Goal Setting: A Key to Injury Rehabilitation

Valerie K. Wayda, EdD

Physical Education

Ball State University

,

*--

Francine Armenth-Brothers, MS, ATC

Health Education

Heartland Community College

*-

-

B. Ann Boyce, PhD

Health & Physical Education

University of Virginia

If'

ommitment and motivation are very important to an injured athlete's adherence to

rehabilitation. Athletic therapists

can enhance the athlete's commitment and motivation by making

sure the athlete plays an active role

in the design and implementation

of the rehabilitation program.

If an athlete perceives himself

or herself as an integral part of the

process, he or she is much more

likely to be committed to the program.

One way to make sure an

athlete feels he or she is part of

the process is to have him or her

help set the rehabilitation goals.

Setting goals is not new to athletes. Most are continually driven

to become better at their sport

and thus are naturally goaldirected (Heil, 1993). Their focus

on goal achievement can be

transferred to include the establishment of rehabilitation goals.

Effective goal setting requires

a systematic approach (Boyce &

King, 1993), which few have employed despite the abundance of

articles in support of this strategy.

A systematic approach can enhance the athlete's commitment

and motivation in several ways:

-

clarifies each person's role

gives thc;athlete

Ic both y~~sycholoj

.

. 111s o

yslcally

In

i iitation.

~

Jt

stand the importance oi

Ion exer~

-s optir

1

.

1 .

gives the athlete a feeling

eing back in control.

It holds the athlete accon

given standard

ce.

. .L .. L l,.&,.*..

r

I

,.A

Goal SeBing as a

Psychological Strategy

Goal setting helps the injured athlete by (a) facilitating a faster return (DePalma & DePalma, 1989);

(b) motivating one's effort and

persistence (Weiss & Troxel,

1986); (c) providing a sense of accomplishment (Fisher, Mullins, &

Frye, 1993);and (d) increasing adherence (Fisher, Mullins, & Frye,

1993).

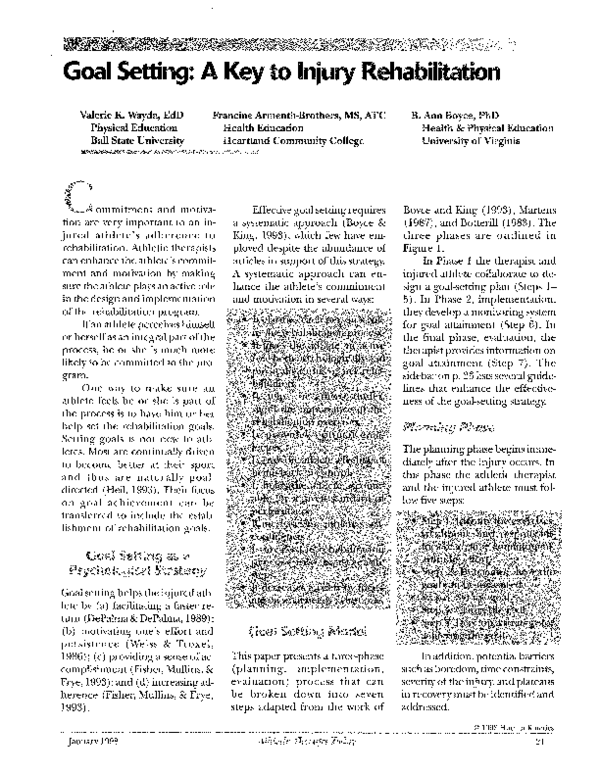

Goal Seeing Model

This paper presents a three-phase

(planning, implementation,

evaluation) process that can

be broken down into seven

steps adapted from the work of

Boyce and King (1993), Martens

(198'7),and Botterill (1983). The

three phases are outlined in

Figure 1.

In Phase 1 the therapist and

injured athlete collaborate to design a goal-setting plan (Steps 15). In Phase 2, implementation,

they develop a monitoring system

for goal attainment (Step 6). In

the final phase, evaluation, the

therapist provides information on

goal attainment (Step '7). The

sidebar on p. 23 lists several guidelines that enhance the effectiveness of the goal-setting strategy.

The planning phase begins immediately after the injury occurs. In

this phase the athletic therapist

and the injured athlete must follow five steps:

.,.

..

. .

,

.

Step 1: Itlentif+the exercises,

treatmc:nt, a n d ~.csponsil)ilities (c'.g., tin~c.cotnnlit~nt:nr,

;irrit~~d(>,

off01.t).

Step 2: Dcterrnine hoiv the

go;11can 1 ) ~ meawrctl.

Stel) 3: Set t l ~ cgoal.

Step 4: (:larif\>t11c goal.

Step 5: I>cvclop;I strategy f i ) ~ ;~chie\ingtlic goal.

In addition, potential barriers

such as boredom, time constraints,

severity of the injury, and plateaus

in recovery must be identified and

addressed.

O 1998 Human Kinetics

January 1998

A & l e ~ cnw~k.&T@d&t~

21

�PLANNING PHASE

9

(Steps 1-5)

?

?

++++

3

+ IMPLEMENTATION PHASE + + + + + + EVALUATION P

(Step 6)

?

C C C C C C C C C C C C C C C C

c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c

Step 1 Identify Exercise, Action,

Responsibility

:meaningful

controllable

focus on individual

Step 6 Monitoring System

record goals

supervise goal process

accountability

reinforcement/support

Step 7 Feedback

reset

new

modify

Step 2 Measurement

objective

specific

criterion for success

Step 3 Set the Goal

difficult but attainable

stated in a positive manner

progressive short-term goals

leading to a long-term goal

Step 4 Goal Clarification

set target dates

prioritize multiple goals

Step 5 StrategyIPlan

achievement strategies

Figure 1 Implementing a goal-setting strategy. (Reproduced w t h permission from the Journal of PhyszcalEducatzon, Remeatton &Dance, J a

Early in Phase 1 the therapist

and the injured athlete discuss the

severity of the injury, the duration

of the disability, the expected recovery level, and the athlete's role

in the rehabilitation process. The

time spent in planning can enhance adherence by clarifying

each person's role in the process.

The following five steps will

explain how the athletic therapist

and the athlete can collaborate

to establish a positive experience.

Step 1: Identification of Exercise,

Action, Responsibilities. One way to

ensure the athlete's active participation in this process is to jointly

iden* the exercise (task),action,

or responsibility (the goal) to be

undertaken. Although the severity

of injury may dictate the type of

goal, an effort should be made to

ensure that the athlete under-

stands why achieving the goal is

critical for successful rehabilitation. The athlete must also perceive the goal as meaningful,

otherwise he or she may not accept it and this could hinder his/

her commitment (Heil, 1993).

Just as one must individualize

the rehabilitation prescription

according to the severity of the

injury, the goal must also be

individualized. Characteristics

such as intrinsic motivation should

be noted when identifying the

rehabilitation goal. Athletes with

low internal motivation may need

more help in identifying and

setting their goals, and more s u p

port as they work to attain those

goals.

In addition, the athletic therapist should ensure that the rehabilitation goal is controllable or

performance oriented as opposed

to an outcome oriented goal. Performance oriented goals are specific behaviors that are directly

under an athlete's control; they

focus on the rehabilitation process. An example is when an

athlete sets a performance goal

of lifting 210 lbs on the leg press

for 10 reps.

Outcome goals are not directly under the athlete's control

and may not be attainable. An injured athlete could set a goal of

regaining his or her starting position on the team, but there is no

guarantee this will happen since

this decision is up to the coach.

Step 2: Measurement. Once the

task, action, or responsibility has

been identified, one must make

sure it is objective and specific. An

objective goal can be measured by

January 1998

�an established instrument and

leaves no question as to whether

the goal has been attained. A

common mistake is establishing

subjective goals, which can be

difficult to determine (e.g., "I want

to throw like I used to").

A specific goal has a criterion

of success and provides clear expectations so the athlete knows

exactly what must be achieved

(e.g., "I need to have 90% strength

as measured by isokinetic testing

on the affected side before full

participation"). Most injured athletes are unaware of what goals

need to be accomplished, therefore the athletic therapist must

guide them to the appropriate

goals.

Step 3: Setting the Goal. Working together, the athletic therapist

can guide the athlete in setting

goals that provide an optimal challenge yet remain physically safe.

Some athletes may set goals that

are either too difficult or too easy.

This may be due to unrealistic

personal expectations, trying to

impress someone, underestimation of ability, being pressured for

a quick recovery, or lack of knowledge. A challenging goal can increase one's level of motivation,

but an unattainable goal can pose

a threat to self-confidence and

physical well-being.

Once a difficult but challenging goal has been determined, it

is important to state it in positive

terms. Have the athlete focus on

what is to be accomplished (success) rather than what to avoid

(failure). For example, instead of

setting a goal of "not being on

crutches for more than 5 days," set

GUIDELINES FOR GOAL SE'ITING

1. Goals should be meaningful to both therapist and athlete.

2. Goals must be performance-not outcome-oriented.

3. Goals should be individualized for each athlete.

4. Goals must be objective and measurable.

5. Goals must be specific.

6. Goals must include a criterion for success.

'7. Goals must be realistic but challenging.

8. Goals should be stated in positive terms.

9. Progressive short-term goals should lead to a long-term goal.

10. Goals should have a target date for completion.

11. Goals should be few and prioritized.

12. Goals should be accompanied by strategies for achievement.

13. Goals must be recorded and monitored.

14. Goals must hold athletes accountable:

15. Goals must be reinforced or supported.

January 1998

AchJe~c~

W ~ T Todagt

PY

ip

d

the goal as "to walk with a normal

gait within 5 days."

In severe injuries, progressive

short-term goals should lead to a

long-term goal. Short-term goals

are important because they tend

to be more flexible than one overall long-term goal. They also provide more frequent feedback,

which can enhance an athlete's

level of confidence and allow

opportunities for constant reinforcement.

Step 4: Goal Clarification.

When determining the goal, it is

important to set a target date for

goal attainment. This will keep the

athlete focused on accomplishing

the goal and provides a medium

in which the therapist can evaluate the progress of rehabilitation.

Depending on the nature or

type of injury, it might be appropriate to set several goals. But

make sure not to set more than

three or four goals and prioritize

them (Boyce & King, 1993). For

example, in most injuries it is important to decrease the pain and

swelling before attempting to

strengthen the injured area. Thus

there is a specific sequence that

could encompass short-term goals

leading to one long-term goal.

Since most athletes have no

medical background, it is imperative the athletic therapist help the

injured athlete sequence these

goals and monitor target dates to

ensure that they are realistic.

Step 5: ~ e u e l e ' an ~

Plan or

Strategy. Once the rehabilitation

goal has been clarified, it is time

to identify strategies that will help

the athlete reach the goal. It is also

important to plan for potential

barriers such as plateaus, boredom, distractions, or alienation.

The following strategies can be

used to prevent these barriers:

�I

avariety of exer

2 , Arrange renanil~rauon

1

1

.

appoinltments around tl

athlete' s practic:e scliedi

,

It is important r-or tne

athlete to remaiin in cor

with thts e a m st~ h e o r s

does not reel* ,~ s c, ,

3. Allow tlle athlet e to express

anger, f rustratic)n,anxie43'7

--- - * L

and 0thL-.C1 ~ I I L U ions.

Reassur.e the at1llete tha

pro,gress will not always

apparel~t and tl lat moqt

lapses a re temporary.

0

.

1

~mg!ementafs'~n

Phase

The implementation phase emphasizes a monitoring system. It

consists of both the athlete and

athletic therapist developing a

regulating system to collect information on progress toward goal

attainment.

Step 6: Monitoring System. A

key component of the monitoring

phase is supervising goal attainment. For example, it could be

helpful to compile a folder for

each athlete that contains the

written goal, documentation of

progress, and other pertinent

information. But make sure the

athlete is involved in this recording procedure since it signifies

his or her responsibility and commitment (Tutko, 1990).

The folder serves many functions, among them, providing a

record of progress for comparing

objective measurements; providing a medium fo'r recording

thoughts and reminders that can

be discussed later; and helping

the athlete feel a sense of ownership by giving him or her a special, confidential plan.

An athlete's motivation and

commitment can also be facilitated through the supervision of

goal attainment. It is important for

the athletic therapist to point out

progress, including small gains,

to the injured athlete since he or

she may not realize that progress

is being made.

Athletic therapists also need

to remind athletes that small setbacks are normal and to focus instead on the overall gains made.

Since most athletes do not understand the healing process, they

need to be educated about normal

progression. If it can be demonstrated to the athlete how progress

is being made, for example ;mall

gains in range of motion, then the

athlete's motivation will likely be

higher.

Second, supervisingan athlete's

progress t@

ward a goal

holds the

athlete ac-

Evaluation Phase

The third and final phase is evaluation. During this phase the athletic therapist provides the athlete

with evaluative feedback in order

for the athlete to assess the goal.

Step 7: Feedback. Once a goal

has been accomplished, there are

two options. The goal could be

reset with a different criterion

(e.g., return to planning phase,

Step 3) or another goal could

be identified (return to planning

phase, Step I).

It is important to remind the

athlete that goal setting is an ongoing, dynamic process, and as

one goal is attained, this is a signal that healing is occurring.

If the goal was not achieved,

review the goal and any problems

encountered (return to the planning or implementation phase) since the

goal may need to be

modified (e.g., tarachievement strat-

setting minimum and maximum

standards and then holding the

athlete accountable for attaining

those standards (Fisher, Scriber,

Matheny, et a]., 1993). In this way

the athlete is more likely to be

committed to the entire rehabilitation process.

Of equal importance to

monitoring and recording goals

are the reinforcement and support of the therapist and others

such as the coaching staff. Words

Stress to the athlete that progress has been made

but that perhaps the goal was not

achieved because of a plateau in

the rehabilitation (Fisher, Scriber,

Matheny, et al., 1993). Discuss

what a rehabilitation plateau is

and modify the target date. Typically athletes will be less frustrated

if they understand that the lack

of progress is simply a temporary

plateau (DePalma & DePalma,

1989).

I

�program. While we recognize that

many individuals do set goals during rehabilitation, the use of a systematic strategy has largely been

neglected. A systematic approach

could enhance the athlete's commitment and motivation since it

ensures that he or she becomes an

active participant at every step of

this strategy.

References

Botterill, C. (1983). Goal setting for athletes

with examples from hockey. In G.L.

Martin & D. Hrycaiko (Eds.), Behavioral

modzjication and coaching Principles, procedures, and research (pp. 67-85). Springfield, IL: C.C Thomas.

Boyce, B.A., & King,

- V. (1993). Goal-setting

strategies for coaches.Journal ofPhysica1

January 1998

Education, Recreation andDance, 63(I), 6568.

DePalma, M.T., & DePalma, B. (1989). The

use of instruction and the behavioral

approach to facilitate injury rehabilitation. Athletic Training, 24,217-219.

Fisher, A.C., & Hoisington, L. (1993). Injured

athletes' attitudes andjudgments toward

l

rehabilitation adherence~ o u r n aofAthletic Training, 28,4854.

Fisher, A.C., Mullins, S.A., & Frye, P.k (1993).

Athletic trainers' attitudes and judgments of injured athletes' rehabilitation

adherence.Journal ofAthletic Training, 28,

4347.

Fisher, A.C., Scriber, K., Matheny, M., Alderman, M., & Bitting, L. (1993). Enhancing athletic injury rehabilitation adherl

Training, 28,312ence.~ o u r n aof~thletic

318.

Heil, J. (1993). Psychology of sport injury.

Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Martens, R. (1987). Coaches guide to sport psycholom. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

-

A

-

Athl&.c 'P7EmaB Today

Tutko, T. (1990, Spring). Character and goals.

The Sports Psychology Newslettm, 5(3), 1-4.

Weiss, M., & Troxel, R. (1986). Psychology of

the injured athlete. Athletic Training, 21,

104109,154.

Valerie K. Wayda is an assistant professor of

sport psychology at Ball State. For the past 3

years her masters level students have collaborated with senior athletic training students on

a psychology-of-injuryrehab practicum experience.

Francine Armenth-Brothers teaches health

education at Heartland Community College

in Bloomington, IL. She holds a masters from

Ball State University.

B. Ann Boyce is associate professor of pedagogy/teacher education at the University of

Virginia. She has conducted research on goal

setting for 10 years and has published research

articles and scholarly papers on this topic.

25

�

Valerie Wayda

Valerie Wayda