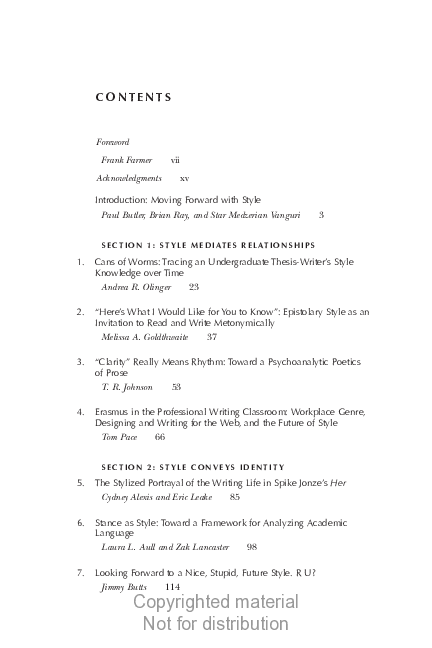

CONTENTS

Foreword

Frank Farmer

Acknowledgments

vii

xv

Introduction: Moving Forward with Style

Paul Butler, Brian Ray, and Star Medzerian Vanguri

3

S E C T I O N 1 : S T Y L E M E D I AT E S R E L AT I O N S H I P S

1.

Cans of Worms: Tracing an Undergraduate Thesis-Writer’s Style

Knowledge over Time

Andrea R. Olinger

23

2.

“Here’s What I Would Like for You to Know”: Epistolary Style as an

Invitation to Read and Write Metonymically

Melissa A. Goldthwaite

37

3.

“Clarity” Really Means Rhythm: Toward a Psychoanalytic Poetics

of Prose

T. R. Johnson

53

4.

Erasmus in the Professional Writing Classroom: Workplace Genre,

Designing and Writing for the Web, and the Future of Style

Tom Pace

66

SECTION 2: STYLE CONVEYS IDENTITY

5.

The Stylized Portrayal of the Writing Life in Spike Jonze’s Her

Cydney Alexis and Eric Leake

85

6.

Stance as Style: Toward a Framework for Analyzing Academic

Language

Laura L. Aull and Zak Lancaster

98

7.

Looking Forward to a Nice, Stupid, Future Style. R U?

Jimmy Butts

114

Copyrighted material

Not for distribution

�vi

CoNTENTS

8.

Metaphorical Translingualisms: The Hip-Hop Cipher as

Stylistic Concept

Eric A. House

133

S E C T I O N 3 : S T Y L E F O R M S S T R AT E G Y

9.

Expectations of Exaltation: Formal Sublimity as a Prolegomenon

to Style’s Unbounded Future

Jarron Slater

147

10. Civil Style: Reexamining Discourse and Rhetorical Listening in

Composition

Laura L. Aull

160

11. Applied Legal Storytelling: Toward a Stylistics of Embodiment

Almas Khan

173

12. What Style Can Add to Genre: Suggestions for Applying Stylistics

to Disciplinary Writing

Anthony Box

185

S E C T I O N 4 : S T Y L E C R E AT E S A N D T R A N S C E N D S

B O U N DA R I E S

13. Point of Departures: Composition and Creative Writing Studies’

Shared Stylistic Values

Jon Udelson

199

14. The Danger of Using Style to Determine Authorship: The Case of

Luke and Acts

Mike Duncan

213

15. Words, Words, Words, or Leveraging Lexis for a Pedagogy of Style

William T. FitzGerald

227

About the Authors

Index

247

245

Copyrighted material

Not for distribution

�Introduction

M OV I N G F O RWA R D W I T H S T Y L E

Paul Butler, Brian Ray, and Star Medzerian Vanguri

New uses of language often emerge at critical moments in history.

While it is possible to examine many such moments (e.g., recessions, migrant caravans, mass shootings), the phenomenon seems

especially powerful during natural disasters, when language change

accompanies physical change, uniting the material and discursive. For

example, in a blog about Hurricane Katrina, which forever changed

the city of New Orleans, Dave Zirin (2007) writes, “To the people

I spoke with, Katrina is a noun, an adjective and even a verb.” Kat

Bergeron (2006) lists such new terms as “Katrina patina” (“the visible

coating the storm left on people and things”) and “shud” (“the mucky

substance deposited by Katrina, a cross between mud and sh--”) in her

article “SLABBED! And Other Katrinaed Words; Katrina Patina.” In its

aftermath, writes Zirin, the cyclone became “something ephemeral, a

sadness seeped into the humidity. It gets into your clothes, your eyes,

your hair.”

Zirin’s post and Bergeron’s article suggest that the most dynamic

aspect of language is its ability not only to respond to but also to adumbrate and, indeed, catalyze, change. In Style and the Future of Composition

Studies, we contend the principal way that language and social change

emerges is through style. While Zirin and Bergeron show how style transformed “Katrina” from a noun to an adjective and verb, coined new

phrases, and personified the storm in unusual ways, our claim is that

style is further capable of anticipating and enabling innovative ideas,

voices, identities, and rhetorics. This is our position as editors, and,

more broadly, it is a recurring theme in this volume, in which authors

reimagine or invent such concepts as eavesdropping (Goldthwaite), trespass (Udelson), inscrutability and a “translingual style” (House), unconscious rhythm (Johnson), “possible selves” (Alexis and Leake), sublime

transdisciplinarity (Slater), and “diplomatic evidentiality” (Aull), among

others, to demonstrate how style effects change.

Copyrighted material

Not for distribution

DoI: 10.7330/9781646420117.c000b

�4

PA U L B U T L E R , B R I A N R AY, A N D S TA R M E D Z E R I A N VA N G U R I

As a canon of rhetoric, style has always possessed an adaptive or protean quality that allows writers to shape their messages for particular

purposes, audiences, and occasions. Indeed, style serves as a rich palette

of choices, enabling writers to mix, match, blend, and combine language and other semiotic forms in ways that allow surprising meanings

and possibilities to emerge. The view of style as inventive, as opposed to

static or fixed, lies at the heart of work by scholars like M.A.K. Halliday,

Mary Bucholtz, Elinor Ochs, Conrad Biber, Zak Lancaster, Laura Aull,

and Andrea Olinger (this volume). As John Vance (2014, 140), drawing

on Halliday, writes, “Languages are dynamic, open systems whose forms

(to the extent that they are ‘formal’ at all) are contingent on a vast

array of local, emergent, ‘bottom-up,’ functional language practices.”

The same position undergirds the translingual approach to writing

(see Horner et al. 2011; Canagarajah 2013; House, this volume). This

dynamic, experimental quality of style reverberates throughout our collection, challenging all of us, as readers and writers, to rethink the ways

style reads and writes us as a force of disciplinary action and change, and

situating style as a crucible in the future of the discipline—its conversations, engagements, and areas of inquiry.

A great deal has changed in the last decade since Susan Peck

MacDonald published “The Erasure of Language” (2007), in which

she describes the dissociation of sociolinguistics from composition and

subsequent decline of attention to sentence-level issues in writing. Like

Robert Connors (2000), MacDonald poignantly articulates the impact of

language and style’s erasure from the discipline—especially on students.

In fact, the past several years have seen the very resurgence of style that

scholars such as Tom Pace and Paul Butler have anticipated. Articles on

style and language have begun appearing in journals again. Books such

as The Centrality of Style (Duncan and Vanguri 2013), Style: An Introduction

(Ray 2014), and Performing Prose (Holcomb and Killingsworth 2010) have

helped to restore the idea of style as a facilitator of agency and creativity.

These recent works have built on foundational texts by Butler, Johnson

and Pace, and Lanham. They have also gone well beyond simply lamenting

the absence of style from disciplinary conversations and have articulated

what style has to offer composition, as well as how new orientations to

writing and rhetoric prompt a reconception of style itself. In other words,

we have made a central pivot from defending style’s place in research

and teaching toward exploring it from more diverse perspectives and

identifying its latent presence in contemporary scholarship—including

discourse analysis, sociolinguistics, language difference, and digital

rhetorics. Researchers on style have just begun to articulate the points

Copyrighted material

Not for distribution

�Introduction: Moving Forward with Style

5

of connection between our work and these current trends in the field.

These new fusions hold a great deal of promise for the study of style, but

also for the discipline in general, as they enable unexpected approaches

to writing instruction that value and embrace discursive contingency and

dexterity. We are now in the process of repurposing style so that it can

contribute to the writing instruction designed for the twenty-first century,

an era characterized by media convergence, rapid genre evolution, and

accelerated globalization. Our shared goals run deep, in that we need to

prepare students to be able to compose in a range of settings and circumstances and to adapt to evolving discursive environments.

How does the book reflect the many ways an inventive style forces us to

recalibrate how we write, read, and, indeed, think about language and

meaning in the twenty-first century? The following sections lay out some

of the capabilities of style by identifying key actions it performs. These

categories could easily be combined or rearranged to reveal even more

possibilities, as they merge, blend, overlap, move, and situate themselves

in the interest of stylistic virtuosity and transformation.

S T Y L E M E D I AT E S R E L AT I O N S H I P S

The future of style in composition studies anticipates style as a vehicle

for different and diverse voices to emerge—rhetorically, from exigence,

audience, occasion, context. One major focus in research on style

involves shifting relationships between rhetors and audiences. Until

recently, work on style has prioritized writers and the development of

their voices—without a full consideration of the role readers play or

how style is co-constructed. In her Rhetoric Review piece, “A Sociocultural

Approach to Style,” Andrea Olinger offers a dynamic definition and

theory of style to frame future studies, one that moves beyond a relationship in which “writers engineer style, and the readers, universally,

understand the writers’ intent” (2016, 124). Olinger draws on research

in sociocultural linguistics in order to present a model of style recognizing it as always emerging rather than static and fixed. Her full definition

describes style as the “dynamic co-construction of typified indexical

meanings (types of people, practices, situations, texts) perceived in

a single sign or a cluster of signs and influenced by participants’ language ideologies” (125). This definition demonstrates style’s function

as mediator, in that style refers not just to the writers’ choices but the

readers’ as well, and the meanings they create together. For Olinger, and

other authors in this collection, style is always in flux as it negotiates the

multiple value systems at play between language users.

Copyrighted material

Not for distribution

�6

PA U L B U T L E R , B R I A N R AY, A N D S TA R M E D Z E R I A N VA N G U R I

The works in this collection share a vision of style as dynamic, shared,

co-constructed, emergent, and performed. This model holds a great

deal of explanatory power. We can use style not just to inform how we

teach students to write well but also as an analytical tool to investigate

the language, discourse, and semiotic practices of writers and speakers

in a range of contexts, with an emphasis on their relationships with audiences. Specifically, several contributions to this collection offer conceptions of how style mediates relationships between writers and audiences.

Andrea Olinger’s chapter in this volume, “Cans of Worms,” brings

style into dialogue with research on transfer as a way of furthering

her project of defining style as co-constructed and dynamic. This

piece follows a college student named Corinne, whose understanding

of her writing style and that of her advisers adapts as she negotiates

their expectations—as well as their performances of style in their own

publications. As Olinger shows, “styles may be composed of signs with

conflicting or heterogenous indexical meanings,” for example, in a

short sentence seen by different readers as both “to the point” but also

“flowery” if it employs a metaphor (chapter 1). This ethnographic study

demonstrates how writers do in fact change their perceptions and practice of styles over time in response to interactions with audiences and

also transfer styles across their writing situations and contexts. Readers

might see the same stylistic traits differently, use different language to

describe those traits, and even contradict themselves and each other

when expressing their own perceptions and expectations about style.

Like Olinger, Ellen Carillo (2010, 2014) extends style beyond writers’ choices; for Carillo, though, style serves as a way to reinvigorate

the importance of reading in composition studies and its connection to

writing. For both Carillo and Olinger, style serves as a way to reintegrate

reading and writing after a period of their separation, most likely caught

in the divide between literary and composition studies. We argue that

style unites the process of reading and writing by making the two interactive, a kind of antiphonal effect in which the reader recalibrates the

writer and the writer stands in the shoes of, or in the place of, the reader,

in an act of rhetorical collaboration.

In “Here’s What I Would Like for You to Know” (chapter 2), Melissa

Goldthwaite continues the same idea in this volume, stating the important role of eavesdropping in epistolary writing, with the reader occupying the role of eavesdropper: “Readers are always, often unconsciously,

negotiating their identifications and disidentifications—the ways they are

or are not the intended audience for a piece of writing. Epistolary writing, however, makes that negotiation more explicit, encouraging readers

Copyrighted material

Not for distribution

�Introduction: Moving Forward with Style

7

either to identify with the audience being invoked or to consciously

inhabit the role of eavesdropper.” Goldthwaite sees this negotiable process at work in Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me. She writes:

Because the book is addressed to Coates’ 15-year-old son, readers can

eavesdrop—perhaps listening with empathy, understanding the love that

prompts this father to communicate honestly with his child about the

injustices that all Americans should face but that some have no choice but to

face because of the bodies they inhabit.

T. R. Johnson’s chapter in this volume, “‘Clarity’ Really Means

Rhythm,” also emphasizes the relationship between writers and audiences and its implications for style. Addressing the conventional notion

of clarity, Johnson reintroduces the concept of rhythm as helping to

sustain a successful dynamic between readers and authors. As he argues,

“we all know that what is meant by clarity is . . . a successful authoraudience relationship,” and “the key to this relationship can be captured

in one word: rhythm” (chapter 3). Attention to patterns and cadences

in writing that reflect elements of spoken discourse can help writers,

including college students, craft discourse that generates, inflects, and

sustains meaning by syncing with a reader’s own expectations for repetition of sounds and units of language. Examples include emphasis, flow,

alliteration, and parallelism, oral elements we generally neglect in many

genres of writing.

Tom Pace’s chapter, “Erasmus in the Professional Writing Classroom,”

offers a pedagogical approach that introduces students to the relationship between writers and readers, as mediated by genre and stylistic conventions. As Pace argues, “adhering to traditional textbook-based stylistic

exercises in the professional writing classroom often does not prepare

these students for what employers require of them in the workplace”

(chapter 4). Instead, Pace’s students, in an upper-level professional

writing course, complete a number of genre-based projects ranging

from memos and grant proposals to websites for local companies. The

course provides scaffolding for each project that prompts students to

pay attention to stylistic affordances and expectations. He states that in

asking students to learn various stylistic strategies for workplace genres

and to practice writing them in the classroom, they can then adapt these

strategies to numerous rhetorical situations: “The assignments and their

attention to style challenge students’ preconceived conceptions of style

and teach them numerous strategies for adapting these stylistic elements

to both workplace and academic settings.”

Indeed, for Pace, “teaching students various stylistic strategies for

addressing workplace genres allows students to become better equipped

Copyrighted material

Not for distribution

�8

PA U L B U T L E R , B R I A N R AY, A N D S TA R M E D Z E R I A N VA N G U R I

to write for various audiences and purposes.” This chapter represents our

broader goal to move even further beyond the commonplace perception

of style as simply correctness or adherence to rules, a view that many of

Pace’s students admit to holding at the beginning of the semester. The

key goal for any college writing course, and perhaps especially upper-level

courses in professional and technical writing, lies in helping students

understand that style involves choices and active decision-making, as well

as negotiations with readers and generic expectations. Pace shows the

ways in which his students are effectively border crossers when it comes to

writing in the disciplines and using style as the means by which they slip

in and out of different territory in writing across curricular differences.

STYLE CONVEYS IDENTITY

Every time we write or speak, we define and redefine our identity

through style. Michel Foucault (1994) explains an author’s different

identities as, for instance, the voice he or she uses in a narrative account

versus the voice in the preface of a text. In each case, different “selves”

are required. Foucault later says in an interview that identity is based on

differentiation, creation, and innovation. The future of style in composition studies is tied to ever-changing identities and the way these identities are represented or performed stylistically. Style, we assert, can be

seen as a common denominator for identity, constantly in a process of

adaptation and reinvention.

These characteristics of stylistic identity are at the heart of T. R.

Johnson’s argument about rediscovering the oral rhythms within our

unconscious minds. Arguing for a link between training in style, athletics, and musical training in Greece, Johnson probes something deep

within the unconscious that brings about the same type of identity performance normally tied to innovation, transformation, and change. For

Johnson, this fusion of identity and style, based on unconscious rhythms,

is closely linked to writing:

Given the deep roots of what we might today call a style-based pedagogy

in the athletic and musical training of the ancient Greeks, the way the

old oralist rhythms still haunt our most thrilling experiences of texts, one

can’t help but suppose that this territory is still with us at the level of the

unconscious. In ways we only dimly understand, it continues to flash into

view from time to time in contemporary discussions about how people

should learn how to write.

Similarly, Cydney Alexis and Eric Leake (chapter 5) invoke theories

of “possible selves” (imagining oneself in a role or occupation correlates

Copyrighted material

Not for distribution

�Introduction: Moving Forward with Style

9

with the ability to achieve it) to argue for a symbiotic merger of style

and identity. As the authors foreground, style enables voices to speak

that have not been heard before. What is fresh, original, innovative,

and transformative finds voice through style because what needs to be

said comes to the surface and insists on being heard. They write: “Style

influences the ways people identify themselves as speakers and actors, as

readers and writers. Research on possible selves and analysis of the stylized identities in popular portrayals of writers . . . help us focus on how

the writerly self is made available and performed.” On a practical level,

Alexis and Leake see an important connection between possible selves

and composition researchers: “How writing is styled and how writers are

stylized on screen provides an entry point for writing studies scholars to

understand the circulation of stereotypes around writing and the cultural availability of possible writer identities.”

Laura Aull and Zak Lancaster (chapter 6) also make a strong argument for the importance of voice and identity in an emerging discursive

style. They state: “Writers’ stylistic choices . . . are driven largely by interpersonal considerations. These include the ‘voice’ or authorial persona

the writer wishes to project; the relationship with the reader the writer

seeks to create; and the writer’s engagement and negotiation with others’ views and voices in the discourse.” The authors see these stylistic

features as “resources for asking new questions about writing” and as

a way in which style brings about change by “meeting the demands of

other academic, disciplinary, and generic writing situations.” Overall,

the authors project a case for a dynamic style, mediated by voice and

identity and constantly interacting with the rhetorical situation to produce discursive change.

Digital rhetoric and the digital humanities have given us the ability

to produce new forms of meaning, with many different combinations

of verbal, nonverbal, symbolic, and multimodal tools. We argue that

style’s future in composition studies contemplates its role as the arbiter

of online expression, serving to coordinate, rearrange, and mediate

among various modes of expression. Multimodal and visual elements

produce new styles, while style offers options of ways in which these

elements can be combined. Jimmy Butts (chapter 7) sees new forms of

digital and multimodal expression as leading to what he says some may

call a “stupid style.” Claiming that “stupidity has its own power,” Butts

sees imperfection as part of stylistic innovation, urging everyone to

embrace what might seem like error. He writes: “Language will always be

deployed imperfectly, stupidly. One day, when we finally accept this, we

can be kinder to each other as more hospitable audiences of language.

Copyrighted material

Not for distribution

�10

PA U L B U T L E R , B R I A N R AY, A N D S TA R M E D Z E R I A N VA N G U R I

As such, a stupid style offers efficiencies, resistances, and sites of invention or of ‘thinking otherwise.’” Butts thus sees advantages in multimodal and digital elements of style as opening up the effects of language

and recognizing the stylistic importance in what might formerly have

been considered “error” or, to use his word, stupidity, in writing.

Congruent with this new view, compositionists have started attending

to the ways in which writers as well as speakers use language strategically

in order to convey stances, construct identities, engage in social interactions, and craft personas for a range of situations. Just as people style

their hair and clothes, they style their discourse to convey their attitudes

toward the world while expressing or performing different elements

of their identity. As Nikolas Coupland observes, style refers to “a way

of doing something” (Coupland 2009, 1). It “marks out or indexes a

social difference . . . a degree of crafting,” and production of meaning.

Someone may intentionally use an expression or part of speech to indicate their membership in a social group or to mark a level of status and

authority. Or they might stylize their discourse to perform a persona.

This view toward style recognizes it as the “fleeting interactional

moves through which speakers take stances, create alignments, and

construct personas” (Bucholtz 2009, 147). When someone decides to

incorporate a different dialect, vernacular, or slang into their writing,

they’re styling their discourse in order to construct a persona that

achieves a specific effect on readers—one that the reader may engage

with or reject. Even pronoun choice in a scholarly article qualifies as a

stylistic decision, one in which the writer is actively trying to establish a

relationship with readers and, as Olinger observes, “may index a particular class, ethnicity, gender, and/or locale” (2016, 125). Therefore,

it is not for writing teachers to accept or reject the use of a particular

nonstandard form but rather to understand why a student has chosen

one form over the other and what meanings they intend to convey to

us and other audiences. Once teachers understand and appreciate the

indexical implications behind acts of language difference, they are in a

better position to help students hone their writing across these different

codes and modes—without imposing their own agendas.

The question of language change has been at the forefront of the

field recently through the introduction of translingualism and code

meshing as the blending, merging, and meshing of accents, dialects,

and varieties of English (Young, Martinez, and Naviaux 2011). Bruce

Horner and others have said a translingual approach sees difference

in language as a resource for producing meaning in writing, speaking,

reading, and listening. Suresh Canagarajah (2013) goes on to say that

Copyrighted material

Not for distribution

�Introduction: Moving Forward with Style

11

“speaking and writing are not acts of transferring ideas or information

mechanically, but of achieving communicative objectives with art, affect,

voice, and style.”

We argue that all of these communicative objectives (art, affect, voice,

and style) are style—whether different aspects of style or different ways

we express or explain things stylistically. We recognize translingualism

and code meshing as indispensable approaches to embracing language

difference, and we also contend that the blending, merging, and effects

produced by these resources are often achieved through stylistic choice.

In the future, then, it is incumbent upon us to explore how style works in

conjunction with a translingual approach to writing in order to express

language difference in composition studies. As Bruce Horner and his

coauthors argue in their opinion essay “Language Difference in Writing:

Toward a Translingual Approach” (2011), “This [translingual] approach

thus calls for more, not less, conscious and critical attention to how writers deploy diction, syntax, and style, as well as form, register, and media.

It acknowledges that deviations from dominant expectations need not

be errors; that conformity need not be automatically advisable; and that

writers’ purposes and readers’ conventional expectations are neither

fixed nor unified” (304). In this volume, Eric House experiments with his

own translanguaging, code meshing, and the use of a “translingual style.”

House’s chapter uses hip-hop, which he calls “a valuable and generative space where discourses and language practices are continually

negotiated (Petchauer 2012),” to argue for a “translingual style” that

relies on “discourses of translingualism [to] describe difference as the

norm in language practice (Horner and Lu 2013).” House uses his

conception of a translingual style to make a generative argument for

“inscrutability,” a theoretical concept that, he argues, “invites critique

and openness” by defying normative discourses. Ultimately, House sees

the significance of inscrutability, viewed through the metaphor of the

hip-hop cipher, as promoting difference in writing studies. He states,

“An emphasis on an inscrutable style in rhetoric and composition might

then teach us the nuances of difference and its impacts on the flows and

movements in theories and pedagogies of writing.” Indeed, the idea of

an inscrutable style challenges us to re-see language as always emerging,

continually innovating.

S T Y L E F O R M S S T R AT E G Y

For Jarron Slater (chapter 9), language change comes in a different

form. He sees the classical notion of the sublime as enabling stylistic

Copyrighted material

Not for distribution

�12

PA U L B U T L E R , B R I A N R AY, A N D S TA R M E D Z E R I A N VA N G U R I

change through a transdisciplinary approach to language and discourse,

one that brings audiences and speakers or writers together through

a cooperation with each other he describes as “empowered” and

“exalted.” In the chapter, “Expectations of Exaltation,” he proposes the

notion of sublimity as originally introduced by Longinus and developed

by Kenneth Burke. For Slater, sublimity “creates expectations of exaltation and then invites the audience to fulfill those expectations through

their participatory and emancipated cooperation.” His argument builds

on Burke’s definition of the sublime as “elation wherein the audience

feels as though it were not merely receiving, but were itself creatively

participating in the poet’s or speaker’s assertion” (Burke 1969, 57–58).

According to Slater, “formal sublimity unbinds style because it shows

how style, rhetoric, and poetics are not separate ‘things’ but are forever

intertwined. Formal sublimity does not limit ‘style’ to a narrow ‘canon’

of rhetoric. Its very principle argues for a priori transdisciplinarity, one

that has style having something to say on everything from the smallest

syllable to the grandest reaches of the universe, and beyond.” For Slater,

the impact of style, and its effect on transdisciplinary change, is limitless. The use of figures, tropes, and schemes might aim not simply to

embellish or amplify discourse in a conventional sense, but to draw in

audiences as co-constructors of meaning.

Innovating style and composition studies has called on us as researchers to broaden our disciplinary identities, seeking to understand who

else studies style and what methods and terms they use. Scholarship in

sociolinguistics and discourse studies has expanded the horizons of stylistic study. As such, we have solicited work from scholars who cross disciplinary boundaries, drawing on corpus and discourse studies. Corpus

studies by Zak Lancaster have already helped us investigate the accuracy

of language patterns in textbooks such as They Say/I Say, specifically the

extent to which they truly represent discourse conventions in academic

writing. Laura Aull’s (2015) work on first-year writing has also generated reliable, data-driven insights into students’ acquisition of subjective pronouns, in order to counter myths about use of the first-person

in academic writing. Further corpus investigations of style will help us

learn more about the ways in which people use language interactively

and indexically.

Contributions by Laura Aull and Zak Lancaster show the power of

linguistic analysis to inform students’ acquisition and navigation of academic discourse. In their co-authored chapter, “Stance as Style” (chapter 6), Aull and Lancaster demystify aspects of academic conventions by

identifying “highly patterned stylistic features” and illustrating how “the

Copyrighted material

Not for distribution

�Introduction: Moving Forward with Style

13

unique stylistic qualities of academic prose become especially visible

when seen through the lens of stance,” which the authors define as “the

writers’ many ‘micro’ expressions of attitudes, evaluations, epistemic

commitment, and interaction with the reader.” Their chapter outlines

three major stances that occur in academic prose along with corresponding features such as attitude markers, self-mentions, concessions,

adversative connectors, hedges, and boosters. They show how instructors can introduce these terms to students, grounding their discussion

in helpful examples of student writing and classroom activities.

Laura Aull’s single-authored chapter, “A Civil Style” (chapter 10),

also employs functional linguistics and discourse analysis in order to

introduce a new term, “diplomatic evidentiality” (a civil style that, in

Aull’s words, features “both ‘rhetorical listening’—a stance of openness

in relation to other texts and views [Ratliffe 2005]—and a writer’s own

convictions, in that order”), into current approaches to civil discourse in

college writing instruction. As Aull notes, research on civil discourse has

curiously overlooked the role of actual language strategies and markers.

Attending more closely to stance markers and evidentials, Aull claims,

gives writers ways of “projecting honesty, modesty, and proper caution in

self-reports, and for diplomatically creating research space in areas heavily populated by other researchers” (Swales, quoted in Aull 1990, 175).

Here, teachers can see how style contributes to much more than adherence to rules or conventions. In fact, the choices they make in diction

and sentence construction contribute to the overall stance and attitude

that readers will perceive, which in turn affects their reception. Such

work confirms and reminds us about the importance of language, tone,

and voice and their role in mitigating or exacerbating conflicts—as

when politicians and celebrities alike seem to enjoy exchanging barbs

over social media, only elevating the toxicity of public discourse. By

pointing to the importance of ethics and civility in the discursive realm,

Aull helps the field reimagine a discourse, based on diplomatic evidentiality, that reinvents the very nature of argument, effectively rebalancing

logos, pathos, and ethos within the rhetorical situation.

We have also worked to expand our understanding of writing and

where it happens. Writing doesn’t just occur in the academy, and stylistic

innovations appear on the web every day through new words, new turns

of phrase, and new grammatical constructions. To fully understand style,

we need to study it in personal journals, newspapers, blogs, and social

media. A turn toward quantitative, empirical data also characterizes the

new direction in the study of style. Until recently, studies of style have

been limited by a tendency to form a general impression of a writer’s

Copyrighted material

Not for distribution

�14

PA U L B U T L E R , B R I A N R AY, A N D S TA R M E D Z E R I A N VA N G U R I

style, or to speculate about the effects of stylistic decisions on readers.

Work on corpus linguistics offers new and better tools for studying

meaningful patterns across large bodies of texts. Doing so allows us

to make stronger, more reliable claims about the stylistic conventions

within a certain discipline or genre. It also enables us to see with greater

precision how writers negotiate, deviate, and innovate with regard to

these expectations.

While discourse-based studies have always attended to the study of

language in action, stylistic analysis adds a new dimension by showing

how style, or stylization, is used to bring about a reversal in the very

nature of discourse. What is notable here is that discourse, almost always

closely connected to different genres, has been used to achieve specific

effects. But style disrupts conventional genres, turning discourse on its

head to expose inherent biases in language, gender, social interactions,

and culture. It calls discourse into question and, in the process, engenders a new form of discourse inherently connected to, but changed

from, its original forms. For Almas Kahn (chapter 11), legal discourse

takes on new forms through the work of Applied Legal Storytelling

(ALS), in which authors often begin with personal stories or vignettes

for the purpose of “humanizing real-life actors in the legal system”

through style, using tone, imagery, allusions, diction, and other features.

ALS discourse gives new life to legal reasoning through its stylistic possibilities. In the case of a transgender bathroom rights case, Kahn argues,

the judge cites a teen’s “compelling statement” to a school board in the

teen’s YouTube video, bringing in visual and digital rhetoric, and forging a new, emergent form of legal discourse.

In “What Style Can Add to Genre” (chapter 12), Anthony Box suggests that strengthening connections between disciplinary writing and

style can increase genre awareness. When writers are aware of the stylistic options available to them and can consciously choose them, they

are better equipped to “question, interact with, and redefine the genres

they participate in.” However, style is often incorporated superficially in

academic writing, out of habit rather than choice. As an example, Box

analyzes the “faked coherence” present in metalanguage within samples

of published prose. Instead, he argues, an internalized stylistic awareness can lead to variety, originality, and memorability.

S T Y L E C R E AT E S A N D T R A N S C E N D S B O U N DA R I E S

As style relates to both convention and deviation, it serves participatory, community-establishing functions, while also acting as gatekeeper.

Copyrighted material

Not for distribution

�Introduction: Moving Forward with Style

15

Recent scholarship demonstrates how style reinforces and disrupts

genre boundaries, disciplinary boundaries, and divisions between public

and private. In an important article that drew a well-known response

from Charles Bazerman, Anthony Fleury proposes that skills in public

speaking are emblematic of styles of communication. He writes:

Liberal education can be advanced through strategic use of core

styles throughout the curriculum. Core styles of expression, exposition, and persuasion—which are foundational to but transcend disciplinary styles—provide tools for understanding, performing, critiquing, and resisting knowledge and identity production. A dialectic of

Communication Against the Disciplines and CID [Communication in the

Disciplines] would encourage in students multiple and diverse ways of

thinking and doing. Approached this way, CXC [Communication Across

the Curriculum] can help the student become a model citizen, able to not

only argue well for a position but embody a democratic mix of multiple

voices, to articulate the world from many positions. (2005, 72)

Even though Fleury was primarily addressing readers in communications

studies, his remarks have been widely taken up in the field of rhetoric

and composition. Bazerman, for instance, suggests that “advocates of the

centrality of style, such as Fleury, may find ways of talking about how the

styles that disciplines use to express their intellectual work are closely tied

to the life, meaning, and accomplishment of these knowledge-creating

communities” (2005, 89). Bazerman continues in a statement relevant to

the current volume, stating, “This close connection between the styles of

communication and the most fundamental projects, meanings, and vitality of the disciplines has made the study of disciplinary writing and the

practice of writing across the curriculum deeply rewarding and engaging

endeavors” (89). What is striking is the relevance of Fleury’s remarks, not

to mention Bazerman’s, to what authors in this volume have contributed

in this area, especially the emphasis on multiple voices coming from interdisciplinary stylistic approaches.

In “Points of Departure” (chapter 13), Jon Udelson addresses the

recriminations some face in “trespassing” a disciplinary Maginot Line

between creative writing and composition studies. In his chapter,

subtitled “Composition and Creative Writing Studies’ Shared Stylistic

Values,” he writes: “The ability to style one’s writing by the common conventions of a particular discipline . . . aids in marking a writer as part of

the discipline and the believed epistemological terrain it governs. From

a disciplinary perspective, treading that terrain otherwise constitutes

an act of trespassing.” In a sign of the change signaled by the authors

in this collection, Udelson aims to trespass, to usher in a new level of

communication, erasing the truism that “[c]omposition cannot speak of

Copyrighted material

Not for distribution

�16

PA U L B U T L E R , B R I A N R AY, A N D S TA R M E D Z E R I A N VA N G U R I

creative writing because composition is still all too often thought of as

the domain of ‘general writing skills instruction’ (Petraglia 1995), while

creative writing exists in a domain beyond mere ‘skill.’” Udelson invites

trespass as a new way to erase the divide between the two fields and allow

new possibilities to emerge across disciplines.

Mike Duncan (chapter 14) uses his skillful analysis to take up different disciplinary approaches and discover the truth about stylistic forgery

in the New Testament. He writes: “Similar style could easily mean the

opposite—a ‘school’ of forgers writing in that style, borrowing the ethos

of the original. Accordingly, I argue that a stylistic imitator . . . wrote

Acts—and that all the evidence arrayed in support of common authorship can be reversed to support two different authors.” In suggesting

that scholars look seriously at “critical factual inconsistencies,” he argues

that “ultimately, the initial sensing of ‘something’s off’ may happen at

the style level, but defensible proof of ‘something’s off’ requires close

reading of content and context.”

William FitzGerald (chapter 15) offers the metaphor of the writing

classroom as makerspace and style as craft to argue for renewed attention

to the word in composition. Like all makers, writers must have comfort

and fluency with the tools they use to create. Yet students often “arrive

at college poorly resourced in terms of lexis.” By increasing our attention to the word in composition pedagogy, we can “help students better

access and leverage their stock of verbal resources.” To make a case for

a lexical pedagogy that interweaves style and invention, FitzGerald looks

to the past, to the dominant narratives in our discipline that have either

outright rejected style or emphasized sentences over words. The essay

leaves us to imagine a pedagogical approach that treats style as “tinkering” and empowers students to explore, play with, and master the “material dimensions of words and the labor that adds to their value.” Indeed,

FitzGerald argues that we make space for style and style makes space for

emergent and inventive meanings.

CONCLUSION

We argue that style stands at the future of composition studies. We see

it as an open frontier that invites crossing divides, providing access,

and celebrating difference. The contributions to this collection recognize style as inventive and innovative and prompt us to consider a

number of ways to harness these attributes. They urge us to see style

as a tool for engaging audiences through dynamic co-construction of

meaning, recalibrating binaries, renegotiating identities, and traversing

Copyrighted material

Not for distribution

�Introduction: Moving Forward with Style

17

disciplinary spaces. We hope readers will come away from our collection

with an understanding of how to use style for opening up new emergent

approaches to writing, reading, thinking, and cross-disciplinary collaboration. We see style as contributing to the growth of the discipline, now

and in the future. As editors, we focused our efforts on guiding individual contributors and on shaping the volume to help ensure its parts

speak dialogically, collaboratively, collectively, and divergently and move

across, between, among, and around questions, ideas, and meanings.

The general public may still define style by way of conventional manuals

like Strunk and White’s influential but outdated Elements of Style. Even

here, public intellectuals such as Steven Pinker (2015) have challenged

conventional ways of thinking about style, moving discourse away from

platitudes about correctness and convention and toward more nuanced

approaches that embrace the inevitable mutability of language. While

linguistic purists might bemoan the appearance of new words and

phrases in the wake of momentous events and sociopolitical upheaval,

contemporary stylisticians welcome them and see them as central catalysts for effective communication. As realities change, so must the styles

we use to convey our perceptions of them. Nevertheless, the future work

of rhetoricians will always involve efforts to counter the myth that style

only involves following rigid rules about grammar and usage.

We see stylistically engaging writing in a broad range of genres and

disciplines. Not only that, but style often plays a key role in the evolution

of these written forms. Writers refashion these forms themselves, finding

new ways to make meaning through manipulation of the existing stylistic conventions and constraints. In every case their stylings of discourse

facilitate their intentions and reinvent the forms of writing they use. As

much as any other canon or approach to rhetoric, style fosters agency

and ingenuity in language. One shared goal among all teachers and

researchers in our discipline lies in the value we see and promote in

such autonomy and adaptability.

Every single chapter in this collection conveys one inflection of our

central message about the inventive, generative potential of style. It may

involve innovations on the sentence level or regarding word choice.

More broadly, attunement to style offers new approaches to a variety of

aspects within the discipline, from writing across the curriculum to the

role of civil discourse in first-year composition. Just as changing knowledge in the discipline has influenced the way stylisticians think about

language, we hope that new knowledge in style will give teachers and

researchers concepts, frameworks, and strategies for attending to the

stylistic dimensions of our shared endeavors, now and into the future.

Copyrighted material

Not for distribution

�18

PA U L B U T L E R , B R I A N R AY, A N D S TA R M E D Z E R I A N VA N G U R I

REFERENCES

Aull, Laura. 2015. First-Year University Writing: A Corpus-Based Study with Implications for Pedagogy. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bazerman, Charles. 2005. “A Response to Anthony Fleury’s ‘Liberal Education and Communication against the Disciplines’: A View from the World of Writing.” Communication

Education 54 (1): 86–91.

Bergeron, Kat. 2006. “SLABBED! and Other Katrinaed Words; Katrina Patina.” Sun Herald

(Biloxi, MS), May 21, 2006. Sunherald.com.

Bucholtz, Mary. 2009. “From Stance to Style: Gender, Interaction, and Indexicality in Mexican Immigrant Youth Slang.” In Stance: Sociolinguistic Perspectives, edited by Alexandra

Jaffe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Butler, Paul. 2008. Out of Style. Reanimating Stylistic Study in Composition and Rhetoric. Logan:

Utah State University Press.

Canagarajah, Athelstan Suresh. 2013. Translingual Practice: Global Englishes and Cosmopolitan

Relations. London: Routledge.

Carillo, Ellen. 2010. “(Re)Figuring Composition through Stylistic Study.” Rhetoric Review

29 (4): 379–394.

Carillo, Ellen. 2014. Securing a Place for Reading in Composition: The Importance of Teaching for

Transfer. Logan: Utah State University Press.

Coates, Ta-Nehisi. 2015. Between the World and Me. New York: Random House.

Connors, Robert J. 2000. “The Erasure of the Sentence.” College Composition and Communication 52: 96–128.

Coupland, Nikolas. 2009. Style: Language Variation and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Duncan, Mike, and Star Medzerian Vanguri. 2013. The Centrality of Style. Fort Collins: The

WAC Clearinghouse.

Fleury, Anthony. 2005. “Liberal Education and Communication against the Disciplines.”

Communication Education 54 (1): 72–79.

Foucault, Michel. 1994. The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. New York:

Vintage Books.

Halliday, M.A.K., and Christian Matthiessen. 2014. Halliday’s Introduction to Functional

Grammar. New York: Routledge.

Holcomb, Chris, and M. Jimmie Killingsworth. 2010. Performing Prose: The Study and Practice

of Style in Composition. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Horner, Bruce, and Min-Zhan Lu. 2013. “Translingual Literacy, Language Difference, and

Matters of Agency.” College English 75 (1): 586–611.

Horner, Bruce, Min-Zhan Lu, Jacqueline Jones Royster, and John Trimbur. 2011. “Opinion: Language Difference in Writing: Toward a Translingual Approach.” College English

73 (3): 303–321.

Lancaster, Zak. 2016. “Do Academics Really Write This Way? A Corpus Investigation of

Moves and Templates.” In “They Say / I Say.” College Composition and Communication 67

(3): 437–464.

Lanham, Richard. 2007. The Economics of Attention: Style and Substance in the Age of Information. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

MacDonald, Susan Peck. 2007. “The Erasure of Language.” College Composition and Communication 58 (4): 585.

Ochs, E. 1992. “Indexing Gender.” In Rethinking Context: Language as an Interactive Phenomenon, edited by D. Alessandro and C. Goodwin, 335–358. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Olinger, Andrea R. 2016. “A Sociocultural Approach to Style.” Rhetoric Review 35 (2):

121–134.

Copyrighted material

Not for distribution

�Introduction: Moving Forward with Style

19

Pace, Tom. 2009. In Refiguring Prose Style: Possibilities for Writing Pedagogy, edited by T. R.

Johnson and Tom Pace.

Pinker, Steven. 2015. The Sense of Style: The Thinking Person’s Guide to Writing in the 21st Century. New York: Penguin Books.

Ratcliffe, Krista. 2005. Rhetorical Listening: Identification, Gender, Whiteness. Carbondale:

Southern Illinois University Press.

Ray, Brian. 2014. Style: An Introduction to History, Theory, Research, and Pedagogy. Fort Collins,

CO: The WAC Clearinghouse.

Vance, John. 2014. “Pedagogy: Reconsiderations and Reorientations.” PhD diss., University of Louisville, Louisville, KY.

Young, Vershawn Ashanti. 2004. “Your Average Nigga.” College Composition and Communication 55 (4): 693–715.

Young, Vershawn Ashanti, and Aja Martinez, with Julie Anne Naviaux. 2011. “Introduction: Code-Meshing as World English.” Code-Meshing as World English: Pedagogy, Policy,

Performance. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Zirin, Dave. 2007. “And Still They Rise: Confronting Katrina.” Rising Tide Blog. The Rising

Tide Conference 2. August 29, 2007.

Copyrighted material

Not for distribution

�

LL Aull

LL Aull