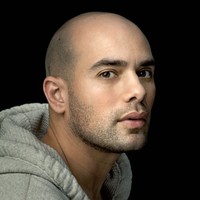

Michael Carosone

Michael Carosone is a writer, educator, activist, and native New Yorker from Kings Bay/Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn. He wrote and edited the book, Our Naked Lives: Essays from Gay Italian-American Men (published by Bordighera Press, May 2013), which is a collection of 15 personal essays from 15 men about being Gay and Italian-American. His essay appears in the book. His poems and essays have been published in a variety of books and journals. His poems have appeared in Gay City Volume 1, Gay City Volume 2, Gay City Volume 3, Avanti Popolo: Italian-American Writers Sail Beyond Columbus, The Gay and Lesbian Review, Out of Sequence: The Sonnets Remixed, The Good Men Project, Positive Lite, HIV Here and Now, and New Verse News. His essays have appeared in in White Crane, Strangers to These Shores, and various anthologies. His articles have appeared in Gay City News and The Huffington Post. He was awarded the Editors’ Poetry Prize for his work in Gay City Volume 2. He writes on personal, political, and social topics and issues, including marginalized peoples and literatures, especially Italian-Americans and people of the gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender and queer (GLBTQ) community. At various conferences nationwide, he has presented papers on LGBTQ Italian-Americans. As an adjunct faculty member since 1999, he has taught composition, creative writing, English education, ethnic studies, film, gender and sexuality studies, humanities, library literacy and research, and various types of literature at seven colleges in the New York City metropolitan area. He is a doctoral fellow in the Ph.D. program in English at St. John’s University in Queens, New York City. His current research focuses on the transformative, empowering, and political acts of reading and writing LGBTQ literature. After completing the coursework for the Doctor of Education (Ed.D.) degree in English Education at Teachers College of Columbia University, he earned an Ed.M. in English Education from Teachers College, and decided to leave that program for the Ph.D. in English at St. John’s University. His Ed.D. research focused on the purposes and transformative powers of LGBTQ literature on its LGBTQ readers and writers, the effects of teaching LGBTQ literature in the English classroom, and incorporating marginalized literatures and writers—LGBTQ and Italian American—into the English classroom, in grades K-12 and at the college level. Michael earned a B.A. and an M.A. in English from Brooklyn College; an M.S. in School Administration and Supervision from Touro College; and an M.S. in Library and Information Science from Long Island University. He lives in the Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood of Manhattan.

less

InterestsView All (250)

Uploads

Books by Michael Carosone

Previous issues of The St. John’s University Humanities Review mainly focused on book reviews, essays, and interviews. With this issue, I wanted to do something different, so I also asked for personal stories and essays that answered the question: How do you define and/or use the humanities as activism?

In the middle of May of 2016, when I was asked to edit this issue of the journal, I said yes. But what I didn’t say was that I truly didn’t want to do it, and that I didn’t think that I was capable of doing it. This was because I felt that I had nothing new to say about the humanities that had not already been said ad nauseam.

Then, in June, 49 people were killed at the LGBTQ nightclub, Pulse, on “Latin Night,” in Orlando, Florida. And I knew that homophobia shot those bullets.

Then, in July, two more Black men—Philando Castile and Alton Sterling—were killed by the police. And I knew that racism shot those bullets.

For me, it was a summer of attending vigils and protests. And I observed that the various disciplines of the arts and humanities were explicitly being utilized as activism in the streets at these vigils and protests. Specific language on protest signs. Writers reading poems at rallies. Performance artists theatrically marching. Etc. The summer of 2016 proved the value of the humanities. Nothing more to debate!

This idea of the humanities as activism is not a new one for me because for many years, in my own work, I have been connecting the two. But I noticed that it was obvious that others realized that the two were inextricable. And that was when I knew that I had something new to say about the humanities, and that I would use this issue to say it.

And then Trump won the election.

One of the many wonderful things that feminism taught me was that the personal is political. I chose the theme of “The Humanities As Activism” for this issue of the journal because it is personal. It truly is that simple. I believe that in order to improve our current social-political problems, we must make use of the humanities as activism. The arts and humanities must be utilized as agents of change.

As I edit this issue, I keep re-reading two of Dorothy Allison’s essays (for inspiration): “Believing in Literature,” in which she tells us that “literature should push people to change the world”; and “Survival Is the Least of My Desires,” in which she writes: “I became convinced that to survive I would have to re-make the world so that it came closer to matching its own ideals.” I think that it is time that all of us start to re-make this cruel world. And I think that the contributors in this issue of the journal agree with me; they, too, are trying to re-make this world.

What you are about to read are forceful pieces that demand and deserve the same attention that we would give to any energizing speech at a protest rally. So, with your fists up, voices screaming, and feet marching, I hope that you enjoy the journey and movement that is this issue of The St. John’s University Humanities Review. The revolution is coming and it is documented in this journal.

In solidarity,

Michael Carosone, Editor

New York City, May 2017

Dedicated to the activists, artists, humanists, scholars, and writers,

to the oppressed and marginalized,

to the victims.

Dedicated to revealing the truth.

“The arts [humanities], it has been said, cannot change the world, but they may change human beings who might change the world.”

–Maxine Greene

Previous issues of The St. John’s University Humanities Review mainly focused on book reviews, essays, and interviews. With this issue, I wanted to do something different, so I also asked for personal stories and essays that answered the question: How do you define and/or use the humanities as activism?

In the middle of May of 2016, when I was asked to edit this issue of the journal, I said yes. But what I didn’t say was that I truly didn’t want to do it, and that I didn’t think that I was capable of doing it. This was because I felt that I had nothing new to say about the humanities that had not already been said ad nauseam.

Then, in June, 49 people were killed at the LGBTQ nightclub, Pulse, on “Latin Night,” in Orlando, Florida. And I knew that homophobia shot those bullets.

Then, in July, two more Black men—Philando Castile and Alton Sterling—were killed by the police. And I knew that racism shot those bullets.

For me, it was a summer of attending vigils and protests. And I observed that the various disciplines of the arts and humanities were explicitly being utilized as activism in the streets at these vigils and protests. Specific language on protest signs. Writers reading poems at rallies. Performance artists theatrically marching. Etc. The summer of 2016 proved the value of the humanities. Nothing more to debate!

This idea of the humanities as activism is not a new one for me because for many years, in my own work, I have been connecting the two. But I noticed that it was obvious that others realized that the two were inextricable. And that was when I knew that I had something new to say about the humanities, and that I would use this issue to say it.

And then Trump won the election.

One of the many wonderful things that feminism taught me was that the personal is political. I chose the theme of “The Humanities As Activism” for this issue of the journal because it is personal. It truly is that simple. I believe that in order to improve our current social-political problems, we must make use of the humanities as activism. The arts and humanities must be utilized as agents of change.

As I edit this issue, I keep re-reading two of Dorothy Allison’s essays (for inspiration): “Believing in Literature,” in which she tells us that “literature should push people to change the world”; and “Survival Is the Least of My Desires,” in which she writes: “I became convinced that to survive I would have to re-make the world so that it came closer to matching its own ideals.” I think that it is time that all of us start to re-make this cruel world. And I think that the contributors in this issue of the journal agree with me; they, too, are trying to re-make this world.

What you are about to read are forceful pieces that demand and deserve the same attention that we would give to any energizing speech at a protest rally. So, with your fists up, voices screaming, and feet marching, I hope that you enjoy the journey and movement that is this issue of The St. John’s University Humanities Review. The revolution is coming and it is documented in this journal.

In solidarity,

Michael Carosone, Editor

New York City, May 2017

Dedicated to the activists, artists, humanists, scholars, and writers,

to the oppressed and marginalized,

to the victims.

Dedicated to revealing the truth.

“The arts [humanities], it has been said, cannot change the world, but they may change human beings who might change the world.”

–Maxine Greene

Immediately, Michael found copies of those two books, and that evening, he explained to Joseph his frustration about the double marginalization of Gay Italian American literature. That was the conversation that started the idea for this collection of personal essays from a diverse group of Gay Italian American men.

Joseph’s response was filled with the same disappointment and anger because he, too, realized the absence of Gay Italian American identities and voices in the curriculum during his own studies in psychology and social work. However, during his undergraduate years at Columbia University, Joseph’s Italian American identity was very much present when his fellow classmates typically stereotyped him as an ignorant blue-collar, working class guido from Bensonhurst, with his family in the mafia, who did not deserve acceptance to an Ivy League institution.

So, we talked about how both of our identities—Gay and Italian American—never appeared throughout our years of formal education. Those two characters were never written in the scenes; those two actors were never given roles on the stage. And we wondered how much longer this would continue, and how much more we were able to tolerate.

Here are two stereotypes: one, the Italian American community is perceived as ignorant, stupid, unsophisticated, uncultured, blue-collar, working class, and connected to the mafia; two, the gay community is perceived as intelligent, sophisticated, cultured, creative, white-collar, and high class. Thus, a contradiction is formed, creating identity crises among Queer Italian American men and women.

Furthermore, in the mainstream, heterosexual society, the stereotype for the Italian American male is a man who is macho, strong, tough, brutish, violent, uneducated, handsome, sexy, and virile, with a big penis and an even bigger sex drive. Thus, commonly, Gay Italian American men distance themselves from their ethnic selves because they cannot, and do not want to, fulfill the stereotype of the Italian American male.

Contrary to the negative stereotype, Gay men can be macho; however, Gay Italian American men do not want to associate themselves with the negative stereotype of Italian American male machismo. Therefore, they denounce their ethnic halves because they do not feel comfortable in/with their own families and ethnic communities. They disconnect from their Italian American history, heritage, and culture. They give themselves fully to their homosexual selves because they are more accepted in their queer communities. However, they are only accepted as non-ethnic, white gay men, not as ethnic Italian American Gay men, who can also identify as non-white if they so choose to do so.

We have noticed a lack of ethnic pride between Gay Italian American men. Hence, gay Italian American male writers write about their gay lives, communities, culture, and history, but not about their Italian American lives, communities, culture, history, and heritage. Such an identity crisis must be solved and corrected by both communities: the Gay Community and the Italian American Community. Furthermore, such stereotypes are debilitating for, both, the individuals and the communities.

It must also be stated that such issues do not occur only in the ethnic Italian American community, but in many ethnic communities, as homosexuality is still not accepted, tolerated, and understood in many communities and societies.

Ethnicity and homosexuality can be viewed as mutually exclusive, and when the two interact, they create a conflicted relationship. And it is the conflict that must be resolved in order for a Queer Italian American to live a healthy and fulfilled life, in which he/she is proud and accepting of, both, his/her ethnicity and sexuality.

In the mainstream literary world, and in society in general, there exists levels of marginalization within one already marginalized ethnic community: first, all Italian American writers, regardless of gender, are marginalized; second, Italian American women writers are marginalized even more because of their gender; and third, queer Italian American writers are marginalized even further because of their sexual orientation.

A major, reoccurring theme in Gay Italian American literature is rejection. Queer Italian American writers—and their characters—are rejected because they refuse to conform to the traditions, mostly religious, of their families. They feel like outsiders. They are ostracized and oppressed because they are different. They become alone and lonely. Ironically, in essence, they are treated the same way their immigrant ancestors were treated by the mainstream society when they arrived in America from Italy.

Although Americans of the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (GLBTQ) community and population have made great strides, their futures, at times, seem uncertain, insecure, and grim because of the heterosexist society in which they live. Their civil rights continue to be debated and threatened.

The Gay Community, to no fault of its own, is a group of which many different types of people belong, from many different walks of life. It is unique in that, unlike any other group of people, its members come from every group of people, from every race, religion, class, and culture. Usually, the only thing that homosexuals have in common is that they are attracted to the same sex. Thus, ethnicity is easily overlooked in the gay community. And lately, queer men and women are fighting for their civil rights, so their ethnic rights are not a priority.

The purpose of this book is to present these essays that inform on the experiences of these men and their lives as part of the diverse fabric of American society. The lives of these writers are complex because they are forced to conform into a society that demands that they do not express their sexual and ethnic identities, with pride, in positive ways. As sexual and ethnic minorities, these men experience double discrimination.

Many people will ask why this book is important and unique, and why this group of men is important and unique. Our answer to that often ubiquitous and trite question is this: Our identities, voices, words, and lives are important and unique because the intersection of our sexuality and ethnicity does not allow us to fit in to the mainstream American society and culture, thereby keeping us in the margins. And it should be common sense and common knowledge by now, in the twenty-first century, that no human being deserves to be marginalized for any reason.

This book has been a labor of love for us since 2008, and we hope that our readers take this journey with us, and appreciate the important lives and words of our contributors.

Conference Presentations by Michael Carosone

Papers by Michael Carosone

How Do We Stop LGBTQ Youth from Killing Themselves? The answer is simple: Literature!

During the spring semester of 2002, while teaching my creative writing class at Sheepshead Bay High School in Brooklyn, New York, Paul (let’s call him Paul) finally shared and read aloud a poem that he had just written in class. After not wanting to share and read aloud any of his writing for months, Paul eagerly expressed that he had to be the first student to read his poem to the class. With surprise, curiosity, and interest, the other students and I happily wanted Paul to be the first one to read his poem. And after he read, our jaws dropped with amazement, our eyes widened with shock, our brows curled with concern, our hearts stopped with empathy, and our bodies froze with fear. Paul had just revealed that he wanted to commit suicide. In his poem—his work of literature—Paul exposed his vulnerability and humanity, and expressed his deep dark desire to end his life. Paul used literature for his own purpose. This is the power of literature!

Previous issues of The St. John’s University Humanities Review mainly focused on book reviews, essays, and interviews. With this issue, I wanted to do something different, so I also asked for personal stories and essays that answered the question: How do you define and/or use the humanities as activism?

In the middle of May of 2016, when I was asked to edit this issue of the journal, I said yes. But what I didn’t say was that I truly didn’t want to do it, and that I didn’t think that I was capable of doing it. This was because I felt that I had nothing new to say about the humanities that had not already been said ad nauseam.

Then, in June, 49 people were killed at the LGBTQ nightclub, Pulse, on “Latin Night,” in Orlando, Florida. And I knew that homophobia shot those bullets.

Then, in July, two more Black men—Philando Castile and Alton Sterling—were killed by the police. And I knew that racism shot those bullets.

For me, it was a summer of attending vigils and protests. And I observed that the various disciplines of the arts and humanities were explicitly being utilized as activism in the streets at these vigils and protests. Specific language on protest signs. Writers reading poems at rallies. Performance artists theatrically marching. Etc. The summer of 2016 proved the value of the humanities. Nothing more to debate!

This idea of the humanities as activism is not a new one for me because for many years, in my own work, I have been connecting the two. But I noticed that it was obvious that others realized that the two were inextricable. And that was when I knew that I had something new to say about the humanities, and that I would use this issue to say it.

And then Trump won the election.

One of the many wonderful things that feminism taught me was that the personal is political. I chose the theme of “The Humanities As Activism” for this issue of the journal because it is personal. It truly is that simple. I believe that in order to improve our current social-political problems, we must make use of the humanities as activism. The arts and humanities must be utilized as agents of change.

As I edit this issue, I keep re-reading two of Dorothy Allison’s essays (for inspiration): “Believing in Literature,” in which she tells us that “literature should push people to change the world”; and “Survival Is the Least of My Desires,” in which she writes: “I became convinced that to survive I would have to re-make the world so that it came closer to matching its own ideals.” I think that it is time that all of us start to re-make this cruel world. And I think that the contributors in this issue of the journal agree with me; they, too, are trying to re-make this world.

What you are about to read are forceful pieces that demand and deserve the same attention that we would give to any energizing speech at a protest rally. So, with your fists up, voices screaming, and feet marching, I hope that you enjoy the journey and movement that is this issue of The St. John’s University Humanities Review. The revolution is coming and it is documented in this journal.

In solidarity,

Michael Carosone, Editor

New York City, May 2017

Dedicated to the activists, artists, humanists, scholars, and writers,

to the oppressed and marginalized,

to the victims.

Dedicated to revealing the truth.

“The arts [humanities], it has been said, cannot change the world, but they may change human beings who might change the world.”

–Maxine Greene

Previous issues of The St. John’s University Humanities Review mainly focused on book reviews, essays, and interviews. With this issue, I wanted to do something different, so I also asked for personal stories and essays that answered the question: How do you define and/or use the humanities as activism?

In the middle of May of 2016, when I was asked to edit this issue of the journal, I said yes. But what I didn’t say was that I truly didn’t want to do it, and that I didn’t think that I was capable of doing it. This was because I felt that I had nothing new to say about the humanities that had not already been said ad nauseam.

Then, in June, 49 people were killed at the LGBTQ nightclub, Pulse, on “Latin Night,” in Orlando, Florida. And I knew that homophobia shot those bullets.

Then, in July, two more Black men—Philando Castile and Alton Sterling—were killed by the police. And I knew that racism shot those bullets.

For me, it was a summer of attending vigils and protests. And I observed that the various disciplines of the arts and humanities were explicitly being utilized as activism in the streets at these vigils and protests. Specific language on protest signs. Writers reading poems at rallies. Performance artists theatrically marching. Etc. The summer of 2016 proved the value of the humanities. Nothing more to debate!

This idea of the humanities as activism is not a new one for me because for many years, in my own work, I have been connecting the two. But I noticed that it was obvious that others realized that the two were inextricable. And that was when I knew that I had something new to say about the humanities, and that I would use this issue to say it.

And then Trump won the election.

One of the many wonderful things that feminism taught me was that the personal is political. I chose the theme of “The Humanities As Activism” for this issue of the journal because it is personal. It truly is that simple. I believe that in order to improve our current social-political problems, we must make use of the humanities as activism. The arts and humanities must be utilized as agents of change.

As I edit this issue, I keep re-reading two of Dorothy Allison’s essays (for inspiration): “Believing in Literature,” in which she tells us that “literature should push people to change the world”; and “Survival Is the Least of My Desires,” in which she writes: “I became convinced that to survive I would have to re-make the world so that it came closer to matching its own ideals.” I think that it is time that all of us start to re-make this cruel world. And I think that the contributors in this issue of the journal agree with me; they, too, are trying to re-make this world.

What you are about to read are forceful pieces that demand and deserve the same attention that we would give to any energizing speech at a protest rally. So, with your fists up, voices screaming, and feet marching, I hope that you enjoy the journey and movement that is this issue of The St. John’s University Humanities Review. The revolution is coming and it is documented in this journal.

In solidarity,

Michael Carosone, Editor

New York City, May 2017

Dedicated to the activists, artists, humanists, scholars, and writers,

to the oppressed and marginalized,

to the victims.

Dedicated to revealing the truth.

“The arts [humanities], it has been said, cannot change the world, but they may change human beings who might change the world.”

–Maxine Greene

Immediately, Michael found copies of those two books, and that evening, he explained to Joseph his frustration about the double marginalization of Gay Italian American literature. That was the conversation that started the idea for this collection of personal essays from a diverse group of Gay Italian American men.

Joseph’s response was filled with the same disappointment and anger because he, too, realized the absence of Gay Italian American identities and voices in the curriculum during his own studies in psychology and social work. However, during his undergraduate years at Columbia University, Joseph’s Italian American identity was very much present when his fellow classmates typically stereotyped him as an ignorant blue-collar, working class guido from Bensonhurst, with his family in the mafia, who did not deserve acceptance to an Ivy League institution.

So, we talked about how both of our identities—Gay and Italian American—never appeared throughout our years of formal education. Those two characters were never written in the scenes; those two actors were never given roles on the stage. And we wondered how much longer this would continue, and how much more we were able to tolerate.

Here are two stereotypes: one, the Italian American community is perceived as ignorant, stupid, unsophisticated, uncultured, blue-collar, working class, and connected to the mafia; two, the gay community is perceived as intelligent, sophisticated, cultured, creative, white-collar, and high class. Thus, a contradiction is formed, creating identity crises among Queer Italian American men and women.

Furthermore, in the mainstream, heterosexual society, the stereotype for the Italian American male is a man who is macho, strong, tough, brutish, violent, uneducated, handsome, sexy, and virile, with a big penis and an even bigger sex drive. Thus, commonly, Gay Italian American men distance themselves from their ethnic selves because they cannot, and do not want to, fulfill the stereotype of the Italian American male.

Contrary to the negative stereotype, Gay men can be macho; however, Gay Italian American men do not want to associate themselves with the negative stereotype of Italian American male machismo. Therefore, they denounce their ethnic halves because they do not feel comfortable in/with their own families and ethnic communities. They disconnect from their Italian American history, heritage, and culture. They give themselves fully to their homosexual selves because they are more accepted in their queer communities. However, they are only accepted as non-ethnic, white gay men, not as ethnic Italian American Gay men, who can also identify as non-white if they so choose to do so.

We have noticed a lack of ethnic pride between Gay Italian American men. Hence, gay Italian American male writers write about their gay lives, communities, culture, and history, but not about their Italian American lives, communities, culture, history, and heritage. Such an identity crisis must be solved and corrected by both communities: the Gay Community and the Italian American Community. Furthermore, such stereotypes are debilitating for, both, the individuals and the communities.

It must also be stated that such issues do not occur only in the ethnic Italian American community, but in many ethnic communities, as homosexuality is still not accepted, tolerated, and understood in many communities and societies.

Ethnicity and homosexuality can be viewed as mutually exclusive, and when the two interact, they create a conflicted relationship. And it is the conflict that must be resolved in order for a Queer Italian American to live a healthy and fulfilled life, in which he/she is proud and accepting of, both, his/her ethnicity and sexuality.

In the mainstream literary world, and in society in general, there exists levels of marginalization within one already marginalized ethnic community: first, all Italian American writers, regardless of gender, are marginalized; second, Italian American women writers are marginalized even more because of their gender; and third, queer Italian American writers are marginalized even further because of their sexual orientation.

A major, reoccurring theme in Gay Italian American literature is rejection. Queer Italian American writers—and their characters—are rejected because they refuse to conform to the traditions, mostly religious, of their families. They feel like outsiders. They are ostracized and oppressed because they are different. They become alone and lonely. Ironically, in essence, they are treated the same way their immigrant ancestors were treated by the mainstream society when they arrived in America from Italy.

Although Americans of the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (GLBTQ) community and population have made great strides, their futures, at times, seem uncertain, insecure, and grim because of the heterosexist society in which they live. Their civil rights continue to be debated and threatened.

The Gay Community, to no fault of its own, is a group of which many different types of people belong, from many different walks of life. It is unique in that, unlike any other group of people, its members come from every group of people, from every race, religion, class, and culture. Usually, the only thing that homosexuals have in common is that they are attracted to the same sex. Thus, ethnicity is easily overlooked in the gay community. And lately, queer men and women are fighting for their civil rights, so their ethnic rights are not a priority.

The purpose of this book is to present these essays that inform on the experiences of these men and their lives as part of the diverse fabric of American society. The lives of these writers are complex because they are forced to conform into a society that demands that they do not express their sexual and ethnic identities, with pride, in positive ways. As sexual and ethnic minorities, these men experience double discrimination.

Many people will ask why this book is important and unique, and why this group of men is important and unique. Our answer to that often ubiquitous and trite question is this: Our identities, voices, words, and lives are important and unique because the intersection of our sexuality and ethnicity does not allow us to fit in to the mainstream American society and culture, thereby keeping us in the margins. And it should be common sense and common knowledge by now, in the twenty-first century, that no human being deserves to be marginalized for any reason.

This book has been a labor of love for us since 2008, and we hope that our readers take this journey with us, and appreciate the important lives and words of our contributors.

How Do We Stop LGBTQ Youth from Killing Themselves? The answer is simple: Literature!

During the spring semester of 2002, while teaching my creative writing class at Sheepshead Bay High School in Brooklyn, New York, Paul (let’s call him Paul) finally shared and read aloud a poem that he had just written in class. After not wanting to share and read aloud any of his writing for months, Paul eagerly expressed that he had to be the first student to read his poem to the class. With surprise, curiosity, and interest, the other students and I happily wanted Paul to be the first one to read his poem. And after he read, our jaws dropped with amazement, our eyes widened with shock, our brows curled with concern, our hearts stopped with empathy, and our bodies froze with fear. Paul had just revealed that he wanted to commit suicide. In his poem—his work of literature—Paul exposed his vulnerability and humanity, and expressed his deep dark desire to end his life. Paul used literature for his own purpose. This is the power of literature!

In her essay, Tracy Morgan asserts that some Black religious leaders view homosexuality as yet another genocidal white import into the Black community (280). Their message is “loud and clear: to be gay is to be white” (280). She finds their logic odd because throughout the history of the United States, Blackness has been identified with sexual perversion.

From my own observations and experiences as a student in many literature classes, to observing my own colleagues teach their literature classes, whether at the high school or college level, here is an example of how certain aspects of the personal lives of the authors are introduced (or not) to students.

Or, the following information is what is included in biographical information of authors, whether in printed books or posted on the Internet.

My questions to you are:

1. What is wrong with the information that is given?

2. What is missing?

3. What is the problem?

The following three authors are examples for my experiment.

1. Toni Morrison (born Chloe Ardelia Wofford) was born in Lorain, Ohio, on February 18, 1931. In 1958 she married Harold Morrison, a Jamaican architect and fellow faculty member at Howard University. They had two children, Harold and Slade, and divorced in 1964.

2. Alice Walker was born in Eatonton, Georgia, on February 9, 1944. In 1965, Walker met Melvyn Rosenman Leventhal, a Jewish civil rights lawyer. They were married on March 17, 1967, in New York City. Walker and her husband divorced amicably in 1976.

3. Audre Lorde (born Audrey Geraldine Lorde) was born in New York City, on February 18, 1934, and died on November 17, 1992, in St. Croix.

1. How can education be a political act in a positive way?

2. How can an educator (intellectual) be an activist who effects positive change?

3. How can we be educator-activists in English Education?

4. How can we use English Education to make sure that the Holocaust never happens again?

5. How can we use literature, literacy, reading, and writing as social justice?