that a virulent pathogen with such a binding affinity might have selected for an increased frequency of the CMAH deletion mutation in a certain ancestral Australopithecine population.

One can then ask to what extent the fixation process of the CMAH deletion mutation could affect its TMRCA among the descendants if it was somehow selectively advantageous and could rapidly increase its frequency. We examined the effect of selection by carrying out computer simulation and compared the distribution of TMRCA with and without genic selection. Following Takahata (1995), we also assumed a sudden reduction in Ne from 105 to 104 T1 = 2 MYA. Provided that the deletion mutation arose T = 3.2 MYA (1.6 × 105 generations for the generation time of 20 years) and has eventually fixed in the population, we recorded the neutral gene genealogy of the present-day descendants. To perform this time-consuming simulation forward in time, we assumed a small Ne, reducing from 100 to 10; a strong selection intensity of s = 0.5; and a high neutral mutation rate of μ = 0.1/gene/unit time. This unit time actually corresponds to 1000 generations so that the deletion mutation arose 160 units of time ago in the simulation. We then obtained the TMRCA in each simulation and the distribution over 1000 cases of the fixation. The probability that TMRCA > 2 MY (or 100 units of time) tended to be high with selection, but the excess was slight and as a whole the distribution itself was insensitive to selection (data not shown). This overall insensitivity results from the fact that the Pleistocene period is long enough to erase the footprint of an ancient action of natural selection on the genealogy, even if exerted. In fact, if we use smaller T and T1 values than the above, the effect of selection becomes visible and the TMRCA becomes long. For instance, if T = 1.6 MY and T1 = 1 MY, the mean and standard deviation of TMRCA become 4.50 ± 2.98 (× 104) with selection, whereas they become 3.56 ± 3.23 (× 104) without selection.

Haplotype distribution and human demography:

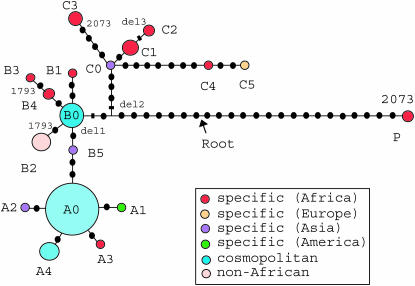

The non-P lineage is one of the two ancient lineages and produced A, B, and C sublineages. These sublineages contain all the remaining 17 haplotypes. Of these, 3 (A0, A4, B0) are cosmopolitan, 1 (B2) is specific to non-African, and 13 are restricted to one continent: 8 (A3, B1, B3, B4, C1, C2, C3, C4) to Africa, 3 (A2, B5, C0) to Asia, 1 (C5) to Europe, and 1 (A1) to America (Figure 4). The C sublineage is of rather ancient African origin and diverged from the ancestral lineage of A and B ∼1 MYA (Figure 3). Interestingly, each of all six C haplotypes (C0–C5) occurs in a single continent: C0 and C5 are found in Asian and European samples, respectively, whereas the remaining four are found only in African samples. However, since C5, found only in Russians, shares seven substitutions with African-specific C4 (Table 1 and Figure 1), it is most likely that the occurrence of C5 in Europe resulted from recent migration from Africa. As for the C0 haplotype, we note that it is ancestral to the C sublineage and represented by a single Asian chromosome in the sample. Because of the antiquity and rarity, it is likely that the C0 haplotype originally arose in Africa and then migrated into Asia.

Figure 4.

Haplotype network. Each colored circle represents a haplotype and the size is in proportion to the frequency. As in Figure 3, a dot and a tick represent a nucleotide substitution and an indel, respectively. Parallel substitutions in P and C3 and in B2 and B3 are indicated by position nos. 2073 and 1793, respectively.

On the other hand, all cosmopolitan haplotypes (A0, A4, and B0) belong to either the A or B sublineage (Figures 3 and 4). Despite the young age (∼0.1 MY), A0 is a major cosmopolitan haplotype and increases its frequency dramatically from Africa (11.5%) to Europe (46.4%) to Asia (79.5%) and then to America (85.3%), similar to the textbook example of the blood-type O antigen. The genealogical relationships among A sublineage haplotypes clearly suggest that A0 is ancestral to one minor cosmopolitan A4, one African A3, and two non-African-specific A1 and A2 (Table 1, Figures 3 and 4). If A0 emerged in Africa and expanded worldwide, it is likely that the African A3 is an early descendant and the other A sublineages are relatively young descendants of emigrating A0. These phylogeographic patterns can be most parsimoniously accounted for if an out-of-Africa migration of modern humans occurred before diversification of the A sublineage 0.1 MYA, but after the divergence of the A sublineage from the ancestral B5 haplotype ∼0.4 MYA (Figure 3). Such a migration is in agreement with the major expansion of modern humans that took place 0.08 to 0.15 MYA, as suggested by mitochondrial DNA (Cann et al. 1987; Ingman et al. 2000) and Y chromosomes (Thomson et al. 2000).

By contrast, the B sublineage provides information about more ancient human migration than the A sublineage. Cosmopolitan B0 is an immediate ancestor of B1, B2, B3, and B4. Notably, B2 is not found in Africa, but B1, B3, and B4 are confined to Africa (Figure 4). To discuss the genealogical relationships among these haplotypes, it is necessary to pay attention to the G/A polymorphism at position 1793 that is incompatible with the great majority of polymorphic sites and is shared by B2 and B3. One possibility for this incompatible polymorphism is that either B2 is a recombinant between B0 and B3 or B3 is a recombinant between B2 and B4. However, because of the rarity of B3 and B4, both of which are confined to Africa, this possibility is less likely than the alternative that the G → A transitions in B2 and B3 result from parallel nucleotide substitutions. Under this alternative, we assume that B0 arose in Africa and B2 arose somewhere in Eurasia. Since B0 can be traced back to ∼1 MYA and B2 descended ∼0.2 MYA (Figure 3), cosmopolitan B0 might have migrated out of Africa during the period from 0.2 to 1 MYA. In other words, migration of B0 took place earlier than that of A0, suggesting that both B0 and B2 in Eurasian populations of archaic humans were transmitted to modern humans by interbreeding (Lewin 1998; Templeton 2002). It was argued that northeastern African populations served as genetic reservoirs and migration therefrom was biased toward Eurasia (Tishkoff et al. 1996; Satta and Takahata 2004). It is then possible that B2 originally arose in northeastern Africa, but subsequently it was lost or became so rare as to be undetected in the present African sample. In either case, our data strongly suggest direct transmission of B2 from archaic to modern humans in northeastern Africa or in Eurasia. In conclusion, the expansion of the relatively young A0 haplotype has undoubtedly made a major impact on the CMAH diversity in the human population. However, the presence of relatively old B0 and its direct descendant B2 in Asia supports the hypothesis of a single African origin of modern humans, but not with complete replacement of archaic inhabitants.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mineyo Iwase for technical advice and Michael Kryshak for editorial assistance. This work was supported in part by the Japan Society for Promotion of Science grant 12304046 to N.T. and by grant GM32373 to A.V.

References

- Angata, T., and A. Varki, 2002. Chemical diversity in the sialic acids and related alpha-keto acids: an evolutionary perspective. Chem. Rev. 102: 439–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angata, T., E. H. Margulies, E. D. Green and A. Varki, 2004. Large-scale sequencing of the CD33-related Siglec gene cluster in five mammalian species reveals rapid evolution by multiple mechanisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101: 13251–13256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet, M., F. Guy, D. Pilbeam, H. T. Mackaye, A. Likius et al., 2002. A new hominid from the upper Miocene of Chad, central Africa. Nature 418: 145–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cann, R. L., M. Stoneking and A. C. Wilson, 1987. Mitochondrial DNA and human evolution. Nature 325: 31–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou, H.-H., H. Takematsu, S. Diaz, J. Iber, E. Nickerson et al., 1998. A mutation in human CMP-sialic acid hydroxylase occurred after the Homo-Pan divergence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95: 11751–11756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou, H.-H., T. Hayakawa, S. Diaz, M. Krings, E. Indriati et al., 2002. Inactivation of CMP-N-acetylneuraminic acid hydroxylase occurred prior to brain expansion during human evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99: 11736–11741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conte, C., M. Ebeling, A. Marcuz, P. Nef and P. J. Andres-Barquin, 2003. Evolutionary relationships of the Tas2r receptor gene families in mouse and human. Physiol. Genomics 14: 73–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Excoffier, L., 2002. Human demographic history: refining the recent African origin model. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 12: 675–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisse, L., R. R. Hudson, A. Bartoszewicz, J. D. Wall, J. Donfack et al., 2001. Gene conversion and different population histories may explain the contrast between polymorphism and linkage disequilibrium levels. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 69: 831–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiyama, A., H. Watanabe, A. Toyoda, T. D. Taylor, T. Itoh et al., 2002. Construction and analysis of a human-chimpanzee comparative clone map. Science 295: 131–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilad, Y., O. Man, S. Pääbo and D. Lancet, 2003. Human specific loss of olfactory receptor genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100: 3324–3327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go, Y., Y. Satta, O. Takenaka and N. Takahata, 2005. Lineage-specific loss of function of bitter taste receptor genes in humans and non-human primates. Genetics 170: 313–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, R. C., 2002. Ancestral inference from gene trees, pp. 94–117 in Modern Developments in Theoretical Population Genetics, edited by M. Slatkin and M. Veuille. Oxford University Press, New York.

- Griffiths, R. C., and S. Tavaré, 1994. Simulating probability distribution in the coalescent. Theor. Popul. Biol. 46: 131–159. [Google Scholar]

- Haile-Selassie, Y., 2001. Late Miocene hominids from the middle Awash, Ethiopia. Nature 412: 178–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haile-Selassie, Y., G. Suwa and T. D. White, 2004. Late Miocene teeth from middle Awash, Ethiopia, and early hominid dental evolution. Science 303: 1503–1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa, T., Y. Satta, P. Gagneux, A. Varki and N. Takahata, 2001. Alu-mediated inactivation of the human CMP-N-acetylneuraminic acid hydroxylase gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98: 11399–11404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horai, S., Y. Satta, K. Hayasaka, R. Kondo, T. Inoue et al., 1992. Man's place in hominoidea revealed by mitochondrial DNA genealogy. J. Mol. Evol. 35: 32–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, R. R., 1987. Estimating the recombination parameter of a finite population model without selection. Genet. Res. 50: 245–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, R. R., M. Kreitman and M. Aguadé, 1987. A test of neutral molecular evolution based on nucleotide data. Genetics 116: 153–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingman, M., H. Kaessmann, S. Pääbo and U. Gyllensten, 2000. Mitochondrial genome variation and the origin of modern humans. Nature 408: 708–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium, 2004. Finishing the euchromatic sequence of the human genome. Nature 431: 931–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International SNP Map Working Group, 2001. A map of human genome sequence variation containing 1.42 million single nucleotide polymorphisms. Nature 409: 928–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irie, A., S. Koyama, Y. Kozutsumi, T. Kawasaki and A. Suzuki, 1998. The molecular basis for the absence of N-glycolylneuraminic acid in humans. J. Biol. Chem. 273: 15866–15871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano, T., S. Koyama, H. Takematsu, Y. Kozutsumi, H. Kawasaki et al., 1995. Molecular cloning of cytidine monophospho-N-acetylneuraminic acid hydroxylase. Regulation of species- and tissue-specific expression of N-glycolylneuraminic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 270: 16458–16463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, M., and T. Ohta, 1969. The average number of generations until fixation of mutant genes in a finite population. Genetics 61: 763–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein, J., and N. Takahata, 2002. Where Do We Come From? The Molecular Evidence for Human Descent. Springer-Verlag, Berlin.

- Kumar, S., and S. B. Hedges, 1998. A molecular timescale for vertebrate evolution. Nature 392: 917–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S., K. Tamura and M. Nei, 2004. MEGA 3: integrated software for molecular evolutionary genetics analysis and sequence alignment. Brief. Bioinformatics 5: 150–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin, R., 1998. Principles of Human Evolution. Blackwell Scientific, Oxford.

- Li, W.-H., and L. A. Sadler, 1991. Low nucleotide diversity in man. Genetics 129: 513–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muchmore, E. A., S. Diaz and A. Varki, 1998. A structural difference between the cell surfaces of humans and the great apes. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 107: 187–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nei, M., and N. Takahata, 1993. Effective population size, genetic diversity, and coalescence time in subdivided populations. J. Mol. Evol. 37: 240–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przeworski, M., R. R. Hudson and A. Di Rienzo, 2000. Adjusting the focus on human variation. Trends Genet. 16: 296–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozas, J., J. C. Sánchez-DelBarrio, X. Messegyer and R. Rozas, 2003. DnaSP, DNA polymorphism analyses by the coalescent and other methods. Bioinformatics 19: 2496–2497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satta, Y., and N. Takahata, 2002. Out of Africa with regional interbreeding? Modern human origins. BioEssays 24: 871–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satta, Y., and N. Takahata, 2004. The distribution of the ancestral haplotype in finite stepping-stone models with population expansion. Mol. Ecol. 13: 877–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharon, D., G. Glusma, Y. Pilpel, M. Khen, F. Gruetzner et al., 1999. Primate evolution of an olfactory receptor cluster: diversification by gene conservation and recent emergence of pseudogenes. Genomics 61: 24–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stedman, H. H., B. W. Kozyak, A. Nelson, D. M. Thesier, L. T. Su et al., 2004. Myosin gene mutation correlates with anatomical changes in the human lineage. Nature 428: 415–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima, F., 1989. Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics 123: 585–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahata, N., 1995. A genetic perspective on the origin and history of humans. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 26: 343–372. [Google Scholar]

- Takahata, N., and Y. Satta, 1998. Footprints of intragenic recombination at HLA loci. Immunogenetics 47: 430–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahata, N., S.-H. Lee and Y. Satta, 2001. Testing multiregionality of modern human origins. Mol. Biol. Evol. 18: 172–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Templeton, A., 2002. Out of Africa again and again. Nature 416: 45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, R., J. K. Pritchard, P. Shen, P. J. Oefner and M. W. Feldman, 2000. Recent common ancestry of human Y chromosomes: evidence from DNA sequence data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97: 7360–7365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tishkoff, S. A., E. Dietzsch, W. Speed, A. J. Pakstis, J. R. Kidd et al., 1996. Global patterns of linkage disequilibrium at the CD4 locus and modern human origins. Science 271: 1380–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomajian, C., and M. Kreitman, 2002. Sequence variation and haplotype structure at the human HFE locus. Genetics 161: 1609–1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varki, A., 2002. Loss of N-glycolylneuraminic acid in humans: mechanisms, consequences and implications for hominid evolution. Yearb. Phys. Anthropol. 44: 54–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varki, A., 2004. How to make an ape brain. Nat. Genet. 36: 1034–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir, B. S., 1990. Genetic Data Analysis. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA.

- Winter, H., L. Langbein, M. Krawczak, D. N. Cooper, L. F. Jave-Suarez et al., 2001. Human type I hair keratin pseudogene ψhHaA has functional orthologs in the chimpanzee and gorilla: evidence for recent inactivation of the human gene after the Pan-Homo divergence. Hum. Genet. 108: 37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J., and H. F. Rosenberg, 2000. Sequence variation at two eosinophil-associated ribonuclease loci in humans. Genetics 156: 1949–1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X. M., G. Cathala, Z. Soua, M. P. Lefranc and S. Huch, 1996. The human T-cell receptor gamma variable pseudogene V10 is a distinctive marker of human speciation. Immunogenetics 43: 196–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]