Obesity

Surgery,

5, 61-64

Gastric Banding for Treatment

Preliminary

Results

G. Bajardi;

M. Florena

G. Ricevuto;

G. Mastrandrea;

of Morbid

G. Pischedda;

Obesity:

D. Valenti;

G. Rubino;

Departmenf of Surgical and Anatomical Sciences,Division of General and Vascular Surgery, University of

Palermo, Palermo, Italy

Background:

gastric

banding

(GB)

has been

used

for

treatment

of morbid

obesity.

Methods:

a banding

device,

introduced

by Broadbent

and consisting

of a self-blocking

nylon

strip covered

with a silicone

tube, was used in 13

patients

who

have

completed

l-year

follow-up.

This

device

was used for its mechanical

properties,

biocompatibility,

ease of insertion

and low cost. Results:

at 1 year,

mean

excess

weight

loss was 51.6%,

with all but one

patient

losing

more than 25% of excess

weight.

Associated illnesses

resolved.

There

were

two complications

(15%):

one

patient

required

band

removal

for selfinduced

vomiting

and

one patient

required

repair

of

an incisional

hernia.

Conclusions:

GB has had good

results

thus far. Reported

differences

depend

on materials,

stoma

diameter,

pouch

size,

and

developing

techniques.

Key

words:

surgery

Morbid

obesity,

gastric

banding,

bariatric

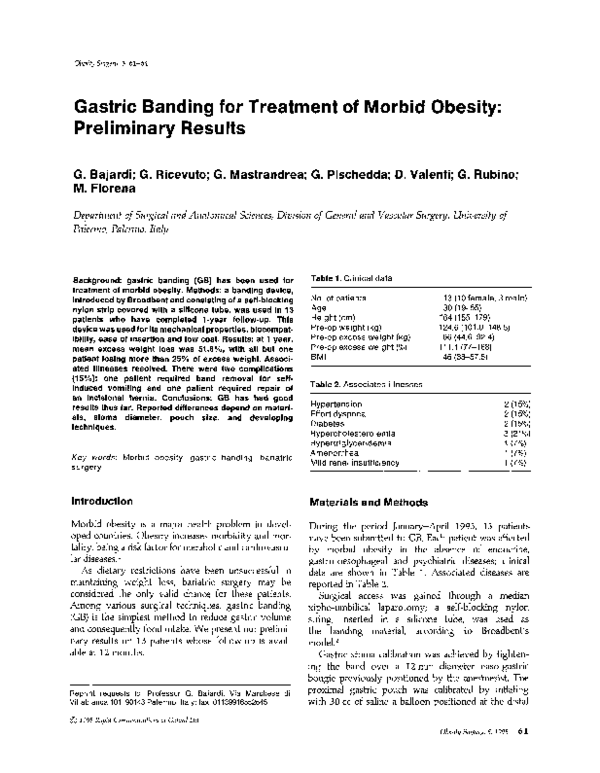

Table

1. Clinical

No. of patients

Age

Height

(cm)

Pre-op

weight

Pre-op

excess

Pre-op

excess

BMI

Table

data

(kg)

weight

weight

2. Associated

(kg)

(%)

13 (10 female,

30 (19-55)

164 (155-179)

124.6 (lOl.rS148.5)

66 (44.8-92.4)

111.1 (77-168)

46 (38-57.5)

3 male)

illnesses

Hypertension

Effort dyspnea

Diabetes

Hypercholesterolemia

Hypertriglyceridemia

Amenorrhea

Mild renal insufficiency

2

2

2

3

1

1

1

(15%)

(15%)

(15%)

(21%)

(7%)

(7%)

(7%)

Introduction

Materials

Morbid obesity is a major health problem in developed countries. Obesity increasesmorbidity and mortality, being a risk factor for metabolic and cardiovascular diseases.l

As dietary restrictions have been unsuccessful in

maintaining weight loss, bariatric surgery may be

considered the only valid chance for these patients.

Among various surgical techniques, gastric banding

(GB) is the simplest method to reduce gastric volume

and consequently food intake. We present our preliminary results on 13 patients whose follow-up is available at 12 months.

During the period January-April 1993, 13 patients

have been submitted to GB. Each patient was affected

by morbid obesity in the absence of endocrine,

gastro-oesophageal and psychiatric diseases;clinical

data are shown in Table 1. Associated diseasesare

reported in Table 2.

Surgical access was gained through a median

xipho-umbilical laparotomy; a self-blocking nylon

string, inserted in a silicone. tube, was used as

the banding material, according to Broadbent’s

model.2

Gastric stoma calibration was achieved by tightening the band over a 12 mm diameter naso-gastric

bougie previously positioned by the anesthesist.The

proximal gastric pouch was calibrated by inflating

with 30 cc of saline a balloon positioned at the distal

Reprint

requests

to: Professor

Villabianca

101, 90143 Palermo,

0

1995 Rapid

Communications

G. Bajardi,

Via Marchese

Italy; fax: 01139916552645

of Oxford

di

and Methods

Ltd

Obesity Surgery, 5, 1995

61

�B~jmdi

et al.

Table

3. Weight

loss

after

GB

EW (kg)

At surgery

1st p.o. month

6th p.o. month

12th p.o. month

63.3

53.3

40.6

31.1

EWL

(%)

17.0

36.8

51.6

WL (kg)

BMI

11.0

23.7

33.2

46.0

42.5

37.4

34.3

EW = excess

weight;

EWL = excess

weight

loss:

loss; BMI = body mass index;

p.o. = post-operative.

Table

4. Weight

loss - literature

EWL

= excess

weight

= weight

results

EWL

Favretti

et ZI/.‘~

Kuzmak”

Forsell

et a/.’

Lovig et a/.’

Lovig et al.7

Kirby et a1.9

WL

56

80

5.5

74

38

54

(%)

Follow-up

12

10

12

12

60

12

months

months

months

months

months

months

follow-up. A functional gastric stoma stenosis at the

seventh post-operative

month caused band removal

(7%); this patient used self-induced vomiting during

the early post-operative

period. After band removal,

no other bariatric surgery attempt was made on this

patient as weight loss achieved was judged satisfactory by herself, and she is being followed. We observed an incisional hernia (7%) at the fourth postoperative month, which was successfully repaired.

No vitamin or other nutrient deficiency has been

registered during the follow-up period. Hemoglobin,

iron, electrolites and proteins were in normal range at

the scheduled samples. The pre-operative

elevated

levels of cholesterol, triglycerides

and blood sugar

always corrected after surgery. In a patient who had

longstanding

amenorrhea pre-operatively,

a normal

ovulatory cycle restarted after the second post-operative month.

loss

Discussion

end of the bougie, immediately below the cardia and

proximal to the band.

Antithrombotic

prophylaxis

was accomplished in

each patient using intra and post-operative

lower

limbs elastic bandage, and early post-operative mobilization. On the third post-operative

day a barium

swallow was given to view gastric pouch emptying

and gastric stoma patency. On the fourth post-operative day a low calory liquid diet was started (50 cc

per day). From the seventh post-operative

day until

the sixth week, a semi-solid diet was advised, and

patients were invited to self-regulate the amount of

food intake according to the sensation of satiety.

After the sixth post-operative

week, a free diet was

allowed.

Results

No early morbidity or mortality occurred. Each patient

was seen at the first, third, sixth and 12th post-operative month.

As shown on Table 3, the highest weight loss was

achieved during the first 6 months; in this period

mean weight loss was 23.7 kg, corresponding

to

36.8% of pre-operative

excess weight. During the

second 6-month period, weight loss has been slower

with tendency to stabilization. At the end of 1 year,

mean weight loss was 32.2 kg, equal to 51.6% of

mean pre-operative excess weight. In only one patient,

weight loss (25% of pre-operative excess weight) was

judged unsatisfactory.

No major late complications were found during

62

Obesity

surgery,

5, 199s

Since its early proposal by Molina3 and K011,~ GB

appeared to be a simple and safe technique, able to

induce a sensible weight loss in morbidly obese patients. Minimal surgical trauma, as well as maintenance

of gastro-enteric

integrity, made this technique fully

reversible. These characteristics led us to use GB as

an alternative to biliopancreatic

diversion

(BPD),

which we had performed since 1990.~

Our preliminary results show at 12 months an

excess weight loss of 51.6%,

with a residual obesity

expressed by a mean BMI of 34.3; these findings are

similar to those reported by others (Table 4). Unfortunately, these data are difficult to compare because of

lack of standardization

of some key steps in this

technique such as gastric pouch and stoma calibration.

Some authors have stressed the high percentage of

complications and revisions.g,ll This may be due to

variability in this technique regarding some markpoints like banding material, stoma diameter, gastric

pouch volume, and whether the whole system will

keep the configuration imposed by the surgeon during

the implant.

We had a late complication rate of 15%; for both of

these patients surgery was necessary, to remove a

band in one and repair an incisional hernia in the

other. More serious complications,

however,

have

been experienced by other workers.

Among nonspecific reported complications, wound

infections (5.7%) and incisional hernias (8.6-10%)

are

the commonest, followed by deep vein thrombosis

(DVT) (1.7%) and p u 1monary complications (Table 5).

Among specific complications, the most frequently

�Gastric

Table

5. Non-specific

Favretti

Kuzmak

Sjoberg

Lovig et

Table

et a/.13

et a/.“’

et a1.6

al.7

6. Specific

Favretti

Kuzmak

Sjoberg

Lovig et

Granstrom

complications

eta/.13

et aI.”

et a/.6

a/.’

et al.”

4.6%

5.3%

17.0%

18.3%

complications

Early

Late

3.4%

2.7%

5.4%

3.6%

4.1%

12.7%

10.6%

13.6%

25.9%

29.1%

Re-operations

22.6%

9.2%

20.0%

14.9%

31.9%

reported are stoma1 stenosis (with or without pouch

dilatation), pouch perforation and band erosion into

the gastric wall (Table 6); these complications determine a reintervention rate of lo-ZO%, with mortality

almost absent.6,7Insufficient weight loss (7% in our

experience) represents another reason for therapeutic

failure.

The optimal stoma diameter is considered to be

12 min;2,7,9KuzmaklO suggestsa wider stoma (13 mm)

for patients below 146 kg. Smaller diameters (11 mm)

have been reported as a cause of persistent vomiting

in 2% of patients submitted to GB.”

Granstrom,” using a Marlex mesh band, observed

16 stenoses(22%), occurring in patients whose stomas

were calibrated with 11 or 12 mm bougies. The diameter of gastric stoma is not the only determinant of

stenosis: stomas patent to a pediatric gastroscope

have been observed in patients clinically showing

persistent vomiting and excessive weight 10~s.~’Excessive food intake may lead to gastric pouch dilatation

far beyond the intraoperatively determined measure,

resulting in a stoma size insufficient for proper pouch

emptying, and responsible for a ‘functional’ stenosis.

Other complications, such as band kinking or erosion

into the stomach wall, have been correlated with the

materials employed. Marlex mesh, Dacron or PTFE

have all been considered responsible for a fibrotic

reaction by the surrounding tissuesor erosions of the

gastric wall. ‘,I1 Pouch perforation with tissue materials, although rare (1.3%), is associated with a high

morta1ity.r’

The major advantage of Broadbent’s system,’

beyond its very low cost, derives from the coupling

of the nylon string stiffness and the silicone coveringtube biocompatibility. These characteristics seem to

prove effective in preventing band dilatation, slippage

or erosion into the gastric wall.

Gastric pouch volume is the other important deter-

Banding

minant of success.Optimal volumes have variously

been reported between 30 rnll’ and 50 m1;gin another

seriesthe banding device has been passedbehind the

stomach using anatomical landmarks for band position,

like the short gastric vessels7’1’or the standard distance of 3 cm below the cardia.s Keeping correct

pouch dimensions is very important, because pouch

dilatation has been correlated with minimal weight

loss and with weight gain observed after prolonged

follow-up; 7,gfurthermore, a large gastric pouch can be

considered responsible of a functional stenosis. We

believe that pouch dimensioning is more precise using

the inflated balloon technique.

Full co-operation is required by the patient to

achieve clinically satisfying results. The patient must

be advised not to provoke vomiting, to take just

enough food to reach satiety, and not to drink highcalorie beverages. Inability to cope with these simple

recommendations must be considered a contraindication to this surgery, as results may be impaired and

severe complications may ensue.

Recently BroadbenP proposed laparoscopic positioning of his banding device. This appears to be a

very important step in preventing morbidity related

to the abdominal wall opening like incisional hernias,

a complication constantly present in every bariatric

surgery experience.

Usually, GB does not result in syndromes related

to vitamins, electrolytes and basic nutrients, but rare

reports of these complications can be found in the

literature.7 From this point of view, GB is much more

reliable than other bariatric surgery techniques, like

the BPD which we used in the past.5 However, we

await longterm weight loss results. Beneficial effects

in lowering cardiovascular risk factors have been

observed.

Conclusions

GB is effective in weight loss in morbidly obese

patients. Among the bariatric operations, it is the least

invasive, is reversible and lacks GI tract opening.

Laparoscopic positioning of the banding device will

be a further strong reason to select this technique for

surgical treatment of obesity. It is imperative that

standardization of measuresand materials is achieved

to compare different series in order to improve the

results. Patient selection is a critical step, as most

unsatisfactory results may be related to incapacity to

follow dietary recommendations.

Obesity Sqery,

5,

19%

63

�et al.

Bajardi

References

1. Drenick EJ, Bale GS, Seltzer F, et al. Excessive mortality

and causes of death in morbidly obese men. ]A&&4

1980;

243:

2. Broadbent

Surg

443-S.

R. A simple band for gastric banding. Obesity

1993;3:307-8.

Molina M,. Oria HE. Gastric banding. Program 6th

Bariatric Surgery Colloquium. Iowa City 1983, p. 15.

4. Kolle K. Gastric Banding, O.M.G.I. 7th Congress, Stockholm 1982, abstract 185, p. 37.

5. Bajardi G, Latteri AM, Ricevuto G, et al. Biliopancreatic

diversion: early complications.

Obesity Surg 1992; 2:

3.

177-80.

6. Sjoberg EJ, Andersen E, Hoe1 R, et al. Gastric banding

in the treatment of morbid obesity. Acta Chir Stand

1989;155:31-4.

7.

Lovig T, Hafner JFW, Kaaresen R, et al. Gastric banding

for morbid obesity: 5 years follow-up. Int J Obes 1993;

17: 453-7.

64

Obesity

8. Forsell P, Hallberg D, Hellers G. Gastric banding for

morbid obesity: initial experience with a new adjustable

band. Obesity Surg 1993; 3: 369-74.

9. Kirby RM, Ismail T, Crowson M, et al. Gastric banding

in the treatment of morbid obesity. Br ] Surg 1989; 76:

surgery,s, 1995

490-L

Kuzmak LI. Gastric banding. In: Deitel M, ed. Surgey

for the Morbidly Obese Patient. Philadelphia:

Lea and

Febiger, 1989,225-60.

11. Granstrom L, Backman L. Technical complication and

related reoperation

after gastric banding. Acta Ckir

Stand 1987;153:215-20.

12. Broadbent R, Tracey M, Harrington

P. Laparoscopic

gastric banding. A preliminary

report. Obesity Surg

10.

1993;

3: 63-7.

13. Favretti F, Enzi G, Pizzirani E, et al. Adjustable silicone

gastric banding (ASGB): the Italian experience. Obesity

Surg 1993;3:

53-6.

(Received 4 August

1994; accepted 15 November 19%).

�

giuseppe pischedda

giuseppe pischedda