Introduction to the special issue: Normativity

Pre-print version

A slightly modified version of this article has been accepted for publication in Journal of critical

Realism, published by Taylor & Francis.

Leigh Price

Rhodes University, South Africa

Background to the Special Issue

In this special issue of Journal of Critical Realism (JCR), I am delighted to present a wide-ranging

collection of papers by imminent critical realists on the subject of normativity. Also included in the

collection is a paper by Zachary Wehrwein, an American Pragmatist, who has joined the lively

response to Dave Elder-Vass’s argument against moral realism. The topic of normativity was chosen

because of its role in questions about the future of humanity, possibly influencing whether the

human species will survive at all. For instance, without normative acknowledgement of the

anthropogenic causes of climate change, it is difficult to take action to reduce carbon emissions.

Although Roy Bhaskar’s original objective for critical realism was to revindicate ontology, in 2007, he

issued a corrective to this, and stated that it is also necessary to consider ontology from the point of

view of living in a better world; and that this requires epistemology, since we need to find out what

would be necessary to achieve such progress. He therefore argued that:

‘Although ontology is important, we also have to pay attention to other features of the

intellectual landscape, including epistemology and issues to do with judgemental rationality

- issues that have been of secondary importance for critical realists until recently.’

(Bhaskar 2007, 192)

The Special Issue considers how to make the world a better place

In discussing normativity, one must assume not only that there is a way of determining, however

fallibly and contingently, what a better world might look like, but also that there is a way for this

‘concrete utopian’ vision to become shared socially, leading to questions of democracy or social

consensus. Whilst we have precedents for such achievements – take for example how our factual

knowledge about bacteria has led to normative values about cleanliness, or how (it could be argued)

humans have advanced their moral position for the better over time in terms of the question of

slavery – nevertheless there is often disagreement about how we decide what to value, that is, what

constitutes the good, and what normative role, if any, this good should play in processes of

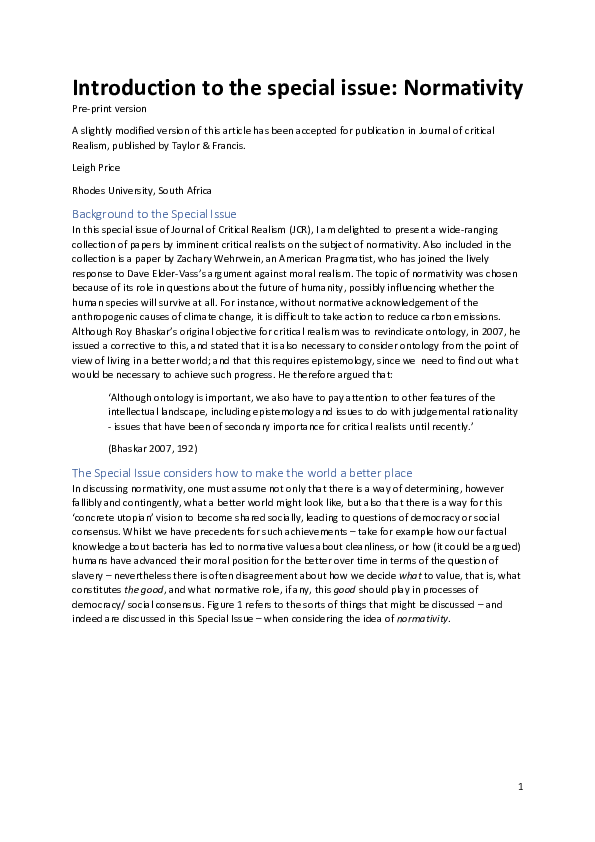

democracy/ social consensus. Figure 1 refers to the sorts of things that might be discussed – and

indeed are discussed in this Special Issue – when considering the idea of normativity.

1

�DIALECTICS AND

EXPLANATORY

CRITIQUE

ONTOLOGY ,

EPISTEMOLOGY

AND

JUDGEMENTAL

RATIONALITY

THEORY AND

PRACTICE

NORMATIVITY

MORALITY,

ETHICS, AXIOLOGY

SOCIETY ,

AGENCY,

REFLEXIVITY

(often includes

religion and

spirituality)

CONCRETE

UTOPIA

POLITICS AND

DEMOCRACY

Figure 1: Considerations often encountered in critical realist discussions about normativity

Comment on the content of the papers

On receiving the contributions to the Special Issue, a clear pattern emerged. First, except for two

papers, most of the authors addressed the normative questions of moral realism, ethical naturalism

and whether facts can lead to values. Whilst some authors were, like Bhaskar, willing to call

themselves moral realists, they nevertheless often differed from Bhaskar in terms of the nature of

their realism (Doug Porpora, Howard Richards, Frederic Vandenburghe). Others, such as Dave ElderVass, Andrew Sayer, and Zach Wehrwein avoided the label of moral realist altogether. Second,

several of the authors (Elder-Vass, Porpora and Vandenburghe) suggested that the problems that

they associate with this discussion could be addressed by engaging with Jürgen Habermas’s (2015)

ideal speech situation, perhaps with some adjustments. These author’s therefore felt that it is

possible to use consensus, not merely to collectively agree to values, but as a kind of epistemology –

consensus in the business of discovering transcendent values (Porpora, Vandenburghe) or in the

business of, in a way, making values (Elder-Vass). Third, all the authors were committed to avoiding

relativism. Nevertheless, how they avoided relativism – their ontological commitments or moral

baseline – was remarkably varied. See Table 1 for a categorisation of the different moral baselines of

the contributors. Margaret Archer and Cheryl Livock/Yahna Richmond were absent from this debate

about moral realism as their papers were focused on the achievement of concrete utopia, as a

general concern (Archer) and in the specific case of Australia (Livock). Archer’s insightful paper was

an intelligent supplementation of Bhaskar’s philosophy with her Morphogenic Approach, as well as a

useful overview of the work on normativity carried out by the Centre for Social Ontology (see also

Archer 2016). Livock/Richmond provided a well-researched and astute account of the detrimental

effect of neoliberalism and its more radical counterpart, neoconservatism, on Australian politics.

Whilst their ambitious paper will certainly be useful for Australians, as a guide to emancipatory

action, it nevertheless has applications beyond Australia.

2

�To assist the readers to negotiate the debate on moral realism, I have included a description of

Bhaskar’s moral realism and ethical naturalism in this Editorial. I have also indicated occasions where

the contributing authors differ from, or are significantly similar to, Bhaskar’s position. In keeping

with a trend reflected by several of the authors (see Elder-Vass, Porpora and Wehrwein), I have used

the question of slavery to illustrate Bhaskar’s position. I have also commented on Bhaskar’s

relationship to American pragmatism, in-so-far as it is relevant to normativity, motivated by the

contribution by Wehrwein.

Bhaskar’s moral realism and ethical naturalism

Bhaskar defines his moral realism and ethical naturalism as follows:

Moral realism specifies a first-person action-guiding relation to, in the social world, typically

a set of relations which includes, but is not reducible to, actually existing moralities which

may be described, redescribed, critically explained (in descriptive, redescriptive and

explanatory critical morality), accepted or changed (reproduced or transformed).

Bhaskar (2008, 174)

Moral realism holds that morality is an objective (intransitive) property of the world. Ethical

naturalism grounds a distinction, within moral realism, between the domains of actually

existing human morality (dm a ), which is susceptible to explanatory critique, and the moral

real (moral alethia or object/ive) of the human species (dm r ), which explanatory critical

philosophy and science may discover.

Bhaskar (2016, 139)

Bhaskar’s moral realism underpins his discussion of ethical naturalism, where it is visible in terms of

the presence of ‘object/ive’ O in his formal inference scheme designed to identify values (discussed

later under the heading of ‘Bhaskar’s formula for ethical naturalism’). The object/ive is also

mentioned several times throughout this editorial. It is what makes Bhaskar’s ethics naturalist and

he describes it as follows: ‘The human moral alethia or object/ive is, I have argued, universal free

flourishing in nature’ (Bhaskar 2016, 139). Bhaskar’s ethical naturalism includes seven levels of

rationality, all of which are involved in human emancipation. I outline them below because one

needs to understand them all to fully appreciate the extensive implications of Bhaskar’s moral

realism.

3

�Author

Bhaskar

Elder-Vass

Porpora

Richards

Sayer

Vandenburghe

Wehrwein

Moral baseline that aims to avoid ‘anything-goes’ relativism

Moral truth is obtained by: initially checking that one’s beliefs about one’s object/ive are not false, with the aim of

removing intra-discursive error; followed by negatively valuing the extra-discursive entity or entities (ills, such as ill health

or social structures) which constrain achieving discursive truth and, ceteris paribus, positively valuing actions to remove the

problematic extra-discursive entity or entities (Bhaskar 2009, 182-194).

Moral ‘truth’ is obtained by consensus in a similar manner to that suggested by Habermas. ‘…just those ethical principles

are valid to which all possibly affected persons could agree’ in an open, truthful context ‘undistorted by differences in

power’ (this issue).

Moral truth is obtained in two ways. First, via a transcendent feeling; which Porpora describes as a ‘calling’ or ‘moral

summons’ (this issue) which ‘implies a connection with religion or at least some grounding secular worldview that treads

on the religious domain’ (this issue). Second, via democracy since (moral) truth is also ‘ a democratic value’ by which

Porpora means that it is achieved in a Habermasian-style deliberative democracy where we do not simply vote for our prereflective prejudices. Instead, we first participate in a public sphere of arguments and counter-arguments about the

common good (this issue).

Moral truth is based on knowledge of extra-discursive entities (biological, ecological and social) that affect the

achievement of human potential. It should therefore be functional (should achieve human potential) whilst also being

diverse (should respect existing cultures, with appropriate exceptions). Communities should learn from experience (history)

to develop their morality to achieve human needs in harmony with nature. ‘Moral rules cannot properly be evaluated

without taking both physical reality and social reality into account’ (this issue).

Moral truth is based on knowledge of extra-discursive entities (natural) that affect the achievement of human potential.

‘Biological normativity involves valuations and oughts that come from the body, and which as feelings may contingently

become the object of conscious valuations. The latter are made via the concepts and value frames available to us, so there

are different ways of interpreting any given feeling, some better than others. ‘We may decide to ignore or override such

valuations, for whatever reason, but we simply wouldn’t survive if we always did so’ (this issue).

Moral truth is obtained by a version of Habermasian consensus; ‘dialogue and discussion, …(and) struggle against the

countervailing mechanisms’ to identify values that really exist in some ‘ideal sphere’ (this issue).

‘It is not because the scientists arrive at a consensus that we can presume that they have arrived at the truth. Rather, it is

the reverse: it is because all the evidence points to the truth that the scientists can arrive at a consensus’ (this issue).

Moral truth is based on knowledge of extra-discursive entities (social entities such as institutions) that affect the

achievement of human potential. Morality is achieved via the ‘experience of institutional arrangements in the service of

facilitating the achievement of the potentialities of human nature’ (this issue).

‘We evaluate our moral norms to the extent to which they are effective in solving our problems, but this is not mere

technical rationality in a Weberian sense as the “solving” occurs in post-Cartesian experience of a community’ (this issue).

Table 1: How Bhaskar and the authors in this Special Issue attempt to avoid moral relativism

4

�The seven levels of rationality involved in emancipation

Bhaskar begins his discussion of the seven levels of rationality involved in human emancipation by

describing instrumental reason (Levels I and II), which make no attempt ‘to question the logical

heterogeneity (and impenetrability) of facts and values’ (Bhaskar 2009, 181). At Levels III and IV

(critical reason), contra David Hume, Bhaskar argues that it is possible to transition from facts to

values. Nevertheless, despite this being a major, and early, aspect of Bhaskar’s work; it remains one

his of his most controversial and at least four of the contributors to this issue of JCR disagree with

him (Elder-Vass, Sayer, Vandenberghe, Wehrwein). For instance, Sayer (this issue) states, ‘(The idea)

that we can logically deduce an ought from a purely factual, non-evaluative statement… is an

absurdly reductive way of thinking about normativity and naturalism’. At Levels V-VI (explanatory

reason), Bhaskar considers how a false belief is usually the result of a source that needs the false

belief to function (or in some ways is the false belief itself). He therefore explores psychological

rationalisation and ideological mystification (Bhaskar 2009, 194). He asks ‘the question of the causes

of these causes’ and looks to ‘the depth human sciences (at their various – e.g. historical,

phenomenological, psychodynamical – levels)’ to identify these causes and test our knowledge of

them. At Level VII (historical reason), Bhaskar considers the vital role played by history in providing

the empirical data upon which we must necessarily ground, and test, our theories about society

(Bhaskar 2009, 216). In the following sections, I will describe each of the seven levels of rationality in

greater detail, but I will give extra attention to Levels III-VI because of their relevance to the

controversial fact-to-value transition.

Levels I-II: Instrumental reason

The first of Bhaskar’s levels of rationality is instrumental rationality (Level I) and it is the only one

allowable by positivism.1 It is based on empirical regularities or constant conjunctions – protolaws –

and is formulated in terms of ends and means. It therefore generates technical imperatives ‘akin to

‘put anti-freeze in the radiator (if you want to avoid it bursting in winter) CP’ (Bhaskar 2009, 181).

Whilst such instrumental decisions can be unobjectionable, such as in terms of vehicle maintenance,

nevertheless they can become questionable, even dangerous, in terms of humans and society. This is

inter alia because the unacknowledged social values inherent in instrumental action – which is

falsely assumed to be objective and thus value-free – allow questionable values to be implemented

without the possibility of challenge. As Hofkirchner (2016, 290) puts it, ‘The moral end becomes

camouflaged and reduced to pretended real necessities’. Think here of Hitler’s instrumental decision

to rid Germany of the Jewish population.2 It is because of the dangers of such instrumentalism that

Hume’s injunction against the movement from facts-to-values has held so much sway, since people

are rightly troubled by it; but their reaction to throw out the fact-to-value transition has created its

own problems related to questions of moral relativism, since if one cannot use science to ground

one’s morals, what can one use? (This issue is discussed further below; see also Sayer, this issue).

The second level (Level II), contextually-situated instrumental rationality, makes use of the same

protolaws as used in Level I and applies them towards improving the world, but whereas Level I is a

Elsewhere I have argued that instrumentality (Level I) contradicts Hume’s Law and this contradiction is based

on another contradiction in the work of Hume, namely that he has two, contradictory, theories of causation: one

which allows for connections between things, if only between empirical things (atoms); and one that disallows

all connections between things (Price 2014). However, the contradiction found in instrumentality is a necessary

one, since without some movement from facts to values, life for humans would be impossible. That is, Hume’s

Law is a compromise formation; since, given that it offers a false version of reality, it must be flouted in practice

if it is to be maintained in theory.

2

The necessary alternative to ends-means instrumentality is prefiguration – in which the end is embodied in the

means (Bhaskar 2016, 139).

1

5

�general rationality, Level II is what actually happens in a context of, for instance, relations of

domination. In this context, Bhaskar assumes that such instrumental rationality is of greater benefit

to the oppressed than to the oppressor. He says, ‘The human sciences are not neutral in their

consequences in a non-neutral (unjust, asymmetrical) world. And it is just this which explains their

liability to periodic or sustained attack by established and oppressive powers’ (Bhaskar 2009, 182).

An example is the statistical data indicating that, for the first time since records began, life

expectancy in the UK has declined (Patrick Collinson 2019). This statistic indicates that there is a

significant problem with the way that society is theorised, that is, it puts into question the

justifications used by government in support of their policy decisions. It therefore challenges the

dominant ideologies; and, not unsurprisingly, the dominant class is often motivated to suppress

information, whilst the oppressed are motivated to find it.

Levels III-IV: Critical reason and the fact-to-value transition

However, to move from the statistic of declining life expectancy to the value judgement that

therefore capitalism must be removed/transformed, based on the theory that capitalism is the cause

of the ill, is not allowed by Humean-based positivism; indeed, neither is it allowed by Bhaskar who,

whilst he agrees that these arguments can and do inform emancipatory strategies, nevertheless

states that his argument ‘does not permit (such) a simple inference from facts to values’ (Bhaskar

1998, 68). The problem is, as already mentioned, that such a simple inference veils a vast

background of value-based assumptions. For instance, depending on their political affiliations,

authors might have different theories to explain the statistic. They might therefore argue that the

decline in life expectancy is not due to the effect of capitalism, but the effect of an aging population

or a life-threatening influenza virus. Critical realist would use judgemental rationality to decide

amongst these competing theories, but even in the event that the true cause is relatively clear, the

false beliefs often remain entrenched. One example – which occurred in the 1600s, where the truth

was obvious and known by some, but the falsity nevertheless remained generally believed – was

rejection of Copernicus’s heliocentric theory championed by Galileo. In a contemporary example, we

have the popular rejection of the theory of climate change. The acceptance of truth, in both these

instances, was constrained by the dominant social values of the time. In Galileo’s case, the social

values in question were based on religion; in the climate change case, they are based on neo-liberal

economics. It is for this reason that Marx objected to criticism – because it employs value, especially

but not necessarily moral value – in terms of the absence of any kind of causal grounding (Bhaskar

2009, 179). This point is also emphasised by Doug Porpora who says that the secular contentment

with ungrounded ethics ‘bothers’ him; however, his solution (this issue) – which is to ground morals

in the (religious) experience of a ‘calling’, defined as ‘a feeling that arises from a source outside us

that impresses us with what we experience as a moral summons’ – is significantly different from

Bhaskar’s (2009, 180-211) secular3 solution, which I outline in the paragraphs that follow, which

avoids the impasse by differentiating between intra-discursive and extra-discursive value.

At Level III, Bhaskar argues that all the sciences are intrinsically critical and therefore evaluative

because they involve criticism of other actually or possibly believed (and therefore causally

efficacious) theories. Therefore, they value the discovery of truth; that is, to say that ‘P is false’ (fact)

does not mean ‘don’t believe (act on) P’ (value) but it certainly ceteris paribus (CP) entails it. Bhaskar

further explains that even if ‘P is false’ is not value neutral (as is indicated in the prescriptive

Bhaskar states that ‘secularity is an important principle to up-hold’ (Bhaskar and Hartwig 2010, 168).

However, although Bhaskar’s ethical naturalism is a secular solution to morality, he also considers it to be

compatible with a certain version of immanent spirituality, which he explores in his books on metaReality

(Bhaskar 2012a, 2012b). Porpora’s assumption that morality requires some kind of access to religion or

religious-like experience is different from Bhaskar’s acknowledgment that critical realist secular morality is

compatible with an immanent spirituality. Specifically, Bhaskar’s version can stand alone as a secular version;

whereas Porpora’s version requires religion or religious-like experiences.

3

6

�component involved in truth claims), then the value-judgement ‘P is false’ can be derived from the

premises concerning the mismatch between the Object (O) and the believe about the Object (P). To

deny this connection between beliefs and action or theory and practice ‘makes practical discourse

practically otiose’ (Bhaskar 2009, 183). However, if P is false is value neutral, it certainly seems

inescapable that it is not followed by the inference that ‘P ought not to be believed’ and ‘Don’t act

upon P’ (Bhaskar 2009, 184).

However, Bhaskar argues that to suggest that the value of truth exists in science – which translates

into specific values of integrity, veracity, responsibility, coherency, honesty etc – does not vindicate

Hume’s Law, as is suggested by both Vandenburghe (this issue) and Elder-Vass (this issue). For

instance, Vandenburghe (this issue) states, ‘there’s a suspicion that the conclusion of the argument

only follows because Bhaskar has already smuggled the values into the facts. Indeed, the premise

that a statement is false can hardly said to be neutral.’ According to Bhaskar (2009, 184), this

objection fails to acknowledge that to hold that a statement is false (bad) is to hold a different kind

of value to the one’s objected to in the ‘simple inference of facts to values’. The scientific values

involved in truth seeking are simply unavoidable and are part of (intrinsic to) all factual discourse,

indeed, I would say, that they are intrinsic to even the most basic cognitive activity. Therefore, when

a cat misjudges the distance to the windowsill and as a result falls to the ground, my guess is that

one way or another they are aware that they have made a mistake and will adjust their judgements

accordingly in the future. For them, ‘P is false (window not so close)’ leads to ‘don’t believe (act on)

P’, that is, don’t believe the window is so close.4 Bhaskar’s genius is to apply the specific instance – in

which a fact-to-value transition is unobjectionable because it is intrinsic to all cognitive activity – to

all instances of moral judgement, even those that are not intrinsic to factual discourse. He therefore

provides a legitimate version of the fact-to-value transition in the broader sense, for questions such

as whether or not capitalism is a good thing.

Bhaskar calls this process explanatory critical or practical rationality (Level IV), and it takes the

following form: If we assume that obtaining truth is a good thing, then this leads to positively valuing

those things that help us to achieve truth and negatively valuing those things that constrain our

What makes Bhaskar’s approach to facts-values possible is simply the nature of all being as deeply connected

rather than separate; we are therefore all part of ‘totality’. He says (Bhaskar 2008, 273) ‘Ontological

extensionalism (externalism or separatism) is manifest too in the Humean doctrine and post-Weberian

orthodoxy, that there can be no transition from an is to an ought – i.e. values are detotalized.’ I suspect that this

is difficult for people to understand if they are committed to a Cartesian or Kantian split between their mind and

body/world or as Bhaskar put it, ‘the denial (implicit or explicit) of an ontological connection between beliefs

and actions, theory and practice’ (Bhaskar 2009, 194). What I find puzzling, though, is that those people who

deny this connection, and who therefore find this approach difficult to grasp, then find it easier to believe

instead that values exist in an other-worldly transcendent ideal sphere, from which it is not far to the next step,

which is that these values must be transferred to humans by a transcendent (usually male) god? Yet, it seems

much easier to believe that we are all part of totality and thus connected, given the overwhelming evidence for it

(even my cat gets it). I should add that I am not here arguing against all the reasons to believe in God, I am

merely suggesting that the Kantian ‘proof of God thesis’ is flawed (Byrne 2017). Feminist theologians should

find Bhaskar’s approach of particular interest because it is their contention that: a) it is the mind/body split,

whether in Cartesian or Kantian forms, that results in the belief in a transcendent male God of the monotheistic

religions; and b) these monotheistic religions are the basis of the patriarchy and ultimately most, if not all,

heteronomy including capitalism (Plumwood 1991, 2002; Christ and Plaskow 1992). This perhaps addresses my

puzzlement about why it is so difficult for some to accept that the nature of reality is deep connection rather than

dualism and split; their denial is necessary for the maintenance of the patriarchy by the world’s monotheistic

religions. However, if this is the case, then it is also the case that critical realists are faced with the identical

problem that confronted Galileo 400 years ago; which is that the monotheistic religions are constraining critical

realist philosophy (Gironi, 2012) because the existence of these religions as up-holders of patriarchy is

dependent on the false belief that critical realism critiques, in this case, the false belief that there is a split

between mind and body/world .

4

7

�achievement of truth. In the natural sciences, such ‘things’ might include appropriate instruments

and specialist training; and if these things are missing, attempting to obtain them is justified (CP). In

the social sciences, such ‘things’ might include an independent press and freedom of expression; and

if these things are missing, attempting to obtain them is justified (CP)(provided that there would be

no resulting no significant ill effects and that a better course action does not exist that would be

equally successful). These judgements, to remove things that constrain truth-seeking, are not

intrinsic to all factual discourse, whilst they are nevertheless justified by judgements that are

intrinsic to all factual discourse. Therefore, as Bhaskar suggests, ‘we do have a transition here that

goes against the grain of Hume’s Law, however it is supposed to be interpreted or applied’ (Bhaskar

2009, 184). So, to reiterate, Bhaskar agrees that it is problematic to use extra-discursive entities

(unwanted constraints such as ill health, social dysfunction, and systematic self-deception) to inform

ethics and emancipatory strategies; and that ‘it is precisely on this rock that most previous attempts

at its refutation … have foundered’ (Bhaskar 2009, 192). Porpora (this issue) shares this concern; he

says, ‘I do think we need some basis other than collective prudence to ground a non-arbitrary ethical

position’.

Bhaskar’s ethical naturalism offers an alternative to instrumentalism

In this issue, we have several examples of attempts to inform ethics by reference to extra-discursive

entities such as human and environmental ill health or dysfunctional social institutions (see Table 1).

The question is whether these attempts manage to avoid instrumentalism. For instance, Sayer (this

issue) describes his naturalism as being based on critiques of forms of ill-being and suffering and

restricted flourishing. He argues that this requires an everyday normativity, which is an emergent

outgrowth of biological normativity; the latter involving valuations and oughts that come from the

body and which as feelings may contingently become the object of conscious valuations. For Sayer,

such valuations are made via the concepts and value frames available to us and, therefore, there are

different ways of interpreting any given feeling, some better than others. He states:

We may decide to ignore or override such valuations, for whatever reason, but we simply

wouldn’t survive if we always did so.

(Sayer this issue)

There is another naturalist who makes similar statements:

Eternal Nature inexorably revenges the transgressions of her laws.

Man, by trying to resist this iron logic of Nature, becomes entangled in a fight against the

principles to which alone he, too, owes his existence as a human being. Thus his attack is

bound to lead to his own doom.

(Hitler 1941, 393-4, 84; he is here arguing that extermination of the Jews is a natural

necessity, akin to the way that nature carries out natural selection or population control)

Sayer (this issue) has anticipated the argument that his position is similar to Hitler’s instrumentalism,

which he counters by explaining that ‘To be sure, there are appalling cases of the mis-use of biology

in understanding the social world, such as in eugenics and Nazism, but mis-uses should not drive out

good uses.’ However, as I see it, a problem with this approach to morality is that no matter how

noble one’s intentions, one’s ideas of ‘good’ are saturated in cultural and personal prejudices. One

might try to add goodness to one’s ideas of morality by ensuring that they are from God, perhaps as

a kind of moral intuition or ‘calling’ or by reference to a religious text; or perhaps one could say that

something is only good if a majority of people think that it is good (examples of both these positions

8

�can be identified in Table 1). However, we know that this is not in itself enough because Hitler used

God to justify his ethics, too; and his consensual populism, guided by what he called the ‘folkish view

of life’ is well-acknowledged (1941, 582). In terms of religion, he wrote, ‘By warding off the Jews I am

fighting for the Lord's work’ (1941, 84). He also wrote:

If one were to take from present mankind its principles based on religion and faith, which in

their practical effectiveness are ethical and moral, by eliminating this religious education and

without replacing it by an equivalent, one would be confronted with a result amounting to a

serious undermining of the foundations of their existence.

(Hitler 1941, 574)

My guess is that Sayer is somewhat ambiguous about his conclusion that we must commit to

biologically-based instrumentalism – he says that he changed his mind about it – because, whilst he

knows its dangers, he feels that there is no other option. I think we can safely assume that he would

not endorse the religious or consensus alternatives. Similarly, I wonder whether those authors, such

as Elder-Vass, Porpora and Vandenberghe, who do resolve the issue of relativism via religion and/or

consensus, possibly also decided on these options – despite their dangers – because they think that

there is no alternative. However, Bhaskar’s ethical naturalism is a viable alternative.

Bhaskar critiques both the left and right for their instrumentalism

I honestly do not intend to single out Sayer for his position. In fact, unless we fall into the religious or

consensualist categories, I suspect that we are all, probably, guilty of it. I know that I am. Despite

already being a critical realist, in my (2007) PhD thesis on environmental education I argued that we

should be guided by the environment itself, through the research obtained in relatively independent

research institutions. This is much like Sayer saying that we should be guided by biology. It was only

much later, when I began reflexively exploring the meaning of Bhaskar’s interdisciplinarity, that I

began to change my position, but the change was slow. It can be seen in my (2014, 2015) papers on

the emancipation of women, where I engage with the explanation of men’s often injurious actions

towards women and suggest that rather than identifying men as the enemy, we should engage them

as friends and find out the deep explanations for why they act in harmful ways, as well as enabling

women’s agency by exploring what we can do to change the situation. This of course is controversial,

because to say that women have agency can be spun in such a way as to suggest that they are

somehow culpable, that is, to blame the victim. However, Bhaskar’s version of emancipation

requires self-reflexivity because, as he explains (2009, 210), ‘critique … is part of the very process it

describes, and so subject to the same possibilities of unreflected determination and historical

supercession it situates. Hence continuing self-reflexive auto-critique is the sine qua non of any

critical explanatory theory’. What is liberating for me about Bhaskar’s approach is that it challenges

the basis of polemics and politics. As Hartwig explains in Bhaskar and Hartwig (2010, 206), ‘although

it comes out of the tradition of the left, there is a sense in which critical realism wants to go beyond

left and right. That is the overall trajectory: transcending the big oppositions.’ Therefore, Bhaskar

(2008, 369) criticises both the left and the right for ‘using instrumental rather than explanatory

critical reason’. 5

5

I extend the criticism of the left and right by arguing that they are both also, at times, consensualist and

religionist (admittedly, the left probably less so in terms of religionism, more so in terms of consensualism).

Please note that I am not arguing against all the roles of consensus and religion, merely their roles in

determining values and morality. Furthermore, I distinguish between religion and spirituality. As an atheist, I

have no problem with the idea that Bhaskar’s secular version of moral realism could be described as a kind of

secular spirituality, if one defines spirituality as the search for meaning in life, that is, the search for ‘the good’.

9

�Bhaskar has turned the usual approach to emancipatory praxis on its head

Bhaskar’s naturalistic approach to ethics therefore turns the usual approach to emancipatory praxis

on is head. This is because, instead of first focusing on human, social and environmental ills

(followed by consideration of the states of affairs and false beliefs that facilitate these ills); it first

focuses on the false beliefs and states of affairs related to the object/ive of human flourishing

(truth). It therefore sidesteps the limitation that starting from ills means that we start with our

personal and socialized prejudices; and thus is saves us from Hitler’s version of ethical naturalism in

which the possibility that we may be mistaken about something being an ‘ill’ cannot be

countenanced and is therefore never addressed.

For instance, consider parents who discover that their son is gay. Starting from this ill (as they

consider it), they might have a strong, honestly-experienced feeling that their gay son would be

better off not being gay. This might result in their being ‘called’ to identify and remove their son’s

‘illusory beliefs’ about himself by sending him to conversion therapy. This is critique without

explanation; and it is steeped in unreflected prejudices. Using Bhaskar’s version of explanatory

critique, the parents of the gay child – perhaps motivated by their son’s anguish because of their

disapproval and rejection of his identity6 – would instead consider both their own, their son’s,

respected others’ and scientific theory surrounding what is best for people who are gay (apply their

intrinsic-to-discourse value of truly knowing what is best for their child, that is, the morally real,

intransitive object/ive O). They would use retroduction and judgemental rationality to consider the

best explanation of O, thus fallibly identifying whether or not they hold a illusory belief P about it,

most likely arriving at the idea – since it is currently preferred by a majority of health professionals

and based on sound science – that being gay is nothing to do with choice and that conversion

therapy is not only unsuccessful but increases the chances of self-harming and suicide (Clucas 2017;

Powell and Stein 2014; Haas et al ).7 That is, they would discover that their theory about O is

inadequate/false.8 They would then consider what stops them from believing this truth S (e.g. their

church’s beliefs, their narcissistic personality structures), decide to negatively value S (e.g. decide to

change their church or go to therapy themselves), and, thus ceteris paribus (CP), act to remove S

(although the choice of action will depend, for example, on their unique circumstances – if they live

in the repressively homophobic Chechen Republic they would probably not support their son by

flying a rainbow flag outside their house). This then gives us a formula for ethical naturalism that is

sublative of the key motivation to avoid the fact-to-values transition (to avoid the tyranny of

unreflected prejudices), whilst nevertheless still allows science to inform morality. Note that this

example could be seen to imply that it is quite simple to change false beliefs, as simple as changing

one’s church, but for beliefs kept in place by behemoth institutions such as capitalism, or

This is not to say that the agent’s interpretation about what is good for them is incorrigible, whilst nevertheless

one can also assume relative privilege for the agent’s account (Bhaskar 2009,164). Neither is it to say that what

people want is always what is best for them, indeed, as Bhaskar explains (2009, 208) ‘it is just this which gives

moral dialogue its characteristic normative bite’. In this case, the discrepancy between the son’s views and the

parents’ views simply provides the warrant for further investigation.

7

Bhaskar states that a depth enquiry is prompted or informed, at the initial stage, by a view about human nature,

which may well be refined, revised or refuted (or perhaps confirmed and consolidated) in the depth enquiry

itself (2009, 206).

8

Alternatively, they may discover that they were deceiving themselves and others about their object/ive O.

Whilst ostensibly O was the wellbeing of their son, the real O was their own wellbeing, threatened by a) the

embarrassment of having a gay son, and b) the consequences of deciding against the religious disapproval of

homosexuality, since this would mean changing their relationship with their religion. However, whether they are

deceived because their transitive belief about O is false or their real O is not their stated O, either way, the truth

will have been identified.

6

10

�entrenched personality disorders, such as narcissism, it can be extremely difficult. Depth

explanations of these entities – the causes of the causes – may be a required further step.

I have chosen this example because many members of the LGBTQ community are understandably

wary of any moral system that calls on nature for its justification, given that they have so often been

accused of being ‘against nature’. However, Bhaskar’s version of ethical naturalism has nothing in

common with, in fact it is an antidote, to the positivistic, instrumental idea – which hides unreflected

prejudice – that nature ought to tell us what to do. That is, critical realism, properly applied, is

relentless and indiscriminate in its uncovering of prejudice/false beliefs, which can only be a good

thing for marginalized people. Honest people have nothing to fear from truth. Of course, this

misunderstanding of Bhaskar’s approach, that it allows ‘nature’ to be used to justify prejudice, works

the other way; for instance, transphobic people may be disappointed to discover that Bhaskar’s

ethical naturalism will not necessarily justify their idea that transgender people are suffering from an

‘ill’. A relevant debate can be found between Pilgrim (2018a; 2018b) and Summersell (2018a;

2018b).

I will now outline ethical naturalism as formalised by Bhaskar.

Bhaskar’s formula for ethical naturalism

Bhaskar’s (2009, 182-194) formula for his ethical naturalism is often quoted in its unqualified form

and/or not enough emphasis is placed on its ceteris paribus (CP) clause (see for instance Elder-Vass

2010, 35). This is understandable because Bhaskar himself does not always include the last two

steps, perhaps because he assumes that they are implied when he includes the CP clause (these

steps are provided in Bhaskar 2009, 188). Nevertheless, the effect of using only the first four steps of

the formula, rather than the full six steps, can lead to the impression that Bhaskar’s formula is

‘formulaic’ because it provides an absolutist or abstract universalist moral realism, which could not

be further from the truth. The full form is:

(i) Our theories show that some belief P about a (morally real, intransitive) object/ive9 O is

false;

(ii) Our theories show why that false (illusory, inadequate, misleading) belief P is held, for

example, perhaps it is due to the effect of a system of social relations, object S (whilst also

being aware that there may be more than one problematic belief) leading to;

(iii) a negative evaluation of the object S accounting for the falsity of the belief P (i.e.

mismatch in reality between the belief P and what it is about O) and

(iv) a positive evaluation of action rationally directed at removing (disconnecting or

transforming) that object S, i.e. the source(s) of false consciousness (CP); but the CP clause

means that this axiological judgement must be adjusted for its feasibility and it must be

compared to alternatives that may be better, furthermore, since diagnosis is not therapy, we

will need to develop theories about how to change things, even though we already have

theories explaining that they need to change, leading to;

(v) the Concrete Axiological Judgement (CAJ), which is specific to the geohistorical context

(thus avoids abstract universalism); and given that the CAJ is sincerely held and can attach

itself to any necessary affect and/or desire, so as to find expression in a want, and if the

Bhaskar only began referring to this as the ‘Object/ive O’ in his later (2016) work. In earlier work he simply

referred to it as the ‘Object O’.

9

11

�agent can muster the appropriate powers and circumstances as are described and

presupposed by the CAJ, then;

(vi) the action must occur.

The CP clause is hugely important; because of it, that is, because of the open world, Bhaskar (1998,

70) suggests that it is ‘a mistake of the greatest magnitude to suppose that (science) will tell us what

to do’ and that, therefore, even ‘the most powerful explanatory theory in an open world is a

nondeterministic one’. In other words, a transcendentally realist ontology requires as much

readjusting in ethics as in epistemology, so that just as we can have a power or tendency present at

the level of the real but not manifest at the level of the empirical because of the open world, so we

can have a concrete (not abstract) universal value judgement present at the level of the real but

inappropriate in certain circumstances for guiding action at the level of the empirical, again because

of the open world.

Furthermore, ‘science cannot finally “settle” questions of practical morality and action, just because

there are always – and necessarily – social practices besides science, and values other than cognitive

ones; because, to adapt a famous metaphor of Neurath’s, while we mend the boat, we still need to

catch fish in the sea’ (Bhaskar 1998, 70). It is because of science’s inability to settle questions of

morality, whilst nevertheless it is able to inform those questions, that normativity requires public

debate and democracy. In this issue, Elder-Vass and Vandenberghe suggest, in different ways, that a

readjustment of Habermas’s (2015) discourse principle might provide a way address this issue of

how to develop community consensus around norms, given that science cannot tell us what to do. A

major difference between these two authors and Bhaskar is that Elder-Vass and Vandenburghe see

community consensus as more than a way to develop a unified vision of normativity, they also see it

as an epistemology, a way of identifying truth. Bhaskar does not think that consensualism is a valid

epistemology. He states, ‘Consensus theories are subject to the dilemma that if given a strict

interpretation, twenty million Frenchmen can be wrong – or if given an ideal-typical formulation,

that they do not explicate our existing concept of truth’ (Elder-Vass provides us with a strict

interpretation of consensus theory, whereas Vandenburghe provides us with an ideal-typical

interpretation).

I now turn to levels V – VII of Bhaskar’s typology of kinds of emancipatory reason.

Levels V – VI: Emancipatory reason

Given the epistemic priority of the explanatory-critique of consciousness, it is not surprising that

Bhaskar’s Levels V – VI focus on ‘the depth sciences’ that deal with consciousness (historical

materialism, psychoanalysis and social phenomenology or anthropology). He therefore suggests that

the kinds of things that might stop human beings from being able to achieve truthfulness include

psychological rationalisation (motivated for instance by our narcissistic egos) and ideological

mystification (motivated by for instance by the institutions behind social inequality). Bhaskar (2009,

206) explains, ‘On this road, the question which interests us is no longer merely the simple one of

the causes of beliefs and action, it is the question of the causes of these causes…’. However, none of

these levels can be dealt with separately and therefore constraints upon cognitive emancipation are

the consequence of the imposition of ideologies into practical life by ‘the material imperatives of

social life (in historical materialism), by the preformation of ideational contents (in psychoanalysis)

and by the projects of others (in social phenomenology). Hence emancipation can no more be

conceived as an internal relationship within thought (the idealist error) than as an external

relationship of “educators”, “therapists” or “intellectuals” to the “ignorant”, “sick” and “oppressed”

(the typical empiricist mistake)’ (Bhaskar 2009, 205).

12

�Level VII: Historical reason

Bhaskar’s Level VII is relevant to praxis as it describes the way in which we test out our theories in

our practical application of them, that is, we look back to see how things have worked out for us,

and use this historical information to adjust our theories and change our practice. It therefore

assumes that our theories about society require concrete historical (including of course

contemporary) research (Bhaskar 2009, 216). For instance, Bhaskar states that ‘Although social

theories can be refuted, they cannot be confirmed or creatively elaborated, independently of the

historian’s skill – for human history is the only testing ground for social science, the open lab. into

which almost anything can wander and from which the most vital piece of evidence may seem free

to leave’ (Bhaskar 2009, 216). He also makes the point that one can never use history, or what has

gone before, to predict the future; however, this does not mean that we cannot learn from history.

He states (2009, 221), ‘In open-systems, criteria for theory assessment cannot be predictive and so

must be exclusively explanatory; deducibility can at best serve as a criterion for our knowledge of

tendential necessities…’.

In the next section, I will apply all seven levels of Bhaskar’s ethical naturalism to the question of

slavery.

Bhaskar’s ethical naturalism applied to the question of slavery

According to Bhaskar’s ethical naturalism there is little point, in the first instance, in asking whether

slavery is wrong. Rather, we should consider the potentially false beliefs associated with the

discourse surrounding slavery. It would be better, therefore, to ask: is it true that slavery is good for

slaves?10 This belief was a standard part of the discourse about slaves at the time; although it is not

unsurprising that it was more likely to be believed by the slave-owners than the slaves (Escott 1979;

Coates 2010). However, it is fairly simple to demonstrate that slavery is not good for slaves; one

needs only to refer to, for example, statistics of life expectancy, to one’s own empathy (‘I would not

like slavery’) and to personal testimony. It is not that hard to imagine the existence of this belief,

since there is a similar belief currently in existence, which is that wage-labourers have just as much

potential to be happy as those who belong to wealthy classes; and, indeed, that if they are not

happy this is because of poor mental health. Therefore, the solution to discontent amongst the poor

is, it is argued, not to improve their lot, but to improve their mental health (an idea critiqued by

Price 2017). The best-known advocate of this belief is Baron Richard Layard, also known as the UK

government’s ‘happiness guru’ (Layard 2011; Clark et al 2018). As Simone de Beauvoir explains, in

terms of subordinated people, specifically in her case women, ‘It is always easy to describe as happy

the situation in which one wishes to place them’ (in Price 2017, 460).

To return to the slavery of the 17th and 18th centuries, the false believe that slaves were better off as

slaves was not just necessary to persuade slaves that slavery was in their best interests, a goal that

was at times achieved (as described in the historical documentation of slavery by Coates 2010), but

to keep the slave-owners committed to the slavery too. Psychopaths and sociopaths aside, most

people – including slave-owners – do not fare well if they are systematically involved in hurting other

people, for instance, they potentially suffer from perpetration induced traumatic stress (MacNair

2002; Pitts et al 2013). The lie that slavery was good for slaves enabled the slave-owners to suppress

their subconscious knowledge that what they were doing was harmful. However, when slavery was

originally critiqued as being wrong, the existence of the false beliefs that facilitated slavery were not

explained. Therefore, the actions that were derived from the value judgement that slavery was bad

This assumes that there is a morally real intransitive object/ive ‘that which is good for slaves’ (Bhaskar 2016,

139).

10

13

�were merely instrumental, such as changing the legal status of slaves and educating people about

the wrongness of slavery. No attempt was made to challenge the capitalism that needed the false

beliefs in order to justify slavery. As a result, one could argue that the instrumental solutions have

only marginally improved the situation in which black people now find themselves; and therefore,

that the criticism without explanation was ‘impotent’ (Bhaskar 2009, 194). One way of looking at

things is to say that the black population has merely been allowed to join a different class of slaves,

the working class, who are only nominally ‘not slaves’ (Bhaskar frequently refers to the ‘capitalistworker’ relationship as one of ‘masters-slaves’). One might go so far as to say that many white

middle-class people – who pat themselves on the back because slavery is no longer legal and who

believe that low income people in the capitalist system are just as happy as rich people – remain as

self-deceived as their slave-owning ancestors. In those days, to suffer from one’s slavery and thus to

want to escape it was named ‘drapetomania’ (White 2002, 41); today one’s suffering is instead

identified by reference to the broader mental health categories of depression, drug addiction or

work avoidance syndrome.

In other words, to say that some belief P is illusory – such as to say that the belief that ‘slavery is

beneficial for slaves’ is illusory – is ceteris paribus (CP) to imply that P is harmful to the achievement

of human goals and the satisfaction of human wants. However, to re-iterate, it is not because of this

harm that one makes the claim that the belief P ‘slavery is beneficial to slaves’ is bad (Bhaskar 2005,

70). Rather, one makes the cognitive claim that P is bad because it is untrue. Based on this kind of

reasoning, one is then able to arrive at a negative evaluation of whatever it is that prevents proper

cognition, namely in this case, the capitalist mode of production (CP); and a positive evaluation of

action rationally orientated towards its transformation (CP). In other words, it is because the

capitalist mode of production functions to facilitate belief in falsities that one can argue that it

should be replaced. This argument is achieved without recourse to any value judgements other than

those related to the way that cognition works.

Moral realism, critical realism and American Pragmatism

At this point, the discussion becomes relevant to the welcome contribution to this issue of JCR from

the American Pragmatist, Zachary Wehrwein, who is influenced by John Dewey [1859-1952] and

William James [1842-1910]. Despite their significant differences, Wehrwein may appreciate

Bhaskar’s suggestion that we consider explanation in addition to critique. This is because Bhaskar

thus suggests, as does Wehrwein, that we consider the role of institutional structures that facilitate

the problems in the world. Nevertheless, there is another classic American Pragmatist, Charles

Sanders Peirce [1839-1914] who takes a different view from that of Dewey and James. He explains

that he belongs to ‘that class of scallawags’ who ‘purpose to look the truth in the face, whether

doing so be conducive to the interests of society or not. Moreover, if I should ever attack that

excessively difficult problem, “what is for the true interest of society” I should feel that I stood in

need of a great deal of help from the science of legitimate inference’ (Peirce in Haack 1998, 42). We

therefore have two different approaches to the American Pragmatist idea that we must keep the

end in mind, when we are judging truth. As Peirce explained:

[A]gainst the doctrine that social stability is the sole justification of scientific research…I have

to object, first, that it is historically false…; second, that it is bad ethics; and, third that its

propagation would retard the progress of science.

(Peirce in Haack 1998, 44)

To the contrary, in Dewey’s account, science’s end is a social good. That is, truth is measured as such

because it is in the service of facilitating the achievement of the potentialities of human nature, the

14

�goodness of which Dewey believes in ‘faith without basis and significance’, that is, without

grounding.11 Note how this differs from the position of Bhaskar, Marx and the contributors to this

Special Issue of JCR; all of whom want some kind of grounding for such faith. Dewey also describes

this social good as ‘the experience of the institutional arrangement itself’ (both Dewey quotes in

Wehrwein, this issue). Peirce’s ‘scallawag’ position therefore has some echoes in Bhaskar’s position,

since Bhaskar’s truth also does not make a false belief bad because it is harmful. Nevertheless,

Bhaskar and Peirce differ in terms of how one might obtain truth. For Peirce (in Haack 1998, 22),

truth is conformity to something independent of what any individual or group of people might think

it is (which makes Peirce a realist), but this truth is the Final Representation, the Ultimate Opinion,

and it is what would be agreed were inquiry to continue long enough. This makes him a Pragmatist

which – when interpreted in a certain way, as Wehrwein explains (this issue) – gives us Rorty’s and

Elder-Vass’s position.

The way I see it, one might be originally motivated to make the world a better place, but to achieve

this, one must first set aside one’s prejudices about what might achieve this goal, which also means

setting aside prejudices about the ‘the potentialities of human nature’ (these prejudices are

secreted, for instance, in Dewey’s ‘faith without basis’). Instead, one simply searches for truth, even

if this makes one question one’s faithful beliefs. That one ought to be open to changing one’s mind is

well acknowledged. As Porpora (this issue) explains ‘To the extent that we as citizens enter the

public sphere in good faith, we are to let the encountered arguments influence us and, where

warranted, to change our views’; however, unlike Porpora, Bhaskar does not rely on other people’s

arguments, but rather reality as it is (fallibly) known by science, to play a key role in the process of

changing one’s mind.

Conclusion

Normativity is an umbrella term for several philosophical concerns (Figure 1), all of which were

mentioned by the authors represented this Special Issue of JCR. However, their over-riding concern

was related to the question of the legitimacy of Bhaskar’s moral realism and ethical naturalism. In

addressing this concern, the authors were differentiated by their commitment to, or rejection of,

moral realism; and their methods of determining morality (see Table 1). Several authors felt that

Habermas’s (2015) epistemologically-based, consensualist discourse ethics was best suited as a

guide to the development of normativity. Others were committed to a naturalist ethics grounded in

what is good for humans/society. Whilst this may seem similar to Bhaskar’s position, for whom there

exists an intransitive moral object/ive, nevertheless it is in fact significantly different because

Bhaskar formalises the need to consider whether the initial conceptions of the good are not based

on false beliefs. That is, Bhaskar starts with intra-discursive error and CP negatively values those

extra-discursive entities that constrain truth. Therefore, for instance, capitalism is CP negatively

valued in the first instance because of its ideological constraints on truth. This leads to an ethical

naturalism that includes the historical, phenomenological, psychodynamical depth sciences

necessary to uncover psychological rationalisation and ideological mystification. It avoids the key

objection to the transition of facts to values, which is that such a transition hides a plethora of

hidden biases and prejudices. Bhaskar’s naturalistic ethics also avoids another key objection, which

is that a naturalistic ethics must necessarily be absolutist. It does this by insisting that, whilst

11

I appreciate that many people, especially Rorty, have exploited tensions in the writings of James and Dewey

to over-emphasise their concern for social and political issues (Haack1998, 23-24 and 63). However, at the very

least, it may be useful to explore how critical realism might underlabour for – remove the tensions evoked by –

Dewey’s and James’s concern for the application of science as the basis of wise and effective social

transformation.

15

�morality (what is best for the free flourishing of all) might exist at the level of the real, the way that it

should be interpreted at the level of the actual is always extremely contingent and therefore

variable, as a result of the open system. Bhaskar refers to values applied to actual contexts as

Concrete Axiological Judgements. In this way, Bhaskar provides a way for science to contribute to

human emancipation whilst avoiding the tyranny that results from absolutism and the existence of

unreflected prejudices in agents’ attempts to make the transition from facts to values.

In this editorial, I have used the example of slavery to illustrate Bhaskar’s approach to exploring

issues of morality. I have demonstrated that it is not enough to base our actions on a critique of

slavery, since this is likely to result in instrumental solutions; we must also explain the presence of

the false beliefs that underpin slavery. Finally, I have briefly considered how American Pragmatism

compares to critical realism and suggested that, despite clear differences, the Pragmatist that seems

most similar to Bhaskar is ‘scallawag’ Charles Sanders Peirce because neither of them starts their

epistemological investigations with assumptions – nebulously based on feelings, intuitions or

received wisdom – about what is best for humans/society. Rather, they start by searching for truth

which, Bhaskar explains, includes questioning one’s assumptions about what is best for

humans/society. Simply put, every substantial decision made in the absence of truth is likely to be

less than optimal. I do not think that it is coincidental that the world is currently facing both an

unprecedented crisis in truth and an unprecedented socio-economic-ecological crisis. An ethics that

prioritises truth and associated values of honesty and integrity may well be our only hope for

survival.

References

Archer, Margaret S., ed. 2016. Morphogenesis and the Crisis of Normativity. Volume 4, Centre for

Social Ontology Series in Social Morphogenesis. Dordrecht: Springer.

Byrne, Peter. 2017. "The Positive Case for God." In Kant on God, pp. 87-110. London: Routledge.

Bhaskar, Roy. 2009 [1986]. Scientific Realism and Human Emancipation. London: Routledge.

Bhaskar, Roy. 1998 [1979]. The Possibility of Naturalism: A Philosophical Critique of the

Contemporary human sciences. London: Routledge.

Bhaskar, Roy. 2008. Dialectic: The Pulse of Freedom. London: Routledge.

Bhaskar, Roy. 2012a. Reflections on MetaReality: Transcendence, Emancipation and Everyday Life.

London: Routledge.

Bhaskar, Roy. 2012b. The Philosophy of MetaReality: Creativity, Love and Freedom. London:

Routledge.

Bhaskar, Roy, and Mervyn Hartwig. 2010. The Formation of Critical Realism: A Personal Perspective.

London: Routledge.

Bhaskar, Roy. 2016. Enlightened Common Sense: The Philosophy of Critical Realism. London:

Routledge.

Christ, Carol and Plaskow, Judith. 1992 [1979]. Womanspirit Rising: A Feminist Reader in Religion.

San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco.

16

�Clucas, Rob. 2017. "Sexual Orientation Change Efforts, Conservative Christianity and Resistance to

Sexual Justice." Social Sciences 6 (2): 54.

Coates, Ta-Nehisi. 2010. Slaves Who Liked Slavery. Jun 24, 2010. The Atlantic.

https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2010/06/slaves-who-liked-slavery/58678/

Collinson, Patrick. 2019. “Life expectancy falls by six months in biggest drop in UK forecasts.” March

7, 2019. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2019/mar/07/life-expectancyslumps-by-five-months

Escott, Paul D. 1979. Slavery remembered: A record of twentieth-century slave narratives. Chapel

Hill: University North Carolina Press Books.

Gironi, Fabio. 2012. "The Theological Hijacking of Realism: Critical Realism in ‘Science and Religion’."

Journal of Critical Realism 11 (1): 40-75.

Haas, Ann P., Mickey Eliason, Vickie M. Mays, Robin M. Mathy, Susan D. Cochran, Anthony R.

D'Augelli, Morton M. Silverman et al. 2010. "Suicide and suicide risk in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and

transgender populations: Review and recommendations." Journal of Homosexuality 58 (1): 10-51.

Habermas, Jürgen. 2015 [1981]. The Theory of Communicative Action: Lifeworld and Systems, a

Critique of Functionalist Reason. Vol. 2. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

Hitler, Adolf. 1941[1925]. Mein Kampf. New York: Reynal and Hitchcock.

https://www.docdroid.net/WundFZl/adolf-hitler-mein-kampf-reynal-hitchcock-1941.pdf#page=774

Hofkirchner, Wolfgang. 2016. "Ethics from systems: Origin, development and current state of

normativity." In Morphogenesis and the Crisis of Normativity edited by Margaret Archer pp. 279-295.

Dordrecht: Springer.

MacNair, Rachel M. 2002. "Perpetration-induced traumatic stress in combat veterans." Peace and

Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology 8 (1): 63-72.

Pilgrim, David. 2018a. "Reclaiming reality and redefining realism: the challenging case of

transgenderism." Journal of Critical Realism 17 (3): 308-324.

Pilgrim, David. 2018b. "The transgender controversy: a reply to Summersell." Journal of Critical

Realism 17 (5): 523-528.

Pitts, Barbara L., Paula Chapman, Martin A. Safer, Brian Unwin, Charles Figley, and Dale W. Russell.

2013. "Killing versus witnessing trauma: Implications for the development of PTSD in combat

medics." Military Psychology 25 (6): 537-544.

Plumwood, Val. 1991. "Nature, self, and gender: Feminism, environmental philosophy, and the

critique of rationalism." Hypatia 6 (1): 3-27.

Plumwood, Val. 2002. Feminism and the Mastery of Nature. London: Routledge.

Powell, Tia, and Edward Stein. 2014. "Legal and ethical concerns about sexual orientation change

efforts." Hastings Center Report 44 (s4): S32-S39.

Price, Leigh. 2014. "Hume’s two causalities and social policy: moon rocks, transfactuality, and the

UK’s policy on school absenteeism." Journal of Critical Realism 13 (4): 385-398.

17

�Price, Leigh. 2017. "Wellbeing research and policy in the UK: questionable science likely to entrench

inequality." Journal of Critical Realism 16 ( 5): 451-467.

Summersell, Jason. 2018a. "Trans women are real women: a critical realist intersectional response to

Pilgrim." Journal of Critical Realism 17 (3): 329-336.

Summersell, Jason. 2018b."The transgender controversy: second response to Pilgrim." Journal of

Critical Realism 17 (5): 529-545.

White, Kevin. 2002. An Introduction to the Sociology of Health and Illness. London: SAGE.

18

�

Leigh Price

Leigh Price