Page 1

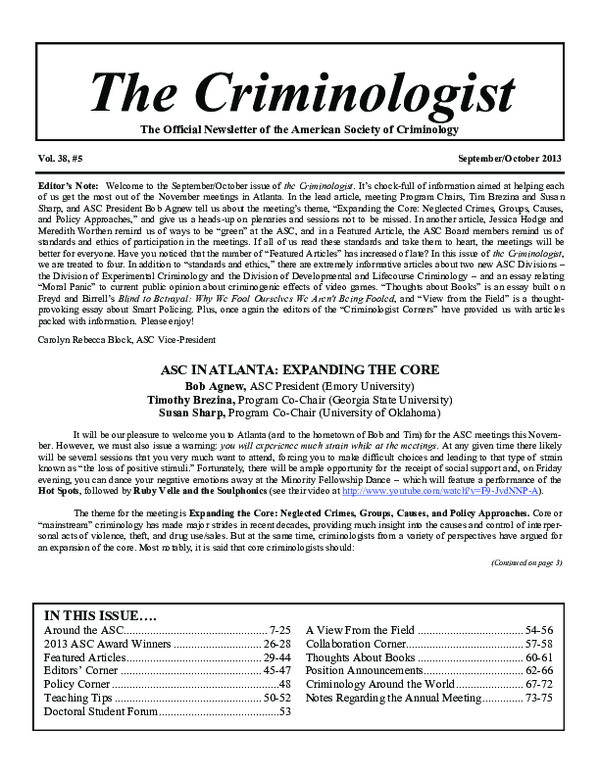

The Criminologist

The Criminologist

The Official Newsletter of the American Society of Criminology

Vol. 38, #5

September/October 2013

Editor’s Note: Welcome to the September/October issue of the Criminologist. It’s chock-full of information aimed at helping each

of us get the most out of the November meetings in Atlanta. In the lead article, meeting Program Chairs, Tim Brezina and Susan

Sharp, and ASC President Bob Agnew tell us about the meeting’s theme, “Expanding the Core: Neglected Crimes, Groups, Causes,

and Policy Approaches,” and give us a heads-up on plenaries and sessions not to be missed. In another article, Jessica Hodge and

Meredith Worthen remind us of ways to be “green” at the ASC, and in a Featured Article, the ASC Board members remind us of

standards and ethics of participation in the meetings. If all of us read these standards and take them to heart, the meetings will be

better for everyone. Have you noticed that the number of “Featured Articles” has increased of late? In this issue of the Criminologist,

we are treated to four. In addition to “standards and ethics,” there are extremely informative articles about two new ASC Divisions –

the Division of Experimental Criminology and the Division of Developmental and Lifecourse Criminology – and an essay relating

“Moral Panic” to current public opinion about criminogenic effects of video games. “Thoughts about Books” is an essay built on

Freyd and Birrell’s Blind to Betrayal: Why We Fool Ourselves We Aren't Being Fooled, and “View from the Field” is a thoughtprovoking essay about Smart Policing. Plus, once again the editors of the “Criminologist Corners” have provided us with articles

packed with information. Please enjoy!

Carolyn Rebecca Block, ASC Vice-President

ASC IN ATLANTA: EXPANDING THE CORE

Bob Agnew, ASC President (Emory University)

Timothy Brezina, Program Co-Chair (Georgia State University)

Susan Sharp, Program Co-Chair (University of Oklahoma)

It will be our pleasure to welcome you to Atlanta (and to the hometown of Bob and Tim) for the ASC meetings this November. However, we must also issue a warning: you will experience much strain while at the meetings. At any given time there likely

will be several sessions that you very much want to attend, forcing you to make difficult choices and leading to that type of strain

known as “the loss of positive stimuli.” Fortunately, there will be ample opportunity for the receipt of social support and, on Friday

evening, you can dance your negative emotions away at the Minority Fellowship Dance – which will feature a performance of the

Hot Spots, followed by Ruby Velle and the Soulphonics (see their video at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F9-JvdNNP-A).

The theme for the meeting is Expanding the Core: Neglected Crimes, Groups, Causes, and Policy Approaches. Core or

“mainstream” criminology has made major strides in recent decades, providing much insight into the causes and control of interpersonal acts of violence, theft, and drug use/sales. But at the same time, criminologists from a variety of perspectives have argued for

an expansion of the core. Most notably, it is said that core criminologists should:

(Continued on page 3)

IN THIS ISSUE….

Around the ASC................................................. 7-25

2013 ASC Award Winners .............................. 26-28

Featured Articles .............................................. 29-44

Editors’ Corner ................................................ 45-47

Policy Corner .........................................................48

Teaching Tips .................................................. 50-52

Doctoral Student Forum.........................................53

A View From the Field .................................... 54-56

Collaboration Corner........................................ 57-58

Thoughts About Books .................................... 60-61

Position Announcements.................................. 62-66

Criminology Around the World ....................... 67-72

Notes Regarding the Annual Meeting .............. 73-75

�Page 2

Vol. 38, No. 5, September/October 2013

UPCOMING CONFERENCES AND WORKSHOPS

Th e C r im ino lo gis t

For a complete listing see www.asc41.com/caw.html

5th ANNUAL INTERNATIONAL CRIME, MEDIA AND POPULAR

CULTURE STUDIES CONFERENCE: A CROSS DISCIPLINARY

EXPLORATION, September 23, 24, and 25, 2013, Indiana State University. For further Information, abstract submission and registration go to:http://

www.indstate.edu/ccj/popcultureconference/.

Th e Offici a l News let t er of th e

Am eri can Soci et y of C ri min ology

THE CRIMINOLOGIST (ISSN 0164-0240) is published six times annually – in January, March, May, July, September, and November by the

American Society of Criminology, 1314 Kinnear Road, Suite 212, Columbus, OH 43212-1156 and additional entries. Annual subscriptions to

non-members: $50.00; foreign subscriptions: $60.00; single copy:

$10.00. Postmaster: Please send address changes to: The Criminologist,

1314 Kinnear Road, Suite 212, Columbus, OH 43212-1156. Periodicals

postage paid at Toledo, Ohio.

AUSTRALIAN AND NEW ZELAND SOCIETY OF CRIMINOLOGY

CONFERENCE (ANZSOC), October 1 - 3, 2013, Brisbane, Queensland,

Australia. Please visit http://www.griffith.edu.au/conference/australian-new

Editor: Carolyn Rebecca Block

-zealand-society-criminology-conference-2013 for more information.

Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority, Retired

34th CANADIAN CONGRESS OF CRIMINAL JUSTICE, 21st CEN- Published by the American Society of Criminology, 1314 KinTURY JUSTICE: THE ECONOMICS OF PUBLIC SAFETY near Road, Suite 212, Columbus, OH 43212-1156. Printed by

October 2 - 5, 2013, Vancouver, Canada. Please visit http://www.ccja- Lesher Printers.

acjp.ca/cong2013/en/cong_2013_call.pdf for more information.

Inquiries:

Address all correspondence concerning newsletter

11TH INDO PACIFIC ASSOCIATION OF LAW, MEDICINE AND materials and advertising to American Society of Criminology,

SCIENCE CONGRESS (INPALMS 2013), October 5-10, 2013. Malaysia. 1314 Kinnear Road, Suite 212, Columbus, OH 43212-1156,

(614) 292-9207, aarendt@asc41.com.

Please visit http://inpalms.org/ for more information.

2ND INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON FORENSIC RESEARCH & TECHNOLOGY, October 7 - 9, 2013, Las Vegas, Nevada.

Please visit http://www.omicsgroup.com/conferences/forensic-technology2013/ for more information.

ASC President: ROBERT AGNEW

Department of Sociology

Emory University

1555 Dickey Drive , Tarbutton Hall

Atlanta, GA 30322

Membership: For information concerning ASC membership,

WORLD CONGRESS ON PROBATION, October 8 - 10, 2013, London, contact the American Society of Criminology, 1314 Kinnear

United Kingdom. Please visit http://www.worldcongressonprobation.org Road, Suite 212, Columbus, OH 43212-1156, (614) 292-9207;

FAX (614) 292-6767; asc@asc41.com; http://www.asc41.com

for more information.

27th ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE AMERICAN EVALUATION ASSOCIATION, October 16 - 19, 2013

Washington, DC. Theme: Evaluation Practice in the Early 21st Century. Please visit http://www.eval.org/eval2013/default.asp for

more information.

EURASIAN MULTIDISCIPLINARY FORUM, October 24 - 26, 2013, Tbilisi, Georgia. Please send your papers via email:contact@emforum.eu . Visit the website at http://www.emforum.eu/.

HOW TO ACCESS CRIMINOLOGY AND CRIMINOLOGY & PUBLIC POLICY ON-LINE

1. Go to the Wiley InterScience homepage - http://www3.interscience.wiley.com

2. Enter your login and password.

Login: Your email address

Password: If you are a current ASC member, you will have received this from Wiley; if not or if you have forgotten

your password, contact Wiley at: cs-membership@wiley.com; 800-835-6770

3. Click on Journals under the Browse by Product Type heading.

4. Select the journal of interest from the A-Z list.

For easy access to Criminology and/or CPP, save them to your profile. From the journal homepage, please click on “save journal

to My Profile”.

If you require any further assistance, contact Wiley Customer Service at cs-membership@wiley.com; 800-835-6770

�Page 3

The Criminologist

(Continued from page 1)

Devote more attention to harmful acts beyond those legally defined as crimes, including acts committed by states.

Consider additional causes of crime, beyond those social psychological factors that dominate core research, with some

arguing for more focus on bio-psychological factors and others on societal characteristics.

More fully consider the ways in which gender, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation and others factors relate to crime;

including victimization and the nature and experience of those factors that cause crime.

Examine crime in non-Western as well as Western societies.

More directly involve themselves in efforts to control crime, better communicating their research findings to the public

and policy makers, working more closely with practitioners, and studying the implementation of programs and policies.

The two plenary sessions at the meetings will highlight the program theme, as well as reflect Atlanta’s reputation as the

“cradle of the Civil Rights Movement.”

The opening plenary on Wednesday at 11 AM will feature Ambassador Andrew Young, one of the principal lieutenants to

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.; Congressman; Ambassador to the United Nations; Mayor of Atlanta; and now co-chair of Good Works

International.

The closing plenary on Saturday at 11:30 AM will feature Congressman John Lewis, who as Chair of the Student

Nonviolent Coordinating Committee helped organize many of the key activities of the Civil Rights Movement – including the march

across the Edmund Pettus Bridge that culminated in the brutal confrontation known as “Bloody Sunday” (and left John Lewis

severely injured).

Congressman Lewis has served in Congress since 1986, where he has developed a reputation as “the conscience of the U.S.

Congress.” And, despite more than 40 arrests and numerous attacks, he has remained a lifelong advocate of nonviolence. He will

receive the President’s Justice Award at his presentation.

The remarks of Ambassador Young and Congressman Lewis will likely reflect several aspects of the Program Theme,

including the need to focus on human rights violations and state crimes, devote more attention to non-Western societies, become

more involved in the policy arena, and more fully consider race/ethnicity, gender and other factors in our studies.

In addition, there will be ten Presidential Panels, with panelists discussing why it is important for criminologists to expand

the core in the ways indicated, highlighting key research/action that has already been done, and discussing needed research/action.

Many of the panel presentations will be made available on the ASC website after the meetings. The panels and their organizers/

presenters are:

Reconsidering the Definition of Crime: Dawn Rothe, Raymond Michalowski, Ronald Kramer, and David Friedrichs.

The Future of Biosocial Criminology: John Wright, David P. Farrington, Kevin M. Beaver, and Adrian Raine.

Gender and Crime: Joanne Belknap, Beth Richie, and Juanita Diaz-Cotto.

Race, Ethnicity, and Crime: Elijah Anderson, Ruth D. Peterson, and Paul Elam.

Situating Crime in Macro-Social and Historical Context: Steve Messner, Charles R. Tittle, Susanne Karstedt, and Randolph

Roth.

Non-Western Crime and Justice: John Braithwaite, Jan von Dijk, and Mangai Natarajan.

Analyzing Crime and the State: John Hagan, Geoff Ward, Nicole Rafter, Christopher Uggen, Suzy McElrath, and Hollie Nyseth

Brehm.

The Emergence of Green Criminology: Nigel South, Rob White, and Ragnhild Sollund.

Key Perspectives in Critical Criminology: Donna Selman, Meda Chesney-Lind, Walter S. DeKeseredy, and Jeff Ferrell.

The ASC and Public Policy: Todd Clear, Laurie Robinson, Charles Wellford, Steve Mastrofski, and James Lynch.

There will be many other special sessions and events at the meetings, a few of which are highlighted below-- particularly

those organized in conjunction with the President, Board, and Program Committee.

Pre-conference Methods Workshops (Tuesday 1-5; see the ASC website, Annual Meeting Info.):

Accomplishing and Interpreting Qualitative Interview Research (Jody Miller and Kristin Carbone-Lopez),

Strategies for Dealing with Missing Data (Robert Brame), and

Item Response and Graded Response Models (Gary Sweeten).

(Continued on page 4)

�Page 4

Vol. 38, No. 5, September/October 2013

(Continued from page 3)

New Member Welcome and Mentoring Reception (Wednesday at 2), cosponsored by the Student Affairs and Mentoring Committees, where

new members will be welcomed by ASC officers and others,

an orientation to the meetings will be provided,

and there will be ample opportunity for socializing with new and longtime ASC members.

Numerous sessions involving key figures in the policy arena, including

National Institute of Justice Director, Greg Ridgeway;

Bureau of Justice Statistics Director, William Sabol; and

a Meet and Greet Session with the Assistant Attorney General for the Office of Justice Programs, Karol Mason

(AAG Mason oversees all Department of Justice agencies dealing with crime research, statistics, and policy).

Meet the President and President Elect.

Each year the ASC holds a business meeting, as required by law, and almost no one attends. This year we are combining the business

meeting with an opportunity to meet with the President and President Elect. Joanne Belknap and I will be there, not to make presentations, but to hear your concerns, take note of your suggestions, and answer your questions. Assuming that attendance is good, we

hope that this becomes an annual tradition – increasing the responsiveness and transparency of the ASC.

Wednesday evening ASC Awards Ceremony, featuring an address by Cathy Spatz Widom, who is receiving the Edwin H. Sutherland Award for her seminal work on child abuse and neglect and its consequences.

Session Honoring the 2013 Sellin-Glueck Award Winner, Clifford Shearing, known for his work on policing and security in

South Africa and cross nationally, and featuring Clifford Shearing, Jennifer Wood, Benoit Dupont, and Peter Manning.

Freda Adler: A Tribute, featuring presentations by Francis T. Cullen, Pamela Wilcox, Alido V. Merlo, Jay S. Albanese, and, of

course, Freda Adler.

Session on Expanding the Horizons of Criminology: The Intellectual Contributions of Gilbert Geis, featuring presentations by

Sally S. Simpson, John Braithwaite, Henry N. Pontell, Robert F. Meier, Mary Dodge, and Robert Agnew.

Session on whether the ASC should develop an Ethics Code (“ASC Ad Hoc Ethics Code Investigation Committee”), featuring

Nancy Rodriguez, Barry Feld, Vernetta Young, Marjorie Zatz, Cassia Spohn, and Mark Davis.

Session on issues in publishing (“Pressure, Structure, and Ethics: Criminology’s Contemporary Issues in Publishing”), featuring

Volkan Topalli, Wayne Osgood, Cassia Spohn, Beth Huebner, and Robert Bursik.

Friday 5 PM Presidential Address

I will not talk about general strain theory; rather, my address is titled: Social Concern and Crime: Moving beyond the Assumption of Simple Self-Interest. (But my address has implications for strain theory, as suggested by the first sentence in Merton’s classic article, “Social Structure and Anomie.”)

There are many other great sessions at the meetings! We urge you to carefully examine

the Program (even though it is a source of strain).

Local Charity

We are very pleased to continue the ASC tradition of designating a local charity for the annual meeting. Volkan Topalli,

Chair of the Local Arrangements Committee, will shortly provide information on Visions Unlimited, a community-based group that

provides a range of prevention and rehabilitation services in the Atlanta area.

(Continued on page 5)

�Page 5

The Criminologist

(Continued from page 4)

The Marriott Marquis and Atlanta

The meeting will be at the Atlanta Marriot Marquis, a wonderful facility with lots of public space, one of the largest atriums

in world, and an adjacent food court. The Marriott was in the midst of an extensive renovation when the ASC last meant there a few

years ago, but the renovations are now complete. The Marriott is a short distance from the King Center and the attractions of Centennial Olympic Park (e.g., Georgia Aquarium, the world’s largest; the World of Coca Cola, CNN, Skyview Atlanta - a giant Ferris

wheel). There is a new International Terminal at the Atlanta airport, which our many international attendees should appreciate. And

the Marriott Marquis is easily reached from the MARTA (rapid rail) station at the airport; take any train from the airport and get off

at the Peachtree Center stop – the Marquis is on the other side of the Peachtree Center food court. The Local Arrangements Committee will provide more information on the city.

Thanks.

A meeting of this scale, with over 900 sessions, cannot take place without the work of many people. We would like to extend special thanks to Chris Eskridge, who as Executive Director of the ASC performs literally thousands of tasks in putting the

meeting together; the wonderful staff at the Columbus Office, including the ASC Administrator Susan Case; the members of the Program, Awards, and Local Arrangements Committees; Volkan Topalli at Georgia State University; and Charles Wellford, Todd Clear,

and Laurie Robinson, who helped arrange many of the policy activities at the meetings.

CRIME & JUSTICE SUMMER RESEARCH INSTITUTE: BROADENING PERSPECTIVES &

PARTICIPATION

July 7 – 25, 2014, Ohio State University

Faculty pursuing tenure and career success in research-intensive institutions, academics transitioning from teaching to research

institutions, and faculty members carrying out research in teaching contexts will be interested in this Summer Research Institute.

Funded by the National Science Foundation, the institute is designed to promote successful research projects and careers among

faculty from underrepresented groups working in areas of crime and criminal justice. During the institute, participants work to

complete an ongoing project (either a research paper or grant proposal) in preparation for journal submission or agency funding

review. In addition, participants gain information that serves as a tool-kit tailored to successful navigation of the academic

setting. To achieve these goals the Summer Research Institute provides participants with:

- Resources for completing their research projects;

- Senior faculty mentors in their areas of study;

- Opportunities to network with junior and senior scholars;

- Workshops addressing topics related to publishing, professionalization, and career planning;

- Travel expenses to Ohio, housing in Columbus, and living expenses.

The institute culminates in a research symposium where participants present their completed research before a national audience.

Dr. Ruth D. Peterson directs the Crime and Justice Summer Research Institute, which is held at Ohio State University’s Criminal

Justice Research Center (Dr. Dana Haynie, Director) in Columbus, Ohio.

Completed applications must be sent electronically by Friday, February 14, 2014. To download the application form, please

see our web site (http://cjrc.osu.edu/rdcj-n/summerinstitute). Once completed, submit all requested application materials to

kennedy.312@sociology.osu.edu. All applicants must hold regular tenure-track positions in U.S. institutions and demonstrate

how their participation broadens participation of underrepresented groups in crime and justice research. Graduate students

without tenure track appointments are not eligible for this program. Please direct all inquiries to

kennedy.312@sociology.osu.edu.

�Page 6

Vol. 38, No. 5, September/October 2013

GRADUATE PROGRAMS IN CRIMINAL JUSTICE

AT THE UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI

Master of Science Program

Distance Learning Master of Science Program

Ph.D. Program

Main Areas of Specialization:

Corrections, Crime Prevention, Criminal Justice, Criminology, Policing

For more information, please visit our website at:

www.uc.edu/criminaljustice

The Faculty

Michael L. Benson (University of Illinois) White-Collar Crime; Criminological Theory; Life-Course Criminology

Susan Bourke (University of Cincinnati) Corrections; Undergraduate Retention; Teaching Effectiveness

Sandra Lee Browning (University of Cincinnati) Race, Class, and Crime; Law and Social Control; Drugs and Crime

Aaron J. Chalfin (University of California, Berkeley) Criminal Justice Policy; Economics of Crime; Research Methods

Nicholas Corsaro (Michigan State University) Policing, Environmental Criminology, Research Methods

Francis T. Cullen (Columbia University) Criminological Theory; Correctional Policy; White-Collar Crime

John E. Eck (University of Maryland) Crime Prevention; Problem-Oriented Policing; Crime Pattern Formation

Robin S. Engel (University at Albany, SUNY) Policing; Criminal Justice Theory; Criminal Justice Administration

Ben Feldmeyer (Pennsylvania State University) Race/Ethnicity, Immigration, and Crime; Demography of Crime; Methods

Bonnie S. Fisher (Northwestern University) Victimology/Sexual Victimization; Public Opinion; Methodology/Measurement

James Frank (Michigan State University) Policing; Legal Issues in Criminal Justice; Program Evaluation

Edward J. Latessa (The Ohio State University) Rehabilitation; Offender/Program Assessment; Community Corrections

Sarah M. Manchak (University of California, Irvine) Correctional interventions, Risk Assessment and Reduction, Offenders

with Mental Illness

Joseph L. Nedelec (Florida State University) Biosocial Criminology; Evolutionary Psychology; Life-Course Criminology

Paula Smith (University of New Brunswick) Correctional Interventions; Offender/Program Assessment; Meta-Analysis

Christopher J. Sullivan (Rutgers University) Developmental Criminology, Juvenile Prevention Policy, Research Methods

Lawrence F. Travis, III (University at Albany, SUNY) Policing; Criminal Justice Policy; Sentencing

Patricia Van Voorhis (University at Albany, SUNY; Emeritus) Correctional Rehabilitation and Classification; Psychological

Theories of Crime; Women and Crime

Pamela Wilcox (Duke University) Criminal Opportunity Theory; Schools, Communities, and Crime, Victimization/Fear of

Crime

John D. Wooldredge (University of Illinois) Institutional Corrections; Sentencing; Research Methods

John P. Wright (University of Cincinnati) Life-Course Theories of Crime; Biosocial Criminology; Longitudinal Methods

Roger Wright (Chase College of Law) Criminal Law and Procedure; Policing; Teaching Effectiveness

�Page 7

The Criminologist

AROUND THE ASC

KRISTEN M. ZGOBA WINS THE PETER P. LEJINS RESEARCH AWARD

Congratulations to Kristen Zgoba on winning the prestigious Peter P. Lejins Research Award, the highest honor bestowed

upon a corrections researcher! Currently the supervisor of research and evaluation at the New Jersey Department of Corrections, Dr.

Zgoba’s accomplishments include “benchmark” research on the prevalence of sex offenses before and after Megan’s Law (see

https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/225402.pdf), followed by a number of other projects on the characteristics of sex offenders, predictive validity of risk assessment tools, recidivism trajectories, and collateral consequences of sex offender notification and residency restriction laws.

Given by the American Corrections Association in honor of Peter P. Lejins “a distinguished research professor whose work

has influenced the world of corrections and criminal justice for more than 50 years,” Lejins Award winners have “produced significant research for the correctional community and . . . demonstrated personal commitment and contribution to improve the profession

of corrections.” For more information, see http://www.aca.org/pastpresentfuture/awards.asp.

SUCCESSFUL STOCKHOLM SYMPOSIUM!

The eighth annual Stockholm Criminology Symposium was held in Stockholm, Sweden in June. Over 600 delegates from

over 44 countries had signed up to take part in the Symposium.

The three day event was filled with more than 200 presentations covering a variety of topics under the main tracks: Saved

from a life of crime: Evidence-based crime prevention and Contemporary criminology. Researchers, practitioners and policymakers

from all over the world shared their knowledge and experiences and took the opportunity to meet new and old colleagues.

The Swedish Minister for Justice, Beatrice Ask participated in the inaugural discussion. Other participants were the winner

of the Stockholm Prize in Criminology 2013, David Farrington (UK) along with Frances Gardner (UK) and Martin Killias

(Switzerland). The panel was moderated by Leena Augimeri (Canada).

The Stockholm Prize in Criminology was presented to David Farrington by the Swedish Minister for Justice, Beatrice Ask.

The prize ceremony and gala dinner was held in the City Hall in Stockholm.

The next Stockholm Criminology Symposium takes place in June 2014 in Stockholm, Sweden. Please visit the symposium

website for more information about dates, call for papers etc. The symposium website also contains articles and video clips from the

2013 symposium. www.criminologysymposium.com

INTERVIEW A PROFESSIONAL

The Social Studies program at Sutton Memorial High School (Sutton, Massachusetts) is requiring students to interview professionals in different career fields. If you are interetsed in participating, go to: https://www.surveymonkey.com/s/CRIMe-Pals

�Page 8

Vol. 38, No. 5, September/October 2013

AROUND THE ASC

LET’S BE GREEN IN ATLANTA!

Meredith Worthen, University of Oklahoma

Jessica Hodge, University of Missouri-Kansas City

As we get closer to the annual meeting in Atlanta, we would like to remind you of two exciting innovations that will be

implemented:

A smaller printed program due to less white space and smaller margins.

An app (i.e. application software for mobile devices) for accessing the program in a friendly, searchable format. Information

for access will be in your meeting bag.

Please note that meeting attendees will get their choice – paper, app, or both.

We also encourage attendees to reuse old ASC name badge holders by simply bringing one with you from a previous

conference; this could also be done with ASC bags.

We hope that meeting attendees will continue to choose these green options at future ASC meetings. If you would like

to share other ideas for how we can all make ASC even greener, please email Meredith Worthen at mgfworthen@ou.edu or Jessica Hodge at hodgejp@umkc.edu or join the discussion on Facebook (search for the title of the group, “Recycling is Not a

Crime group at ASC”).

�Page 9

The Criminologist

AROUND THE ASC

NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION SEEKING PROPOSALS

The National Science Foundation (NSF) is interested in receiving proposals to existing programs in any directorate across the

Foundation that address fundamental research questions which might simultaneously advance activities related to research and

education in forensic sciences. Supplement requests to existing awards may also be submitted. For more information, see http://

www.nsf.gov/pubs/2013/nsf13120/nsf13120.pdf

MENTORING AT CAREERVILLAGE.ORG

CareerVillage.org is a non-profit organization that helps high school students living in low-income communities to obtain educational and career advice online from working professionals. By volunteering to give advice, professionals help young people

make critical decisions about college and careers. If you wish to participate as a professional mentor to low-income high school

students, you may sign up at www.careervillage.org

WESTERN SOCIETY OF CRIMINOLOGY CONFERENCE

In February, 2014, the Western Society of Criminology (WSC) will hold its annual meeting at the Ala Moana Hotel in

Honolulu, Hawaii. This hotel offers accommodations with stunning mountain views or beautiful sunsets over the ocean. Their

professional meeting rooms will accommodate this year’s panels focusing on topics including: Legal Issues in Criminal Justice;

Criminological Theory; Crime Analysis; Terrorism; White-Collar Crime; Cybercrime; and Sex Crimes. Abstracts of no more

than 1,100 characters are due by October 4, 2013. Conference registration includes admission into our awards luncheon honoring

outstanding professionals working in criminology and criminal justice; and an enjoyable brunch allowing participants to connect

with friends and colleagues. If you have questions about the WSC conference, please contact our program co-chairs: Dr. Ryan

Fischer at Ryan.Fischer@csulb.edu or Dr. Samantha Smith-Pritchard at sam.smith.phd@gmail.com or visit the WSC web page at

www.westerncriminology.org. The WSC is also a student-friendly organization with two awards for students to consider: 1) The

June Morrison Scholarship Fund which provides supplemental funds to support student member participation at the annual conference; and 2) The Miki Vohryzek-Bolden (MVB) Student Paper Competition which recognizes excellent student work including, but not limited to, policy analyses and original research. Additional details about these awards can be found on the WSC web

page. All conference participants need to make reservations by January 6, 2014. Information about the Ala Moana Hotel can be

found on the hotel website (www.alamoanahotelhonolulu.com) or by calling 808-955-4811. We are looking forward to seeing

you in paradise!

CONGRESSIONAL LUNCHEON ON CRIMINOLOGY, CAUSALITY, AND PUBLIC POLICY

A Congressional Luncheon focused on the topic of criminology, causality, and public policy (the theme of the November 2013 Special Issue of Criminology & Public Policy) will be held on Tuesday, November 12, 2013 in the U.S. Capitol Visitor

Center. The session is being co-sponsored by the American Society of Criminology (ASC), Wiley-Blackwell Publishing, and the

Consortium of Social Science Associations (COSSA).

The luncheon and special issue will address how best to advance criminal justice policy in the absence of causal certainty while simultaneously employing rigorous standards of scientific methodology and best available knowledge. Recommendations will be validated with examples from three criminal justice policy initiatives, namely, delinquency prevention, policing, and

supermax prisons.

The program will proceed as follows:

Introduction: Thomas G. Blomberg, Julie Mestre, and Karen Mann

Presentation: Robert J. Sampson, Christopher Winship, and Carly Knight

Policy Response: Abigail Fagan

Policy Response: Daniel S. Nagin and David Weisburd

Policy Response: Daniel P. Mears

Conclusions: Alfred Blumstein

�Page 10

Vol. 38, No. 5, September/October 2013

AROUND THE ASC

RECENT PhD GRADUATES

Allen, Andrea, “Policing Alcohol and Related Crimes on Campus.” Chaired by Geoffrey P. Alpert, June 2013, University of

South Carolina

Barrett, Kimberly, “Assessing the Relationship between Hotspots of Lead and Hotspots of Crime.” Chaired by Michael J.

Lynch, May 2013, University of South Florida.

Bell, Valerie, “Gender-Responsive Risk Assessment: A Comparison of Women and Men.” Chaired by Dr. Patricia Van Voorhis,

June 2012, University of Cincinnati.

Brushett, Rachel, “Typologies of Female Offenders: A Latent Class Analysis Using the Women’s Risk Needs Assessment.”

Chaired by Dr. Patricia Van Voorhis, Spring 2013, University of Cincinnati.

Carter, David, “A Meta-analysis of Early Life Influences on Behavior.” Chaired by Dr. John Wright, Au gust 2012, University

of Cincinnati.

Donner, Chris, “Examining the Link between Self-control and Misconduct in a Multi-agency Sample of Police Supervisors: A

Test of Two Theories.” Chaired by Lorie Fridell, May 2013, University of South Florida.

Flores, Anthony, “Examining the Youth Level of Service/Case Management Inventory in the Context of Re liability, Validity,

Equity, and Utility: A Six-Year Evaluation.” Chaired by Dr. Edward Latessa, August 2013, University of Cincinnati.

Fox, Andrew, "Examining Gang Social Network Structure and Criminal Behavior," Chaired by Charles Katz, May 2013, Arizo

na State University.

Goulette, Natalie, “Are Female Defendants Treated More Leniently by Judges? A Multilevel Analysis of Sex-Based Dispari

ties at the Phases of Pretrial Release, Charge Reductions, and Sentencing.” Chaired by Dr. John Wooldredge, August

2013, University of Cincinnati.

Kirkland-Gillespie, Amelia, “Rurality and Intimate Partner Homicide: Exploring the Relationship between Place, Social Struc

ture, and Femicide in North Carolina.” Chaired by Dwayne Smith, May 2013, University of South Florida.

Kodellas, Spyridon, “Victimization, Fear of Crime, and Perception of Risk in the Workplace: Testing Rival Theories with a

Sample of Greek and Creek-Cypriot journalists.” Chaired by Dr. Bonnie Sue Fisher, December 2012, University of Cin

cinnati.

Larson, Matthew, "Romantic Dissolution and Offending During Emerging Adulthood,"Chaired by Gary Sweeten, May 2013,

Arizona State University.

Lovins Brusman, Lori, “An Empirical Examination of Variation in Effective Correctional Program Characteristics by Gender.”

Chaired by Dr. Edward Latessa, June 2013, University of Cincinnati.

Lovins, Brian, “Putting Wayward Kids Behind Bars: The Impact of Length of Stay in Custodial Setting on Recidivism.” Chaired

by Dr. Edward Latessa, June 2013, University of Cincinnati.

Lytle, Daniel, “Decision Making in Criminal Justice Revisited: Toward a General Theory of Criminal Justice.” Chaired by

Lawrence Travis, June 2013, University of Cincinnati.

McGuffog, Ingrid D., "Drug Use and Drug Control Policy: Evaluating the Impact of Precursor Chemical Control on Drug User

Behavior."Co-Chaired by Assoc Professor Janet Ransley and Professor Lorraine Mazerolle, August 2013, Griffith Uni

versity.

Miles-Johnson, Toby, "Policing Gender Diversity: Perceptions of Intergroup Difference between Police and Transgender Peo

ple,"Chaired by Professor Lorraine Mazerolle, April 2013, University Of Queensland.

�Page 11

The Criminologist

AROUND THE ASC

RECENT PhD GRADUATES (Cont.)

Monk, Kadija, “How Central Business Districts Manage Crime and Disorder: A Case Study in the Processes of Place Manage

ment in Downtown Cincinnati.” Chaired by Dr. John Eck, June 2012, University of Cincinnati.

Newsome, Jamie, “Resilience and Vulnerability in Adolescents at Risk for Delinquency: A Behavioral Genetic Study of Differen

tial Response to Risk.” Chaired by Dr. John Wright, June, 2013, University of Cincinnati.

Pinchevsky, Gillian, “Assessing the impact of the court response to domestic violence in two neighboring counties.” Chaired by

Emily M. Wright and Jeff Rojek (co-chair), July 2013, University of South Carolina.

Reitler, Anglea, “A Mixed-Methodological Exploration of Potential Confounders in the Study of the Causal Effect of Detention

Status on Sentence Severity in One Federal Court.” Chaired by Dr. James Frank, August 2013, University of Cincinnati.

Schaefer, Lacey, “Environmental Corrections: Making Offender Supervision Work.” Chaired by Dr. Francis Cullen, August

2013, University of Cincinnati.

Sellers, Brian, “Zero Tolerance for Marginal Populations: Examining Neoliberal Social Controls in American Schools.”

Chaired by Michael J. Lynch and Wilson Palacios, July 2013, University of South Florida.

Swartz, Kristin, “Code of the Hallway: Examining the Contextual Effects of School Subculture on Violence, Sexual Offending

and Non-Violent Delinquency.” Chaired by Dr. Pamela Wilcox, August 2012, University of Cincinnati.

Taylor, Melanie, "A Case Study of the Civil Rights of Institutionalized Persons Act: Reforming the Arizona Department of Cor

rections,"Chaired by Scott Decker, Arizona State University.

Valadez, Mercedes, "We have got enough criminals in the United States without importing any:"An Examination of the Influence

of Citizenship Status, Legal Status, and National Origin Among Latino Subgroups in Federal Sentencing Out

comes, Chaired by Cassia Spohn, Arizona State University.

Webster, Jennifer, “A Meta-Analytic Review of the Correlates of Job Stress Among Police Officers.” Chaired by Dr. Lawrence

Travis, August 2012, University of Cincinnati.

�Page 12

Vol. 38, No. 5, September/October 2013

Call for Nominations for the 2013 Division on

Women and Crime Awards

Nominations are requested for the following Division on Women and Crime awards:

Distinguished Scholar Award which recognizes outstanding contributions to the field of women and crime by an

established scholar. The contributions may consist of a single outstanding book or work, a series of theoretical or

research contributions, or the accumulated contributions of an established scholar. Eligibility includes scholars who

have held a Ph.D. for eight or more years.

New Scholar Award which recognizes the achievements of scholars who show outstanding merit at the beginnings

of their careers. Outstanding merit may be based on a single book or work, including dissertation or a series of theoretical or research contributions to the area of women and crime. Eligibility includes scholars who held a Ph.D. for

less than eight years.

Lifetime Achievement Award which recognizes scholars upon retirement. We inaugurated this award on our 20th

Anniversary, 2004. Scholars receiving this award should have an established career advancing the goals and work of

the Division on Women and Crime.

CoraMae Richey Mann “Inconvenient Woman of the Year” Award recognizes the scholar/activist who has participated in publicly promoting the ideals of gender equality and women’s rights throughout society, particularly as it

relates to gender and crime issues. This award will be granted on an ad hoc basis. Nominations should include specific documentation of public service (news articles, etc) and should describe in detail how this person’s activism has

raised awareness and interest in the issues that concern the Division on Women and Crime. This award was inaugurated in honor of our 20th Anniversary in 2004.

Saltzman Award for Contributions to Practice

The Saltzman Award for Contributions to Practice recognizes a criminologist whose professional accomplishments

have increased the quality of justice and the level of safety for women. The Saltzman Award need not be given every

year. It is available to honor unique achievements combining scholarship, persuasion, activism and commitment, particularly work that has made a deep impact on the quality of justice for women, as well as a wide impact

(interdisciplinary, international, or cross-cultural).

Graduate Scholar Award

The Graduate Scholar Award recognizes the outstanding contributions of graduate students to the field women and

crime, both in their published work and their service to the Division of Women & Crime. Outstanding contributions

may include single or multiple published works that compliment the mission of the DWC, and significant work within the Division, including serving as committee members, committee chairs, or executive board members. Preference

will be given to those candidates who have provided exceptional service to the DWC. Eligibility includes scholars

who are still enrolled in an M.A. or Ph.D. program at the time of their nomination.

�Page 13

The Criminologist

Sarah Hall Award

The Sarah Hall Award (established in 2012) recognizes outstanding service contributions to the Division on Women

and Crime of the American Society of Criminology and to professional interests regarding feminist criminology. Service may include mentoring, serving as an officer of the Division on Women and Crime, committee work for the

ASC, DWC, or other related group, and/or serving as editor or editorial board member of journals and books or book

series devoted to research on women and crime. The award is named after Sarah Hall, administrator of the American

Society of Criminology for over 30 years, whose tireless service helped countless students and scholars in their careers.

Submission Information

The nominees are evaluated by the awards committee based on their scholarly work, their commitment to women in

crime as a research discipline, and their commitment to women in crime as advocates, particularly in terms of dedication to the Division on Women and Crime. In submitting your nomination, please provide the following supporting

materials: a letter identifying the award for which you are nominating the individual and evaluating a nominee’s contribution and its relevance to the award, the nominee’s c.v. (short version preferred). No nominee will be considered

unless these materials are provided and arrive by the deadline. The committee reserves the right to give no award in a

particular year if it deems this appropriate.

Send nominations and supporting materials by October 8, 2013 to:

Carrie Buist

Assistant Professor

University of North Carolina Wilmington

601 South College Road

Wilmington, NC 28403

buistc@uncw.edu

carriebuist@gmail.com

**Electronic Submissions are preferred, but not necessary

**Gmail account is preferred for nomination materials carriebuist@gmail.com

**Please visit http://www.asc41.com/dir4/awards.html for a list of past award winners

�Page 14

Vol. 38, No. 5, September/October 2013

American Society of Criminology

2013 Division on Women and Crime Student Paper Competition

The Division on Women and Crime (DWC) of the American Society of Criminology invites submissions for the Student Paper

Competition. The 2012 competition had the highest number of paper submissions in the history of the competition – a total of 25

submissions! The winners will be recognized during the DWC breakfast meeting at the 2013 annual conference in Atlanta. The

graduate student winner will receive $500.00 and the undergraduate student winner will receive $250.00. For submissions with

multiple authors, the award money will be divided among co-authors.

Deadline: Papers should be RECEIVED by the committee chair by September 15, 2013

Eligibility: Any undergraduate or graduate student who is currently enrolled or who has graduated within the previous semester

is eligible. Note, any co-authors must also be students, that is, no faculty co-authors are permitted. To document eligibility, every author/co-author must submit proof of student status. This eligibility proof may be in the form of a letter from your department chair or an unofficial transcript.

Paper Specifications: Papers should be of professional quality and must be about, or related to, feminist scholarship, gender

issues, or women as offenders, victims or criminal justice professionals. Papers must be no longer than 35 pages including all

references, notes, and tables; utilize an acceptable referencing format such as APA; be type-written and double-spaced; and include an abstract of 100 words or less.

Papers may not be published, accepted, or under review for publication at the time of submission.

Submission: One electronic copy using MSWord must be received by the co-chair of the committee by the stated deadline

(please do not send a PDF file). In the reference line, identify whether this is to be considered for the graduate or undergraduate

competition. Please refrain from using identifying (e.g., last name) headers/ footers, as the papers will be blind-reviewed.

Judging: Members of the paper competition committee will evaluate the papers based on the following categories: 1. Content is

relevant to feminist scholarship; 2. Makes a contribution to the knowledge base; 3. Accurately identify any limitations; 4. Analytical plan was well developed; 5. Clarity/organization of paper was well developed.

Notification: All entrants will be notified of the committee’s decision no later than November 1 st. Winners are strongly encouraged to attend the conference to receive their award.

Co-Chairs of Committee:

Email all paper submissions to:

Angela R. Gover, PhD │School of Public Affairs │ University of Colorado Denver│

phone (303)315-2474│angela.gover@ucdenver.edu

For all other correspondence:

Lisa A. Murphy, Ph.D. │ Department of Psychology│La Sierra University│

phone: (951) 272-6300 x1008│ lmurphy@lasierra.edu

�The Division on Corrections and Sentencing

would like to invite you to

join us in Atlanta!

Annual Business Meeting and Awards Breakfast

Thursday, Nov. 21, 8 – 9:20 am.

International C (International Level)

****************************************************

DCS Happy Hour

Note that the event is off-site, and near the hotel

Thursday, Nov. 21, 7-8:30 pm

Max Lager’s Wood Fired Grill & Brewery

320 Peachtree Street

(at the corner of Peachtree St. and West Peachtree St.)

Arrive early for the OPEN BAR!

***************************************************

Look for our hospitality table near the book exhibit.

The DCS is devoted to facilitating scholarship on corrections

and sentencing and to promoting the professional development

of its members.

Dues: $10 for regular members, $5 for students. For more information about the

DCS, visit us our webpage at http://www.asc41.com/dcs

�DIVISION OF EXPERIMENTAL CRIMINOLOGY

AMERICAN SOCIETY OF CRIMINOLOGY

.

Counting down to ASC-Atlanta 2013

CONGRATULATIONS TO OUR AWARD WINNERS!

Division of Experimental Criminology

Academy of Experimental Criminology

Jerry Lee Lifetime Achievement Award

Lawrence Sherman

Joan McCord Award

Lorraine Mazerolle

Award for Outstanding Experimental Field Trial

Jerry Ratcliffe, Travis Taniguchi, Elizabeth

Groff, and Jennifer Wood for “Philadelphia

Foot Patrol Experiment”

AEC Fellows

Robert Davis and Christopher Koper

Student Paper Award

Matthew Nelson, Alese Wooditch, and Lisa

Dario for “A Replication Study of

Weisburd’s Paradox”

Outstanding Young Experimental Criminologist

Award - Justin Ready

DEC

&

aEc

DEC @ ASC-ATLANTA 2013: MEETINGS, AWARDS, AND NEW BOARD

We look forward to seeing everyone at the AEC Joan McCord Award Lecture and the DEC Meet and

Greet and Awards Ceremony in Atlanta on Wednesday, beginning at 2:00 pm on Wednesday, Nov. 20.

To download a one-pager of all panels related to experimental criminology, visit the “DEC at ASC”

webpage at our website: http://cebcp.org/dec/dec-at-asc/.

David Weisburd (Chair), Lynette Feder (Vice Chair), Cynthia Lum (Secretary-Treasurer)

Executive Counselors: Anthony Braga (President of AEC), Geoffrey Barnes, and Elizabeth Groff

JOIN THE DIVISION OF EXPERIMENTAL CRIMINOLOGY: http://cebcp.org/dec

�The ASC and DEC congratulate the Hot

Spots Band for 20 Rockin’ performances!

Wayne

Chris

Steve

Alex

Brenda

Larry

Join the Hot Spots Band, celebrating their

20th ASC performance in Atlanta

Friday, November 22nd at 9pm (Marquis Ballroom)

The American Society of Criminology and its Division of Experimental

Criminology (DEC) thank the Hot Spots Band for 20 years of

wonderful entertainment and their support for the Minority Fellowship

Award. Your performances are always among the highlights of the

Annual Meeting and we greatly appreciate all you have contributed.

TRIVIA!! Can you name all of the ASC performances of the Hot Spots?

For the answer and to learn how you can join the Division of

Experimental Criminology, visit us at http://cebcp.org/dec/hot-spot/

�Please join

The Division on

Critical

Criminology

Thursday, November 21, 2013

Executive Meeting

3:30-4:20 pm

A601 (Atrium Level)

General Business

Meeting

4:30-5:50 pm

A601 (Atrium Level)

Social

6:00-10:00 pm

A601 (Atrium Level)

�AMERICAN SOCIETY OF CRIMINOLOGY

DIVISION OF VICTIMOLOGY

The Division of Victimology (DOV) is one of the newest divisions within the American

Society of Criminology (ASC), and was created to help the field of victimology continue to

evolve and to bring continued attention to the issue of criminal victimization.

The second annual Division of Victimology meeting will be held at the ASC conference on

Wednesday, November 20, 2013 @ 2:00 pm. In addition, there will be a DOV social later

that night at Ma Lager’s on histori Pea htree Street, 5:00-6:30pm. Ma ’s is e iting for

the local craft beer selection, but also for their brick oven pizzas. Don’t worry if you

don’t like eer. They have a full bar and non-alcoholic options as well. The event space

upstairs has plenty of tables and even a pool table. It should be a great space for us to

hang out and socialize informally. If you arrive early enough, you might get a free drink

before DOV funds run out!

Check

out

our

website

(www.ascdov.com)

and

like

us

on

Facebook

(facebook.com/ascdov). For membership information, and to subscribe to the list serve,

please contact Kate Fox (katefox@asu.edu) or Kelly Knight (kelly.knight@shsu.edu).

�Who Are We?

DWC is a collective of persons who believe that the study of women, gender, and crime is

central to criminology. After nearly three decades, and with over 375 members, the DWC is

the oldest Division within the American Society of Criminology.

What Do We Offer?

The DWC facilitates and promotes research and theory development, pedagogical strategies,

and curricular enhancement that strengthen the links between gender, crime, and justice.

The DWC also recognizes the achievements of women as students and professional scholars

in the study of criminology through its annual awards.

To encourage networking and interaction among academics, researchers, practitioners, and

students, the DWC provides a variety of opportunities for professional and social interaction

including: feminist theory and action workshops; specialty workshops and forums; numerous

panels and presentations on gender, crime, and justice; and an annual social.

How Can You Join Us?

Are you interested in issues related to gender and crime, women as professionals, feminist

theory and praxis, and women as victims and/or offenders? Have you ever been in need of a

mentor, career, or school advice, or recommended readings for one of your courses?

Wouldn’t it be great to belong to a supportive professional organization that could meet

these needs while furthering the understanding and remedying of problems that affect

women as professionals, victims, and offenders? Consider joining the Division on Women

and Crime. The Division on Women and Crime (DWC) fulfills these objectives and many

more!

�Find Us at the ASC in Atlanta!

Want to know more about the Division on Women and Crime? Visit our outreach table on

Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday. Also, if you’re in town early, the DWC is hosting its 13th

annual pre-meeting “DWC Feminist Criminology in Theory and Action” workshop on

Tuesday (11/19), from 4:00 - 7:00 PM in M202, Marquis Level. The workshop provides an

opportunity to informally discuss ways to connect our academic work to social change in the

classroom and community.

Please join us at the Division’s annual social on Wednesday (11/20) from 8:00 – 9:30 PM

offsite at Max Lager’s Wood-Fired Grill and Brewery located at 320 Peachtree Street NE (a 5minute walk from the hotel). You can view the venue at maxlagers.com. Purchase your

ticket when you register for the conference or at the door.

Finally, the DWC will be sponsoring two open breakfast meetings on Thursday and Friday.

Thursday’s breakfast meeting (11/21) from 7:30 - 9:00 AM in A601 on the Atrium level will

summarize the work of the DWC and its committees over the past year, plan for the next

year, and announce the 2013 award winners. Friday’s breakfast meeting (11/22) will be held

from 7:30 - 9:00 am (also in A601, Atrium level), and will include focused participatory

discussions of topics of interest to DWC members. Some of last year’s topics included

outreach, concerns of students, conducting feminist research, mentoring, and curriculum

guide revision and networking opportunities for women in non-academic jobs.

Check Out Our Website, Newsletter, & Journal

The DWC remains active and involved with its members all year long through its online

Division newsletter (hts.gatech.edu/dwc), its informative website (ascdwc.com), its

presence in social media, and committee work that strives to support both new and

established members. The newsletter features member news, articles, announcements of

jobs, publications, and funding opportunities, as well as regular “Ask a Tenured Professor,”

“Teaching Tips,” and “Graduate Student Corner” columns.

Feminist Criminology (fcx.sagepub.com) is an innovative journal that is dedicated to

research related to women, girls, and crime within the context of a feminist critique of

criminology.

The DWC listserv is a wonderful forum for members who seek or offer information on career

opportunities or decisions, school selections, curricular development, research, or any

variety of topics related to women, gender, crime, and justice. You can also stay in touch

with the DWC via Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn. Visit ascdwc.com/communication for

details on all the ways you can find us on the world wide web!

�Page 22

Vol. 38, No. 5, September/October 2013

DWC SOCIAL FULL

�Division on People of Color and Crime

Annual Symposium and Awards Luncheon

Thursday, November 21, 2013, 12:30-1:50pm

Sweet Georgia’s Juke Joint

200 Peachtree Street, Atlanta, Georgia 30303

Symposium Keynote Speaker:

http://www.sweetgeorgiasjukejoint.com

Jody E. Owens, II

Southern Poverty Law Center

Tickets must be purchased by

October 1, 2013 via ASC

Jody E. Owens, II is the Director of the Mississippi office of the

conference registration.

Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC). He leads SPLC’s

Mississippi efforts to reform the state's juvenile justice,

$35.00 for DPCC Member

education, and mental health systems. His practice focuses on

the representation of vulnerable children and to increase

investments in communities and schools. His work has brought

to light horrific and unconstitutional conditions forced upon

children and youth in many for-profit and public juvenile

detention facilities in Mississippi. Previously, he was an attorney

at a nationally-recognized law firm in Jackson, Mississippi,

where he successfully litigated a variety of cases, including civil

rights and constitutional law cases. He also served as a Special

Prosecutor for the District Attorney’s office of Hinds County,

Mississippi, where he prosecuted felony murder cases. He is a

summa cum laude graduate of Jackson State University and

received his law degree from Howard University School of Law

where he was a member of the Social Justice Law Review and the

Huver I. Brown Trial Advocacy Moot Court Team. Mr. Owens is

also a United States Naval Officer. In addition, he serves on

several non-profit boards and most recently was the 2012 Public

Service award recipient for the Magnolia Bar Association and a

2012-2013 fellow for the National Juvenile Justice Network

Leadership Institute. Mr. Owens has been a guest speaker for

several national media panels/outlets on topics such as juvenile

justice, mass incarceration, for profit prisons, and the school to

prison pipeline.

$30.00 for DPCC Student Member

$40.00 for Non-DPCC Member

�Division of

International

Criminology

(DIC)

Invites you to become a

valued member

($20 Existing ASC

member, $15 Students)

www.internationalcriminology.com

Join us for our OPEN DIC Awards Presentation & Reception

Friday November 22nd, 12:30-1:50PM

(Atlanta Marriott Marquis, A602-Atrium Level)

(lunch is available outside the room to bring inside)

There is no charge to attend – all are welcome!

Please help us congratulate our 2013 Award Winners

(Distinguished Book, Outstanding Paper, and Scholar Awards)

And join us for our FREE BOOK RAFFLE of 20 titles!

Benefits of DIC Membership

Inter-News (DIC newsletter) is packed with information about the DIC. Published three

times per year. See past issues at: http://www.internationalcriminology.com/

Free Subscription to the DIC journal: International Journal of Comparative and

Applied Criminal Justice. An excellent outlet for international research.

Listserv to connect and share information with your international colleagues on issues of

research, education, and employment.

Jay Albanese, Chair

jsalbane@vcu.edu

Corinne Davis Rodrigues, Treasurer

crodrigues@ufmg.br

Blythe B. Proulx, Secretary

bbproulx@vcu.edu

�The Criminologist

Page 25

�Page 26

Vol. 38, No. 5, September/October 2013

2013 AMERICAN SOCIETY OF CRIMINOLOGY AWARD RECIPIENTS

ASC FELLOW RECIPEINTS

RICHARD FELSON

Richard Felson is Professor of Criminology and Sociology at Penn State University. Most of his

research is concerned with the social psychology of violence. He has examined, for example, the

role of armed adversaries in explaining race, regional, and national differences in violence. He has

suggested a method that attempts to isolate the causal effects of alcohol intoxication and other situational factors. Recently he has examined age and gender patterns in sexual assault to discern motive. In their book Violence, Aggression, and Coercive Actions he and James Tedeschi developed a

theory of aggression that emphasizes rational choice and social interaction. In his book Violence and

Gender Reexamined he challenged the idea that violence involving women and intimate partners is

much different from other violence. He recently received funding (with Mark Berg) from the National Institute of Justice to study situational factors that produce offender-victim overlap. He has

served on several editorial boards and ASC committees and has given invited lectures at numerous

universities. In 2004 he received the Distinction in the Social Science Award for Research from the

College of Liberal Arts at Penn State.

CHRISTOPHER UGGEN

Christopher Uggen is Distinguished McKnight Professor of Sociology at the University of Minnesota.

He studies criminology, law, and deviance, firm in the belief that good science can light the way to a

more just and peaceful world. He received his Ph.D. from Wisconsin, where he was fortunate to work

with Ross Matsueda. With Jeff Manza, he wrote Locked Out: Felon Disenfranchisement and American

Democracy, and his writing on felon voting, work and crime, and harassment and discrimination is

cited in media such as the New York Times, The Economist, and NPR. He is currently writing a book

comparing reentry from different types of institutions, a series of articles on employment discrimination and criminal records, and several pieces on the health effects of incarceration. Outreach and engagement

projects

include

editing

Contexts

Magazine

(from

2007-2011)

and TheSocietyPages.Org (with Doug Hartmann), a multimedia social science hub drawing approximately one million pageviews per month. He has benefitted greatly from terrific mentors, colleagues,

and students, as well as financial support from NSF, NIJ, NICHD, NIMH, RWJF, JEHT, and OSI. Previous awards include Young Scholar (ISC 1998; ASC 2000); Faculty Mentor (1998, 2011); New York Times Magazine Ideas of

the Year (2003); Outstanding Service (ASA 2011; Department 2009; TRIO 2007), and Equal Justice (CCJ 2011). From 20032009, he served as ASC Executive Secretary.

HERBERT BLOCH AWARD RECIPIENT

MARGARET A. ZAHN

Margaret A. Zahn is a Professor of Sociology at North Carolina State University, and recently served

as a Visiting Professor at the University of South Florida. She has extensive administrative experience, serving as Dean of the College of Humanities and Social Sciences at North Carolina State from

1995-2001, after which she was Director of the Violence and Victimization Division as well as Acting Director of the Research and Evaluation unit of the National Institute of Justice. For a period of

time she also directed the Crime, Violence and Justice Policy Program at RTI International. She has

served in many capacities for ASC beginning in 1973 when she collected fees for the national meetings. Since then she has served, at one time or another, on many of both the elected and appointed

committees. Most recently she was on the Constitution Committee and the Sutherland Award Committee. She was President of the American Society of Criminology in 1998 and was also elected as a

Fellow. Studies of violence, especially homicide, have been her research focus and she has published

numerous articles and three co-edited books on that topic. She recently led the Girls Study Group

project, which was a grant funded multi-disciplinary group oriented toward understanding the causes

of girls’ delinquency and designing gender sensitive programs to combat it. Her edited book,The

Delinquent Girl, was awarded the Choice Award for best scholarship in 2011.

�Page 27

The Criminologist

2013 AMERICAN SOCIETY OF CRIMINOLOGY AWARD RECIPIENTS

OUTSTANDING ARTICLE AWARD RECIPENTS

RONALD L. SIMONS

Ronald L. Simons is a Foundation Professor in the School of Criminology and Criminal Justice at

Arizona State University. After receiving his Ph.D. in sociology at Florida State University, he completed postdoctoral study in the Departments of Psychiatry and Psychology at the University of Wisconsin. He held faculty appointments at Iowa State University and the University of Georgia prior to

joining the faculty at Arizona State University. Much of his research has focused on the manner in

which family processes, peer influences, community factors, and discrimination combine to influence

deviant behavior across the life course. Recently, his work has included a biosocial perspective that

emphasizes the interplay of genes and the social environment and incorporates biomarkers of stress

and health. His work has appeared in journals such as Criminology, Journal of Quantitative Criminology, Justice Quarterly, Journal of Health and Social Behavior, and Developmental Psychology.

Since 1996, he has served as Principal Investigator (along with Drs. Frederick Gibbons and Carolyn

Cutrona) for the Family and Community Health Study (FACHS). Funded by NIMH, NIDA, NCI, and

the CDC, this project has conducted biennial interviews and community assessments with a cohort of

800 African American children who were 10 years of age when the study began and are now in their

late 20s. FACHS is a rich data set that includes interview data from multiple reporters, observational assessments of family and

community processes, GIS information, genotype data, and blood-based assays for biomarkers of stress. Roughly two hundred

papers have been written using FACHS data.

ROBERT PHILIBERT

Dr. Philibert is a faculty member at the University of Iowa in the Department of Psychiatry. He is a

board-certified psychiatrist with 30 years of experience at the laboratory bench top. He has a deep

abiding interest in the epigenetic processes associated with the development of behavioral illnesses. He is also the founder and chief scientific officer of Behavioral Diagnostics, a recently funded

biotechnology company.

STEVEN R. H. BEACH

Steven R. H. Beach received his Ph.D. degree from S.U.N.Y. at Stony Brook in 1985. He joined

the faculty of the Psychology Department at University of Georgia in 1987. He was elected Fellow

of the American Psychological Association (12, 43) in 1994. He currently serves as Distinguished

Research Professor of Psychology and Co-Director of the Center for Family Research at the University of Georgia. Dr. Beach has published more than 250 scholarly papers on marital processes,

family relationships, and their association with depression, substance use, and health. Dr. Beach's

current research interests include examination of the efficacy of marital and parenting interventions, the role of genetic and epigenetic processes in a range of outcomes, and the role of epigenetic

change as a mediator of stress-related health effects. He also has a long-standing interest in the

role of spirituality in marriage.

�Page 28

Vol. 38, No. 5, September/October 2013

2013 AMERICAN SOCIETY OF CRIMINOLOGY AWARD RECIPIENTS

OUTSTANDING ARTICLE AWARD RECIPEINTS (Cont.)

MAN-KIT LEI

Man-Kit Lei is currently a doctoral candidate in the Department of Sociology and a research

statistician for the Center for Family Research at the University of Georgia. He is a past recipient of the Gene Carte Student Paper First-Prize Award from the American Society of Criminology and the Best Graduate Student Paper Award from the Evolution, Biology & Society section of the American Sociological Association. His research interests lie in criminology, methodology, social network analysis, society and health, biosocial studies, community studies, and

family studies. His current research focuses on the ways in which neighborhood factors, family

processes, and genotypes combine to influence well-being across the life course. He also seeks

to develop a new post-hoc test to identify different types of interaction effects. His work has

appeared in American Sociological Review, Violence and Victims, Journal of Family Psychology, and Journal of Marriage and Family.

FREDERICK X. GIBBONS

Rick Gibbons is a Professor of Psychology at the University of Connecticut and a research affiliate in the Center for Health Intervention and Prevention (CHIP). Prior to UConn, he held positions in the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences at

Dartmouth College and the Department of Psychology at Iowa State University, where he was a Distinguished Professor of Liberal Arts and Sciences. His training is in experimental social psychology. However, his primary research interest for the last 20

years has been on the integration of social psychology and health, more specifically, the application of social psychological theories and principles to the study of health behavior. His research uses both experimental laboratory methods and surveys, and he

has also conducted a number of interventions and preventive interventions. A primary focus of this work has been the short and

long-term effects of perceived racial discrimination on the health status and health behavior of African American adolescents and

adults. For the last 15 years, he has been one of the PIs on the Family and Community Health Study (FACHS), which is a panel

study examining the effects of psychosocial factors on the mental and physical health of African Americans.

GENE H. BRODY (Bio and photo unavailable at press time.)

**A complete list of ASC Award winners past and present can be found at http://asc41.com/awards/awardWinners.html **

�Page 29

The Criminologist

ETHICS OF PARTICIPATION AT THE ASC ANNUAL MEETING

The following are standards for participating at the ASC annual meeting, as a session chair, a session presenter, or a poster presenter. They are based on “Guidelines” developed over the years, with updates from the ASC Board. We welcome your suggestions and comments. Please contact Bob Agnew (bagnew@emory.edu) or Becky Block (crblock@rcn.com).

Session Chairs

Arrive at the meeting room a few minutes early and meet briefly with the presenters.

Bring a laptop to the session (or ensure that one of the presenters will bring one that everyone can use). Make sure to allow

time before the session starts to load presentations onto the laptop. You may want to ask that presenters send their slides in

advance so you (or whoever has offered to bring the laptop) can have them pre-loaded.

The session is 80 minutes long. Allow at least 10 minutes for questions and comments from the audience. Divide the time

evenly between the presenters. Inform them of the amount of time available to them at least two weeks before the meeting.

Convene the session promptly at the announced time.

Introduce each presenter with a title and institutional affiliation.

Politely inform the presenters when their time limit is approaching. Many chairs hold up note to the presenter at 5 minute, 1

minute, and the end of their allocated time.

When the announced presentations have been completed, invite questions and comments from the audience. Some chairs

invite speakers from the audience to identify themselves by name and institutional affiliation.

Adjourn the session promptly at the announced time.

If, for some reason, you are unable to attend your session as scheduled, please let each of the presenters and the discussant

know AND designate an alternate chair. Also, call (614-292-9207) or email (asc@asc41.com) the ASC office to tell them

about the change.

Presenters

Screens and LCD projectors will be available in all meeting rooms (except roundtables and posters). Overhead projectors, computers, monitors, the internet, VCRs/DVDs are NOT provided.

If your session includes a discussant, send her/him a copy of the paper at least a month before the meeting.

If you are planning to use slides, send them to the session chair and to the person volunteering to bring their laptop at least

two weeks before the meeting.

Practice your talk ahead of time so that you know it fits within your allotted time.

Your chair will tell you in advance your allotted time. Sessions are scheduled for one hour and twenty minutes (80 minutes).

Divide by the number of people participating in your session, allowing at least ten minutes for questions and answers.

After you pick up your registration materials at the meeting, you may want to spend a few minutes locating the room in

which your session will be held.

Arrive in your scheduled room at least five minutes before the session is scheduled to start.

Plan a brief presentation. The session chair will keep track of time and will alert you when you should begin wrapping up

your talk. Pay attention to these cues. Begin concluding your talk when prompted by the chair.

If, for some reason, you are unable to attend your session as scheduled, please let the chair know. Also, call (614-292-9207)

or email (asc@asc41.com) the ASC office to tell them about the change.

Poster Session Presenters

Poster sessions are intended to present research in a format that is easy to scan and absorb quickly. This session is designed to

facilitate more in-depth discussion of the research than is typically possible in a symposium format. The Poster Session will be

held on the Thursday of the week of the meeting. ASC will not provide AV equipment for this session. There are no electrical

outlets for user-supplied equipment. Push-pins will be provided.

Prepare all poster material ahead of time.

Be sure that your presentation fits on one poster. The poster board is 3 feet high and 5 feet wide.

The success of your poster depends on the ability of viewers to readily understand the material. Therefore:

Keep the presentation simple.

Prepare a visual summary of the research with enough information to stimulate interested viewers (not a written

research paper).

Use bulleted phases rather than narrative text.

(Continued on page 30)

�Page 30

Vol. 38, No. 5, September/October 2013

(Continued from page 29)

Prepare distinct panels on the poster to correspond to the major parts of the presentation. For example, consider

including a panel for each of the following: Introduction, methods, results, conclusions, and references.

Number each panel so that the reader can follow along in the order intended.

Ensure that all poster materials can be read from three feet away. We suggest an Arial font with bold characters.

Titles and headings should be at least 1 inch high. DO NOT use a 12 point font.

Prepare a title board for the top of the poster space indicating the title and author(s). The lettering for this title

should be no less than 1.5 inches high.

Do not mount materials on heavy board. These may be difficult to keep in position on the poster board.

Arrive early to set up. Each poster will be identified with a number. This number corresponds to the number printed in the

program for your presentation.

Make sure that at least one author is in attendance at the poster for the entire duration of the panel session.

Remove materials promptly at the end of the session.

If, for some reason, you are unable to attend your session as scheduled, call (614-292-9207) or email (asc@asc41.com) the

ASC office to tell them about the change.

�ADLER.

FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE.

Offering a 100% online

M.A. in Criminology

The Adler School is founded on an important idea: Our health resides

in our community life and connections. This is what drives our

ground-breaking curricula and commitment to social justice.

Now accepting

applications.

We work with those courageous enough to want to change the world.

866.371.5900

Our master’s and doctoral degrees prepare students with the theory

and practice to become agents of social change. The Adler School —

Leading Social Change. Apply today.

adler.edu

Adler School of Professional Psychology

17 North Dearborn Street, Chicago, IL 60602

�Page 32

Vol. 38, No. 5, September/October 2013

A MORAL PANIC IN PROGRESS: VIDEO GAMES AND THE MEDIA

Chris Ferguson, Stetson University

When society is facing pressing social problems, there is a tendency to seek to place blame on marginalized groups or

cultural elements, including the media. That is the basic premise of Stanley Cohen’s (who sadly died recently) Moral Panic Theory (Cohen, 1972). Moral Panic Theory is fairly well known within criminology, although my own discipline of psychology remains comparatively ignorant of it. Many moral panics focus on juveniles (e.g. juvenile superpredators, an “epidemic” of juvenile female offenders, multitudinous rumors of libidinously innovative juvenile sex parties, etc.). Other moral panics focus on

“low” aspects of culture, particularly the media. Various media, including books ranging from Tropic of Cancer through Harry

Potter, to comic books, jazz, rock and roll, rap, television, movies and video games, have been targets of moral panics.

The tragic shooting in Newtown, Connecticut, in December, 2012, which saw the massacre of twenty children and six

adult school personnel, has created an unfortunate opportunity to watch a moral panic in progress. Speaking as a father myself, I

can understand the psychology of it. Soon after the dreadful shooting, I found myself contemplating the horror that those parents

and loved ones of the victims must be going through. As a nation we mourn for them. But we also want to know why these

events happen, and how we can stop them, however rare they may be, from happening to us. We want to create a sense of being

able to control these uncontrollable events. And so, as a society, we create narratives for how these events happen, focused on

societal elements that “respectable” elements of society disparage. If only we could rid ourselves of these undesirable elements,

we might prevent future occurrences. So the logic goes. That’s the essence of a moral panic. These narratives comfort us, giving

us an illusion of control. The “mad gamer” narrative has been invoked repeatedly when mass shooters happen to be young men

(Ferguson, Coulson & Barnett, 2011).