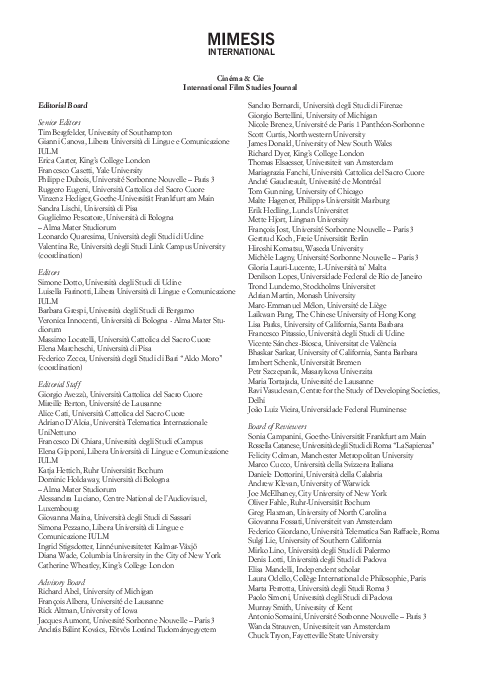

MIMESIS

INTERNATIONAL

Cinéma & Cie

International Film Studies Journal

Editorial Board

Senior Editors

Tim Bergfelder, University of Southampton

Gianni Canova, Libera Università di Lingue e Comunicazione

IULM

Erica Carter, King’s College London

Francesco Casetti, Yale University

Philippe Dubois, Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3

Ruggero Eugeni, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore

Vinzenz Hediger, Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main

Sandra Lischi, Università di Pisa

Guglielmo Pescatore, Università di Bologna

– Alma Mater Studiorum

Leonardo Quaresima, Università degli Studi di Udine

Valentina Re, Università degli Studi Link Campus University

(coordination)

Editors

Simone Dotto, Università degli Studi di Udine

Luisella Farinotti, Libera Università di Lingue e Comunicazione

IULM

Barbara Grespi, Università degli Studi di Bergamo

Veronica Innocenti, Università di Bologna - Alma Mater Studiorum

Massimo Locatelli, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore

Elena Marcheschi, Università di Pisa

Federico Zecca, Università degli Studi di Bari “Aldo Moro”

(coordination)

Editorial Staff

Giorgio Avezzù, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore

Mireille Berton, Université de Lausanne

Alice Cati, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore

Adriano D’Aloia, Università Telematica Internazionale

UniNettuno

Francesco Di Chiara, Università degli Studi eCampus

Elena Gipponi, Libera Università di Lingue e Comunicazione

IULM

Katja Hettich, Ruhr Universität Bochum

Dominic Holdaway, Università di Bologna

– Alma Mater Studiorum

Alessandra Luciano, Centre National de l’Audiovisuel,

Luxembourg

Giovanna Maina, Università degli Studi di Sassari

Simona Pezzano, Libera Università di Lingue e

Comunicazione IULM

Ingrid Stigsdotter, Linnéuniversitetet Kalmar-Växjö

Diana Wade, Columbia University in the City of New York

Catherine Wheatley, King’s College London

Advisory Board

Richard Abel, University of Michigan

François Albera, Université de Lausanne

Rick Altman, University of Iowa

Jacques Aumont, Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3

András Bálint Kovács, Eötvös Loránd Tudományegyetem

Sandro Bernardi, Università degli Studi di Firenze

Giorgio Bertellini, University of Michigan

Nicole Brenez, Université de Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne

Scott Curtis, Northwestern University

James Donald, University of New South Wales

Richard Dyer, King’s College London

Thomas Elsaesser, Universiteit van Amsterdam

Mariagrazia Fanchi, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore

André Gaudreault, Université de Montréal

Tom Gunning, University of Chicago

Malte Hagener, Philipps-Universität Marburg

Erik Hedling, Lunds Universitet

Mette Hjort, Lingnan University

François Jost, Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3

Gertrud Koch, Freie Universität Berlin

Hiroshi Komatsu, Waseda University

Michèle Lagny, Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3

Gloria Lauri-Lucente, L-Università ta’ Malta

Denilson Lopes, Universidade Federal de Rio de Janeiro

Trond Lundemo, Stockholms Universitet

Adrian Martin, Monash University

Marc-Emmanuel Mélon, Université de Liège

Laikwan Pang, The Chinese University of Hong Kong

Lisa Parks, University of California, Santa Barbara

Francesco Pitassio, Università degli Studi di Udine

Vicente Sánchez-Biosca, Universitat de València

Bhaskar Sarkar, University of California, Santa Barbara

Irmbert Schenk, Universität Bremen

Petr Szczepanik, Masarykova Univerzita

Maria Tortajada, Université de Lausanne

Ravi Vasudevan, Centre for the Study of Developing Societies,

Delhi

João Luiz Vieira, Universidade Federal Fluminense

Board of Reviewers

Sonia Campanini, Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main

Rossella Catanese, Università degli Studi di Roma “La Sapienza”

Felicity Colman, Manchester Metropolitan University

Marco Cucco, Università della Svizzera Italiana

Daniele Dottorini, Università della Calabria

Andrew Klevan, University of Warwick

Joe McElhaney, City University of New York

Oliver Fahle, Ruhr-Universität Bochum

Greg Flaxman, University of North Carolina

Giovanna Fossati, Universiteit van Amsterdam

Federico Giordano, Università Telematica San Raffaele, Roma

Sulgi Lie, University of Southern California

Mirko Lino, Università degli Studi di Palermo

Denis Lotti, Università degli Studi di Padova

Elisa Mandelli, Independent scholar

Laura Odello, Collège International de Philosophie, Paris

Marta Perrotta, Università degli Studi Roma 3

Paolo Simoni, Università degli Studi di Padova

Murray Smith, University of Kent

Antonio Somaini, Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3

Wanda Strauven, Universiteit van Amsterdam

Chuck Tryon, Fayetteville State University

��vol. XVI, no. 26/27, Spring/Fall 2016

CINÉMA&CIE

INTERNATIONAL FILM STUDIES JOURNAL

Post-what? Post-when?

Thinking Moving Images Beyond the Post-medium/Post-cinema Condition

Edited by Miriam De Rosa and Vinzenz Hediger

MIMESIS

INTERNATIONAL

�Cinéma & Cie is promoted by

Dipartimento di Lettere, Lingue, Arti. Italianistica e Culture Comparate, Università degli Studi di Bari “Aldo Moro”; Dipartimento di Lettere, Filosoia,

Comunicazione, Università degli Studi di Bergamo; Dipartimento delle Arti

– Visive Performative Mediali, Università di Bologna – Alma Mater Studiorum;

Dipartimento di Scienze della Comunicazione e dello Spettacolo, Università

Cattolica del Sacro Cuore; Dipartimento di Arti e Media, Libera Università di

Lingue e Comunicazione IULM; Dipartimento di Civiltà e Forme del Sapere,

Università di Pisa; Università degli Studi Link Campus University, Roma;

Dipartimento di Studi Umanistici e del Patrimonio Culturale, Università degli

Studi di Udine.

International PhD Program “Studi Storico Artistici e Audiovisivi”/“Art History and Audiovisual Studies” (Università degli Studi di Udine, Université

Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3).

SUBSCRIPTION TO Ciném a & Cie (2 ISSUES)

Single issue: 16 € / 12 £ / 18 $

Double issue: 20 € / 15 £ / 22 $

Yearly subscription: 30 € / 22 £ / 34 $

No shipping cost for Italy

Shipping cost for each issue:

EU: 10 € / 8 £ / 11 $

Rest of the world: 18 € / 13 £ / 20 $

Send orders to

commerciale@mimesisedizioni.it

Journal website

www.cinemaetcie.net

© 2017 – Mimesis International

www.mimesisinternational.com

e-mail: info@mimesisinternational.com

isbn 9788869770555

issn 2035-5270

© MIM Edizioni Srl

P.I. C.F. 02419370305

Cover image:

François Dourlen

Instagram @francoisdourlen

www.facebook.com/lesphotosdefrancois

�Contents / Table des matières

Post-what? Post-when?

Thinking Moving Images Beyond the Post-medium/Post-cinema Condition

p.

9

Miriam De Rosa and Vinzenz Hediger, Post-what? Post-when?

A Conversation on the ‘Posts’ of Post-media and Post-cinema

21

Shane Denson, Speculation, Transition, and the Passing of Post-cinema

33

Ted Nannicelli, Malcom Turvey, Against Post-cinema

45

Sabrina Negri, Simulating the Past: Digital Preservation

of Moving Images and the ‘End of Cinema’

55

Rachel Schaff, The Photochemical Conditions of the Frame

65

Saige Walton, Becoming Space in Every Direction:

Birdman as Post-cinematic Baroque

77

Monica Dall’Asta, GIF Art in the Metamodern Era

New Studies

91

Diego Cavallotti, Elisa Virgili, Queering the Amateur Analog Video Archive:

the Case of Bologna’s Countercultural Life in the 80s and the 90s

107

Simone Dotto, Notes for a History of Radio-Film:

Cinematic Imagination and Intermedia Forms in Early Italian Radio

121

Francesco Federici, The Experience of Duration and the Manipulation

of Time in Exposed Cinema

135

Kamil Lipiński, Archival Hauntings in the Revenant Narratives

from Home in Péter Forgács’ Private Hungary

149

Projects & Abstracts

165

Reviews / Comptes-rendus

177

Contributors / Collaborateurs

��Post-what? Post-when?

Thinking Moving Images Beyond

the Post-medium/Post-cinema Condition

��Post-what? Post-when?

A Conversation on the ‘Posts’ of Post-media and Post-cinema

Miriam De Rosa, Coventry University

Vinzenz Hediger, Goethe-Universität, Frankfurt am Main

Abstract

The text retraces the current debate around the notions of post-cinema and

post-media. Employing a dialogic approach, the editors propose a theoretical

framework to provide context for the main contributions on these topics published in recent years, highlighting the conceptual connections to the previous

scholarship. The resulting relection serves as a platform to introduce and situate

the contributions to this special issue. In particular, the editors propose to use

the term coniguration to account for the various aspects and facets of contemporary cinematic experience.

The idea for this special issue of Cinema&Cié came out of a dialogue. Having

both worked on questions of post-media and post-cinema for some time, and

for a time in the same institution, we found that one point where our interests

intersected was the question of temporality, i.e. the contours of the historical

break suggested by the preix ‘post-’. Usually, productive intersections involve

twists, negotiations, or even jolts. As beits the object of study, our exchange

saw our perspectives converge, but also deviate, sometimes clash and ultimately

interweave.

This is why we decided to preserve a dialogic approach to introduce the questions provocatively posed by the title of this special issue, and the answers given

by our authors. The six essays, which we had the privilege of selecting from

among an impressive number of exciting proposals, offer a good survey of the

current state of the debate. We want to present this special issue as an opportunity to expand the dialogue and include a variety of different perspectives on the

temporality of the ‘post-’ in post-media and post-cinema. We hope the reader

will ind our exchange as productive, engaging and poignant as we felt it was

when we prepared it.

Milan and Frankfurt, October 2016

Cinéma & Cie, vol. XVI, no. 26-27, Spring/Summer 2016

�Miriam De Rosa and Vinzenz Hediger

*

mdr: I should probably start by asking you what you think post-cinema is.

Instead, I will begin with a confession. I have been working on ‘post-cinema’

for a while now: much has been written on the topic, many, diverse voices have

contributed to set in motion what I genuinely feel is an extremely stimulating

debate.1 Yet, after all that has been said and written, I am still not quite sure what

post-cinema is.

Is the shift from cinema to post-cinema solely a question of what we might call

the ‘nature’ of the medium? Is it determined by its material support and, therefore, by the technological element? Is post-cinema a broader term that describes

the fact that — borrowing from Rodowick2 — the ilm has entered its ‘virtual

life’? Or again, is it about the aesthetic changes that we can observe in much

of the contemporary cinematography? Or maybe a combination of both? Not

to mention other vital aspects of cinema and their most recent transformations,

such as distribution, spectatorship, etc.

To be honest, I am not sure post-cinema is about ilm at all. In fact, I would

argue that cinema is not only about ilm either. Conversely, I suspect that the

ontological interpretation of post-cinema (to which I also adhered, at irst) is based upon a sense of permanence and immobility which I now think is inherently

extraneous to cinema. To some extent, Shane Denson’s essay which opens our

edited special issue implicitly addresses this point, in that the relection on the

speculative nature of post-cinema he proposes focuses solely on computational

images and elaborates on the material engagement of media in a ‘discorrelated’

present. As a phenomenological object, cinema of course needs ‘a body’ delimited by a tangible skin (be it the ilm strip, as in the beautiful pages written by

Laura U. Marks and somewhat echoed by the texts by Sabrina Negri and Rachel

Schaff included in this volume, or the threshold of the red velvet curtains we

have so often crossed to enter the movie-theater). 3 Yet the idea of cinema is not

1

Among the most recent and inluential works, please refer at least to Post-Cinema: Theorizing 21st

Century Film, ed. by Shane Denson and Julia Leyda (Falmer: Reframe Books, 2016); Félix Guattari, ‘Vers une ère post-média’, Terminal, 51 (1990), trans. into English as ‘Towards a Post-Media

Era’, in Provocative Alloys: A Post-media Anthology, ed. by Clemens Apprich and others (Lüneburg: Post-Media Lab; London: Mute Books, 2013), pp. 26–27; Rosalind Krauss, ‘A Voyage on the

North Sea’. Art in the Age of the Post-Medium Condition (New York: Thames & Hudson, 1999);

Lev Manovich, ‘Post-Media Aesthetics’, <www.manovich.net/DOCS/Post_media_aesthetics1.

doc> [accessed 20 October 2016]; Chris McCrea, ‘Explosive, Expulsive, Extraordinary: The Excess of Animated Bodies’, Animation, 3.1 (2008), 9–24; Steve Shaviro, Post Cinematic Affect (New

York: Zero Books, 2010); Peter Weibel, ‘Die Postmediale Kondition’, in Die Postmediale Kondition, ed. by Elisabeth Fiedler, Elisabeth Fiedler, Christa Steinle and Peter Weibel (Neue Galerie

Graz am Landesmuseum Joanneum: Graz, 2005), pp. 6-13, trans. into English as ‘The Post-Media

Condition’, Postmedia Condition (Madrid: Centro Cultural Conde Duque, 2006). <http://www.

medialabmadrid.org/medialab/medialab.php?l=0&a=a&i=329> [accessed 20 October 2016].

2

D. N. Rodowick, The Virtual Life of Film (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007).

3

Laura U. Marks, The Skin of the Film: Intercultural Cinema, Embodiment, and the Senses (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2000); on the red velvet curtains delimiting the movie-

10

�Post-what? Post-when?

about permanence and immobility. It is a powerful repository of memory and an

archive of the past, but it is in that which enlivens memory and the past, in that

which keeps memory and past alive, moving, and vivid, which I think cinema

resides.

I am extremely simplifying but, to summarize, I believe many contemporary

cinematic forms do not provide us with anything but the constant evidence that

cinema is something variable, (positively) precarious, and changeable. Precisely

such mutability is what I feel inclined to identify as cinema — moving images

and, therefore, essentially, motion.

I think that the notion of the apparatus can serve to illustrate this point: looking more carefully at the theory of the apparatus, it seems to me that this

concept covers a number of recurring elements, which contributed to its institutionalization over the years, but a great deal of elements is not ixed at all.

vh: To take up your point about the mutability and even the malleability of cinema, we could approach the post-cinema debate from a history of science point

of view and take a page from Bruno Latour, arguing that cinema has, in a way,

never been modern. By this, I mean that cinema has never been a medium with

a consolidated speciicity, but rather a medium in permanent transformation. In

that sense, the cinema which now appears to be over, in the wake of which the

sufix ‘post-’ positions us, should only be considered a snapshot of a particular

moment in that permanent transformation.

In his book, Nous n’avons jamais été modernes,4 irst published in 1991, Latour

argues that most of the concepts and conceptual distinctions of modern scientiic

practice, most notably the distinction between ‘nature’ and ‘society’, are a lot

less stable than we assume. Making these concepts operable requires a constant

effort of articulation through material practices and institutional frameworks.

We can argue that this analysis also pertains to aesthetics. In the realm of aesthetics, one of the quintessentially modern concepts is, indeed, the concept of

medium speciicity. It can be traced back to Lessing’s 1766 essay Laokoon,5 in

which the author proposes that the arts may be distinguished from each other

by the material and structural properties of their medium of expression. This

is a stance that Lessing takes against Horace’s dictum ‘ut picture poesis’, i.e. the

notion, inherited from antiquity, that the arts can mutually express each other,

independently of their medium. Lessing’s essay belongs to a broader moment in

modern thought, the emergence of aesthetics as a sub-ield of philosophy. It appears a few years after Baumgarten’s Aesthetica and Burke’s essay on the sublime

theater and the sense of magic unfolding once crossed, the fascinating account by Antonello Gerbi

as reported by the equally vivid prose by Francesco Casetti in The Lumière Galaxy: Seven Keywords for the Cinema to Come (New York: Columbia University Press, 2015) comes to mind.

4

Bruno Latour, Nous n’avons jamais été modernes (Paris: La Découverte, 1991).

5

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Laokoon. Oder: Über die Grenzen der Malerei und Poesie (Stuttgart:

Reclam, 1994 [1766]).

11

�Miriam De Rosa and Vinzenz Hediger

and the beautiful.6 Very broadly speaking, all three are concerned with aesthetic value judgments, but while Baumgarten and Burke focus on questions

of logic and the logical form of value judgments, Lessing focuses on material

properties and the medium. If we fast-forward to the Twentieth century,

we find that art historians and art critics such as Clement Greenberg and

Michael Fried, but also film theorists like Siegfried Kracauer, still operate

within a Lessing-style framework. Whether a specific work has aesthetic

value continues to depend on how well it accords with the properties of the

medium.

mdr: The lineage connecting Lessing to Greenberg, Kracauer and Fried is quite

obvious. The correlation between aesthetic value and properties of the medium selected to express it reminds me of Arthur Danto’s critique of aesthetics. Rather than as

a branch of philosophy, Danto contends that aesthetics is in fact a philosophy of art.7

The ‘aesthetic’ value is for him to be understood as the result of a number of relational

properties of the work of art. It is in this frame — and this is why we could well call

them ‘relational’ properties — that he includes the essential connection among meaning, process of interpretation and underlying intention of the author. I ind an echo of

Danto’s argument in the text by Malcom Turvey and Ted Nannicelli included in this

special issue. This might sound like a detour, but is in fact of crucial importance because it takes us back to the ut pictura poiesis-debate that you mentioned above. If we

return to the sources, I believe we could consider Horatio as an epitome of a relational

conception of art — better yet, of the arts. This conception turns on the dichotomy

speciic/general, and I think that it implicitly permeates the relections by some of the

authors you named. Rosalind Krauss and her famous reference to Marcel Broodthaers’

‘in(e) arts’ claim in her opening of ‘A Voyage on the North Sea’ is a case in point.8

Krauss’ argument plays with the idea of ine arts as several different media, each with its

own speciicity, and their end (in), which in a way only defers the problem. Jean-Luc

Nancy found a wonderful way to synthesize this, which in my opinion is closer to solve

the problem, when he proposed the idea of ‘être singulier pluriel’.9 According to Nancy,

arts are as a matter of fact separated but would stem from a unique essence which

found diverse modes of expression over time, thus determining the emergence of

6

Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten, Aesthetica, repr. as Ästhetik (Meiner: Hamburg, 2007 [1750]);

Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015 [1757]).

7

Arthur Danto, The Trasiguration of the Commonplace: A Philosophy of Art (Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press, 1981). In the same vein, the perspective adopted by analytical philosophy may provide an interesting frame to look differently at issue of medium speciicity. It refuses to

conceive modernity and the postmodern as separated eras, each of which characterized by speciic

arts and interpretive modes, in favor of a more consistent — albeit luid — historical continuity

along which various particularisms would characterize various historical moments. Consequently,

this view seems to offer some suggestions to tackle the question of temporality at the heart of our

inquiry.

8

Krauss, ‘A Voyage on the North Sea’.

9

Jean-Luc Nancy, Being Singular Plural (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2000).

12

�Post-what? Post-when?

speciic yet complementary arts. Therefore, the end of a certain art would stand,

in fact, for the beginning of its own plurality.10 In this view, cinema would be one

among multiple languages (arts), having its own ‘speciicity’ but at the same time

sharing a common root with others and, consequently, it would not be a monolithic, autotelic and, so to say, ‘closed’ medium, but would rather be in constant

connection with other media.

vh: Well, things are not quite as harmonious for Kracauer, for instance. For him,

the speciicity of ilm needs to be thought independently and in contrast to the

other arts. Thus, any piece of a newsreel is ilmic, because it redeems physical reality, while a ilmed adaptation of a Shakespeare play is not ilmic, because it stresses

the formgebende tendenz, the intervention of the artist, over the properties of the

photochemical reproduction of ilm. It is treading in those same footsteps, that

Rosalind Krauss introduces the concept of post-medium, when she is confronted

with works that are indisputably art works like those by Broodthaers, but no longer conform to the criterion of medium speciicity. Now my claim would be that,

even after Kracauer, whose Theory of Film is the last, great explicitly Lessingian

attempt to get to the heart of cinema in the history of ilm theory, ilm studies and

ilm theory, whether explicitly or not, took a page from art criticism and art theory

when they deined their object. The challenge in the 1960s and 1970s was to delineate cinema as an epistemic object that was solid and consistent enough that it

could legitimize an entire academic ield devoted to its study. Now it’s important

to add a caution, in order not to overly homogenize ilm studies as a discipline.

Film Studies irst emerged as an interdisciplinary ield in post-war Europe in the

shape of the ilmology movement, but it only became a discipline in the 1970s,

in the US, Germany and Britain largely by branching out from literature departments. To the extent that Film Studies has a certain coherence as a ield, one

could argue that the outlines of academic ilm theory were formulated in Paris in

the 1960s and 1970s. Their teachings were exported to other countries through

a generation of ilm scholars who made a passage through Paris, to study with

such scholars as Metz and Bellour, from Constance Penley and Janet Bergstrom

to David N. Rodowick, Francesco Casetti and many others.

Now this is where the apparatus comes into play, and where it becomes important that, as you say, the apparatus is far from a ixed entity…

mdr: And that ‘cinema’ does not only just equal ‘apparatus’…

vh: Exactly. I would argue that to the extent that ilm studies as a ield gave a

coherent answer to the challenge of delineating their object of study, it could be

summarized by a formula comprised of the triad of ‘canon + index + apparatus/

dispositif’. ‘Cinema’ was, irst, a catalogue of canonical works, roughly the canon

10

Jean-Luc Nancy, The Muses (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1997).

13

�Miriam De Rosa and Vinzenz Hediger

of auteur cinema; ‘cinema’ was, second, a photographic medium whose core material property was photomechanical reproduction, or, to phrase it in the terms

of Peircean semiotics, a medium based on ‘indexicality’; and ‘cinema’ was, third,

a dispositif (or, to put it in more properly Althusserian terms, an apparatus), an

aggregation of a public space, a technology of projection, and the social habit of

movie-going and the mental framework of spectatorship. As it turned out, the

triad of canon, index and dispositif that deined ‘cinema’ as an object of study

proved to be prone to accidents and episodes of instability. The transition to

digital photography in the 1990s threw the index in crisis, the development of digital networks and platforms ended the privilege of the dispositif of cinema over

other modes of circulation, and new modes of digital access and the discovery of

new ields of research such as ephemeral and orphan ilms subverted the canon.

One way of dealing with this triple crisis is to declare, once again, the death

of cinema and adopt an attitude of protracted mourning. Krauss actually makes

a similar point with regards to the visual arts: the obsolescence of the medium

coincides with the highest point of its maturity; the ‘post-medium condition’ is

to be addressed in the mode of an elegy. In our issue, in addition to the essay by

Ted Nanincelli and Malcom Turvey a review of a new book by André Gaudreault and Philippe Marion discusses these attitudes in a critical perspective. But

another way of dealing with the triple crisis of canon, index and dispositif is to

argue, quite to the contrary, that cinema has never been modern: that the search

for a media speciicity of cinema is futile and misses the point, because cinema

is an unspeciic medium, a medium of constantly changing and often transitory

conigurations, of which ‘cinema’ was only one.

mdr: If there is, indeed, no speciicity to lose, but only a succession of transitory conigurations, the question in our title — post what? post when? — acquires

a new, and somewhat polemical, meaning.

vh: Yes, there is a stance in there somewhere that could be paraphrased as

‘enough already with the post-talk; can we move on, please?’ I think it’s a good

question to ask, particularly in a situation where we are at risk of making our

lives in the long shadow of a traumatic experience of loss permanent. To argue

that cinema has ever been modern seems like a good cure for the melancholia of

a modernism, which has just ended forever.

mdr: One might add that not only cinema has never been modern, but Film

Studies have always been a permeable ield of inquiry, one — as you maintain —

with an internal coherence but with an openness to other ields of inquiry, shifting

between discipline and ield, as Roger Odin recently reminded us.11

11

Roger Odin, ‘A propos de la mise en place de l’enseignement du cinema en France. Retour sur

une experience’, in Il cinema si impara? Sapere, formazione, professioni / Can we Learn Cinema?

Knowledge, Training, the Profession, ed. by Anna Bertolli, Andrea Mariani and Martina Panelli

14

�Post-what? Post-when?

Furthermore, I think the suggestion you used is very much in line with what I

was trying to touch upon earlier: cinema is luid, and there are moments throughout history which correspond to major or minor luctuations, that is, major or

minor variations in terms of established objects and basic notions such as the ilm,

the apparatus, etiquette and patterns of spectatorship, etc. When the ‘luctuation’

is minor, then a solidifying impulse crystallizes a number of forms into canons,

behaviors into habits and, eventually, rituals. When variation prevails, then certain aspects of the medium are reconigured and the objects, as well as the critical

and scientiic approaches studying them, also undergo a process of transformation.

To push the metaphor further — we could perhaps describe these dynamics in

terms of solidiication, liquefaction and sublimation: through recurrence, certain

aspects of the cinematic experience turn into stable elements; they gain consistence

and, therefore are (temporarily) solidiied. Conversely, whilst certain traits raise

and come to the surface others lose their consistency and are somehow diluted,

watered down, as if liqueied throughout the folds of time and replaced by new

practices. Such a perspective ultimately describes a modulation, for I assume the

changes affecting the moving image over time we are alluding to are the results of

complex processes produced by a number of interwoven factors.

There is one further dynamics that may complement the two I just named and

which complete my ‘alchemic’ reading, namely sublimation. When the changes

are conspicuous, we could well visualize ‘major luctuations’ introducing a prominent alteration of the ‘liquid cinematic atmosphere’ I tried to describe here

— sublimation would then indicate a more radical metamorphosis, that is, a

passage that is a faster or more evident transition from one coniguration to another, resembling a profound modiication of an established ilmic form, its parameters and surrounding critical discourses. Experimental projects such as Tony

Oursler’s environmental projections are a good example and a quite thoughtprovoking metaphor of this (ig. 1).

These mechanisms do not exclude each other. Rather, they co-exist and emerge with a varying strength throughout time, readjusting the new balance at every

turn. As in a sort of cycle, certain aspects emerge and establish themselves as a

standard, whereas others are surpassed and therefore progressively abandoned,

either proposing what may be an original nuance, just a slim novelty or rather

determining a real shift and a consistent change. Such a logic rests upon a conception of continuity, which, as Bolter and Grusin pointed out,12 would feature

the moving image as part of a broader media environment. Besides remediation,

which I am not sure is a concept we really need to employ here, this reminds me

some beautiful pages by Italo Calvino, as he compared Ovid’s linguistic structure

to that of cinema. I would argue his remarks offer an eloquent and valuable relection to observe contemporary (audio-visual) media on the whole:

(Udine: Forum, 2012), pp. 93–101.

12

Jay D. Bolter and Richard Grusin, Remediation: Understanding New Media (Cambridge, MA and

London: MIT Press, 1999).

15

�Miriam De Rosa and Vinzenz Hediger

everything has to follow apace, […] every image must overlap another, emerge […].

It is the principle of cinema: each frame, as each verse, must be full of moving visual

stimuli. [...] A law of maximum economy dominates this poem [according to which]

new forms draw as much as possible from the old ones.13

Not by chance, Calvino is commenting on Ovid’s Metamorphoses. I cannot but

see a similarity between his acute observations on the rough material composing

the poem, and the moving image as a rough material of sorts which is to be found

in a number of diverse contemporary cinematic forms: as the former represents

an ensemble of possible stories synthesizing the ‘living multiplicity’14 typical of

myth, so the latter is the basic malleable material that can well be shaped into

a number of different fashions giving birth to diverse cinematic forms. The scenario where this complex and constant process takes place is a moving territory

crossed by clashing and convergent tensions at once,15 occurring in a transition

phase. The post-media age is one of these transformation moments in which a

“metamorphosis”, an important reconiguration of both cinema as an object and

the critical discourse about it takes place. The reconceptualization of a number

of moving image practices including those connected to archive, exhibition and

preservation to which the volume edited by Giovanna Fossati and Annie van

den Oever reviewed in this issue is devoted, is emblematic to this extent (ig. 2).

vh: I prefer the notion of ‘living multiplicity’ to that of ‘remediation’. ‘Living

multiplicity’ revives the long tradition of biological metaphors that address

cinema as a living organism rather than technical tool or just another art

form. This tradition stretches from early ilm theory and its borrowings from

Lebensphilosophie and Bergson — a connection thoroughly studied by Inga

Pollmann in a forthcoming book and, similarly, by Chris Tedjasukmana in a

book published last year — to Bazin and the life cycle metaphors of genre

theory and on to Vivian Sobchack’s concept of ilm viewing as an encounter

and interaction with the ilm’s lived body.16 Life metaphors deserve a critique

13

Italo Calvino, ‘Gli indistinti conini’, in Metamorfosi, Publio Ovidio Nasone (Torino: Einaudi,

1987), pp. XII–XIII (my translation).

14

Ivi, p. X.

15

Implicitly sitting upon the idea of the ‘art after the art’, thus recalling a similar rhetoric we are

analyzing as regards to cinema, Nicholas Bourriaud also questioned the future of art looking at a

number of dynamics which led him to identify an object that he terms ‘exform’. Albeit articulating

a different theoretical framework based on a different set of labels, he seems nonetheless to identify

the necessity to address the mechanisms deining the artistic discourse and its objects proposing a

conceptual category which encapsulates the same aesthetical sensitivity we are trying to elaborate

on. See Nicholas Bourriaud, The Exform (London, New York: Verso, 2016).

16

Henri Bergson, Creative Evolution (New York: Sheba Blake, 2015 [1907]); Inga Pollmann,

Cinematic Vitalism: Film, Theory, and the Question of Life (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University

Press, forthcoming); Chris Tedjasukmana, Mechanische Verlebendigung. Eine Theorie der

Kinoerfahrung (München: Fink, 2014); André Bazin, What Is Cinema? ed. by Hugh Gray, 2

vols (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967); Vivian Sobchack, The Address of the Eye: a

Phenomenology of Film Experience (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992).

16

�Post-what? Post-when?

in their own right, but I think that ‘living multiplicity’ opens up a rich set of

possibilities. My problem with ‘remediation’ is the same as my problem with the

concept of ‘intermediality’: both reify the medium as an ontological unit and

turn it into an underlying substance, to which the processes of remediation and

intermediality relate as accidents. This creates what is in my view a completely

unnecessary problem of discovery: irst we must ind, delineate and describe

the medium, and then we can move on to an analysis of whatever it is that we

describe as ‘remediation’ and ‘intermediality’. I believe we should try to avoid

this ‘substantiality trap’, and I think that the concept of reconiguration can

help us here. In your study about postmedia, you worked on the relationship

between the relocated moving image and space — you termed it ‘space-image’

— and proposed to deine it as a ‘coniguration of experience:’17 if we agree

that cinema is indeed a shape-shifting object of study, we can expand on your

insight and use the term ‘coniguration’ to apprehend cinema in its varying

shapes, both as they develop over time and as they co-exist and interact with

each other.

mdr: I think we agree on ‘living multiplicity’. Also, I do agree with the idea of

reading post-cinema in relation to a wider context and — as I argued elsewhere18

— of putting other conigurations of the moving image on equal footing with

‘cinema’. Your historical take is very convincing, too; perhaps I wouldn’t sketch

the phases — the three successive crises of the index, the dispositif and the canon

— that you brought up earlier in such a linear way, though: on the one hand

there is indeed a chronological development, especially in terms of the agenda of

Film Studies as a discipline, but on the other hand I believe the three focuses you

identiied do not simply make room one to the other — they somehow continue

being co-present, albeit with a different centrality in the frame of the theoretical

discourses which progressively took shape around cinema.

vh: One of the advantages of the concept of coniguration to me seems indeed

to be that it allows us to move on from modernist melancholia, and embark upon

a variety of avenues to more or less completely rewrite the history of cinema.

mdr: Which would then mean that conigurations may well emerge out of a

disruption of the institutional and established way of conceiving history. In other

words, I’d rather go for a non-linear coniguration of such discourses, one which

Miriam De Rosa, Cinema e postmedia. I territori del ilmico nel contemporaneo (Milano: postmedia books, 2013), p. 66.

18

I had the chance to approach this issue as regards to artistic moving images during my research

stay at Goethe University in Frankfurt, where this dialogue started taking shape more consistently.

The irst result of that strand of my research is published as Miriam De Rosa, ‘From a Voyage to

the North Sea to a Passage to the North-West. Journeys Across the Contaminated Histories of Art

and Film’, in A History of Cinema without Names, ed. by Diego Cavallotti, Federico Giordano and

Leonardo Quaresima (Milano and Udine: Mimesis International, 2016), pp. 149–55.

17

17

�Miriam De Rosa and Vinzenz Hediger

would enable to acknowledge the inherent complexity of our object of study.

I would suggest to adopt complex theory as a lens through which looking at

cinema and post-cinema. This would quite it with the concept of coniguration

as a key-term to understand moving images and their pattern of entanglements

(rather than evolution) in the post-media age. The essays by Saige Walton and

Monica Dall’Asta included in this collection might be seen as important contributions to a similar framework, notwithstanding the fact that they do not aim

at proposing a new reading of post-cinema per se. Moreover, your account of

Agnès Varda’s photographic work, particularly her work on Cuba, which you review in this issue of the journal, conirms that moving images are part of a wider

visual culture and that its components are dynamic forms19 — conigurations, as

we are claiming — continuously inluencing each other.

vh: However, I do think that the concept of coniguration offers an opportunity

to re-frame the post-cinema debate. Let’s get speciic. In terms of unraveling the

complexity of conigurations of the moving image, we could distinguish between

several levels of analysis: we could ask what it is that a given coniguration of

moving images does, i.e. we can discuss a coniguration in terms of its operative

aspect — which can be to provide an aesthetic experience, as in the classical

dispositif of the cinema, or to produce knowledge, as in laboratory and scientiic

uses of ilm; we can study the ways in which the moving image relates to other

elements of its coniguration — for instance, to paratexts in the case of commercial

cinema, or to writing and other modes of notation in ilm-based research such

as visual anthropology, for instance; and we can study the spatial dimension of a

given coniguration, precisely what you called ‘space-image’. We can distinguish

between these levels for the purposes of analysis, while still keeping in mind that

the operational, relational and situational aspects are intertwined. But what such

an analysis could help us to achieve is to subvert the primacy of the object of

‘cinema’ by aligning it, on equal footing, with a multitude of other conigurations

of the moving image. This would also help us understand that what remains of

cinema (to quote the title of a recent book by Jacques Aumont)20 requires no

mourning, but merely our sustained curiosity and attentiveness.

19

The concept of ‘dynamic forms’ as key-notion to understand cinema as a language encapsulating

an essential sense motion is at the heart of an on-going research project devoted to artistic moving

images I am developing in association with Catherine Fowler. Its irst output has been presented

as a joint conference paper ‘Contaminated Histories of Art and Film: Thinking Topologically’, at

FilmForum XXIII International Film Studies Conference, Gorizia, Italy, 9 - 15 March 2016.

20

Jacques Aumont, Que reste-t-il du cinema? (Paris: Vrin, 2012).

18

�Post-what? Post-when?

Tony Oursler

The Inluence Machine, 2000

Video and sound

10/19/2000 – 10/31/1000

Photo by: Aaron Diskin

Courtesy of Public Art Fund, NY

19

�Miriam De Rosa and Vinzenz Hediger

Tony Oursler

The Inluence Machine, 2000

Video and sound

10/19/2000 – 10/31/1000

Photo by: Aaron Diskin

Courtesy of Public Art Fund, NY

20

�Speculation, Transition, and the Passing of Post-cinema

Shane Denson, Stanford University

Abstract

What comes after post-cinema? Such a question calls for speculation as a

central mode of inquiry. However, this speculative turn is engaged not only by

the question of what comes after the ‘post’; for post-cinema, at its best, is itself

already a speculative term — despite the fact that it grows, historically, out of

theories of loss (the loss of the index, the end of celluloid, the demise of cinema

as an institution). Against this backdrop of mourning and melancholia, postcinema is speculative in at least two senses. First, the concept of post-cinema

is future-oriented at root, as it purports to gain purchase on movements along

an uninished trajectory, hence speculating of necessity about its own future

course as a determinant of present actuality. Second, post-cinema refers to media

engaged materially in a speculative probing of the present. The ‘presence’ of

experience is now more radically than ever — because materially, medially —

dispersed, not just as a play of signiiers but across and within an ecology that is

materially redeining the parameters for life and agency itself in post-cinematic

times. Accordingly, the question of post-cinema’s passing is the question of

time’s passing in the space of post-perceptual mediation.

What comes after post-cinema? This question — a pressing one today both

for theorists of ‘new’ media and for those who have identiied with the putatively

‘old’ concerns of cinema studies and ilm theory — demands speculation as a

central mode of inquiry.1 Meanwhile, however, the notion of speculation is overdetermined; it might evoke associations with speculative realism (recent philosophical tendencies such as ‘object-oriented ontology’), speculative philosophy (an

older philosophical impulse exempliied in the work of Alfred North Whitehead), speculative inance (along with the algorithmic processes that have accele-

1

On the speculative nature of post-cinematic theory, see Shane Denson, Steven Shaviro, Patricia

Pisters, Adrian Ivakhiv and Mark B. N. Hansen, ‘Post-Cinema and/as Speculative Media Theory’,

panel at the 2015 conference of the Society for Cinema and Media Studies, Montréal, Canada, 27

March 2015; video of the complete panel is available online: <https://medieninitiative.wordpress.

com/2015/05/24/post-cinema-panel-complete-videos/> [accessed 18 October 2016].

Cinéma & Cie, vol. XVI, no. 26-27, Spring/Summer 2016

�Shane Denson

rated such speculation and made capital not only ‘inhuman’ in its consequences

but a somewhat nonhuman affair as well), or speculative media (an as-yet underdeined notion that might draw on any or all of the above in order to think about

the predictive, future-oriented trajectory that differentiates contemporary media

from the ‘memorial’ functions of phonography, photography, and cinema). However, the speculative turn suggested by this non-exhaustive list is engaged not

only by the question of what comes after the ‘post’; for post-cinema, at its best,

is itself already a speculative term — despite the fact that it grows, historically,

out of theories of loss: the loss of the index, the end of celluloid, the demise of

cinema as an institution.2 Against a backdrop of mourning and/or melancholia,

both the notion and the (suspected or only speculated) referent of ‘post-cinema’

are speculative in at least two senses, which I aim to articulate in this essay and to

put into conversation with a range of ilm- and media-philosophical relections

on the fate and future of moving-image media.

First, I hope to show that the concept of post-cinema is future-oriented at

root, as it purports to gain purchase on movements along an uninished trajectory, hence speculating of necessity about its own future course as a determinant of

present actuality. But though such might be said of any historical development,

since life is never lived in a punctual ‘now’ but always in a thick present that is

rich with protentional and retentional traces, there is nevertheless something

special about the becoming of post-cinema. This is due to what I have elsewhere

termed the ‘discorrelation’ of subjective experience and material substrate that,

in a culmination or radicalization of media-historical impulses going back at least

to the telegraph, comes to impinge directly upon moving images in post-cinema.3

In contrast to cinema’s photographic images, post-cinema’s computational images are generated in a microtemporal interval that is inaccessible to the macrotemporally constituted self of subjective perception. Thus, the temporal window

of experience itself becomes the object of the minutest calculation, ‘premediation’,4 or algorithmic pre-processing at a microtemporal level. Time in the postcinematic era passes faster, it would appear, though precisely appearance or the

realm of the phenomenal (and speciically, that of the image) is called radically

into question in the post-perceptual space of discorrelated images.5

2

For a nuanced theoretical account, see D. N. Rodowick, The Virtual Life of Film (Cambridge,

MA: Harvard University Press, 2007). For a somewhat skeptical historicizing approach, see André

Gaudreault and Phillipe Marion, The End of Cinema? A Medium in Crisis in the Digital Age, trans.

by Timothy Barnard (New York: Columbia University Press, 2015).

3

Shane Denson, ‘Crazy Cameras, Discorrelated Images, and the Post-Perceptual Mediation of

Post-Cinematic Affect’, in Post-Cinema: Theorizing 21st-Century Film, ed. by Shane Denson and Julia Leyda (Falmer: REFRAME Books, 2016) <http://reframe.sussex.ac.uk/post-cinema/2-5-denson/> [accessed 18 October 2016].

4

Richard Grusin, Premediation: Affect and Mediality after 9/11 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan,

2010).

5

Mark B. N. Hansen, ‘Algorithmic Sensibility: Relections on the Post-Perceptual Image’, in PostCinema, ed. by Denson and Leyda <http://reframe.sussex.ac.uk/post-cinema/6-3-hansen/> [accessed 18 October 2016].

22

�Speculation, Transition, and the Passing of Post-cinema

This brings us to the second meaning of speculation, then: post-cinema is

not just a future-oriented concept, but it refers to media engaged materially in

a speculative probing of the present. The ‘presence’ of experience is now more

radically than ever — because materially, medially — dispersed, not just through a deconstructive play of signiiers but by way of multi-leveled, networked

processing operations taking place across and within an ecology that is materially redeining the parameters for life and agency itself in post-cinematic

times.6 If post-cinema means discorrelation, however, and this discorrelation

brings with it a transformation of time that necessitates a speculative relation to

appearance (because the objects of perception, e.g. images, are generated in a

time called ‘real time’ but which is categorically outside our real-time subjective

perception), then the concept of post-cinema must inally be seen as a transitional concept in a strong sense. For the ‘post’ does not mark so much an end

(as in earlier discourses of the end of cinema) but rather has its heuristic value

by virtue of marking a difference that may very well stop making a difference:

as the perceptual technology of cinema is absorbed, resituated, or ‘relocated’7

within the post-perceptual ecology of twenty-irst-century media, this metabolizing movement implies that the difference ‘cinema/post-cinema’ itself might

become not only imperceptible but also ultimately ineffectual. Post-cinema, as

a construct, is necessarily transitional: it will pass. When we recognize this basic

transitionality, however, then we see that the question of post-cinema is already

the question of what comes after post-cinema — and, more fundamentally, that

the question of post-cinema’s passing is the question of time’s passing in the space

of post-perceptual mediation.

Transitional Media

What I have just said of post-cinema might, with some justiication, be said of

cinema as well: the question of cinema is the question of what comes after cinema. Bazin’s great question ‘what is cinema?’ gives way to speculation on tendencies and trajectories that point beyond — towards speculation, in Bazin’s case,

on what he called ‘the myth of total cinema’.8 This notion of totalization carries

within itself the idea of a situation in which the cinema/not-cinema distinction

begins to break down, or in which the phenomenal differences that distinguish

the cinema from its environment become imperceptible. Thus, for Bazin, the

question of cinema’s nature gives way to relection on a kind of nature that per6

On this redeinition of the experiential environment, see Mark B. N. Hansen, Feed-Forward: On

the Future of 21st-Century Media (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015).

7

‘Relocation’ is one of the ‘key words’ put forward as a deining characteristic of twenty-irstcentury cinema in Francesco Casetti, The Lumière Galaxy: Seven Key Words for the Cinema to

Come (New York: Columbia University Press, 2015).

8

André Bazin, ‘The Myth of Total Cinema’, in What is Cinema? trans. by Hugh Gray, 2 vols

(Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1967), I, pp. 17–22.

23

�Shane Denson

sists after cinema has perfected its ‘total and complete representation of reality’9

and hence become indistinguishable from it. Can we say, then, that the idea of

cinema itself already leads inevitably to the idea of post-cinema?

It would perhaps be hasty to afirm this suggestion, and it is anyway complicated for Bazin by his insistence that ‘cinema has not yet been invented!’10 But

the anachronism and the paradox of the Bazinian idea — according to which the

mythical ideal of cinema precedes its technical implementation, but where the

full realization of the cinema (its ‘invention’ in a strong sense) would also imply

its end (in the sense that it would no longer make sense to distinguish cinema

from nature or reality more generally) — might in fact shed light on what I am

calling the transitionality of post-cinema.

Consider, in this connection, the strangely incompatible set of deinitions that

Wiktionary, the collaborative dictionary companion to Wikipedia, offers for the

term ‘postcinematic’.11 On the one hand, the adjective is said to mean ‘after the

decline of cinema’; on the other hand, however, and far more surprisingly, it

is also deined as ‘after the invention of cinema’. But if this latter deinition is

surprising, it is not for all that illogical: while terms like postmortem and posthumous imply that something happens after the conclusion of something else

(when life is over, for example), other uses of ‘post-’ imply only that something

happens after the advent or occurrence of something (for example, post-Kantian

philosophy refers to philosophy conducted in the wake of Kant’s inluence; it

commences not with Kant’s death but with the publication and reception of the

Critiques). Seen thus, these are two completely distinct meanings of the term

‘postcinematic’ — implying, by extension, two distinct notions of post-cinema:

either the post-cinematic era commenced in 1895 or thereabouts, with the invention and public exhibition of the Cinématographe, or it commenced much more

recently, for example with the demise of celluloid and photographic indexicality,

or by virtue of some other hypothesized decline (e.g. a waning of the collective

audience, the eclipse of the big screen by a plethora of little ones, or the decline

or downfall of some set of properly cinematic values). One of these meanings is

therefore predicated on the birth of cinema, while the other is predicated on its

death.

Accordingly, the two meanings on offer here are clearly contradictory with

respect to one another, but perhaps there is some truth to be found in the contradiction. Again, I am interested in thinking about post-cinema as an essentially

speculative notion, not so much as a state attained deinitively in connection with

some determinate event, and certainly not one that would be deined in terms of

an absolute historical break, but more perhaps as one of the inherent questions

of cinema. Taken together, the two deinitions might nudge us towards this spe-

9

Ivi, p. 20.

Ivi, p. 21.

11

‘Postcinematic’, in Wiktionary: The Free Dictionary <https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/postcinematic> [accessed 18 October 2016].

10

24

�Speculation, Transition, and the Passing of Post-cinema

culative and transitional understanding: by focusing alternately on cinema’s birth

and its death, i.e. on the beginning or end of its ‘life’, they suggest signiicantly

that post-cinema is central to the cinema’s very existence, to its being or becoming. Nevertheless, the two deinitions are hardly saying the same thing; with

respect to periodization, as we have seen, it makes a huge difference whether we

deine post-cinema in relation to cinema’s birth (let us call this deinition 1) or

in relation to cinema’s death (deinition 2). However, we might pair deinition

1 with Gaudreault and Marion’s observation that cinema has died at least eight

‘deaths’ in the course of its life, the irst being pronounced right at the moment of

its birth — by none other than the father of the Brothers Lumière, who said that

‘Cinema is an invention with no future’.12 In this sense, all of cinema has been

post-cinema not just in the sense of coming after the advent of moving images

but in the more common meaning of after cinema (i.e. ‘after’ in the sense of following its demise). Deinition 1 and deinition 2 therefore merge or converge in

this unorthodox historiography of cinema.

But things get even more complex when we take into account Gaudreault and

Marion’s notion of the ‘double birth’ of cinema.13 On this account, cinema was

born irst as an apparatus (ca. 1895) and then as an institution (in the 1910s). It

is this second birth that, for Gaudreault and Marion, is the authentic birth of

cinema. Thus, cinema’s irst death comes before its actual birth, and the advent

of post-cinema is therefore rendered, paradoxically, a pre-cinematic reality. This

view might be seen as a sort of distant cousin of Bazin’s notion that the cinema

is itself a speculative ideal that has not yet been invented; in Gaudreault and

Marion’s alternative, cinema’s death is likewise a speculative ideal that precedes

the cinema’s invention. Taken literally, this would imply a reductio ad absurdum

of deinition 2 (according to which post-cinema is ‘after the decline of cinema’);

for what is after the decline can hardly come before the advent, except in some

metaphorical or conceptual sense (for example, as an inherent trajectory or conceptual inevitability, the way that death might be said to be inseparable from life

in general and therefore precedes any actual or individual birth). But though it

would be wrong to take Gaudreault and Marion’s suggestion in an overly literal

sense (indeed, their point is to cast doubt on the notion of cinema’s ‘death’ in

the irst place), their history of cinema’s multiple births and deaths might help

us to see post-cinema neither in terms of everything that follows the invention

of cinema (deinition 1, a ‘nominal’ and relatively uninteresting deinition) nor

as something that follows the demise of cinema (deinition 2, the more common

but ‘vulgar’ deinition) but as a potential or speculative possibility inherent in

cinema itself.

What can we say, then, to lesh out an alternate deinition of post-cinema — a

‘deinition 3’, so to speak? First of all, the lesson to be learned from these paradoxes of births and deaths, beginnings and ends, would seem to be that life

12

13

Gaudreault and Marion, p. 26.

Ivi, pp. 31–35.

25

�Shane Denson

happens in the middle; we should accordingly shift our focus away from the limit

cases and think about cinema and post-cinema in the course of their becoming,

as they exist in transit. We need to look at things in medias res. There is a temptation among critics to mark the limits, to deine a period or constellation as a

closed unit, but this fails to capture the reality of being-in-the-middle, of inding

oneself somewhere along an uninished trajectory (which is the only place one

can really ind oneself), trying to intuit what that trajectory might be, where it

started and where it might lead. We should be guided by this in our attempts to

describe post-cinema, which is nothing if not a moment of radically unresolved

change. Let us start, then, from the following question: how does it feel to be in

the middle of change?

In the Middle

We might take a cue from Steven Shaviro, who in his relections on ‘post-cinematic affect’14 refers to Raymond Williams’s notion of a ‘structure of feeling’.15 It

is worth returning to Williams’s explication of this concept, which is designed to

militate against dichotomies such as that between the ‘social’ and the ‘subjective’

— dichotomies which according to Williams attempt to account for the present

at the expense of reifying the past, i.e. through the ‘conversion of experience into

inished products’.16 There is something similar at work, I suggest, in reifying the

cinema as past in order to either celebrate or condemn our post-cinematic condition. This involves an exaggeration of the ixity of the object called ‘cinema’, a

denial of the inherent lux and openness of its borders. And this media-historical

impulse both draws upon and feeds back into a media-ontological fetishization

of ilm, especially pronounced with respect to the question of indexicality.

Without a doubt, the very real material connection between pro-ilmic reality

and its imprint on celluloid was capable of giving rise to those powerful and

uncanny experiences described so eloquently by Stanley Cavell17 and, more recently, David Rodowick:18 the continuity of recorded and projected image placed

viewers in the strange temporal situation of being ‘present’ at past events. And

this situation is, I think, directly relevant to an assessment of cinema’s particular

‘structure of feeling’, to the temporal quality of being-in-the-middle of a cinematic experience and, by extension, in the midst of a cinematic era. But it should be

emphasized that this description privileges one level of the overall reality, that of

subjective perceptual experience, at the expense of another, that of the microsco14

Steven Shaviro, Post-Cinematic Affect (Winchester: Zero Books, 2010).

Raymond Williams, ‘Structures of Feeling’, in Marxism and Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977), pp. 128–35.

16

Ivi, p. 128.

17

Stanley Cavell, The World Viewed: Relections on the Ontology of Film (New York: Viking Press,

1971).

18

Rodowick, The Virtual Life of Film.

15

26

�Speculation, Transition, and the Passing of Post-cinema

pic physical interactions between light, silver halide, and retinal rods and cones.

The latter level is of course outside the realm of normal phenomenal experience,

but it is not altogether different in this respect from the digital substrate of zeroes

and ones that is commonly held responsible for destroying the indexical relation

and, by some accounts at least, for destroying the cinema itself as an experience

and an era.

My point is not that nothing has changed, that there is no difference between

cinema and post-cinema; on the contrary, I think that the intercession of digital

processes changes things quite radically. But the difference is not to be located

solely in the interruption of analogical processes or experiences, for as I have

suggested already, those experiences were themselves undergirded by material

processes that are discontinuous with respect to integral or ‘molar’ experience.

On the other hand, though, it is true that the encoding of images is quite different from the apparently far more contingent capture of light in photochemical

processes, where the array of crystals forming the images is different not only

from frame to frame but also from print to print. Rodowick has highlighted this

contrast between code and crystalline contingency and argued that digital images lack the materiality, and the attendant entropy, of photographic images —

for digital information is capable of being copied exactly, and without loss, in

a way that photographic images are not.19 Accordingly, Rodowick suggests that

digital images, as informatic inscriptions, are no longer indexical but belong to

the symbolic register (in the categories of Charles Sanders Peirce’s semiotics).20

It seems wrong, however, to reduce (or inlate) digital information or data to

an exclusively symbolic register, because like the crystals of silver halide that give

photochemically based images their characteristic ‘grain’, digital information too

retains its materiality, even physicality. To begin with, digital images are not ‘really’ reduced to zeroes and ones in the irst place (as Rodowick says); that is indeed

a symbolic rendering of them, such that we can grasp them cognitively, but a

string of binary digits (such as ‘1111 0011 0010 1010’) is merely a representation

— as should be clear from the fact that it can be converted to a hexadecimal

value (‘F32A’) or decimal number (‘62250’). With respect to the algorithmic processes of encoding and decoding, zeroes and ones stand in as proxies for material

processes, for a much less binaristic lux of voltage differentials, the actualization

of which is never as neat and clean as any of these representations would suggest.

And in terms of storage, the code base is likewise subject to material processes of

entropy and decay, as Matthew Kirschenbaum has emphasized in his forensically

based ‘reading’ of hard drives.21 It is thus simply untrue that digital images are

immaterial entities, so rather than follow Rodowick in tracing a shift from the

indexical (associated with Peirce’s ontological category of Secondness) to the

19

Ivi, pp. 110–24.

Ivi, p. 120.

21

Matthew G. Kirschenbaum, Mechanisms: New Media and the Forensic Imagination (Cambridge,

MA: MIT Press, 2012).

20

27

�Shane Denson

symbolic (associated with Thirdness), we might instead follow Mark Hansen in

his suggestion that digital images in fact produce new Firstnesses.22 That is, far

from being immutably inscribed in an unchanging codebase, digital images are

imbricated in highly volatile and generative algorithmic processes that fail to reproduce ‘the same’ image over and over but in fact produce entirely new images

with each playback. Glitches and compression artifacts give us a glimpse of this

generative processuality and point us towards a new temporal quality of movingimage media and our experience of them.

I will turn in a moment to this new temporality, which I argue ushers in and

exempliies the new speculative quality of post-cinema. Before doing so, however, I want to emphasize what I take to be the signiicance of this discussion of

indexicality. In highlighting the microscopic processes at work in both cinematic

and post-cinematic media, I am trying to counter a certain fetishization of the index, which perpetuates unrealistic stories about the mechanisms both of cinema

and of digital computation alike. One conclusion to be drawn from this is that

we should not exaggerate the clarity and precision of the dividing line between

cinema and post-cinema. But this should not lead us to conclude that there is

simply no difference, or that the term post-cinema is gratuitous and serves only

to exaggerate the distinction in precisely this way. There are very real differences: material differences, as well as social, contextual, and perceptual ones. And

even if, as I suggested at the outset of this essay, these differences are destined to

fade (especially if ‘convergence’ is thought not in terms of a homogenization but

rather a multiplication of media forms, among which the cinema/post-cinema

distinction becomes less central or pronounced), the term post-cinema nevertheless serves an important heuristic function at present in not only highlighting these differences but pointing to their role in this multiplication of media-technical

capacities (or affects: the power to affect and to be affected). In short, the term

post-cinema serves to focus our attention on the transitional lux in which we

currently ind ourselves.

And the debate over indexicality and encoding, far from being beside the

point, is symptomatic of this transitional experience — part of what it feels like

to be in the midst of this change. Much of the debate has been conducted —

whether for celebratory or elegiac purposes — towards the goal of delineating

our medial past from our present. This goal, as I have suggested, is misguided

in its reifying impulse. But the positive upshot of the debate, as I see it, is that it

causes us to recognize that there are always microscopic or extra-perceptual processes happening right ‘in the middle’ of mediated perception: between subjective experience and the objective event or situation that is being presented to us.

This insight, I suggest, is essentially anti-reiicational with respect to subjective

experience, which it shows to be founded upon volatile pre-subjective processes

that are capable of unsettling the supposed ixity or transhistorical stability of

22

Hansen, ‘Algorithmic Sensibility’.

28

�Speculation, Transition, and the Passing of Post-cinema

the subject. In other words, we discover here the transformative agency of a mediating layer between subject and object, and this discovery should be seen as an

integral part of the post-cinematic ‘structure of feeling’. Finally, though, we need

to look closer at the way in which the transformation of this mediating layer is

reconiguring our experience, especially with respect to temporality.

Speculative Temporality

Let us recall the uncanny cinematic experience of being ‘present’ to past

events, an experience attributed to the indexical ontology of photographic images. As we have seen, this paradoxical temporal experience rides atop a layer

of complex material interactions that, in some respects at least, are not all too

different from the computational materiality of digital images’ encoding. Nevertheless, it would be wrong to suggest on this basis that post-cinema’s temporality

has not been subjected to a radical transformation. And this temporal shift, as

we shall see, explains in large part the renewed urgency of speculative thought in

the post-cinematic era.

The question of what I am calling post-cinematic temporality is something that

Maurizio Lazzarato has dealt with under the heading of his ‘video philosophy’

— a philosophy of what he calls ‘machines to crystallize time’.23 These machines,

which are exempliied in the video camera and further perfected in digital cameras and computer processors, have a direct line on our becoming-in-time, as they

operate at speeds that far outstrip our cognitive processing and, on this basis, are

in fact capable of modulating our perception itself. For rather than tracing pro-ilmic objects and ixing them photographically as the perceptual objects of vision,

such time-crystallizing machines operate directly on the sub-perceptual lux of

matter, producing images and other sensory contents through material operations

that in no way resemble the perceptual acts to which pre-electronic analogue media (phonography, photography, etc.) are held to be analogous. At stake, above

all, is the increased speed and precision of the microtemporal operationalization

of the mediating layer or interval that, as we have seen, exists between the integral

subjects and objects of any mediated perception. Post-cinematic machines dilate

this interval and hence bypass the molar perspective of the subject. And not only

do they do so at the stage of image capture, but also in computationally based

playback, which is not categorically different in terms of generating images on the

ly, in a carefully timed balancing act between the computational resources and

demands of processors, graphics cards, and competing processes, among other

things. Effectively, then, though these images may be based on a binary code that

serves as a sort of script, they must be generated in ‘real time’ by means of an error-prone and always imperfectly instantiated act of algorithmic ‘interpretation’.

23

Maurizio Lazzarato, Videophilosophie: Zeitwahrnehmung im Postfordismus, trans. by Stephan

Geene and Erik Stein (Berlin: b_books, 2002).

29

�Shane Denson

Such images are ‘executed’ more than they are ‘screened’. These acts of processing and execution are a part of the materiality of post-cinematic images, part of

their volatility and excess with respect to the symbolic register.

There is, of course, a cinematic moment that persists in post-cinematic mediation. Digitized ilms still present themselves to us as quasi-ilmic events, and the

sub-perceptual materiality of computational image processing, logically enough,

goes largely unnoticed in subjective perception. But there is nevertheless a kind

of displacement, a non-actuality, a lack of positivistic self-presence, or what Derrida might call a ‘spectral’ logic implicit in this view of post-cinematic mediation,

and it is important to account for it if we are to understand our current transitional moment. In its absorption into a post-cinematic media ecology, cinema does

not end, but its persistence is less as an actuality than as a quasi-virtual moment,

a kind of memory-image that supplements and explodes the conines of a punctual present or a concluded past. Moreover, post-cinema’s relation to cinema is

not just one of retention (or memory) but also of protention (or anticipation).

It implies what Mark Hansen has called the ‘feed-forward’ logic of twenty-irstcentury media24 — the logic of predictive analytics and algorithmically generated

timelines, playlists, and newsfeeds. It is in this respect, above all, that the temporality of post-cinema diverges from that of cinema.

Post-cinema, with its microtemporal processing, produces essentially postperceptual images; here, what Deleuze called the ‘dividuality’25 of formerly

discrete subjects is enacted at the level of the perceptual object, which is no

longer stamped as a discrete photographic entity but modulated as a variable

and ininitesimally divisible quantity. Such modulation is dependent upon codec

settings, available processing power, bandwidth limitations, and buffering, so

that the pixillated images we see on our digital devices are in a very real sense

‘data visualizations’. And all the while they generate a further stream of data or

metadata that delivers information about our attention and perception to corporate interests like Google, Facebook, Microsoft, or Netlix. This metadata,

it should be pointed out, is not ‘meta-’ in any metaphysical sense of a detached

second-order register; in many ways, it is the primary data, while our sense data

has become secondary or supplemental for the purposes not only of the moneymaking machine but also for the production of sense data to come. Futurity is

implied in this equation in a way that explodes the simple feedback loop as we

have known it. This is not only about surveillance, but about control in a newer,

non-deterministic and non-disciplinary sense — in the sense described by Gilles

Deleuze in his ‘Postscript on the Societies of Control’. Wendy Chun reminds us

that ‘the English term control is based on the French contreroule — a copy of a

roll of an account and so on, of the same quality and content as the original’.26 As

24

Hansen, Feed-Forward.

Gilles Deleuze, ‘Postscript on the Societies of Control’, October, 59 (1992), 3–7 (p. 5).

26

Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, Control and Freedom: Power and Paranoia in the Age of Fiber Optics

(Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006), p. 4 [emphasis in the original].

25

30

�Speculation, Transition, and the Passing of Post-cinema

a verb, to control enters into English in the sense of ‘to check or verify accounts’,

in particular by referring to a duplicate register. But in post-cinematic media the

idea of the register, the record, or the memorial function more generally of control shifts to a future-oriented, protentional one, whereby the subject of perception is actively anticipated or called into existence by means of microtemporal

calibrations of data and sensory streams.

Portending the future, or better: protending it, these media synthesize time

or becoming through the real-time generation of data that point backwards and

forwards at once. Perception itself is dispersed, along with the data of its generation, between here and there, now and then, between the two rolls or scripts,

where the acts of reference and correlation between them explodes the static

‘now’ of either one and enables the generation of new experiences and affects

in real time (or, what amounts to the same, in a microtemporal duration that is

outside the window of subjective perception).

This describes the temporal/experiential dynamics of Autotune, a popular algorithmic voice-modulation program, which Lisa Åkervall has recently analyzed

as an exemplary medium of post-cinematic modulation.27 In this software-based

process, a real-time input (an audio signal) is analyzed and compared to a set of

possibilities (the discrete notes or values inscribed on the contreroule or control

script), subjected to modulation accordingly, and made to correspond to the

acceptable values before the signal is even made available for perception. Past,

present, and future are synthesized here, their discrete natures dissolved in the

interplay of script and counter-script. Of course, it is possible to analyze the situation logically or algorithmically, and to study the exact path of the signal with

the help of technical instruments, so that we might claim that it only appears

that time is subject to transformation. But since it falls beneath the temporal

threshold of perception and thus undercuts or bypasses appearance itself, this

microtemporal processing does indeed revolutionize time for all intents and purposes — which is to say, for all human intentionalities and telic goals, which are