Maria Katharina Wiedlack

Queer Feminist Punk

An Anti-Social History

zaglossus

�Maria Katharina Wiedlack

Queer-Feminist Punk

An Anti-Social History

zaglossus

1

�2

�Maria Katharina Wiedlack

Queer Feminist Punk

An Anti-Social History

zaglossus

3

�Veröfentlicht mit Unterstützung des Austrian Science

Fund (FWF): PUB 241-V21

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliograie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://

dnb.dnb.de.

© Zaglossus e. U., Vienna, 2015

All rights reserved

Copy editors: C. Joanna Sheldon, PhD; Michelle Mallasch, BA

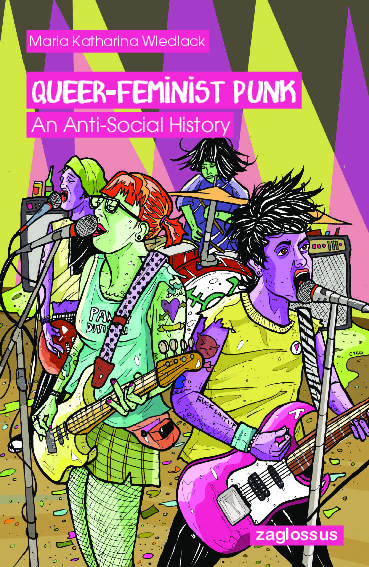

Cover illustration: Cristy C. Road

Print: Prime Rate Kft., Budapest

Printed in Hungary

ISBN 978-3-902902-27-6

Zaglossus e. U.

Vereinsgasse 33/12+25, 1020 Vienna, Austria

E-Mail: info@zaglossus.eu

www.zaglossus.eu

4

�Contents

1. Introduction

1.1.

1.2.

1.3.

1.4.

1.5.

Radically Queer

Anti-Social Queer Theory

The Culture(s) of Queer-Feminist Punk

The Meaning(s) of Queer-Feminist Punk

A Queer-Feminist Punk Reader’s Companion

2. “To Sir with Hate”:

A Liminal History of Queer-Feminist Punk Rock

2.1. “Gay Punk Comes Out with a Vengeance”:

The Provisional Location of an Origin

2.2. “Feminists We’re Calling You, Please Report to the

Front Desk”: The New Wave of Queer Punk Feminism

during the 1990s

2.3. “For Once, We Will Have the Final Say, [...] Cause They Know

We’re Here to Stay”: The Queer-Feminist Punk Explosion

2.4. “After This in the USA They Say You’re Dead Anyway”:

Queer-Feminist Punk Recurrences after 2000

2.5. “Punk May Not Be Dead, but It Is Queer ...”: Intersectional

Approaches in Contemporary Queer-Feminist Punk Rock

2.6. “Don’t Put Me in a Box. I’ll Only Crush It”:

Writing and Archiving a Movement

2.7. To Be Continued ...: A Preliminary Conclusion

3. “We’re Punk as Fuck and Fuck like Punks”:

Punk Rock, Queerness, and the Death Drive

9

13

18

20

23

27

30

34

57

63

67

71

76

85

89

3.1. “Pseudo Intellectual Slut, You Went to School, Did You

Learn How to Fuck?”: A Bricolage of Psychoanalytic Theories 91

3.2. Queer-Feminist Punk and Negativity

97

3.3. “Fantasies of Utopia Are What Get You Hooked on Punk in

the First Place, Right?”: Queer-Feminist Punk Rock,

Sociality and the Possibility of a Future

120

3.4. “So Fuck That Shit / We’re Sick of It”: Conclusion

143

5

�4. “Challenge the System and Challenge Yourself”:

Queer-Feminist Punk Rock’s Intersectional Politics

and Anarchism

146

4.1. “Anarchy Is Freedom—People before Proit”:

Queer-Feminist Punk Approaches to Capitalism

4.2. “Fuck the System / We Can Bring It Down”:

Gay Assimilation, Capitalism and Institutions

4.3. “Rebels of Privilege”?

Queer-Feminist Punk Hegemonies and Interventions

4.4. “Spit and Passion”:

The Queer-Feminist Punk Version of Anarchism

149

180

188

190

5. “There’s a Dyke in the Pit”:

The Feminist Politics of Queer-Feminist Punk Rock 193

5.1. “Not Gay as in Happy, but Queer as in Fuck You”:

Dykecore and/as Feminism

5.2. “You’ll Find Your Place in the World, Girl, All You Gotta Do

Is Stand Up and Fight Fire with Fire”: Queer Bonds and

the Formation of a Movement

5.3. “Oh, I’m Just a Girl, All Pretty and Petite”:

Queer-Feminist Punk Rock and Third-Wave Feminism

5.4. “Don’t You Stop, We Won’t Stop”: Conclusion

6. “A Race Riot Did Happen!”:

Queer Punks of Color Raising Their Voices

6.1. “All We Have Now to Wait to See / Is Our Monochrome

Reality”: Introduction

6.2. “Whitestraightboy Hegemony”: How Punk Became White

6.3. “Hey, Look Around, There’s So Much White”:

Early Role Models

6.4. “This Fight Is Ours”: Queer Punks of Color Visibility

within Queer-Feminist Punk Culture

6.5. “It Puts a Little Bit of Meaning into the Fun”: Punk,

(B)orderlands, and Queer Decolonial Feminism

6.6. “Rise Up—No One Is Going to Save You”: Queer-Feminist

Punks of Color and the Queer-Feminist Punk Revolution

6

195

238

256

263

266

266

272

282

292

305

322

�7. “WE R LA FUCKEN RAZA SO DON’T EVEN FUCKEN

DARE”: Anger and the Politics of Jouissance

326

7.1. “We Speak in a Language of Violence”:

The Aesthetics of Anger

7.2. “Smile Bigger Until You Fucking Crack”:

Anger, Jouissance and Screams

7.3. “Screaming Queens”: The Voice, the Body, and Meaning

7.4. “We’ll Start a Demonstration, or We’ll Create a Scene”:

The Creativity in Negativity

7.5. Not Perfect, Passionate: Conclusion

8. “We’ve Got to Show Them

We’re Worse than Queer”: Epilogue

8.1. “I Am Sickened by Your Money Lust / and All Your

Fucked-Up Greed”: Queer-Feminist Punk Occupying the US

8.2. Queer-Feminist Punk Goes International

8.3. ”... A Cover By a Band That No Longer Supports the

Message of Their Own Song”!?!

References

330

342

348

355

361

364

366

384

394

399

7

�8

�1. Introduction

This book presents a map and analysis of queer-feminist punk

histories that are located in the US and Canada. It ofers a very

detailed description of people, bands, events, and their politics.

Although the collection and analysis are deinitely a good read

for punk knowledge showofs or anyone looking for inspiration

to update hir personal countercultural collection, they are by no

means exhaustive. This work is limited by my “outsider” status as

a white European academic, as well as by my education and personal interests, and therefore should not be understood as universal or true for everyone. Hopefully, however, the book will appeal to queer-feminist punk “nerds,” academics and activists alike.

It ofers many insights into alternative strategies for queer-feminist political activism, and hints at alternative opportunities to

regroup and bond, experience pleasure and ight against oppressive structures. In addition, chapter three in particular provides

a good read for all academic dissidents who gain pleasure from

losing themselves in hardcore psychoanalytic theory. Chapter

three is not a must-read to understand the analysis of the queerfeminist punk material and of the social bonds created around

and through queer-feminist punk. However, I encourage readers

to follow me on my adventure through “the evil ways” of queer

theory. There might not be a bright future awaiting the traveler

at (death) the end of the journey, but there could be something

unexpected or important in store.

With this book I ofer a historiography that starts in the mid1980s, highlighting Toronto’s queer-feminist punk dissidence as

one origin. However, there might be diferent versions of queerfeminist punk’s emergence. It relects my journey through tons

9

�of queer-feminist punk lyrics, tunes, zines, academic articles and

books, as well as the unforgettable impressions gathered during

endless nights in the middle of (queer-feminist) mosh pits, and

bits and pieces of irsthand information from discussions with musicians, organizers and activists. In other words, this historiography is highly subjective and aims to provoke dialogue—or better

yet, have others tell their version of queer-feminist punk history.

Queer-feminist punk has many beginnings, and although this

book tells exciting punk stories, they are not the only ones. Moreover, the histories of queer-feminist punk are often entangled

with other histories and movements that inhabit punk’s centers

and margins, and leftist punk scenes and circles in general. Although this entanglement must be acknowledged and indeed

highlighted, this book puts queer-feminist and anti-racist politics

at the center of punk rock’s history. It focuses on the individual

bands, musicians, writers and organizers, whose politics and productions usually relect the margins of the punk culture they inhabit according to the punk literature. This book seeks to bring

queer-feminist punks of color, riot grrrls and queercore, homocore or dykecore to the fore and map out their political and performative agendas, strategies and methods. Following contemporary queer-feminist anti-racist punk scholars like Fiona I. B. Ngô

and Elizabeth A. Stinson (“Introduction: Threads and Omissions”),

Mimi T. Nguyen (“Riot Grrrl, Race, and Revival”) or Tavia Nyong’o

(“Do You”), this book proposes that queer feminists and punks of

color as well as the politics around racialization and non-normative genders, sexes, and sexualities have always been important

parts of punk culture and that it is time to complicate the picture,

rather than renarrate the straight punk history of white middleclassness, homophobia and racism again and again.

By focusing on queer-feminist punks and queer-feminist punks

of color within punk rock history, I also subsume many individuals

and groups under the label queer-feminist punk that might use or

reject diferent labels like queercore, homocore or dykecore, as well

as riot grrrl or Afro-punk. Despite their diferent labels, and selfidentiications, as a whole the individual protagonists, scenes, as

10

�well as their artistic and political discourses, share important politics and strategies. Accordingly, I argue that queer-feminist punk

countercultures belong to or form a political movement and that

their productions—lyrics, writing, sound and performances—

should be seen as a form of queer-feminist activism and agency.

Furthermore, I propose that queer-feminist punk countercultural

agents do not only engage with queer and feminist politics, as

well as with academic theory, but also produce queer-feminist

political theory—a more or less coherent set of ideas to analyze,

explain and counter oppressive social structures in addition to

explicit open violence and oppression. The focus on queer-feminist anti-racist punk politics within punk rock is not only an attempt to rewrite punk and riot grrrl history but, to use the words

of Ngô and Stinson (170), also an attempt to “expand the places

where we ind valuable knowledge, to re-imagine who counts as

an intellectual producer, and to work across genres.” My use of

the term queer-feminist politics—rather than queer politics—is inspired by the tradition of many activists around the world who

call attention to the still prevalent sexism, misogyny and inequality in mainstream cultures, including queer movements, by foregrounding the feminist aspects of their queer politics. More recently, similar politics have found their way into academic writing,

for example, through the work of Mimi Marinucci,1 José Muñoz,2

Judith Jack Halberstam,3 and others. Such activist and academic approaches conceptualize queer politics as a continuation of

feminist movements and theory rather than as a revolutionary

1

2

3

Feminism is Queer: The Intimate Connection between Queer and Feminist

Theory. London: Zed Books, 2010.

In particular, the books Disidentiications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999)

and Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York: New

York University Press, 2009) by José Muñoz are from a decidedly feminist and queer perspective.

Halberstam explains her feminist take on queer theory strongly in her

books, In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives

(New York: New York University Press, 2005) and The Queer Art of Failure

(Durham: Duke University Press, 2011).

11

�break with them. Furthermore, they seek a dialogue between lesbian and gay movements, second-wave feminists and the diverse

range of queer movements to build alliances and diferent forms

of solidarity.

My examples of queer-feminist punk rock activists also seek to

ind alliances with diferent groups of queer, feminist and decolonial thinkers and activists. These groups and their allies understand the usefulness of queer, feminist and decolonizing politics,

activist strategies and social analysis against the racialized discrimination, misogyny, homophobia, ableism and transphobia of

mainstream culture as well as the countercultural environments

of punk rock and queer scenes. They combine feminist and decolonial accounts with their speciic punk philosophy of anti-social

queerness or queer negativity. By analyzing lyrical content, writing, music, sound, performances and countercultural settings in

general, I provide examples of queer-feminist anti-social accounts

of punk music (e.g., expressions of negativity and anger) and argue that queer-feminist punk rock as such can be understood as

a politics of negativity. Relating such queer-feminist punk negativity to academic concepts and scholarly work, I show how punk

rock is capable of negotiating and communicating academic

queer-feminist theoretical positions in a non-academic setting.

Moreover, I argue that queer-feminist punk not only negotiates,

translates and appropriates academic approaches, but also produces similar negative and repoliticized queer-feminist theories

without any direct inspiration from academic discourses.

Taking queer-feminist punk countercultural discourses seriously, I furthermore argue that queer-feminist punk communities accomplish what academic queer theory following the “anti-social

turn”4 often does not achieve: They transform their radically antisocial queer positions into (models for) livable activism. Moreover,

they form social bonds through queer negativity that exceed normative forms of relationality.

4

12

Halberstam, “The Anti-Social.”

�1.1. Radically Queer

Considering contemporary usage of the term queer in the area

of theory as well as political activism, I claim that queer-feminist

punk ofers a perspective on queerness as well as models for

queer and feminist critique and social activism, which are able to

counter the ongoing inclusion of queerness in neoliberal capitalism. Such politics are able to reactivate the radical potential that

the term and concept queer used to have in earlier times.

From a historical perspective, the term queer emerged on

the landscape of political discourse and activism in the 1990s

as a counterposition or intervention. It was a term of resistance

against oppression and a statement for radical social change.5 “It

was a term that challenged the normalizing mechanisms of state

power to name its sexual subjects: male or female, married or

single, heterosexual or homosexual, natural or perverse,” as the

scholars David Eng, Judith Jack Halberstam and José Muñoz emphasize in their article, “What’s Queer About Queer Studies Now?”

(1). For example, the word queer in the name Queer Nation—the

radical AIDS activist group known for appropriating the term as a

provocative self-reference irst—“highlight[s] homophobia in order to ight it” (4), as Robin Brontsema points out.

When theorists imported queer as a theoretical concept into

the academy in the 1990s, they aimed for a similar efect—to

challenge norms. Teresa de Lauretis was the irst documented

scholar to use the term queer theory in an academic setting. David Halperin recalled de Lauretis’s intention in her use of “queer” in

his article, “The Normalization of Queer Theory”:

[She] coined the phrase “queer theory” to serve as the

title of a conference that she held in February of 1990

at the University of California, Santa Cruz [...]. She had

heard the word “queer” being tossed about in a gayairmative sense by activists, street kids, and members

5

Cf. Shepard 512; Brontsema 4.

13

�of the art world in New York during the late 1980s. She

had the courage, and the conviction, to pair that scurrilous term with the academic holy word, “theory.” Her

usage was scandalously ofensive. [I]t was deliberately

disruptive. [S]he had intended the title as a provocation.

She wanted speciically to unsettle the complacency of

“lesbian and gay studies.” (340)

I want to call attention to Halperin’s interpretation of de Lauretis’ motives as “provocation” and “deliberately disruptive.” He suggests that de Lauretis used queer theory to reject dominant gay

and lesbian identity politics as well as academic approaches that

focus on sexuality as a stable identity category. Halperin’s anecdote indicates that queer theory was once seen as a promising

and radical political intervention in the production of knowledge

and meaning, social structures and institutions. Moreover, it implies that the concept of queer emerged within countercultural

spheres and activism, among “street kids” and “the art world” during the 1980s and was introduced into academia only afterwards.

The successful incorporation of the term queer into the language of capitalism, the promotion of lifestyle products, the concept of metrosexuality, however, speaks to the deradicalization

and depoliticization of queerness in such contexts, as well as the

lexibility of capitalist heteronormative patriarchal power structures. Its introduction into commercial entertainment through

the late 1990s and the 2000s—for instance, in shows like Will &

Grace,6 Queer Eye for the Straight Guy,7 or The L Word8—equally

6

7

8

14

Will & Grace was a US television sitcom about a successful New Yorkbased gay lawyer called William Truman and his straight female friend

Grace Adler, a successful designer. The sitcom was produced by James

Burrows and NBC Studios and aired from 1998 to 2006 for a total of

eight seasons. It was arguably one of the most successful sitcoms with

gay characters in the history of television.

Queer Eye for the Straight Guy was a US reality television series on the

Bravo cable television network from 2003 to 2007, produced by David

Collins, Michael Williams and David Metzler (Scout Productions).

The L Word was a US television drama series on the cable channel

�furthered the process of depoliticization. Such corporate media

representation of gays and lesbians created mainstream perceptions of queerness as non-threatening, successful, beautiful and

predominantly white and, most important, compliant with capitalist consumer logics. Shortly following the annexation of the

concept in academia, a deradicalization of the term queer within

the mainstream became apparent and both, being queer as well

as using the term queer, became normalized within the academic

landscape. The incorporation of queer theory in gender studies

programs, the numerous queer studies and queer theory readers by commercial publishing companies such as Routledge,9 Palgrave MacMillan10 and Blackwell Publishing11 as well as the establishment of queer theory book series such as Series Q by Duke

University Press mark such processes of absorption and deradicalization of queer within the mainstream academic ield. Resisting

that end, my analysis here aims to “ind ways of renewing [queer’s]

radical potential” (343), to borrow Halperin’s words again. I argue

that the appropriation and use of the term queer within queerfeminist punk rock is an approach that has the radical potential to

resist the ongoing inclusion of gay and lesbian identities in mainstream discourses and consumer culture, the transformation of

gay and lesbian identiication into a lifestyle choice as well as a

legal category. Moreover, queer-feminist punk rock uses the term

queer to counter the process of queerness becoming an identity category itself. A validation of countercultural queer theory, as

Showtime that ran from 2004 to 2009. The series was produced by Ilene

Chaiken, Michele Abbot, and Kathy Greenberg and originally portrayed

the lives of a group of lesbians, and bisexuals, their families and partners. During the six seasons, one transgender and a couple of more

luidly sexual-identiied protagonists were added. The cast consisted of

exceptionally gender normative, tall, conventionally beautiful, predominantly white, rich people. The location is West Hollywood.

9 Hall, Donald E. and Annamarie Jagose, eds. With Andrea Bebell and Susan

Potter. The Routledge Queer Studies Reader. New York: Routledge, 2012.

10 Morland, Ian, and Annabelle Willox, eds. Queer Theory. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

11 Corber, Robert J., and Stephen Valocchi, eds. Queer Studies: An Interdisciplinary Reader. Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 2003.

15

�in my example of queer-feminist punk rock within academic discourses, could halt the process of academic queer theory becoming normative. This research could participate in developing “a renewed queer theory” (Eng, Halberstam, and Muñoz 1)—a queer

theory that necessarily needs to understand sexuality as “intersectional, not extraneous to other modes of diference, and calibrated to a irm understanding of queer as a political metaphor

without a ixed referent” (ibid.). In other words, my project presents theories and approaches within the countercultural sphere

of punk rock in which queer still has the political potential to irritate and resist neoliberal incorporation, and reject oppression. In

addition, it presents countercultural concepts “for diferent ways

of being in the world and being in relation to one another than

those already prescribed for the liberal and consumer subjects,” as

Halberstam puts it in the recent book The Queer Art of Failure (2).

I argue that queer-feminist punk countercultures produce queerfeminist theory that is neither less sophisticated nor less valuable

than academic approaches.

Furthermore, contrary to much of academic theory, the theoretical approaches developed within the queer-feminist punk

movement have a strong connection to the everyday life of its

participants.12 Within the countercultural sphere of queer-feminist punk rock, “the divisions between life and art, practice and

theory, thinking and doing” are not clear-cut, but luid or “chaotic,” according to Halberstam (ibid.). Accordingly, theory is not just

a product of cognitive and emotional processes, the processes

themselves must also be understood as theory. Following the anarchists among the queer activists and scholars, such as Benjamin

Shepard, theory does not just inluence practice, both aspects are

inseparable within queer activism (515). Theory is a doing, a practice and “the understanding of human practice” that becomes “directly lived,” as Guy Debord emphasizes in The Society of the Spectacle (qtd. in Eanelli 428). To account for both the processes and

products of knowledge production and distribution, the term

12 Cf. McLemee; Rogue and Shannon; Klapeer; Rauchut.

16

�and concept of theory itself needs to be reworked for the purpose of my investigation.

To contribute to the broader academic discussion within the

ield of queer studies, I contrast references from theorizations of

the countercultural sphere of queer-feminist punk rock with academic queer theory. The forms of theorized resistance against

hegemonic logic that seem most promising to me, as mentioned

above, are the places of the radically queer. Radical queer theories can be found in both academia and countercultures. Such

accounts, as I understand them, are theories that refuse and reject complicity with neoliberal consumer and heteronormative

cultures. In other words, I focus on the irritating, the disturbing,

and the unsettling. Moreover, in combining the academic with

the countercultural, I aim to develop a new, radical theoretical approach dedicated to dismantling oppressive power structures in

their full complexity.

As I argue throughout my analysis, queer-feminist punk rock

can be seen as one of the most radically queer countercultural

spheres or movements of resistance against heteronormative

knowledge production. The intersectional politics of resistance

that queer-feminist punks use are anti-social queer politics. Such

politics show interesting parallels with recent developments in

queer theory that have become known as anti-social queer theory. Moreover, the embrace of negativity connected to the word

queer within punk rock was an anticipation of queer as anti-social

even before academia “jump[ed] on the negativity bandwagon,”

in the words of queer anarchist Tegan Eanelli (428), a position taken also by queer theorists such as Halberstam,13 Nyong’o,14 and

Muñoz.15 Although radical queer-feminist activists such as Eanelli

disdain academic anti-social queer theory, I see potential for the

radical irritation of hegemonic discourses in the corpus of academic queer theory that Judith Jack Halberstam framed as the

“Anti-Social Turn in Queer Studies.”

13 Halberstam, “The Anti-Social”; “The Politics”; The Queer Art.

14 “Do You.”

15 Disidentiications.

17

�1.2. Anti-Social Queer Theory

As a theoretical concept, the anti-social turn is informed by psychoanalytic—mostly Lacanian—concepts of sexuality. Following

queer psychoanalytic approaches, such as those of Leo Bersani,16

sex is understood as anti-communicative, destructive, and antiidentitarian. One of the most inluential theorists following this

development of queer theory is the American literary theorist

Lee Edelman in his book No Future: Queer Theory and the Death

Drive. Edelman’s book posits that sexuality in our symbolic order

marks the irritation of the self as in control, whole and autonomous. In other words, sexuality and sexual acts irritate the constant construction of identity and autonomous agency. To integrate sexuality successfully into the illusion of an autonomous

self, it must be attached to the purpose of reproduction. Consequently, queerness in this logic can only signify the opposite of

creation and reproduction or “the place of the social order’s death

drive” (No Future 3). What constitutes and structures queerness as

a meaningful term, according to Lee Edelman, is not its relation

to queer desire but to “jouissance” (ibid.). Jouissance is “the painful pleasure of exceeding a law in which we were implicated, an

enjoyment of a desire (desir), in the mode of rage or grief, that

is the cause and result of refusing to be disciplined by the body

hanging from the gallows of the law,” to use the words of psychoanalytic theorist Elizabeth Povinelli (“The Part” 288). I read the law

Povinelli mentions and which jouissance exceeds as the symbolic

order of meanings, as well as social rules and regulations—everything that signiies certainty, familiarity and safety. However, as

potentially radical or dismantling as Edelman’s theory is, it also

precludes any possibility of political activism. Moreover, Edelman

argues that queerness is not only the opposite of society’s future,

but also the opposite of every form of politics.

Nevertheless, many queer scholars airm and rework anti-social

psychoanalytic queer theory as politics. Judith Jack Halberstam,17

16 Bersani, Leo. Homos. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995.

17 “The Anti-Social.”

18

�Elizabeth Povinelli,18 Tavia Nyong’o,19 and José Muñoz20 hold on to

the political potential in anti-social queerness. They criticize Edelman’s account for its “inability to recognize the alternative sexual practices, intimacies, logics, and politics that exist outside the

sightlines of cosmopolitan gay white male urban culture” (Rodríguez, “Queer Sociality” 333). My work tries to connect multiple

anti-social queer theories and criticism. I merge diferent antisocial academic accounts to develop a theoretical account that

has the potential to criticize and resist hegemony. In addition, I

combine and extend anti-social queer theories with works by the

black feminists bell hooks and Audre Lorde to argue that their theorization of anger allows for a thinking through of anti-social and

queer at the intersection of racialization. Moreover, a focus on anger enables us to extend our analysis of anti-social queer politics

from the realm of symbolic meaning to the realms of the corporeal

and afective: action, feelings, experience and the body.

I relate such diferent academic accounts to queer-feminist

punk movements to establish a dialogue between both ields and

enrich them in terms of their ability to resist the deradicalization

of queer theory critically. To do this, I use academic psychoanalytic accounts to analyze queer-feminist punk productions and the

social relations they create and circulate within, as well as to make

queer-feminist punk productions more comprehensive to an audience unfamiliar with punk rock conventions. By making connections between academic theory, countercultural productions

and social spaces, I aim to gain attention and interest from activists of the countercultural movement of punk rock who might not

necessarily relate well to the machinery of academic knowledge

production.

18 Povinelli, “The Part.”

19 “Do You.”

20 Disidentiications.

19

�1.3. The Culture(s) of Queer-Feminist Punk

The ield, or object of my research, as I have already frequently

mentioned, is queer-feminist punk rock produced by US-based

queer- and punk-identiied musicians, writers and community organizers of the mid-1980s until today. I relect on the particular

countercultural movement in connection with the broader sociopolitical and cultural environment of the US. In chapter two, I

show that the queer-feminist punk movement emerged in reaction to the political and social US-speciic discourses on homosexuality, gender, HIV/AIDS and racialization between the late 1970s

and early 1980s. I give examples of how queer-feminist punks analyzed those discourses and formed their political resistance accordingly. Moreover, by analyzing the political themes and agendas of the queer-feminist punk movement’s historical overview

until today, I show that activists broadened their initial focus to

analyze and resist US-American hegemonic discourses such as

colonialism, neoliberalism and globalization.

Although I insist on the term counterculture to describe the

queer-feminist punk movement, I want to emphasize again that

the movement does not disassociate itself from the rest of US society. On the contrary, even though they reject US cultural and

political hegemony, queer-feminist punks actively establish a dialogue with other oppressed people in the US. They build alliances

and community far beyond the limits of their own countercultures. The results of such initiatives can be seen in the reactions

of countless fans of queer-feminist punk rock who describe their

experience of the music, the writing and art as crucial to forming their queer identities, developing self-esteem and becoming

political. Moreover, the long-lasting efect of queer-feminist punk

politics can be seen in the over 30-year existence of the movement and communities, as well as in the punk activities within

other social movements, which I discuss in the inal chapter.

I want to underscore again that the countercultural sphere of

queer-feminist punk rock is not restricted by deinite borders,

therefore it is quite luid; however, the music, writing and social

20

�scenes I designate as queer-feminist punk are connected in a multitude of ways. First, queer-feminist punk productions are connected through their politics. Some are also connected through

explicit verbal references, while others relate through an identiication with riot grrrl, queercore or homocore, and dykecore; some

bands, writers, organizers and scenes are connected through mutual projects as well as personal friendships. In addition, in close

relation to their shared politics they are also connected through

their musical style via punk rock.

Although I want to emphasize punk rock in queer-feminist

punk, this musical style is by no means clearly deined. Punk in

queer-feminist punk rock is as luid and anti-identitarian as queerness. It clearly exceeds conventional deinitions of punk music as

based on three chords, simplicity or amateurism. Beyond, or in

close connection with the musical style, I argue that the word and

concept punk is deined through negativity and anti-social politics. On the broadest level, queer-feminist punk means to “question everything, [to] take nothing as given [...] even if it doesn’t

win me social points. [A] constant thinking and talking about

privilege, fucked up social structures, refusing to let people get

away with bigotry,” says punk writer Jessica Skolnik (“Modernist

Witch”). This does not mean that style is not important. On the

contrary, as I show in chapters two and three, punk style—the

music’s speed, high volume, DIY character and aggressive performances—corresponds to the outspoken anti-social behavior, liberating verbal violation of rules and embrace of outsider status

of its followers, all of which are crucial for queer-feminist punk

politics. Queer feminists understand the elements of punk to be

potent strategies to articulate their discontent and anger about

contemporary society. Punk translates the symbolic rejection of

society from the standpoint of an outcast and the airmation

of this negative status into sound. Nevertheless, punk’s style or

“noise,” as Dick Hebdige described it in his seminal work Subculture: The Meaning of Style, is not limited to deined norms of punkness. After all, if there were rules that were strictly adhered to, it

would not be punk.

21

�The starting point for this investigation into the countercultural sphere of queer-feminist punk is an understanding of its productions—music, zines and other types of expression—as ways

to produce meaning and active, political intervention into hegemonic power structures following the cultural-studies approaches of Stuart Hall and Tony Jeferson,21 Dick Hebdige,22 and George

Lipsitz.23 Moreover, I understand queer-feminist punk communities, concepts and ideas, as well as their cultural productions to be

entities connected through a political movement. The concept of

a movement emphasizes this connection between queer-feminist

punks and their output on a discursive level. In other words, calling queer-feminist punk a movement suggests a meta-connection between the various cultural productions, their politics and

the multiple social scenes in which they circulate. I theorize queerfeminist punk as a movement in order to emphasize its forms and

products as activism or doing. In addition, the idea of a movement

emphasizes the connection between hegemonic culture, location

and time. It allows us to see similarities and diferences between

individuals and groups, as well as their social structures, political

views and methods. The similarities that bind individuals together

in this movement are the strategies they use—the musical style,

the ofensive language, the self-made prints and records—as well

as the anti-social understanding of queerness and punkness, and

the rejection of US hegemony. While the strategies and styles of

diferent groups and individuals are not exactly the same and the

political issues vary as well, core topics can be identiied throughout the thirty years of the movement’s existence. In particular, the

politics have changed over time, in keeping with the broader socio-political context within the US and beyond. Moreover, queerfeminist punks address individual and structural diferences of

21 Hall, Stuart, and Tony Jeferson, eds. Resistance through Rituals: Youth

Subcultures in Post-War Britain. London: Routledge, 1976.

22 Subculture.

23 Lipsitz, George. “Cruising around the Historical Bloc: Postmodernism

and Popular Music in East Central Los Angeles.” Cultural Critique 5 (1986):

157–77.

22

�experiences and politics themselves. They do not share a group

identity for the most part. Hence, the notion of a movement alludes to processes of change over time, to diferences among individuals and groups as well as to the fact that people are bound

together through their political agenda rather than their personal

identity. My analysis aims to relect this continuation and change

by showing the stringency of key concepts within queer-feminist

punk throughout its history as well as the changes and shifts in

meanings, forms and activities over time.

1.4. The Meaning(s) of Queer-Feminist Punk

To account for the multilayered meanings, strategies and politics

of queer-feminist punk rock throughout history, I will irst explain

what the forms or styles of queer-feminist punk rock look like and

who the performers of queer-feminist punk are in chapter two.

Based on the assumption that cultural products of queer-feminist punk rock and especially their style have political and social

relevance, I will lay out what the politics of queer-feminist punk

are and explain their intersection with contemporary academic

queer theory. I will then address the purpose of the appropriation

of queer as well as punk.

I want to highlight that queer-feminist punk movements create

political, social and cultural theory. Nevertheless, they often do so

in exchange with other queer activist movements and communities as well as scholarly research. Moreover, I agree with Judith

Jack Halberstam that it might be time to rethink the perception

of “the academy” and “the counterculture” (The Queer Art of Failure 7–15). Queer activists are often students, researchers or even

faculty members of universities. Hence, not only has academic

queer theory inluenced countercultural spheres but sometimes

also developed within those countercultural spaces through academics as well as non-academics. In addition, queer-feminist activism has intervened in multiple cases in discourses on academic territory. Thus, my account difers signiicantly from scholarly

23

�views that suggest queer theory has lost its social relevance in

recent years.24 Nevertheless, it needs to be emphasized that academia follows a set of norms and rules that do not allow for total

invasion by queer-feminist countercultural protagonists like punk

rock musicians. Academia’s administrative, legal and social apparatus does not allow for a total deconstruction through queer theory. Accordingly, I argue that queer-feminist countercultures have

a greater potential for radical resistance than academia can ever

have, because becoming part of academia requires a great deal

of self-disciplining, assimilation and normativity in the irst place.

In other words, to become resistant to academia, the individual

has to assimilate her or himself to academic norms irst. These

norms are patriarchal, capitalistic and mostly white. Although the

US and its apparatus as well as its social conventions and norms

oppress queer-feminist punks, its hegemonic power and survival

demands assimilation.

My research argues that the social structures of both academia

and queer-feminist punk rock need to be understood as highly intersectional. Since they are hardly separable from each other, an

analysis of their speciic intersections is needed. I have chosen the

range of academic queer and feminist theories and queer-feminist

punk theories, productions and politics because they either parallel the discourses of my research material or were explicitly mentioned in queer-feminist punk productions. Consequently, my approach can be understood as a bottom-up approach starting from

countercultural phenomena to academic theory. As already suggested, the theories applied are mainly, but not exclusively, antisocial queer theories.

Queer-feminist punk’s production of meaning and knowledge

must be located on various levels: textual, oral, performative and

emotional. Apart from being intersectional, it changes over time.

Consequently, my project is highly interdisciplinary in its usage

of not only theories but also methods. The assemblage of diferent theoretical approaches and analytical instruments at play

24 Cf. McLemee; Rogue and Shannon; Klapeer; Rauchut.

24

�can best be addressed with what Judith Jack Halberstam calls a

“queer methodology” (Female Masculinity 10). It combines “textual criticism, ethnography, historical survey, archival research,

and the production of taxonomies” (ibid.). Such a methodology is

“queer because it attempts to remain supple enough to respond

to the various locations of information” and, furthermore, “betrays a certain disloyalty to conventional disciplinary methods,”

as Halberstam explains (ibid.). Large parts of my analysis deal

with cultural artifacts—especially writings and oral expressions,

like lyrics and interviews—and their meanings. Accordingly, the

method most frequently used throughout my analysis can be

termed semiotic, as developed by cultural studies scholars. For

the purpose of my analysis, the most important punk researcher

is Dick Hebdige. His thesis, formulated in 1979, maintains that

countercultures afect hegemony through style-inluenced decades of semiotic analysis of countercultural productions. Moreover, his research was well-received by punks themselves and

therefore inluenced their understanding of style as resisting.

Following Hebdige, as well as more recent queer theory scholars like Halberstam, Driver, Muñoz and Ngyong’o, I investigate

queer-feminist punk style at the intersection of political agency, knowledge production and social relevance. Including writings about queer-feminist punks’ experiences, especially with

their community, and data gathered through interviews, as well

as participant observation, I analyze how queer-feminist punk

communities translate their political values and theories into

social practice. To explain the forms of community that emerge

through the politics of negativity, I use Jean-Luc Nancy’s25 theorizations on counter-hegemonic concepts of social bonds.

The analytical theory used for the interpretation of my examples is

mostly, but not exclusively, informed by the queer psychoanalytic

work that I described earlier. Inspired by queer-feminist punk rock’s

25 Nancy, Jean-Luc. Being Singular Plural. Stanford: Stanford University Press,

2001.

25

�use of the term queer as anti-social, I read contemporary anti-social queer theory against a selection of representative queer-feminist punk lyrics. Furthermore, I use Edelman’s account of the queer

as anti-social and opposed to futurity and “the Child” (No Future

3) to explain why queer-feminist punk rock refers to queerness

as anti-social. To do this, I read queer-feminist punk lyrics against

Edelman’s account to show that the theorization of queerness as

anti-social in queer-feminist punk predated his own. However, using the psychoanalytic work of Elizabeth Povinelli, I argue that the

value of such politics does not necessarily remain in the deconstruction of existing meanings, values and social relations. On the

contrary, referring to Judith Jack Halberstam,26 Elizabeth Povinelli27 and Antke Engel,28 I suggest that the value of queer-feminist

punk’s politics of negativity lies in its potential to create queer social bonds that are able to resist heteronormative logic.

Queerness, however, is not the only issue that queer-feminist

punk lyrics and literature address. In the course of a detailed reading of selected lyrics and writings, I enumerate and discuss the

various issues that queer-feminist punks address and show that

queer-feminist punk rock theorizes and communicates the interdependency of categories and forms of oppression. In addition,

I account for the intersectional approaches in my queer-feminist

punk examples by applying contemporary queer theory to explain

the interconnections of categories such as sexuality, class, gender,

bodily ability and race (e.g., José Muñoz, Juana Maria Rodríguez,

Jasbir Puar, Amit Rai, and Dean Spade). In referring to such works,

I make a connection between the production of meaning, social

relations and institutional oppression.

In analyzing queer-feminist appropriations of feminism and

their relationships to other feminist movements, I draw on the

works of Judith Jack Halberstam (In a Queer Time and Place),

26 “The Anti-Social”; The Queer Art of Failure.

27 “The Part.”

28 Engel, Antke. “Desire for/within Economic Transformation.” e-lux journal

17 (June/August 2010).

26

�Rebecca Walker and Ann Cvetkovich. In connection with queerfeminist punks, and anti-racist and decolonial politics, I draw on

a corpus of cultural studies approaches to punk rock that are not

necessarily queer, such as texts by Hebdige and Frith.

In addition, I focus on the intersection of queer-feminist punk’s

politics by closely analyzing its complex deployment of anger.

Furthermore, I refer to text references in queer-feminist punk writing by black feminists like bell hooks and Audre Lorde through an

analysis of such discourses and create a fruitful dialogue between

them and contemporary cultural studies approaches by Halberstam, Nehring (Anger) and others. I try to explain the position that

queer-feminist punks of color inhabit within their scenes by drawing on the concept of “third space” as developed by scholars like

Homi Bhabha, as well as that of “borderlands” by Gloria Anzaldúa.

I also elaborate on the relationships between queer-feminist

punks of color and their peers by drawing on the concept of decolonizing politics by Laura Pérez.

1.5. A Queer-Feminist Punk Reader’s

Companion

The following quick overview of each chapter is my attempt to

provide a navigation system through the myriad paths of my

work. Each chapter—although connected to the others—has a

meaning and story of its own and can be consumed accordingly. I

start my project by giving a historical overview of bands, communities, and some of their cultural productions in chapter two. The

overview is by no means exhaustive, but can be considered as the

irst collection of bands, subcultures, cultural productions and

collective initiatives accounting for the heterogeneity and diverse

political agendas contained within this “scene.” I relect on the

current state of research on queer-feminist punk to point to the

necessity of broadening the research focus from queer-feminist

politics to their intersection with anti-racist, decolonial, anarchist

and disability politics. Such a broadening is necessary not only to

27

�do justice to queer-feminist punk activism but also to disrupt the

notion of a strictly white male countercultural archive. In other

words, I collect or assemble queer-feminist punk productions to

contribute to the existing anti-social queer archive that theorists

such as Lee Edelman and Leo Bersani have established through

their analytical work. Moreover, I want to challenge the archive

that “oddly coincides with the canonical archive of Euro-American literature and ilm,” as Judith Jack Halberstam emphasizes

(“The Anti-Social” 152), and expand its focus from “a select group

of anti-social queer aesthetes and camp icons and texts” (ibid.)

to my diverse collection of countercultural protagonists and their

cultural productions. Incorporating queer-feminist punk into an

academic archive, however, is also an act of normalization. I address this problem in chapters two and four.

Chapter three distills hardcore theories from queer-feminist

punk music through a semiotic analysis of queer-feminist punk

lyrics, sound and performance. I argue that queer-feminist punk

politics of negativity can be found at the level of verbal expression as well as within sound and embodied performance and that

such performatives irritate heteronormativity, experience of time

and social relations. Moreover, I argue that anti-social queer-feminist punk politics have the potential to establish non-normative

social bonds.

In chapter four, I focus on queer-feminist punk politics as an

intersectional critique of oppression. Queer-feminist punks address and analyze the intersections of social, political and institutional oppression and oppressive concepts such as the state,

capitalism and white hegemonic power. Interestingly, the rejection of the plethora of intersecting hegemonic discourses of class,

gender, race and sexuality is often labeled anarchy. I show how

such anarcho-queer politics are formulated, what they address

and what their aim is.

In chapters ive to eight, I focus on various speciic issues that

queer-feminist punks address through their intersectional anti-social politics. In every chapter, I exemplify aspects of feminist politics, antiracism, and critical whiteness approaches by referring to a

28

�corpus of lyrics, as well as to the eforts of bands and communities.

Nevertheless, it must be emphasized that a queer-feminist punk

politics of negativity is intersectional, and that the examples I present are not necessarily representative of a single band, its products or communities as such, but rather of a speciic aspect of the

band’s politics. In other words, queer-feminist punks can hardly be

reduced to only one political agenda. The agendas I address are

more or less separate products of my foci or interests.

In chapter ive, I address the feminist politics of anti-social,

queer-feminist punk rock. In chapter six, I discuss white hegemony within queer-feminist punk communities and highlight some

crucial interventions by queer-feminist punks of color. Chapter

seven continues the focus on anti-racist, anti-privilege and decolonial interventions by queer-feminist punks within their communities, and addresses the meaning and use of anger. I propose

that queer-feminist punks’ appropriation of anger represents

a new facet or instantiation of anti-social queer-feminist punk

politics from the perspective of people of color. On a theoretical level, such accounts suggest that black feminist examinations

and appropriations of anger could add important insights to the

archive of anti-social queer theory. In the inal chapter, I briely

summarize the most signiicant results of my study. Moreover, I

come back to the question of how queer-feminist punk activism

forms alliances across countercultural, musical and national borders. I show how queer-feminist punk activists engage with the

larger society in the concrete context of the contemporary Occupy Wall Street and Occupy Oakland movements and briely analyze the readings of the latest Free Pussy Riot solidarity actions by

transnational alliances. These examples highlight the efect that

queer-feminist punk movements have beyond the limits of their

countercultural spheres and prove that the production and distribution of queer-feminist, anti-capitalist and decolonial punk

knowledge transgress mainstream values.

29

�2. “To Sir with Hate”:29

A Liminal History of

Queer-Feminist Punk Rock

“We’re punks.

We should be taking the piss out of the past.”30

This chapter gives an overview of the last three decades of queerfeminist punk bands, zine writers, record labels, events, and other

cultural productions. It shows that queer-feminist punk was signiied through anti-social politics, and the politics of queer-feminist negativity from its emergence in the 1980s onward and that

the movement is still informed by such politics. Considering the

vast number of bands, communities, productions and artwork, as

well as their sometimes short-lived existences or rootedness in

speciic localities, this collection is by no means complete. However, the chapter provides a view of a broad spectrum of activities

and people, by highlighting some of the most interesting cultural

29 The title To Sir with Hate was the title of the irst LP of the band Fifth Column in 1985 (Bruce LaBruce qtd. in Rathe 1). Fifth Column was a feminist, anti-patriarchy hardcore punk band from Toronto. The band members included G.B. Jones and Jena von Brucker. The term ifth column

refers to clandestine groups who try to undermine, deconstruct and

sabotage social institutions like nations from within. The term was often

used to refer to anarchist groups during the Spanish Civil War (Encyclopedia Britannica. Web. 10 May 2012. <http://www.britannica.com/>).

30 This quote is from Carolyn Keddy’s punk column “Bring Me the Head

of Gene Siskel” in Maximumrocknroll 347 (April 2012). Keddy urges the

contemporary punk community to critically relect on the forms of oppression and hegemonies in and throughout past punk communities.

30

�productions of queer-feminist punk. Moreover, the collection assembled here is probably the irst historical overview that covers

the diversity and intersectionality of queer-feminist punk productions and protagonists beyond speciic scenes, groups or historic

periods. In addition, it is the irst queer-feminist punk documentation that focuses on the issues and agendas of queer-feminist

punk, and their politics in general, from an intersectional perspective, which goes beyond an exclusive focus on representations of

queer and feminist identiications and politics. It highlights not

only queer-feminist punks of color, disabled, genderqueer or

working-class identiied punks but also focuses on anti-capitalist,

anti-racist, decolonial, anti-ableist and genderqueer anti-social

politics.

First, I will introduce the very irst people who explicitly fostered

queer-feminist punk politics with the labels homocore and queercore. I will briely describe those terms and explain why queerfeminist punks created the labels that refer to their bands and productions. Despite queer-feminist punks’ self-identiication as or

with queercore and homocore—especially during the late 1980s

and early 1990s—I decided to use the phrase queer-feminist punk

rock instead. I made this choice because the terms queercore and

homocore seem too limited to account for the diversity of politics signiicant for the movement. Moreover, the expression queerfeminist punk accounts for the fact that not all bands, writers and

artists who fall under the broader spectrum of anti-social queerfeminist punk politics identiied with the labels queercore or homocore. Some, for example, preferred the term riot grrrl. Hence,

I use the phrase queer-feminist punk because it seems more appropriate for addressing the lexibility and openness of the terms

of self-identiication and the research ield, as well as the countercultural productions and spaces it covers. In addition, I choose to

label queer-feminist punk as a political movement to further account for the lexibility and diversity of identiications, politics, artistic expressions and productions, and the social structures within

them. Moreover, it accounts for the processes of countercultural

knowledge production and transmission that have taken place

31

�over the last three decades. Although the social bond between

the collected individuals, communities and their art is fragmented, and to some degree inconsistent, feelings of belonging to the

broader queer-feminist punk movement are important for its protagonists, as will be shown. Besides the identiication with queer

and feminist politics, this sense of belonging is expressed through

references to punk music and politics. It ought to be emphasized

that the subsumption of the diverse crowd of people, identities,

and cultural productions provided here, although eclectic to some

degree, is appropriate not least because of the shared anti-social

queer-feminist politics. These politics are found on the verbal or

language-based level, as well as on the level of embodiment, musical style and sound. Punk music and sound must be understood

as a politics of negativity as such.

I will explain why queer feminists appropriated the music, style

and political concept of punk rock for their political activism, rereading some early queer-feminist punk articles. Furthermore, I

will focus on some of queer-feminist punks’ main agendas and

points of critique at that time in history. Second, I will explain

queer-feminist punk aesthetics and politics, by making a brief digression to the origins of punk rock in the 1970s, more precisely

to the emergence of punk as an anti-social aesthetic form. Moreover, I will trace the speciic forms of expressions of negativity

occurring in queer-feminist punk back to punk concepts, while

relating them to queer concepts and movements. In doing so, I attempt to add queer-feminist punk rock to the archive of scholarly

anti-social queer theory as well as queer counterculture productions. Third, I will show that the anti-social queer theory of queerfeminist punk is characterized by an intersectional approach. In

other words, queer-feminist punks target not only homophobia,

transphobia and misogyny, but also understand the intersectionality of oppressive power structures across the categories of race,

class, and able-bodiedness.

The notion of an archive that I want to promote here necessarily—as Judith Jack Halberstam has stated—

32

�extend[s] beyond the image of a place to collect material or hold documents, and [...] has to become a loating signiier for the kinds of lives implied by the paper

remnants of shows, clubs, events, and meetings. The

archive is not simply a repository; it is also a theory of

cultural relevance, a construction of collective memory,

and a complex record of queer activity. (In a Queer Time

and Place 169)

I see my work as a contribution to such a queer theory archive,

while acknowledging and emphasizing the problematic position

that it occupies, especially within the countercultural spheres

of queer-feminist punk. It is problematic because my presentation and analysis of people, bands, and events relect my white

European academic background, education and personal interests. Moreover, by claiming space within academic queer theory for queer-feminist punk, the politics and cultural productions

become incorporated in academic discourses, regardless of how

marginal those discourses might be within academia. In relation

to the critique on the incorporation of countercultural knowledge

and art into academia, the inal part of this chapter discusses and

further problematizes the subjectivity of documenting and archiving the queer-feminist punk movement. This is done in order

to highlight accessibility as one major aspect of the queer-feminist punk agenda.

33

�2.1. “Gay Punk Comes Out with a Vengeance”:31

The Provisional Location of an Origin

The irst documented use of the name homocore (which later became replaced by queercore) was in the Toronto-based zine J.D.s,32

created by the ilmmakers, artists, and musicians G.B. Jones and

Bruce LaBruce in 1985/6. “Homocore [a neologism created out of

the terms homosexuality and hardcore] was the name of this ictitious movement of gay punks that we created to make ourselves

seem more exciting than we actually were,” says Bruce LaBruce

(qtd. in Ciminelli and Knox 7). “Queercore was a call to arms and

storming out of the closet,” Adam Rathe notes in his oral history of queercore Queer to the Core. The zine J.D.s featured photos,

drawings and comics about queers within punk scenes in Canada

and the US mixed with personal stories by queer punks, mockeries of Hollywood stars and articles on homophobia and sexism.

The politics of J.D.s were communicated through various forms of

writings, graphic designs and drawings. During its existence, J.D.s

developed an increasingly ierce criticism of mainstream culture

and politics, as well as of the gay and hardcore scenes. Issue 5

from 1989, for example, included a collection of angry fan letters

by gays and lesbians to Maximumrocknroll,33 as well as a collection

of writings that exposed homophobic messages from the same

magazine. J.D.s, like the many publications that followed, was

31 Rathe, Adam. “Queer to the Core: Gay Punk Comes Out with a Vengeance.

An Oral History of the Movement That Changed the World (Whether You

Knew It or Not).” Out. Web. 12 April 2012. <http://www.out.com/> (capitalization added).

32 Bruce LaBruce mentions that the primary meaning of J.D.s was “Juvenile

Delinquents,” but adds that “[i]t also stood for James Dean and J. D. Salinger. And [...] Jack Daniels” (qtd. in Rathe 2).

33 Maximumrocknroll is a very popular, widely distributed, monthly fanzine from San Francisco founded in 1982, which covers bands and news

from punk scenes all over the world. Its production and distribution are

very professional, and also allow for international mail orders. While the

magazine itself is done in an early punk style, it is professionally printed

and digitally edited, produced on thin newsprint paper, uses many different fonts and has no page numbers.

34

�created as a twofold intervention to queer the macho-dominated punk rock scenes by contributing to them from a queer-feminist perspective, as well as deliver a harsh critique of gay lifestyle

cultures through punk style and politics. Every issue also included a list of punk bands and titles, which helped queers to learn

about and connect with each other. LaBruce also produced a homocore compilation tape, for which he recruited people through

J.D.s.34 Although it might be an overstatement to call LaBruce and

Jones the founding igures of queer-feminist punk, they certainly

played a signiicant role within the movement.35 Jones, LaBruce

and their activism reached the broader punk scenes all over the

US and beyond with an angry six-page article in an issue of Maximumrocknroll titled “Don’t Be Gay: Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Fuck Punk up the Ass” in 1989. The piece criticizes the

gay and punk scenes, as well as mainstream culture in extremely

blunt and sometimes very ofensive language.

Soon after the introduction of the term homocore in J.D.s in

1985, the San Francisco-based queer punks Tom Jennings and

Deke Motif Nihilson, who played in the queercore band Comrades

In Arms, took up the label for their own zine. Jennings and Nihilson

met at Toronto’s Anarchist Survival Gathering in 1988, where they

were exposed to Jones’ and LaBruce’s zines and politics (Ciminelli

and Knox 9). Homocore’s irst issue emerged in the same year as the

typical Xerox-printed zine style. Until its inal issue in 1991—even

as the aesthetics of Homocore became more professional—the

zine was printed in newspaper style and format. Its politics also

remained DIY, featuring punks and punk productions from all

over the world, from various punk groups to artists and writers

like LaBruce, Jones, Steve Abbott and Daniel Nicoletta, Chainsaw

34 See Jones and LaBruce, J.D.s 5.

35 By 1989, Jones and LaBruce had already connected a quite impressive

number of queer-feminist punk bands and zines, the latter including

Los Angeles-based Homocore from San Francisco, Notes From The Floorboards from Warren, Ohio, and Raging Hormones (anarchist-lesbian zine)

from Boulder, Colorado (see Jones and LaBruce, J.D.s 5 47–8). Explicit

references to J.D.s as inspiration to create a zine can also be found in the

San Francisco-based Fucktooth (Screams 35), and Outpunk (1).

35

�Records label owner and musician Donna Dresch, and Lookout Records founder Larry Livermore. Homocore zine not only covered

and inluenced an impressive number of Bay Area and West Coast

queer-feminist punks but also connected bands and zine writers

from far-lung places and beyond national borders, as local zines

like Homocore NYC (Flanagin, Girl-Love) document.

Around 1988, a queer-feminist punk scene emerged in New

York around the “Lower East Side Mecca The World, where the Sissiied Sex Pistol threw Rock 'n' Roll Fag Bar on Tuesday” (Downey

24). New York locals Sharon Topper and Craig Flanagin formed

their band God Is My Co-Pilot36 in 1990. The two editors of the zine

Homocore NYC were well connected with queer-feminist punks all

over the US and their band project was frequently supported by a

varying set of other New York-based musicians such as Fly, Daria

Klotz, John Zorn, Jad Fair, Fredrik Haake and others.37 Moreover,

they inluenced generations of queer-feminist punks such as the

Skinjobs, whose name picks up a theme from God Is My Co-Pilot’s

song Replicant. An early Los Angeles-based queer-feminist punk

was drag performer Vaginal Crème Davis. Davis, who refers to herself as “an originator of the homo-core punk movement and a gender-queer art-music icon” on her personal website, made a name

for herself with her DIY zine Fertile La Toyah Jackson Magazine,38 before she entered more deeply into punk music and history with the

zine Yes, Ms. Davis and her various band projects. Starting her music career with the Afro Sisters around 1978, Davis has performed

36 God Is My Co-Pilot was probably named after the 1945 American propaganda ilm based on the autobiography of Robert Lee Scott, Jr., a United

States Army Air Force pilot during World War II.

37 Their lyrics almost exclusively addressed themes of sexuality and gender, most of them in English with occasional lines in French, Yiddish,

German, Finnish, and Turkish, among others. Their creative work between 1991 and 1999 encompasses more than 15 full-length albums,

many singles, a compilation and several zines.

38 Vaginal Crème Davis’ punk zine Fertile La Toyah Jackson Magazine

(1982–1991) actually predated Jones’ and LaBruce’s zine by a couple of

years. Drag performer Davis produced various zines during her long and

ongoing career, including Dowager (1972–1975), Crude (1976–1980),

Shrimp (1993) and Yes, Ms. Davis (1994), as well as Sucker (1995–1997).

36

�with Cholita! The Female Menudo (where she played with punk

legend Alicia Armendariz aka Alice Bag) from the 1980s on, as well

as with the more recent Black Fag, who shares its name with another queer-feminist band from the Bay Area. The band that scholars have paid most attention to regarding the topic of queercore

is Pedro, Muriel and Esther.39 A more detailed discussion of Pedro,

Muriel and Esther, its particular use of negative queer punk aesthetic and content with a focus on Vaginal Crème Davis is provided in chapter three. In the band Pedro, Muriel and Esther, Davis

performed with Glen Meadmore, another of Los Angeles’ provocative music and drag performance artists. Country punk Meadmore

garnered media attention for his outrageous stage performances,

which included getting naked and “stick[ing] a chicken head up

his butt” (Ciminelli and Knox 77).

Around the same time that Meadmore and Davis appeared

on punk stages, another ierce and furious punk band featuring queer themes entered Los Angeles’ punk scene: Extra Fancy.

Neither Extra Fancy’s singer, Brian Grillo, who was the only gay

member of the band, nor his bandmates identiied with the label

queercore (Ciminelli and Knox 19). Nevertheless, their music inluenced many queercore musicians with their “particular variant

of the hardcore” (Schwandt 77) style. Grillo was well-connected

with queer-feminist punks like Ryan Revenge from the band Best

Revenge and the independent label Spitshine Records, and the

band’s concerts attracted a committed queer-feminist fan community (Ciminelli and Knox 18–42). Furthermore, Extra Fancy’s

lyrics “explicitly and often graphically address male homosexuality,” as musicologist Kevin Schwandt observed (77). Such lyrics intervened in the homophobic punk culture of Los Angeles

and beyond. Interestingly, Extra Fancy continued to be a strong

inluence within the hardcore community despite their explicitly queer lyrics. They managed to do this through “[t]he exaggerated masculinity of Brian Grillo’s performing image” (ibid. 89).

Schwandt analyzed Grillo’s performances of masculinity as

39

See Muñoz, Disidentiications 93–115.

37

�a unique sort of empowerment dependent upon the

musical expression of a rough gay male sexuality. The

musical deployment of this macho sexual self-fashioning [...] conlates a conception of contemporary masculinity often discursively denied to gay men with an

idealized sexual past in which queer machismo is perceived as having been self-consciously fostered. Grillo’s

sexuality becomes the musical source of a threatening,

violent potential for resistance to homophobia. (ibid.)

Grillo’s performances were successful interventions in hardcore

scenes, where more ambiguous masculinities or femininities simply had no access. Moreover, Grillo ofered an alternative form of

queer and punk masculinity that was rarely represented in the

gay lifestyle culture of that time. Nevertheless, his representation

of masculinity also conirmed mainstream body images and gender roles.

One of the few queercore bands to reach audiences the size

of football crowds were Pansy Division. According to his autobiography Delowered (18), Pansy Division’s initiator Jon Ginoli was

inspired to form a pop-punk bank by the San Francisco zine Homocore and by J.D.s. Ginoli and Chris Freeman started Pansy Division in 1991,40 and continued for 16 years until inally disbanding in 2007. Interestingly, Ginoli explicitly refers to his music as

a form of queer activism in Delowered (27). He had been looking for a form of activism that appealed to him during the late

1980s and early 1990s and had been part of ACT UP in San Francisco, but had become alienated from the movement by 1990.

“[F]orming Pansy Division was [his] way of doing activism” (ibid.).

In 1994, Pansy Division reached mainstream publicity when they

toured with Green Day.41 Pansy Division’s music, though clearly

40 In 1996 drummer Luis Illades joined the band, followed by guitarist Joel

Reader in 2004.

41 Green Day is a contemporary punk band from Berkeley, CA. They

emerged from the Bay Area’s radical political grassroots punk scenes

and became world famous in 1994. Green Day’s major label debut

38

�emphasizing fun over punk rage and anger, always had a political

and educational purpose. Their lyrics featured queer themes and

they used their concerts and record releases to provide queer

communities with important information. On their album Delowered, for example, they released a list of contact addresses of

gay youth groups around the US. Pansy Division went on multiple tours throughout the US, Canada and many places in Europe. They were well-connected with other queer-feminist bands

like Tribe 8, and riot grrrl icons Bikini Kill. Ginoli describes his life

with Pansy Division, the numerous tours, friendships and alliances with other queer-feminist punks, their connections to punk

scenes in general, the diferent places they played, as well as the

reactions of audiences and the press in his book Delowered. His

autobiographical book, written in the style of a diary, is a very

important contribution to what Judith Jack Halberstam refers to

as a queer archive (In a Queer 32–33). It exempliies how aesthetics, sound, pleasure and politics are interwoven within queercore.

Furthermore, it can be read as a documentation of the impact

that this music with political content had on its protagonists, fans

and sometimes opponents.

Equally important for the fast propagation of queer-feminist

punk was the previously mentioned San Francisco-based Tribe 8.

I will analyze Tribe 8’s aesthetic and politics with a special focus on

feminism in chapter ive in detail. However, I irst want to emphasize Tribe 8’s key role within the queer-feminist punk movement.

Founded in 1991, “San Francisco’s own all-dyke, all-out, in-yourface, blade-brandishing, gang castrating, dildo swingin’, bullshitdetecting, aurally pornographic, neanderthal-pervert band of patriarchy-smashing snatchlickers” (Breedlove qtd. in Wiese) caught

an impressive amount of attention from fans, other musicians and

many scholars from all over the world. In particular, singer Lynn

album Dookie sold over 10 million copies in the US alone. Their songs

“American Idiot” and “Boulevard of Broken Dreams,” released in 2005

have each been downloaded more than 100,000 times according to the

Recording Industry Association of America (Web. 9 May 2012. <http://

www.riaa.com/>).

39

�Breedlove42 and guitarist Leslie Mah, the only constant members

of the band (which disbanded around 2005), were important igures in various queer-feminist scenes and punk movements. Mah

began her punk career around 1984 with the band ASF (Anti-Scrutiny Faction) in Boulder, Colorado (Al Flipside), before she moved

to San Francisco. Mah’s strong connections to the queer-feminist

punk movement can be seen in G.B. Jones’ ilm The Yo-Yo Gang,

where she and ASF member Tracie Thomas participated side by

side with other early queercore musicians like Bruce LaBruce,

Donna Dresch, and Deke Nihilson. Mah was not only a founding

igure of queercore, but also one of the scene’s important critics. She pointed to the whiteness of queer-feminist punk circles,

where self-identiied Asian-Americans—like Mah herself—were

severely underrepresented. Together with her New York-based

friends Margarita Alcantara-Tan, editor of the long-standing zine

Bamboo Girl, and fellow queer-feminist punk musician Selena

Wahng, she thematized the issues of race blindness and racism

within queer-feminist scenes (Alcantara, Mah, and Wahng). In addition, Mah served as a role model for other bisexual and feminine punks within the general climate of rejecting femininity as

well as heterosexuality.

One point of political consensus among all of these very diverse cultural products, as well as the broader queer punk rock

scene, was a disagreement with assimilatory gay and lesbian politics, as well as the all too often lifestyle-oriented gay and lesbian

subcultures. “Gay culture had gotten very boring and bourgeois,

so they needed an alternative,” as Bruce LaBruce (qtd. in Thibault)

put it. In an interview for the gay magazine Oasis, Bruce LaBruce

42 Lynn Breedlove continued her/m queer-feminist punk politics in her/m

books and the stand-up comedy show One Freak Show: Less Rock, More

Hilarity. S/he also hosted Kvetch, a queer open mic night, and a radio

show called Unka Lynnee Show, “a two hour cavalcade of queer hits

throughout the ages, liberally sprinkled with Breedlove’s comic feminist

and trans theory” (Breedlove), on the community radio PirateCatRadio

in San Francisco. In 2003, s/he organized The Old Skool New Skool Project, “monthly events teaming irst and second generation women’s music stars” (Breedlove).

40

�recalls why many young people could relate to punk politics in

the late 1980s:

It was a very active and political movement [...] very

much based on style [...]. It was a way for kids to express

their diference in more ways than just the sexual act.

[...] Punk came from a very gay-identiied place to begin with (punk was the prison slang for a passive homosexual, and then later became associated with juvenile

delinquents), and the early days of punk in the seventies

were very much about sexual revolution and diference.

(LaBruce qtd. in Thibault)

As LaBruce mentions in this quote, one important feature of punk

rock for queer feminists was its style, especially punk’s rhetoric.

Punks used a particularly extreme language to reject the existing sociopolitical systems and culture surrounding and supporting them. The lyrics from Destroy’s43 song Burn This Racist System