24

DASHARATHA’S OIL VAT IN THE

MEWAR RAMAYANA

Subhashini Kaligotla

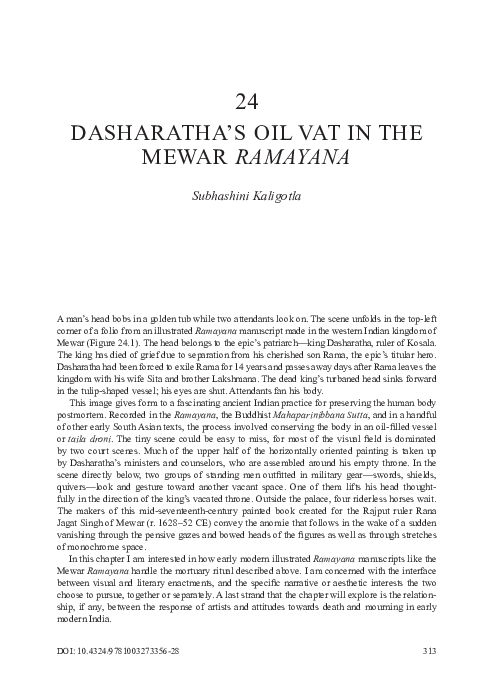

A man’s head bobs in a golden tub while two attendants look on. The scene unfolds in the top-left

corner of a folio from an illustrated Ramayana manuscript made in the western Indian kingdom of

Mewar (Figure 24.1). The head belongs to the epic’s patriarch—king Dasharatha, ruler of Kosala.

The king has died of grief due to separation from his cherished son Rama, the epic’s titular hero.

Dasharatha had been forced to exile Rama for 14 years and passes away days after Rama leaves the

kingdom with his wife Sita and brother Lakshmana. The dead king’s turbaned head sinks forward

in the tulip-shaped vessel; his eyes are shut. Attendants fan his body.

This image gives form to a fascinating ancient Indian practice for preserving the human body

postmortem. Recorded in the Ramayana, the Buddhist Mahaparinibbana Sutta, and in a handful

of other early South Asian texts, the process involved conserving the body in an oil-filled vessel

or taila droni. The tiny scene could be easy to miss, for most of the visual field is dominated

by two court scenes. Much of the upper half of the horizontally oriented painting is taken up

by Dasharatha’s ministers and counselors, who are assembled around his empty throne. In the

scene directly below, two groups of standing men outfitted in military gear—swords, shields,

quivers—look and gesture toward another vacant space. One of them lifts his head thought-

fully in the direction of the king’s vacated throne. Outside the palace, four riderless horses wait.

The makers of this mid-seventeenth-century painted book created for the Rajput ruler Rana

Jagat Singh of Mewar (r. 1628–52 CE) convey the anomie that follows in the wake of a sudden

vanishing through the pensive gazes and bowed heads of the figures as well as through stretches

of monochrome space.

In this chapter I am interested in how early modern illustrated Ramayana manuscripts like the

Mewar Ramayana handle the mortuary ritual described above. I am concerned with the interface

between visual and literary enactments, and the specific narrative or aesthetic interests the two

choose to pursue, together or separately. A last strand that the chapter will explore is the relation-

ship, if any, between the response of artists and attitudes towards death and mourning in early

modern India.

DOI: 10.4324/9781003273356-28 313

� Subhashini Kaligotla

Figure 24.1 �

Dasharatha’s Droni, Folio from Jagat Singh’s Ramayana (f.82R), Mewar, ca. 1650–1652,

watercolor on paper. Courtesy of The British Library Add. MS 15296(1).

The Ramayana is at once an epic poem (kavya) that circulated in ancient India and the distinctive

cultural product of an interpretive community like seventeenth-century Mewar. It began its tenure

as an oral composition recited by bards before being written down around 750–500 BCE in the

Sanskrit language. The earliest Sanskrit composition is attributed to Valmiki and celebrated as the

first poem (adi kavya), running to a whopping 24,000 verses divided across seven books (kandas).

The text itself is self-conscious about its authorship, citing Valmiki both as creator and character

in the story’s drama, although his historicity is uncertain.1 Since Valmiki, the tale has been told and

re-told in every conceivable South and Southeast Asian language, including numerous Sanskrit

tellings, and in a staggering range of media. Visual enactments include medieval temple sculpture,

large format painted textiles, and deluxe manuscripts like the Mewar Ramayana that include both

pictures and words. Alongside these are responses in dance, drama, puppet theater, film, novels,

lyric poetry, comic books, and an array of premodern and modern media.

The Mewar Ramayana narrates the entirety of the epic tale, and maintains strong affinities

with the Valmiki text, including the original’s seven-book organization scheme. In its extant form

the book (rather, set of books) contains 414 paintings out of an original 450.2 What is certain is

that a single individual—a Jain scribe named Mahatma Hirananda—wrote the Sanskrit text, in

Devanagari script. The text was written in black ink and interleaved with the paintings, with the

two generally keeping pace with one another except in rare instances.3 By contrast, the proven-

ance of the accompanying paintings is far more complicated. Scholars trace at least three distinct

visual styles and attribute the paintings to the ateliers of two known Mewar master painters—

Sahibdin and Manohar—and an unknown painter of possible Deccan origins (Dehejia 303–304).

Today, the manuscript’s individual books are dispersed across collections in London, Mumbai,

Udaipur, and Baroda, with four books in the possession of the British Library.

Scholars have theorized the Ramayana’s plurality variously: the Ramayana has been under-

stood as a literary genre and likened to a library or a language (Pollock, “Rāmāyaṇa and Political

Imagination in India” 288). Ramayanas have been compared to translations exhibiting divergent

relationships to canonical accounts like the Sanskrit Valmiki or the Tamil Kampan (Ramanujan,

“Three Hundred Rāmāyaṇas”). In my own writing, I have argued that the Ramayana is a site of

ekphrasis, provoking creative engagements across media and in interart media (Kaligotla “Words

and Pictures”).

314

� Dasharatha’s Oil Vat in the Mewar Ramayana

With this background in mind, let’s return to the vessel in which Dasharatha’s body was tem-

porarily interred. That scene is from the epic’s second book—the Ayodhya Book, named for the

capital city from which the king ruled. The first book or Book of Youth tells of the miraculous

birth of Rama and his three brothers, their princely upbringing, and marriages. The Ayodhya Book

sees Rama’s banishment on the eve of his coronation, orchestrated by Dasharatha’s favorite wife

Kaikeyi, who covets the throne for her own son Bharata. Later books follow Rama, Sita, and

Lakshmana into exile, chronicle Sita’s abduction by demon lord Ravana, and Rama’s battle with

Ravana, signifying the cosmic struggle between good and evil. But those events need not con-

cern us. Back in Ayodhya, Dasharatha dies of sorrow in the aftermath of Rama’s departure for

the forest. Our painting takes us to the moment after his death. Ramayana receivers would have

understood the need to preserve the monarch’s body as none of his sons was in the capital to per-

form his funeral rites, as required by custom. His two oldest boys, Rama and Lakshmana, had

of course been exiled, and his two remaining offspring, Bharata and Shatrughna, were away in

their maternal grandfather’s kingdom. The king’s ministers therefore “took the lord of the world

[Dasharatha] and placed him in a vat of sesame oil” (Pollock, The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki: An Epic

of Ancient India 213/ Rām II.60.12)—the vessel in the top corner of our painting, set against an

olive-green background.

Then, messengers were sent to summon Bharata and Shatrughna. The four horses waiting out-

side the palace enclosure, directly below the vessel, are meant then for the four men standing

closest to the animals (Figure 24.1). The man at the head of the group is in dialogue with family

priest Vasishtha, who is instructing the men to hurry to Rajagrha, where the princes are staying.

Meanwhile, even before learning the news and on the very night that the messengers set out

from Ayodhya, Bharata spends a troubled night. His dreams feature his father and various ill

omens. Bharata recounts his nightmares to his concerned companions the next morning. Crucially,

sesame oil (taila) and the vat of oil (taila droni) play a prominent part in Bharata’s dream. The

corresponding text (which appears on f.83v) first describes many portents, as told by the prince: the

moon falls to the earth, the oceans dry, and the sun is swallowed up by the demon Rahu. Bharata

then sees his father dragged to the southern direction, typically associated with death and the god

of death, Yama. Next, his father reappears, this time

smeared with oil, his hair wild, falling from the peak of a mountain into a deep pond of

cow dung. Sunk in that pond, I saw how he was drinking sesame oil [taila] with his hand

from that dung-pond, while he laughed again and again […]. Having consumed the taila-

odana [literally “oil-food”] again and again, his body smeared with sesame oil, he plunged

headfirst into the mass of oil.4

For Bharata, the meaning of these sinister visions is clear: they bode ill for his father’s

wellbeing.

Sesame oil and immersing the body in oil appear to work in various ways in the Ramayana.

When we first encounter the practice, it is clearly an embalming procedure, which, according to

several texts in addition to the Ramayana, was known in ancient India.5 Early Buddhist texts,

too, show knowledge of the mortuary practice. The Pali Mahaparinibbana Sutta and its Sanskrit,

Tibetan, and Chinese counterparts contain variations on the account of the historic Buddha’s last

days, the honors paid to his body, as well as those in attendance. Critically, all affirm the use of

the oil-filled vessel.6 In fact, the parallels between the treatment of the Buddha’s body and that of

Dasharatha are striking. Like Dasharatha, the Buddha was not immediately cremated.7 Moreover,

a seven-day delay followed his decease, suggesting to some that the body of the Buddha was kept

315

� Subhashini Kaligotla

in oil to prevent it from decay until Mahakashyapa, his foremost disciple, could perform the last

rites.8 Similarly, in the Ramayana, Dasharatha’s ministers submerge the king’s body in the oil-

filled vat and keep it there until his funeral. Bharata gets back to Ayodhya only seven nights after

receiving the summons. Once he arrives, he performs the required rituals, which include cremation

and the twelfth-day shraddha ceremony. But first, the mourners must retrieve Dasharatha from the

oil vat. Bharata’s immediate impression of his father’s face is that it had a “yellowish tinge and

he seemed to be asleep” (Pollock, The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki 232/ Rām II.70, 4–5). Presumably

that lifelike effect could not have been achieved without the body’s conservation in oil.9 A second

meaning for the taila droni comes from the reactions of the court ladies to whom recourse to the

vessel signals that the king was neither ill nor slumbering but had transitioned into the afterlife.

According to the narrative, the women had spent the night in the king’s company and found him

unresponsive in the morning. His ministers’ decision to immerse the monarch in a vat of oil was

thus akin to a contemporary doctor calling time of death. It confirmed that there was no going

back. And so, the women began to wail unconsolably. A third and final meaning is suggested by

Bharata’s dream, where it is not the oil-filled vessel per se but the oil itself that portends death.

While Bharata envisions other terrifying omens, it seems to me that the text (especially that used

in the Mewar manuscript) puts particular emphasis on the oil. Dasharatha is coated in oil, ingesting

oil over and over, and is eventually entirely submerged in oil. It is only through Bharata’s dream,

then, that Ramayana receivers experience the oil immersion from Dasharatha’s somatic perspec-

tive, for the initial description of his ministers’ actions is perfunctory. The rich sensory details

and the repetition of the word taila help us see Dasharatha filling with oil and sinking further and

further into the unction, which was exactly what was happening to his physical body as Bharata

dreamt.

In sharp contrast, the painters of Mewar’s Ayodhya Book chose to enact a completely different

feature of the prince’s nightmares, involving an interaction between the king and a woman, which

feels, to my mind, less crucial to the text. In other words, other than the small segment in the

left corner of folio 82r (Figure 24.1), the king’s oil immersion receives little attention visually.

Is this because the mortuary process itself was alien to the painted Ramayana’s contemporary

seventeenth-century audience and its visual artists? Another way to put it: does the choice reflect

sensitivity to contemporary taboos or knowledge? Or perhaps the decision to exclude the scene

was motivated by technical constraints—space issues or even the difficulty of representing the

dream’s complexities in the tight pictorial frame allocated by a painting supervisor?

It is worth pointing out that Bharata’s dream follows the taila droni scene, with just a page of

text separating the two images. Notably, both paintings are divided into three visual fields with

distinct scenes confined to each field. In the latter painting, the left half of the picture plane shows

the four messengers arriving in Rajagrha to summon Bharata (Figure 24.2). The right half of the

picture is organized vertically into two registers, both depicting interior space. The top register

shows the sleeping prince’s bed chamber and attendants attempting to wake him. The third and

final scene, set in the space below the bedchamber, is meant to represent the prince’s dream.

Whereas Bharata witnesses many terrifying signs, as we just saw, the Mewar painting depicts only

one: Dasharatha seated on a throne close to a woman in a blue sari brandishing a stick. The king’s

countenance does not betray his altered state nor his passage into the afterlife.

Intriguingly, while the corresponding text mentions women in two places, the visual represen-

tation is undoubtedly a painterly response, independent of the text. According to Hirananda’s

text (appearing on f.83v): “Dark red-brown [krsnapingala] women were laughing at the king,

who was seated on a throne of black iron and wearing black clothes.”10 Nowhere does the text

suggest that the women were physically violent toward Dasharatha. Clearly, image and text

316

� Dasharatha’s Oil Vat in the Mewar Ramayana

Figure 24.2 �

Bharata’s Dream, Folio from Jagat Singh’s Ramayana (f.83R), Mewar, ca. 1650–1652, water-

color on paper. Courtesy of The British Library Add. MS 15296(1).

pursue separate paths. The text speaks of women, whereas the painting shows a single woman

gesticulating with a stick. The painting renders Dasharatha in royal garb, dressed in a red jama,

necklaces, earrings, cummerbund, and crown—not in somber black as the text would have it.

The other textual reference to a woman occurs prior to this scene and involves Dasharatha being

dragged towards the south by men and a single woman. That vision too bears no relation to the

visual depiction.

There can be little doubt that text and image adopt divergent attitudes towards Dasharatha’s post-

mortem oil immersion. While visual artists allocated a small fraction of a single painted surface to the

event, the text dwells on images of Dasharatha’s submersion, particularly in Bharata’s dreams. And

while those dreams receive vivid treatment in textual form, they take on an unexpected turn visually,

with just the single bizarre scene between the woman and Dasharatha receiving attention. These

text-image slippages raise many questions, not least of which is the ever-relevant question about

reception. Questions about makers’ visual tactics for enlivening the epic are just as relevant, as are

questions about the relationship between visual representations and contemporary funerary practices.

That is, could painters have been drawing from their immediate western Indian material environment

to give form to Dasharatha’s droni and the other death rites depicted in this painted book?

Another contemporaneous depiction of the oil vessel included in a Ramayana manuscript made

in the last part of the sixteenth century for the Mughal courtier Abd al-Rahim Khan-i-Khanan

(1556–1626) may illuminate some of these questions. Dasharatha’s droni takes centerstage in

the Mughal painting in a striking monoscenic image (Figure 24.3). What’s fascinating about

this droni scene is its marked difference from the Mewar painting: unlike Mewar, painters array

Bharata, Shatrughna, and Dasharatha’s ministers around the droni, and moreover, the figures

actively engage with the vessel. This droni has a substantial presence besides. Let me press the

point even further. In the Mughal paintings, mourners touch Dasharatha’s corpse as opposed to

in Mewari images, where contact is conspicuously absent. To be sure, Mewari painters depicted

Dasharatha on his death bed: attired in sumptuous yellow, surrounded by the distressed court

women who nudge his head, shoulders, and hands to wake him (Figure 24.4). But the only

glimpses of Dasharatha thereafter are in the small droni scene with which I began the chapter

317

� Subhashini Kaligotla

Figure 24.3 �

Dasharatha’s Droni, Folio from Rahim’s Ramayana (f.102b), 1597–1605, Mughal India, ink,

opaque watercolor and gold on paper. Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington,

D.C.: Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1907.271.173–346.

318

� Dasharatha’s Oil Vat in the Mewar Ramayana

Figure 24.4 �

Dasharatha’s Death, Folio from Jagat Singh’s Ramayana (f.80R), Mewar, ca. 1650–1652,

watercolor on paper. Courtesy of The British Library Add. MS 15296(1).

and in the cremation scene which I will discuss presently. The important point, however, is that

Mewari painters did not show the princes or ministers interacting with Dasharatha after his oil

submersion even though this is mentioned in the Valmiki text and included in the Mewar manu-

script.11 The droni scene is not only small but also compressed with two larger court scenes, and

the king is noticeably alone, except for the two attendants. He is visualized from the neck up, in

strict profile, as if depicted on a coin (Figure 24.1). The attendants fan his body, but do not handle

it. Their presence is analogous to the fly whisk bearers who accompany royal and divine figures

in premodern painting and sculpture—a necessary trope meant to highlight the central figure’s

venerable status.

Here is the Mughal droni painting by contrast. An aerial view of Vasishtha, Bharata, Shatrughna,

and six courtiers, the image is a poignant portrait of grief. Heads drooping like wilted flowers, the

princes approach their father’s oily coffin. Closest to the vessel, Vasishtha plunges his hands in

the oil, ready to retrieve Dasharatha now that Bharata is home to perform the death rites.12 The

figures are organized into the bottom half of the vertically oriented painting. They stand within the

palace walls, in a garden dotted with flowers, and are boxed in by a domed pavilion on the right.

Directly above is a large block of text in Persian, the Mughal administrative language, into which

the Sanskrit Ramayana had been translated for the emperor Akbar (1542–1605) and about which

I will have more to say. A pretty landscape constituted of pink rocks, bird-pairs in a blue sky, and

a distant palace make up the very top band of the picture plane. The vessel is large, taller than

Vasishtha’s waist, and resembles a decorative jar with a scrolling floral design across the top and

bottom. All except two figures look toward it.

While Mewari makers show Dasharatha’s head peeking from the droni, Mughal artists take a

more playful approach. The lower half of Vasishtha’s body is obscured by the droni, presumably

because he is leaning against it. Moreover, his hands have disappeared into the oil. And now this

rather delightful detail: a hand—palm forward, fingers splayed—is visible at the vessel’s rim.

Whose hand could it be? It doesn’t look as if it quite belongs with Vasishtha’s wrist. The inscrip-

tion on the cremation folio (f.103b) answers the question. The hand belongs to Dasharatha not

Vasishtha!13 It seems painters couldn’t resist showing the dead king reaching towards his son from

319

� Subhashini Kaligotla

the other world. The significant point is that both Mughal and Mewari visual artists have taken

creative liberties within the broader narrative framework offered by the Ramayana. They inserted

details absent from the text (Mughal) or else emphasized details that are negligible (Mewar).

Dasharatha’s cremation scene in the same Mughal manuscript is even more concerned with his

physical body (Figure 24.5). The king’s pyre forms the apex of this arresting painting, which is

also vertically organized in keeping with the conventions of Mughal manuscripts. The enshrouded

body lies on a lattice pattern of wood, tilted upward to give viewers a full impression of the cre-

mation. Braids of fire and smoke issue forth to consume the king’s body, which is encased by

a flaming orange oval. Crucially, the king is not laid directly on the pyre but on the laps of two

women, one cradling his crowned head and the other his calves and feet. Both ladies lean tenderly

toward him, extending their arms in an embrace. To be clear: the women are on the pyre with the

king, whose entire body is visible, as is his crowned head. Here then is another detail absent from

the text. For nowhere in the Valmiki Ramayana’s description of Dasharatha’s cremation is there

even a hint of widow immolation; the king’s wives circumambulate the pyre, as do the princes,

priests, and others, but they do not sit with the king on the burning pyre.14 An anthropomorphized

sun with eyes, nose, and mouth observes from the painting’s top right—a further echo of the fire

eating the dead king and his widows. In the remaining two thirds of the picture plane are other

mourners, including a fainting Bharata and many more of the king’s visibly grieving women.

The Mewar analogue of this scene is far more sedate in comparison (Figure 24.6). One obvious

difference is its treatment of Dasharatha’s pyre, shown in the painting’s bottom-left quadrant,

surrounded by the two princes and other males. Though the rising flames are high, there is little

indication of Dasharatha’s physical presence, merely dashes of white for the shroud. And while the

painting also includes Dasharatha’s bier as it makes its way to the cremation ground, there too only

the head is visible in its numismatic profile, recognizable from the earlier droni scene. Importantly,

no one touches Dasharatha. Thus, if the Mughal painting is concerned with documenting con-

temporary social practices such as widow immolation—which are also noted in the Annals of

Akbar (Ain-i-Akbari) text—and in the dramatic potential of the scene’s emotional outpouring, then

Mewar seems much more interested in representing the somber, respectful, and socially correct

attitude expected during a monarch’s funeral. Mewari painters are careful, for instance, to include

specific funerary rituals such as the udakam—the libation ritual for the dead, which takes place

only once the body has been burnt. Notice the kneeling princes, against a mauve background in the

painting’s bottom right quadrant, pouring water for their father while their mothers and the court

ladies look on.

It is tempting to ask whether these differences between the two Ramayana manuscripts hint at

variant attitudes toward Dasharatha’s physical body after death and suggest more broadly varying

agendas for making and even viewing such painted books.

It’s time to return to the chapter’s central interest: the Mewar Ramayana’s portrayal of Dasharatha’s

postmortem body. While the accompanying text informs us of both the king’s submersion in the

oil vat and the retrieval of his body, the paintings allocate a tiny space to the oil vat, where, for all

intents and purposes, the king is alone and untouched. Furthermore, if the text’s vivid descriptions

of Bharata’s dreams evoke the king’s ignominious oil and dung bath, then the painterly analogue

features him in a pose of relative ease seated on a blue platform. The painting does not deny the

king’s death. However, neither his countenance nor his attitude betrays the distress and indignity

he suffers in his son’s dreams. If artists have made any concession to the prince’s visions, it is with

respect to dress. For in the dream-picture, and only in that picture, Dasharatha appears in a red

jama. In the rest of the paintings, he is attired in a translucent white jama or a yellow dhoti.

320

� Dasharatha’s Oil Vat in the Mewar Ramayana

Figure 24.5 �

Dasharatha’s Cremation, Folio from Rahim’s Ramayana (f.103b), 1597–1605, Mughal India,

ink, opaque watercolor and gold on paper. Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution,

Washington, D.C.: Gift of Charles Lang Freer, F1907.271.173–346.

Is it possible that these divergences between image and text have to do with the challenges

Bharata’s dreams posed to Mewari painters? That is, were artists hampered by space issues or tech-

nical constraints? I believe the answer is a decisive no. It is worth remembering that the paintings

in Mewar’s Ayodhya Book—68 in total, finished between 1648 and 1652—are sophisticated

321

� Subhashini Kaligotla

Figure 24.6 �

Dasharatha’s Death Rites, Folio from Jagat Singh’s Ramayana (f.93R), Mewar, ca. 1650–1652,

watercolor on paper. Courtesy of The British Library Add. MS 15296(1).

compositions.15 Many deftly encompass multiple Ramayana episodes, with painters using innova-

tive pictorial strategies such as multiplication of figures and the stacking and segmenting of

space to depict multiple temporalities in a compact visual field.16 One painting repeats the figures

of Rama, Bharata, and Shatrughna seven times to convey seven discrete points in space and

time (f.114r). Importantly, we can attribute the book to the workshop of master painter Sahibdin

(c. 1620–55) who had by then solidified his reputation and distinctive painting style through a

slew of earlier commissions. Which is to say, the evidence of the book argues for painters’ facility

with their subject matter: they could have represented Bharata’s dreams more fully, including the

king’s various postmortem debasements, if they had intended to do so. No doubt, the parallel text

was not shy about doing so. That they did not, confirms kingship as an indisputable emphasis of

the Mewar Ramayana, particularly of this book, and the imperative to depict the honors due to the

king despite the situation.

It is the office of kingship, regardless of who held it, that visual artists were at pains to esteem—

a pattern that is clearly discernible in the portraits of sovereigns and sovereignty throughout. Take

the sumptuous court scenes that open and close the book (f.2r and f.129r). In both, the throne

under a fulsome parasol, the parasol being one of the preeminent and enduring symbols of Indic

kingship, is set off in a red, proscenium-like space. The Kosalan court is assembled around it. The

key difference between the two images is that Dasharatha sits on the throne in the opening image

whereas Rama’s sandals occupy the seat in the latter. Thus, the book opens on the still living patri-

arch and closes after Rama’s departure for the forest and Dasharatha’s death. Since loyal Bharata

considers the exiled Rama the rightful ruler, the sandals in the last picture, as Rama’s indices, sym-

bolize his sovereignty and the continuation of righteous governance. Moreover, here is Bharata

on the left, dressed as an ascetic holding up the parasol, while Shatrughna waves the fly whisk.

Kingship, then, rarely makes a public appearance without its appropriate visual markers—the

parasol, flanking flywhisk bearers, and the crown and other ornaments. And artists remain solici-

tous throughout of Dasharatha’s appearance—no, of the king’s appearance. In court scenes, he is

seated cross-legged, dressed in the fine, white jama I alluded to earlier: his crowned head shown

in strict profile while the bejeweled body is rotated in full view of the court (and the viewer). Not

only do artists approach Dasharatha in this way but also his peer, the king of Kekaya, Bharata’s

322

� Dasharatha’s Oil Vat in the Mewar Ramayana

grandfather. Indeed, the two kings are indistinguishable from one another in dress, ornamentation,

facial features, and bearing; only context helps us tell them apart (compare Dasharatha in f.2r with

Kekaya in f.6r). Their jharokha or balcony portraits are also identical: the kings are simply mirror

images of one another (compare Kekaya’s portrait in f.4r with Dasharatha’s in f.13r). Most strik-

ingly, their flattened, hieratic profiles are eerily like Dasharatha’s profile in the droni and cremation

scenes.

The representation of Dasharatha in the oil vat—not to mention artists’ diffidence toward

the undignified dream scenarios—begins to make sense in light of this visual world’s aesthetic

commitments. The crucial point is that the droni image belongs to the family of kingship portraits

dispersed throughout the book, from throne scenes to jharokha portraits. The droni image is

thus a close kin of the closing picture, where the twin princes, Bharata and Shatrughna, like the

flywhisk bearers in the tiny droni scene, visually demarcate the central sign of kingship through

their reverences.

Thus, despite my continued interest in researching links between the droni scene and con-

temporary mortuary and material practices, I suspect that it was a stylized representation tucked

away in a corner to be faithful to the Ramayana narrative without calling undue attention to itself.

Nonetheless, future research might look for parallels in contemporaneous western Indian material

culture and the form, materials, and décor of the droni. Surviving metalware or representations of

objects in painting and other media may also provide further clues concerning these questions as

well as about techniques of production.

Conclusion

It is perhaps unremarkable that a painted Ramayana made for a western Indian ruler should

emphasize kingship as an overarching value, especially if that king’s Rajput clan claimed descent

from the divine Rama. Remarkable, however, is the sensitivity with which visual artists rendered

the death rites of the epic’s paterfamilias, charting an independent aesthetic path and illustrating

once again that the Ramayana was a flexible and fecund site of ekphrasis. A single scribe may

have written the text of the Mewar Ramayana, but teams of artists likely worked on each of the

Ramayana’s seven books. It is also likely that painters themselves worked out how to render

the scenes chosen for illustration even if the choices were made by a master painter. Moreover,

the distinct visual strategies of individual books suggest that a larger vision belonging to a master

such as Sahibdin prevailed. Possibly such an individual ensured the book’s overall vision and

remained attentive to the preoccupations of its elite audience.

Certainly, the choices of the Rahim Ramayana, whose droni and cremation scenes we also

examined, point to a different set of animating interests, though it would be a mistake to align

those differences merely along an insider versus outsider perspective on the epic. Of course, that

manuscript was a result of the large-scale translation projects Mughal emperor Akbar initiated

during the 1580s and 1590s for his Persianate court. And the translated texts included scores of

Indic literary, philosophical, religious, and political texts as well as the two great Sanskrit epics,

the Mahabharata and the Ramayana. The Rahim Ramayana was one among three illustrated

manuscripts produced after the Persian translation was complete in 1588.17 The most lavish of

these and the first in the series was made for the emperor himself and included 176 paintings.

While an in-depth analysis of those manuscripts is well beyond the scope of this short chapter,

one insight into the translations may help situate the curious attitude of the Mughal droni image,

which is arguably less circumspect about the dead king’s mortal flesh. Audrey Truschke has

323

� Subhashini Kaligotla

written about Mughal elites’ fascination with the fantastical elements of Indic texts, specifically

the Mahabharata, which the emperor prized above all and had translated before the Ramayana

(Culture of Encounters).18 Truschke makes a persuasive argument that not only the translators

but also the visual artists who worked on illuminating the Mahabharata (Razmnama in Persian)

catered to the enduring and long-standing inclination of Islamicate courts toward wondrous stories

of oddities and marvels (aja’ib in Persian) (Truschke 109–110). Thus, Dasharatha’s droni—seen

from above, with the court as audience, and the dead king’s hand creeping out—must belong

within the category of strange tales and “extraordinary things” that Mughal elites found on almost

every page of books like the Mahabharata and the Ramayana. Wonder may in fact be a good

starting point in any future investigation of the connection between such early modern painted

images of Dasharatha’s oil vat and the coeval material culture.

Notes

1 For the dates of composition, authorship, and other questions about the Ramayana’s historicity, see

Goldman’s excellent introduction.

2 I have relied on Losty’s analysis of the Mewar book for the factual details cited here (“The Mewar

Rāmāyaṇa Manuscripts” 17).

3 See Brockington’s essay, “The Textual Evidence of the Mewar Rāmāyaṇa manuscripts,” for the visual

qualities of the Mewar Ramayana’s text, and for an analysis of the narrative’s progress in textual form

and how that corresponds with its visual progress.

4 I am grateful to Phyllis Granoff for deciphering and translating the Sanskrit text on folio 83v cited in this

essay.

5 The authoritative source on the subject is Kane’s History of Dharmaśāstra (233–234). Besides the

Ramayana, Kane cites the Viṣṇu Purāṇa, which mentions that the body of Nimi was covered in oil

and fragrant substances and therefore prevented from decomposing. Nimi’s body, importantly, “looked

as if death was recent.” In addition, the Vaikhānasa Śrautasūtra and the Satyāṣāḍha Śrautasūtra also

mention the practice in relation to brahmins who die away from home and whose bodies must therefore

be preserved in a trough of sesame oil and brought home.

6 Another Buddhist text—a Pali story about the grief-anguished king Munda who wants to keep seeing his

dead wife Bhadda and so proposes to inter her in a taila droni—also affirms the use of the oil vat in early

India for postmortem conservation. The narrative appears in the Aṅguttaranikāya portion of the Sutta

Piṭaka and has been explored by a number of scholars in the broader context of ancient Indian mortuary

rituals. See Strong’s “The Buddha’s Funeral” (39) and von Hinüber’s “Cremated like a King: The Funeral

of the Buddha within the Ancient Indian Cultural Context” (46–47).

7 For an excellent account of the timeline of the Buddha’s funeral as well as the diverse scholarly interpret-

ations of the available sources, see Strong, pp. 32–59.

8 Strong, p. 38.

9 This is not all that different from the Viṣṇu Purāṇa’s characterization of the body of Nimi, cited earlier.

See note 5.

10 Once again, I have relied on Granoff’s translation.

11 For instance, in the critical edition of the Valmiki Ramayana, it is Bharata who takes the body of

Dasharatha and places it on a bed and adorns it while attendants place it on a bier. Notably, in the text

included in the Mewar Ramayana on f.93v, Bharata places the body on the bier, adorns it, and carries

the bier together with Shatrughna. Here, too, I am indebted to Granoff’s analysis of several Ramayana

recensions and the Mewar text.

12 Note that in the critical edition of the Ramayana it is unclear who removes the body of Dasharatha from

the oil vat. There’s no doubt of course that it was done. See Rām.II.70, 4–5. Thus, again, we see the

agency and creativity of visual artists at work in giving visual form to this key scene.

13 I thank Mohit Manohar for reading the corresponding Persian, and for verifying that the text confirms that

it was Dasharatha who was being pulled out of the oil vat by the hand.

14 See Rām.II.70, 19–22 for the participation of the women at the cremation.

15 Dehejia gives a date range (324); Topsfield by contrast dates the Ayodhya book to 1650 (72).

324

� Dasharatha’s Oil Vat in the Mewar Ramayana

16 See Dehejia for Sahibdin’s synoptic narrative strategies and Topsfield for an analysis of such visual strat-

egies as segmentation and stacking.

17 The three Ramayanas, in the order of their creation, are: emperor Akbar’s manuscript; the now dispersed

manuscript of the Queen Mother Hamida Banu Begum; and Abd al-Rahim’s Ramayana. Of these, the

first, held by the Maharaja Sawai Man Singh II Museum of Jaipur, has remained inaccessible to scholars

and so has been little studied. For monographic treatments of the last two books, see Seyller, Sardar,

and Truschke’s The Ramayana of Hamida Banu Begum, Queen Mother of Mughal India and Seyller’s

Workshop and Patron in Mughal India: the Freer Rāmāyaṇa and other Illustrated Manuscripts of ʻAbd

al-Raḥīm.

18 See chapter three for Akbar’s special interest in the Mahabharata (102).

Works Cited

Brockington, J. L. “The Textual Evidence of the Mewar Rāmāyaṇa manuscripts.” https://www.bl.uk/

onlinegallery/whatson/exhibitions/ramayana/pdf/mewar_ramayana_textual_evidence.pdf. Accessed

1 September 2022.

Dehejia, Vidya. “The Treatment of Narrative in Jagat Singh’s Rāmāyaṇa: A Preliminary Study.” Artibus

Asiae, vol. 56, no. 3/4, 1996, pp. 303–324.

Goldman, Robert P. “History and Historicity.” The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki: An Epic of Ancient India, vol. 1,

Bālakāṇḍa, edited by Robert P. Goldman, Princeton University Press, 1984, pp. 14–59.

Kaligotla, Subhashini. “Words and Pictures: Rāmāyaṇa Traditions and the Art of Ekphrasis.” Religions,

vol. 11, no. 7, p. 364. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11070364. Accessed 8 August 2022.

Kane, P. V. History of Dharmaśāstra, vol. 5. Bhandarkar Oriental Institute, 1930–1962.

Losty, J. P. “The Mewar Rāmāyaṇa Manuscripts.” https://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/whatson/exhibitions/

ramayana/pdf/mewar_ramayana_manuscripts.pdf. Accessed 1 September 2022.

Pollock, Sheldon I, translator. The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki: An Epic of Ancient India, vol. 2, Ayodhyakāṇḍa,

Princeton University Press, 1986.

———. “Rāmāyaṇa and Political Imagination in India.” Journal of Asian Studies, vol. 52, no. 2, May 1993,

pp. 261–297.

Ramanujan, A. K. “Three Hundred Rāmāyaṇas: Five Examples and Three Thoughts on Translation.” The

Collected Essays of A. K. Ramanujan, edited by Vinay Dharwardker, Oxford University Press, 1999,

pp. 131–160.

Seyller, John, Marika Sardar, and Audrey Truschke. The Ramayana of Hamida Banu Begum, Queen

Mother of Mughal India. Museum of Islamic Art: Qatar Museums; Cinisello Balsamo, Milano: Silvana

editoriale, 2020.

Seyller, John. Workshop and Patron in Mughal India: the Freer Rāmāyaṇa and other Illustrated Manuscripts

of ʻAbd al-Raḥīm. Artibus Asiae Publishers: Museum Rietberg in association with the Freer Gallery of Art,

Smithsonian Institution, 1999.

Strong, John. “The Buddha’s Funeral.” The Buddhist Dead, edited by Bryan J. Cuevas and Jacqueline I.

Stone, University of Hawai’i Press, 2007, pp. 32–59.

Topsfield, Andrew. Court Painting at Udaipur: Art under the Patronage of the Maharanas of Mewar. Artibus

Asiae Publishers and Museum Rietberg, 2002.

Truschke, Audrey. Culture of Encounters. Columbia University Press, 2016.

von Hinüber, Oskar. “Cremated like a King: The Funeral of the Buddha within the Ancient Indian Cultural

Context.” Journal of the International College for Postgraduate Buddhist Studies, vol. 13, 2009, pp. 33–66.

325

�

Subhashini Kaligotla

Subhashini Kaligotla