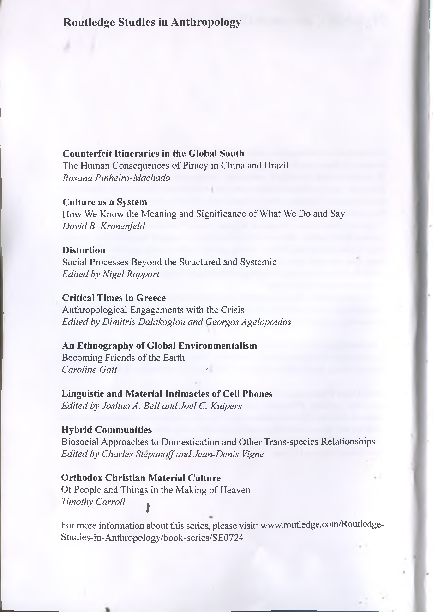

R o u t le d g e S t u d i e s in A n t h r o p o lo g y

C o u n t e r f e i t I t i n e r a r i e s in t h e G l o b a l S o u t h

The H um an Consequences o f Piracy in China and Brazil

Rosana Pinheiro-Machado

C u ltu r e a s a S y s te m

H ow We Know the M eaning and Significance o f W hat We Do and Say

David B. Kronenfeld

D is to r tio n

Social Processes Beyond the Structured and Systemic

Edited by Nigel Rapport

C r it ic a l T im e s in G r e e c e

Anthropological Engagem ents with the Crisis

Edited by Dimitris Dalakoglou and Georgos Agelopoulos

A n E t h n o g r a p h y o f G lo b a l E n v ir o n m e n t a lis m

Becom ing Friends o f the Earth

Caroline Gatt

•

L in g u is tic a n d M a t e r ia l I n tim a c ie s o f C e ll P h o n e s

Edited by Joshua A. Bell and Joel C. Kuipers

H y b r id C o m m u n itie s

Biosocial Approaches to D om estication and Other Trans-species Relationships

Edited by Charles Stepanoff and Jean-Denis Vigne

O r t h o d o x C h r is tia n M a t e r ia l C u ltu r e

O f People and Things in the M aking o f Heaven

Timothy Carroll

^

For more infonnation about this series, please visit: www.routledge.com/RoutledgeStudies-in-Anthropology/book-series/SE0724

�H y b r id C o m m u n itie s

Biosocial Approaches to

Domestication and Other

Trans-species Relationships

E d ite d b y C h a r le s S te p a n o f f

a n d J e a n - D e n is V ig n e

Routledge

Taylor & Francis Group

LON DON AN D N EW YORK

�First published 2019

by Routledge

2 Park Square, M ilton Park, A bingdon, O xon 0 X 1 4 4RN

and by Routledge

7 1 1 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

R o u t l e d g e is a n im p r in t o f th e T a y lo r & F r a n c i s G r o u p , a n in f o r m a b u s in e s s

© 2019 selection and editorial matter, C harles StepanofT and Jean-D enis

Vigne; individual chapters, the contributors

The right o f Charles StepanofT and Jean-D enis Vigne to be identified as

the authors o f the editorial material, and o f the authors for their individual

chapters, has been asserted in accordance w ith sections 77 and 78 o f the

Copyright, Designs and Patents A ct 1988.

All rights reserved. No part o f this book may be reprinted or reproduced or

utilised in any form or by any electronic, m echanical, or other m eans, now

known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in

any inform ation storage or retrieval system , w ithout perm ission in w riting

from the publishers.

T r a d e m a r k n o t i c e : Product or corporate nam es may be tradem arks or

registered tradem arks, and are used only for identification and explanation

w ithout intent to infringe.

B r i tis h L i b r a r y C a t a l o g u in g - i n - P u b l ic a t io n D a t a

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

L i b r a r y o f C o n g r e s s C a t a lo g i n g - i n - P u b li c a t i o n D a t a

N am es: StepanofT, Charles, editor. | Vigne, Jean-D enis, editor.

Title: Hybrid com m unities : biosocial approaches to dom estication and

other trans-species relationships / edited by Charles Stepanoff and

Jean-D enis Vigne.

Description: A bingdon, Oxon ; N ew York, N Y : Routledge, 2018. | Series:

Routledge studies in anthropology ; 46 | Includes bibliographical

references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017058517 (print) | LCCN 2018016153 (ebook) |

ISBN 9781315179988 (ebook) | ISBN 9781351717984 (w eb pdf) |

ISBN 9781351717977 (epub) | ISBN 9781351717960 (m obi/kindle) |

ISBN 9781138893993 (hardback : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Dom estication. | Nature— Effect o f hum an beings on. |

Hum an-anim al relationships. | H um an-plant relationships.

C lassification: LCC SF41 (ebook) | LCC SF41 .H94 2018 (print) | DDC

636— dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017058517

ISBN: 978-1-138-89399-3 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-315-17998-8 (ebk)

Typeset in Tim es New Roman

by A pex C o Vantage, LLC

MIX

Paper from

responsible sources

FSC" C 013985

P ri nt ed in t he U n it ed K i n g d o m

b y H en r y L ing L im i ted

�C o n te n ts

List o f figures

List o f tables

List o f contributors

ix

xi

x iii

I n tr o d u c t io n

1

CH A RL E S STE PA N O FF A N D JE A N -D E N IS VIG NE

PAR TI

L im in a l p r o c e s s e s : b e y o n d th e w ild a n d th e d o m e s tic

21

1

23

A g e n e t ic p e r s p e c t iv e o n th e d o m e s tic a tio n c o n t in u u m

L A U R E N T A. F. F R A N T Z A N D G R E G E R L A R S O N

2

S e lf - d o m e s t ic a t io n o r h u m a n c o n tr o l? T h e U p p e r

39

P a la e o lit h ic d o m e s tic a tio n o f th e w o l f

M IE TJE G E R M O N P R E, M A RTIN A L A Z N l£ K O V A -G A L E T O V A ,

M I K H A I L V. S A B L I N A N D H E R V E B O C H E R E N S

3

B e y o n d w ild a n d d o m e s tic : h u m a n c o m p le x r e la t io n s h ip s

65

w ith d o g s , w o lv e s , a n d w o lf - d o g h y b r id s

N ICO LAS LESCU REU X

4

W ild g a m e o r fa r m a n im a l? T r a c k in g h u m a n - p ig r e la t io n s h ip s

in .a n c ie n t tim e s th r o u g h s t a b le is o to p e a n a ly s is

81

M A RIE BA L A S SE , TH O M A S CU CC H I, A LLO W E N EV IN ,

A D RIA N BA L A S ES C U , D ELP H IN E F RE M O N D EA U AND

M A R1E-PIERRE H O R A RD -H ER BIN

5

A r a b le w e e d s a s a c a s e s t u d y in p la n t- h u m a n r e la t io n s h ip s

97

b e y o n d d o m e s tic a tio n

A M Y B O G A A R D . M O H A M M E D A T E R A N D J O H N G. H O D G S O N

t

�vi

Contents

P A R T II

H o w d o m e s tic a tio n c h a n g e s h u m a n s ’ b o d ie s a n d s o c ia lity

6

From

fighting against t o becoming with :

v ir u s e s

a s c o m p a n io n sp e c ie s

CH A RL O TT E BRIV ES

7

M i l k a s a p i v o t a l m e d i u m in t h e d o m e s t i c a t i o n o f c a t t l e ,

s h e e p a n d g o a ts

M E L A N I E R O F F E T - S A L Q U E , R O S A L I N D E. G I L L I S ,

R I C H A R D P. E V E R S H E D A N D J E A N - D E N I S V I G N E

8

W a tc h in g th e h o r s e s : th e im p a c t o f h o r s e s o n e a r ly

p a s t o r a l i s t s ' s o c i a l i t y a n d p o l i t i c a l e t h o s in I n n e r A s i a

GALA ARGENT

P A R T III

S h a r e d p la c e s , e n ta n g le d liv e s

9

G r o w in g a s h a r e d la n d s c a p e : p la n ts a n d h u m a n s o v e r

g e n e r a tio n s a m o n g th e D u u p a fa r m e r s o f n o r th e r n C a m e r o o n

E R IC G A R I N E , A D E L I N E B A R N A U D A N D C H R I S T I N E R A I M O N D

10

F ig a n d o liv e d o m e s tic a tio n in th e R if, n o r t h e r n M o r o c c o :

e n ta n g le d h u m a n a n d tr e e liv e s a n d h is t o r y

Y ILD IZ A U M EE RU D D Y -T H O M A S A N D Y O U N ES H M IM SA

11

C o o p e r a t in g w it h th e w ild : p a s t a n d p r e s e n t a u x ilia r y

a n i m a l s a s s i s t i n g h u m a n s in t h e i r f o r a g i n g a c t i v i t i e s

E D M O N D D O U N IA S

12

W h y d id th e K h a m t i n o t d o m e s t ic a t e t h e ir e le p h a n t s ?

B u ild in g a h y b r id s o c ia lit y w ith ta m e d e le p h a n t s

N I C O L A S L A IN E

13

C o g n itio n a n d e m o t io n s in d o g d o m e s tic a tio n

SARAH JE AN NIN

�Contents

vii

P A R T IV

O n g o in g tr a n s fo r m a tio n s

249

14

251

D o m e s tic a tio n a n d a n im a l la b o u r

JO CELY N E P O R CH ER A N D SO PH IE N ICO D

15

H u m a n - d o g - r e i n d e e r c o m m u n i t i e s in t h e S i b e r i a n

A r c t ic a n d S u b a r c tic

261

K O N S TA N TIN K L O K O V A N D V L A D IM IR DAVYD OV

16

D o m e s t ic a t in g th e m a c h in e ? (R e ) c o n f ig u r in g d o m e s tic a tio n

p r a c t ic e s in r o b o tic d a ir y f a r m in g

275

S EV ER IN E L A G N EA U X

17

F r o m p a r a s ite to r e a r e d in s e c t: h u m a n s a n d m o s q u it o e s

in R e u n io n I s la n d

289

SA N D R IN E DUPE

Index

к

302

\

�F ig u r e s

I

0.1

1.1

2.1

2.2

4.1

4.2

4.3

4.4

5.1

5.2

5.3

.7.1

7.2

,

H ybrid communities.

Schem atic o f various m odels o f dom estication and their effect

on genetic diversity.

Dorsal view o f a Pleistocene w o lf skull from the Gravettian

Predm osti site.

Dorsal view o f the Palaeolithic dog skull from the Goyet cave.

Results from stable carbon (813C) and nitrogen (515N ) analysis

o f bone collagen from pigs, sheep and hum an remains from the

m ediaeval city o f York.

Reliance o f pigs on dom estic farm ed food (millet, animal

protein scraps) in Dadiw an in ancient China, as evidenced

from stable isotope com position o f bone collagen.

Gradual changes through time in pigs’ diet in Xiaw anggang,

with an increasing contribution o f m illet and animal proteins.

A: Stable isotope ratios in bone collagen o f the main species

from the Gum elni(a culture assem blages at Bordu?ani-Popina,

Har§ova-tell and Vitane§ti-M agurice. B : Stable isotope ratios in

bone collagen from suids with small ‘dom estic’, large ‘w ild’ and

large ‘dom estic’ m olars (from geom etric m orphom etric analyses).

D isplay o f gathered plants including w eedy Malva spp., market,

Jeblia, R if region, M orocco.

Vicia sativa subsp. nigra, growing as a w eed o f cereals in the

oasis o f Im in-o-Iaouane on the southern slopes o f the High Atlas,

M orocco.

H arvested decrue barley field, showing spiny weeds (Echinops

spinosus), Guelm im province, Morocco.

Proportion o f animal fat residues identified as m ilk fats, ruminant

and non-rum inant adipose fats and aquatic fats in archaeological

sherds from the N eolithic in Europe and the N ear East.

Detail o f a m ilking scene from rock art in a rockshelter at

Tasigmet, Oued Djerrat (Tassili-n-Ajjer).

7 .3

H y p o t h e tic a l c a tt le k i l l - o f f p r o f ile s .

8.1

Reconstruction o f the Berel 11 burial mound.

\

12

25

43

44

84

87

89

91

101

102

103

133

135

136

147

�x

Figures

8.2

8.3

8.4

9.1

9.2

9.3

10.1

10.2

10.3

11.1

12.1

12.2

12.3

12.4

15.1

15.2

16.1

16.2

Typical Pazyryk bridle structure with both the headstall (3) and

throat latch (4) fastening on the horse’s left side.

Scythian arm or and weaponry.

Pazyryk shields.

Sorghum is represented by a large diversity in the D uupa

subsistence system from cultivated to wild m orphotype.

Leaving in weeds.

Children sorting leaves.

Children in the Bni Ahmed region caprifying a fig tree, Rif, northern

Morocco.

Large m ixed fig, olive and cereal agroecosystem , Rif,

northern Morocco.

Oleasters grafted with olive varieties within a tended orchard

in Sidi Redouane, Rif, northern Morocco.

D om esticated and npn-dom esticated auxiliary anim als assisting

humans in their foraging activities.

Elephant tied to the lak chang.

Learning commands.

Ivory statue representing Utingna.

The relational dynam ics between the Khamti and elephants.

Ratio o f reindeer, sled, pastoral, and hunting dogs in the nomadic

households o f the Russian North, according to the data from the

Polar Census o f 1926-1927.

Ratio o f reindeer, sled, pastoral, and hunting dogs in settled

households o f the Russian population o f the Russian North,

according to the data from the Polar Census o f 1926-1927.

The view from M arc’s office o f the entirety o f the robotic stable,

Belgium, August 2016.

M arc at his office computer, w hich shows a lactation curve

in decline, Belgium, July 2017.

JL

153

155

155

171

173

174

184

185

187

208

223

225

228

230

263

264

276

282

�T a b le s

2.1

2.2

2.3

7.1

11.1

15.1

15.2

17.1

17.2

17.3

17.4

17.5

Com parison o f canid products (cf. Sigaut, 1980) in the

ethnographic and archaeological (U pper Palaeolithic) record

(non-exhaustive list).

Com parison o f possible forms o f familiarization o f wolves

(cf. Sigaut, 1988) in the ethnographic and archaeological

(U pper Palaeolithic) record (non-exhaustive list).

Com parison o f possible forms o f appropriation o f captive

w olves/dogs (cf. Sigaut, 1988) in the ethnographic and

archaeological (U pper Palaeolithic) record (non-exhaustive list).

Com position o f cow, sheep, goat and hum an milk.

Profiles o f wild and untam ed auxiliary anim als assisting humans

in their foraging activities.

N um ber o f people, dogs, and reindeer in the households o f

the Russian North. Calculated on the basis o f data from the

1926-1927 Polar Census.

Main typological groups o f HDR communities.

The dom esticity o f m osquitoes, as an encom passing category,

according to M ason’s categories (1985).

The dom esticity o f m osquitoes from the gardens, according to

M ason’s categories (1985).

The dom esticity o f experim ental mosquitoes, according to

M ason’s categories (1985).

The dom esticity o f released m osquitoes, according to M ason’s

categories (1985).

The dom esticity o f Reunionese Aedes albopiclus, according to

M ason’s categories (1985).

*

48

51

53

128

210

262

266

292

293

296

297

299

�15

H u m a n -d o g -r e in d e e r

c o m m u n i t i e s in t h e S i b e r i a n A r c t i c

a n d S u b a r c tic

Konstantin Klokov and Vladimir Davydov

M ost research on animal dom estication focuses on the relationships between

hum ans and one particular species. However, only the dog, the first species to

be dom esticated, enjoyed the exclusivity o f being the sole domestic animal pres

ent when it was integrated into hum an societies. All other anim als dom esticated

thereafter had to adapt to a new environm ent peopled not only by humans, but

also by other species, even if only the dog. A nthropized environm ents were more

exactly anthropo-canified environm ents. In this chapter, we investigate dom es

tication processes through the interactions between three species: humans, dogs

and reindeer in N orth Asia. H ow can these three species negotiate a shared liveli

hood, coexist and even cooperate in spite o f their differences in needs and behav

ior? H ow does each species change the biosocial environm ent o f the other two?

W hat kind o f different hybrid com m unities do they shape in the different cultural

and-ecological contexts o f the North?

The purpose o f this chapter is to investigate the synergy o f collaborative activi

ties o f hum ans, dogs, and reindeer in hybrid com m unities (hereafter H D R com

m unities) in northern Russia. To do this, we utilize data from the 1926-1927 Polar

Census, a unique project initiated by the Soviet Central Statistical A dm inistra

tion to gather prim ary data on the whereabouts, economy, and living conditions

o f the population living in the Arctic and Subarctic (Pokhoziaistvennaia perepis’

1929; A nderson 2011); we have supplem ented this with inform ation from literary

sources from the early 1900s and data from our own fieldwork in different regions

o f Siberia. These sources o f inform ation allow us to present a fairly complete

picture o f the coexistence and mutual activities o f anim als and hum ans in HDR

com m unities in tundra, taiga (boreal forest), m ountainous, and coastal (m aritime)

landscapes. The Polar Census contains data on ju st over 33,000 nomadic and

settled local households, 270,000 people, 100,000 dogs, and 1,800,000 reindeer

(Table 15.1).

The Polar Census prim arily registered households involved in reindeer herding,

fishing, and hunting for fur-bearing animals, sea m ammals, ungulates, waterfowl,

and upland gam e birds ( Tetraonidae), as well as gathering berries, mushrooms,

birds’ eggs, and m any other items. The area covered by the Polar Census was a

special region, which in Russia is usually called the North or Far North. Accord

ing to the data from the Polar Census, 35.4% o f its population was nomadic, and

�262

Konstantin Klokov and Vladimir Davydov

T a b le 1 5 .1 N u m b e r o f p e o p l e , d o g s , a n d r e i n d e e r i n t h e h o u s e h o l d s o f t h e R u s s i a n

N o r t h . C a l c u l a t e d o n t h e b a s i s o f d a ta f r o m

th e

1 9 2 6 -1 9 2 7

P o la r C e n s u s

( P o k h o z ia is t v e n n a ia p e r e p is ’ 1 9 2 9 ).

S e t t l e d h o u s e h o ld s

N o m a d ic h o u s e h o ld s

T o ta ls

3 3 ,6 4 1

2 3 ,4 2 9

5 7 ,0 7 0

1 6 4 ,5 8 7

1 0 6 ,2 6 3

2 7 0 ,8 5 0

H o u s e h o ld s w ith d o g s

1 3 ,4 1 9

8 ,3 5 4

2 1 ,7 7 3

A d u lt s le d d o g s

4 8 ,6 6 6

5 ,8 1 7

5 4 ,4 8 4

A d u lt h u n tin g d o g s

9 ,6 2 6

4 ,9 8 2

1 4 ,6 0 8

A d u lt p a s to r a l d o g s

1 ,2 6 7

1 0 ,2 8 4

1 1 ,5 5 1

1 6 ,8 2 8

5 ,3 8 0

2 2 ,2 0 8

H o u s e h o ld s

P e o p le

D ogs u nder 1 year o f age

4 ,2 1 8

9 ,6 5 4

1 3 ,8 7 2

G r o s s r e in d e e r h o ld in g s

7 8 ,5 4 0

1 ,7 3 2 , 2 3 1

1 ,8 1 0 , 7 7 1

T r a n s p o r t r e in d e e r

3 6 ,4 5 8

3 6 4 ,8 0 0

4 0 1 ,2 5 8

H o u s e h o ld s w ith r e in d e e r

the rem aining 64.6% were residents o f small villages and trading posts. These

included com m unities from m ore than 20 different indigenous northern peoples

speaking different languages, and small groups o f R ussians who had interm ar

ried with them. The latter partly adopted the aboriginal populations’ lifestyles.

We argue that in these northern com m unities, cooperation between people, dogs,

and reindeer, through w hich various forms o f traditional econom y developed,

successfully existed, and were transform ed through various historical processes.

A t the same time, the role played by people, reindeer, and dogs, and the func

tions that each category carried out in these sym biotic com m unities, changed in

response to political, economic, and social challenges, some o f which emerged

from the center o f Russia.

Cooperation was achieved through a variety o f innate and acquired abilities and

practices o f each o f the three participants in the HDR community. Some o f these

abilities are probably genetic, while others have been acquired in the course o f

their joint activities (Stepanoff 2012). Particular abilities were tied to each indi

vidual’s intrinsic characteristics, while others were worked out in the course o f

their joint activities. The developm ent o f relevant capacities allows everyone to

contribute to the overall synergistic activity o f the community, nam ely to perform

a specific set o f functions forming an integrated part o f every type o f com m u

nity in various forms and com binations. On the one hand, these com binations

depended on local conditions - relations o f the com m unity w ith the natural “sus

taining” landscape. On the other hand, they were also contingent on the historical

traditions o f each ethnic group. As a result, even w ithin very sim ilar types o f envi

ronments, the structure o f H D R com m unities and the roles o f each o f the three

participants were often significantly different.

H u m a n -d o g -r e in d e e r h o u s e h o ld ty p o lo g ic a l g r o u p s

The m aps w hich in Figures 15.1 and 15.2 m ade it possible to characterize H D R

com m unities in all o f the 56 census areas, are based on the data provided by the

���Human-dog-reindeer communities in Siberia

265

Polar Census. Nom adic (Figure 15.1) and settled (Figure 15.2) households were

presented in the materials o f the Polar Census separately, while settled households

were further divided into sedentary indigenous and settled Russian groups. The

ratio o f dogs and reindeer in nom adic and settled households significantly var

ied, but the differences between Russian and indigenous settled households were

rather small.

Nom adic households in the tundra possessed by far the largest percentage

(95.7% ) o f all reindeer. They also had the largest reindeer herds, the m ajority o f

w hich were kept largely as sources o f m eat and skins. In contrast, the nomadic

peoples o f the taiga, as well as m any settled native and Russian households,

kept reindeer prim arily as transport animals. Since they required relatively few

transport reindeer, their herds were not as large as those o f the tundra nomadic

households.

Sedentary households owned the largest percentage o f dogs (74.3%), and these

were categorized in the census data as sled dogs. The nom adic groups em ployed

reindeer sleds or rode on reindeer, and in turn had a small num ber o f sled dogs,

or som etimes none at all. In the census data, m ost nom adic households also pos

sessed pastoral dogs, while hunting dogs were present both in nomadic and settled

families (Table 15.1).

The analysis o f the data from the Polar Census in a regional context where we

used ju st one formal criterion - the ratio o f dog and reindeer num bers - allowed

us to distinguish six m ain typological groups o f H D R com m unities (Table 15.2).

The first group includes households o f sea m am m al hunters and fishers (mainly

Chukchis, Eskim os, Koryaks, and Russians) living on the coasts o f the Pacific and

the Arctic oceans. As a rule, these households had no deer, and possessed m any

sled dogs, w hich form the prim ary m eans o f w inter transportation. Dogs were also

particularly critical in hunting seals and polar bears. To date, however, sled dogs

have alm ost entirely disappeared in these areas. In C hukotka and Kam chatka dog

sledding has now becom e m ostly a hobby. Since 1991 dog sled races have regu

larly taken place in which 10-20 sleds travel several hundred kilom eters along the

coast o f the Pacific O cean (B ogoslovskaia 2011: 38-65). Furtherm ore, dog sled

races have also become an im portant part o f Reindeer herder’s day celebrations in

Dolgan villages in Taimyr (D avydov - Taimyr Peninsula field notes).

The second group o f HDR com m unities is based on the large herds o f rein

deer, w hich people keep prim arily as sources o f m eat and that take part in annual

m igrations across the tundra, som etimes traveling hundreds o f kilometers. This is

com m on in the western part o f the Russian Arctic in N enets and Kom i-Izhem tsy

nom adic households, where dogs are com m only actively involved in herding

large groups o f deer. The other groups engaged in reindeer herding in the tundra

possessed m uch sm aller num bers o f herding dogs. However, by the m id-twentieth

century, reindeer herding dogs had becom e widely used in eastern tundra areas

(B askin 2 0 0 9 :2 5 1 ,2 5 5 ).

The third group characterizes nom adic households o f eastern Chukotka and the

Koryak okrug (district) o f the Kam chatskii krai (region), northern Kamchatka.

These households have large reindeer herds, but alm ost no herding dogs, while

�. 3

h §c §

(N

. ! S.-S

1 S) s

in

Ш

О

О

СП

О

CN

CN

r-

40

©

О

о

О

V.

s i

^3 <*>

*5 §

-S

s i

о

ON

o^

CN

a -a

\з О $

S \ -s :

t:

54.

|

Ъ)

4®

o '

rО

00

£

i

2 .4

s

l

r-

so

o '

О

00

00

cn

CN

«П

ON

О

cn

N°

0s

4®

o '

IT)

in

in

so

e '

en

ON

40

N®

O'

CO

Tt*

8 .4

*

8 .3

-§

V.

s*.

*“

о

«С

*iJ

4^ ^^

R

5 .?:

a

I g -i

-c

a :§

00

V I 'S

s? .§ g

NT

o '

О

40

v.

^ a

<3 $ ^

i.- s s

fe; 'o'-§

00

r00

So

N°

0s

N©

O'

en

in

4O '

O'

40

1— 1

cn

cn

TfON

cn

en

CN

CN

ЯW l c

о H Д 00 о

2 £ < ыz

T3

IS *

CN

40

О

CN

»n

*—1

ON

^

2 £ £^

~5:

s:

.o

ON

О

CN

<u

s

1)

СЛ

12

e

о

Z

■s

sо

Z

N°

О4

-p

o '

CN

40

40

ON

40

О

in

CN

40

CN

en

CN

00

ON

*—i

=

G

О

'o b

<

U

>>*73

сл

я

о g

-t-< Л

^

o '

о

^2

3

и

|,9! и

^ Он

с<D

СЛ

I

<3

£

с ^ а>^ -н -з .s g .2

1

I

S..S 1 .5 л § § • ? 3

£

d o g s fo r d iffe r e n t a im s

1

�Human-dog-reindeer communities in Siberia

267

some sled dogs are to be found nearly everywhere. A lthough this looks strange

at first glance, this general pattern can be explained. Historically, Chukchi can be

divided into nom adic reindeer herders o f the tundra, who traveled with the help

o f reindeer, and sedentary sea hunters and fishers who lived on the coast and used

dog sleds as the main means o f conveyance. H ouseholds from these two Chukchi

groups m aintained ties with each other, including through family visits to each

other’s homes (Vate 2005). Sled dogs in the coastal households were not accus

tom ed to reindeer, and could attack and bite the visiting sled deer while they were

tethered in the m arine com m unities. Therefore, reindeer herders often traveled

with dog sleds instead o f reindeer sleds when visiting the sea coast (K lokov Chukotka field notes).

The fourth group o f H D R households is characterized by nomadic populations

in the taiga. These com m unities included a small num ber o f well-tam ed reindeer,

most o f which were used as riding and/or cargo (pack) reindeer. W hile herding

dogs were absent, hunting dogs played critical roles in these households. Human

hunters in these households, riding on deer, would follow the hunting dogs who

would lead them to anim als such as squirrel and sable. Hunting fur anim als rep

resented the m ain source o f income for nom adic taiga households. Furtherm ore,

dogs helped to hunt elk and bear. In these types o f hunts, transport reindeer helped

to cover large distances in the taiga.

This type o f H D R household, widely spread across the Siberian taiga in the

past, is now practiced only in particular areas. M echanical transport, in particular

snowm obiles and tracked vehicles, has nearly nullified the benefits o f hunting

with reindeer. The num ber o f reindeer herder families who continue to nom adize

the taiga is now extrem ely small. Such households still can be found in parts

o f Yakutia, as well as in some areas o f the Irkutskaia and A m urskaia regions

(oblasti), the republics o f Buryatia and Tuva, and K habarovskii and Zabaikal’skii

regions (kraia ).

The fifth group includes sedentary households that held a significant num ber

o f reindeer (so-called izbennoe olenevodstvo; K oz’m in 2003: 95-122). This type

o f household was com m on m ostly for Russian populations (Pom ors) in the Kola

Peninsula. Sim ilar households can also be found in some areas o f Yakutia. People

in these households kept a small num ber o f dogs m ostly for hunting. This type

o f farm disappeared in the m iddle o f the tw entieth century, when reindeer were

replaced by m echanical transport.

Com m unities where reindeer and dogs were present in small num bers we ten

tatively attributed to the sixth, and last, group.

I n te r a c tio n s a n d r o le s in H D R h o u s e h o ld s

Here we will describe the com plem entary roles and the requirem ents o f the three

species involved in these communities.

Humans overall played a series o f roles in relation to dogs and reindeer. H erd

ers o f course supervised and guided the m ovem ent o f reindeer herds, as a kaiur,

or sled driver, and people guided reindeer and dogs who pulled sleds, transporting

�268

Konstantin Klokov and Vladimir Davydov

people or cargo. People also directed riding deer that carried them upon their

backs, as well as transport reindeer, w hich were loaded with cargo. Hunters

worked in com bination with dogs and reindeer in pursing fur-bearing animals

as well as ungulates, with the reindeer carrying the person, and the dog leading

both to the prey. All o f these ways o f interacting with reindeer and dogs involved

hum an attentiveness and acts o f care and protection. Both reindeer and dogs som e

times required protection from predators, and both would have to be appropriately

interacted with (“tam ed”) to help ensure they w ere suitably prepared for their

required roles. Dogs and reindeer were selectively bred, which was achieved

through isolating choice anim als with one another, and by rem oving anim als from

the breeding pool by killing or castrating them. Further, reindeer (far more so than

dogs) had to be killed and transform ed into food, clothing, dwellings, and other

things. All o f these practices involved yet other sets o f things - sleds, harnesses,

saddles, fences, knives, containers, fires, dwellings, entire landscapes - m any o f

which required construction and m aintenance (Anderson etal. 2017).

The spatial dim ension o f people’s relationships with these anim als is o f great

importance. However, the explanatory m odels o f hum an-anim al relations often

focus on hum an choices and underestim ate the role o f animal agency in this pro

cess (S tepanoff 2017). Generally, people in various ways try to lim it and direct

the m ovem ent o f dogs and deer while, at the same time, m ove in a particular geo

graphical area, taking into consideration the interests and needs o f their animals.

To a large extent people “adjust” their seasonal rhythm s to the grazing require

m ents o f reindeer, as well as to the needs and capabilities o f dogs.

Reindeer provided hum ans a range o f raw m aterials such as meat, skins, ant

lers, and milk, but also gave them labor by pulling and carrying people and goods,

and acted as decoy anim als (Rus. manshchiki) for “wild” deer during hunting.

In the tundra, reindeer can supply people with food, clothing, and m aterials for

nom adic dwellings, and, moreover, every year transported nom adic families and

their belongings for m any hundreds and even thousands o f kilometers. In the

taiga, reindeer m ade the same contributions, but to a sm aller degree. In the tundra,

reindeer herding could be the prim ary and even the sole hum an occupation, but in

the forest, herding was always com bined with other activities, m ost often hunting,

w hich as a rule was the main source o f income. By the early tw entieth century,

tundra reindeer herding was already heavily involved in trade relations. Thus, the

average herd size in a reindeer Kom i Izhem tsy herder household in the tundra

docum ented by the Polar Census was 755.7 anim als and in w estern Chukotka

622.8 head. In contrast, in the taiga people bred reindeer prim arily as transport

animals, rather than as sources o f meat, and the average size o f a herd usually did

not exceed 50-70 head.

Partially as a result o f these radically different herd sizes, reindeer-huinan daily

and long-term interaction also differed between the tundra and taiga. In the forest,

the process o f dom estication had an individual character: hum ans closely worked

w ith each calf, starting from the day it was bom . To do this, in some areas o f the

taiga calves are tethered with ropes im mediately after their birth (D avydov 2014).

This close daily deer-hum an socialization meant that reindeer came to know

�Human-dog-reindeer communities in Siberia

269

hum ans relatively well and showed little fear o f them. Such taiga reindeer can

be left for “free-grazing” for a few m onths without hum an surveillance with little

fear that they will becom e “w ild” prior to rejoining hum ans later in the year. In the

tundra, where interactions w ith reindeer are far less direct and intensive, herders

have to constantly m onitor their herds. To do this, people take turns keeping watch

over a herd around the clock (this is typical for N enets and Kom i-Izhem tsy) or

at certain intervals, perhaps once a day or every 2 -3 days, when the w hole herd

is collected together. In a sense, m any tundra deer are m anaged as a single unit,

while only sled reindeer are taught and trained individually.

The places and architectures o f interacting with reindeer in the taiga differ sig

nificantly from those used in the tundra. For example, it was com m on in the taiga

to use smudges, or smoky fires, to protect reindeer from insects. In the warm sea

son, some people built special sheds consisting o f poles and branches to provide

shade for reindeer, since reindeer are very sensitive to overheating. Gathering

reindeer near a sm udge serves as a daily m eans for people to check on their pres

ence and condition, but this is not a one-sided affair - the reindeer benefit from

this, too, acquiring shelter from the sun and insects. In the taiga, people tradition

ally also used fences to keep reindeer, but not all year round: they did this only for

a few months. Fawns are pets both am ong tundra and taiga reindeer herders, and

can som etimes enter hum an dwellings. Such pets are most often deer that were

left without their m others to nurse them. They eat bread from hum an hands and

generally do not live near the herd, but rather stay near people. A fter they have

m atured and can feed w holly on their own, they continue to approach dwellings,

seeking out hum an food.

Reindeer dietary needs also were intertwined with hum an activities. Salt was an

im portant elem ent o f interacting w ith reindeer that gathered near smudges. R ein

deer require some salt in their diet, but it is difficult for them to procure it on their

own, and the deer in effect use people to obtain it for them . Salt is poured on large

stones or roots o f trees, put in w ooden troughs m ade from logs, or even provided

to them directly from the hand. Reindeer consum ption o f this salt keeps them in

close proxim ity to hum ans (and som etimes also dogs), helping to m aintain their

familiarity.

O ver the past decades, dom estic reindeer have unwittingly undertaken a new

and im portant role in Russia - a political one. These anim als have becom e an eth

nic m arker and a cultural symbol o f indigenous peoples o f Siberia, and this role

in ethnic politics is rapidly becom ing increasingly important. Images o f reindeer

can be seen in the crests o f several northern regions o f Russia on the arms o f the

M urm ansk oblast’, Yamalo-Nenets A utonom ous District, as well as on several

dozen arms o f m unicipalities (districts, cities) o f northern Russia.

In this regard, reindeer herding in R ussia is referred to as the “ethno-saving”

branch o f the economy, as the nom adic way o f life o f reindeer herders is said to

allow them to m aintain some cultural distance from the rest o f society, helping

to avoid assim ilation. Thus, as a result o f the mutual adaptation o f hum ans and

reindeer to each other, thousands o f reindeer herder families live alm ost all year

round with their anim als and do not have direct contact with other hum an groups.

�270

Konstantin Klokov and Vladimir Davydov

Dogs in H D R com m unities perform ed a variety o f functions. They pulled sleds,

som etimes carried loads on their backs, helped people m anage reindeer herds,

and participated in various types o f hunting. Am ong the latter, the m ost im portant

were: hunting fur-bearing anim als (sable, squirrel, etc.), large anim als (ungulates

and large predators), upland game, waterfowl, and seals on the ice.

Dogs developed special skills while undertaking these activities, w hich they

learned by w orking in concert with humans, other dogs, and reindeer. “U niversal”

dogs that sim ultaneously acquired several such skills were rare. Sometim es dogs

and people also pulled loaded sleds together, dogs and people slept next to one

another to share each other’s body heat. In som e cases, dogs’ bodies were used as

sources o f food and-their fat as a m edicine for lung diseases. However, the needs

and capabilities o f dogs im pose serious limitations on the m obility o f people.

For example, for a trip on a dog sled, one needed to consider beforehand how to

provide food (fish or meat) for the animals, w hich exert significant amounts o f

energy during such trips. W hen hunting for sable or squirrel in the fall (which is

the m ost productive period for hunting these animals), dogs m ust run through the

snow, w hich tends to become progressively deeper as the season unfolds. W hen

the snow becomes too deep for dogs, a hunter either com pletely abandons hunting

and returns hom e, or continues hunting using traps.

Living together w ith humans, dogs instinctively perform the signal-guard func

tion, warning o f approaching bears, other predators, and strangers, as well as driv

ing predators away. At the same time dogs use hum ans for protection and defense

from the same predators. In the taiga and tundra, dogs are not ju st watchdogs

who guard dwellings; they usually also accom pany everyone who goes hunting,

fishing, and picking m ushroom s or berries outside the village, and warn them o f

danger by barking. In recent years, their im portance in such roles has increased

along with the growing num ber o f brow n bears, w hich now represent a m ore com

mon threat to residents across the Siberian taiga and even tundra.

R e c ip r o c a l le a r n in g

The relationships between dogs and deer are especially interesting and highly

variable. Dogs from settlements, as well as hunting dogs, w hich are unaccustom ed

to reindeer, can injure reindeer. Dogs living together w ith herders pass a rigorous

selection process with regard to their loyalty to reindeer. People severely punish

dogs w hich show aggression to reindeer, and if this is not enough, kill them.

The classical reindeer herding laika is a dog o f small size. A ccording to Nenets,

a small dog is convenient for the safety o f calves and because it is easier to trans

port it on sleds. One m ight assum e that the training o f reindeer herding laikas

requires a significant num ber o f special techniques. However, N enets reindeer

herders usually do not agree with such statements, but rather em phasize the innate

ability o f the N enets laikas and their ability to learn from older dogs. They do

not teach dogs specially: a dog either is bom w ith certain abilities, and in part

improves upon them or learns them from older dogs. Thus, Nenets reindeer herd

ers said:

�Human-dog-reindeer communities in Siberia 271

N enets reindeer herding dogs are able to pasture reindeer as if they got this

from God. R ussian dogs, as well as the Russian people - they do not know

how to do this. The older dog teaches the younger. Even a bad dog is better

than nothing, as reindeer see a dog and gather them selves in a group.

(Klokov - Yamal Peninsula field notes)

These insights o f reindeer herders are confirm ed by observations o f ethologists,

who argue that all highly skilled herding dogs emerge as a result o f intrinsic char

acteristics and learning (Baskin 2009: 152-153; Coppinger and Feinstein 2015).

This is in part learned from watching other dogs, and is to some extent taught by

the herders, whose initial task is to prevent a puppy from driving deer aimlessly.

The main way in w hich herding dogs engage with reindeer is to push deer that

have drifted from the main group back towards the herd. This task the dog per

forms itself. This perform ance is facilitated by the fact that the frightened reindeer

in most cases turns toward, and merges into, the herd, regardless o f w hich way

a dog initially chases them. As soon as a reindeer herder is sure that the reindeer

have turned and m oved to the herd, he calls the dog back to him. In addition, the

dog, ju st like a w o lf beginning to prey on reindeer, usually does not break into the

herd, w hich now presents itself as a dangerous mass o f swiftly m oving feet and

antlers, but rather rushes along its edges, m aking the reindeer stay close to each

other. This is exactly w hat reindeer herders need (Baskin 2009: 152-153).

All reindeer herders em phasize that people do not play a leading role in the

training o f a young dog, but rather that the young dog prim arily learns by m im ick

ing the behavior o f older, m ore experienced dogs. The same opinion exists am ong

taiga hunters concerning the training o f hunting dogs. However, if he does not

possess an experienced dog, a hunter trains the young dog him self, perform ing the

actions usually carried out by a m ore experienced dog. For example, he can find

a sable in a tree in order to show it to the young dog, or he can run along with the

dog following the tracks o f a sable. Despite the fact that the dogs teach each other,

reindeer herders believe that the w orking qualities o f a dog also depend on his or

her master: “There are people who cannot train the dogs, and the dogs w ork well

with some others. I f a person has a dog w hich worked badly, bit reindeer, a new

dog will not w ork well, and vice versa” (Klokov - Yamal Peninsula field notes).

The principle o f “ self-teaching” in HDR com m unities applies not only to dogs,

but also includes reindeer. Thus, when answering questions about the teaching o f

reindeer, hunters and reindeer herders in Tofalaria often deliberately answered

simply: “ learning to use the pack is easy - laid them , tied and that is all” or

“saddled and rode” (K lokov - Tofalaria field notes). Through more detailed and

persistent interviews, it becam e clear that in fact the teaching o f a reindeer occurs

through efforts to ensure that it is docile or “tam e” . The main thing is to ensure

that reindeer are accustom ed to being on a leash, carrying cargo or riders on their

backs, and behaving calmly, without jum ping or attem pting to escape or loosen

their cargo. It is also im portant that taiga reindeer are not afraid o f hunting dogs.

The main m ethod o f such training is recurrently placing both anim als in physical

proxim ity to one another. This is accom plished by tying the deer and dog together

�272

Konstantin Klokov and Vladimir Davydov

in various different ways when they are not working. It should be noted that the

training and upbringing o f children in the families o f the nom adic peoples o f the

north is based on sim ilar principles o f im itation or mimesis. Children are not

forced to learn anything; they learn alone by im itating adults (W ulf 2001), and

this im itation plays an im portant role in hum an-anim al relations.

The connection between people, reindeer, and dogs is not only material, but

also em otional and spiritual. Thus, am ong reindeer herders, ethnographers note a

special type o f perception o f the surrounding world, tim e and space called “rein

deer thinking” - the ability o f people to perceive and to observe the world from

this anim al’s perspective (G olovnev et al. 2015: 16-17). Evenki hunters believe

that there is a special relationship between dogs and hum ans. It is even possible

com m unicate with dogs in dreams, and dogs are able to tell their m aster where

gam e m ay be found (Brandisauskas 2017: 201).

C o n c lu s io n

The relationships between hum ans and animals in H D R communities can be con

ceptualized as variable forms o f asymmetrical interdependence. O n the one hand,

people to a certain extent act as masters and organizers o f human-animal coop

erative activities. On the other hand, hum ans have to synchronize their daily and

seasonal rhythms with the needs o f their animals, upon which they are heavily reli

ant. In most northern Russian indigenous communities, the relationships between

humans and reindeer are paramount. For example, the needs o f reindeer heavily

influence the selection o f seasonal campsites and nomadic routes, as well as herd

ers’ daily sleep and rest schedules. Large numbers o f either reindeer or dogs cannot

be economically fed everywhere across the North. Large reindeer herds need vast

pastures rich in reindeer moss and with a chilly climate and the possibility o f migra

tion over long distances. This com bination o f ecological conditions can be observed

mainly in the tundra, and the Polar Census data clearly show that larger herds were

found in the tundra than in the taiga. Relatively small numbers o f dogs, perhaps

only 2 -3 individuals, are needed for hunting or for controlling even a large herd o f

reindeer. Larger numbers o f dogs are needed in settings where these animals are the

primary means o f transport. One needs an average o f 5-10 strong and obedient dogs

for one sled. People need fish or meat year-round to feed their dog teams, although

they mostly work only in winter. In winter, each dog needs around 1.5-2 kg o f fish

or m eat per day, while in summer they eat far less. To feed one team consisting o f

10 sled dogs for one year, one needs 3 -4 tons o f fish (Chikachev 2004: 18). Such

quantities o f protein m ay only be provided by households o f fishers and marine

hunters. A contributing factor is that the sea often throws ashore corpses o f walruses

and whales, whose m eat can help to feed a dog team for a few months.

Thus, the sym biosis o f hum ans, reindeer, and dogs in different types o f land

scapes was based on the use o f different types o f biological productivity provided

by natural ecosystems. In the m ainland tundra, the main com ponent o f the HDR

systems was large herds o f reindeer, consum ing plant resources - forage pasture

plants. Hum ans and pasture dogs (where they could be found) depended on rein

deer as the m ain source o f food, and, in the conditions o f the market, as income.

�Human-dog-reindeer communities in Siberia 273

In coastal landscapes, the dog was the m ain com panion o f hum ans, who used it

to harvest biological resources o f the aquatic ecosystems. Only in some areas, for

example, in the lower reaches o f the Yenisei River (Klokov 2000) and in the delta

o f the Ob River (Klolov - Yamal Peninsula field notes, 2013), sled dogs were

partially replaced by reindeer, which were used to transport fish caught for sale. It

is important to m ention that at these places reindeer were often fed on fish, which

was also eaten by people and dogs.

The com bination o f these two types o f HDR com m unities m ade it possible to

harvest the m axim um o f bio-resources in the continental and aquatic landscapes

o f the Arctic zone as a whole. In the Subarctic (in the taiga zone), the symbiosis o f

humans, reindeer, and dogs had a different structure. Here it was aim ed at collect

ing the m axim um result from hunting gam e animals: fur-bearing animals and wild

ungulates. Hum ans achieved this goal jointly with a riding reindeer and a hunting

dog. Thus, each o f these three m ain groups o f H D R systems was focused on the

use o f three different types o f biological productivity o f natural landscapes: plant

resources in the tundra and forest-tundra, fish and m arine m am m als in coastal

landscapes, and wild animals in the taiga.

The resilience o f such systems can be explained from the standpoint o f environ

m ental synergy. Reindeer can be considered as the central com ponent o f the HDR

community, since it is the only one o f the three who can live in the tundra and taiga

without the two other members. First o f all, the role o f hum ans is to stabilize such

systems. In natural conditions, three m ain factors regulate the num ber o f wild

reindeer populations: predators (m ost often, the wolf), diseases, and feed base.

H erders can at times weaken the effect o f these destabilizing factors by regulating

the num ber o f reindeer in their herds by increasing or decreasing the num ber o f

slaughtered anim als. Therefore, catastrophic fluctuations in the num bers o f wild

reindeer populations occur frequently but rarely in the case o f dom estic reindeer

(Syroechkovskii 1986: 150-156; Baskin 2009; 24-63). The reindeer herders’ dog,

unlike the wolf, affects the num ber o f reindeer indirectly, acting as an assistant to

a human, i.e. increasing his ability to m aintain the hom eostasis o f an HDR system.

A riding dog, acting partly as a com petitor o f a riding reindeer, also increases

hom eostasis, since a reindeer and a dog, if necessary, can partly replace each

other. To be m ore specific, the duplication o f systemic links increases the stability

o f the system. By helping humans, a hunting dog plays the role o f an am plifier

since it increases the efficiency o f the hunter’s work. W ith the help o f their dog

and reindeer friends, hum ans have managed to “tam e” the harsh landscapes o f the

Arctic and Subarctic regions, m aking them their home. For a man without a dog

and a reindeer, the northern environm ent has been and rem ains a hostile territory,

w hich can only be conquered with iron, gasoline, and electricity.

A c k n o w le d g m e n ts

This research was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (project No.

18-18-00309). Fieldwork in 2012-2016 was sponsored by the European Research

Council (project ADG 295458 Arctic Domus). The authors are especially grateful

to D avid Anderson, Rob Losey, Peter Loovers, Laura Siragusa, D m itry Arzyutov,

�274

and

Konstantin Klokov and Vladimir Davydov

C h a r le s

S te p a n o ff fo r

th e ir

c o m m e n ts

w h ic h

w ere

e s p e c ia lly

h e lp f u l

in

im p r o v in g th e m a n u s c r ip t o f th is c h a p te r .

Sources

F ie ld n o t e s : D a v y d o v - T a im y r P e n in s u la , 2 0 1 4 - 2 0 1 6 .

F ie ld n o te s : K lo k o v - T o fa la r ia , 2 0 1 3 , 2 0 1 4 (I r k u tsk r e g io n ( o b la s t') , E a s te r n S ib e r ia ).

F ie ld n o te s : K l o k o v - Y a m a l P e n in s u la , 2 0 1 3 .

F ie ld n o t e s : K lo k o v - C h u k o tk a , 2 0 1 6 .

R e fe r e n c e s

A n d e r s o n , D . G . ( e d . ) . 2 0 1 1 . T h e 1 9 2 6 /2 7 S o v ie t P o l a r C e n s u s E x p e d itio n s . O x f o r d a n d

N e w Y ork: B er g h a h n B o o k s .

A n d e r s o n , D . G . e t a l. 2 0 1 7 . A r c h it e c t u r e s o f d o m e s tic a t io n : O n e m p la c in g h u m a n -a n im a l

r e l a t i o n s in t h e N o r t h . J o u r n a l o f th e R o y a l A n th r o p o lo g ic a l I n s titu te 2 3 ( 2 ) , 3 9 8 - 4 1 6 .

B a s k i n , L . M . 2 0 0 9 . S e v e r n y i o le n

U p r a v l e n ie p o v e d e n i e m i p o p u li a ts y ia m i . O le n e v o d -

s tv o . O k h o ta . M o s c o w : T o v a r i s h c h e s t v o n a u c h n y k h i z d a n i i K M K .

B o g o s l o v s k a i a , L . S . ( e d .) . 2 0 1 1 . N a d e z h d a - g o n k a p o k r a iu z e m li. M o s c o w : I n s ti t u t N a s l e d i i a .

B r a n d i s a u s k a s , D . 2 0 1 7 . L e a v in g F o o tp r i n ts in th e T a ig a : L u c k , S p i r i ts a n d A m b i v a le n c e

A m o n g th e S ib e r ia n O r o c h e n R e in d e e r H e r d e r s a n d H u n te r s . N e w Y o r k : B e r g h a h n .

C h i k a c h e v , A . G . 2 0 0 4 . E z d o v o e s o b a k o v o d s tv o I a k u tii. I a k u t s k : I a F G U ‘ I z d a t e l ’s t v o S O

R A N ’.

C o p p i n g e r , R ., a n d M . F e i n s t e i n . 2 0 1 5 . H o w D o g s W o rk . C h i c a g o : U n i v e r s i t y o f C h i c a g o

P ress.

D a v y d o v , V . N . 2 0 1 4 . C o m in g B a c k to th e S a m e P la c e s : T h e E t h n o g r a p h y o f H u m a n R e i n d e e r R e l a t i o n s i n t h e N o r t h e r n B a i k a l R e g i o n . J o u r n a l o f E th n o lo g y a n d F o l k lo r -

is ti c s , 8 ( 2 ) , 7 - 3 2 .

G o l o v n e v , A . V ., Y e V . P e r e v a l o v a , I . V . A b r a m o v , D . A . K u k a n o v , A . S . R o g o v a , a n d

S . G . U s e n y u k . 2 0 1 5 . K o c h e v n ik iA r k ti k i : te k s to v o - v iz u a l' n y e m in ia ti u r y . E k a t e r i n b u r g :

A lp h a -P r in t .

K lo k o v , К . B . 2 0 0 0 . N e n e t s R e in d e e r H e r d e r s o n th e L o w e r Y e n is e i R iv e r : T r a d itio n a l

E conom y

U nder

C u r r e n t C o n d it io n s

and

R esp on ses

to

E c o n o m ic

C h an ge.

P o la r

R esea rch , 1 9 ( 1 ) , 3 9 - 4 7 .

K o z ’m i n , V . A . 2 0 0 3 . O le n e v o d c h e s k a ia k u l ’t u r a n a r o d o v Z a n a d n o i S ib ir i. S t. P e t e r s b u r g :

S a in t- P e te r s b u r g S ta t e U n iv e r s ity .

P o k h o z ia is tv e n n a ia p e r e p i s ’ P r ip o li a r n o g o S e v e r a S S S R 1 9 2 6 /2 7 g o d a . T e r r i to r ia l 'n y e i

g r u p p o v y e i to g i p o k h o z ia is t v e n n o i p e r e p i s i . 1 9 2 9 . M o s c o w : S t a t i z d a t T s S U S S S R .

S t e p a n o f f . C . 2 0 1 2 . H u m a n - A n i m a l ‘J o i n t C o m m i t m e n t ’ i n a R e i n d e e r H e r d i n g S y s t e m .

H A U : J o u r n a l o f E t h n o g r a p h ic T h e o r y , 2 ( 2 ) , 2 8 7 - 3 1 2 .

S te p a n o f f, C . 2 0 1 7 . T h e R is e o f R e in d e e r P a s t o r a lis m in N o r th e r n E u r a s ia : H u m a n a n d A n i

m a l M o t i v a t i o n s E n t a n g l e d . J o u r n a l o f R o y a l A n th r o p o lo g ic a l I n s titu te , 2 3 , 3 7 6 - 3 9 7 .

S y r o e c h k o v s k i i , E . E . 1 9 8 6 . S e v e r n y i o l e n ’. M o s c o w : A g r o p r o m i z d a t .

V a te , V . 2 0 0 5 . M a in t a in in g C o h e s io n T h r o u g h R itu a ls : C h u k c h i H e r d e r s a n d H u n te r s ; A

P e o p l e o f t h e S i b e r i a n A r c t i c . S e m i E t h n o lo g ic a l S tu d ie s , V o l . 6 9 . I n K . I k e y a a n d E .

F r a tk in ( E d .) , P a s t o r a l i s t s a n d T h e ir N e i g h b o r s in A s i a a n d A f r ic a . O s a k a : N a t i o n a l

M u s e u m o f E t h n o lo g y , 4 5 - 6 8 .

W u l f , K . 2 0 0 1 . A n th r o p o lo g ie d e r E r z ie h u n g . E in e E in f u h r u n g . W e i n h e i m a n d B a s e l : B e l t z .

�

Vladimir Davydov

Vladimir Davydov