CHAPTER 8

Copyright @ 2018. Routledge.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

Signifying Queerness

Literature and Visual Art

Susan K. Thomas and William J. Simmons

EBSCO : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 10/23/2018 10:42 AM via UNIV OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

AN: 1761971 ; Murphy, Michael John, Bjorngaard, Brytton.; Living Out Loud : An Introduction to LGBTQ History, Society, and Culture

Account: s8983984.main.ehost

263

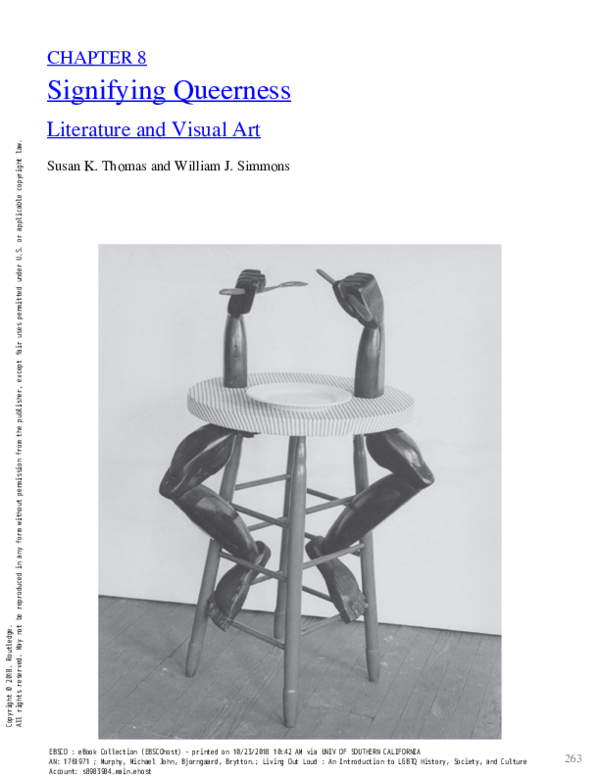

�Kate Millett, Dinner for One, 1967, mixed media. Source: Estate of Kate Millett.

rom the earliest recorded history, words and images have been essential vehicles for human

expression. Whether in the form of prehistoric fertility statuettes, Renaissance portraiture, modern

poetry, or contemporary novels, literature and the visual arts have offered a means to transform the

intangible into the tangible, which, in many ways, resembles LGBTQ experience. Through a focused

process of introspection and articulation, the creation of art and literature allows personal traits such as

gender identity and sexual orientation to be expressed and communicated to readers and viewers. But

beyond individual expression, art and literature may also capture and record a society’s collective

sensibility about gender and sexuality—including minority gender identities and same-sex

attractions—thus preserving it and making it available to future generations. As such, words and images

can represent important resources for understanding the global history of gender variance and same-sex

desire. The history of art and literature, alongside other forms of historical evidence, reveals that social

attitudes about gender variance and same-sex desire have changed over time, with some societies being

very accepting, even celebratory, while others being indifferent or repressive. It also shows that LGBTQ

writers and artists persevered even in the most inhospitable familial, communal, or societal environments.

Copyright @ 2018. Routledge.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

F

While it is not always possible to know if a writer or artist was same-sex attracted or gender variant, or

identified as gay or transgender, art and literary historians have identified many, many texts and images

with implicit or explicit themes of gender variance or same-sex desire. Some of these are now seen as

essential to LGBTQ history, even though they may not have been viewed that way by their makers, or in

the time or place where they were created. As such, it is not always easy to decide if such works or their

makers should be characterized as gender non-conforming, homosexual, gay, etc. What, exactly, comprises

LGBTQ history is a dynamic, evolving subject; so is the terminology used to describe it. This chapter is

written from the perspective of the present day and describes art and literature that is now considered part

of LGBTQ visual and literary history, therefore present-day terms are used to describe such works. The

first half of the chapter describes major works, themes, and creators in LGBTQ literary history, with an

emphasis on Europe and America, from antiquity through to the present day. The second half presents a

similar overview of LGBTQ visual arts, such as painting, sculpture, photography, and related media.

LITERATURE

There has not been a time that homoerotic literature has not existed beneath the larger umbrella of

literature. Authors have used the genres of poetry, mythology, and prose to subtly (and at times, not so

subtly) record their feelings and desires for same-sex lovers, or to live life as a different gender. Because of

the persecution or opposition in many world cultures throughout history, queer individuals have turned to

literature as a source of knowledge, validation, and comfort.

Ancient Mythology and Classic Literature

Themes of love between members of the same sex exist in a variety of ancient texts throughout the world,

drawing on heroic love between men who bond through the shared experience of battle. The affection

between men often emerges through homoerotic undertones in these early works. The Ancient Greeks, and

later the Romans, drew upon pederasty: romantic and sexual affection between older men and teenage

boys.

The oldest surviving story is an Ancient Sumerian epic poem about a historical king who ruled the

Mesopotamian city of Uruk in 2750 BCE. Written 1,000 years before Homer’s Iliad or the Bible,

Gilgamesh tells the story of a man who learns to temper his own emotions and actions, which turns him

EBSCO : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 10/23/2018 10:42 AM via UNIV OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

AN: 1761971 ; Murphy, Michael John, Bjorngaard, Brytton.; Living Out Loud : An Introduction to LGBTQ History, Society, and Culture

Account: s8983984.main.ehost

264

�Copyright @ 2018. Routledge.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

into a strong leader. The text also describes the friendship between the title character King Gilgamesh and

Enkidu, a wild man who is tamed by a temple priestess. Although the poem does not explicitly state that

Gilgamesh and Enkidu have a sexual relationship, the homoeroticism in the text is undeniable as the

priestess Nikun tells Gilgamesh that after meeting Enkidu, “You will take him in your arms, embrace and

caress him / The way a man caresses his wife” (Mitchell, 2004). While many literary critics have defined

the relationship as homoerotic, historically, the text would have been a reflection of heroic love, a deep

affection and respect between warriors.

Numerous mythologies and religious narratives include stories of romantic affection or sexuality

between men or between male gods and men. There are also instances of divine action that results in a

gender change. Critics often interpret these stories through a homoerotic lens, which may differ from the

original culture’s understanding of the stories. In classical mythology, the tradition of male lovers was

credited to ancient Greek gods and heroes such as Zeus, Apollo, Poseidon, and Heracles (with Ganymede,

Hyacinth, Nerites, and Hylas, respectively) to validate the tradition of pederasty, a same-sex relationship

between an adult male and a pubescent or adolescent male, based on the consent of the boy. Pederasty was

considered an educational institution in some cultures as the adult mentored the boy in that society’s moral

and cultural values (Freeman, 1999).

Although Homer (8th century BCE) did not portray the heroes Achilles and Patroclus as homosexual

lovers in the Iliad (8th century BCE), later ancient authors, such as Aeschylus, presented the relationship as

pederastic in The Myrmidons, writing of “our frequent kisses” and a “devout union of the thighs”

(Crompton, 2003). Plato does the same in his work Symposium (385–370 BCE); Phaedrus cites Aeschylus

and presents Achilles as an example of sacrificing oneself for a lover. Symposium also includes a creation

myth that explains homosexuality and heterosexuality, and celebrates the pederastic tradition and erotic

love between men (Woods, 1998).

The Sosias painter, Achilles Binding the Wounds of Patroclus, ca. 500 BCE, red-figure vase painting,

Altes Museum (Berlin, Germany). Source: Photo by Bibi Saint-Pol. Image courtesy of Wikimedia

Commons.

In the Symposium, Aristophanes tells the creation myth to describe why people say that they feel whole

EBSCO : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 10/23/2018 10:42 AM via UNIV OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

AN: 1761971 ; Murphy, Michael John, Bjorngaard, Brytton.; Living Out Loud : An Introduction to LGBTQ History, Society, and Culture

Account: s8983984.main.ehost

265

�Copyright @ 2018. Routledge.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

when they have found their true love. He explains that in primal times, people had double bodies that

looked like two people joined at the back, their faces and limbs turned away from each other. There were

three sexes: the all-male, the all-female, and the androgynous, who were half male, half female. The people

attempted to scale Olympus to set upon the gods. Zeus considered destroying them with thunderbolts, but

not wanting to deprive himself of their devotions and offerings, cut them in half, separating the two bodies

(Plato).

The tradition of pederasty in ancient Greece, and later the acceptance of limited homosexuality in

ancient Rome, created an awareness of same-sex attraction between men and sex in ancient poetry. In the

second of Virgil’s Eclogues (1st century BCE), the shepherd Corydon proclaims his love for the boy

Alexis. During the same century, some of Catullus’s erotic poetry is directed at other men and his “Carmen

16” is considered to be one of the earliest examples of explicit sex acts between men (Woods, 1998).

Sappho (630/612–570 BCE) was a Greek lyric poet born on the island of Lesbos. (Lyric poetry is poetry

meant to be read aloud accompanied by music played on a stringed instrument called a lyre.) Very little is

known about Sappho’s life, but her poetry was well-known and admired throughout much of antiquity.

Subjects in Sappho’s poetry vary. Some of her poems, such as “Fragment 16” and “Fragment 44,” are lyric

retellings of Homer epics (Rutherford, 1991). Several of her poems have themes of love, and would have

been written to be performed as wedding poems, intended to be sung to the bride when she entered the

nuptial chamber (Greene, 1996). Other poems appear to be odes from one woman to another, which has

caused discussion regarding Sappho’s sexuality and intentions within her work.

Group of Polygnotos, Sappho (seated) reads one of her poems to a group of three student-friends, ca.

440–430 BCE, red-figure vase painting, National Archaeological Museum (Athens, Greece), no. 1260.

Source: Photo by /CC BY-SA 2.5 license. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Sappho’s sexual desire, whether for men or for women, has been debated for centuries. Today, she is a

symbol of lesbianism and island where she lived (Lesbos) is the basis of the modern term lesbian.

However, this has not always been so. In classic Athenian comedy Sappho was caricatured as a

promiscuous heterosexual woman (Most, 1995). The first testimonia, or written documentation, that

EBSCO : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 10/23/2018 10:42 AM via UNIV OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

AN: 1761971 ; Murphy, Michael John, Bjorngaard, Brytton.; Living Out Loud : An Introduction to LGBTQ History, Society, and Culture

Account: s8983984.main.ehost

266

�discuss Sappho’s homoeroticism come from the Hellenistic period, but these ancient authors do not appear

to have believed that Sappho had sexual relationships with other women (Rayor & Lardinois, 2014).

Copyright @ 2018. Routledge.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

Homosexuality and Biblical Allusions

The Judeo-Christian Bible has been used to both denounce and defend homosexuality. There are passages

in the Old and New Testaments that appear to prohibit same-sex behavior, especially between men. Other

passages describing romantic affection and homoeroticism between men have been interpreted as

gay-themed and accepting of homosexuality.

In the latter half of the 20th century, scholars began to argue that the love between David and Jonathan

reached further than platonic friendship. The story of David and Jonathan focuses on the close friendship

that the two develop as youth after David has killed Goliath. “Now it came about when [David] had

finished speaking to Saul, that the soul of Jonathan was knit to the soul of David, and Jonathan loved him

as himself . . . Then Jonathan made a covenant with David because he loved him as himself” (1 Samuel 18,

New JPS Translation). The traditional and mainstream interpretation of the relationship between the two

men is platonic, an example of homosociality. The story of David and Jonathan is similar to that of

Gilgamesh and Enkidu. Both relationships are between heroic and powerful men. Gilgamesh and David

both have a love for the other man that is described as being stronger than that of a woman. Both Enkidu

and Jonathan have untimely deaths. And both friendships can be read as homoerotic because of the close

relationships that exist between the men as they put their love for each other above all else, even their love

for women.

Sodom and Gomorrah

The story of Sodom and Gomorrah is the best-known story in the Judeo-Christian Bible used to

condemn homosexuality. The word sodomy, taken from Sodom, was coined by an English

churchman to describe sex between men (Greenberg, 2004). The story is that God, knowing of the sin

in Sodom, sent two angels disguised as men to the righteous man Lot, who welcomed the men, fed

them and invited them to spend the night in his house. That night, the men of the city came to Lot’s

home and demanded he turn the visitors over to them so that they could have sex with them. Lot

refused and offered his two virgin daughters instead. The men of the city once again insisted that Lot

turn over his guests, but Lot again denied them. In the morning, the angels instructed Lot to take his

family and flee the city, for God was going to destroy Sodom in fire and brimstone for its sins. Lot’s

family was to take what they needed and flee to the hills without looking back. The family did as

instructed but, as they fled, Lot’s wife turned to look back at the destruction, only to be turned into a

pillar of salt (Genesis 19:1–26, Tanakh).

Although the common perception is that the sin of Sodom was homosexuality, Jewish literature

often rejects this reading (Greenberg, 2004). The text in the Book of Ezekiel cites Sodom’s

arrogance, and its inhospitality to both visitors and the poor, although the residents of the city had

plenty to share (Ezekiel 16:49). Rabbinical scholars who authored the Talmud, a Jewish commentary

on the oral Torah, describe the destruction of Sodom as the result of selfishness and an unwillingness

to share their wealth with travelers (Tosefta Sotah 3:11–12).

Some biblical scholars argue that the use of the word yada (know), which is often used in the

Hebrew bible to indicate carnal knowledge, reveals the intention of the men of Sodom to have

same-sex relations with the angels. Yada is used in Genesis when Adam knew Eve, meaning that they

had sexual intercourse (Genesis 4:1). If yada is translated as carnal knowledge, the implication is that

the men of the city planned to rape the angels, a violent act of aggression that condemns the men of

Sodom, not because it is same-sex rape, but because it is rape (Robinson, 2010). The rape of women

would have been as abhorrent as homosexual rape. Additionally, the word yada exists in the Hebrew

EBSCO : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 10/23/2018 10:42 AM via UNIV OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

AN: 1761971 ; Murphy, Michael John, Bjorngaard, Brytton.; Living Out Loud : An Introduction to LGBTQ History, Society, and Culture

Account: s8983984.main.ehost

267

�bible 900 times as meaning “to know” or “to interrogate,” while “to know” as a euphemism for

sexual intimacy is only used 13–14 times throughout the entire Hebrew scriptures (Hebrew frequency

list, 2016). If this is the case, the men of Sodom sinned through their intent to interrogate the angels

to learn their intentions and to avoid sharing personal wealth, which was inhospitable. Because Lot

offered his two virgin daughters to the crowd in place of the angels, the translation of the word yada

is more likely to be to know the angels sexually in the act of violent rape.

Copyright @ 2018. Routledge.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

Susan K. Thomas

The English Renaissance (15th–17th century CE)

The Renaissance was a cultural and artistic rebirth in Europe and England dating from the 14th century to

the early 17th century. This period is often considered a cultural bridge between the Middle Ages and

modern history. With the rediscovery of classical Greek philosophy, new thinking in Europe was reflected

in art, architecture, politics, science, and literature. These changes in culture and art were reflected in

England during the late 15th century. During the English Renaissance, gender divisions were substantial as

women were considered inferior to men, and held subservient roles. Women were unable to hold property,

and were expected to be under the safeguard of a male protector, either a husband or male family member,

even when going out. Cross-dressing gave a woman a protection and independence that she did not

otherwise possess by allowing her to leave the home and travel alone. However, cross-dressing was illegal

for both men and women, as the Judeo-Christian Bible labeled it as a sin. Clergy delivered sermons against

the practice during church services. The regulation of clothing produced and marked gender difference,

although other cultural shifts were occurring. In the theater, cross-dressing was a necessity as women were

not permitted to take the stage. Instead, young effeminate men often played the role of women. This was

not a statement, but a comic tradition—playwrights often included the comic tradition of cross-dressing in

their plays (Howard, 1988).

William Shakespeare (1564–1616) used the motif of cross-dressing as a subterfuge in seven of his plays

by disguising women as men, and in all seven of those plays crossdressing both complicates and resolves

the plot. This device creates a level of homoeroticism in the texts as the women often encounter their

unknowing lovers while disguised as men, only later to reveal their true identities. In As You Like It, the

character of Rosalind must disguise herself as a man, Ganymede, after being exiled from court. She flees

with her friend, and daughter of the king, Celia, who is now disguised as a poor woman, to the Arcadian

Forest of Arden, where they meet Orlando and his servant, Adam. Orlando is in love with Rosalind, and

therefore is saddened at her exile. Rosalind is also in love with Orlando and, disguised as Ganymede,

pretends to counsel Orlando to cure him of his love. Ganymede says that he will take Rosalind’s place, and

that he and Orlando can act out the relationship. Hilarity ensues when the young Phoebe falls in love with

Ganymede (Rosalind). Over the course of the play, Ganymede convinces Orlando to promise to marry

Rosalind. Ganymede then reveals himself as Rosalind to Orlando, and the two marry in the final scene of

the play. The gender reversals in the story are of particular interest because Rosalind, who in

Shakespeare’s day would have been played by a boy, finds it necessary to impersonate a boy, who is then

pursued by a young woman, who is played by a boy.

16th and 17th Century Europe

The period known as the Age of Enlightenment (1685–1815) permitted some challenge to traditional

doctrines of society in Western Europe. Developments in industry allowed the production of consumer

goods in greater quantities at lower prices, which encouraged the spread of books, pamphlets, and

newspapers (Outram, 1995). With an increase in the dissemination of the printed word, literacy increased

for both men and women (Darnton, 1985). In France, a waning of religious influence meant that the

amount of literature about science and art increased (Petitfils, 2005). And while books were often too

EBSCO : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 10/23/2018 10:42 AM via UNIV OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

AN: 1761971 ; Murphy, Michael John, Bjorngaard, Brytton.; Living Out Loud : An Introduction to LGBTQ History, Society, and Culture

Account: s8983984.main.ehost

268

�Copyright @ 2018. Routledge.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

expensive for most to buy, readers accessed books through state-run libraries or by purchasing cheaply

produced editions (Outram, 1995).

During this time, there was a renewed interest in the Classical era of Greece and Rome, allowing authors

to allude to Greek mythological characters or to place their stories in Ancient Greece, where pederasty was

common. Because the legal punishment for sodomy was death in some European countries and in England

(and its colonies), it was dangerous to publish literature with overtly homosexual themes, which could

result in an investigation of an author’s personal life, potentially ruining their reputation and eliminating

opportunities. Thus, authors often expressed homoerotic themes in coded language that only some readers

would understand. This permitted authors to escape prosecution for obscenity and further investigation.

Being too overt in writing would mean immediate suppression, as in the case of the text Alcibiades the

Schoolboy, a satirical Italian dialogue published anonymously in 1652. The text, a written defense of

homosexual sodomy and love between men, is set in ancient Athens. A teacher modeled after Socrates

desperately wants to consummate the relationship with his student Alcibiades. He uses all the tactics of

rhetoric and dishonesty at his disposal, arguing that Nature gave people sexual organs for their own

pleasure, and that it would insult her to use them otherwise. Upon its publication, Alcibiades was

suppressed for its explicit nature. Only ten copies of the text still survive. In 1888 an article revealed the

author as Antonio Rocco, an Italian priest and philosophy teacher (Dynes, 1990). Had Rocco been

discovered as the text’s author in 1652, he would have been prosecuted for obscenity and, at the very least,

imprisoned.

18th and 19th Century Europe and America

During the 18th and 19th centuries homosexual authors continued to protect themselves from prosecution

under overbearing obscenity laws through the coding of texts, but others protected themselves by writing

about heterosexual relationships through the woman’s perspective, as in the case of John Cleland’s

(1709–1789) novel Fanny Hill, published in 1749.

Published in two installments, the erotic novel Fanny Hill, or Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure is one of

the most prosecuted and banned books in history. Written as a series of letters between Frances “Fanny”

Hill, a former prostitute, and an unknown woman, it tells the story of Fanny’s youth as a young girl

coming to London and becoming a prostitute before marrying a man who does not care about her past. In

November 1749, Cleland, the publishers, and the printer were arrested on obscenity charges as a result of

the novel’s content. Although its uncensored version was officially pulled from circulation, illegal copies

were distributed, making Fanny Hill a best-selling novel until the 1970s (Sabor, 2004).

Cover of American edition of The Life and Adventures Miss Fanny Hill (ca. 1910). Source: Photo by

Chick Bowen, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

EBSCO : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 10/23/2018 10:42 AM via UNIV OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

AN: 1761971 ; Murphy, Michael John, Bjorngaard, Brytton.; Living Out Loud : An Introduction to LGBTQ History, Society, and Culture

Account: s8983984.main.ehost

269

�Copyright @ 2018. Routledge.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

Contemporary critics described Cleland’s novel as homoerotic due to the level of detail in Fanny’s

description of her sexual affairs, her obsession with penis size, and the two instances of homosexuality in

the text (Robinson, 2006). These, as well as Cleland’s lack of close friends and his unmarried status, have

added to the supposition that he was homosexual. Additionally, his bitter falling out with his friend

Thomas Cannon (1720–?), author of the 1749 pamphlet Ancient and Modern Pederasty Investigated and

Exemplify’d, the earliest published defense of homosexuality in English, also led to this speculation

regarding Cleland’s sexuality (Gladfelder, 2012). Although none of the pamphlets have survived, a partial

record of the contents exists in the publisher John Pulser’s 1750 indictment for his part in the publication

of the text. Cannon begins the pamphlet by half-heartedly denouncing the practice of pederasty

(Gladfelder, 2007). The balance comprises an anthology of ancient Greek and Roman texts, complete with

Cannon’s own commentary supporting pederasty and homosexuality. The obscenity charges brought

against Cannon were eventually dropped, and the pamphlet that brought such trouble has disappeared

almost into obscurity.

During the second half of the 18th century, Gothic fiction became popular in both England and America,

largely with female audiences, by combining horror, death, and at times romance. Homosexual authors of

Gothic fiction, such Matthew Lewis’s (1775–1818) The Monk (1795) and Charles Maturin’s (1782–1842)

The Fatal Revenge (1807), used one of Shakespeare’s techniques to create homoerotic texts—writing a

female character who disguises herself as a young man to gain access to the protagonist or to an all-male

world that is excluding her. This plot device enabled the author to create a subject who becomes infatuated

with a man, but permitted the author to safely avoid prosecution for obscenity through the reveal that the

young man in the text is actually a woman in disguise, with whom the protagonist then falls in love.

While the Gothic novel grew in popularity, the Romantic movement gained momentum at the end of the

18th century and continued into the early 19th century. Romantic literature—which could allow men to

express affection for each other in literature, often through the motif of ancient Greece and the use of

pederasty—was an acceptable medium for depicting such affection. In 1805 Augustus, Duke of

Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg (part of what is today Germany), published his novel A Year in Arcadia: Kyllenion,

the earliest known novel to focus on an explicitly homosexual male love affair (Haggerty, 1995). The

novel’s setting is ancient Greece, and focuses on several couples falling in love, including a homosexual

one (Béeche, 2013). Although the text is veiled as a close friendship, the homoeroticism is present, and

even some of Duke August’s contemporaries felt that his characters pushed the acceptable boundaries of

male affection in literature (Jones, 2015).

By the mid-19th century, literature in America was shifting between Transcendentalism (the

omnipresent existence of the divine in all nature and humanity) and Realism (the authentic representation

of reality). One of the best-known poets in American history, Walt Whitman (1819–1892), incorporated

both in his work. His most popular collection of poetry, Leaves of Grass, was first published in 1855. The

Calamus poems in Leaves of Grass celebrate and promote the “manly love of comrades” (Whitman, 1981

[1855]). Critics believe that these poems are Whitman’s clearest expression in print of same-sex desire and

attraction between men. He is believed to have had romantic and sexual relationships with several different

men in his lifetime, but the only descriptions are by men who claimed to have had relationships with him.

EBSCO : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 10/23/2018 10:42 AM via UNIV OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

AN: 1761971 ; Murphy, Michael John, Bjorngaard, Brytton.; Living Out Loud : An Introduction to LGBTQ History, Society, and Culture

Account: s8983984.main.ehost

270

�Copyright @ 2018. Routledge.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

M. P. Rice, Walt Whitman and his rebel soldier friend Peter Doyle (ca. 1869). Source: Bayley Collection,

Ohio Wesleyan University. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Many scholars believe that American poet Emily Dickinson (1830–1886) was a lesbian, pointing to her

relationship with sister-in-law Susan (Sue) Gilbert Dickinson. The poet lived much of her life as a recluse

in a home next door to Sue Dickinson’s home, allowing the two to see each other daily. Throughout their

friendship Sue was supportive of Emily, who considered her not only a beloved friend, but also an

influence, inspiration, and confidant (Martin, 2002b). Numerous poems and letters point to a close

friendship between the two women, and Emily may have been in love with Sue, but there is no indication

that the two had a romantic or sexual relationship.

In the later 19th century, Gothic fiction saw a resurgence with novels such as Sheridan Le Fanu’s

Carmilla (2009), Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890), and Bram Stoker’s Dracula. While

both Le Fanu and Stoker were heterosexual, both Carmilla and Dracula openly approach homosexuality

and homoeroticism, respectively. Critics have noted that Carmilla has influenced the portrayal of vampires

in later fiction through its use of same-sex sensuality. In one passage, the protagonist Laura describes a

night visitor from years before (Jøn, 2001). She describes the stranger’s pretty face as she kneels next to

the bed, her hands caressing her under the coverlet. The stranger moves into bed with her, comforting her.

After Laura falls asleep, she is suddenly wakened by the “sensation as if two needles ran into my breast

very deep at the same moment” (Le Fanu, 2009). What becomes notable about Carmilla is that Laura’s

predator is not a male vampire, but a female one, creating a level of homoeroticism that had not previously

existed in the Gothic genre.

A similar homoeroticism marks Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897) through Dracula’s pursuit of Jonathan

Harker. In the text Dracula, Jonathan Harker has fallen asleep in an area outside of the safety of his room

in Dracula’s lair. As three female vampires converge and prepare to take Harker, Dracula appears and

states firmly, “This man belongs to me!” (Stoker, 1997). Harker swoons and the scene ends. The following

morning, Harker wakes with his clothes folded by his bedside, presumably by Dracula, and the reader is

left to interpret what may have happened during their interaction. Other instances occur between the two

that contribute to the homoeroticism within the novel (Stoker, 1997).

EBSCO : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 10/23/2018 10:42 AM via UNIV OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

AN: 1761971 ; Murphy, Michael John, Bjorngaard, Brytton.; Living Out Loud : An Introduction to LGBTQ History, Society, and Culture

Account: s8983984.main.ehost

271

�Copyright @ 2018. Routledge.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

William C. North, Emily Dickinson (ca. 1846–47), daguerreotype. Source: Archives and Special

Collections, Amherst College (Amherst, Mass.). Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

EBSCO : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 10/23/2018 10:42 AM via UNIV OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

AN: 1761971 ; Murphy, Michael John, Bjorngaard, Brytton.; Living Out Loud : An Introduction to LGBTQ History, Society, and Culture

Account: s8983984.main.ehost

272

�Copyright @ 2018. Routledge.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

Napoleon Sarony, Oscar Wilde, ca. 1882, albumen print. Source: Library of Congress. Image courtesy of

Wikimedia Commons.

The intimacy of the vampire bite was further developed in the 20th century (Jøn, 2001). Homoerotic

undertones in vampire literature exist through to the present day, and some contemporary scholars believe

that people within the queer community identify strongly with vampires because the vampire’s

“experiences parallel those of the sexual outsider” (Keller, 2000). Vampires must be secretive, lest their

true identity and passions are revealed. There is also the constant fear of discovery (Dyer, 1988).

Irish author Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray was published in novel form in 1891 after being

published as a short story the previous year. The Gothic tale is the story of the title character, Dorian Gray,

who makes a deal with the devil to remain forever young while his portrait ages. Reviewers of the novel

criticized the text for its “decadence” and allusions to homosexuality (Ross, 2011). Although there is

nothing overtly homosexual in the novel, it is homoerotic. Dorian Gray is described by his beauty, a trait

often perceived as feminine. A homoerotic undertone surfaces when that beauty is recognized by other

EBSCO : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 10/23/2018 10:42 AM via UNIV OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

AN: 1761971 ; Murphy, Michael John, Bjorngaard, Brytton.; Living Out Loud : An Introduction to LGBTQ History, Society, and Culture

Account: s8983984.main.ehost

273

�Copyright @ 2018. Routledge.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

men. At the beginning of Dorian Gray, the artist Basil Hallward, paints Gray’s portrait. Hallward is

enamored of Gray’s beauty, finding in him his ultimate muse. Over the course of the novel, a span of 18

years, Gray indulges himself by experimenting with the vices he has read about in a French novel. The

implication is that these immoralities not only encompass alcohol and illicit drug use, but also sexual

encounters with both men and women.

Four years later, in 1895, Oscar Wilde was arrested and charged with “sodomy” and “gross indecency”

because of his affair with Lord Alfred Douglas, a younger man. Both men were found guilty and sentenced

to two years’ hard labor (Old Bailey Proceedings Online, 1895). The trial received worldwide attention,

and was a bitter reminder to those with same-sex attractions that not only was sodomy considered

unnatural, but that it was also a crime, although irregularly prosecuted.

Early 20th Century Europe and America

Gertrude Stein (1874–1946) was possibly the most famous lesbian author of the 20th century. Born in

Pennsylvania, Stein spent much of her adult life as an expatriate in Paris. Living with her brother Leo, the

two became avid collectors of modern art, and opened their home to avant-garde writers, authors, and

musicians. Stein’s sexuality was an open secret. She lived with her partner, Alice B. Toklas, from 1907

until Stein’s death in 1946. While together, the two had close friendships with many well-known artists

and authors, such as Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Ernest Hemingway, Thornton Wilder, and Sherwood

Anderson (Castle, 2003).

Much of Stein’s writing was radically innovative as it incorporated repetition and word-play. She gained

notoriety in the 1930s with the publication of The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, a memoir of Stein’s

early years in Paris. Several of her works had lesbian themes, including her short story “Miss Furr and

Miss Skeen” (1922), which, like much of Stein’s work, contains repetition and word-play throughout,

specifically the word “gay,” which is repeated at least 130 times. Stein was one of the first authors in the

20th century to use the word gay for homosexual, although it was a form of coding at that time since

heterosexual readers would understand it to mean carefree or happy (Castle, 2003).

A contemporary of Stein, Willa Cather (1873–1947), was an American author who later critics speculate

was lesbian. Many point to the years in her youth when she dressed in boy’s clothing, wore her hair short,

and preferred to be called William Cather, Jr. However, Cather understood that boys and men held special

privileges in the world, and she likely longed for those privileges, but by her second semester at university

Cather was dressing in women’s clothing. As an adult, her longest relationships were with women,

including Louise Pound, Isabelle McClung, and most notably, Edith Lewis, with whom Cather lived for 39

years. Literary scholars have identified homoeroticism, or same-sex desire, in two of Cather’s novels, One

of Ours (1922), which won the 1923 Pulitzer Prize in Literature, and Death Comes for the Archbishop

(1927). Both novels are told from a male protagonist’s point of view, which was uncommon for female

authors at the time. Both texts also contain close friendships between men that are affectionate, although

never sexual.

The Bloomsbury Group was an influential group of English writers, intellectuals, philosophers, and

artists that began in 1912. The ten core members were Clive Bell, Vanessa Bell, Roger Fry, Duncan Grant,

John Maynard Keynes, Desmond MacCarthy, Lytton Strachey, Leonard Woolf, and Virginia Woolf. The

group were united by a belief in the importance of the arts. Their works and philosophical ideas influenced

literature as well as modern attitudes toward feminism, pacifism, and sexuality. At least three of the men

identified as gay—Duncan Grant, E.M. Forster, and Lytton Strachey—though Forster remained closeted to

all but his close friends during his lifetime. Virginia Woolf (1882–1941) was the most famous of the

Bloomsbury Group, at least to contemporary audiences. While already married, Woolf embarked on an

affair with writer Vita Sackville-West in the early 1920s, which continued into the 1930s. In 1928 Woolf

presented Sackville-West with Orlando, a novel about a man whose life spans three centuries and both

sexes. Nigel Nicolson, Vita Sackville-West’s son, described the novel as “the longest and most charming

love letter in literature” (Blamires, 1983).

EBSCO : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 10/23/2018 10:42 AM via UNIV OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

AN: 1761971 ; Murphy, Michael John, Bjorngaard, Brytton.; Living Out Loud : An Introduction to LGBTQ History, Society, and Culture

Account: s8983984.main.ehost

274

�Copyright @ 2018. Routledge.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

British author Radclyffe Hall (1880–1942) was at the height of her career when she decided to write the

lesbian-themed novel The Well of Loneliness (1928). She was so determined that the text remain as she

intended that prior to its publication she told her editor that she required complete commitment from the

publisher as she would not allow even one word to be changed in the manuscript (Souhami, 1998). The

narrative of the novel follows Stephen Gordon, a woman whose parents are expecting a boy when she is

born, and christen her Stephen, which foreshadows her sexual identity. As she grows, Stephen develops

crushes; first on girls and, later, women. After her father’s untimely death, Stephen begins to dress in

masculine clothes and falls in love with Mary, a woman who returns her feelings. The novel ends tragically

when Stephen, who cannot keep her partner happy, pushes Mary into the arms of a man who has fallen in

love with her, hoping that one of them can live happily.

Richard Bruce Nugent, Dancing Figures, ca. 1935, black ink and graphite on paper, Brooklyn Museum

(New York, NY), acc. 2008.50.6. Source: Brooklyn Museum.

The Well of Loneliness was published July 1928 to mixed reviews. Some critics thought the text was

poorly structured. However, others praised the book for its sincerity and artistry. The book was the subject

of an obscenity trial that resulted in a determination that the book was obscene and should be destroyed

(Doan & Prosser, 2002). On appeal the verdict was upheld (Souhami, 1998). Initially, the novel faced the

EBSCO : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 10/23/2018 10:42 AM via UNIV OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

AN: 1761971 ; Murphy, Michael John, Bjorngaard, Brytton.; Living Out Loud : An Introduction to LGBTQ History, Society, and Culture

Account: s8983984.main.ehost

275

�Copyright @ 2018. Routledge.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

same outcome after its publication in the United States. In February 1929 courts deemed the book to be

immoral. However, upon remand to the New York Court of Special Sessions, the book was determined not

to be obscene (Taylor, 2001).

The Harlem Renaissance was a social, cultural, and artistic movement that began in the Harlem

neighborhood of New York City near the end of the World War I and lasted until the middle of the 1930s.

During this time it was known as the New Negro Movement, and was a resurgence of African-American

arts. Several noted writers of the Harlem Renaissance were known to be gay or bisexual, including Richard

Bruce Nugent (1906–1987), an openly gay writer and painter. His short story “Smoke, Lilies and Jade” in

the November 1926 issue of FIRE!! is thought to be the first short story to be published on the theme of

bisexuality. Contemporaries of Nugent during the Harlem Renaissance, Countee Cullen, Claude McKay,

and Langston Hughes, were all successful writers who were closeted about their sexual identities.

The novel Passing (1929) by Nella Larsen (1891–1964), written and published during the Harlem

Renaissance, has been recognized for its homoerotic subtext between the characters Irene and Clare

because of Irene’s appreciation of Clare’s beauty. Additionally, Irene and her husband Brian have a sexless

marriage and, while they do have children, they live as co-parents not as sexual partners (McDowell,

1986). The status of their marriage has caused both Irene and Brian to be interpreted as lesbian and gay

respectively. Irene labels Brian as queer, and he often expresses a desire to go to Brazil, a country

considered to be more tolerant of homosexuality in the 1920s. Both are considered indicators of Brian’s

sexuality. The text’s primary theme is racial passing, but the metaphor expands to multiple levels,

including sexual (Blackmore, 1992).

Pulp Fiction

During the same period as the Harlem Renaissance in the early 1930s, the number of publishing

houses catering to alternate texts began to expand. These presses published both heterosexual erotica

and gay and lesbian texts. To circumvent censorship and legal prosecution, the publishers were

cautious about how they marketed these publications. Panurge Press, founded by Esar Levine, was a

mail-order company specializing in limited editions of erotica—some of it focused on same-sex

desire and sexual activity. Although mail-order business made tracking a publisher more difficult,

Levine was arrested several times, and once spent six months in prison after bail was not granted

(Bronski, 2003).

These small publishers led the way for pulp fiction, the original novels published only in paperback

form. Pulps were labeled as such because of the cheap wood-pulp paper on which they were printed,

which was very economical for a small publishing house. The name became synonymous for books

with eye-catching, often erotically suggestive, covers. Pulps were released in a variety of genres that

included thrillers, romances, crime noir, westerns, science fiction, and horror. In the 1950s a larger

number of lesbian-themed pulp novels were published than gay-themed pulps. These texts were often

written by men and had an audience of both lesbians and straight men. The gay-themed texts were

often considered more literary and less commercial than the lesbian publications (Bronski, 2003).

Tereska Torres’s Women’s Barracks, published in 1950, was the first pulp paperback to address a

lesbian relationship. The book was a fictionalization of Torres’s real-life experiences in the Free

French Forces in London during World War II. The book sold four million copies and was selected

by the House Select Committee on Current Pornographic Materials in 1952 as an example of how

paperback books were promoting moral indecency. As a result, the Committee began to require

publishers to conform to specific moral standards in the content and publicizing of books, or else face

fines or imprisonment. While this initially affected how authors framed their work in pulp fiction, as

the decade advanced publishers became bolder in printing material that might be deemed immoral

(Stryker, 2001).

By the 1960s more gay-themed than lesbian-themed pulp novels were being published. Beginning

EBSCO : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 10/23/2018 10:42 AM via UNIV OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

AN: 1761971 ; Murphy, Michael John, Bjorngaard, Brytton.; Living Out Loud : An Introduction to LGBTQ History, Society, and Culture

Account: s8983984.main.ehost

276

�in 1957, obscenity laws began to change, allowing for more obviously gay material to be published

without being prosecuted as obscene (Gunn and Harker, 2013). A number of renowned and respected

gay authors began their careers writing for pulp fiction, such as Tennessee Williams, Gore Vidal, and

Truman Capote (Stryker, 2001).

Copyright @ 2018. Routledge.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

Susan K. Thomas

Post-World War II

Following World War II, more same-sex themed books were reaching bookshelves than ever before.

American author Gore Vidal published The City and the Pillar in January 1948. The text is significant for

being the first post-World War II text that has an openly gay character who is content and does not die

tragically at the end of the novel (Stryker, 2001). Vidal also wrote the protagonist Jim to be an athletic,

masculine man. The author was determined to challenge stereotypes of the gay man as a transvestite,

lonely and bookish, or effeminate. He was determined to write the character as authentic and real (Vidal,

1995, xiii). Vidal was also very direct in his approach to the protagonist Jim’s sexuality in the novel. The

title of the text harkens back to the story of Sodom and Gomorrah, when Lot’s wife turns to look back at

the burning Sodom and is turned into a pillar of salt. Throughout Vidal’s novel Jim is unable to stop

thinking of a sexual encounter he had with his best friend, Bob, in high school. Jim’s obsession with that

encounter metaphorically freezes him so that he is unable to move on, resulting in disastrous consequences

at the end of the text. Upon the release of The City and the Pillar, The New York Times refused to review

the book, and every major newspaper or magazine refused to review any of Vidal’s novels for the next six

years (Vidal, 1995, xvi). The publication of the text was significant and led the way for the release of other

gay-themed texts by authors such as Truman Capote and Charles Jackson.

In the same month as The City and The Pillar, Random House published Truman Capote’s Other

Voices, Other Rooms. The novel is in the style of the Southern Gothic, which uses common themes of

deeply flawed, disturbing, or eccentric characters that may dabble in the occult, have ambivalent gender

roles, are placed in decayed or derelict settings, grotesque situations, and other sinister events that often

stem from poverty, alienation, crime, or violence (Merkel, 2008; Bloom, 2009). Other Voices, Other

Rooms, while including openly gay characters differs from The City and The Pillar in that it does not

include sex between men. This difference may explain the positive response to Capote’s novel even before

its publication.

Lesbian author Patricia Highsmith (1921–1995) published her second novel, The Price of Salt, in 1952;

a story about the beginnings of a lesbian relationship in New York City in the 1940s. The book was

initially published under the pseudonym Claire Morgan, as Highsmith feared that she would be forever

labeled a lesbian author, which would overshadow her writing. The novel was considered groundbreaking

for its time because of Highsmith’s choice to end the novel with a happy ending, and for departing from

the stereotypical characterization of lesbians (Carlston, 2015). Highsmith did not acknowledge authorship

until the 1990 Bloomsbury re-release, retitled Carol. A film adaptation of Carol was released in 2015.

Highsmith’s novels The Talented Mr. Ripley (1955) and Small g: A Summer Idyll (1995) are also gay

themed. The latter also mentions HIV, but not as a significant element in the plot or character

development.

During the 1940s gay playwright Tennessee Williams (1911–1983) suddenly earned fame with The

Glass Menagerie (1944). Critics consider Williams among the three foremost playwrights of 20th-century

American drama, along with Eugene O’Neill and Arthur Miller (Bloom, 2009). Williams received the

Pulitzer Prize for Drama for two of his plays, A Streetcar Named Desire (1947) in 1948 and Cat on a Hot

Tin Roof (1955) in 1955. Both texts include references to Williams’ life, including homosexuality, mental

instability, and alcoholism, and both would be made into highly successful Hollywood films.

During this same period James Baldwin (1924–1987) published his second novel, Giovanni’s Room,

which had explicit gay and bisexual themes. Baldwin’s first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953),

EBSCO : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 10/23/2018 10:42 AM via UNIV OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

AN: 1761971 ; Murphy, Michael John, Bjorngaard, Brytton.; Living Out Loud : An Introduction to LGBTQ History, Society, and Culture

Account: s8983984.main.ehost

277

�Copyright @ 2018. Routledge.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

which had a very subtle bisexual undercurrent, was widely accepted by African Americans, and Baldwin

was considered the voice of a new generation. After reading Giovanni’s Room, Baldwin’s editor

encouraged the author to burn the manuscript, arguing that a publisher would never be willing to accept a

book with such an openly gay storyline, and that Baldwin’s fans would never condone such a text. Critics,

while not pleased with the explicit homosexuality in the text, were much kinder than anticipated (Levin,

1991). By 1963 Baldwin could publish the bisexual-themed novel Another Country with little issue.

Cover of The Price of Salt by Claire Morgan (pseudonym of Patricia Highsmith) (Bantam Books, 1953).

Painting by Barye Phillips. Source: Bantam Books/Penguin Random House.

Also during the 1950s, the Beat Generation was emerging in San Francisco. The central themes of the

Beat culture are rejection of standard narrative values, the spiritual quest, exploration of American and

Eastern religions, rejection of materialism, experimentation with psychedelic drugs, and sexual liberation

and exploration (Charters, 2001). Among the best-known pieces of literature are Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl”

(1956), William S. Burroughs’s Naked Lunch (1959), and Jack Kerouac’s (1922–1969) On the Road

(1957). Both Ginsberg and Burroughs identified as gay, and Kerouac engaged in same-sex relations during

his life. “Howl” and Naked Lunch also became the focus of obscenity trials that ultimately helped to

change obscenity laws in the United States (Charters, 2001; Morgan, 1988).

The poem “Howl” was written in 1955 and published in Allen Ginsberg’s (1926–1997) collection Howl

and Other Poems in 1956. “Howl” was considered controversial because of its numerous references to

illicit drugs and sexual practices, both heterosexual and homosexual. At this time, a number of books that

discussed sex were being banned, including Lady Chatterley’s Lover (Raskin, 2004). Ginsberg’s use of

explicit language led to a trial on First Amendment issues after the publisher of the piece was brought up

on charges for publishing pornography. The judge in the trial dismissed the charges, determining that the

poem carried “redeeming social importance,” thus setting an important legal precedent (Morgan, 2006).

William S. Burroughs’ (1914–1997) Naked Lunch (1959) is a series of loosely connected vignettes that

Burroughs said could be read in any order. The protagonist, William Lee, is a drug addict modeled after

Burroughs, who was addicted to heroin, morphine, and several other drugs. The book was considered

controversial for both its erotic subject matter and its harsh language, which Burroughs recognized and

intended. The book was banned in Boston in 1962 for obscenity, but the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial

Court reversed that decision (de Grazia, 1998). The Appeals Court found that the book did not violate

obscenity statutes because it was believed to have some social value (Maynard & Miles, 1965).

The 1960s was a tumultuous period for the queer community, but with changing obscenity laws lesbian

and gay authors could now publish without prosecution and were able to bring attention to the oppression

faced by people in that community. Notably, Christopher Isherwood (1904–1986) published A Single Man

(1964), which demonstrated the oppression that lesbian and gay people face. The protagonist loses his

EBSCO : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 10/23/2018 10:42 AM via UNIV OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

AN: 1761971 ; Murphy, Michael John, Bjorngaard, Brytton.; Living Out Loud : An Introduction to LGBTQ History, Society, and Culture

Account: s8983984.main.ehost

278

�Copyright @ 2018. Routledge.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

partner in a tragic car accident but is then shut out by his deceased lover’s family and discouraged from

attending the funeral, although the two had been together for years. A Single Man presents homosexuality

as a human characteristic that deserves to be recognized and respected (Summers, 2015).

Carl Van Vechten, Portrait of James Baldwin, Sept. 13, 1955, silver gelatin photographic print. Source:

Courtesy of Van Vechten Collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Post-Stonewall: 1970 and After

Following the 1969 Stonewall Riots, sexual minorities, now often publicly identifying as bisexual, gay,

and lesbian enjoyed a renewed visibility in U.S. society and mass media. Anything seemed possible as

activist organizations were founded across the country in cities and on college campuses. This push in

equal rights for lesbian and gay people was reflected in an increase in publications. With the shift in

politics and obscenity laws, authors became even bolder in their texts, writing about openly affectionate

same-sex characters. Lesbians often found it easier to publish than gay men during this period. Isabel

Miller’s Patience & Sarah (1971; the pen name of Alma Routsong, 1924–1996), Rita Mae Brown’s

Rubyfruit Jungle (1973), and Rosa Guy’s (b. 1922) Ruby (1976) were published during the decade along

with others. One of the common themes in 1970s lesbian and gay literature continued to be the lack of a

happy ending, as in Brown’s Rubyfruit Jungle when the protagonist moves to New York City to attend

EBSCO : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 10/23/2018 10:42 AM via UNIV OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

AN: 1761971 ; Murphy, Michael John, Bjorngaard, Brytton.; Living Out Loud : An Introduction to LGBTQ History, Society, and Culture

Account: s8983984.main.ehost

279

�school and is forced to realize that, within the city, rubyfruit jungle (a metaphor for women’s genitalia) is

not as delicious or as varied as she had dreamed.

Copyright @ 2018. Routledge.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

The Combahee River Collective Statement

The Combahee River Collective (CRC) was founded in 1974 in an attempt to create a feminist space

for black women that also considered the intersectionality of class and sexuality (Marable and Leith,

516). While many African Americans belonged to and supported the National Organization of

Women (NOW), its goals focused on improving the economic situation of middle- and

upper-middle-class women (Harris, 2001). While many white women sought to leave the home to

join the workforce, many black women had been required to work outside of their homes to support

their families for decades.

The CRC began as the Boston chapter of the National Black Feminist Organization (NBFO), a

black feminist organization that focused more closely on issues affecting black women. However, the

members in the Boston chapter of NBFO were “more preoccupied with issues of sexual orientation

and economic development” (Harris, 2001) than the main chapter of NBFO, which “aimed their

activities at the more personal and practical level rather than at the political mainstream” (Harris,

2001). The Boston chapter, which became the Combahee River Collective, “came to define itself as

anti-capitalist, socialist, and revolutionary” (Harris, 2001). Lesbian author and activist Barbara Smith

wrote the statement with Demita Frazier and Beverly Smith, who divided the statement into four

chapters: The Genesis of Contemporary Black Feminism; What We [CRC] Believe; Problems in

Organizing Black Feminists; and Black Feminist Issues and Projects. Since the statement’s

publication and distribution, it has become a key influence on black feminism and on social theory

about race.

Susan K. Thomas

The late 1970s also saw some of the most provocative literature written by gay men to date. Larry

Kramer’s (b. 1935) Faggots (1978) and Andrew Holleran’s (b. 1944) Dancer from the Dance (1978)

signaled a change in writing that was free from legal censorship. Both Kramer’s and Holloran’s novels

focus on the gay party scene in New York City and on Fire Island, a summer resort destination near New

York City. Kramer’s text is a harsh parody of the casual sex and drugs that existed during the late 1970s as

the protagonist attempts to find love in a culture that seems to emphasize casual sexual encounters. The

book is sexually explicit in a way that would have led to its suppression just 15 years earlier.

Andrew Halloran’s Dancer from the Dance is also the story of young men searching for love in an urban

gay culture that emphasizes casual sex, partying, and drug use. Although Halloran’s novel also exposes

outsiders to certain parts of gay male culture in 1970s New York City and Fire Island, it is often

considered to be less bitter than Kramer’s novel. Instead, the book has been praised for its vivid imagery

and lush language. Both texts are significant because of their authors’ bold and explicit writing and their

critiques of the gay community.

The 1980s

The surge of publications in the 1970s continued into the 1980s, especially from women authors.

African-American novelist Alice Walker’s (b. 1944) 1982 novel The Color Purple won the 1983 Pulitzer

Prize for Fiction and the 1983 National Book Award for Fiction. The epistolary novel is the coming of age

story of a young African-American woman in rural Georgia, beginning in the 1930s. Young Celie is

married off to an older widower who is both verbally and physically abusive. Through the course of the

EBSCO : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 10/23/2018 10:42 AM via UNIV OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

AN: 1761971 ; Murphy, Michael John, Bjorngaard, Brytton.; Living Out Loud : An Introduction to LGBTQ History, Society, and Culture

Account: s8983984.main.ehost

280

�Copyright @ 2018. Routledge.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

texts, Celie finds love with another woman, who helps Celie discover her own voice for the first time in

her life. The novel’s themes focus on the sisterhood of women, racism, and gender roles. The Color Purple

has been listed as one of the 100 Most Frequently Banned Books by the American Library Association

because of racism, harsh language, violence, physical abuse, and sexual content (100 notable books of the

year, 2006). Although Walker has never made a public statement about sexual identification she has been

romantically involved with both men and women.

During the 1970s and 1980s author Audre Lorde (1934–1992) published some of the most influential

work in the women’s rights movement as she examined the intersections of gender, race, and sexual

identity. Her poetry expressed anger and outrage at civil and social injustices that she had observed and

experienced throughout her life. Her best-known texts today are Zami: A New Spelling of My Name

(1983), an autobiographical text, and Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (1984), a collection of Lorde’s

writings that draw upon her personal experiences of oppression, including sexism, heterosexism, racism,

classism, and ageism.

The impact of HIV/AIDS on gay and bisexual men caused a shift in the content of literature during the

late 1980s and the 1990s. Stories about the search for sex and love, and acceptance of one’s sexual

identity, gave way to tales of grief, loss, and survival in a time of political and social indifference to the

HIV/AIDS epidemic. Numerous novels and memoirs were published in the 1980s and 1990s about the

impact of HIV/AIDS on gay men. The earliest novels to mention the illness are Dorothy Bryant’s A Day in

San Francisco (1983) and Armistead Maupin’s Baby Cakes (1984). However, Paul Reed’s Facing It (1984)

is often considered the first AIDS novel because the theme of the text is the epidemic, while Bryant’s and

Maupin’s novels peripherally address the disease, which is present and affects the novel’s characters, but is

not the subject of the text (Reed, 1993).

Numerous memoirs also emerged from the 1980s and 1990s AIDS epidemics, documenting real-life

witnessing of the disease from those who loved those living with and dying from AIDS. Paul Monette’s

Borrowed Time: An AIDS Memoir (1988) chronicles his partner Roger Horwitz’s fight against and

eventual death from AIDS. Abraham Verghese’s My Own Country: A Doctor’s Story (1994) traces

Verghese’s experience as a young infectious-disease physician in the mid-1980s in Johnson City,

Tennessee, who begins to treat patients with the then-unknown disease. Out of necessity Verghese became

the town’s AIDS expert, and was often the only one at his patients’ bedsides as they were abandoned by

family and friends who were fearful or in denial. By the late 1990s more heterosexual-identified authors

were including the theme of AIDS in their work, such as in Michael Cunningham’s Pulitzer Prize winning

novel The Hours (1999), whose character Richard Brown is dying of AIDS, and who is also the small

thread tying much of the novel together.

EBSCO : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 10/23/2018 10:42 AM via UNIV OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

AN: 1761971 ; Murphy, Michael John, Bjorngaard, Brytton.; Living Out Loud : An Introduction to LGBTQ History, Society, and Culture

Account: s8983984.main.ehost

281

�Copyright @ 2018. Routledge.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

K. Kendall, Audre Lorde (Austin, TX, 1980), digital scan of a silver gelatin print. Source: Photo by K.

Kendall/CC BY 2.0 license. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The 1990s

The number and kind of publications by or about gender and sexual minorities increased even further in

the 1990s, expanding into the genres of romance, science fiction, and fantasy as many queer and allied

authors published books with LGBTQ protagonists by large genre publishers throughout the decade.

Melissa Scott’s novels Trouble and Her Friends (1994), Point of Hopes (1995), co-written with Lisa

Barnett, and Shadow Man (1995) explore ideas about sexuality and gender. Trouble and Her Friends was

an early cyberpunk novel to feature a queer protagonist, while Shadow Man moved beyond the gender

binary of male/female. Other authors, such as Rachel Pollack, Richard Bowes, Anne Harris, and Nicola

Griffiths, created worlds in which queer protagonists were not only common, but also flourished.

Octavia E. Butler (1947–2006) is one of the best-known lesbian science fiction authors of the 20th and

early 21st centuries. As an African American woman, one of her common themes was the intersection of

cultures that often resulted in cross-species relationships and flexible views of sexuality and gender. In her

novel Fledgling (2005), Butler writes of the vampiric Ina species and their emotional and sexual

EBSCO : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 10/23/2018 10:42 AM via UNIV OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

AN: 1761971 ; Murphy, Michael John, Bjorngaard, Brytton.; Living Out Loud : An Introduction to LGBTQ History, Society, and Culture

Account: s8983984.main.ehost

282

�Copyright @ 2018. Routledge.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

relationships with humans, both men and women. Butler also explores the intersection of species as the

protagonist is 53-year-old Shori, who is part Ina and part human, and sexual relationships with humans

(Nayar, 2011). These relationships are polyamorous, as the Ina are the primary partner of several male and

female humans, who willingly allow the Ina to feed from them (Shaviro, 2013).

The science fiction novel The Left Hand of Darkness (1969), written by Ursula K. Le Guin (b. 1929),

became immensely popular in 1970, winning both the Hugo and Nebula Awards for Best Novel (1970

Hugo awards; SFFWA, [n.d.]). The irrelevance of gender is one of the prominent themes in the text. Le

Guin chose to eliminate gender “to find out what was left” (Cummins, 1990). This theme is most

recognizable through the character Genly Ai, who begins the novel as masculine, but becomes more

androgynous over the course of the novel as he becomes more patient and caring, and less rigidly

rationalist (Cummins, 1990). In the novel, Ai visits the Gethen system, whose inhabitants are androgynous,

a tactic that the author uses to examine gender relations in human society. In the Gethen culture, Ai is

considered an oddity for his masculinity, which appears aggressive in relation to the passivity of the

Gethenians (Reid, 2009). Ai is only able to bond with the Gethenians, primarily the character of Estraven,

once he can accept the Gethenian’s gender ambiguity. Some feminist theorists have criticized the novel for

what they interpret as homophobia in the relationship between Estraven and Ai. There is an implied

attraction between the two characters, but that aspect of their relationship is never physically explored. In a

1986 essay Le Guin acknowledged and apologized for the fact that the novel had presented heterosexuality

as the norm on Gethen (White, 1999).

Leslie Feinberg (1949–2014), a transgender author and activist, wrote a handful of significant novels on

themes of sexual orientation, gender non-conformity, and transgender politics. The groundbreaking 1993

novel Stone Butch Blues won both a Lambda Literary Award and an American Library Association Gay &

Lesbian Book Award. The coming of age novel tells the story of Jess Goldberg, whose androgyny as a

child creates problems for both her and her parents, and as she grows, she has difficulties fitting in.

Throughout the book Jess discovers and accepts her gender differences and finally finds a voice to speak

out against oppression. Stone Butch Blues was the first known novel published by a person identifying as

transgender. In 2006 Feinberg published a second novel, Drag King Blues, which also had transgender and

gay themes. Additionally, Feinberg published several non-fiction books about transgender issues,

including Transgender Liberation: A Movement Whose Time Has Come (1992) and Trans Liberation:

Beyond Pink or Blue (1999).

21st Century

In the new millennium, LGBTQ themes and writers are appearing in more and more literary genres.

Authors incorporate positive portrayals of LGBTQ protagonists into numerous genres, from romance, to

historical fiction, to vampire detective fiction. Authors have also expanded into the graphic memoir,

comics, and children’s and young adult literature.

Lesbian cartoonist Alison Bechdel (b. 1960) was initially best known for her comic strip Dykes to

Watch Out For, which ran from 1983 to 2008 and is one of the earliest ongoing depictions of lesbians in

popular culture. However, Bechdel gained critical and commercial success in 2006 with the publication of

her graphic memoir, Fun Home. The book chronicles her childhood and the years before and after her

father’s suspected suicide. The text focuses primarily on her relationship with her parents, especially her

father, who Bechdel theorizes was also gay. Fun Home was named one of the top books of 2006 by The

New York Times (100 notable books of the year, 2006), The Times of London (Gatti, 2006), and

Publishers Weekly (The first annual PW comics week critic’s poll, 2006). Time magazine named the book

one of its top ten picks for 2006 (Grossman, 2007).

The late 20th and early 21st centuries have seen the publication of numerous memoirs and novels

focused on gender identity. Trans author Kate Bornstein’s Gender Outlaw: On Men, Women, and the Rest

of Us (1994) describes hir transition from living as a man to a woman (Bornstein prefers the gender-neutral

pronouns ze/hir). Following her medical and social transition to live as a woman, Bornstein realized that

EBSCO : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 10/23/2018 10:42 AM via UNIV OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

AN: 1761971 ; Murphy, Michael John, Bjorngaard, Brytton.; Living Out Loud : An Introduction to LGBTQ History, Society, and Culture

Account: s8983984.main.ehost

283

�Copyright @ 2018. Routledge.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

she still did not feel like she fit in, and realized that choosing a gender reflected society’s gender binary,

which requires people to identify according to the two available genders (Bornstein, 1994). She has since

stated that she does not call herself a woman, and she knows that she is not a man (Bornstein, 2012). Trans

activists Jennifer Finney Boylan and Janet Mock have both released memoirs describing their gender

transitions and their work to expand the gender binary through their activism.

Lane Rasberry, Kate Bornstein at Babeland, Seattle, WA, December 6, 2010. Source: Wikimedia

Commons.

In 2007 Jeffrey Eugenides published the novel Middlesex, a coming of age story about Calliope

“Callie/Cal” Stephanides, an intersex person who is assigned female at birth. Callie is raised as a girl and is

attracted to other girls. She only learns she is intersex after an accident, when tests determine that she has

5-Alpha Reductase Deficiency (5-ARD), a genetic condition that causes a genetically male-typical person

to be born with genitals that appear to be female-typical. Although Callie was born with female genitalia,

she also has male gonads, including internal testicles. Nature versus nurture and gender identity, and

intersex status are two themes within the novel. Although raised as a girl, Cal quickly renounces his female

gender upon learning he could have been raised a boy. In 2003, Middlesex was awarded the Pulitzer Prize

for fiction (Fischer & Fischer, 2007).

Children’s and Young Adult Literature

Authors began publishing children’s books with lesbian and gay themes in the 1980s. The first known gay

storybook is Jenny Lives with Eric and Martin by Susanne Bösche, published in Denmark in 1981 and in

England in 1983. The plot describes a few days in the life of Jenny, a five-year-old who lives with her

father, Eric, and his boyfriend Martin. The book covers small stories such as Jenny, Eric, and Martin doing

laundry together, and the preparation for a birthday party for Eric. Bösche explains that she wrote the book

to help children recognize different family forms (Bösche, 2000). Similarly, Lesléa Newman (b. 1955)

wrote Heather Has Two Mommies (1989) after speaking with a lesbian couple she knew with a child who

commented that they could not find any children’s books that reflected their family. The book is about a

child, Heather, who is raised by her lesbian parents, Jane and Kate. The family unit is discussed simply and

positively, as are other family situations in the book. Both Jenny Lives with Eric and Martin and Heather

Has Two Mommies met with controversy upon publication, being both regulated in libraries and pulled

from bookshelves. The American Library Association ranked Heather as the ninth most frequently

challenged book in the United Stated during the 1990s (100 notable books of the year, 2016).

Since the 1980s, numerous LGBTQ storybooks have been published for children that reflect varying

families and personal identities. Maurice Sendak’s (1928–2012) We Are All in the Dumps with Jack and

Guy (1993), Jeanne Arnold’s Amy Asks a Question: Grandma, What’s a Lesbian? (1996), Peter Parnell

and Justin Richardson’s And Tango Makes Three (2005), and Lesléa Newman’s Mommy, Mama, and Me

(2009) are just some of the titles that have been released about differing family forms. Other books have

been published that reflect a diversity of gender and sexual identities, such as Linda de Haan and Stern

Nijland’s King and King (2003), Christine Baldacchino’s Morris Micklewhite and the Tangerine Dress

(2014), and Jazz Jennings’s I am Jazz (2014).

The genre of young adult fiction has expanded immensely since the 1997 publication of J.K. Rowling’s

EBSCO : eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) - printed on 10/23/2018 10:42 AM via UNIV OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

AN: 1761971 ; Murphy, Michael John, Bjorngaard, Brytton.; Living Out Loud : An Introduction to LGBTQ History, Society, and Culture

Account: s8983984.main.ehost

284

�Copyright @ 2018. Routledge.

All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. The popularity of the Harry Potter series has inspired a new

generation of readers as well as authors, who have released a variety of fiction in different genres from

fantasy, to mystery fiction, to graphic novels. While the 20th century saw an increase in young adult

fiction, hundreds of young adult LGBTQ novels have been published since 2000. While numerous texts