Iranian Journal of Sociology, 2008, 2 (1): 190-227

Gender Differences in Health-related Knowledge and Beliefs and their

Relationships with Health-related Behaviors

Mohammad Esmaeil Riahi: Assistant Professor- University of Mazandaran

Abstract

Objectives: The main objectives of this study are to describe and explain gender & national differences

in health related knowledge & beliefs, and their impacts on health behaviors of university students in Iran

(Mazandaran University) and India (Panjab University), with special emphasis on psychosocial factors.

Methods: Survey method is been used for conducting the present study. By means of multi– stage

sampling procedure, 504 students from both the universities have been selected randomly, to fill up the

self- administered questionnaire consists of two scales regarding health related knowledge & beliefs ,and

some questions about health-related behaviors such as personal hygiene , physical exercise , dietary

habits , preventive medical checkups, alcohol consumption, and smoking.

Results: The main findings of the present study can be summarized as follows: 1) The university

students in India compared with their counterparts in Iran were more aware of risk factors involved in

certain diseases (higher rates of health knowledge), while men and women students did not differ in this

respect. 2) The university students in both countries were not different in terms of health beliefs, while

women compared with men students were more conscious of the importance of certain behaviors for

health maintenance (higher rates of health beliefs). 3) Association between health knowledge and healthrelated behaviors was found to be weak and non significant; while a very strong and significant

association between health beliefs and health related behaviors was observed.

Discussion: Improving health beliefs of students rather than their health knowledge, is an essential step

in order to increase their positive health-related behaviors.

Keywords: Gender, Gender differences, health knowledge, health beliefs, health behaviors, University

students, Iran, India

1) Introduction

Health is one of the most vital but taken-for granted qualities of everyday life.

There is good evidence that health is a major basis of human progress and that lack of

it, is one of the predisposing factors of national decay. As Cockerham (1989: 2) rightly

points out: while a person’s social class, income, and access to goods and services are

highly important, the quality of one’s life, ultimately depends upon one’s level of health.”

In light of the role of health in happiness, efficiency, and well-being, it seems that every

social group and society strive for the betterment of health of its members.

1

�Overall, the most important determinants of the health status can be summarized as

follows: heredity and genetic composition; socio-demographic characteristics (such as

age, marital status, place of residence, etc.); socio-economic status (such as education,

income, and employment); Socio-cultural factors (gender, religion, ethnicity); gender

inequality; health knowledge and health beliefs; health-related behaviors (such as

smoking, alcohol consumption, physical exercise, and dietary habits); political economy;

poverty and malnutrition; access to health services and facilities; and physical

environment. A combination of factors than just one of them determines the health

status of individuals and societies. Among the above mentioned factors, this study

focuses on health knowledge and beliefs and their impacts on the health behaviors.

The literature on associated factors with health beliefs and knowledge identified some

psychosocial factors. For instance, Weissfeld and colleagues (1990) found that sociodemographic markers of social disadvantage (e.g., black race, or low SES) appeared to

associate with favorable health beliefs, that is, with health beliefs often associated with

health promoting behaviors. They, specifically, found that blacks expressed greater

concern about health (health concern). Significant gender, ethnic, and acculturation

differences were found among beliefs related to frequency of condom use in the past

year by Norris and others (1994) in Midwest (USA). A cross-cultural study of beliefs

about smoking among teenaged females by Hanson (1999) also showed that beliefs

related to attitudes about smoking differed among three ethnic groups. The findings of

this study suggested that specific beliefs distinguish between smokers and nonsmokers

and that some beliefs differ by ethnicity. Jobanputra and Furnham (2005) studying the

cultural differences in beliefs about health and illness found that Gujarati Indian

immigrants agreed with items reflecting supernatural explanations of ill health more than

indigenous British Caucasian participants. Awasthi and colleagues (2006) conducted a

study on health beliefs of cervix cancer patients and found that individual and

psychosocial causes were more strongly represented in the belief system of patients

than environmental or supernatural causes. Additionally, Munro and others (2007) in

assessing the impact of training on mental health nurses’ therapeutic knowledge found

a significant group effect on knowledge about co-morbidity. The training programme

was effective in improving participants’ knowledge of alcohol, drugs, and co-morbidity.

Likewise, Bassey et. al (2007) found gender differences in health knowledge about HIV.

2

�Accordingly, they identified a great disparity between male (73.7%) and female (28.9%)

respondents on knowledge about HIV.

On the other hand, many studies have been conducted to find out associations

between health knowledge and beliefs with health-related behaviours. A brief review of

literature in this respect shows that findings of studies conducted on health knowledge

in relation to health-related behaviours (HRBs) were not consistent and stable, but

health beliefs had a strong and consistent relationship with health-related behaviors. For

example, a few studies highlighted how health knowledge is related to decrease in

health risk behaviors (Dittmar et al. 1980), and an increase in health-promoting

behaviors (Fleetwood and Packa, 1991). It also influences dietary behavior (Harnack et

al., 1997); and or brings about reduction in alcohol consumption, improvement of

physical activity (Wardle and Steptoe, 1991), and treatment-seeking behaviour by

women reported depression symptoms (Simmons et. Al, 2007). Despite of these

supportive evidences regarding influence of health knowledge on HRBs, however, some

research findings point out that mere information of the hazards of health risk behaviors

is not a sufficient condition for the avoidance of risk-taking behaviors. For example, no

relationship could be found between health knowledge and reduction in smoking

(Wardle, 1992; Jones et. al., 1992; Small, 1994; Steptoe & Wardle, 1992; Kapoor et al.,

1995; Yassin et al., 1998; Kurtz et al, 1972); or alcohol consumption (Steptoe and

Wardle, 1992). Further, according to Lopez et al. (1992) there exist many contradictions

between the theoretical acquisition of health knowledge and the observed frequency of

high-risk behaviors. Similarly, Avis et al. (1990) concluded that knowledge does not lead

to risk reducing behavior in cardiovascular diseases as well as sun-protective

behaviors.

However, majority of the studies on health beliefs confirmed the positive relationship

between health beliefs and health behaviors. Rather, it has been observed that unlike

health knowledge, there has been a constant relationship between health beliefs and

health behaviors. According to Monneuse et al. (1997) knowledge of the significance of

behaviour seems to be closely associated with health related behaviors. Similarly,

Steptoe and Wardle (1992) come to the conclusion that health beliefs consistently

showed a positive association with health practices. Cody and Lee (1990) consider

health beliefs as a significant variable in predicting health behaviors. Calan

3

�and Rutter (1988) also show that a change in the health beliefs could result in the

improvement of health behaviors. Thus, the above studies show that people’s beliefs on

health matters have an important effect on what they do about health, namely; their

health behavior. Abroms and colleagues (2003) also concluded that males and females

differed in their beliefs that motivated their sunscreen use. Holt and others (2003) in the

studying association between spirituality, breast cancer beliefs and mammography

utilization among African American found that the belief dimension of spirituality played

a more important role in adaptive breast cancer beliefs and mammography utilization

that did the behavioural dimension. A research done by Riley-Doucet (2005) showed

that family dyads with beliefs that pain was controllable had less symptom distress than

dyads with beliefs that pain was not controllable. Moreover, Lee and colleagues (2007)

revealed that the fear-avoidance beliefs factor is an important biopsychosocial variable

in predicting future disability level and return to complete work capacity in patients with

neck pain.

Increasing attention has been paid over the last two or three decades to the

contribution of behaviors to health. Today, many of the major health problems, such as

heart disease and cancer, are seen as attributable to individual behavior patterns

(Macintyre, 1986: 407). The prevalence of chronic diseases is showing an upward trend

almost all over the world, including the developing countries, because of shifting of

patterns of disease in these countries. People in the developing countries, especially

the middle and high social classes, are exposed to chronic, non-communicable

diseases attributable to health related behaviors. Therefore, it is the right time that the

developing countries increase the awareness of their population about health risk

behaviors (to increase health knowledge and to improve health beliefs) and take

appropriate steps; to avoid the onset of epidemic form of non-communicable diseases

that are likely to emerge in a big way as the status of these societies improves.

Although different social and cultural factors such as income, employment, education,

age, ethnicity, and class have been found to play an important role in the construction of

differences in terms of health-related knowledge, beliefs, and behaviors, but it can be

presumed that gender is one of the most important factors influencing health related

behaviors in each social group as well as society. Accordingly, in the past three

decades, the issue of gender differences in health and illness has gained popularity as

4

�a subject of research among social scientists. The survey of literature on gender

differences on health status of different societies reveals that women suffer more from

disease in their lifetime, but men die early; women live longer, yet they seem to be

sicker. Further, many research studies found that in general, women are more likely

than men to adopt healthier habits and perform positive health behaviors.

Overall, the main problem that this study is trying to focus on is to understand the nature

of variations in health related knowledge and beliefs of university students and their

associations with health related behaviors. This study has attempted a twofold

comparison in health related knowledge, beliefs and behaviors, that is, by gender and

nationality at the same time. It tries to find out how far health related knowledge and

beliefs of male and female university students in Mazandaran University (Iran) and

Panjab University (India) differ and which factors affect these differences? In the other

words, in this study, gender differences in health related knowledge and beliefs of

university students in Iran and India were described and explained by means of several

socio-psychological and cultural factors. Therefore, the main questions which this study

tries to answer are:

- Are there any gender differences in health-related knowledge and beliefs of university

students in the total sample as well as within each university context?

- What are the associated factors, which influence these differences?

- And how far health knowledge and beliefs act as positive predictors of health related

behaviors?

2) Theoretical Framework

The study of gender differences in health/illness has been approached from a

number of perspectives. In general, these perspectives can be broadly put into two,

namely: Biomedical and Socio-medical. According to the Biomedical perspective it is

hypothesized that observed gender differences in health are the product of biologically

based inherited risks (Kandrack, 1991: 579). In the biomedical model state of health is a

biological fact (immutable, real, independent) and ill health is caused by biological

calamities (Moon and Gillespie, 1996: 83). The Socio-medical perspective on the other

hand, hypothesizes that gender differences in health can be explained in terms of social

and cultural factors (Kandrack, 1991, 579). The Socio-medical model looks at state of

5

�health as socially constructed, varied, uncertain, and diverse. It considers social factors

as the causes of ill health, which can be identified through beliefs, and interpretations

built upon custom and social constraints (Moon and Gillespie, 1996: 183).

The present study makes use of the socio-medical perspective to explain gender

differences in health related knowledge, beliefs and behaviors of university students in

Iran and India. Within the broad framework of the socio-medical approach, there are

several approaches such as socialization theory, social role theory, and social position

and socio-economic status.

2-1) Socialization Theories

Socialization is the complex learning process through which individuals develop

selfhood and acquire the knowledge, skills, and motivation required for participation in

social life (Mackie, 1990: 61). In socialization theory, some social groups or

organizations such as family, peer groups, school, and mass media are considered as

agents of socialization. Family socialization forms the basis of many of our health beliefs

and behaviors. Many parents attempt to provide a healthy role model. This may lead to

health enhancing behavioral change by parents. Maintenance of health damaging

behavior may also result from the pressure of parenthood, particularly where material

circumstances are poor and resources are low. Even family related life events may

contribute more positively to lifestyle change (Penny et al., 1994: 113-4). Overall, the

family system plays a major role in children’s learning of health related knowledge,

beliefs, and behaviors. From amongst the different socialization theories, two most

important ones have been explained briefly below:

2-1-1) Social Learning theory

Social learning theory, which has been most substantially articulated by Bandura

(1977, 1986), emphasizes the notion that behaviors are gradually acquired and shaped

as a response to the positive and negative consequences of those behaviors. In

summary, social learning theorists argue that gender role behaviors, are learned by

reinforcement (rewards and punishments) and observational learning. Children are

rewarded or punished by their parents and society for exhibition behaviors appropriate

to their gender role. As a result, gender-appropriate behaviors take on greater value for

the child and are exhibited with greater frequency (Eccles, 2000: 455). Social learning

6

�theory places more emphasis on environmental influences. Accordingly, health

promotion or risk behaviors are socially learned and purposeful behavior, results from

interplay of social–environmental and personal perceptions and influences. For example,

this theory conceptualizes that alcohol use as a socially learned, purposive, and

functional behavior results from the interplay between socio-environmental factors and

personal perceptions (Gonzalez, 2000: 4). In this regard, parents may influence their

children’s drinking through both direct modeling of alcohol use and the transmission of

parental values about drinking (Jung, 2001: 164). In the study of health related

behaviors, social learning theory as a cognitive view emphasizes expectancies that we

form about the positive/negative effects of each health related behavior. For example, to

have a belief in medical check up, one has to first learn the social norms regarding the

beliefs of others about it. Thereafter, one looks at the situation in which the check up

affects the health of the individual. Thus, one learns the effects of regular medical check

up through his/her health status.

2-1-2) Health Locus of Control

The construction of health locus of control was derived from the social learning

theory developed by Rotter in 1966. From this theory, Rotter developed the locus of

control construct, consisting of internal-external rating scale (www.med.usf.edu). The

locus of control construct refers to the degree to which an individual believes the

occurrence of reinforcements is contingent on his/her own behavior. Theoretical basis of

locus of control relies on individual differences between how people perceive events as

a result of their own behavior or endurance characteristics (internal), or as being

controlled by some other variables like chance, luck, fate, or authority (external).

Health locus of control is “a concept that refers to an individual’s views regarding the

relative control he/she has over his/her health condition (Pacther et al, 2000:716).

Externals refer to the belief that one’s health condition is under the control of powerful

others, or is determined by fate, luck, or chance, but internals refer to the belief that

one’s health condition is directly the result of one’s behavior. Internals are prone to

obtain

proper

nutrition,

exercise,

rest,

stress

reduction,

and

to

adopt

prevention/enhancement strategies to maintain/improve the state of their health.

External individuals are liable to exhibit behaviors, which are less action-oriented, and

appropriate response to the state of their health may not occur (www. members. tripod. com).

7

�2-2) Social Role Theory (SRT)

Social role theory focuses on studies of learned behavior of men and women in

society by means of their social and gender roles. Gender role theory derives from the

general concept of social role. It refers to the shared expectations that apply to persons

who occupy a certain social position as members of a particular social category. In this

manner, gender roles are those shared expectations that apply to individuals on the

basis of their socially identified sex. Accordingly, people hold expectations about the

behaviors that are appropriate to an individual because they identify the person as a

member of the social category that consists of either females or males (Eagly, 2000:

448). In the area of health and illness, social role theory attempts to understand how the

multifaceted nature of men and women’s lifestyle affects their health and well being

(Pavalko and Woodbury, 2000). According to Nathanson (1975) women report more

illness than men because it is culturally more acceptable from them to be ill; and the

sick role is relatively compatible with women’s other role responsibilities, and

incompatible with those of men, and also women’s assigned social roles are more

stressful than those of men; consequently women experience more illness. Gove (1984)

develops the ‘fixed role’ hypothesis and its relationship to men’s health. According to

this idea the roles of men tend to be more structured or fixed than the roles of women. It

is argued that highly structured or fixed roles tend to be causally related to good mental

health and low rates of morbidity. Gender differences in health knowledge, beliefs, and

behaviors can be attributed to gender role socialization, gendered expectations and

obligations that determine appropriate or misappropriate behaviors for men and women,

and influence health status of individuals. A common explanation of the decline in sex

differences in smoking in western societies focuses on the consequences of gender

equality. Narrowing sex differences in smoking in times of increasing gender equality

and strengthening values of female independence, leads to the inference that the new

found freedom and higher status of women have prompted the undesirable behavior of

smoking (Pampel, 2001: 388).

2-3) Social position and socio-economic status

The influence of socio-economic status on health related knowledge, beliefs, and

behaviors have been well documented. Lower socio-economic status individuals have

lower level of knowledge about risk factors of diseases, they are not deeply believed to

8

�importance of healthy lifestyle on health status, and they participate in fewer positive

health behaviors; for example, exercise, maintaining healthy body weight and change

their negative health behavior such as smoking at a slower rate than higher socioeconomic status individuals. Recent research indicates that social location in status

hierarchies is an important conditioning factor for the allocation of resources,

opportunities, and constraints that influence knowledge, beliefs and behaviors related to

health (Crzywacz and Marks, 2001; 203). People in lower socio-economic strata tend to

be disadvantaged in a broad array of biomedical, environmental, behavioral, and

psychosocial risk factors for health, which mediates the relationship between socioeconomic position and health. House (2001: 134) also points out that socio-economic

status determines and shapes individual’s exposure to and experience of virtually all

known psychosocial, and many biomedical risk factors for health. Thus socio-economic

positions are originally fundamental causes that shape exposure to and experience of

most diseases and risk factors for health.

Overall, several social, psychological, and biological mechanisms have been

hypothesized to underlie the socio-economic status–health relationship. One set of

hypotheses centers on the ways that socio-economic status may influence health status

through its effect on shaping the individual’s day-to-day lifestyle and health-affecting

behaviors, such as diet, sleep, exercise, smoking, drinking, and drug use. Another

pathway through which socio-economic status and health are hypothesized to influence

each other is by way of socio-economic status differences in exposure to psychological

stress and distress. Another obvious way is through differences in occupational

conditions (Mulatu and Schooler, 2002: 23).

The present study, proposes to test the efficacy of all these approaches in explaining

gender related differences in health knowledge, beliefs, and behaviors of university

students in Iran and India.

3) Data and Methods

3-1) Survey Design

The universe of this study relates to formally enrolled university students in Iran and

India. For the present study, which is incidentally cross-national study, separate

9

�samples of university students were obtained from Mazandaran University (in north of

Iran, Babolsar) and Panjab University (in north of India, Chandigarh).

The ultimate nature of the sampling procedure resembles the multi-stage sampling

procedure. At the first stage, Mazandaran University in Iran and Panjab University in

India were selected. Then, various and as much as possible similar departments in

each university (Law, Sociology, Economics, Commerce and Management, Physical

Education, Languages, Humanities, History, Political Sciences, Psychology, Botany,

Mathematics, Physics, Chemistry, Biology, Geology, and Chemical Engineering) were

selected in the second stage, and at the final stage, the samples of study were chosen

randomly from the students of each department who were present in the classroom

when sampling was in operation. For the purpose of sampling, rough estimates of the

total student population in these universities were obtained. These estimates showed

that nearly 27915 students in all were enrolled in both the universities. Thereafter, it was

decided to limit the size of the sample to roughly 500 respondents from both the

universities and around 250 from each of them. In Mazandaran University the total size

of the sample was 263 representing 7.2% of the total population; and in Punjab

University the total size of the sample came to 241, after eliminating the incomplete

questionnaires, representing 7.6% of the total population of students.

3-2) Data Collection

Data collection was done when the classes were going on and all those students

who were attending the classes on those particular days were distributed the

questionnaires with the presumption that all students enrolled would be present in the

classroom. Thus, ensuring the randomness of the sample, classroom setting was also

considered ideal for approaching the students because the students could be explained

the purpose of the study, given instructions about filling the questionnaires, and since

the questionnaires were distributed after seeking the cooperation of the teachers and

the authorities, a good response rate was expected.

The main instrument of data collection used in this study was the self-administered

questionnaire, which was developed using a combination of questions derived from

previous research studies, particularly Wardle & Steptoe (1991), Steptoe & Wardle

(1992), Callaghan (1996), Ross & Wu (1995), Douglas et al (1997), Patrick et al (1997),

10

�Pietila et al (1995), and Fennell (1997). Then every effort was made to adopt these

questions within the cultural contexts of Iran and India. A total of 43 question items were

included, among which 16 items referred to socio-demographic characteristics; 19 items

related to health behaviors, and 6 items related to psychosocial variables (such as

health locus of control, health concern, etc.). Further, the health knowledge questions

were in a multiple choice format, with one correct answer for each question; while the

health beliefs index consisted of five-point Likert type items. Finally, this study used one

questionnaire in two languages due to the nature of the study population: a Persian

version was used in Iran, and an English version in India.

3-3) Methods of Data Analysis

Data were analysed by using the statistical package for social sciences (SPSS).

Reliability analysis was conducted for testing the reliability of scales and indices.

Internal consistency of these sections of the questionnaire was calculated by using

cronbach alpha techniques. Descriptive statistics was applied to portray the current

status of subjects in demographic and socio-cultural characteristics, as well as socioeconomic status of their families. Analytical statistics (Student’s t-test and one-way

analysis of variance, ANOVA) were used to assess gender and national differences in

health related knowledge and beliefs, and also to determine significant factors

associated with each health related knowledge and beliefs.

3-4) Operationalization of Variables

3-4-1) Health Knowledge

Researcher developed an index of health knowledge or risk awareness by

presenting a matrix of six health problems (heart diseases, lung cancer, breast cancer,

high blood pressure, hepatitis, and tuberculosis) and nine health related risk factors

(smoking, alcohol consumption, stress, adding extra salt to meals, consumption of extra

fat, drinking excess coffee, physical inactivity, consumption of polluted water, and

receiving blood). Subjects were asked to tick the appropriate box if they were of the

opinion that the health problem was influenced by the factor in question. The overall

reliability coefficient for knowledge test in the overall sample was .9116 suggesting very

high internal consistency of the test.

11

�3-4-2) Health Beliefs

It can be defined as the given importance of a series of behaviors for health

maintenance by in individuals. Subjects were asked to rate the importance of 16

behaviors for health maintenance on the index. Some of these 16 items were; brushing

teeth regularly, regular physical exercise, consuming fruit and green vegetables,

avoidance of extra salt, sugar, animal fat, alcohol, and smoking. Beliefs concerning the

importance of behaviors for health were assessed by summated scores obtained on

belief items for each subject. The overall reliability coefficient for the belief index for the

overall sample was .8640, indicating very high internal consistency of the index.

3-4-3) Health-related behaviors (HRBs)

HRBs are those activities, which perform by individual for maintenance and/or

improvement of his/her health status as well as prevent from onset of disease. An

important point is that HRBs are those performed at an asymptomatic stage. In the

present study, we focused on six health-related behaviors, namely; personal hygiene,

dietary habits, physical exercise, preventive medical checkup, smoking, and alcohol

consumption.

3-4-4) Health Related Behaviors (HRBs) of Family

In order to find out how far HRBs of respondents were influenced by current patterns of

HRBs in their families, respondents were asked to identify how many persons in their

families observe HRBs in the study, such as: exercising, healthy dietary habits, personal

hygiene, regular medical checkups, smoking, drinking, etc.

3-4-5) Multidimensional Health Locus of Control (MHLC)

The Multidimensional Health Locus of Control (MHLC) belief scale was used in this

study to measure beliefs about health behavior. Respondents were presented with a list

of statements designed to gauge their views about an individual’s ability to control

health matters. Health locus of control was assessed using the multidimensional health

locus of control scales devised by Wallston, Wallston, and De Vellis (1978), which

modified on 1998 by Wallston (www.Vanderbit.edu/nursing /kwallston/ mhlcscales .htm ).

The MHLC have shown adequate internal consistency in the previous studies (Steptoe

and Wardle, 2001). In this study it shows the internal consistency of .6592

12

�3-4-6) Health Concern

Health concern or value for health is the value that individuals place on health as a

priority in their lives. Research shows positive association between the value for health

with health related behaviors (Steptoe & Wardle, 2001), and tendency in quitting

smoking (Greenlund et al., 1997). This index was constructed by two items, including;

‘all things considered, good health is the most important thing to have’, and ‘I always

think about my health.

3-4-7) Socio-economic Status of Family

Socio-economic status was used here to refer to inequality in ranking regarding

education, income, and job positions of parents. In each country a three-item scale was

used for the qualification of the individual respondents on different levels of socioeconomic status. The scores allocated to educational status of parents, job position of

parents, and total monthly income of the family.

3-4-8) Socio-demographic Variables

These variables are measured on a nominal or categorical basis, simply by dividing

them into two or three groups, such as gender (0=male, 1=female), university

(0=Mazandaran University, 1= Panjab University), nativity (0=urban areas, 1=rural

areas), type of residence (0=with family, 1= far away from family), level of study

(0=undergraduate, 1= postgraduate).

3-5) Hypotheses

- There is a significant association between level of education and health knowledge.

- There is a significant association between type of residence and health knowledge.

- There is a significant association between socioeconomic status of family and health knowledge.

- There is a significant association between nationality and health knowledge.

- There is a significant association between nativity and health knowledge.

- There is a significant association between gender and health knowledge.

- There is a significant association between nativity and health beliefs.

- There is a significant association between gender and health beliefs.

13

�- There is a significant association between health concern and health beliefs.

- There is a significant association between health locus of control and health beliefs.

- There is a significant association between health behaviors of family and health beliefs.

- There is not significant association between health knowledge and health-related behaviors.

- There is significant association between health beliefs and health-related behaviors.

3-6) Theoretical Model

Level of Education (Undergraduate/Postgraduate)

Type of Residence (Staying or far away from Family)

Socioeconomic Status of Family

Health Knowledge

Nationality (Iranian/Indian)

Nativity (Urban/Rural)

Health Related Behaviors

Gender (Male/Female)

Health Concern

Health Beliefs

Health Locus of Control

Health behaviors of Family

4) Results

4-1) Health Knowledge

4-1-1) University Level Differences in Health Knowledge

The analysis of inter-university data shows some differences as can be seen from

table one. These differences have been calculated only for the correct answers. On the

whole, students of PU were more aware of risk factors involved in all six diseases listed

in table one than their counterparts in MU, particularly in relation to hepatitis,

tuberculosis, high blood pressure, and lung cancer. In fact, on all the diseases

mentioned in the table, PU students endorsed the right risk factors more often than the

MU students.

14

�Table 1) Distribution of Health Knowledge among the Students at Mazandaran

University (MU) and Panjab University (PU)(Percentage of correct answers)

Diseases (%)

Risk

Factors

Heart

Lung

Breast

High blood

disease

cancer

cancer

pressure

Average

Hepatitis

Knowledge

TB

MU

PU

MU

PU

MU

PU

MU

PU

MU

PU

MU

PU

MU

PU

Smoking

92.0

75.9

96.0

93.3

59.1

36.7

53.2

60.0

9.4

56.6

29.7

47.1

56.6

61.6

Alcohol

consumption

60.4

78.6

17.9

27.8

14.6

18.9

51.5

84.8

10.4

50.9

6.8

22.5

26.9

47.2

Stress

92.2

87.9

33.5

63.3

41.4

35.6

85.5

96.1

17.5

60.0

23.9

49.5

49.0

65.4

Extra salt

48.9

49.0

32.9

54.1

30.8

56.1

78.1

88.2

16.3

52.3

23.5

49.6

38.4

58.2

Excessive

coffee

37.2

44.2

20.2

35.3

21.6

33.3

16.0

69.4

13.1

43.4

18.7

42.1

16.4

44.6

Animal fat

67.9

79.4

26.5

40.8

11.2

12.3

54.4

65.5

16.6

31.7

22.2

41.4

33.1

45.2

Polluted water

26.2

36.5

18.4

28.3

19.9

42.1

24.1

40.0

31.7

70.2

5.8

15.6

21.0

39.7

Receiving

blood

25.5

36.2

25.1

40.2

21.6

40.5

16.8

33.0

37.3

57.1

24.5

27.9

25.1

39.1

Physical

inactivity

87.3

71.8

25.1

40.5

24.9

40.2

64.2

55.2

20.1

39.7

23.9

31.5

40.9

46.5

Average

knowledge

59.7

62.1

32.8

47.1

30.6

35.1

49.3

65.7

19.2

51.4

19.9

36.3

35.3

49.6

To find out how far these university level differences in health knowledge were

significant, ‘Student’s t-test’ was applied.

Table2) University Level Differences in Health Knowledge

Awareness

of risk

factors for

illness

Mazandaran University

Panjab University

TN

Mean

value

Std.

Deviation

N

Mean

value

1.7907

90

5.27

4.98

Std.

Deviation

value

df

1.8904

.364

284

.716

5.59

255

.000

.010

Sig.

Heart disease

196

5.36

Lung cancer

180

3.06

2.4118

77

Breast cancer

170

2.75

1.5416

71

3.36

1.7091

2.61

239

High blood

pressure

178

4.42

1.8374

75

5.73

1.7268

5.25

251

.000

Hepatitis

175

1.81

2.2871

75

5.09

3.0632

8.32

248

.000

Tuberculosis

178

1.92

1.9223

78

3.51

2.4428

5.08

254

.000

Total

Health

Knowledge

156

20.0

9.2676

68

28.8

9.9079

6.24

222

.000

15

2.7553

�Results of t-test show that students of PU compared to students of MU were more

aware of risk factors related to lung cancer, breast cancer, high blood pressure,

hepatitis, and tuberculosis. The only non-significant difference was observed in case of

heart disease. Overall, the mean values of MU and PU students on the total health

knowledge indicates that PU students had more knowledge of risk factors for all the six

diseases listed in table as compared to MU students (Figure 1).

4-1-2) Gender Differences in Health Knowledge

Table 3) Gender Distribution of Respondents’ Health Knowledge (Percentage of correct answers)

Diseases

Lung

Breast

cancer

cancer

Average

High blood

pressure

Hepatitis

Knowledge

TB

Men

Women

Men

Women

Men

Women

Men

Women

Men

Women

Men

Women

Men

Women

Risk

Factors

Heart

disease

Smoking

84.3

86.7

93.4

95.9

57.9

44.4

54.5

57.1

26.8

23.8

32.0

40.4

58.1

58.0

Alcohol

consumption

59.4

76.7

28.2

15.6

13.0

18.7

64.1

66.0

24.5

22.4

7.5

16.1

32.8

35.9

Stress

87.4

93.1

46.9

40.3

52.9

66.4

91.7

88.3

32.9

29.4

35.0

29.7

57.8

57.9

Extra salt

43.6

54.9

43.4

36.8

42.7

35.8

76.3

88.7

31.3

25.3

36.6

28.4

45.7

45.0

Excessive

coffee

36.8

43.2

29.6

21.5

30.6

20.4

36.9

43.2

23.4

23.9

26.9

26.7

30.7

29.8

Animal fat

68.8

77.2

33.5

29.7

9.0

14.2

58.0

59.6

26.1

17.7

33.9

23.2

38.2

36.9

Polluted water

30.0

29.8

24.6

19.3

28.4

16.0

26.9

32.1

42.8

52.2

11.9

7.1

27.9

26.1

Receiving

blood

30.7

21.8

33.3

27.7

29.3

27.2

21.7

23.2

40.0

51.1

27.4

24.1

30.4

29.2

Physical

inactivity

80.7

81.0

34.5

26.8

33.1

27.1

65.4

55.5

25.3

28.7

28.8

24.7

44.6

40.7

Average

Knowledge

57.9

62.7

40.8

34.8

33.0

31.1

55.1

57.1

30.3

30.5

26.6

24.5

40.6

40.2

A number of gender differences were found in relation to; alcohol consumption

and adding extra salt to meals for heart disease (59.4% and 43.6% men as against 76.7%

and 54.9% women respectively); smoking and animal fat for breast cancer (57.9% and

9.0% men as against 44.4% and 14.2% women respectively); adding extra salt to meal

and physical inactivity for high blood pressure (76.3% and 65.4% men as against 88.7%

and 55.5% women respectively); consumption of polluted water and receiving blood for

16

�hepatitis (42.8% and

nd 40.0% men

m

as against 52.2% and 51.1% wom

women respectively);

and finally smoking and alcohol

alco

consumption for tuberculosis (32.0%

.0% and 7.5% men as

against 40.4% and 16.1%

% women respectively). Overall, women were

w

more aware of

risk factors involved in hea

eart disease and high blood pressure than

th

men, while men

were more aware of risk fa

factors involved in lung cancer, breast cancer,

ca

hepatitis, and

tuberculosis.

erences in Health Knowledge (Awareness of risk factors for diseases)

Table 4) Gender Differe

Awareness

of risk

factors for

illness

Men

Women

N

Mean

M

v

value

Deviation

Heart disease

145

5

5.05

Lung cancer

130

3

3.95

Breast cancer

126

High blood

pressure

T

T-

N

Mean

value

Deviation

1.7511

141

5.62

1.8499

2.6468

127

3.32

2.6544

3

3.08

1.6877

115

2.76

126

4

4.69

1.6794

127

Hepatitis

126

2

2.84

2.7744

Tuberculosis

128

2

2.47

Total

Health

Knowledge

116

2

22.75

Std.

Std.

Val

alue

N

Sig.

2.67

2.6

284

.008

1.90

1.9

255

.057

1.5179

1.55

1.5

239

.122

4.92

2.0938

.966

.96

251

.335

124

2.75

3.1303

.265

.26

248

.791

2.1662

128

2.34

2.2673

.479

.47

254

.632

9.5094

108

22.86

11.0178

.075

.07

222

.941

However, the apparent ge

gender differences in knowledge of disea

ease inducing factors

were statistically non-signifi

nificant (see table 4). Gendered awareness

ess of risk factors was

significant only for heartt d

disease. Thus, women students were

e more

m

aware of risk

factors involved in heart dis

isease as compared to men students.

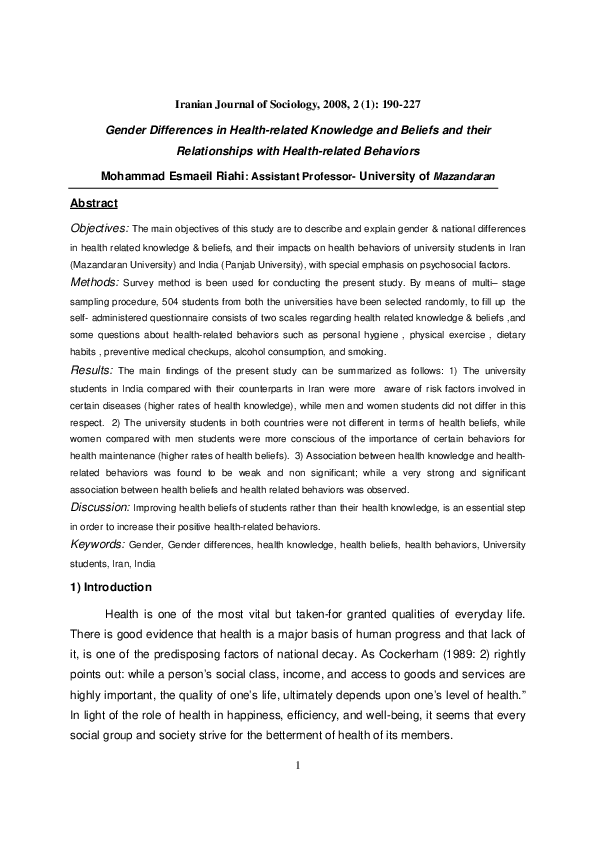

Figure 1)) Gender and National Differences

in Health Knowledge

30

Mean value

25

20

15

10

5

0

MU

PU

Men

17

Women

�Overall, it is clear that there were no significant differences between men and

women students as regards their knowledge of risk factors in the selected diseases, as

evident from t-value (.075) not significant even at 0.05 level (Figure 1).

4-1-3) Links between Health Knowledge and Health Behavior

An effort was also made to find out the linkages between health knowledge and health

related behaviors of individuals on selected diseases. The data in table 5 shows nonsignificant relationship between health knowledge and health behaviors of respondents.

Table 5) Association between Health Knowledge and Health Related Behaviors

Mean

Knowledge

about

Physical

activity

Smoking

Alcohol

Consumption

Excessive

coffee

Extra salt

Extra

Animal fat

Frequency of Health-related Behaviors

No

exercise

2.63٭

Less active

Nonsmoker

Light

smoker

3.31

Nondrinker

3.26

Light

drinker

1.95

1-3 cups

3.75

Always

2.23

Always

2.50

1.90

Moderately

active

2.70

Highly

active

Moderate

smoker

3.40

2.64

Strong

Smoker

2.75

Moderate

drinker

1.80

Heavy

drinker

2.16

1.72

Less than

Rarely

one cup

2.20

1.59

Mostly Sometimes

Rarely

2.45

2.52

2.57

Mostly Sometimes

Rarely

2.61

2.26

1.91

Never

1.69

Never

3.18

Never

2.33

F

N

Sig.

2.39

296

.068

.359

317

.783

.315

293

.814

289

.122

1.41

298

.228

1.67

294

.156

1.95

٭Mean values of health knowledge about relationship between physical activity and some diseases

For example, there were no significant differences between the knowledge of smoking

as a contributory factor in lung cancer and its influence in making a person give up

smoking. In other words, there were no significant differences between smokers and

non-smokers in terms of knowledge of harmful effects of smoking. Similarly, drinking or

non-drinking was not significantly associated with awareness of the influence of alcohol

on illness. It is interesting to note that heavy drinkers were more aware of alcohol

hazards (mean knowledge=2.16) than non-drinkers (1.95), though the F-ratio was not

significant. This suggests that drinkers are more aware of the possible harmful

consequences of alcohol than non-drinkers, and that knowledge did not function as a

deterrent. The same association holds for every item concerning adding salt to meals,

consumption of extra fat, frequency of drinking excessive coffee, and physical activity.

18

�4-1-4) Factors Associated with Health Knowledge

Table 6) Factors Associated with Health Knowledge in the Overall Sample

Associated

Factors

Mean Values of Health Knowledge in Different

Categories

F

N

Sig.

University

Mazandaran University ٭

20.2

Panjab University

28.8

39.0

223

.000

Level of

education

Undergraduate students

21.5

Postgraduate students

26.6

10.9

223

.001

Type of

residence

Far away from family

25.2

Staying with family

21.8

5.25

215

.023

Urban

Rural 19.7

5.48

222

.020

31.2

6.28

208

.000

10.2

211

.000

13.4

210

.000

Nativity

SES

Father’s

education

Mother’s

education

Low

17.3

23.7

Medium

22.4

High

Less than

middle school

Middle & high

school

Graduate &

postgraduate

12.0

21.5

25.6

Less than

middle school

14.2

Middle & high

school

Graduate &

postgraduate

26.5

22.2

٭Mean values of health knowledge rated by each category of students

As can be seen from table 6, there exists a significant association between the level of

health knowledge and the university of respondents, level of education, type of

residence, nativity, subject of study, father’s education, mother’s education, and SES of

respondent’s family.

4-2) Health Beliefs

4-2-1) University Level Differences in Health Beliefs

University-wise data reveals that

55.7 % students of MU as against 54.8%

students of PU gave high importance to health maintenance behaviors. Three health

related behaviors which have been assigned the highest importance for maintenance of

health were regular brushing of teeth (91.1%), abstaining from smoking (81.9%), and

eating fruit (79.0%). The three behaviors, which were given least importance, were

annual dental check-up (49.7%), eating fish and poultry (42.8%), and annual check up

for blood pressure (41.6%).

19

�Table 7) Distribution of Health Beliefs among the Students of

Mazandaran University and Panjab University

Level of Health Beliefs (Given importance of

behaviors for health maintenance)

List of Behaviors

Mazandaran University (%)

Panjab University (%)

Low

Medium

High

Low

Medium

High

Brush teeth regularly

0.8

13.7

85.6

----

2.9

97.1

Annual dental checkup

19.8

23.7

56.5

22.6

35.1

42.3

Regular physical exercise

9.7

17.4

73.0

9.7

25.3

64.7

7-8 hours sleep daily

3.1

20.6

76.3

4.6

13.9

81.5

Eating breakfast every day

8.9

17.4

73.6

4.7

13.1

82.2

Eating green vegetables

6.8

21.3

71.9

2.9

10.9

86.2

Eating fruit

2.3

19.5

78.2

2.5

17.6

79.9

Eating milk & dairy products

8.4

18.6

73.0

5.1

18.6

76.3

Eating fish and poultry

6.1

30.4

63.5

54.5

26.0

19.6

Annual blood pressure checkup

31.0

22.0

47.0

42.5

21.9

35.6

Not to smoke

13.0

3.2

83.8

16.3

3.9

79.8

Drink no alcohol

12.0

11.5

76.5

15.0

9.0

76.0

Avoid extra fat

16.7

28.7

54.6

19.9

14.3

65.8

Avoid excess salt

15.8

23.6

60.6

16.3

27.9

55.8

Avoid excess coffee

21.4

23.0

55.6

18.3

26.4

55.3

Avoid excess sugar

18.6

26.7

54.7

14.9

23.4

61.7

Mean

12.1

32.2

55.7

15.6

29.6

54.8

The university-wise data reveals some variations. Students of MU gave the highest

importance to regular brushing of teeth, non-smoking and eating fruit, while the students

of PU believed that regular brushing of teeth ,eating green vegetables, and having

breakfast regularly were the three most important behaviors, respectively. On the other

hand, students of MU gave the least importance to avoiding too much sugar, avoiding

extra fat and annual check up for blood pressure, whereas annual dental checkup,

annual blood pressure checkup, and eating fish and poultry were believed to be the

least important behaviors for maintenance of health by students of PU. The average

20

�ratings given by students of MU and PU about the importance of different behaviors for

health are shown in table 8, which are ranked according to their aggregate means.

Table 8) University Level Differences in Health Beliefs

Mazandaran University

(MU)

Panjab University

(PU)

Tvalue

df

Sig.

.4903

6.13

455

.000

4.24

1.4310

.538

478

.591

239

4.31

.8497

1.52

499

.127

.9629

239

4.39

.8427

4.61

500

.000

4.14

.8895

238

4.27

.9133

1.64

498

.102

251

4.20

1.2628

233

4.14

1.3901

.510

482

.610

Eating breakfast daily

258

4.03

1.0204

236

4.29

.8964

2.92

492

.004

Eating milk& dairy

products

263

4.07

.9855

236

4.21

.9763

1.59

497

.112

Regular exercise

259

4.05

1.0806

238

3.86

1.0613

1.91

495

.056

Avoid extra fat

258

3.59

1.1540

231

3.78

1.4252

1.63

487

.103

Avoid excess salt

259

3.68

1.1846

233

3.66

1.2869

.202

490

.840

Avoid excess sugar

258

3.56

1.2083

235

3.77

1.2885

1.85

491

.064

Avoid excess coffee

252

3.52

1.2732

235

3.62

1.2931

.838

485

.403

Annual dental check up

262

3.55

1.2545

239

3.29

1.1979

2.37

499

.018

Eating fish& poultry

263

3.84

.9543

235

2.37

1.2798

14.3

430

.000

Annual blood pressure

check up

255

3.19

1.3313

233

2.87

1.4453

2.51

486

.012

Total Health Beliefs

221

63.3

10.69.8

208

62.2

10.0073

1.07

427

.281

List of Behaviors

N

Mean

value

Std.

deviation

Brush teeth regularly

263

4.41

Not to smoke

247

Eating fruit

N

Mean

value

Std.

deviation

.7516

240

4.76

4.31

1.3020

233

262

4.20

.8448

Eating green

vegetables

263

4.01

7-8 hours sleep daily

262

Drink no alcohol

Significant university level differences were found for six items listed in table, of which

for three items (annual dental checkup, annual checkup for blood pressure, and eating

fish& poultry) students of MU had higher mean values than students of PU; whereas for

three other items, namely eating breakfast every day, eating fruit, and eating green

vegetables, students of PU scored higher mean values as compared to their

counterparts in MU. Also, there were no significant differences for the remaining ten

21

�items. However, there were no significant university level differences (T-value= 1.07)

when all the health beliefs were taken together, though the mean values of MU students

were higher (63.3) than that of PU students (62.2).

4-2-2) Gender Differences in Health Beliefs

The data on gender differences in health beliefs shows that on the whole 64.6% men

as against 69.3% women students gave high importance for health related behaviors

listed in table 9. This indicates a higher level of importance given by women to health

related behaviors for maintenance of health as compared to their men counterparts.

Table 9) Gender Distribution of respondents’ health beliefs

Level of Health Beliefs

Men (%)

List of behaviors

Women (%)

Low

Medium

High

Low

Medium

High

Brush teeth regularly

0.8

6.6

92.6

----

10.4

89.6

Annual dental checkup

25.2

31.4

43.4

17.4

27.0

55.6

Regular physical exercise

7.4

19.3

73.3

11.8

23.2

65.0

7-8 hours sleep daily

4.1

19.0

76.9

3.5

15.9

80.6

Eating breakfast every day

3.8

15.1

81.1

9.8

15.6

74.6

Eating green vegetables

5.3

18.1

76.5

4.6

14.7

80.7

Eating fruit

2.9

21.0

76.1

1.9

16.3

81.8

Eating milk & dairy products

4.9

20.2

74.9

8.6

17.2

74.2

Eating fish and poultry

27.5

30.8

41.7

30.2

26.0

43.8

Annual blood pressure checkup

40.6

22.6

36.8

32.5

21.3

46.2

Not to smoke

12.6

3.8

83.7

16.3

3.3

80.1

Drink no alcohol

14.2

14.6

71.3

12.7

6.1

81.1

Avoid extra fat

19.0

25.7

55.3

17.5

18.3

64.3

Avoid too much salt

18.3

32.8

49.0

13.9

18.7

67.3

Avoid excessive coffee

20.4

29.6

50.0

19.4

19.8

60.7

Avoid too much sugar

16.6

31.1

52.3

17.1

19.4

63.5

Total health beliefs

14.1

21.3

64.6

13.6

17.1

69.3

Gender wise data reveals some variations. Overall, women have paid more attention

to eating fruit and avoiding alcohol for health maintenance while men have given more

importance to non smoking and having breakfast regularly in this regard. Both men and

22

�women considered brushing teeth regularly as the most important behavior for

maintenance of health.

Table 10) Gender Differences in Health Beliefs

Men

.6530

260

Annual dental checkup

242

3.26

1.2367

259

Regular exercise

243

4.08

1.0171

254

7-8 hours sleep daily

242

4.14

.9228

258

Eating breakfast daily

238

4.27

.8561

256

Eating green vegetables

243

4.13

.9086

259

Eating fruit

243

4.18

.8640

258

Eating milk & dairy

products

243

4.17

.9332

256

Eating fish and poultry

240

3.15

1.3182

258

Annual blood pressure

checkup

239

2.85

1.3377

249

Not to smoke

239

4.33

1.2695

241

Drink no alcohol

240

4.05

1.3418

244

Avoid extra fat

237

3.57

1.2719

252

Avoid too much salt

241

3.48

1.2352

251

Avoid excessive coffee

240

3.45

1.2264

247

Avoid too much sugar

241

3.56

1.2203

252

Total health beliefs

219

61.21

9.8262

210

4.58

Standard

Deviation

Number

4.58

Mean

Value

Standard

Deviation

243

Number

Brush teeth regularly

Behaviors

Mean

Value

List of

Women

.6725

N

Sig.

.074

501

.941

TValue

3.58

1.2117

2.98

499

.003

3.85

1.1169

2.37

495

.018

4.27

.8800

1.62

498

.105

4.05

1.0560

2.60

492

.009

4.25

.9394

1.53

500

.125

4.32

.8291

1.85

499

.064

4.11

1.0284

.676

497

.499

3.15

1.3568

.025

496

.980

3.22

1.4255

2.99

486

.003

4.21

1.4539

.955

478

.340

4.29

1.2995

1.97

482

.049

3.81

1.3043

1.98

487

.048

3.85

1.2059

3.33

490

.001

3.68

1.3273

1.98

485

.048

3.85

1.2720

1.99

491

.046

64.31

10.6976

3.13

427

.002

The data in table 10 shows that on the whole, the highest mean values were for

brushing teeth regularly, followed by non smoking, and eating fruit; while the lowest

mean values were for annual dental check up, followed by eating fish and poultry, and

annual blood pressure checkup. However, significant gender differences were found for

nine items listed in the table, of which for seven items (annual dental checkup, annual

23

�blood pressure checkup,, n

non-drinking alcohol, avoidance of anim

imal fat; excess salt;

coffee, and sugar) women

en had higher mean values than men.. In two items that is,

regular exercise and havin

ving breakfast men students scored high

gher mean values as

compared to women stude

dents. There were no significant gender

er differences for the

remaining seven. It implies

es that in general, women students gave

e more importance to

health maintenance behavio

viors than men. It can be inferred from the

he above analysis that

by and large men and wome

men students differ on their ‘health beliefs’

fs’ (Figure 2).

Figure 2)

2 Gender and National Differences

in Health Beliefs

70

Mean value

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

MU

PU

Men

Women

4-2-3) Links between Heal

ealth Beliefs and Health Behaviors

In the present study, the q

question of whether variations in the prevalence

pr

of healthrelated behaviors were ass

ssociated with the level of beliefs aboutt iimportance of those

behaviors for health main

intenance was analysed. Similar to prev

revious studies, clear

associations were observed

ed for almost all items included in this study

udy.

As can be seen from the table,

ta

for all items (except avoidance of excessive coffee) a

significant association could

uld be seen between the frequency or inte

tensity of carrying out

the behavior and the mean

an values of the associated belief. For example,

ex

people who

brush their teeth twice or more

m

times daily believe (mean value was

as 4.74) this behavior

to be more important than

n those who brush their teeth once a day

ay (4.56), who in turn

believe it to be more impo

portant than those who brush their teeth

h less frequently than

once per day (3.88). F-ratio

tio for this association comes out to be sig

significant at .01 level

of confidence (F = 13.0,, N = 500, P <. 01). It implies that there

th

exist significant

24

�differences in belief rankings according to frequency of brushing teeth, indicating strong

influence of health beliefs on healthy behavior on this item.

Table 11) Association between Health Beliefs and Health-related Behaviors

Mean Health

Beliefs about

Frequency of Health-related Behaviors

2 times or

more a

day

4.74٭

Always

Once a

day

Once a

week

Rarely or

never

4.56

Once per

every 2-3

days

3.88

4.00

4.12

Mostly

Sometimes

Rarely

Never

4.53

4.24

3.82

3.27

3.65

Once a

day or

more

4.52

Once a

day or

more

4.43

Once a

day or

more

4.37

Regularly

Every 2-3

days

About once

a week

Rarely or

never

3.99

Every 2-3

days

3.90

About once

a week

4.05

Every 2-3

days

4.07

About once

a week

4.16

Mostly

4.08

Sometimes

About

once a

month

3.57

About

once a

month

3.71

About

once a

month

3.84

Rarely

3.37

3.92

3.68

3.38

2.62

Always

3.81

Mostly

3.50

Sometimes

3.66

Rarely

3.88

Never

3.31

Always

Mostly

Sometimes

Rarely

Never

3.35

Always

3.13

Mostly

3.56

Sometimes

3.85

Rarely

3.84

Never

Avoid too much

sugar

3.21

3.47

3.31

3.87

4.01

More than

3 cups

2.33

1-3

Cups

3.30

Less than

one cup

3.37

Rarely

Never

Avoid excessive

coffee

3.57

3.60

Brush teeth

regularly

Eating breakfast

daily

Eating green

vegetables

Eating fruit

Eating milk & dairy

products

Annual blood

pressure checkup

Avoid extra fat

Avoid too much salt

Drink no alcohol

Not to smoke

4.40

Rarely or

never

N

Sig.

13.0

500

.000

2.91

483

.000

15.2

4.28

Heavy

drinker

3.08

Heavy

smoker

4.16

Moderately

active

4.25

Moderate

drinker

3.14

Moderate

smoker

3.16

Less

active

3.89

Light drinker

497

.000

6.98

497

.000

10.3

494

.000

14.1

465

.000

2.47

470

.043

3.55

Never

4.59

Highly active

Physical exercise

3.60

Rarely or

never

F

3.27

Light smoker

No

exercise

3.63

Nondrinker

4.33

Non-smoker

3.68

4.31

7.39

.988

482

483

472

.001

.000

.414

13.2

496

.000

14.4

465

.000

3.03

468

.029

٭Mean values of health beliefs about the importance of brushing teeth regularly for health.

The same association holds for every item concerning having breakfast, regular

exercise, eating green vegetables, fruit, milk & dairy products, annual blood pressure

check up, non smoking, non drinking, avoiding extra fat, salt, and sugar. On the whole,

25

�there was a significant association between total health beliefs and health-related

behaviors that is behaviors that were believed to be more important for health

maintenance, carried out by more individuals than behaviors which were believed to be

less important. In other words, those who scored higher on health belief values

positively practiced better health behaviors.

The findings of present study are in line

with those studies conducted by Wardle and Steptoe, 1991; Calnan and Rutter (1988);

Steptoe and Wardle (1992); Courtenay (2002); Cody and Lee (1982); Osaka et al.

(1999); Steptoe et al. (2002); Kurtz et al. (1992); Callaghan (1995); Gorin (1992);

Harnack et al. (1997); and Monneuse et al. (1997).

4-2-4) Factors Associated with Health Beliefs

As can be seen from table, there is significant association between level of health

beliefs with gender, nativity, health behaviors of family, health locus of control, and

health concern. The data shows that health beliefs were higher among women students

and students who were residents of urban areas. Also it was higher for those whose

families observed higher level of positive lifestyle, students who enjoyed a good sense

of control, and those who were more concerned about their health status.

Table 12) Factors Associated with Health Beliefs in the Overall Sample

Associated

Factors

Mean values of health beliefs in different categories

Gender

Men

Nativity

Health locus

of control

Health

concern

Health

behaviors of

family

61.2٭

Urban 63.5

Slightly internal

57.0

Low

59.3

N

Sig.

Women

64.3

9.81

428

.002

Rural

60.4

6.85

422

.009

3.10

399

.046

3.21

422

.023

4.60

371

.001

Moderately internal

62.4

Medium

60.7

F

Strongly internal

63.6

High

63.6

Very high

64.3

Very low

Low

Medium

High

Very high

58.5

61.0

63.4

66.3

65.1

٭Mean values of health beliefs rated by each category of students

5) Discussion

On the basis of the above analysis, it was found that differences in health

knowledge of PU and MU students were quite significant; while the differences in health

beliefs were non significant. In other words, awareness of students of PU and MU about

26

�the various health related risk factors was different. It was generally observed that

students of PU were more aware of risk factors involved in certain diseases than the

students of MU. However, in terms of health beliefs, students of MU and PU gave

almost the same importance to health maintenance behaviors. However, significant

differences existed in some items, namely students of PU compared with students of

MU gave more importance to regular brushing of teeth, eating breakfast daily, and

eating green vegetables; while students of MU gave more importance to annual dental

check up, eating fish and poultry, and annual blood pressure check up.

Further, in line with previous studies no significant gender differences in health

knowledge could be observed. In other words, awareness of men and women students

about some risk factors for illness was similar, except about heart disease about which

women students showed more awareness of risk factors for heart disease than men

students. In relation to health beliefs, men students differed significantly from women

who gave more importance to behaviors such as annual dental checkups, annual blood

pressure measurement, avoiding alcohol; animal fat; excess salt; coffee; and sugar as

health enhancing measures. On the other hand, men students believed regular exercise

and eating breakfast daily as more important for their health maintenance. Also, in line

with previous studies association between health knowledge and health related

behaviors was found to be weak and non significant; while a very strong and significant

association between health beliefs and health related behaviors was observed. It

implies that health knowledge does not lead necessarily to risk reducing or healthenhancing behaviors, while health beliefs, to a large extent, improve the health related

behaviors. Finally, it was found that there exist significant associations between health

knowledge and some factors such as, being a student of PU, being postgraduate

students, living in urban areas, living far away from family, having more educated father

and mother, and belonging to higher SES families. Further, some other factors such as

being a woman, living in urban areas, belonging to more healthy families, enjoying a

good sense of control, and being more concerned about personal health were

associated with higher level of health beliefs.

The results in the present study are in line with those reported by Wardle and

Steptoe (1991); Kurtz et al., (1992), Kapoor et al., (1995); and Avis et al., (1996). All

these studies confirmed that both smokers and nonsmokers were well informed about

27

�the adverse effects of smoking indicating that mere provision of information on hazards

of smoking may not be enough to reduce the prevalence of smoking. These findings are

also supported by other studies such as those of Kurtz et al., (1992); Naslund and

Fredrikson (1993); Frost (1992); Avis et al., (1990); and Jerkegren et al., (1999). All

these studies indicate a weak and non-significant relationship between health

knowledge and health behaviors, suggesting that health knowledge does not

necessarily lead to risk reducing behaviors.

These findings are consistent with previous studies about gender differences on

health beliefs. For example, Steptoe and Wardle (1992) found that gender differences in

belief ratings were uniform across eight European countries, for instance, in all these

countries; women rated fat avoidance and moderation in alcohol consumption as more

important than men. Similarly Courtney et al. (2002) who conducted a study on

gender/ethnic differences on health beliefs and behaviors found that men students had

significantly riskier beliefs in diet, substance use, medical compliance, and preventive

care than women students. Also, Cody and Lee (1989) found that women scored

significantly higher than men on skin protection knowledge, intension, and behavior.

In the light of the results of this study and also those of other studies, association

between health knowledge and health related behavior is inconsistent and non

significant, while health beliefs have significant and consistent association with health

behaviors of students. This finding strongly suggests that, although knowledge remains

an important factor that must be addressed in health education programmes, in order to

motivate young college students to take appropriate prevention measures when

exposed to unhealthy behaviors, educational efforts must focus primarily on the

formation of attitudes and beliefs towards health related behaviors. Prevention

approaches based on social learning theory have emphasized developing social and

personal skills in youth and young adults to enable them to resist pro-drug and

unhealthy environmental and peer pressures. Therefore, educational efforts directed

toward young college/university students should include strategies that help reduce the

influence of the peer group. Further, all health interventions by the authorities have to

adopt multi-pronged strategies to improve health knowledge, health beliefs, health

concern, and health related behaviors.

28

�However, further studies are needed for monitoring progress in enhancing health

knowledge & beliefs, reducing critical health risk behaviors, or improvement in positive

health habits among young students. The periodic research studies in this area and at

the cross-national levels would be necessary to establish priority areas for future

interventions and to monitor their effects. Further, a national study among the university

students of each country on a larger scale, with the cooperation of all institutions for

higher education could make a significant contribution to the literature and the future

health of college/university students in Iran and India. Further studies, of course, can be

conducted on other socio-economic groups of society to compare the results with the

university students and finding out the place of students in health hierarchy. Finally, in

order to clarify which factors best explain cross-national differentials observed in health

related behaviors, future research needs to go beyond the set of determinants available

for the current study and strike into the more subtle aspects of health related behaviors

across settings.

☼References:

- Abroms L., et al., (2003). Gender differences in young adults’ beliefs about sunscreen use. Health

Education & Behavior, Vol. 30(1): 29-43.

- Avis NE, McKinlay JB., & Smith KW. (1990). Is cardiovascular risk factor knowledge sufficient to influence

behavior?. Am.J Prev Med, 6, 137-44.

- Awasthi P., et al., (2006). Health beliefs and behavior of cervix cancer patients. Psychology and

Developing Societies, 18, 1.

- Bassey EB. et. Al., (2007). Knowledge of and attitudes to AIDS among traditional birth attendants in rural

communities in Cross River State, Nigeria. Int Nurs Rev, 54(4): 354-8.