6

International Studies in Education 9 (2008)

Divergent Trends in Higher Education

in the Post-Socialist Transition

Cathryn Magnoa,* and Iveta Silovab

a

Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies Southern Connecticut State University

b

College of Education, Lehigh University

Democratic and economic ideals have driven many

initiatives in the post-Soviet transition. A review of

gender equity as measured by higher education participation reveals divergent trends in the region. Initial

expectations that democratization through policy and

participation would be associated with increased or

continuing gender equity in the region have come to

fruition in some but not all countries. An economic

incentive of achieving high rates of enrollment in higher

education institutions is increased employability of the

potential work force to serve a growing economy. Two

concurrent economic goals of the transition economies

of Central and Southeastern Europe, Baltics, Western

Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) and Central Asia have been to increase the standard of living

(Newell & Reilly 1999) and transform toward market

economies (Svejnar 2002), however work force needs

and preferences have diversified in the new economies.

Employment opportunities have broadened during the

transition, however some young people are vulnerable

to new insecurities and inequalities. There is evidence

that young women, in particular, are being left out of

the job market (UNICEF TransMONEE 2007a). Higher

education participation reflects these changing contextual influences.

This article highlights two divergent trends related

to gender dynamics in higher education. The first trend

reveals the increase in the number of female students in

higher education in most countries of the region, especially in the countries of Southeastern/Central Europe

and the Baltics. The second trend, however, documents

major setbacks in terms of gender equality

____________________

*Corresponding author: Email: magnoc1@southernct.edu;

Office: +1.203.392.5170; Address: 501 Crescent Street,

New Haven, CT 06515, USA.

"

in some countries of Central Asia, where female

enrollment in higher education has been decreasing

throughout the transition period. A careful examination

of these two trends, based on previous investigation and

recent data review, reveals interesting gender dynamics

during the post-socialist transition period and suggests

that more research into the causes and consequences of

gender inequalities in higher education is needed.

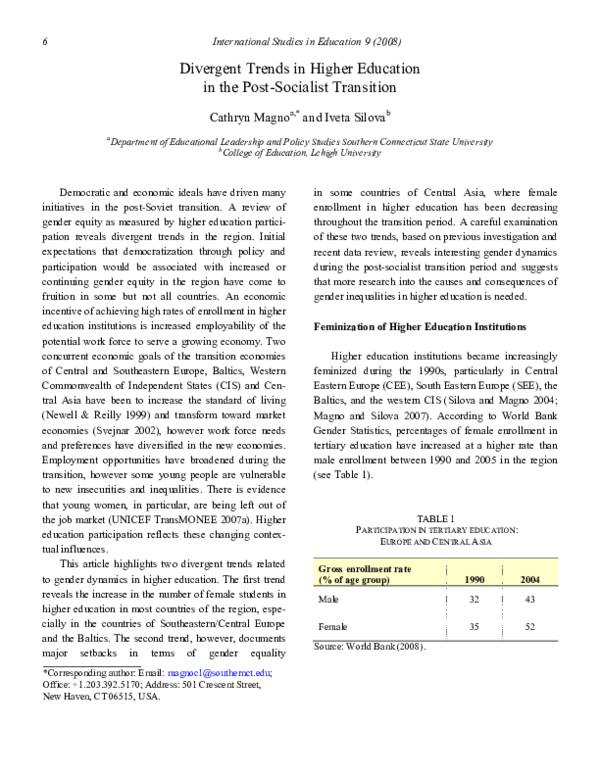

Feminization of Higher Education Institutions

Higher education institutions became increasingly

feminized during the 1990s, particularly in Central

Eastern Europe (CEE), South Eastern Europe (SEE), the

Baltics, and the western CIS (Silova and Magno 2004;

Magno and Silova 2007). According to World Bank

Gender Statistics, percentages of female enrollment in

tertiary education have increased at a higher rate than

male enrollment between 1990 and 2005 in the region

(see Table 1).

TABLE 1

PARTICIPATION IN TERTIARY EDUCATION:

EUROPE AND CENTRAL ASIA

Gross enrollment rate

(% of age group)

1990

2004

Male

32

43

Female

35

52

Source: World Bank (2008).

�International Studies in Education 9 (2008)

7

TABLE 2

PERCENTAGE OF FEMALE STUDENTS IN HIGHER EDUCATION, 1990–2005

Country by Region

Czech Republic

Hungary

Poland

Slovakia

Slovenia

1990

38.4

48.6

50.2

46.9

55.6

1995

38.3

0.0

56.0

47.3

56.4

2000

36.9

54.7

56.8

50.8

56.1

2005

51.9

58.2

56.5

58.3

58.5

Estonia

Latvia

Lithuania

49.3

54.5

55.8

52.0

57.4

59.7

60.1

61.8

59.9

61.6

-

Bulgaria

Romania

48.7

47.2

60.7

50.3

56.1

53.5

53.5

55.4

Albania

Bosnia-Herzegovina

Croatia

FYR Macedonia

Serbia and Montenegro

51.3

51.0

50.8

48.9

48.3

53.8

53.6

54.0

54.8

63.2

52.8

54.5

55.8

55.7

58.4

54.1

56.7

-

Belarus

Moldova

Russia

Ukraine

52.3

0.0

50.5

50.3

52.7

54.7

54.3

49.9

56.4

56.3

56.7

52.6

58.2

57.9

58.2

54.6

Armenia

Azerbaijan

Georgia

45.9

37.9

45.4

51.1

43.8

52.5

54.9

41.7

48.9

54.8

47.7

-

Kazakhstan

60.2

Kyrgyzstan

51.2

Tajikistan

36.6

Turkmenistan

41.4

Uzbekistan

41.0

Source: UNICEF TransMONEE (2007).

66.6

50.8

26.9

36.4

38.9

54.3

50.9

23.7

31.9

37.8

57.9

55.6

26.8

40.9

For example, in countries in transition, there are

nearly 130 women enrolled in higher education for

every 100 men (UNESCO 2008). Female students constituted over 55 percent of all higher education students

in Central/Eastern Europe (Hungary, Poland, Slovakia,

Slovenia, and Romania), Southeastern Europe (Albania,

Former Yugoslav Republic (FYR) of Macedonia), as

well as the former Soviet Union (Belarus, Moldova,

Russia, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan). In the three Bal"

tic States (Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania), female students constituted over 60 percent of all higher education

students (see Table 2).

The reasons behind this phenomenon are difficult to

trace, especially because research on the gendered aspects of the school environment is still lacking.1 One

explanation could rest on the high employability of

young men in more capitalist economies. As a result of

new opportunities (also related to the expansion of the

�8

International Studies in Education 9 (2008)

European Union), men are often choosing to enter the

workforce rather than enroll in higher education. In fact,

evidence that men are leaving to find work outside of

the region is supported by high rates of remittances for

some countries, especially the poorest (remittances

represent 20 percent of GDP in Moldova and Bosnia

and Herzegovina, 10 percent of GDP in Albania, Armenia, and Tajikistan, and up to 5 percent of GDP in other

Balkan states and the Baltics) (World Bank 2007). Conversely, women may be less mobile and finding fewer

employment opportunities and are therefore pursuing

higher education at higher rates (see Table 3).

TABLE 3

UNEMPLOYMENT BY LEVEL OF EDUCATION:

EUROPE AND CENTRAL ASIA

Tertiary Education Level

2000

% of male unemployment

23

% of female unemployment

34

Source: World Bank (2008).

There exist several other potential explanations.

First, male students may prefer to study in evening

schools or vocational/technical institutions instead of

universities in order to simultaneously participate in the

labor market. Second, female students may make more

effort to enter higher education institutions. For example, a Hungarian study revealed that significantly more

female students participated in academic contests during their secondary school years, had better grades, and

acquired more cultural capital than male students.2

Third, women in Eastern/Central Europe appear to have

greater support mechanisms to continue studies in higher education. Compared to socialist period, preschool

enrollments increased in eight out of nine countries in

Eastern/Central Europe, while the substantially decreased in the Caucasus and Central Asia. In Latvia, for

example, preschool enrollments rose from 53.9 percent

in 1989 to 80.1 percent in 2005 (UNICEF TransMONEE 2007b). The situation is similar in other countries

"

(Czech Republic, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia, Bulgaria,

and Romania) where preschool enrollments constitute

over 70 percent, compared to an average of 18 percent

(UNICEF TransMONEE 2007b). It is likely that greater

childcare opportunities have played a role in more active female participation in higher education institutions.

However, it is important to look beyond the statistical data pointing to the feminization of higher education in Eastern/Central Europe in order to examine

whether and why gender inequities exist in employment. Gender gaps in employment opportunities and in

salaries show women earning an average of 25 percent

less than men in South, Central and Eastern Europe

(Open Society Institute 2006), which may account for

women choosing higher education over labor market

participation. In addition, higher education study continues to be segregated by gender. For example,

throughout Eastern/Central Europe, women are more

likely to choose fields such as humanities and arts, education and medicine (including nursing), while men are

more likely to choose to study engineering, mathematics, natural sciences and computing (United Nations

Economic Commission for Europe 2006).

Disadvantage for Female Students in Central Asia

and the Caucasus

Partly in reaction to allegedly egalitarian gender politics

of the socialist regime, a new patriarchal ideology has

emerged, forming new national identity discourses and

naturalizing the dominant male norm in the region (Olson et al. 2007). In some countries of Central Asia and

the Caucasus, in particular, attitudes regarding women’s

roles in society grew more conservative during the transition period. For women, this means a reassertion of a

more traditional role of caring for the family and rearing

children, which undoubtedly affects girls’ educational

opportunities. In Uzbekistan, for example, more than 25

percent of girls do not continue education after they

reach working age. Of all higher education students

there, women constitute only 37.8 percent.3 In Tajikistan, women constitute approximately 25 percent of all

students, uncovering a growing differential between

�International Studies in Education 9 (2008)

young men and women. Overall, the education level of

many women in these countries is strongly influenced

by their reproductive load (the largest numbers of children are born to women in their 20s) and the re-emerging

traditional patriarchal values. In addition, neo-liberal

reforms have compromised the rights of many women.

As a result, some women have been forced to participate in the newly expansive sex market. Many students

have bribed their teachers or engaged in prostitution to

earn enough money to attend universities.4

In addition to the resurgence of patriarchal cultural

and traditional values, structural, systemic changes such

as the dramatic reduction of universal preschool has

overburdened women (see Table 4).

9

In societies where women used to be employable due to

child care provision through preschool, women in some

countries of the former socialist bloc are now faced with

the primary child care responsibilities, forfeiting higher

education and career paths to raise children. Another

example of structural change is in the policy arena

where, in Tajikistan for example, the compulsory education level was lowered to grade nine, and as a result

girls left upper secondary school in large numbers

(Magno, Silova and Wright 2004).

A final potential explanation for lower enrollment

of women in some regions could be the overall low

levels of spending on education, especially for countries

in the Caucasus and Central Asia. Tajikistan spent less

TABLE 4

PRE-PRIMARY ENROLLMENT NET RATES, PERCENT OF POPULATION AGED 3-6:

CAUCASUS AND CENTRAL ASIA

Country

1989

Armenia

48.5

Azerbaijan

25.1

Georgia

44.6

Kazakhstan

53.1

Kyrgyzstan

31.3

Tajikistan

16.0

Turkmenistan

33.5

Uzbekistan

38.8

Source: UNICEFTransmonee (2007b).

per capita on education than most other countries in the

world in 2001, and Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, and Moldova

spending was lower than in countries with similar or

lower levels of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per

capita (UNICEF Innocenti Social Monitor 2006). The

lack of education spending by governments means that

households must make greater payments, which in turn

penalizes poor households and reinforces gender and

other inequalities (UNICEF Innocenti Social Monitor

2006).

Conclusion

Youth in the typical higher education age bracket

have spent all or part of their early lives during the most

"

1998

2005

23.8

12.9

25.8

12.5

8.7

6.0

19.2

17.9

31.8

20.9

18.4

11.1

6.9

21.3

turbulent years of the transition period. Unclear and

evolving economies and the restructuring of the labor

market over the past fifteen years translate into the current demand for more complex job skills. Gender dynamics, along with cultural, social and political factors

in each country/region context influence women’s and

men’s decisions to enroll in higher education, and more

specifically their decisions regarding fields of study.

The ability of the transition governments to support

tertiary education in connection to future labor market

needs and structures will be critical to monitor and examine over the coming years. Questions that merit further investigation include: how structural and systemic

changes in the lower educational levels affect tertiary

enrollments; how gender and other factors such as pov-

�10

International Studies in Education 9 (2008)

erty intersect in decision-making regarding higher education; how country-specific political and economic

policies affect male and female higher education enrollment; and how economic sector planning might

affect job opportunities in urban and rural areas.

References

Magno, Cathryn, and Iveta Silova. 2007. Teaching in

Transition: Examining School-based Gender Inequities in the Post-Socialist Region. Journal of International Educational Development 27 (6): 647–660.

Magno, Cathryn, Iveta Silova, and Susan Wright. 2004.

Open minds. New York: Open Society Institute.

Newell, Andrew, and Barry Reilly. 1999. Rates of Return to Educational Qualifications in the Transitional Economies. Education Economics 1 (1): 67–84.

Olson, Josephine E., et. al. 2007. Beliefs in Equality for

Women and Men as Related to Economic Factors in

Central and Eastern Europe and the United States.

Sex Roles 56 (1): 297–308.

Open Society Institute. 2006. On the Road to the EU:

Monitoring Equal Opportunities for Women and

Men in Southeastern Europe. Budapest and New

York: Network Women’s Program.

Silova, Iveta, and Cathryn Magno. 2004. Gender Equity

Uunmasked: Revisiting Democracy, Gender and

Education in Post-Socialist Central/Southeastern

Europe and the Former Soviet Union. Comparative

Education Review 48 (4): 417–442.

Svejnar, Jan. 2002. Transition Economies: Performance

and Challenge. Journal of Economic Perspectives

16 (1): 3–28.

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe.

2006. Equal Access to the Same Fields of Study.

New York: United Nations Economic Commission

for Europe. Available online at:

http://www.unece.org/gender/genpols/keyinds/educ

ation/eqaccess2.htm.

UNESCO. 2008. Gender Parity: Not There Yet. Paris:

UNESCO Institute for Statistics.

"

UNICEF Innocenti Social Monitor. 2006. Understanding Child Poverty in South-Eastern Europe and the

Commonwealth of Independent States. Florence:

UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre.

UNICEF TransMONEE. 2007a. Features. Florence:

UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre.

UNICEF TransMONEE. 2007b. Database. Florence:

UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre. Available online at: http://www.unicefirc.org/databases/transmonee/2007/Tables_TransM

ONEE.xls.

World Bank, The. 2007. Migration and Remittances:

Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union.

Washington, DC: The World Bank.

World Bank, The. 2008. World Bank Gender Stats.

Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Notes

1

Gender analysis is only one approach to understanding

shifting enrolments. Certainly context-specific variables

such as culture, conflict, and availability of higher education institutions all contribute to a full explanation.

2

The study was conducted by the Youth Research

Group of the Institute of Educational Research among

first year university students of economics and law. The

research was coordinated by Kálmán Gábor and conducted in the 1998 1999 academic year.

3

Ministry of Macroeconomics and Statistics and State

Department of Statistics, Women and Men of Uzbekistan: Statistical Volume, 2002.

4

For a more detailed explanation of the relation between

prostitution and higher education in Kazakhstan see

chapters three and five in Joma Nazpary, Post-Soviet

Chaos: Violence and Dispossession in Kazakhstan

(London, United Kingdom: Pluto Press, 2002; see also

Jakob Rigi, “Conditions of post-Soviet Youth and Work

in Almaty, Kazakhstan,” Critique of Anthropology 23,

no. 1 (2003), p 35-49.

�

Cathryn Magno

Cathryn Magno Iveta Silova

Iveta Silova