GÁBOR ILON

THE GOLDEN TREASURE FROM

SZENT VID IN VELEM

The Costume of a High-Ranking Lady of the

Late Bronze Age in the Light of New Studies

789639911697

9 789639911710

��ARCHAEOLINGUA

Edited by

ERZSÉBET JEREM and WOLFGANG MEID

Series Minor

36

�Commemorating

The 155th anniversary of the birth of Kálmán Miske (b. 1860)

who discovered the golden treasure

The 105th anniversary of the birth of Amália Mozsolics (b. 1910)

who published the first monograph on the golden treasure

The 76th anniversary of the birth of Gábor Bándi (b. 1939)

who directed the archaeological investigations

exploring the largest area of the archaeological site

�GÁBOR ILON

The Golden Treasure from

Szent Vid in Velem

The Costume of a High-Ranking Lady of the

Late Bronze Age in the Light of New Studies

BUDAPEST 2015

�The publication of this volume was generously funded by

the National Cultural Fund of Hungary,

the Savaria Museum and the Pannon Kulturális Örökség Egyesület

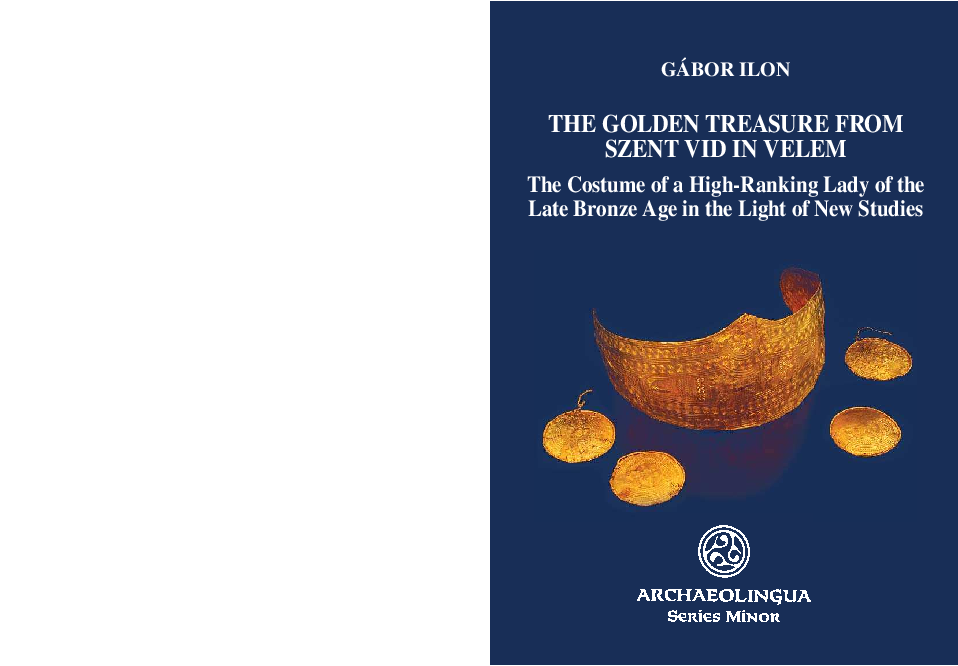

Front Cover

The diadem and the domed roundels of the golden treasure

(photo by Tamás Tárczy)

Back Cover

St. Vid Hill of Velem (photo by the author)

ISBN 978-963-9911-71-0

HU-ISSN 1216-6847

© Gábor Ilon and Archaeolingua Foundation

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system,

or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, digitised, photocopying,

recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher.

2015

ARCHAEOLINGUA ALAPÍTVÁNY

H-1250 Budapest, Úri u. 49

Desktop editing and layout by Rita Kovács

Printed in Hungary by Prime Rate Kft

�Table of Contents

Prologue ............................................................................................................. 7

1 Introduction: the findspot, the find circumstances

and the history of research of the golden treasure .......................................... 9

1.1 Kálmán Miske and the archaeological site .............................................. 9

1.2 Kálmán Miske and the discovery of the golden treasure ....................... 15

1.3 Investigating the golden treasure:

Amália Mozsolics and Gábor Bándi ...................................................... 22

2 Description of the artefacts and the results of the new conservation project 25

2.1 Description of the artefacts based on Kálmán Miske’s incomplete

manuscript, our observations and the results of the conservation ......... 25

2.1.1 The diadem .................................................................................. 26

2.1.2 The domed roundels .................................................................... 27

2.1.3 The bronze backplates ................................................................. 29

2.1.4 The gold spirals ........................................................................... 29

2.1.5 The weight of the treasure ........................................................... 30

2.2 Extract from Katalin T. Bruder’s conservation diary ............................. 31

2.2.1 The first phase of the conservation project:

assessment of the condition of the artefacts ................................ 31

2.2.2 The second phase of the conservation project:

the reconstruction of the artefacts ............................................... 35

2.2.3 Summary of the results of the conservation project .................... 35

3 The results of the archaeometric analysis of the golden treasure ................. 39

3.1 The results of the scanning electron microscopy

with X-ray microanalysis (SEM-EMA) and their evaluation ................ 39

3.2 Metal provenance studies in a European context ................................... 43

4 The ornament of the jewellery and the craftsmanship of the diadem ........... 47

4.1 Decorative motifs and the goldsmith’s tools used for their creation ..... 47

�6

4.1.1 Domed roundels, Pair I ................................................................ 47

4.1.2 Domed roundels, Pair II ............................................................... 48

4.2 Prehistoric weights and value standards in western Hungary ................ 59

4.3 Goldsmithing (blacksmithing) tools from Vas County

in relation to the golden treasure and the manufacturing of the foils .... 65

4.4 The symbolism of the golden artefacts unearthed in Velem .................. 69

5 Diadem types, how they were worn, and social gender in prehistory .......... 75

6 Analogies of the gold domed roundels of the Velem type ............................ 87

7 Analogies of the gold spiral tangle:

the assumed breast ornament (pectoral) ........................................................ 93

8 Reconstructions of the how jewellery of the golden treasure was worn ....... 99

9 The dating of the golden treasure in the light of radiocarbon data from

northwestern Transdanubia ......................................................................... 107

10 The deposition of the golden treasure ........................................................ 113

11 Conclusion ................................................................................................. 117

12 Epilogue .................................................................................................... 121

13 Acknowledgements ................................................................................... 123

Abbreviations ................................................................................................. 125

References ...................................................................................................... 125

Appendix ........................................................................................................ 173

List of Figures ................................................................................................ 179

Figures ............................................................................................................ 195

�Prologue

The golden treasure was discovered in the last days of August in 1929, in the

course of an archaeological excavation conducted by Baron Kálmán Miske. The

first monograph on this remarkable assemblage, written by Amália Mozsolics, was

published twenty-one years later; Gábor Bándi’s study, focusing specifically on

the diadem of treasure, appeared after a period of thirty-seven years. Yet another

thirty-two years elapsed before the present author completed his manuscript. My

attention was directed to this golden treasure by Dr. Ottó Trogmayer, who in

1999 organised an exhibition in the Helikon (Festetics) Palace Museum of the

most fascinating artefacts kept in various museums of Budapest and of the county

seats. This exhibition was accompanied by a bilingual catalogue.∗ Dr. Trogmayer

requested the gold diadem for the exhibition. Before loaning it, I held it in my

hands for the very first time and I was horrified to see its terrible condition, as

was Dr. Trogmayer. Therefore, after the exhibition and as soon as I was able to,

I announced a tender (2003), and as a result, the conservation of the diadem was

carried out between 2004 and 2006. At the same time, I believed that I would be

able to answer at least some of the questions that had bedevilled archaeological

scholarship for so long about this dazzling assemblage. This work lasted for many

years: the present volume is a reflection of what I have accomplished as well as a

reminder that our work on this spectacular treasure remains unfinished as it was

for my predecessors; it shows the options I had at my disposal, and what I have

been actually able to achieve.

K szeg, August 20, 2014

Gábor Ilon

*

László Czoma (ed.): Ritkaságok, becses óságok. Magyarország megyéinek és

f városának muzeális kincsei a keszthelyi Festetics-kastélyban 1999–2000. – Raritäten,

kostbare Altertümer. Museale Schätze der ungarischen Komitate und der Hauptstadt

im Festetics-Schloß in Keszthely 1999–2000. Keszthely, Helikon (Festesics) Palace

Museum, 1999.

��1 Introduction: the findspot, the find circumstances and

the history of research of the golden treasure

1.1 Kálmán Miske and the archaeological site

Located on the eastern spur of the Alps, the area of St. Vid Hill in Velem was

investigated in detail during a topographical survey performed during the past

fifteen years (Figs 1–2).1 Many treasures and hoards were found on the hill

located not far from the so-called Amber Road, an ancient route that follows

the valley of the Gyöngyös Stream (Fig. 10. 1). Many researchers had set

themselves the task of cataloguing and assessing these assemblages;2 however, a

final, conclusive catalogue still awaits publication. Shortly after their discovery,

some parts of these hoards were “recycled”: they were melted down and used

for producing other artefacts (for example in the bell foundry of Pfistermeister

in K szeg).3 Another part has been lost forever, while yet another part was

purchased for private collections (Rezs Széchenyi, Kálmán Miske4) or for

public collections abroad (Graz, Vienna5) because their finders sold them. A

small part of these treasures and hoards was given to the former Museum of Vas

County in Szombathely (present-day Savaria Museum). Some of the treasures

were sent to the Hungarian National Museum.6 This short monograph focuses

on one particular assemblage, namely the golden treasure that was discovered in

1929 in the course of an archaeological excavation conducted by Baron Kálmán

Miske. Before discussing the findspot and the find circumstances, a brief detour

on the relationship between Kálmán Miske (Fig 6. 1) and the archaeological site

on the St. Vid Hill of Velem seems in order.

This archaeological site was placed on the map of Hungarian archaeology

by Flóris Rómer, the “founding father” of Hungarian archaeology. In 1869, he

collected fragments of Roman clay water pipes on the hill, which he perhaps gave

to the collection of the Benedictine gymnasium of K szeg.7 However, Kálmán

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

ILON 2007a; ILON 2013a.

CZAJLIK 1993, esp. 317–327; ILON – KÖLT 2000, note 5; FEKETE 2008, 525–540.

MISKE 1925, 46; CZAJLIK 1993, 326; FEKETE 2008, 527.

MISKE 1925, 47.

Miske too donated some artefacts to Vienna. Cf. FOLTINY 1958, 1.

MISKE 1897, 13; MISKE 1925, 47.

CHERNEL 1877, 15.

�10

Miske can undoubtedly be regarded as the scholar who devoted much of his efforts

to unearthing the archaeological relics on the hill and to presenting the findings

to the international scholarly community. He was born on November 25, 1860,

the sixth child of a landowner in Bodajk, Fejér County. His father was the Lord

Lieutenant of Moson County. Maybe this was the reason that he was obliged to

attend the Academy of Agriculture in Mosonmagyaróvár,8 in preparation for the

future management of his family’s property. At the same time, in my opinion, this

academic background explains why he was so open toward geology, pedology

and, in this context, chemistry in the course of his archaeological career. We can

understand his positive attitude towards chemical analysis,9 and geological10 and

pedological11 research in this light.

That he moved to K szeg is evidenced only by a letter dated to 1890, which

he addressed to Kálmán Chernel, the city’s eminent historian. Both of them were

highly educated and spoke several languages, they were devoted to history, and

were passionate collectors of ancient relics, hoards and antiquities. In this letter,

he also inquired about Sarolta, his future wife.12 After his father’s death, Kálmán

Miske sold his property in Bodajk in 1900 and created a life for himself in K szeg.

He had one son from his marriage.13 Through the mediation of the Chernel family,

he became acquainted with the Prince Esterházy14 and Count Zichy families, which

added to his already wide-ranging social connections, initially created through his

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

VÁGUSZ 2010, 58–59.

See Kálmán Miske’s unpublished report on the analysis performed by chemist Dr. Ernst

Söwy (Silesia): “Analysisek a Velem Szt. Vid 1901. évi szakszerű ásatása alkalmával

situsban lelt tárgyakról” [Analyses of artefacts found in situ during the professional

archaeological excavation conducted on St. Vid Hill in 1901]. The final section of the

report notes that Dr. Otto Helm (Gdańsk) will be performing the analysis of resins.

KVM Local History Archives, inv. no. 1484/XXXIX/101; MISKE 1908, 20, 26–34.

On March 18, 1908, he applied to the District Mining Inspectorate for the renewal of

his license and for the extension of the activity area to Sopron and Veszprém Counties.

KVM Local History Archives, inv. no. 1388/XXXIX/4.

In 1931, he commissioned the Hungarian Royal Chemical Institute to perform the

analysis of soil samples and to prepare a pedological map for the Musuem of Local

History and Homeland Education to be established in K szeg. This is reported in a letter

dated May 1933 addressed to the Mayor of K szeg. KVM Local History Archives, inv.

no. 790/XX/22.

Their wedding was held on April 10, 1894.

VÁGUSZ 2010, 58.

This explains why he dedicated his monograph on Velem (MISKE 1907, 1908) to the

“Honourable Prince Dr. Miklós Esterházy, as a token of friendship and respect”.

�11

father’s role as Lord Lieutenant. Also, his baronial rank provided solid grounds

for his career in the foundation and general management of museums and in the

discipline of archaeology. His donations to the Museum of Vas County, which

started its activity in 1908, made him its founder and thus he became the keeper

of the collection of antiquities from October 12 the same year;15 he was the very

first secular director of the museum from March 12, 1912, to March 15, 1943,

the day he passed away in K szeg. He was the founder of the Museum of Local

History and Homeland Education in K szeg that was opened to the public in May

1932, and he also served as Chairman of its Board of Development beforehand.16

In the first half of the 1890s, Baron Miske had a personal knowledge of the

archaeological relics found on the St. Vid Hill, because he noted the following

in 1896: “After various acquisitions, my collection slowly expanded and, due to

limited space, I was forced to place the pieces into a glass case in the hallway of

my home. After seeing my collection, a peasant woman from Velem informed

me that similar antiquities turned up oft-times in their village, and that some of

the peasants made a very good living from selling the antiquities, which fetched

a good price. During a visit to the place, I was able to see this with my own eyes.

The prehistoric settlement, which seems to be an inexhaustible source of artefacts

that has been exploited for years, is located in the northwestern part of Velem, on

a lone peak, where the castle of the infamous and dreaded Németujváry kindred

stood formerly, but where today you find a place of pilgrimage, a chapel dedicated

to St. Vid, where artefacts bearing witness to past centuries and millennia can be

found at a depth of 1 to 2 meters. I successfully collected many fascinating minor

finds for my collection during the years [my italics].”17

The name of the peasant woman mentioned by Baron Miske was Mrs. György

Kápiller. Later, Miske wrote the following about their meeting, the artefacts, and

their collectors: “Mrs. György Kápiller of Velem, who frequently delivered butter

to my home, admired [the bronze artefacts of Miske’s collection in the glass case]

and told me that her neighbour, Mihály Szigeti Molnár usually collected things

like these in the settlement and said that they were from St. Vid [Hill]. This was on

April 12, 1896. While ploughing his land, János Bóna of Velem found a sizeable

assemblage of bronze objects in a large vessel at the end of the same year.”18 The

majority of these artefacts were acquired by Kelemen Kárpáti, Chairman of the

15

16

17

18

ILON 2009, 39, 65.

KÁROLYI 1990, 402–403; ILON 2002a, 617.

Miske 1896, 250.

MISKE 1925, 46–47; CZAJLIK 1993, 318; FEKETE 2008, 528.

�12

Cultural Society of Vas County and later director of the Museum of Vas County,

for the planned museum in Szombathely, while another part was purchased by

Kálmán Miske for the Hungarian National Museum.

After this information had been divulged by the peasant woman, Bonya19/

Bónya (and not Bóna as recorded by Miske in the above passage) obviously

considered selling the bronze finds to Baron Miske for a hefty sum. The villagers

regarded the baron as something of an eccentric. In May 1896, Miske wrote the

following: “On the 18th day of this month, J. B. of Velem paid me a visit and

brought clay vessels with him as well as many fragments of sickles, knives and

coils for sale. After I purchased them, he informed me, to my joy, that he had

even larger intact pieces in his house.”20 As a cultured gentleman, or simply as a

careful amateur collector who jealously guarded his sources from other potential

buyers (we must not forget that the museum of Szombathely did not exist at the

time,21 and Miske became the keeper of the collection of antiquities only after

1908), Baron Miske only disclosed the initials (J. B.) of the peasant from Velem

in the quoted passage in Archaeologiai Értesít .

In 1896, in cooperation with Count Rezs Széchenyi and Kelemen Kárpáti,

Miske conducted what we would today call a control excavation, funded from

his own pocket, on the findspot of Hoard I (a and b), as it was then called.

This excavation unfortunately ended with no results. The first state-subsidised

archaeological excavation, which was supervised by Kárpáti and Miske, took

place in July 1898. These excavations, funded by the central budget, were

conducted until 1915.22 From 1901 onwards, archaeological excavations took

place under Miske’s supervision (Fig. 5), lasting for several days or weeks

each year. In 1902/03, anthropologist Aurél Török, lecturer at the University of

Budapest, assisted Miske; they published the burials dating to the Hunnic Age

unearthed on the hill.23 Lajos Bella of Sopron, who participated as the assigned

representative of the Hungarian National Museum, was Miske’s colleague in many

excavation campaigns. Miske’s assistant in the 1910s was Gilbert Neogrády, the

co-keeper of the collection of antiquities in the Museum of Szombathely.24 The

19

20

21

22

23

24

The cadastral map (Parzellen Protocoll Gemeinde Velem 1857) specifies the name of

the proprietor spelt as “Bonya”.

MISKE 1896, 252.

The museum was opened on October 11, 1908. TÓTH 2009, 28–29.

MISKE 1925, 47.

MISKE 1903, 1904.

MISKE 1925, 48.

�13

archaeological excavations that lasted until 1929 under his supervision were not

continued due to World War 1, the turmoil of the ensuing years (1919–1920), the

drastic diminution of his private wealth, his advanced age, the gradual loss of

his social relations with high society, and the incomprehensible antipathy of the

younger generation of archaeologists.25 Nonetheless, he successfully managed to

carry on his archaeological research as a result of the funding granted by financial

institutions of Szombathely (1921), the support of the county bishop (1922),26

and by renewed state subsidies from 1923 onwards.

Miske conducted and documented his archaeological fieldwork with a

meticulous attention to detail. Nothing proves this better than his article in the

1909 issue of the specialist methodological periodical Múzeumi és Könyvtári

Értesít [Museological and Library Journal] published by the Ministry of

Culture.27 Regrettably, his archaeological fieldwork in Velem is documented by a

few photographs only (Fig. 5),28 a report that includes a chemical analysis, certain

passages in the field diary of the archaeological excavations of 1901,29 a portion

of the survey of the burials dating to the Hunnic Age, a few financial reports

on the allocation of the state subsidy granted by the Museum of Vas County,

the incomplete annual reports and acquisitions registers of the same museum,30

and his incomplete notes with regard to the golden treasure. These documents

25

26

27

28

29

30

In his letter dated May 22, 1929, the President of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences

informed Miske that the Archaeological Commmittee of the Academy would not

recommend the support of his archaeological research in Velem. If, for any reason,

support should nonetheless be granted, the Committee would reserve its right to

supervise the archaeological research and the Museum of Vas County would not be

given a free hand to publish the results. SM Department of History, letterheaded paper

of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, originally filed under no. 1314/1929, among

the univentoried records. Ferenc Tompa played no small role in the unfavourable

evaluation of Miske’s work, which he admitted, very diplomatically, in his obituary of

Miske. Cf. TOMPA 1943; for the hostile attitudes of the period’s Hungarian scholarship

at the time, cf. KÁROLYI 1990, 402.

MISKE 1925, 49.

MISKE 1909.

For instance, the photograph recording the excavation of prehistoric furnaces,

published by KÁROLYI 1990, 405.

The single field diary known to me. written during the archaeological excavation of

1901, is in the KVM Local History Archives, inv. no. 1477/XXXIX. 94, 1478/XXXIX.

95.

E.g. from 1913; cf. ILON 2009, Fig. 7

�14

have been preserved in many different institutions.31 It seems to me that large

portions of Baron Kálmán Miske’s archaeological documentation, finished and

incomplete manuscripts,32 drawings and descriptions of artefacts connected with

Velem either still lurk undiscovered in various archives or have been lost forever

to archaeology.33

Realising the significance of this archaeological site, and in an effort to protect

it from the hunger for metals and metal ore in Hungary after the Treaty of Trianon,

Baron Miske, far ahead of his time, solicited the Deputy and Lord Lieutenant of

Vas County in October 1923 to declare the hill and the 1 to 3 km wide zone of

land around it a scheduled monument or a protected/conservation area as it would

be defined today. Only agriculture would be permitted in that particular zone and

any research would exclusively be carried out by the Museum of Vas County

and/or any other third party permitted to do so by the museum.34 However, the

ministerial decree for the protection and conservation of the archaeological site

only was only issued in the late 1960s and was restricted to the hill.

31

32

33

34

Documents housed in the City Museum of K szeg, the Savaria Museum, the

Archives of Vas County, the Archives of K szeg of the Hungarian National Archives

(Szombathely) and in the Hungarian National Museum as well as the documents from

the Department of Archaeology of the Eötvös Loránd University, now in the possession

of Mária Fekete.

Among these, Vols II and III of his monograph on Velem are undoubtedly the

most important. In its three-page leaflet promoting Vol. I, the Carl Konegen

publishing house of Vienna wrote the following: “Im zweiten Band wird über die

systematischen Grabungen berichtet und die Altersfolge der Funde erörtert werden.

Der dritte Band wird über den Fundort und die dort vorkommenden Funde anderer

Art, über die botanischen, zoologischen und antropologischen Verhältnisse, über die

Untersuchungen der Schlacken und über sonstige spezielle Fragen Aufschluß geben.”

KVM Local History Archives, uninventoried leaflet.

During the years of the Great War, a part of the building of the Museum of Vas County

was used as a school (MISKE 1925, 50), but extremely bad conditions existed during

the years of World War 2 as well. László Szakonyi, the former laboratory assistant of

the museum and later its first official conservator, who lived in the building, hid the

gold artefacts of Velem in a chest in his apartment, to prevent them being found by

soldiers and looters. KISS 2009, 329.

KÁROLYI 1990, 401; ILON 2009, 51. The undated draught version of a letter addressed

to the Deputy Lord Lieutenant specified a range of 1 km. See KVM Local History

Archives, inv. no. 393/XXXIX/9. It is possible that he had sent a letter to the Lord

Lieutenant as well, in order to get a larger area protected.

�15

1.2 Kálmán Miske and the discovery of the golden treasure

Part of Miske’s manuscript, preserved as a result of fortunate circumstances, but

earlier unknown to scholarship, describes the date and findspot of the golden

treasure relatively accurately.35 This part of Kálmán Miske’s letter of eight pages,

written in late 1929 and addressed to Count Albert Apponyi, former Minister

of Religion and Public Education, reports the following (Figs 7–9):36 “the

archaeological excavation on the St. Vid Hill in the summer of this year brought

to light the prehistoric iron mine. [Because research of this type is a special

branch of archaeology and not all archaeologists are predisposed to this branch]

... we excavated a cultural stratum that would satisfy the curiosity of the majority

of our visitors as well.” The trial trenches opened under Miske’s supervision to

reveal the layers were funded by the Ministry of Religion and Public Education

(see Appendix 2) during a planned four-day campaign37 as a result of efficient

“lobbying” by Ferenc Tompa (1893–1945, Fig. 6. 2), Miske’s former assistant

in Szombathely, who was by then working in the Hungarian National Museum.

35

36

37

I had earlier, inaccurately as it turned out, located the findspot near the chapel. ILON

2007a, 282; CZAJLIK 1993, 327. I discovered the letters written by Kálmán Miske that

specified the findspot of the treasure under nos 1426/XXXIX. 43 and 1942/XXXIX.109

in the KVM Local History Archives on October 1 and 21, 2013.

The following section of the letter (KVM Local History Archives, inv. no. 1426/

XXXIX. 43) allows the identification of the minister, as there is a reference to a state

subsidy granted twenty years earlier. We know the minister held this post between April

8, 1906 and January 17, 1910: “[…] I shall again pay a visit to Your Honour and request

the generous patronage of your lordship for St. Vid Hill of Velem as two decades ago”

[my italics]. One part of the letter, four pages (inv. no. 1942/XXXIX.109) was found

in a bundle of documents tied up with a string, labelled “Incomplete manuscripts from

Kálmán Miske’s bequest”. The addressing of “Your Honour” can be found here too.

Miske asked for another state subsidy for the purpose of further research on the iron

mine he had discovered; this part of the letter is unrelated to the six pages of another

letter about the golden treasure. See the list of Hungarian ministers of public education:

http://hu.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magyarorsz%C3%A1g_oktat%C3%A1s%C3%BCgyi_

minisztereinek_list%C3%A1ja#Vall.C3.A1s-_.C3.A9s_k.C3.B6zoktat.C3.A1s.

C3.BCgyi_miniszterek_.281867-1918.29 (accessed October 2, 2013).

Kálmán Miske’s letter of July 10, 1929, addressed to Ferenc Tompa is in the

uninventoried material of the HNM Archaeological Archives; Tompa’s bequest, box 1.

I am grateful to Dr. László Szende, director of the department, for calling my attention

to this letter.

�16

Who were the visitors mentioned in Miske’s letter? They were German

and Austrian archaeologists and scholars who were attending an international

conference, for whom Tompa organised an excursion; they visited St. Vid Hill

on September 5, 1929 (see Appendices 1–3).38 And where was the trial trench

opened to illustrate the chronology of the site? In his letter, Miske described

the site as follows:39 “It was something of a headache to select the appropriate

location. I wanted to dig in an area familiar to me, which was now covered

by a young forest; this was a place known to me, where I had conducted an

archaeological excavation in 1904 and which would reveal 2.1–2.5 meters thick

cultural layers overlying each other.40 But I had to give up this idea.” This is

because he would have had to remove an immense volume of earth from the area

(30–35 m²) and, also, the owner of the forest would have to be compensated.

These factors would have led to excessively high expenses, which he would not

have been able to finance. Therefore, Miske opted for a location where, despite

the thin cultural layer, the orientation of the three different terraces (“the terracing

of the site was oriented variously”) could be presented. His letter continues as

follows: “Also for this reason, nearly 16 years ago, I decided to continue the

excavation of the area that I had explored a year before the outbreak of Great War

[1913]: an upper terrace that contained a late La Tène layer with a layer of the

First Iron Age underneath, and where I had the opportunity to find and identify a

period preceding the Iron Age, so typical of our archaeological site, and a lower

terrace where the pre-Iron Age layer so typical for our site would be found under

the middle La Tène layer. Choosing this location seemed to be appropriate for

another reason, namely because it lies in the immediate vicinity of Szt. Kut [a

well], where we have already selected a convenient place for the afternoon tea of

our distinguished guests, who by that time would be exhausted by the mountain

climb and would be hungry, thirsty, and thus in need of some recovery. It seems

that my choice was inspired by my personal patron of the St. Vid Hill because I

was very fortunate to find the rectangular foundation of a late La Tène dwelling

on the upper terrace and the burnt remnants of a round, sunken hut from the Late

38

39

40

Relevant letters are kept among the records of the museum’s history, SM Department

of History, file no. 70, 74–75/1929. Correspondence of Tompa and Miske, list of

participants.

KVM Local History Archives, Inv. no. 1942/XXXIX.109; incomplete document.

As far as I know, a similarly thick layer sequence comparable to the one uncovered by

Miske has since only been discovered on the plateau of the hill, on the terrace under

the chapel. Cf. FEKETE 1986, 59–63, Taf. 10.

�17

Bronze Age on the lower terrace, and what is more, I found a remarkable and

valuable golden treasure during our work [my italics].” (Fig. 9).

The gold treasure, therefore, was discovered a few days before the arrival of

the guests, in the last days of August or the first days of September.

His letter continues as follows: “There is a significant chronological difference

between the period of manufacture and the deposition of the gold band. It was

created by the twisted gold wire technique, and its ornamentation, representing

the most advanced bronzeworking technique, determines its period of production.

Thus, this artefact can be dated to the Late Bronze Age at the earliest or to the

late period of the Early Iron Age at the latest. It was therefore made sometime in

1800–1400 BC. However, its findspot definitely lay in a layer of the late La Tène,

more specifically, it was hidden in a spot marked by an upright stone slab in the

corner of an unearthed dwelling. This jewellery was not used for the purpose

of adornment, but was rather a buried treasure, a hoard of valuables amassed

by its former owner. ... If, in this report, I be allowed a flight of fancy, we may

imagine that this jewellery was one of the mortuary gifts placed in the burial

of a prehistoric inhabitant of the St. Vid Hill of Velem and that it had come to

light during the chance discovery of the burial by a late descendant of the late

La Tène period. Bronze mortuary gifts were not considered to have had any

value and were left undisturbed; only golden treasures that had real value were

appropriated. However, it was not used for the purpose of everyday wear, but was

instead hoarded because of its obvious value. This should explain why the band

was folded, why the masterfully crafted adornment of twisted gold wire spirals

was in such a sorry state in its secret hiding place.” (Fig. 9).

The information related to the treasure in the letter reveals that (a) the trial

trench was dug in an area which Miske knew well in terms of its topography

and stratigraphy since 1913 because he was still intrigued by Hoard I, but at the

same time, he sought to find a spot near the spring that would be convenient for

his guests; (b) the trial trench cut across three terraces; (c) the third, lowermost

terrace lay roughly at same level as the spring; (d) the golden treasure was buried

underneath an upright stone slab in the corner of a late La Tène dwelling on the

highest terrace cut by the trial trench.

In his letter, Miske calls Ferenc Tompa his beloved student, who would publish

a report on the golden treasure alongside other artefacts (bronze pins, a bronze

arrowhead, iron finds, a Celtic brooch and potsherds) found on the archaeological

site. He also reported that vessel fragments were placed against the section

�18

wall and that the visiting scholars were very much pleased and appreciated the

opportunity to take them.

In his letters dated October 3 and 18, 1929, addressed to Ferenc Tompa

(see Appendix 4), Miske reported on the gold assemblage.41 More precisely, he

proposed that some compensation be paid to the owner (regretfully not named) of

the land that had yielded the gold objects and also recommended that its amount

be moderate in order to avoid looting by locals. Simultaneously, he asked Tompa

to publish a report on the treasure, verified by his letter dated January 8, 1930,42

in which he asked Tompa where and when he wished to publish this report.

However, Tompa’s response came in the form of his study in Bericht der RömischGermanischen Kommission, which contained an extremely brief description of

the assemblage, which hardly did any justice to the splendid artefacts.43

In an entry on page 84 of the inventory book of the Museum of Vas County

(Fig. 11. 1) written on March 27, 1941, Amália Mozsolics noted the following

regarding the find circumstances: “It was allegedly discovered by a tree in 1929.”

This is natural in a forested area, but reveals little about the find circumstances. In

response to a question asked by Mozsolics in her letter dated April 23, 1941 (see

Appendix 5) concerning the findspot of the treasure, Ferenc Tompa did not provide

additional information.44 In her book published in 1950, Amália Mozsolics noted

the following as regards the findspot of the treasure: “Baron Kálmán von Miske

fand im Jahre 1929 bei einer Probegrabung in Velem auf der obersten Terasse am

südlichen Abhang unter der Szent Vid (Sankt Veit) Kapelle unter zwei kleineren

41

42

43

44

The gold artefacts are first mentioned in Miske’s letter (no. 3), to be published in

Mária Fekete’s Leletek és levelek [Artefacts and Letters]. In another letter (no. 5),

he explains that in view of the sensational assemblage, the excessive expenses of the

reception of the foreign archaeologists can perhaps be excused. These letters were

found in the de-accessioned material of the Department of Archaeology of the Eötvös

Loránd University and were given to Mária Fekete by András Mócsy, the then director

of the department. I would here like to thank her kind for her permission to quote these

still unpublished letters.

The letter can be found in the uninventoried material of the HNM Archaeological

Archives, Tompa’s bequest, Box 1.

TOMPA 1934–35, 105.

See the letter filed under no. 114/1929 in the Archives of the Savaria Museum. Quoted

by FEKETE 2007, notes 58 and 243. A copy of Mozsolics’s letter dated April 23, 1941,

addressed to Ferenc Tompa, university professor, filed under no. 1941/43, can be found

among the records of the museum’s history of the SM Department of History.

�19

Felsen den hier zu besprechenden Goldfund.”45 She essentially repeated the same

incorrect description in her monograph published in 1985.46 Although there are a

few terraces on the southern slope of the hill, no archaeological relics have been

found on any of them, and no investigation took place in that specific area. Part of

Baron Miske’s previously quoted letter makes it clear that the treasure was found

somewhere near the Szentkút Spring (Fig. 10. 3).47

Therefore, Amália Mozsolics did not receive additional information on the

precise findspot of the treasure. In fact, she believed that it had been found on the

terrace under the chapel on the opposite slope of the hill. The term “upper terrace”

can only be interpreted in the light of Miske’s letter – it was the uppermost terrace

cut by the trial trench that extended across three terraces. The lowermost terrace

can be assumed to have been located at the altitude of the spring. The description

of the slab of stone as a marker is confirmed by Miske’s above-quoted letter. It

is to be noted that Miske reported a single stone slab under which the gold finds

were hidden, not two.

I could verify that the treasure had indeed been found in the proximity of the

Szentkút Spring (Fig. 10. 3), as described in Miske’s letter, during the inspection

of the site on April 19, 2013, made together with Szilveszter Katona from K szeg

(Fig. 10. 6).48 Szilveszter Katona knew about the findspot of the treasure from

his grandfather, János Katona,49 a villager of Velem. In the 1960s and 1970s,

János Katona was the caretaker of the St. Vid Chapel (Fig. 10. 2). Szilveszter

accompanied him from the village up to the hill in his childhood. His grandfather

showed him the findspot of the treasure many times. While walking up the hill,

they drew water from the Szentkút well,50 fed by the Szent Vid Spring (Fig. 10. 3),

and continued walking east-southeast. After leaving the spring, the path, which is

in fairly bad condition today, but is still used as a tourist trail (Fig. 10. 4), passes

the ruins of a building (Fig. 10. 3) once used as a scout camp and then a pioneer

45

46

47

48

49

50

MOZSOLICS 1950, 7.

MOZSOLICS 1985, 213; as a result, I too believed, erroneously, that the findspot lay

near the chapel. ILON 2007a, 282.

KVM Local History Archives, inv. no. 1942/XXXIX.109.

I was told about him by Ferenc Derdák, surveyor of the Savaria Museum (the co-worker

of the museum from 1973 onwards), member of the French-Hungarian archaeological

team led by Gábor Bándi and Mária Fekete. I am most grateful to him for sharing this

information with me. Szilveszter Katona was born on April 9, 1952 and he currently

lives at 108 Várkör in K szeg.

He was born on February 25, 1895, and is buried in the cemetery of Velem.

BALOGH – VÉGH 1982, 73: geographical toponym no. 42.

�20

camp in the Socialist era.51 The path leads along the edge of the terrace to the

valley dirt track passing under the plateau of the hill in front of the steps leading

to the chapel. According to the cadastral map of 1963, János Katona’s land was

Plot 2930 and extended to the southeast, to Plot 2981, lying on the other side of

the dirt track. The golden treasure was found on a strip of land, Plot 2930, between

the path, the spring, and the dirt track. This would be on the left side if viewed

from the path and moving toward the chapel, that is 30–60 meters toward northnortheast according to Szilveszter Katona (Fig. 10. 6). His grandfather always

told him that the findspot lay “next to a common hornbeam bush … practically

underneath its leaves, almost no earth had to be dug out.” He never talked about

slabs of stone or rocks, at least his grandchild could not recall any mention of

these. His grandfather told him many times that “the promised compensation was

never paid.”

In the 1960s, the Bónya family owned a strip of land, Plot 2931, which

lay on two or three terraces of slightly varying altitude at the altitude of the

spring (!), north of and slightly lower than the land of János Katona, who was

their neighbour. When reading out the names of owners recorded in the Land

Registry to Szilveszter Katona on the site, he told me that this family, specifically

Lajos Bónya, was his grandfather’s neighbour. Therefore, in 1896, the peasant

woman from Velem was speaking about this piece of land, owned by the Bónya

family, and its neighbourhood where the bronze hoards were discovered, some

of which Baron Miske had purchased. From his meticulous review of the data,

Zoltán Czajlik52 identified the site where Hoard Ia and Ib, that is, the impressive

Hoard I had been found in April and May 1896 (Figs 3–4). In my view, Hoard Ia,

comprising nearly four hundred objects, was found in a large vessel on April 12,

while Hoard Ib, made up of jewellery items, was found in May, with the two lying

some 4.5 meters apart. This would conform to what Tudor Soroceanu described

as the duality of hoard deposition.53 With excellent archaeological sense, as

well as in the hope of finding another hoard, Kálmán Miske conducted another

excavation in 1913 and had a trial trench dug there as a presentation trench. He

also hired János Katona, the owner of one of the (neighbouring?) plots, to work

as an excavation labourer.

51

52

53

The digital cadastral map of the settlement dated 2006 still marks the two brick

buildings, but they no longer appear on the maps dated 2008 and 2010.

CZAJLIK 1993, 318, Fig. 1, Fig. 2a.

SOROCEANU 2011, 278, 281, Taf. 3.

�21

To sum up the subject of the “hoards and treasures” plots and their owners:

according to the list of properties and lands drawn up in 1857, Simon Bonya was

the owner of Plots 2991 and 2993 on the St. Vid Hill, which were most certainly

owned by János Bónya in 1911 under registration numbers 2448 and 2450.

Therefore, Miske purchased the first bronze finds discovered in Velem from the

former owner in 1896. These strips of land (Plot 2931 in 1963) concealed Hoards

Ia and Ib, and the neighbouring land owned by János Katona (Plot 2451 or 2452

according to the cadastral map and land registry of 1911, and Plot 2930 in 1963)

was probably where the golden treasure was found, most likely at the end of

August 1929, but quite certainly before September 5.

Thus, the location of the findspot of the golden treasure54 is corroborated by

two new pieces of information previously unknown to archaeological scholarship:

(a) Miske’s letter reports a trial trench next to Szentkút Spring; (b) Szilveszter

Katona confirmed this during our inspection of the site, noting that the owner of

the neighbouring land was called Bónya. Since then, we know from the countless

studies devoted to this subject55 that wet environments, the proximity of a river

or spring, were highly preferred locations to the peoples of the European Bronze

Age for presenting sacrifices (see Chapter 11, below).

In the light of the above, it is hardly surprising to find two pits, each roughly

one meter deep (Fig. 10. 5), perhaps dug by treasure hunters, about 15–25 meters

from the spring and the ruins of the scout camp, south-southwest of the

aforementioned path. It is impossible to tell whether they were dug before 1929,

after the discovery of the golden treasure, or no more than a few decades ago.

These pits are called “Miske pits” by the locals. However, it is my conviction that

(a) Miske did not dig pits, but opened proper trenches (see Fig. 5 and his cited

letter describing the planned excavation over a 30–35 m² large area and the trial

trenches that cut through the terraces), and (b) he had the necessary foresight to

always backfill his trenches to prevent any possibility of subsequent looting – not

even the locals would be able to identify them after a few years.

54

55

Gábor Bándi and Mária Fekete probably knew about this site from the recollections of

the locals of Velem because they had opened three of their trenches dug in the assumed

area of the golden treasure’s findspot.

For two more recent ones, cf. HANSEN 1997, 29–34; FONTIJN 2012, 49–68.

�22

1.3 Investigating the golden treasure:

Amália Mozsolics and Gábor Bándi

The first and still the fullest publication of the golden treasure, listing the then

known analogies, was the book by Amália Mozsolics (1910–1997), printed in

Basel (Fig. 6. 3).56 Funded by the Hungarian National Museum, she had virtually

completed the manuscript on the treasure in February 1944. This is attested by

her letter addressed to Ágoston Pável, appointed the director of the Szombathely

museum after Miske’s death57 (see Appendix 6). The publication of the monograph

meant that the pieces of the treasure became known to international research.

Amália Mozsolics learnt about the golden treasure in 1940/41 when, employed

by the Szombathely museum, she worked as an assistant to Miske, who rarely

made the journey to Szombathely from his K szeg home due to his advanced

age. Her task was to catalogue the museum’s prehistoric collection.58 She defined

the diadem as a belt in the inventory book (Fig. 11. 1). The first “conservation

and restoration” of the folded artefacts had been performed sometime before

the inventorying, and it practically involved the partial straightening out of the

diadem had been folded thirteen times, which probably caused additional damage

and modification to the piece, resulting in some loss of information. Mozsolics

glued a photograph of the diadem showing the “restoration” to accompany

the description in the inventory book of the modern museum’s predecessor

(Fig. 11. 1). A more thorough conservation, the full straightening out, was

performed between April 24 and August 5, 1943, by István Méri,59 a conservator

of the Hungarian National Museum at the time, who later became the leading

Hungarian archaeologist of the Middle Ages (Fig. 11. 2). Performed in Kolozsvár,

a few months after Miske’s death,60 the work itself was funded by the Hungarian

56

57

58

59

60

MOZSOLICS 1950.

See the records of the museum’s history, SM Deparment of History, inv. no. 1944/13.

Her entries in the inventory book opened by her are enriched by her drawings and the

photographs of the treasure. The pieces she did not inventory at the time such as the

fragments of the backplates of the treasure’a gold foils have remained uninventoried to

this very day. Gyula Nováki did not re-inventory them in 1954, during re-inventorying

campaign of the museum’s holdings.

MOZSOLICS 1950, 8. The receipt of the restored artefact is archived among the records

of the museum’s history. SM Department of History, inv. no. 111/1943 (former inv. no.

119/1943).

Museum director Ágoston Pável recorded it in the list of golden artefacts kept in the

museum dated May 11, 1944, which he authenticated (SM Department of Ethnography,

�23

National Museum.61 Méri had quite certainly mounted the diadem onto a backing

(Fig. 15. 1) because museum director Ágoston Pável made the following entry in

the 1944 gold inventory: “1 (one) gold head ornament (head band) mounted on a

circular base”.62 This backing was a crude copper plate (Fig. 13, Fig. 15. 1; see

Katalin T. Bruder’s conservation diary, below). This conservation and restoration

was undoubtedly performed on Amália Mozsolics’s initiative and request,

obviously with the consent and knowledge of Ferenc Tompa who had by then

become the respected head of a university department. Tompa’s tragic death in

1945 ultimately enabled the planned publication of Amália Mozsolics’s book. In

her excellent monograph,63 she dated the golden treasure to the Hallstatt B period

by associating it with the bronze hoard (Hoard I) from Velem (1896), the lost gold

plates of Hoard II from Ság-hegy, the treasure found in Várvölgy (Fels zsid),

and the Rothengrub assemblage. Later, she assigned the finds from Rothengrub,

Velem and Fels zsid to the Gyermely horizon (Mozsolics BVc, Ha A2).64

Several decades later, Gábor Bándi (1939–1988; Fig. 6. 4) studied the

gold foils. He published a short article in the 1976/8 issue of Művészet, an art

periodical, in which the photograph of the diadem was first published. On the

testimony of the photograph on page 29, the copper plate onto which the gold

foil had been mounted was covered with cloth/textile. It seems likely that metal

conservator Aladár Hesztera,65 who was employed by the museum and completed

his academic studies in those years, performed this work on Gábor Bándi’s

request. Regrettably, his thesis does not reveal any information relevant to this

study because it does not contain any photographs. Gábor Bándi presented the

assemblage of jewellery at an international conference on the Amber Road held

in Bozsok in 1982.66 He quoted a few additional analogies in his presentation and

61

62

63

64

65

66

filed under no. 47/1944. in the uninventoried material). Ethnographer Dr. Sándor

Horváth called my attention to this uninventoried bundle of documents, for which I am

greatly indebted to him. Cf, ILON 2009, Fig. 18.

Amália Mozsolics informed museum director Ágoston Pável about this in her letter

dated February 21, 1944.

See the list of gold artefacts (filed under no. 1944/13) cited above.

MOZSOLICS 1950, 24–25, 41.

MOZSOLICS 1981, 306; 1985. 59.

As suggested by his manuscript, “A Velem Szent-Vidi stelep aranydiadémája” [The

gold diadem from the prehistoric settlement on St. Vid Hill of Velem]. Undated. SM

Archaeological Archves, inv. no. 2147-07.

BÁNDI 1983.

�24

he also proposed an early date – the beginning of the Urnfield period – compared

to the one suggested by Amália Mozsolics.

The diadem mounted onto the bent, textile-covered copper plate (Fig. 13,

Fig. 15. 1) was displayed at the archaeological exhibition in Szombathely entitled

“Regions – Ages – Settlements: the Birth of the Town”, opened in October 1982.

The exhibition was dismantled in July 2014. It is conceivable that the missing

portions of the gold foil were restored by Aladár Hesztera with poor-quality

materials in an aesthetically questionable way in 1982 (Fig. 14. 1, Fig. 15.

2–3). The domed roundels were glued to plastic sheets (perhaps also by him)

rather carelessly (Fig. 18. 2). Regretfully, this “restoration” is not attested in any

currently known museum records. This, then, was the condition of the treasure’s

pieces before the new conservation work.

The new conservation project was carried out between 2004 and 2006 by

Katalin T. Bruder, the chief conservator of the Hungarian National Museum, who

died in 2012.67 It was my hope that her work would also provide answers to

several questions, some archaeometric in nature.

1. What was the original size and shape of the diadem?

2. Do the bronze patina marks on the reverse of the diadem and the thin

bronze backplate fragments originate from the backing of the gold foil?

(Similarly to Amália Mozsolics,68 I too believed that the bronze plates

were the backplates to the diadem and/or domed roundels).

3. Were the diadem, the four domed roundels, and the gold spirals

manufactured in the same workshop? In addition to typological and

manufacturing technological observations, it was my intention to resolve

this issue by a provenance study.

4. Based on their raw material, is there any connection between the Velem

assemblage and a particular group of gold finds analysed in large series

by international research?

The chief conservator received the diadem and the four domed roundels in

February 2004, and the gold wires, the gold spirals and the bronze backplates in

September of the same year.

67

68

DOMBÓVÁRI 2012, 293.

MOZSOLICS 1950, 7, Taf. III. 17–28.

�2 Description of the artefacts and the results of the new

conservation project

2.1 Description of the artefacts based on Kálmán Miske’s incomplete

manuscript, our observations69 and the results of the conservation

Kálmán Miske’s recently discovered manuscript dating from 1929 contains the

first description of the artefacts of the treasure.70 I shall cite the relevant passage

verbatim because it contains essential information and other important remarks:

“This gold assemblage, discovered through a stroke of good luck on

the St. Vid Hill of Velem, is made up of a folded band of pure gold

with a width of ca. 6 cm, whose length, give or take a little, is 80 to

100 cm, and an adornment of hopelessly tangled twisted gold wires

to which round gold discs had been attached to form a necklace. The

gold band as well as the round discs are decorated with circular and

twisted cable motifs. The gold threads of the necklace, as can be

concluded from its undamaged parts, were spirally twisted. The pure

gold used for its creation indicates three techniques of wire drawing,

which are as follows: triangle-shaped ∆, another one that also has D

thus ﬦcross-section and a commonly used ○ round cross-section.

The total weight of the gold artefact is … grm, of which the belt

band’s weight is … grm.

In any case, the manufacturing technique of this gold band and the

round gold plates is interesting because these incredibly thin plates

are attached to a bronze plate probably for the purpose of their

reinforcement, or perhaps merely to enhance the repoussé, seeing

that the bronze plates are just as thin. Regrettably, these thin bronze

69

70

I checked the smaller details together with metal conservator Csaba E. Kiss. In January

and February 2008, we examined the earlier gold artefacts from Várvölgy in the

Hungarian National Museum and the more recently discovered ones from the same site

in the collection of the Balaton Museum of Keszthely. I was assisted in the analysis of

the finer details of the goldsmithing techniques used for creating the foils by goldsmith

András Radics.

KVM Local History Archives, inv. no. 1942/XXXIX.109.

�26

plates are totally obsolescent [worn?] and were found in a most

fragmented condition.”

2.1.1 The diadem (Figs 12–16)

The thickness of the gold foil varies between 0.41–0.47–0.52 mm owing to

the repoussé decoration.71 The thickness of the folded-over foil at the edge is

0.7 mm. Originally, the gold foil was applied onto a bronze backplate, as shown

by folded-over edge and the scraps of the bronze backplates. The remnants of

the bronze backplate72 identified during the new conservation in three spots on

the reverse of the foil were not in their original position because the impressions

of the ornamental motifs on the corroded backplate do not correspond to the

decoration on the diadem in the same area. The flattened drawing of the diadem

(Fig. 12. 2) shows that it has an elongated, recumbent S shape, with one end

curving upward and the other downward. There is a pair of perforations on

each end of the foil (Fig. 16. 2), a pair under the peak in the middle (Fig. 16. 1)

and additional ones along the lower edge (Fig. 15. 2). The number of the latter

cannot be specified accurately owing to the damage caused by earlier folding.

The perforations were made with a punch from the reverse towards the obverse

bearing the decorative design (Fig. 16. 2), a not particularly elegant procedure.

The diameters of the perforations vary. The upper amorphous perforation on the

left end is 1.8 x 1.2 mm, while the lower one is 1.5 mm. The upper perforation

on the right end is pentagonal and measures 2.2 mm, while the one underneath it

is oblong shaped and measures 2.2 mm as well (Fig. 16. 2). Of the perforations

on the top, the one beside the concentric circle is triangular and measures 2 mm,

while the one interrupting the cable pattern is round and measures 1.2 mm

(Fig. 16. 1). The stamped decoration of the diadem is composed of concentric

circles combined with bosses in the centre (Figs 14–16), zigzag (Fig. 16. 3) and

cable patterns (see below, for a detailed discussion). The length of the flattened

diadem is 403 mm, its greatest height is 97 mm. The greatest diameter of the foil

in its “original” form after conservation is 193 mm; its weight is 23.09 g. Inv. no.

54.603.11, sample code: VD and V5. Formerly unavailable essential information

71

72

The thickness of the gold foil of the cap ornament (Goldhut) in the Museum für Vorund Frühgeschichte in Berlin is 0.06 mm (60 micron), while that of the neck ornament

in Berlin is 0.02 mm (BORN 2003b, 89, 95); the median thickness of the gold foil of the

cap ornament (Goldkegel) from Ezelsdorf is 0.08 mm (KOCH 2003, 99).

Cf. MOZSOLICS 1950, Abb. 1. 1, for a reconstruction drawing of the backplate.

�27

(such as weight) about the diadem and the other pieces of jewellery as well as

the first reconstruction of how it was worn appeared in the guide to an exhibition

organised in 2008 by the present author in collaboration with Marcella Nagy as

well as in the jubilee volume of the Savaria Museum in 2009.73

2.1.2 The domed roundels (Figs 17–20)

These artefacts have always been referred to as Scheibe (“disc”) in German

publications;74 however, given that their form is semi-spherical, the term domed

roundel seems more appropriate, especially in view of similar artefacts found

at Ippensheim–Bullenheimer Berg,75 Worms76 and Hammersdorf77 designated as

Buckel in German. Like the diadem, they were made of gold foil and similarly

mounted on a bronze backplate (Fig. 23), over which the gold foil was folded

back. A reconstruction of the gold foil and the backplate was published by Amália

Mozsolics over half a century ago.78 The domed roundels are framed by gold wire

wound around bronze wire as was observed and recorded by Miske in his letter

cited above.

The decoration and colour of each domed roundel pair (before conservation)

was identical, but the decoration and colour of the pairs differed. Amália

Mozsolics assumed that the lighter-coloured domed roundels (Figs 19–20;

MOZSOLICS 1950, Taf. II. 3–4, Pair II according to the current classification) and

the diadem of identical colour had been made of electrum using the same tools.79

Her contention was refuted by Katalin T. Bruder’s observations on colour (see

below), which has since been confirmed by the metal analysis too. A new theory

based on the visually identifiable traits and the assumed colour differences of the

treasure80 can thus be rejected as being entirely groundless.

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

NAGY – ILON – RÉVÉSZ 2008; ILON – NAGY 2009, 52–53.

MOZSOLICS 1950; BÁNDI 1983.

GEBHARD 2003, Abb. 2.

DAVID 2003, Abb. 2, 11–12.

DAVID 2010, 455–456, Abb. 11.

MOZSOLICS 1950, Abb. 1. 2.

MOZSOLICS 1950, 9.

FEKETE 2010, 394–398.

�28

Pair I (Figs 17–18)

This ornament pair was manufactured from gold foil and a bronze backplate. Its

colour, darker than that of the other pair, was caused by the staining of the gold

foil (see Katalin T. Bruder’s conservation diary, below).

Domed roundel 181 (Fig. 17. 1, 4, Fig. 18. 1; BÁNDI 1983, Abb. 3. 1 =

MOZSOLICS 1950, Taf. II. 1) lacks about one-sixth of its original size, which

probably broke off. Gold wire twisted around a bronze wire was set around its

edge. Six points of the attachment of the spiral survive. The diameter of the spiral

is 1.4 mm. A stamped design of seven concentric circles (Ringbuckel) in the

centre is framed by stamped cable and zigzag motifs. The diameter of the domed

roundel is 56 mm, its thickness is 0.41–0.6 mm. Its weight prior to conservation

was 3.16 g and 3.86 g after conservation, together with the Japanese tissue and

adhesive. Inv. no. 54.603.9, sample code: V1.

Domed roundel 4 (Fig. 17. 1, 4, Fig. 18. 2; BÁNDI 1983, Abb. 3. 2 =

MOZSOLICS 1950, Taf. II. 2) lacks about one-half of its original size. It

ornamentation is identical to the previous one. The diameter of the spiral placed

around its edge is 0.8–1 mm. Five points of its attachment survive. A fragment

of the bronze backplate can be seen on the reverse, but it was not placed in its

original position during conservation. The diameter of the domed roundel is

56 mm, its thickness is 0.51 mm. Its weight prior to conservation was 1.50 g and

4.87 g after conservation, together with the Japanese tissue and adhesive. Inv.

no. 54.603.8, sample code: V4. In 2012. I published a preliminary report on this

domed roundel pair earlier.82

Pair II (Figs 19–20)

This ornament pair was made of gold foil whose colour, prior to conservation,

was a slightly lighter yellow than of the previous pair.

Domed roundel 2 (Fig. 19, Fig. 20 1. 3; BÁNDI 1983, Abb. 4. 2 = MOZSOLICS

1950, Taf. II. 3) lacks two sections opposite each other. Gold wire twisted around

a bronze wire was set around its edge. The diameter of the spiral is 1.2 mm. Six

points of its attachment survive. A row of concentric circles was stamped around

its edge, followed by cable and zigzag motifs which frame a pattern of seven

stamped concentric circles in the centre. The diameter of the domed roundel is

81

82

The numbering was determined by the sequence of the artefact as a belt reconstruction

displayed at the permanent exhibition opened in October 1982; after its dismantling,

the conservator numbered them according to that sequence.

ILON 2012a.

�29

56 mm, its thickness is 0.8 mm. Its weight prior to conservation was 2.05 g and

3.56 g after conservation, together with the Japanese tissue and adhesive. Inv. no.

54.603.6, sample code: V2.

Domed roundel 3 (Fig. 19, Fig. 20. 2, 4; BÁNDI 1983, Abb. 4. 1 = MOZSOLICS

1950, Taf. II. 4) is identical with previous piece as regards its decoration. However,

a part has broken off and it has radial cracks on its surface. The diameter of

the gold spiral is 1 mm. Seven points of its attachment survive. The diameter

of the domed roundel is 56 mm, its thickness is 0.44 mm. Its weight prior to

conservation was 2.46 g and 3.93 g after conservation, together with the Japanese

tissue and adhesive. Inv. no. 54.603.7, sample code: V3. In 2013, I published a

preliminary report on this domed roundel pair.83

2.1.3 The bronze backplates (Fig. 23)

The bronze backplates served as reinforcements to both the diadem and the gold

foils of the domed roundels.84 Their total weight is 17.9 g, without the fragments

that were earlier glued to the plastic plates, making them irremovable and

immeasurable. Inv. no. 54.603.12.

2.1.4 The gold spirals (Figs 21–22)

A smaller portion are still spirals, but the majority was carelessly straightened

out either before the deposition and/or after their discovery,85 which, regrettably,

makes any interpretation of their function much more difficult or downright

impossible. They were attached to polystyrene plates and stored in a box, a rather

lamentable . Each piece was numbered and measured during their conservation,

and a better storage was also ensured.86 The total weight of the sixty-six gold

spirals is 49 g (Table 1). Inv. no. 54.603.10, sample code of the pieces selected

for analysis: Vel4, Vel5, Vel6.

83

84

85

86

ILON 2013b.

The mode of attachment of the backplates to the golden foils could be analysed by

modern technology (e.g. 3D scanning), but I had no means of using an instrument of

this type.

When Amália Mozsolics inventoried the pieces of the treasure in 1941, the spirals were

still entangled.

Their weight was not published earlier.

�30

Table 1: The weight of the gold wires

Number

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14.

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

Total

Weight (g)

9.3

1.8

0.2

1.3

0.6

0.2

1.6

0.2

0.4

0.4

0.1

0.2

1.0

0.6

0.5

0.4

0.2

0.2

2.1

0.4

2.3

0.2

49.0

Number

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

Weight (g)

<0.1

2.1

0.8

0.8

1.4

0.4

0.6

0.5

0.5

0.9

1.1

0.3

0.6

0.4

0.5

0.4

0.4

0.1

0.7

1.2

0.7

0.8

Number

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

Weight (g)

0.8

0.8

0.8

1.0

0.8

0.9

0.7

0.1

0.2

0.5

0.4

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.4

0.4

0.2

0.2

0.2

0.1

0.1

0.1

2.1.5 The weight of the treasure

The total weight of the surviving gold foils prior to conservation was 82.07 g.87

Can the original weight of the artefacts be estimated somehow? Yes, it can,

although we have to proceed very cautiously.

The weight of the diadem is 23.09 g. A piece of foil the size of a domed

roundel is missing from the diadem on its right side if viewed frontally and on its

left side if viewed according to how it was worn (Fig. 12, Fig. 14. 1, Fig. 15. 3),

87

Amounting to one-sixth of the total weight of the treasure mae up of thirteen gold

vessels found in Villena (Alicante, Spain). Cf. ARMBRUSTER 2012, 371.

�31

disregarding now the other minor damages (Fig. 15. 6). Based on the weight of

the light domed roundels, this missing portion must be at least 2.5 g. Therefore,

the original weight of the foil can be estimated as roughly 25.59 g.

Some of the domed roundels are also incomplete. In the case of Pair I

(Fig. 17), the average weight of each piece is ca. 3 g (V1: 3.16 g; V4: 1.50 g, but

the latter barely exceeds a half fragment). Their damage and missing portions

suggest a gold foil that must have been slightly heavier originally. The domed

roundels of Pair II (Fig. 19; V2: 2.05 g, V3: 2.46 g) suggest gold foils that had

an original average weight of ca. 2.5 g, but certainly below 3 g. In other words,

the weight of these four jewellery foils must have been 2 x 3 g or 2 x 2.5 g,

totalling roughly 11 g. It must be borne in mind that this figure does not represent

the pure gold weight because the gold spirals had been wound around a bronze

wire core. As far as the almost completely unravelled gold tangle weighing 49 g

in all is concerned (Fig. 21; some of the spiral fragments also contained bronze

wire cores!), its weight remains wholly uncertain because there is no information

about how much of it disappeared since its discovery in 1929.

Therefore, the reconstructed minimum total weight of the gold foils and

the surviving spiral wires is 85.59 g + x g, the latter representing the spirals

presumably lost.

2.2 Extract from Katalin T. Bruder’s conservation diary88

2.2.1 The first phase of the conservation project:

assessment of the condition of the artefacts

Diadem (sample code: VD and V5)

The gold foil of the diadem originally overlay the bronze backplate. The foil

was mounted onto the backplate by folding over an approximately 2 mm

wide strip along the edges. In our opinion, there must have been some organic

adhesive or filling between the bronze and gold plates, similarly to the “discs”;

this adhesive naturally broke down as time passed. Regrettably, the folded-over

part was carelessly flattened during previous conservation – the bronze remains

88

Together with chief conservator Csaba E. Kiss, we checked all the measurements

specified in the conservation diary on March 5, 2012.

�32

were perhaps destroyed at this time. Its restoration into its assumed original state

cannot be performed without damage.

During one of the conservation projects, the gold overlay was glued to a

crude copper plate having a thickness of 1 mm (359 g) (Fig. 15. 1). The missing

portions of the gold foil were filled with dental plastic (Kalloplaszt, Duracryl, or

some similar material). Acetone was used to remove this plastic, after which we

found that the gold foil had broken into several fragments at certain points. Traces

of iron corrosion were noted in the grooves of the design covering the surface of

the diadem.

There are two perforations on either end of the diadem, and two others

underneath the peak on top; additional perforations could be identified at four

points along the lower edge. It seems likely that the fractures occurred exactly

where there were perforations originally. The perforations were probably made

to fasten the diadem to a cap-like headwear, or to attach the bronze backplate and

the gold overlay to each other. The form of the perforations differs from those on

the “discs”.

Domed roundels (sample codes: V1, V2, V3, V4)

Acetone was used to detach the gold foils from the transparent, green plastic

plates (Fig. 18. 3; the adhesive was some sort of soluble and colourless lacquer).

The “discs” are not only incomplete, but were also fragmented when attached.

The adhesive could be removed with acetone and alcohol, but an unidentifiable

staining could only be removed by hand. Sodium hexametaphosphate was used

for the treatment of the stained and lacklustre surface of the gold foil. “Discs” 1

and 4 were stained brown,89 and the staining from these discs could be removed

for the greater part.

There was a round, bronze backplate underneath the gold foils, which was

almost completely destroyed, presumably due to previous treatments and during

the time they lay buried. The edge of the gold foil is wavy, has a fairly irregular

line, and is folded over the round bronze backplate along a 0.2 mm wide strip.

The twisted cable around the edge of the obverse of the gold-covered bronze

backplate was created by tightly winding a 1 mm wide gold strip around 1 mm

wide bronze wire without leaving any space (Fig. 21. 2–3). The twisted cable

thus created was attached by means of two, or perhaps three, bands laced through

a rectangular perforation cut into each “disc” (Fig. 17. 3). The distance between

89

Amália Mozsolics noted their darker colour. MOZSOLICS 1950, 8–9.

�33

the attachment points varies. The use of solvents for removing the “discs” from

the green plastic plates resulted in the gold overlay falling into many small

fragments, especially in the case of the two “discs” decorated with two concentric

circles (Pair II). We confirmed what had been merely an impression earlier,

namely that their previous refitting was rather erratic. The removal of many kinds

of adhesives90 was followed by the sorting of the fragments and their temporary

refitting to each other. We found that if the fragments were refitted accurately, the

restored object would be semi-spherical with a convex surface,91 instead of being

a flat and round object (Fig. 17. 4, Fig. 19. 2). The final refitting was made using

Japanese tissue coloured golden yellow in order to reinforce the artefact (with the

use of Planatol).

Gold spirals

They vary in size (the following figures are approximate because these spirals are

deformed in many cases).

– Spirals with round cross-section and a diameter of 1.09–1.12–1.25 mm,

made from a gold band of triangular cross-section wound tightly around a 1 mm

thick bronze wire. The width of the latter is 0.5 mm. Sample code: Vel4. These

spirals were used for creating three-lobed passmanterie-like patterns connected

by a gold band (Fig. 21. 2–3).

– Spirals with round cross-section and a thickness of 2.38–2.6 mm, made

from a gold band of triangular cross-section wound tightly around a bronze wire.

The latter did not include any that could be measured. Sample code: Vel 5.

– Spiral with flattened circle (rounded rectangle) cross-section, made from

gold band of triangular cross-section. The width of the spiral at each end is 3.7 mm

and 4.7 mm, and 2.4 mm, respectively. An additional similar piece, measuring 5.8

x 4.9 mm (Fig. 21. 2; MOZSOLICS 1950, Abb. 5. 1), made from a gold band with

triangular cross-section. Sample code: Vel6 (Fig. 21. 4). In our opinion, these

might have been wound around some sort of organic material such as a textile

90

91

Perhaps added by István Méri and Aladár Hesztera during their conservation work.

The same phenomenon, i.e. an earlier flattening and straightening of the ”Buckel”,

reflected by the radial cracks, fractures and creases, has been noted in the case of

several similar artefacts, e.g. Óbuda: MOZSOLICS 1950, Abb. 7. 1–2; Fels zsid:

MOZSOLICS 1950, Taf. VII. 8–10; Cófalva: MOZSOLICS 1950, Taf. VIII. 1–9, 11–12;

Moordorf: GOLD UND KULT 2003, Kat. Nr. 12.

�34

ribbon or leather strap because no remnants of a bronze backplate were found on

them. Comparable objects are known from the assemblage from Óbuda.92

Bronze plate fragments (Fig. 23; MOZSOLICS 1950, Taf. III, 17–28)

One part of the corroded bronze fragments was stored in a little plastic box (once

used to store typewriter ribbons) which was kept in the vault of the museum.

These fragments were the few entirely corroded scraps of the bronze backplates

reinforcing the reverse of the decorated gold overlay. These were corroded to

the gold overlay due to the nature of the material, although they did preserve its

pattern. Regrettably, the number of fragments is negligible compared to the size

of the gold overlay. In general, it is impossible to determine with any certainty

whether these fragments were attached to the diadem or the “discs” (and, more

specifically, to which of the latter), they are unsuitable for comparative metal

analyses or for far-reaching conclusions in this respect. The following could be

noted during their examination:

– One fragment, the largest of all, from the inner part of one of the “discs”, is

strongly deformed. Since the bronze is wholly corroded, this deformation

could only have occurred when the piece was still an intact, i.e. at the time

of its deposition at the latest.

– Relatively larger fragments (¼–½ cm²), most likely from the domed

roundel(s) have a domed surface, confirming that they were not flat discs,

but had a semi-spherical form typical of domed roundels.

– The fragments included a granule, a tiny spherule with a diameter of ca.