Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser.

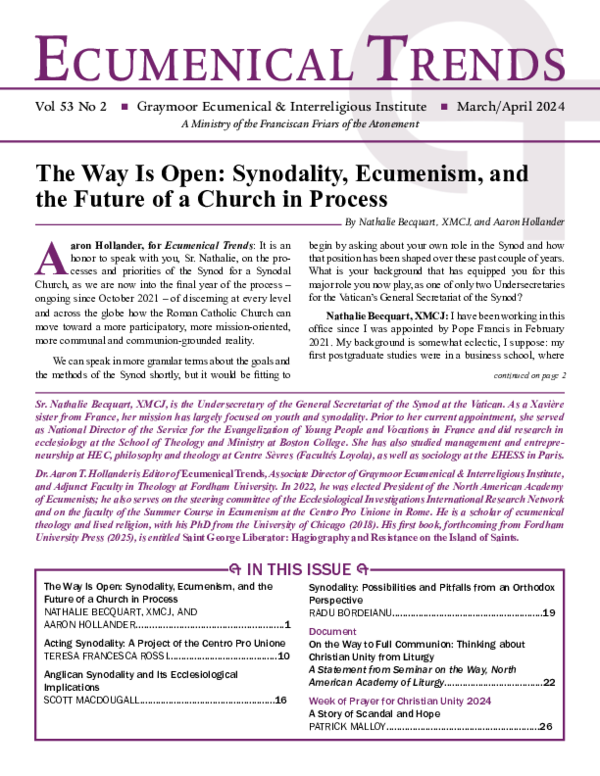

“Synodality: Possibilities and Pitfalls from an Orthodox Perspective”

“Synodality: Possibilities and Pitfalls from an Orthodox Perspective”

2024, Ecumenical Trends

“Synodality: Possibilities and Pitfalls from an Orthodox Perspective,” in Ecumenical Trends 53, no. 2 (March/April 2024): 19-21.

Related Papers

Faculty of Theology of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki

THE SYNODICAL PRINCIPLE AS THE KEY TO CHURCH UNITYAGAINST THE BACKGROUND OF THE HOLY AND GREAT COUNCIL2020 •

This paper was presented at the 8th International Conference of Orthodox Theology. Under the Auspices of the Ecumenical Patriarchate. The Conference was hosted by A.U.Th., and took place in Thessaloniki, Greece, from May 21-25, 2018, with the title “The holy and Great Council of the Orthodox Church: Orthodox Theology in the 21st Century”.

A thorough examination of the various ecclesiological problems arising from misapprehensions of conciliarity in history and theory. The list of misapprehensions of synodality is very long. The author discusses some of the most fundamental questions that have been heard in the recent comments about the Holy and Great Council in Crete and false information regarding some important aspects of the Great Council, such as the composition of the council, the number of its participants, the way of signing, the significance of episcopal signatures, the issue of voting, and more. From the book: Synodality - A Forgotten and Misapprehended Vision: Reflections on the Holy and Great Council of 2016.

Louvain Studies

Expressions of the Church's Synodality in the Life and Mission of the Romanian Orthodox2020 •

This paper outlines the way in which synodality is currently organized and lived within the Romanian Orthodox Church. To this end, the theological and spiritual foundations of the principle of synodality are highlighted first, as well as the embodiment of this principle, as an ecclesial reality at once permanent and dynamic, in different synodal structures of the Orthodox Church. The Romanian expressions of the synodality of the Orthodox Church are then presented with a view on the Statutes for the Organization and Functioning of the Romanian Orthodox Church, republished in 2020. https://poj.peeters-leuven.be/secure/POJ/downloadpdf.php?ticket_id=608c694cc6b27

2013 •

The issue of the Orthodox participation in the Ecumenical Movement in general, and in the WCC in particular, remains always a timely and challenging topic for discussions and deliberations, not only among the Orthodox specialists, clergy and professors, who are directly involved in that matter, but also among the Orthodox faithful. The variety of divergent opinions1 extends from a wholehearted support of a complete and active Orthodox participation in the process of searching for Christian unity to a more cautious and critical stance on it. Some conservative Orthodox circles have expressed even an absolute and fundamentalist opposition to any kind of rapprochement among the Christian Churches. These alignments constitute the scope of the Orthodox understanding and interpretation of Ecumenism, not only during the previous decades, but also nowadays. It is generally acknowledged that the last decade of the 20th century was the most problematic and painful period concerning the Orthodox participation in the WCC. The Orthodox Church, which, under the relevant initiatives of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, had a pioneering role in the formation of the Ecumenical Movement from the very beginning of the 20th century, found herself in difficulties relating to her position in the WCC. Indeed, the Churches of Georgia and Bulgaria withdrew their membership from the WCC and the Conference of European Churches (CEC); Georgia in 1997, followed by Bulgaria in 1998. 1. Archbishop Iakovos of America, “The Orthodox Churches vis-à-vis the Ecumenical Movement”, in The Catholic World, vol. 201, no. 1, April 1965, 237- 239. Moreover, a significant and perilous rekindling of anti-ecumenical Orthodox circles was manifested during the 1990’s, especially in the former Soviet countries after the fall of communism. That crisis in the relations of the Orthodox Church with the Ecumenical Movement led the 8th General Assembly of the WCC in Harare (1998) to appoint a Special Commission on Orthodox participation in the WCC. Motivated by that reality, due to the fact that I was studying between 2004 and 2005 in the official Institute of the WCC, at Bossey, and the Autonomous Faculty of Protestant Theology of the University of Geneva, I considered it important to study further the issue and deepen my understanding of the Orthodox involvement in the Ecumenical Movement. More specifically, in this dissertation I try to explore the official Orthodox position vis-à-vis the Ecumenical Movement as it had been formulated by the official synodical bodies of the Orthodox Church in her process of convoking the Holy and Great Council. The convocation of the Holy and Great Council was envisioned as an attempt of the Orthodox Churches to come closer and deal on a Pan- Orthodox level with the main issues that confronted them in the 20th century. After many centuries of mutual isolation and alienation, the process of meeting of the Orthodox Churches was only put into practice during the 1960’s, even though this issue occupied the thought of the Orthodox leaders from the very beginning of the 20th century. Among the themes of the agenda of the Holy and Great Council, the issue of Ecumenism and inter-Christian relations had a primary place. While dealing with the issue of the Orthodox participation in the Ecumenical Movement, I will try to answer the following questions: Is the participation of the Orthodoxy in the Ecumenical Movement and in its institutional forms, such as the WCC, based on firm principles logically applied? Are there any divergences or shifts in the attempt of the Orthodox Church to articulate her official position concerning her presence in the Ecumenical Movement? If so, how can they be explained? How can one analyze the changing attitudes of Orthodoxy vis-à-vis the orientation of the Ecumenical Movement and of the WCC after a common decision (1986) has been reached on a Pan-Orthodox level? Has that common decision a binding character for the autocephalous Orthodox Churches? In my attempt to answer to those questions, I focused my research on studying the formal decisions taken by the Orthodox Churches on a Pan-Orthodox level. My study was based on the Encyclicals, official Church documents and minutes of Pan-Orthodox Conferences and Ecumenical Assemblies and Consultations, as well as on related articles and essays. In addition, influential personalities involved in the WCC activities and in the Pan-Orthodox Preconciliar process have been interviewed. Despite the fact that this topic also touches ecclesiological aspects, my purpose was to deal with all these sources by limiting myself to a historic point of view until the work performed by the well known Special Commission on Orthodox participation in the WCC (1998-2002) was completed. The chronic limit (2002) is exclusively related to the time when this Master’s thesis was written (2004-2005), namely before the convocation of the Porto Alegre 9th General Assembly of the WCC, where the proposals of the Special Commission on Orthodox participation in the WCC were adopted and put into practice.

Full text: https://ojs.tnkul.pl/index.php/rt/article/view/16777 --- This article contributes to the growing body of literature on synodality with a comprehensive introduction. Firstly, the author observes the link between the synodal approach promoted by Pope Francis and the Second Vatican Council. With the help of Myriam Wijlens' term 'reconfiguration,' he then discusses the theological foundations of a synodal understanding of the Church. Synodality recontextualizes the bishop's responsibility by situating it within the community of the faithful. In addition, as the Holy Spirit is the main actor in the synodal process, all the faithful, including bishops, have to listen to what He is saying, a task that requires discerning the spirits. In the third place, the author focuses on the reconfiguration of ecclesial practice. In a synodal way of proceeding, the traditional virtue of obedience is complemented by various other virtues, such as speaking out, listening with interest, and a deep openness to the Spirit's newness. Finally, the author identifies practical issues that need attention.

Semi-Annual Bulletin Centro Pro Unione

Le développement actuel de la synodalité au sein de l’Église catholique : promesses, difficultés, attentes. Un point de vue orthodoxe2021 •

Ecumeny and Law

The Regime of the Synodality in the Eastern Church of the First Millennium and Its Canonical Basis2019 •

The synodal form of organisation — sought and established for His Church by Her Founder, that is, by Our Lord Jesus Christ, and affirmed by His Apostles — was also expressly reaffirmed by the canonical legislation of the Eastern Church of the first millennium. By adapting the form of administrative-territorial organisation of the Church to that of the Roman State — sanctioned by the canons of the Ecumenical Synods (cf. can. 4, 6 Sin. I Ec.; 2, 6 Sin. II Ec.; 9, 17, 28 Sin. IV Ec.; 36 Sin. VI Ec.) — in the life of the Eastern Church several types of synods appeared, starting with the eparchial (metropolitan) synod of a local Church and ending with the patriarchal synod, both still present in the autocephalous Churches of Eastern Orthodoxy.

RELATED PAPERS

DAMPAK EKONOMI DARI COVID-19 (VIRUS CORONA) TERHADAP SEKTOR PENERBANGAN DI INDONESIA SERTA UPAYA PEMERINTAH DALAM MENGATASINYA

DAMPAK EKONOMI DARI COVID-19 (VIRUS CORONA) TERHADAP SEKTOR PENERBANGAN DI INDONESIA SERTA UPAYA PEMERINTAH DALAM MENGATASINYA2020 •

Latin American and Latinx Visual Culture

Diego Rivera: Mujeres en el mural Viernes de Dolores en el canal de Santa Anita2023 •

Acta Scientiarum. Biological Sciences

Antibacterial activity and chemical composition of essential oil of Lippia microphylla Cham2011 •

Miscelánea Comillas. Revista de Ciencias Humanas y Sociales

Democratización del acceso a la educación superiorTransplantation

Cyclosporin a Suppresses Α-Galactosylceramide (Galc) – Induced Activation and Apoptosis of Mouse NKT Cells2004 •

Choice Reviews Online

The birth of capitalism: a twenty-first-century perspective2012 •

SER Social TRABALHO, LUTAS SOCIAIS E SERVIÇO SOCIAL

Subjectivity and hypervulnerability in consumption by elderly2024 •

Radu Bordeianu

Radu Bordeianu