Abstract

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has spread rapidly worldwide, causing significant mortality. There is a mechanistic relationship between intracellular coronavirus replication and deregulated autophagosome–lysosome system. We performed transcriptome analysis of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from COVID-19 patients and identified the aberrant upregulation of genes in the lysosome pathway. We further determined the capability of two circulating markers, namely microtubule-associated proteins 1A/1B light chain 3B (LC3B) and (p62/SQSTM1) p62, both of which depend on lysosome for degradation, in predicting the emergence of moderate-to-severe disease in COVID-19 patients requiring hospitalization for supplemental oxygen therapy. Logistic regression analyses showed that LC3B was associated with moderate-to-severe COVID-19, independent of age, sex and clinical risk score. A decrease in LC3B concentration <5.5 ng/ml increased the risk of oxygen and ventilatory requirement (adjusted odds ratio: 4.6; 95% CI: 1.1–22.0; P = 0.04). Serum concentrations of p62 in the moderate-to-severe group were significantly lower in patients aged 50 or below. In conclusion, lysosome function is deregulated in PBMCs isolated from COVID-19 patients, and the related biomarker LC3B may serve as a novel tool for stratifying patients with moderate-to-severe COVID-19 from those with asymptomatic or mild disease. COVID-19 patients with a decrease in LC3B concentration <5.5 ng/ml will require early hospital admission for supplemental oxygen therapy and other respiratory support.

Keywords: COVID-19, autophagy, LC3B

Introduction

Patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), exhibit diverse clinical manifestations [1]. While 5–10% of patients develop severe respiratory distress, others remain asymptomatic or have minimal symptoms that do not require hospital admission or supplemental oxygen [2].

Autophagy is an important lysosome-dependent host defense mechanism [1]. To counteract viral infection, host autophagy not only selects viral components for lysosomal degradation but also facilitates antigen processing and adaptive immune response. However, some viruses, such as SARS-CoV, filoviruses (e.g. Ebola) and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) [3], could hijack the host autophagic machinery for intracellular viral replication and propagation [4–7]. SARS-CoV, which is genetically similar to SARS-CoV-2, has been shown to impair lysosomal function and autophagic flux in the airway epithelium [5–7]. Biologically, it is plausible that SARS-CoV-2 may encode virulence factors to escape lysosome-dependent autophagic lysis and immune surveillance. In this regard, microtubule-associated proteins 1A/1B light chain 3B (LC3B) and p62/SQSTM1 (p62) are the central proteins in the autophagic pathway, mediating autophagosome biogenesis and the removal of ubiquitinated protein aggregates, respectively [8].

Herein, we examined the involvement of the autophagosome–lysosome system by transcriptomic analysis of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) isolated from COVID-19 patients and healthy subjects, followed by gene set enrichment analysis. We further conducted a retrospective cohort study to determine the association between the circulating levels of two related markers, namely LC3B or p62, and the clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19.

Methods

Transcriptome analysis

Ribonucleicacid (RNA) sequencing datasets of PBMCs, isolated from three COVID-19 patients and three healthy controls, were obtained from the Genome Sequence Archive in BIG Data Center (https://bigd.big.ac.cn/) under the project PRJCA002326. RNA sequencing data were first evaluated by FastQC (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/) with the default parameter and were then aligned with Hisat2 (version 2.1.0) onto the human (hg38) genome guided by the GENCODE gene annotation (version 34) with the default parameters. The expression of genes in each sample was calculated by the featureCounts package (version 2.0.1) with the ‘-M’ parameter. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified using the R package EBSeq (version 1.28.0) with the following conditions: adjusted P-value < 0.05 and the absolute value of log2 fold-change > 1.

Pathway enrichment analysis

Enrichment analysis of the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway annotation was performed with the identified DEGs using the R package clusterProfiler (version 3.16.1). The Benjamini and Hochberg methods were used to correct the P-values for the false discovery rate (FDR).

Patient recruitment

We included 168 adult COVID-19 patients who were tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 with throat swabs, based on real-time reverse transcription (RT)-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) according to a standard protocol [9]. All patients were admitted to the Third People’s Hospital of Shenzhen. The study was approved by the ethics committee. The requirement for informed consent was waived as described previously [10].

Clinical data collection

We collected the patient details and clinical outcomes by reviewing patient medical records. All data were recorded on a specifically designed data collection form. To ensure data accuracy, two researchers independently reviewed the clinical notes and laboratory results. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Biomarker measurement

Blood samples were collected during the hospital stay as clinically indicated. Whole blood samples were allowed to set at 4°C for 60 min. After centrifuging at 1500× g for 10 min, the supernatant was collected and stored at −30°C until assay. Serum concentrations of two circulating autophagy-/lysosome-associated proteins, LC3B and p62, were measured using the commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Omnimabs, USA and Cloud-Clone Corp) as previously described [11]. The lowest detection limits were 0.1 ng/ml and 0.312 ng/ml for LC3B and p62, respectively.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was the use of any supplemental oxygen during the hospital stay to maintain resting oxyhemoglobin saturation ≥90%. Outcome severity was stratified as: (1) asymptomatic; (2) mild disease—had symptoms but did not require oxygen therapy; (3) moderate disease—required supplemental oxygen at ≤8 L/min and (4) severe disease—required high flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy, noninvasive or invasive ventilation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation [12, 13]. The secondary outcomes were the length of hospital stay with viral clearance until viral RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 became negative.

Statistics

Data were expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR), or range and counts with percentages, as appropriate. Differences in the clinical characteristics, outcomes and serum LC3B and p62 levels were compared between the severity of COVID-19 using t-test. The Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the baseline characteristics and outcomes where appropriate. Multiple logistic regression was used to identify the independent risk factors for moderate-to-severe COVID-19. Statistically significant clinical and laboratory variables in multivariate logistic regression were selected to construct a clinical risk score to classify patients with different outcomes. The best cut-off point for each continuous predictor was determined by the maximized Youden Index score [14]. The score of each parameter was finalized based on the odds ratio (OR) of the multivariate analysis. We also evaluated the ability of the clinical risk score by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, of which, the 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated by bootstrapping of 1000 samples. In the final model, we combined age, sex and the clinical risk score with the autophagy markers. All statistical analyses were done based on R (version 4.0, R Foundation for Statistical Computing). A P-value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

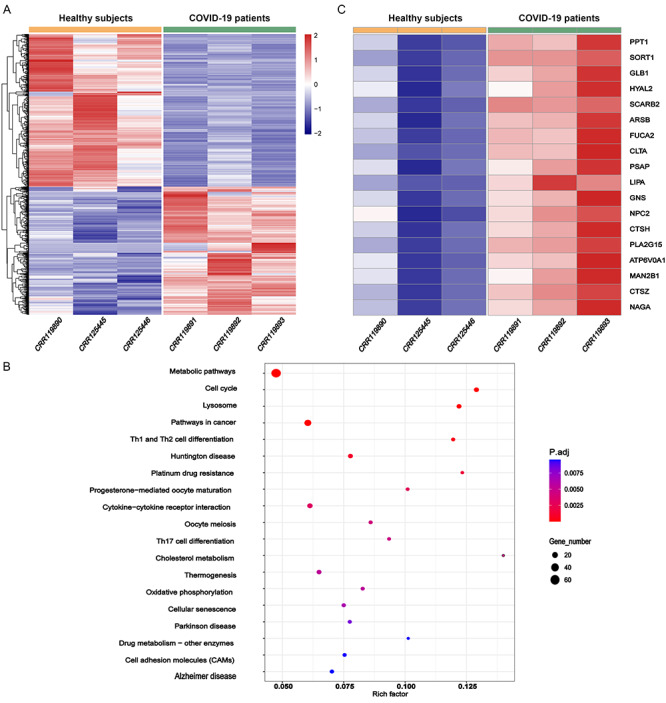

DEGs in PBMCs isolated from COVID-19 patients were enriched in cell cycle, cholesterol metabolism and the lysosome pathway

A total of 1454 DEGs (adjusted FDR-adjusted P-value < 0.01 and the absolute value of log2 fold-change > 1), namely 664 upregulated and 790 downregulated genes (Figure 1A), were identified in the PBMCs isolated from patients with COVID-19 as compared with those from healthy subjects. The top significantly enriched pathways by these COVID-19-associated DEGs were ‘cholesterol metabolism’ and ‘cell cycle’, which are implicated in the innate immune response against viral infection and lymphocyte expansion during inflammation. Interestingly, the third top pathophysiologically relevant, significantly enriched pathway by these DEGs was ‘lysosome’ (Figure 1B). Notably, most of the genes involved in the lysosome development and function were strongly upregulated (Figure 1C), suggesting a strong activation of lysosome function in the PBMCs. Eight DEGs in cholesterol metabolism were also upregulated in the PBMCs from COVID-19 patients (Supplementary Figure S1 available online at http://bib.oxfordjournals.org/).

Figure 1.

Activation of lysosome pathway in PBMCs revealed by transcriptome analysis. (A) DEGs in PBMCs isolated from three COVID-19 patients versus three healthy subjects. (B) KEGG enrichment analysis of the DEGs. (C) Upregulation of genes involved in lysosome function and biogenesis in COVID-19.

Baseline characteristics, clinical and laboratory risk factors and clinical outcomes

Next, we verified the occurrence of autophagosome–lysosome dysfunction in COVID-19 patients by measuring the circulating levels of two related markers, namely LC3B and p62. Consistent with the literature, both proteins were confirmed to be degraded by lysosomes in human monocytic cells (Supplementary Figure S2 available online at http://bib.oxfordjournals.org/). Patients were enrolled from 2 January 2020, and the last patient was followed up on 8 March 2020 (Supplementary Figure S3 available online at http://bib.oxfordjournals.org/). Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics, within 48 h of hospital admission, and Figure 2 displays the patient progress and treatment provided. A total of 77 patients (45.8%) were male and the median age was 48 (IQR: 35–61) years.

Table 1.

Demographic and epidemiologic characteristics within 48 h of admission

| Asymptomatic or mild COVID-19 | Moderate-to-severe COVID-19 | OR (95% CI) | P-value* | OR (95% CI) | P-value* | |

| (N = 81) | (N = 87) | Univariate | – | Multivariate | – | |

| Patient characteristics | ||||||

| Male sex—no. (%) | 35 (43.2) | 42 (48.3) | 0.8 (0.4–1.5) | 0.51 | 2.1 (0.9–5.3) | 0.11 |

| Median age (IQR) | 40 (33–57) | 54 (40–62) | 1.0 (1.0–1.1) | <0.001 | – | – |

| Age > 50—no. (%) | 27 (33.3) | 47 (54.0) | 2.4 (1.3–4.4) | 0.01 | 0.7 (0.3–2.0) | 0.71 |

| Median heart rate (IQR)—beats/min | 86 (78–93) | 86 (80–94) | 1.0 (0.9–1.0) | 0.35 | – | – |

| Median respiratory rate (IQR)—breaths/min | 20 (19–20) | 20 (19–20) | 1.2 (1.0–1.5) | 0.04 | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) | 0.56 |

| Median systolic blood pressure (IQR)—mmHg | 122 (113–131) | 127 (117–138) | 1.0 (1.0–1.1) | 0.02 | 1.1 (1.0–1.1) | 0.002 |

| Median diastolic blood pressure (IQR)—mmHg | 79 (74–86) | 81 (75–88) | 1.0 (0.9–1.0) | 0.22 | – | – |

| Median temperature (IQR)—°C | 36.8 (36.5–37.2) | 37.0 (36.8–37.6) | 2.1 (1.2–3.5) | 0.01 | 1.2 (0.9–2.5) | 0.59 |

| Epidemiology—no. (%) | ||||||

| Living in Hubei | 22 (27.2) | 14 (16.1) | 0.5 (0.2–1.1) | 0.08 | – | – |

| Recently visited to Hubei | 23 (28.4) | 34 (39.1) | 1.6 (0.8–3.1) | 0.15 | – | – |

| Had contact with Hubei residents | 11 (13.6) | 6 (6.9) | 0.5 (0.2–1.3) | 0.16 | – | – |

| Principle symptoms at admission—no. (%) | ||||||

| Fever | 50 (61.7) | 64 (73.6) | 1.7 (0.9–3.3) | 0.10 | – | – |

| Cough | 38 (46.9) | 45 (51.7) | 1.2 (0.7–2.2) | 0.53 | – | – |

| Sputum | 13 (16.0) | 17 (19.5) | 1.3 (0.6–2.8) | 0.56 | – | – |

| Nasal congestion | 5 (6.2) | 6 (6.9) | 1.1 (0.3–3.8) | 0.85 | – | – |

| Rhinorrhea | 5 (6.2) | 6 (6.9) | 1.1 (0.3–3.8) | 0.85 | – | – |

| Sore throat | 9 (11.1) | 16 (18.4) | 1.8 (0.7–4.3) | 0.19 | – | – |

| Chest pain or tightness | 4 (4.9) | 14 (16.1) | 3.7 (1.2–11.7) | 0.03 | 6.5 (1.5–37.3) | 0.02 |

| Dyspnea | 0 (0.0) | 6 (6.9) | – | – | – | – |

| Fatigue | 6 (7.4) | 14 (16.1) | 2.4 (0.9–6.6) | 0.09 | – | – |

| Diarrhea | 3 (3.7) | 10 (11.5) | 3.4 (0.9–12.7) | 0.07 | – | – |

| Myalgia | 5 (6.2) | 17 (19.5) | 3.7 (1.3–10.5) | 0.01 | 5.1 (1.4–21.6) | 0.02 |

| Headache | 4 (4.9) | 10 (11.5) | 2.5 (0.8–8.3) | 0.14 | – | – |

| Dizziness | 1 (1.2) | 6 (6.9) | 5.9 (0.7–50.3) | 0.10 | – | – |

| Chill and rigor | 8 (9.9) | 13 (14.9) | 1.6 (0.6–4.1) | 0.32 | – | – |

| Nausea or vomiting | 2 (2.5) | 2 (2.3) | 0.9 (0.1–6.8) | 0.94 | – | – |

| Co-morbidities—no. (%) | ||||||

| Hypertension | 8 (9.9) | 17 (19.5) | 2.2 (0.9–5.5) | 0.21 | – | – |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3 (3.7) | 6 (6.9) | 1.9 (0.5–8.0) | 0.66 | – | – |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.1) | – | 0.99 | – | – |

| Liver disease | 4 (4.9) | 7 (8.0) | 1.7 (0.5–6.0) | 0.42 | – | – |

| Coronary heart disease | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.1) | – | 0.99 | – | – |

| Tuberculosis | 2 (2.5) | 2 (2.3) | 0.9 (0.1–6.8) | 0.94 | – | – |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 3 (3.7) | 3 (3.4) | 0.9 (0.2–4.7) | 0.93 | – | – |

| Renal disease | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.3) | – | 0.99 | – | – |

| Coronary artery disease | 2 (2.5) | 3 (3.4) | 1.4 (0.2–8.7) | 0.71 | – | – |

| Laboratory result (within 48 h of admission) | ||||||

| Median white cell count (IQR)—×109 | 4.8 (3.9–6.5) | 4.6 (3.5–5.8) | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) | 0.02 | 0.7 (0.5–0.9) | 0.003 |

| Median neutrophil count (IQR)—×109 | 2.9 (2.2–3.9) | 3.0 (2.0–3.8) | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.26 | – | – |

| Median lymphocyte count (IQR)—×109 | 1.4 (1.1–1.9) | 1.2 (1.0–1.6) | 1.1 (0.9–1.2) | 0.27 | – | – |

| Median alanine aminotransferase (IQR)—U/L | 20.0 (13.0–27.9) | 23.8 (16.1–33.7) | 1.1 (1.0–1.1) | 0.001 | 1.0 (0.9–1.0) | 0.20 |

| Missing—N | 2 | 0 | 2 | – | – | – |

| Median aspartate transaminase (IQR)—U/L | 22.0 (18.5–29.5) | 28.0 (22.3–42.1) | 1.0 (0.9–1.0) | 0.07 | – | – |

| Missing—N | 2 | 0 | 2 | – | – | – |

| Median creatinine (IQR)—μmol/L | 60.0 (51.0–72.0) | 64.0 (53.0–76.4) | 1.0 (0.9–1.0) | 0.06 | – | – |

| Missing—N | 4 | 0 | 4 | – | – | – |

| Median C-reactive protein (IQR)—mg/l | 5.90 (1.82–14.5) | 14.6 (5.5–36.0) | 1.1 (1.0–1.1) | <0.001 | 1.0 (1.0–1.1) | 0.002 |

| Missing—N | 4 | 2 | 6 | – | – | – |

*For group comparison between asymptomatic/mild COVID-19 versus moderate-to-severe COVID-19 infection, logistic regression was used. Patients with missing laboratory results were omitted from the comparison.

p-values < 0.05 are marked in bold.

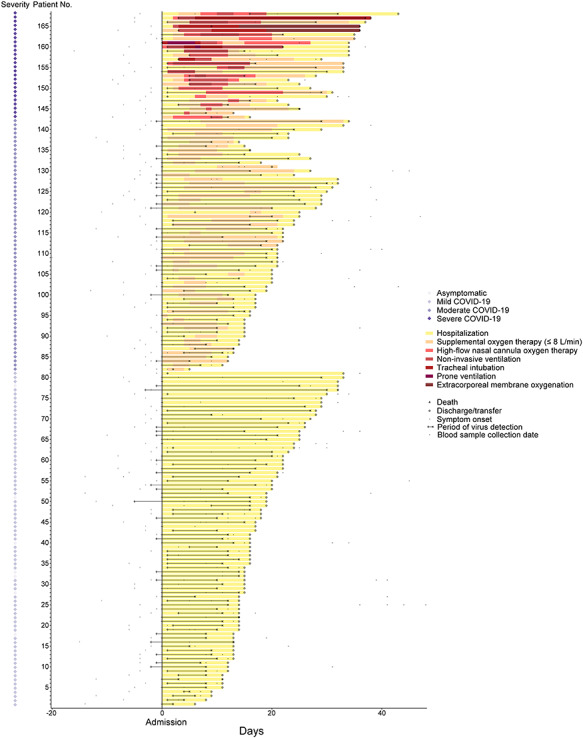

Figure 2.

Progress of and treatment provided to 168 patients with COVID-19. Day of admission was set as day 0.

Among the 168 patients in this cohort, 81 (48.2%) did not require oxygen therapy and were classified as asymptomatic or mild COVID-19, 87 (51.8%) had moderate-to-severe disease and were receiving supplemental oxygen or ventilatory support. Patients who received supplemental oxygen were older, had a higher systolic blood pressure and had a more frequent occurrence of chest pain/tightness, dyspnea and myalgia compared with those who did not. Patients with more moderate-to-severe COVID-19 also had lower white cell count and higher serum levels of alanine aminotransferase and C-reactive protein. The common symptoms at the time of hospital admission were fever (67.9%) and cough (49.4%). The median time from the onset of symptom to hospital admission was 3 days. More than one-third of the patients (36.9%) reported at least one coexisting disease. Systolic blood pressure > 124, presence of chest pain/tightness or myalgia at hospital admission, white cell count < 3 × 109 and C-reactive protein > 22 mg/l within 48 h of admission were the independent variables included for the clinical risk score calculation (Table 2). The prognostic performance of the clinical risk score was shown in Supplementary Figure S4 available online at http://bib.oxfordjournals.org/, demonstrating an area under curve of 0.74 (95% CI: 0.67–0.81), with a sensitivity of 0.71 and specificity of 0.86 at the best cut-off point (total score = 3).

Table 2.

Clinical risk score for predicting COVID-19 outcome

| Items | OR (95% CI) (multivariable) | Score |

| Systolic blood pressure > 124 | 1.9 (0.9–4.1) | 2 |

| Chest pain or tightness | 3.6 (1.1–14.5) | 4 |

| Myalgia | 2.7 (0.9–9.7) | 3 |

| White cell count < 3 ×109 | 2.2 (0.6–9.3) | 2 |

| C-reactive protein > 22 mg/l | 3.9 (1.7–9.4) | 4 |

Among the 26 patients who had severe COVID-19 infection, 16 required noninvasive ventilation, 13 received tracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation and 2 required extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Both patients required extracorporeal membrane oxygenation died subsequently. Overall, among patients with moderate-to severe COVID-19 infection, the most frequent complications were acute respiratory distress syndrome (24.1%), deranged liver function (11.5%) and nosocomial infection (3.4%). Patients who had received oxygen support had a higher complication rate than those who did not (4/81, 4.9% versus 44/87, 50.6%, P < 0.001, Fisher’s exact test). The median duration of hospital stay and time to viral clearance were longer for those patients requiring supplemental oxygen or mechanical ventilation (Table 3).

Table 3.

Clinical outcomes

| Asymptomatic or mild COVID-19 | Moderate-to-severe COVID-19 | All patients | |

| (N = 81) | (N = 87) | (N = 168) | |

| Complications—no. (%) | |||

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 0 (0.0) | 21 (24.1) | 21 (12.5) |

| Nosocomial infection | 3 (3.7) | 3 (3.4) | 6 (3.6) |

| Deranged liver function test | 1 (1.2) | 10 (11.5) | 11 (6.5) |

| Acute kidney injury | 0 (0.0) | 5 (5.7) | 5 (3.0) |

| Myocarditis | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.3) | 2 (1.2) |

| Septic shock | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.3) | 2 (1.2) |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulopathy | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (0.6) |

| Oxygen therapy—no. (%) | |||

| Supplemental oxygen therapy (≤8 L/min) | 0 (0.0) | 81 (93.1) | 81 (48.2) |

| High-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy | 0 (0.0) | 23 (26.4) | 23 (13.7) |

| Noninvasive ventilation | 0 (0.0) | 16 (18.4) | 16 (9.5) |

| Tracheal intubation | 0 (0.0) | 6 (6.9) | 6 (3.6) |

| Prone ventilation | 0 (0.0) | 5 (5.7) | 5 (3.0) |

| Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.3) | 2 (1.2) |

| Median hospital stay (IQR)—days | 16 (14–20) | 22 (16–28) | 19 (15–25) |

| Median viral positive duration (IQR)—days | 11 (9–17) | 16 (9–20) | 13 (9–19) |

| Discharge destination—no. (%) | |||

| Home | 69 (85.2) | 62 (71.3) | 131 (78.0) |

| Transfer to other hospitals for surveillance | 12 (12.8) | 23 (26.4) | 35 (20.8) |

| Death | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.3) | 2 (1.2) |

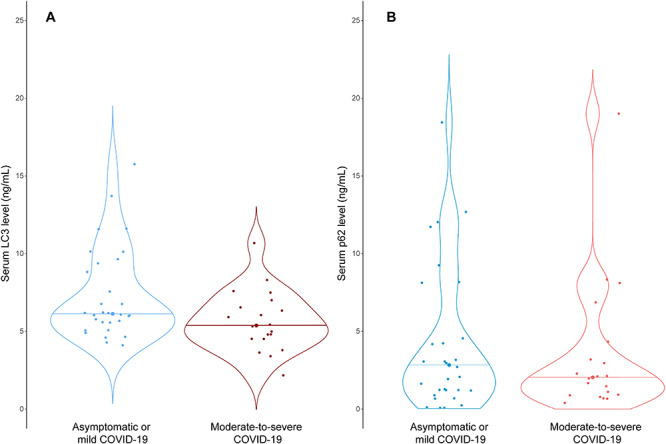

Concentrations of autophagy-/lysosome-associated biomarkers in serum samples

The change of serum LC3B and p62 concentrations over time in the entire cohort is displayed in Supplementary Figure S5 available online at http://bib.oxfordjournals.org/. A total of 50 patients (30 asymptomatic or mild cases and 20 moderate-to-severe COVID-19) had blood samples collected within 10 days of symptom onset. The baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes of this sub-group of patients are summarized in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2 available online at http://bib.oxfordjournals.org/. Serum LC3B concentrations in the moderate-to-severe group were significantly lower than that in the asymptomatic or mild COVID-19 patients (P = 0.03) (Figure 3A). There was, however, no difference in the serum p62 concentrations between the two groups (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Violin plots of s concentrations of (A) LC3B and (B) p62 in COVID-19 patients with asymptomatic or mild (N = 30) and moderate-to-severe disease (N = 20). Horizontal lines in the plots are medians. The differences among groups were compared by t-test.

Association between LC3B level, clinical risk factors and outcomes

Table 4 shows the regression models using autophagy/lysosome markers and the clinical risk score for predicting moderate-to-severe COVID-19. In the univariate model that evaluates autophagy/lysosome markers, there was an association between a decrease in the serum LC3B concentration and moderate-to-severe COVID-19. Serum LC3B concentration of 5.5 ng/ml significantly distinguished patients with asymptomatic or mild disease from those with moderate or severe COVID-19 [OR 4.02 (95% CI: 1.2–13.6), P = 0.026]. Serum p62 concentrations, however, did not predict the outcome. The prediction performance of each autophagy biomarker was shown in Supplementary Figure S6 available online at http://bib.oxfordjournals.org/. Nevertheless, in patients ≤50 years, serum concentrations of p62 in the moderate-to-severe group were significantly lower than in the asymptomatic/mild group for those aged 50 or below (P = 0.03) (Supplementary Figure S7 available online at http://bib.oxfordjournals.org/). Using the univariate model, the OR of the clinical risk score alone was 1.6 (1.1–2.2) per unit score. Patients with total score > 3 increased the risk of moderate-to-severe COVID-19 OR: 7.5 (2.0–27.9). In the multivariate model that included both serum LC3B concentration and the clinical risk score together with age and sex, a decrease in LC3B concentration <5.5 ng/ml remained as an independent predictor for moderate-to-severe COVID-19 disease.

Table 4.

Models to predict moderate-to-severe COVID-19 disease with LC3B level and clinical risk score

| Models | Asymptomatic or mild COVID-19 (N = 30) | Moderate-to-severe COVID-19 (N = 20) | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

| Autophagy/lysosome markers (univariate) | ||||

| LC3B concentration—ng/mla | 6.13 [5.58–9.24] | 5.38 [4.52–6.66] | 0.7 (0.5–0.9) | 0.044 |

| LC3B < 5.5 ng/ml—no.(%) | 7 (23.3) | 11 (55.0) | 4.0 (1.2–13.6) | 0.026 |

| p62 concentration—ng/mla | 2.40 [1.21–4.48] | 2.05 [0.93–3.48] | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.647 |

| p62 < 3.0 ng/ml—no.(%) | 17 (56.7) | 14 (70.0) | 1.8 (0.5–5.9) | 0.344 |

| Clinical risk score (univariate) | 2 [0–2] | 4 [2–5] | 1.6 (1.1–2.2) | 0.005 |

| Clinical risk score > 3 (univariate) | 5 (16.7) | 8 (40.0) | 7.5 (2.0–27.9) | 0.003 |

| LC3B level and clinical risk score as independent variables (multivariate) | ||||

| Age (OR, 95% CI) | 1.0 (0.9–1.0) | 0.151 | ||

| Male (OR, 95% CI) | 1.0 (0.2–4.5) | 0.986 | ||

| LC3 < 5.5 ng/ml (OR, 95% CI) | 4.6 (1.1–22.0) | 0.042 | ||

| Clinical risk score > 3 (OR, 95% CI) | 7.9 (1.9–41.0) | 0.007 | ||

aMedian [IQR].

p-values < 0.05 are marked in bold.

Discussion

By transcriptome analysis, we first showed that DEGs in the PBMCs isolated from COVID-19 patients were significantly enriched in cell cycle, cholesterol metabolism and the lysosome pathway. Our study revealed that most of the lysosome genes were strongly upregulated, suggesting an aberrant activation of lysosome function in PBMCs. Using clinical samples for validation, we further demonstrated that circulating level of LC3B, whose degradation is lysosome-dependent, was reduced, and such reduction was associated with important clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19. A decrease in LC3B level <5.5 ng/ml, within 10 days of the symptom onset, independently predicted the development of moderate-to-severe disease, requiring supplemental oxygen or ventilatory support.

Aside from the lysosome pathway, altered cholesterol biosynthesis and distribution are critical for the pathogenesis of viral infection by modulating viral entry and assembly as well as the type I interferon response [15]. Our transcriptome analysis revealed eight upregulated genes important for cholesterol metabolism. Voltage-dependent anion-selective channel 1 (VDAC1) and translocator protein (TSPO) are localized on the mitochondrial membrane and are involved in transporting cholesterol into the mitochondria [16, 17], whereas Lipase A (LIPA) and Niemann-Pick disease type C2 (NPC2) function in the production and egress of cholesterol from the lysosome compartment [18, 19]. Another upregulated gene, CD36, is involved in the cellular uptake of cholesterol [20]. This transcriptomic signature suggests a possible increase in the cellular uptake and utilization of cholesterol in the PBMCs during COVID-19. This finding is consistent with a recent study showing increased cholesterol consumption during SARS-CoV-2 exocytosis in the PBMCs of COVID-19 patients triggered SREBP-2 activation, which leads to cytokine storm [21]. The 5,7-conjugated diene sterol 7-dehydrocholesterol (7-DHC), which is a substrate of 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase (DHCR7) for cholesterol biogenesis, has also been shown to regulate type I interferon production upon viral infection [22]. It is therefore worthwhile to further investigate how the 7-DHC/interferon signaling is altered in relation to the cytoplasmic cholesterol level in COVID-19.

PBMCs are a diverse mixture of lymphocytes (T cells, B cells and natural killer cells) and monocytes. In this regard, activation of primary T lymphocytes has been shown to trigger the lysosome development in CD4+ and CD8+ subsets [23]. Degradation of the immune checkpoint cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) was also shown to be dependent on lysosome, whose inhibition by chloroquine resulted in the attenuation of transplant rejection [24, 25]. In addition, lysosome is fundamentally involved in the antigen and autoantigen processing in B cells [26]. Target-cell stimulation of the natural killer cells also resulted in the rapid biogenesis of lysosomes [27]. Therefore, our finding that the lysosome pathway is activated in PBMCs is consistent with the immune activation and the possible autoimmune pathogenesis of COVID-19 [28–30]. In this study, lower concentrations of LC3B, a protein degraded by lysosome, could discriminate moderate-to-severe and asymptomatic/mild COVID-19 patients. Although the exact nature of the underlying mechanisms that regulate lysosome function during COVID-19 are still being elucidated, these observations provide evidence that reduced serum LC3B level could serve as a surrogate marker of excessive PBMC activation and thus prognostication. Nevertheless, further research is needed to clarify the detailed function of lysosome in immunity/autoimmunity during COVID-19 pathogenesis.

This study has two major limitations. First, we used circulating proteins as surrogate markers of the autophagosome–lysosome system, and they may not reflect the precise magnitude of lysosome function/dysfunction in the originating tissue(s), which are presumably PBMCs. In future studies, it would be interesting to explore the associations between disease severity and the LC3B and p62 levels in PBMCs. Second, this study was conducted at a single center with few patients. A larger cohort study of patients with COVID-19 from other areas is required to validate the predictive capability of these two circulating proteins.

Conclusion

Lysosome is excessively activated in the PBMCs isolated from COVID-19 patients. Circulating LC3B (a protein degraded through lysosome) could serve as an independent prognostic biomarker for important clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19. This preliminary finding provides evidence supporting the rationale for LC3B levels to stratify COVID-19 patients so that patients with lower LC3B will require early hospital admission for potential supplemental oxygen therapy and other respiratory support.

Key Points

Transcriptome analysis revealed excessive activation of lysosome in PBMCs isolated from COVID-19 patients.

Reduced circulating levels of LC3B (a protein degraded through the lysosome pathway) were associated with moderate-to-severe COVID-19.

Circulating LC3B might serve as a prognostic marker for COVID-19.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Shisong Fang is a chief scientist at the Shenzhen Center for Disease Control and Prevention. He is an expert in emerging virus infection and is responsible for the COVID-19 screening in Shenzhen, China.

Lin Zhang is an assistant professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong and a researcher at the CUHK-Shenzhen Research Institute. Her research interests are infectious disease and autophagy. She has relevant experience in studying the autophagy mechanism in infectious diseases.

Yingzhi Liu is a PhD student at the Chinese University of Hong Kong and a researcher at the CUHK-Shenzhen Research Institute. She is currently working on the epidemiological and microbial characteristics of respiratory viral infection. She is familiar with data analysis for biomarker identification and model selection.

Wenye Xu is a PhD student at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. She has experience in serum immune biomarker assays for COVID-19 patients.

Weihua Wu is a scientist at the Shenzhen Center for Disease Control and Prevention. He is an expert in emerging virus infection and is responsible for the COVID-19 screening in Shenzhen, China.

Ziheng Huang is a research assistant at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. He has experience in bioinformatics, including transcriptome and metagenomic analysis for pneumonia patients.

Xin Wang is a scientist at the Shenzhen Center for Disease Control and Prevention. He is an expert in emerging virus infection.

Hui Liu is a scientist at the Shenzhen Center for Disease Control and Prevention. He is an expert in emerging virus infection.

Ying Sun is a scientist at the Shenzhen Center for Disease Control and Prevention. He is an expert in emerging virus infection.

Renli Zhang is the department director of Microbiology Inspection Division at the Shenzhen Center for Disease Control and Prevention. He is an expert in infection and immunity, with significant research findings on the rapid detection/diagnosis of pathogens of infectious diseases.

Bo Peng is a scientist at the Shenzhen Center for Disease Control and Prevention. He is an expert in emerging virus infection.

Xiaodong Liu is a research assistant professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. He has experience in genetic association study.

Xiao Sun is a postdoctoral fellow at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Her research interests include COVID-19 and autophagy.

Jun Yu is the director of the Research Laboratory of Institute of Digestive Disease at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. She is an expert in molecular pathogenesis and biomarkers of gastrointestinal cancers.

Francis Ka Leung Chan is the dean of the Faculty of Medicine at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Over the past decade, his works on the feasibility of screening, local cancer demographics, risk factors and screening modalities have significantly contributed to the launch of a 3-year colorectal cancer screening program.

Siew Chien Ng is the assistant dean of the Faculty of Medicine at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. She leads large-scale epidemiological and genomic research in inflammatory bowel diseases across Asia-Pacific. Her work in colorectal cancer includes screening of high-risk individuals and identification of new diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for gastrointestinal cancers.

Sunny Hei Wong is an associate professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. He has experience in studying the host genetic susceptibility to common diseases, including mycobacterial infection and inflammatory bowel diseases.

Maggie Hai Tian Wang is an assistant professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. She is a specialist in bioinformatics, statistical genetics and genetic epidemiology of infectious diseases.

Tony Gin is an emeritus professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. He is an expert in the research of perioperative complications and persistent pain after surgery.

Gavin Matthew Joynt is the chairman of the Department of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. He has outstanding work in both intensive care and infection as well as pharmacokinetics of antibiotics.

David Shu Cheong Hui is the chairman of the Department of Medicine and Therapeutics at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. His research team has a strong track record in the study of exhaled air dispersion during application of different respiratory therapies, sleep-disordered breathing and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Tiejian Feng is an associate director at the Shenzhen Center for Disease Control and Prevention. He is an expert in emerging virus infection and is responsible for the COVID-19 screening in Shenzhen, China.

William Ka Kei Wu is an associate professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong and a researcher at the CUHK-Shenzhen Research Institute. He has extensive experience in computational modeling in gene regulation and data analysis for high throughput genomic technologies.

Matthew Tak Vai Chan is a professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. His research focus is large clinical trials in anesthesia.

Xuan Zou is the secretary of the Party Committee of the Shenzhen Center for Disease Control and Prevention. His major research is about the policy reform of public health system. He is specialized in health economy.

Junjie Xia is the director of the Shenzhen Center for Disease Control and Prevention. He has led his team to reveal the risk factors of infectious diseases for prevention and treatment in China.

Contributor Information

Shisong Fang, Shenzhen Center for Disease Control and Prevention, China.

Lin Zhang, CUHK-Shenzhen Research Institute, China.

Yingzhi Liu, CUHK-Shenzhen Research Institute, China.

Wenye Xu, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

Weihua Wu, Shenzhen Center for Disease Control and Prevention, China.

Ziheng Huang, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

Xin Wang, Shenzhen Center for Disease Control and Prevention, China.

Hui Liu, Shenzhen Center for Disease Control and Prevention, China.

Ying Sun, Shenzhen Center for Disease Control and Prevention, China.

Renli Zhang, Shenzhen Center for Disease Control and Prevention, China.

Bo Peng, Shenzhen Center for Disease Control and Prevention, China.

Xiaodong Liu, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

Xiao Sun, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

Jun Yu, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

Francis Ka Leung Chan, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

Siew Chien Ng, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

Sunny Hei Wong, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

Maggie Hai Tian Wang, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

Tony Gin, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

Gavin Matthew Joynt, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

David Shu Cheong Hui, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

Tiejian Feng, Shenzhen Center for Disease Control and Prevention, China.

William Ka Kei Wu, CUHK-Shenzhen Research Institute, China.

Matthew Tak Vai Chan, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

Xuan Zou, Shenzhen Center for Disease Control and Prevention, China.

Junjie Xia, Shenzhen Center for Disease Control and Prevention, China.

Authors’ contributions

S.F., W.W., D.S.C.H., T.F., X.Z. and J.X. took care of the design of the work and paper revision; Lin Zhang, W.K.K.W. and M.T.V.C. made substantial contribution to the conception, design of the work and interpretation of data and have drafted the work or substantively revised it; Y.L. and W.X. took care of the design of the work, the acquisition and analysis; X.W., H.L., Y.S., R.Z., B.P. took care of the design of the work; X.L., X.S. and M.H.T.W. took care of the acquisition and analysis; J.Y., F.K.L.C., S.C.N., S.H.W., T.G. and G.M.J. took care of manuscript revision.

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China (81873560, 82070576, 81871631); Shenzhen Science and Technology Programme, Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Commission (JCYJ20180307102005105, JCYJ20180307150626228, JCYJ20180508161604382); Shenzhen bay laboratory grant (2020B1111340078).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the ethics committee and the requirement for informed consent was waived by the Shenzhen Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

Consent for publication

All the authors are aware of and agree to the content of the paper, copyright assignment and authorship responsibility.

Availability of data and materials

Research data will be shared upon request.

References

- 1. Hu W, Chan H, Lu L, et al. Autophagy in intracellular bacterial infection. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2020;101:41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Docherty AB, Harrison EM, Green CA, et al. Features of 20 133 UK patients in hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ 2020;m1985:369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yang N, Shen HM. Targeting the endocytic pathway and autophagy process as a novel therapeutic strategy in COVID-19. Int J Biol Sci 2020;16(10):1724–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Choi Y, Bowman JW, Jung JU. Autophagy during viral infection—a double-edged sword. Nat Rev Microbiol 2018;16(6):341–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cottam EM, Whelband MC, Wileman T. Coronavirus NSP6 restricts autophagosome expansion. Autophagy 2014;10(8):1426–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shi CS, Nabar NR, Huang NN, et al. SARS-Coronavirus Open Reading Frame-8b triggers intracellular stress pathways and activates NLRP3 inflammasomes. Cell Death Dis 2019;5:101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yue Y, Nabar NR, Shi CS, et al. SARS-Coronavirus Open Reading Frame-3a drives multimodal necrotic cell death. Cell Death Dis 2018;9(9):904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, Levine B. Methods in mammalian autophagy research. Cell 2010;140(3):313–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. WHO . Laboratory Testing for Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) in Suspected Human Cases: Interim Guidance. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331501 (19 March 2020, date last accessed). License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- 10. Bi Q, Wu Y, Mei S, et al. Epidemiology and transmission of COVID-19 in 391 cases and 1286 of their close contacts in Shenzhen, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(8):911–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang X, Zhang X, Chu ESH, et al. Defective lysosomal clearance of autophagosomes and its clinical implications in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. FASEB J 2018;32(1):37–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gandhi RT, Lynch JB, Del Rio C. Mild or moderate Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(18):1757–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. An official clinical practice guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019;200(7):e45–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schisterman EF, Perkins NJ, Liu A, et al. Optimal cut-point and its corresponding Youden Index to discriminate individuals using pooled blood samples. Epidemiology 2005;16(1):73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Osuna-Ramos J, Reyes-Ruiz J, del Ángel R. The role of host cholesterol during flavivirus infection. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2018;8:388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Weiser BP, Salari R, Eckenhoff RG, et al. Computational investigation of cholesterol binding sites on mitochondrial VDAC. J Phys Chem B 2014;118(33):9852–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jaipuria G, Leonov A, Giller K, et al. Cholesterol-mediated allosteric regulation of the mitochondrial translocator protein structure. Nat Commun 2017;8:14893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Li F, Zhang H. Lysosomal acid lipase in lipid metabolism and beyond. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2019;39(5):850–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McCauliff LA, Langan A, Li R, et al. Intracellular cholesterol trafficking is dependent upon NPC2 interaction with lysobisphosphatidic acid. Elife 2019;8:e50832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Podrez EA, Febbraio M, Sheibani N, et al. Macrophage scavenger receptor CD36 is the major receptor for LDL modified by monocyte-generated reactive nitrogen species. J Clin Invest 2000;105(8):1095–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee W, Ahn JH, Park HH, et al. COVID-19-activated SREBP2 disturbs cholesterol biosynthesis and leads to cytokine storm. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2020;5(1):186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Xiao J, Li W, Zheng X, et al. Targeting 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase integrates cholesterol metabolism and IRF3 activation to eliminate infection. Immunity 2020;52(1):109–22.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shen DT, Ma JSY, Mather J, et al. Activation of primary T lymphocytes results in lysosome development and polarized granule exocytosis in CD4+ and CD8+ subsets, whereas expression of lytic molecules confers cytotoxicity to CD8+ T cells. J Leukoc Biol 2006;80(4):827–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Iida T, Ohno H, Nakaseko C, et al. Regulation of cell surface expression of CTLA-4 by secretion of CTLA-4-containing lysosomes upon activation of CD4+T cells. J Immunol 2000;165(9):5062–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cui J, Yu J, Xu H, et al. Autophagy-lysosome inhibitor chloroquine prevents CTLA-4 degradation of T cells and attenuates acute rejection in murine skin and heart transplantation. Theranostics 2020;10(18):8051–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Burster T, Beck A, Tolosa E, et al. Cathepsin G, and not the asparagine-specific endoprotease, controls the processing of myelin basic protein in lysosomes from human B lymphocytes. J Immunol 2004;172(9):5495–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liu D, Xu L, Yang F, et al. Rapid biogenesis and sensitization of secretory lysosomes in NK cells mediated by target-cell recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2004;102(1):123–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ehrenfeld M, Tincani A, Andreoli L, et al. Covid-19 and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev 2020;19(8):102597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Woodruff MC, Ramonell RP, Nguyen DC, et al. Extrafollicular B cell responses correlate with neutralizing antibodies and morbidity in COVID-19. Nat Immunol 2020;21(12):1506–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Galeotti C, Bayry J. Autoimmune and inflammatory diseases following COVID-19. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2020;16(8):413–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Research data will be shared upon request.