Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser.

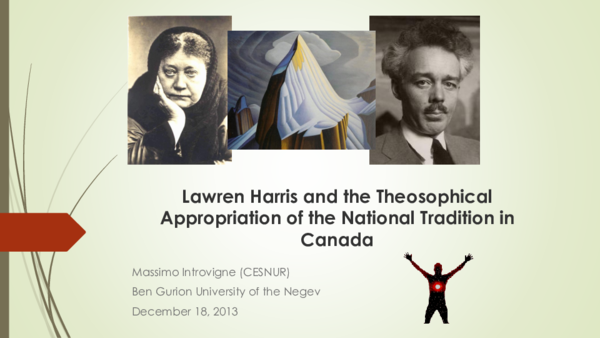

Lawren Harris and the Theosophical Appropriation of the National Tradition in Canada

Lawren Harris and the Theosophical Appropriation of the National Tradition in Canada

Lawren Harris and the Theosophical Appropriation of the National Tradition in Canada

Lawren Harris and the Theosophical Appropriation of the National Tradition in Canada

Lawren Harris and the Theosophical Appropriation of the National Tradition in Canada

Related Papers

Was the Lithuanian painter Čiurlionis a Theosophist? Čiurlionis' contacts with Theosophy, between myth and reality

Theosophical Appropriations: Esotericism, Kabbalah, and the Transformation of Traditions, edited by Julie Chajes and Boaz Huss

Theosophical Appropriations: Esotericism, Kabbalah, and the Transformation of Traditions, edited by Julie Chajes and Boaz Huss2016 •

Theosophical Appropriations Esotericism, Kabbalah and the Transformation of Traditions Editors: Julie Chajes, Boaz Huss The thirteen chapters of this volume examine intersections between theosophical thought and areas as diverse as the arts, literature, scholarship, politics, and, especially, modern interpretations of Judaism and kabbalah. Each chapter offers a case study in theosophical appropriations of a different type and in different context. The chapters join together to reveal congruencies between theosophical ideas and a wide range of contemporaneous intellectual, cultural, religious, and political currents. They demonstrate the far-reaching influence of the theosophical movement worldwide from the late-nineteenth century to the present day. Contributors: Karl baier, Julie Chajes, John Patrick Deveney, Victoria Ferentinou, Olav Hammer, Boaz Huss, Massimo Introvigne, Andreas Kilcher, Eugene Kuzmin, Shimon Lev, Isaac Luberlsky, Tomer Persico, Helmut Zander.

Enchanted Modernities: Theosophy and the arts in the modern world. University of Amsterdam, 25-27 September 2013. Harald Szeemann (1933-2005) was one of the most prominent curators of his generation, having organized more than 150 art shows during a career that spanned almost 50 years. Far from being concerned only with contemporary art, he organically worked on a body of exhibitions characterized by a vivid interest for topics such as utopia, Gesamtkunstwerk, the history of intentions and obsessions, trying to build an European history of alternatives based on a multi-disciplinary approach and on the study of Art brut, psychoanalysis, pataphysics, religious devotion and, last but not least, Theosophy and Anthroposophy. In this context, a special role is played by his lifelong project of building a museum on Monte Verità, the hill in Ticino which hosted from the second part of the XIX century onwards different groups and colonies of anarchists, vegetarians, nudists, artists and life reformers. In my paper, I will address the role of Theosophy and Anthroposophy in Szeemann’s practice as a curator, as well as in his thinking about modern art, particularly focusing on the exhibitions in which he presented works by Rudolf Steiner, or had Theosophy as a central theme: the already mentioned Monte Verità (1978), Der Hang zum Gesamtkunstwerk (1983) andMoney&Value–The last taboo (2002), that represent mayor examples of mainstream temporary display of Theosophy-related material in the last decades. Special attention will be devoted also to the relationship and professional collaboration with Joseph Beuys, presented in 17 of Szeemann’s mayor exhibitions and considered by the curator to be the most important artist of the second half of the XX century, and to an unrealized project dated 1975, La Mamma, meant to focus on the idea of a feminine deity and to the body of women, which was supposed to present also the life and work of Helena Blavatsky and Annie Besant.

The article details the influence of Christian Science on the visual arts, from early artists to celebrated contemporary artist Joseph Cornell

The relationships of Italian Futurist painter Giacomo Balla with Theosophy and esotericism. A paper presented at the conference "Visions of Enchantment: Occultism, Spiritualism, and Visual Culture", University of Cambridge, 17-18 March 2014

Reginald Willoughby Machell (1854–1927) was a promising young artist from a prominent family in North-West England when he was introduced to Madame Blavatsky in 1886. Machell joined the Theosophical Society, abandoned his academic style and decided to devote his life to creating didactical art aimed at illustrating Blavatsky's doctrines. When the Theosophical Society split after Blavatsky’s death, Machell sided with the American faction led by William Q. Judge and later by Katherine Tingley. In 1900, the artist moved to Lomaland, Tingley’s Theosophical colony in California, where he remained for the next 27 years of his life. He continued to paint Theosophical subjects and to write articles on the relationship between Theosophy and the arts. He also emerged as a successful wood carver and as a gifted teacher of younger Theosophical painters, who formed the so called Lomaland Art Colony. Best remembered for a single iconic Theosophical painting, The Path, Machell was extremely popular for several decades among alla branches of the Theosophical movement. At the same time, his almost exclusive focus on Theosophy led to his marginalization in wider artistic circles, although other teachers recruited by Tingley for the Lomaland art school, including Maurice Braun (1877–1941), eventually managed to be accepted by the American art establishment.

RELATED PAPERS

Journal of Art Historiography 19

‘Rudolf Steiner’s engagement with contemporary artists’ groups: art-theoretical discourse in the anthroposophical milieu in Germany in the early 20th century’2018 •

Julie Chajes, Boaz Huss (eds.): Theosophical Appropriations: Esotericism, Kabbalah, and the Transformation of Traditions

Theosophical Orientalism and the Structures of Intercultural Transfer: Annotations on the Appropriation of the Cakras in Early TheosophyThe Idea of North: Myth-Making and Identities

Feminine Androgyny and Diagrammatic Abstraction: Science, Myth and Gender in Hilma af Klint’s Paintings2019 •

The Occult in Modernist Art, Literature, and Cinema. Eds. Tessel M. Baduin & Henrik Johnsson. [Palgrave Studies in New Religions and Alternative Spiritualities]. Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 49-66.

Visionary Mimesis and Occult Modernism in Literature and Art Around 19002018 •

Bowdoin Journal of Art

The Future is Now: Hilma af Klint and the Esoteric Imagination2020 •

2019 •

in Marja Lahelma and Frances Fowles (eds), The Idea of North: Myth-Making and Identities

The North, National Romanticism, and the Gothic2019 •

The Harriman Review

The occult revival in Russia today and its impact on literature2007 •

Studia Humanistyczne AGH

THE ORIGIN AND IMPACT OF THE THEOSOPHICAL CENTRE IN ADYARJournal of Social and Development Sciences

The Library of Rudolf Steiner: The Books in English2018 •

A Modern Panarion: Glimpses of Occultism in Dublin

Barbarism or Awakened Vision? Art, Theosophy & Post-Impressionism in Dublin2014 •

A Mediated Magic: The Indian Presence in Modernism 1880-1930

Modernism's Muse2019 •

Spaces of Utopia

Art in the Fourth Dimension: Giving Form to Form–The Abstract Paintings of Piet Mondrian2007 •

RELATED TOPICS

- Find new research papers in:

- Physics

- Chemistry

- Biology

- Health Sciences

- Ecology

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

Massimo Introvigne

Massimo Introvigne