Abstract

Motivation: Random effects models have recently been introduced as an approach for analyzing genome wide association studies (GWASs), which allows estimation of overall heritability of traits without explicitly identifying the genetic loci responsible. Using this approach, Yang et al. (2010) have demonstrated that the heritability of height is much higher than the ~10% associated with identified genetic factors. However, Yang et al. (2010) relied on a heuristic for performing estimation in this model.

Results: We adopt the model framework of Yang et al. (2010) and develop a method for maximum-likelihood (ML) estimation in this framework. Our method is based on Monte-Carlo expectation-maximization (MCEM; Wei et al., 1990), an expectation-maximization algorithm wherein a Markov chain Monte Carlo approach is used in the E-step. We demonstrate that this method leads to more stable and accurate heritability estimation compared to the approach of Yang et al. (2010), and it also allows us to find ML estimates of the portion of markers which are causal, indicating whether the heritability stems from a small number of powerful genetic factors or a large number of less powerful ones.

Contact: saharon@post.tau.ac.il

1 INTRODUCTION

Many complex traits display a remarkable gap between the overall genetic variance estimated by population studies (such as twin studies) and the variance explained by specific genetic variants identified by genome wide association studies (GWASs). This gap has been coined the ‘dark matter’ of heritability (Manolio et al., 2008). Suggested explanations for this gap include gene–gene and gene-environment interactions (Manolio et al., 2008; Visscher et al., 2008), unidentified by the univariate GWAS scheme, though some of these explanations have been refuted by studies (Hill et al., 2008).

Height, being a trait that is easy to measure but genetically complex, has attracted special attention. Heritability of height, defined as the portion of height variability due to genetic factors, was estimated at around 80% (Macgregor et al., 2006; Visscher, 2008; Visscher et al., 2008) while the tens of specific single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) identified by large-scale GWASs account for only 10% of the heritability (Gudbjartsson et al., 2008; Lettre et al., 2008; Weedon et al., 2008). Extrapolating from these data, under specific statistical assumptions, Goldstein (2009) estimated the number of causal SNPs affecting height at 93 000, which is at the high end of reasonable values.

(Yang et al., 2010) recently suggested the use of random effects models as a multivariate approach for estimating the heritability of height directly from GWAS data. In their model, each individual's height is affected by a genetic random effect, which is correlated across individuals by virtue of sharing some of the genetic variants affecting height, and an environmental random effect, which is uncorrelated across individuals. Consistent with the common definition, they define heritability as the ratio of the variance of the genetic random effect to the total variance.

Using a straightforward maximum-likelihood approach for estimating heritability in this model requires knowledge of the identity of the causal SNPs, and hence the covariance matrix. This is of course not available, so Yang et al. (2010) approximate the genetic correlation between every pair of individuals across the set of causal SNPs by the genetic correlation across the set of all genotyped SNPs. Using this approximation they estimate the heritability of height at 45%. By adding some further assumptions about the nature and distribution of the causative SNPs they obtain heritability estimates of 56% and 80%.

While the random effects approach proposed by Yang et al. (2010) is innovative and appropriate, the concept of using an estimated correlation matrix instead of the actual correlation matrix is a questionable heuristic. The very large number of SNPs used for estimating the genetic correlations—most of them likely not causative—might mask out the correlations on the set of causal SNPs. As we show below, this indeed leads to inaccurate and suboptimal estimation of heritability.

Instead, we propose here to treat the identity of the causal SNPs as missing data, and find true maximum-likelihood estimates of our parameters of interest in this setting. Towards this end, we develop an expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm for this problem. Because of the exponentially large data space, we employ Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods for the estimation of the E-step. This approach is known as Markov-chain expectation-maximization (MCEM; Wei et al., 1990). We also develop an efficient optimization approach for the M-step, based on spectral decomposition of the estimated covariance matrix.

The resulting algorithm is computationally intensive, yet tractable for reasonably sized problems, as we demonstrate. As a by-product of our approach, we also get maximum-likelihood estimates of the portion of genotyped SNPs that are causative in the random effect model. This represents independently useful information, as it indicates whether the estimated heritability is likely due to a small number of large genetic effects, or a large number of smaller effects. For example, this knowledge may be useful in planning further studies to identify these specific factors.

We empirically demonstrate using simulations that our method, in addition to being theoretically sound, does indeed lead to significantly more accurate estimation of heritability than the heuristic approach of Yang et al. (2010).

2 METHODS AND SIMULATIONS

2.1 Random effect models of genetic causality

We first describe the random effects model proposed by Yang et al. (2010). Assume we have n individuals with their quantitative phenotype (say, height) denoted by yj , j=1…n, and we know there are m genetic factors affecting the phenotype, as described by the following model:

where zij is the value of the i-th causative SNP of the j-th individual after standardization, i.e.  where xij is the actual genotype and pi is the minor allele frequency (MAF), so E(zij)=0 and V(zij)=1. ui~N(0,σu2) is the effect of the i-th SNP on height. ej~N(0,σe2) is the environmental effect which is assumed to be i.i.d. across individuals. μ is the mean term, that is typically assumed to be known and equal to 0 (i.e. it has been subtracted), and m is the number of causal SNPs.

where xij is the actual genotype and pi is the minor allele frequency (MAF), so E(zij)=0 and V(zij)=1. ui~N(0,σu2) is the effect of the i-th SNP on height. ej~N(0,σe2) is the environmental effect which is assumed to be i.i.d. across individuals. μ is the mean term, that is typically assumed to be known and equal to 0 (i.e. it has been subtracted), and m is the number of causal SNPs.

Defining gj=∑i=1mzijui as the genetic random effect of individual j, the genetic variance is given by var(gj)=σg2=mσu2, and

From here it follows that y~N(0,Gσg2+Iσe2) where  and Z is the genotypes matrix. G can be interpreted as the genetic correlation matrix. Heritability, or the share of the genetic variance in the overall variance, is given by

and Z is the genotypes matrix. G can be interpreted as the genetic correlation matrix. Heritability, or the share of the genetic variance in the overall variance, is given by  . All that is needed for maximum-likelihood estimation of h2 using standard random effects regression approaches (Searle et al., 1992) is the genetic correlation matrix G and the phenotypes vector y.

. All that is needed for maximum-likelihood estimation of h2 using standard random effects regression approaches (Searle et al., 1992) is the genetic correlation matrix G and the phenotypes vector y.

2.2 Estimation approach of Yang et al. (2010)

Yang et al. (2010) acknowledge the fact that the identity of the causal SNPs is unknown, and therefore G cannot be directly obtained. Assume that we have performed genome-wide genotyping on the n individuals, with a total of N genotyped SNPs on each. Yang et al. (2010)) propose to use the overall genetic correlations matrix  computed on the entire genotyped data W (instead of just the ‘causative’ matrix Z) as an estimate of G. Yang et al. (2010) further improve this estimate in two ways.

computed on the entire genotyped data W (instead of just the ‘causative’ matrix Z) as an estimate of G. Yang et al. (2010) further improve this estimate in two ways.

First, Yang et al. (2010) correct the sampling bias along the diagonal of the matrix by defining A not as the cross-product of the genotype matrix, but by defining instead:

Second, Yang et al. (2010) account for linkage disequilibrium (LD) between genotyped SNPs and causal SNPs by replacing A with A*=β(A−I)+I where β is a parameter which is estimated from the genotyped data, using simulations which are based on assumptions as to the number of causal SNPs and their MAF. This can be thought of as regressing G on A and replacing A with the conditional expectation of G given A.

After obtaining the A* matrix, Yang et al. (2010) use restricted maximum likelihood (REML) for obtaining estimates of the variance components and hence heritability in the model y~N(0,A*σg2+Iσe2) instead of the real model y~N(0,Gσg2+Iσe2) for which the variance–covariance matrix is unknown. As we discuss later, this heuristic is statistically unbased and introduces substantial error to the estimation. We thus seek a more rigorous estimation approach.

2.3 Missing data representation of the problem

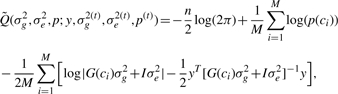

We wish to treat the identity of the causal SNPs as missing data, and therefore assume each SNP is causal with probability p. It is convenient to think about the set of causal SNPs as a bit mask represented by the number c with that bit mask as a binary representation. So 0 represents no causal SNPs while 2N−1 means all SNPs are causal (where N is the number of genotyped SNPs), and the probability of observing a causal SNPs set c is p(c)=p#c(1−p)N−#c where #c is the number of causal SNPs in c. We denote by G(c) the genetic correlation matrix based on the causal SNPs in c. Given c, the log of the full likelihood can now be written as:

|

Since we do not know c we use EM (Dempster et al., 1977) to find maximum-likelihood estimates of our parameters of interest.

2.4 E-Step

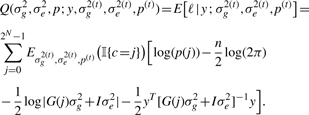

The E-step takes the form:

|

From Bayes' theorem it follows that for all j:

|

where ϕ(y;Σ) is the multivariate normal density of the observed vector y given the variance-covariance matrix Σ.

2.5 MCMC estimation of the E-step

Clearly, it is not feasible to sum over 2N summands for even modest values of N. We therefore use a MCMC scheme to estimate the conditional expectation of the log-likelihood. Given M samples from the conditional distribution of c: P(c|y;σg2(t),σe2(t),p(t)) labeled c1,…,cM we estimate the E-step with the empirical mean  :

:

|

To sample the conditional distribution of c, we specify the Metropolis algorithm in a manner similar to McCulloch, (1990). We specify the candidate distribution hc(c) from which potential values are drawn and the acceptance function that gives the probability of accepting the new value.

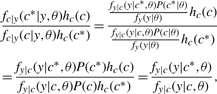

Let c be the last draw from the conditional distribution of c with (b1,b2,…,bN) being its binary representation. We generate a new value bk* for the k-th component of c using the candidate distribution hc. We accept c*=(b1,…,bk*,…,bN) as the new value with the probability Ak(c,c*) given by:

Taking hc(c)=p#c(1−p)1−#c the second term takes a particularly convenient form:

|

which is simply the ratio of the likelihoods.

2.6 M-step

Rewriting the empirical mean  resulting from the MCMC:

resulting from the MCMC:

|

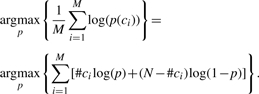

indicates that the optimization in the M-step is done separately for p and for the variance components. For p we wish to solve:

|

Differentiating w.r.t p yields:

which is simply the average of causal SNPs proportions in the samples.

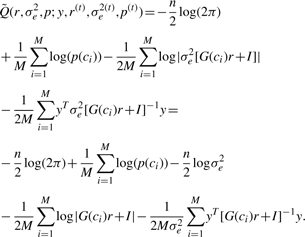

For the variance components, it is beneficial to rewrite the equation as a function of (r,σe2) with  instead of (σg2,σe2). We then get:

instead of (σg2,σe2). We then get:

|

Differentiating w.r.t. σe2 yields:

Notice that plugging the last result into the E-step, the last term of the E-step expression becomes constant:

|

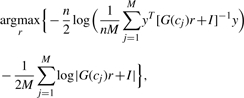

so the optimization problem for r becomes:

|

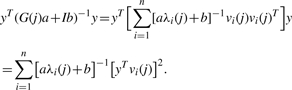

which has no closed form solution. However, given the spectral decomposition of each G(j) it is easy to solve numerically. G(j) is a correlation matrix and therefore has n real and non-negative eigenvalues. Let {λi(j)}i=1n denote the eigenvalues of a matrix G(j) associated with eigenvectors {vi(j)}i=1n, then for all a,b:

and:

|

It is useful to denote wi(j)=[yTvi(j)]2.

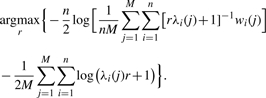

Hence, the maximized function is easy to compute when the spectral decomposition of each G(j) is known by setting a=r,b=1 and solving the following maximization problem:

|

Recall that the densities ϕ(y;G(j),σg2,σe2) are computed during the MCMC process for each G(j) matrix used. Computing the normal likelihood involves inverting the variance–covariance matrix G(j)σg2+Iσe2 which takes O(n3) operations. Using the previous results, we can easily compute the log likelihood given the spectral decomposition by setting a=σg2 and b=σe2:

|

Since obtaining the spectral decomposition is also done in O(n3), we can compute the spectral decomposition and use it for the likelihood calculations as well as for constructing the optimization problem for r with hardly any additional complexity cost. Doing so, the complexity of the optimization of r is negligible compared to the time complexity of the spectral decomposition and the MCMC burn-in.

2.7 Simulation settings

In order to test our method on data with realistic LD structure, we used HapGen (Spencer et al., 2009) to simulate 700 genotypes of 10 000 SNPs each, roughly corresponding to every 10th SNP of the first 100 000 HapMap SNPs on chromosome 1, thus simulating the same SNP density as in the data used by Yang et al. (2010). Given a desired proportion of causal SNPs p and a set of variances σg2,σe2, each SNP was chosen to be causal with probability p independently of other SNPs. Following that, the genetic correlation matrix G was calculated, and the phenotypes were sampled from N(0,Gσg2+Iσe2). It is important to note that, due to the randomization process, setting the value of σg2,σe2 or p to a certain value does not necessarily imply that the actual values of the parameters in-sample would be the same. To avoid confusion, we use the term ‘population value’ to note the value of the parameters used to generate the data, and ‘in-sample value’ to note the parameters in each sample.

The length of the burn-in period of each MCMC step, which is used to estimate the E-step, was determined using Geweke's convergence diagnostics (Geweke, 1992). We then collected 2000 samples by taking every 500th sample from the MCMC process before proceeding to the M-step.

We began by studying the convergence of the MCEM estimators. Towards this end, we set the expected variances to σg2=σe2=1 and simulated a single set of phenotypes. Then, initializing the proportion of causal SNPs (denoted p0) at its population value p, we set the initial estimators of the variance components to a range of values between 0.2 and 2 (in 0.2 intervals) thus creating a 10×10 grid of initial values around the expected values. We then ran the algorithm for 7 iterations. This exercise was repeated once with p=1% and once with p=0.1%.

A similar exercise was carried out to study the convergence properties of the estimator of the proportion of causal SNPs  , initializing the variance components estimators to their expected values and setting the actual proportion of causal SNPs to p=0.5%, we then set p0 to a range of values from 0.1% to 1% (in 0.1% intervals).

, initializing the variance components estimators to their expected values and setting the actual proportion of causal SNPs to p=0.5%, we then set p0 to a range of values from 0.1% to 1% (in 0.1% intervals).

As mentioned earlier, the method suggested by Yang et al. (2010) approximates the actual genetic correlation matrix G by a modification to the observed correlation matrix A, which is the correlation across all genotyped SNPs, causal and non-causal alike. With this in mind, we wanted to compare the methods in scenarios where this approximation is appropriate, i.e. when the proportion of causal SNPs is high, and in scenarios when the approximation would be very different from the actual G matrix, i.e. when the proportion of causal SNPs is very small. We therefore defined a ‘high’ proportion of causal SNPs to be 1% of SNPs, and a ‘low’ proportion of causal SNPs to be 0.1% of SNPs and ran two sets of 50 simulations each. In the first set, we set p=p0=1%, while in the second we set p=p0=0.1%. It is important to stress that the actual number of causal SNPs in each simulation run is not fixed to the value of p, but is distributed Bin(p,N) with N being the total number of SNPs. This means that in the aforementioned simulations the initial estimate of the proportion of causal SNPs was not necessarily the ‘correct’ (in-sample) estimate, but only close to the true value.

To test the robustness of our method to the initial estimate of the proportion of causal SNPs, we ran two more sets of simulations, one where p=1% and p0=0.1%, and one where p=0.1% and p0=1%. The four simulation scenarios were labeled A,B,C and D, respectively.

3 RESULTS

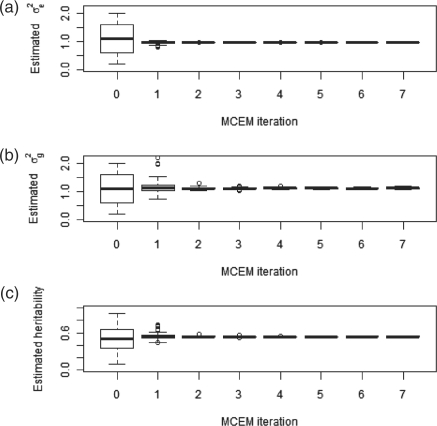

We first study the convergence properties of the MCEM algorithm. As can be seen in Figure 1, convergence is achieved after a relatively small number of iterations, after which the estimators are almost identical, independent of their starting points. Clearly, some level of variance is expected due to the stochastic nature of the MCMC approximation of the E-step, and could therefore be reduced by either taking more samples or averaging over several consecutive MCEM iterations. The number of EM iterations required for convergence did not vary greatly even when the proportion of the causal SNPs was low (data not shown). We have also found that the lengths of burn-in periods, as determined by the Geweke (1992) algorithm varied greatly between simulations and between consecutive iterations of the MCEM algorithm. In general, we have found that burn-in periods were longer when the proportion of causal SNPs was high, and shorter when the estimators were closer to their true value.

Fig. 1.

Evolution of MCEM estimators when p=1%. (a) and (b) The evolution of σe2 and σg2 estimators, starting from values ranging from 0.2 to 2 in 0.2 increments. The population value is 1 in both cases. (c) The evolution of the estimated heritability, showing a rapid convergence within a small number of iterations.

The estimators of the proportion of causal SNPs converged much slower, but did display convergence, as can be seen in Figure 2. Starting from the 10 starting points that spread uniformly in the range (0.1%, 1%), all 10 estimators were in the range (0.4%,0.7%) within 7 iterations.

Fig. 2.

The evolution of the estimator of the proportion of causal SNPs  for various starting points. Initial values range from 0.1% to 1% with increments of 0.1%. The actual value is 0.5%.

for various starting points. Initial values range from 0.1% to 1% with increments of 0.1%. The actual value is 0.5%.

We noticed that the in-sample variances, and hence the in-sample heritability, varied greatly between simulations, especially when the number of causal SNPs was small. Thus, to compare the methods we first calculated the difference between the in-sample heritability (as estimated using the actual genetic correlation matrix G generated in our simulation) and the heritability estimates obtained by the Yang et al. (2010) method and our method. An advantage of this variability of in-sample heritability is that we, in fact, compared the methods over wide range of heritability values ranging from ~0.2 to ~0.8, and not just for 0.5.

When comparing the heritability estimators obtained after 5 MCEM iterations to the estimators obtained by the Yang et al. (2010) method (Fig. 3), we found that in sets A and B, where the initial estimators of the proportion of causal SNPs were set close to the in-sample proportion, our method significantly reduced the variance of the heritability estimation errors (p<0.03 in both cases using Bartlett's test (Snedecor and Cochran, 1989)).

Fig. 3.

comparing heritability estimation errors obtained using the method suggested by Yang et al. (2010) (left box in each pair) and 5 iterations of the MCEM method (right box in each pair) for various values of the proportion of causal SNPS (p) and the initial estimate (p0). A: p=p0=1%, B: p=p0=0.1%, C: p=1%,p0=0.1% and D: p=0.1%, p0=1%.

It is important to note that while the performance of the method of Yang et al. (2010) deteriorates as the proportion of causal SNPs decreases, our method is more robust to such differences. The heritability estimation errors of Yang et al. (2010) in scenario A, where the proportion of causal SNPs is high, display a significantly lower variance than the heritability estimation errors of the same method in scenario B, when the proportion of causal SNPs is low (p<10−3). This is reasonable, as a lower proportion of causal SNPs means that the approximation of G used by the method of Yang et al. (2010) is less appropriate. Our method explicitly models the causal SNPs, and therefore we expected it to be less affected by this problem. Indeed, while our method does show higher estimation error variance in scenario B, the difference between the variances in scenarios A and B is not significant.

When initializing the estimate of the proportion of causal SNPs at a very different value, as in scenarios C and D, we saw a significant reduction in heritability estimation error from using our method only for scenario D(p<0.03). We suspect this is due to slow convergence of the estimators of p in scenario C, as discussed later.

It is also interesting to note that the estimation errors of the environmental random effects variance were smaller than the estimation errors of the genetic random effects variance. This was true for both methods and for all simulation scenarios, as well as for the convergence studies we conducted earlier. We suggest that this is because the environmental random effects are uncorrelated while the genetic random effects are correlated (with G as the correlation matrix) and thus provide a more difficult estimation problem.

3.1 Estimation of the proportion of causal SNPs

In scenarios A and B, in which the estimators of the proportion of causal SNPs were initialized to a value close to the true in-sample proportion, the estimators quickly converged. For the estimation error, the 95% confidence intervals (the difference between the estimated proportion and the in-sample proportion) are given by (−0.098%,0.075%) and (−0.013%,0.2%) for scenarios A and B, respectively (using inter-quantile range).

In scenarios C and D, the estimators of the proportion of causal SNPs did not seem to converge, but in both cases all 100 estimators were closer to the expected value than the starting point, suggesting that given enough running time they, too, would have converged. Convergence was slower for scenario C, probably explaining the non significant change in heritability estimation error variance. The 95% confidence intervals for the estimation error of the proportion of causal SNPs in scenarios C and D are given by (−0.69%,−0.53%) and (−0.2%,0.6%), respectively. Note that in both cases the estimation error is significantly smaller than the estimation error of the initial estimator, which is 0.9%. We suspect that the high LD between SNPs allows finding sets of SNPs with different sizes which lead to a similar genetic correlation matrix, for example, by adding SNPs which are approximately a convex linear combination of other SNPs. We believe this slows the convergence of the estimators of the proportion of causal SNPs, and can be solved by running more iterations of the MCEM algorithm.

4 DISCUSSION

The idea of using random effects models for analyzing genetic data is appealing and powerful. Even when only tag SNPs are genotyped, the high LD between tag SNPs and ungenotyped SNPs allows us to expect it to yield accurate results. However, the method suggested by Yang et al. (2010) might carry some hidden pitfalls. Replacing the correct genetic correlation matrix by a different matrix estimated from the data as if the latter matrix were the correct matrix is unfounded statistically. Indeed, using the A* matrix as the variance–covariance matrix introduces two additional sources of variance to the estimation. One is the error originating from the element-wise difference between A* and G (the noise from the non-causal variants) and one stems from the built-in variance of the estimated β. The former in particular is highly sensitive to the proportion of causal SNPs, as our simulations have demonstrated: with few causal SNPs, the noise in A* overwhelms the signal and estimation accuracy in the approach of Yang et al. (2010) deteriorates significantly. Ignoring both sources of variances would lead to inaccurate estimation and incorrect inference (overly optimistic confidence intervals).

Our approach avoids these issues by performing maximum likelihood-estimation of the relevant parameters: the genetic and environmental effects (variances) and the proportion of causal SNPs. To intuitively understand how this is accomplished, it is beneficial to think of the Metropolis algorithm used in the MCMC evaluation of the E-step as a ‘soft’ simulated annealing optimization scheme where we always switch to a SNP combination with higher likelihood, but switch to a lower likelihood combination with a probability that depends on the likelihood ratio. We thus expect the MCMC to visit often high-likelihood areas of the search space, corresponding to combinations of candidate causal SNPs that lead to good estimation. The M-step combines all these good combinations to estimate the parameters.

Convergence of EM in general, and MCEM in particular, to the true maximum-likelihood estimates is hard to guarantee and test (Boyles, 1983; Wu, 1983). Our simulations present evidence that the estimators of the variance components and heritability do, in fact, converge quickly to the neighborhood of the true value of the parameters, and provide some evidence that the estimator of the proportion of causal SNPs also converges. Some variance of the estimators is of course due to the Monte-Carlo nature of the MCMC approximation of the E-step and can be reduced either by taking more samples from the MCMC process, or by averaging consecutive EM iterations. More extensive research and simulations would be required to establish clear criteria for how long to run the algorithm in order to obtain optimal tradeoff between accuracy and computation time.

Putting aside the theoretical difficulties with convergence of EM, maximum-likelihood estimates possess many desirable qualities, which facilitate accurate estimation and statistical inference (Lehmann and Casella, 1998). In particular they are consistent and asymptotically normal. Moreover, once the process converges we can easily extract the information matrix (Meilijson, 1989), with which we can construct asymptotically accurate confidence intervals and carry out proper statistical inference.

Running times of the MCEM estimation are governed by two main factors: the number of individuals and the number of genotyped SNPs. Our current simulations have dealt with a toy example of 700 individuals and 10 000 SNPs. Current running times of the MCEM algorithm would render it difficult, but not impossible, to estimate the heritability when using a realistic number of genotyped SNPs. Since the lion's share of running time is ‘wasted’ on burn-in iterations (over 90% in most runs) before the MCMC process converges (as indicated by the convergence diagnostics of Geweke, 1992), we believe that smarter initialization of the MCMC process could reduce running times by an order of magnitude or more. Increasing the number of individuals is more problematic, as the time-complexity is cubic in the number of individuals, since every MCMC step involves computing the likelihood, and hence the inversion of a n×n matrix. We have shown that with even a small number of individuals our method produces very accurate estimates. Moreover, as noted earlier, the main bottleneck of the estimation is the eigenvector–eigenvalue decomposition, which is done in each MCMC iteration. The time complexity of this decomposition can be reduced from O(n3) to O(n2) using parallel algorithms (see, for example, Bientinesi et al., 2006). We therefore believe that using the MCEM method for heritability estimation in realistic databases is definitely feasible.

It is also appealing to think of replacing the ‘soft’ EM scheme we propose by a ‘hard’ EM, where in each M-step the parameters are estimated using the combination of SNPs with the highest likelihood encountered. In this case the Metropolis algorithm represents a simulated annealing optimization scheme. This setup has the advantage of also offering a possible identification of the set of causal SNPs, in addition to parameter estimation. We also expect such an approach to dramatically reduce running times. However, the hard approach is not a proper EM algorithm and is not as theoretically based as the standard EM approach. Therefore, it does not possess the favorable properties of EM estimators. We aim to study this alternative as means of reducing running times. Another alternative is to adopt a Bayesian approach altogether, as suggested by Guan,Y. and Stephens,M. (submitted for publication). The two approaches are not necessarily exclusive, as one might use the Bayesian estimate as a good starting point for the MCEM algorithm to reduce running times.

In this article, we have concentrated on the application of random effects linear regression models for estimating heritability of quantitative traits like height. While this application area is clearly important, many of the phenotypes of interest in current research are dichotomous, like disease status. The extension to the linear regression approach that would apply in such cases would be to apply random-effects generalized linear models (Breslow and Clayton, 1993), such as logistic regression. This direction presents significant complications because of fundamental differences in the statistical setup between linear random effects models and their generalized counterparts and the complexities involved in estimation methods of the latter (for example a MCEM algorithm by McCulloch, 1990). We intend to pursue this direction further in future work.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank Ronny Luss for helpful discussions.

Funding: Open Collaborative Research grant from IBM; Israeli Science Foundation (grant 1227/09); European Research Commission (grant MIRG-CT-2007-208019); Fellowship from the Edmond J. Safra Bioinformatics program at Tel-Aviv university (to D.G., in part).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Bientinesi P., et al. A parallel eigensolver for dense symmetric matrices based on multiple relatively robust representations. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. T. 2006;27:43–66. [Google Scholar]

- Boyles R.A. On the convergence of the EM algorithm. J. R. Stat. Soc. 1983;45:47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Breslow N.E., Clayton D.G. Approximate inference in generalized linear mixed models. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1993;88:9–25. [Google Scholar]

- Dempster A.P, et al. Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the EM algorithm. J. R. Stat. Soc. 1977;39:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Geweke J. Evaluating the accuracy of sampling-based approaches to calculating posterior moments. In: Bernado J.M., et al., editors. Bayesian Statistics 4. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press; 1992. pp. 169–193. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein D.B. Common genetic variation and human traits. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:1696–1698. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0806284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudbjartsson D.F., et al. Many sequence variants affecting diversity of adult human height. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:609–615. doi: 10.1038/ng.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill W.G., et al. Data and theory point to mainly additive genetic variance for complex traits. PLOS Genet. 2008;4:e1000008. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann E.L., Casella G. Theory of Point Estimation. 2. New York: Springer; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lettre G., et al. Identification of ten loci associated with height highlights new biological pathways in human growth. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:584–591. doi: 10.1038/ng.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macgregor S., et al. Bias, precision and heritability of self-reported and clinically measured height in Australian twins. Hum. Genet. 2006;120:571–580. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0240-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manolio T.A., et al. Finding the missing heritability of complex diseases. Nature. 2008;461:747–753. doi: 10.1038/nature08494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCulloch C.E. Maximum likelihood algorithms for generalized linear mixed models. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1990;92:699–704. [Google Scholar]

- Meilijson I. A fast improvement to the EM algorithm on its own terms. J. R. Stat. Soc. 1989;51:127–138. [Google Scholar]

- Searle S.R., et al. Variance Components. 1st. New York: Wiley-Interscience; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Snedecor G.W., Cochran W.G. Statistical Methods. 8th. Ames, Iowa, USA.: Iowa State University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer C.C.A., et al. Designing genome-wide association studies: sample size, power, imputation, and the choice of genotyping chip. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000477. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weedon M.N., et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies 20 loci that influence adult height. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:575–583. doi: 10.1038/ng.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei G.C.G., Tanner M.A. A Monte Carlo implementation of the EM algorithm and the Poor Man's Data augmentation algorithms. J. Amer. Stat. Assoc. 1990;85:699–704. [Google Scholar]

- Wu J.C.F. On the convergence properties of the EM algorithm. Ann. Stat. 1983;11:95–103. [Google Scholar]

- Visscher P.M., et al. Heritability in the genomics era - concepts and misconceptions. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008;9:255–265. doi: 10.1038/nrg2322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visscher P.M. Sizing up human height variation. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:489–490. doi: 10.1038/ng0508-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., et al. Common SNPs explain a large proportion of the heritability for human height. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:565–569. doi: 10.1038/ng.608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]