Harpsichord &

fortepiano

Autumn 2010

VALLOTTI AS THE IDEAL GERMAN

GOOD TEMPERAMENT

———————————————————————————————————————————

By Claudio Di Veroli

1. TEMPERAMENT IN A NUTSHELL

This article assumes familiarity with basic concepts of temperament, easily available nowadays

(e.g. from Lindley, 1980 or Di Veroli, 2009), but anyway let us briefly review the main concepts.

Intervals are mostly nowadays measured in Cents, where 100 Cents is an Equal-Temperament

semitone: thus the octave has 1200 Cents. In 12-note music, instruments (e.g. keyboards) are

usually tuned starting from any note, then following the Circle of Fifths up and down:

Eb - Bb - F - C - G - D - A - E - B - F# - C# - G#

One tunes the above 11 fifths (pure or tempered) and the last fifth (G#/Ab-Eb) is left to “close

the circle”. In Medieval Pythagorean Intonation one tunes the 11 fifths pure: the result is a

very mistuned G#-Eb, “narrow” by 23.46 Cents, the “Pythagorean comma”. That is a problem,

but the real issue of temperament lies elsewhere. Every 4 fifths “produce” a major third (e.g. CG-D-A-E), but if we tune the fifths pure, the major third is too “wide” by 21.51 Cents, the

“Syntonic comma”. This is much wider than modern Equal Temperament (ET) major thirds,

barely acceptable with their deviation of 13.60 Cents. The 21.51-Cents-wide “Pythagorean major

thirds” are perceived as truly dissonant. When Renaissance and Baroque musicians needed

consonant major thirds, they adopted Meantone Temperament. In its usual variant, every one

of the 11 fifths is tuned “narrow” by 1/4 Syntonic Comma, yielding 8 perfectly pure major thirds:

Eb-G, Bb-D, F-A, C-E, G-B, D-F#, A-C# and E-G#. The sound quality is ravishing, but here also—

and inevitably—the tuning leaves a “wolf fifth” at G#-Eb: much more significantly, the remaining

4 thirds are unplayable “wolves”, each wide by 41 Cents.

2. GOOD TEMPERAMENTS AND VALLOTTI

In High Baroque times in Germany c.1690-1750 meantone quickly lost ground (Rasch 1984) to

Good temperaments (Werckmeister’s “Gute Temperatur”) whereby fifths were tuned with

different “sizes” in diverse ways. The diatonic fifths (F_C_G_D_A_E_B) were still tuned quite

narrow, but the other were pure or slightly wide. This arrangement of fifths yielded a Circle of

Major Thirds whereby the most usual ones were very good (much better than ET) while others

were much worse yet still playable. The main advantage of Good temperaments over Meantone

was that, with different degrees of consonance, they were “circular”, i.e. all the fifths and all the

major thirds were now playable, as required by the music of the time. A well-known German

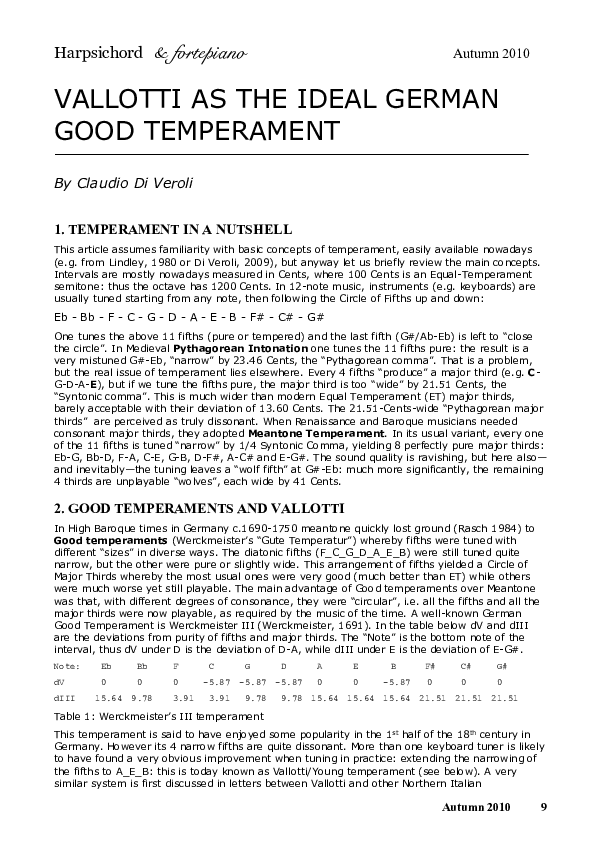

Good Temperament is Werckmeister III (Werckmeister, 1691). In the table below dV and dIII

are the deviations from purity of fifths and major thirds. The “Note” is the bottom note of the

interval, thus dV under D is the deviation of D-A, while dIII under E is the deviation of E-G#.

Note:

Eb

Bb

F

dV

0

0

0

dIII

15.64

9.78

3.91

C

-5.87

3.91

G

D

-5.87 -5.87

9.78

A

E

0

0

B

-5.87

9.78 15.64 15.64 15.64

F#

C#

G#

0

0

0

21.51 21.51 21.51

Table 1: Werckmeister’s III temperament

This temperament is said to have enjoyed some popularity in the 1st half of the 18th century in

Germany. However its 4 narrow fifths are quite dissonant. More than one keyboard tuner is likely

to have found a very obvious improvement when tuning in practice: extending the narrowing of

the fifths to A_E_B: this is today known as Vallotti/Young temperament (see below). A very

similar system is first discussed in letters between Vallotti and other Northern Italian

Autumn 2010

9

�theoreticians from the 1730’s on, becoming widely known in Italy after Vallotti’s tuning criteria

were enthusiastically endorsed in a treatise that reached wide diffusion (Tartini, 1754). Vallotti’s

temperament avoids the very narrow fifths of Werckmeister’s III, yielding a similar Circle of

Major Thirds. For more details see Lindley (1980). Find a full analysis of Good temperaments and

particularly Werckmeister’s and Vallotti’s ones in Di Veroli (2009, Chapters 9 and 11).

Note:

Eb

Bb

dV

0

0

dIII

13.69

9.78

F

C

-3.91

-3.91

5.87

5.87

G

D

A

E

-3.91 -3.91 -3.91 -3.91

5.87

B

F#

C#

G#

0

0

0

0

9.78 13.69 17.60 21.51

21.51 21.51 17.60

Table 2: Vallotti’s temperament (Pythagorean comma version)

Fig. 1. Pages from Tartini’s Trattato di Musica, Padua 1754.

Vallotti’s tuning slightly “favours” tonalities with flats. Versions of Vallotti shifted one fifth

clockwise—slightly favouring the sharps instead—are also likely to have been in use in ancient

times: they are an obvious modification of Werckmeister III, tempering his pure A_E_B. The

earliest descriptions of shifted-Vallotti all date from the 2nd half of the 18th century (Barbieri,

Vicenza 1986, p.44). In modern times the first source found for it was Young’s Nº 2

temperament (Young, 1800), hence shifted-Vallotti is usually called Vallotti/Young.

Note:

Eb

Bb

F

dV

0

0

0

dIII

17.60

13.69

9.78

C

-3.91

5.87

G

D

A

E

B

-3.91 -3.91 -3.91 -3.91 -3.91

5.87

5.87

9.78 13.69 17.60

F#

C#

G#

0

0

0

21.51 21.51 21.51

Table 3: Vallotti/Young temperament

Truly circular and enharmonic, these tunings are ideally suitable for High Baroque music that

needs full circularity-cum-diversity (see Di Veroli, 2009 section 9.8). This includes the works of

J.S. Bach, for which Vallotti provides precisely the amount of diversity required by his frequency

of use of major thirds (ibidem sect. 21.10). Vallotti can be tuned easily and accurately in

keyboards utilising either ancient or modern methods (ibidem sect. 13.16). It is also easy to fret

in lutes and viols, quite natural in instruments of the violin family (ibidem sect. 15.11 and 16.5)

and it can be followed with no issues on Baroque wind instruments.

3. VALLOTTI’S MODERN POPULARITY AND CRITICISM

Vallotti is a very popular unequal temperament nowadays. A few dates in its modern history:

1951: Dr. Barbour in his widely-read treatise (Barbour, 1951, pp.182-183) formulated ‘the ideal

form of Werckmeister’s “correct” temperaments and of Neidhardt’s “circulating” temperaments

and of all “good” temperaments that practical tuners have devised by rule of thumb’ as a

“Temperament by Regularly Varied Fifths”. Though he only knew Young’s variant, Barbour’s

system was actually an exact mathematical average between Vallotti and Young which, as

Barbour acknowledged in p.184, “cannot be surpassed from the practical point of view”.

1977: Dr. Lindley in his paper in Early Music (Lindley, 1977) stated that “German ‘Good

temperaments’ … Dozens of 18th-century musicians praised this kind of tuning. … One such

tuning, praised by Tartini … was used at Padua by Francescantonio Vallotti, organist and resident

composer from the 1720s ...”. This was the only Good temperament described by Lindley in this

very-influential paper.

Autumn 2010

10

�1980-1: Publication of the author’s Unequal Temperaments book, which may also have helped

to Vallotti’s diffusion. Writings on “Bach’s Temperament” in Early Music (Barnes, 1979 and Di

Veroli, 1981) justify the “optimality” of both Barnes’s temperament and Vallotti for the music of

J.S. Bach. (Note: no document has ever been found relating Bach to any temperament).

From the 1980’s on quite a few leading Baroque period instruments adopted Vallotti, which is in

widespread use today. However, the modern world seems to need the continuous revision of our

knowledge, writers often embarking in “crusades” and “counter-reformations”. Inevitably most

modern-day deductions about past musical customs are correct: therefore their revisions

sometimes can be misleading. In recent years the modern use of Vallotti has been criticised on

two types of grounds: musical and historical.

In musical terms, some are against the use of Good temperaments in Baroque music making.

Some influential musicians in mid-18th century like Gottfried Silbermann and Telemann (1742)

advocated 1/6 Syntonic comma meantone instead, supported in modern times by Prof. Duffin.

Those proposals were misguided. The deviations of the 12 Major Thirds show clearly how Vallotti

is a circular temperament, while 1/6 Syntonic comma is not: not only it sports a wolf fifth, but

also four major thirds intolerably wide (full details in Di Veroli, 2009 section 5.8).

Note:

Eb

Bb

F

C

G

D

A

E

B

F#

C#

G#

1/6 S.c. 7.17

7.17

7.17

7.17

7.17

7.17

7.17

7.17

26.72

26.72 26.72 26.72

Vallot. 13.69

9.78

5.87

5.87

5.87

9.78 13.69 17.60 21.51

21.51 21.51 17.60

Table 4: Major Thirds: 1/6 Syntonic-Comma Meantone vs Vallotti’s temperament

On the historical side it has been argued that Vallotti, however useful for Baroque music, is a

proposal too much restricted in time (around mid/late 18th century) and space (North-Eastern

Italy). To disprove these objections is the main goal of this article.

4. BAROQUE HISTORICITY OF VALLOTTI

Vallotti’s temperament in its early version by Riccati was actually formulated years earlier than

Tartini’s endorsement: at least one Italian church organ was tuned to it before the Trattato saw

the light in 1754. Unfortunately, there are no documents showing how/where widespread its use

was at the time. Therefore, there would seem to be “prima facie” no historical justification for its

use in German High Baroque music. We have already seen a first justification for Vallotti if we

consider it as a minor modification—though with important consequences—of tuning following

Werckmeister III (1691): this is something most practical Baroque tuners could easily achieve.

Unfortunately again this fact, however likely, was not documented in ancient times and cannot

be proved.

Another way to look at the issue is to try and verify Barbour’s assertions—which he stated

without any supporting statistics—about Young (thus also Vallotti) as the ‘ideal form … of “good”

temperaments’. Let us start from the circular temperaments proposed by the main German HighBaroque writers on the matter, Werckmeister and Neidhardt, and see how much their opera

omnia compares with Vallotti. One way to do that, both intuitive and acoustically correct, is to

find out the shape of the Circle of Major Thirds for “the average circular Werckmeister’s

temperament” and “the average circular Neidhardt’s temperament”.

5. AVERAGING TEMPERAMENTS

Nowadays, when accurate numerical data for the main historical temperaments are available

neatly arranged in computer spreadsheets (http://temper.braybaroque.ie/spread.htm), it is not

difficult at all to compute an average of a set of several temperaments: one simply computes the

arithmetical average of the deviations in Cents for each one the 12 Fifths. It can be

mathematically proved that the result is an acoustically-correct 12-note temperament.

PROOF. The only requirement for a succession of 12 deviations of Fifths in Cents Di (i=1…12) to

be a musical temperament, is that their sum ∑i=1,12 Di has to add up to the Pythagorean Comma

(Pc = 23.46 Cents) with negative sign. Let now be n different temperaments defined as n

successions of 12 deviations each, k=1…n, each one fulfilling the above requirement. We thus

have ∑i=1,12 Dki = -Pc , for each k=1…n.

Their averages are a succession of 12 Fifth deviations obtained as

Autumn 2010

11

�Ai = (∑k=1,n Dki )/n , for each i=1,12. Let us now add them up:

∑i=1,12 Ai = ∑i=1,12 [(∑k=1,n Dki)/n]

= [∑i=1,12 (∑k=1,n Dki)]/n

= [∑k=1,n (∑i=1,12 Dki)]/n

= [∑k=1,n (∑i=1,12 Dki)/n]

= [∑k=1,n (-Pc)/n]

= n x (-Pc)/n = -Pc

We have thus proved that the average deviations Ai are a musical temperament.

6. WERCKMEISTER’S CIRCULAR TEMPERAMENTS AVERAGE

Let us now average Werckmeister’s five circular temperaments:

“Werckmeister III”, his 1st circular temperament, also named “Werckmeister 1st”

“Werckmeister IV”, his 2nd circular temperament, also named “Werckmeister 2nd”

“Werckmeister V”, his 3rd circular temperament, also named “Werckmeister 3rd”

“Werckmeister VI”, his last system of 1691, which he also called “Septenarius”

“Werckmeister Continuo” temperament from his continuo treatise of 1698.

The result of the spreadsheet calculations is shown in the chart below: the Circle of Major Thirds

is clearly, to all practical purposes, very near to Vallotti/Young temperament: not even an

experienced tuner can tell the difference by ear.

Fig. 2. Average of Werckmeister’s Circular temperaments vs Vallotti/Young.

7. NEIDHARDT’S CIRCULAR TEMPERAMENTS AVERAGE

Let us now average Neidhardt’s circular temperaments, collected in his magnum opus (Neidhardt

1732) and revived by a few modern tuners. Here the matter is more complicated because there

are now 21 temperaments and many of them are not circular temperaments. The following 10

ones are clearly to be excluded from the average:

Neidhardt Pythagorean - Pythagorean tuning

Neidhardt 5th Circle #1 - Equal Temperament

Neidhardt 5th Circle #2 - Major Thirds all equally-tempered

Neidhardt 5th Circle #3 - Major Thirds all equally-tempered

Neidhardt 5th Circle #4 - Major Thirds all equally-tempered

Neidhardt

5th

Circle

#5

Major

Thirds

randomly

10 and 16 C.: coarse approximation to Equal Temperament

tempered

between

Neidhardt 5th Circle #6 - Major Thirds all equally-tempered

Neidhardt 5th Circle #9 - Major Thirds all equally-tempered

Neidhardt 5th Circle #12 - (same properties as 5th Circle #5)

Neidhardt Chapter VII Example #1 - This is a Just Intonation variant

Autumn 2010

12

�We will thus average Neidhardt’s remaining 11 temperaments only, all of them circular:

Neidhardt 5th Circle #7

Neidhardt 5th Circle #8, suitable for a Big City

Neidhardt 5th Circle #10

Neidhardt 5th Circle #11

Neidhardt Chapter VII Example #2

Neidhardt Chapter VII Example #3

Neidhardt 3rd Circle #1, suitable for a Village

Neidhardt 3rd Circle #2, suitable for a Small Town

Neidhardt 3rd Circle #3

Neidhardt 3rd Circle #4

Neidhardt 3rd Circle #5

The Figure below shows the resulting Circle of Major Thirds: clearly the average is quite near to

Vallotti’s temperament. Both curves in the chart can be heard and described as “mid-unequal” by

comparison against other circular systems, some much more unequal, some much less unequal,

utilised in other ancient times and pleces.

Fig. 3. Average of Neidhardt’s Circular temperaments vs Vallotti.

Certainly the curves in the chart show Neidhardt’s temperaments to be on average slightly less

unequal than Vallotti, but this does not detract from the argument for the latter. There is scarce

evidence for the practice of Neidhardt’s circular temperaments in Baroque times and, after all, he

was a supporter of Equal Temperament. Some modern writers have described how Baroque

German musicians would “evolve” from an openly unequal Vallotti into Equal Temperament “via”

intermediate mildly-unequal systems à la Neidhardt (like his “3rd Circle No.2 for a Small Town” or

the even less unequal “3rd Circle No.5”). However, the historical record seems to show otherwise.

The change was quite swift indeed: by the mid-18th century old musicians like J.S.Bach and

Telemann would still be following very unequal tunings, while young C.P.E. Bach and others were

already tuning in Equal Temperament, which was quickly gaining ground and would soon become

predominant.

8. CONCLUSION

Vallotti and Vallotti/Young temperaments are ideal historical and practical tuning systems for

High Baroque music making. Most importantly, regardless of their initial time and area coverage,

they also match very closely the “average” of the circular temperaments described by the main

German High Baroque writers on temperament: Werckmeister and Neidhardt.

Autumn 2010

13

�Works Cited

Barbieri, Patrizio. “L’espressione degli ‘Affetti’ mediante l’ineguale accordatora degli strumenti a

tasto nel settecento veneto”, Organaria veneta: patrimonio e salvaguardia. (Vicenza 1986.)

Barnes, John. “Bach’s keyboard temperament”, Early Music 7 (1979): 236-249.

Barbour, J. Murray. Tuning and Temperament: A Historical Survey. (East Lansing:

Michigan State College Press 1951.; repr. New York: Da Capo Press, 1972).

Di Veroli, Claudio. Unequal Temperaments and their role in the performance of early music.

(Farro, Buenos Aires 1978.)

__________. “Bach's temperament”, Early Music 9 (1981): 219-221.

__________. “Tuning the tempérament ordinaire”, Harpsichord & fortepiano 10/1 (Autumn 2002).

__________. Unequal Temperaments: Theory, History and Practice (Scales, Tuning and Intonation in

Musical Performance). 2nd revised edition, eBook. (Bray, Ireland: Bray Baroque 2009).

Duffin, Ross W. Why I hate Vallotti (or is it Young?). [Online 2009],

<http://music.cwru.edu/duffin/Vallotti/default.html>

Lehman, Bradley. Johann Georg Neidhardt’s 21 temperaments of 1732. [Online 2006].

<http://harpsichords.pbwiki.com/f/Neidhardt_1732_Charts.pdf> Ssee also Neidhardt 1732.

Lindley, Mark. “Instructions for the clavier diversely tempered”, Early Music 5 (1977): 18-23.

__________. “Temperaments”, The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians.

(London, Washington and Hong Kong: Macmillan, 1980).

__________. “Temperament”, The Harpsichord and Clavichord: An Encyclopedia. Ed.

Igor Kipnis. (New York: Routledge, 2007). [This does not reflect the article’s date:

most entries in this compilations were sent to Prof. Kipnis in the 1980’s].

Neidhardt, Johann Georg. Gäntzlich erschöpfte, mathematische Abtheilungen des diatonischchromatischen, temperirten Canonis Monochordi. Ch.VI and VII. (Eckhardt, Königsberg

and Leipzig, 1732. [Full tables are available online: see Lehman 2006]

Rasch, Rudolf A. “Friedrich Suppig and his Labyrinthus musicus of 1722”, The Organ Yearbook 15 (1984):

33-53.

Tartini, Giuseppe. Trattato di Musica secondo la vera scienza dell'Armonia. Manfrè, Padova

1754. Facsimile reprint (Kessinger Publishing: LaVergne, Tennessee, 2009).

Telemann, Georg Philipp. “Neuen Musikalischen Systems”, c.1742 rev. 1767. Modern reprint in Ch.80 of

Singen ist das Fundament zur Music in allen Dingen. Eine Dokumentensammlung.

(Leipzig: Philipp Reclam, 1985).

Werckmeister, Andreas. Musicalische Temperatur. (Quedlinburg, 1691).

__________. Die Nothwendigsten Anmerckungen und Regeln, wie der Bassus continuus

oder General-Bass wol könne tractiret werden. (Struntz, Aschersleben 1698).

Young, Thomas. "Outlines of Experiments and Inquiries respecting Sound and Light".

Philosophical transactions of the Royal society of London 90/1 (1800): 143.

__________________________________________________________________

…

About our Contributors

Claudio Di Veroli is a harpsichord player and tuner from Buenos Aires. Having spent

some years in London, Rome and Paris, since 2001 he lives in Bray, Ireland. He has

published books and articles on keyboard tuning and performance, some of them in

Harpsichord and Fortepiano.

Autumn 2010

14

�

Claudio Di Veroli

Claudio Di Veroli