Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser.

Case report 415

Related Papers

Skeletal

Radiology

Skeletal Radiol (1987) 16:17(~174

Case report 415

Daryl Fanney, M.D., Jamshid Tehranzadeh, M.D., Robert M. Quencer, M.D.,

and Mehrdad Nadji, M.D.

Departments of Radiology and Pathology, University of Miami School of Medicine, Miami, Florida, U S A

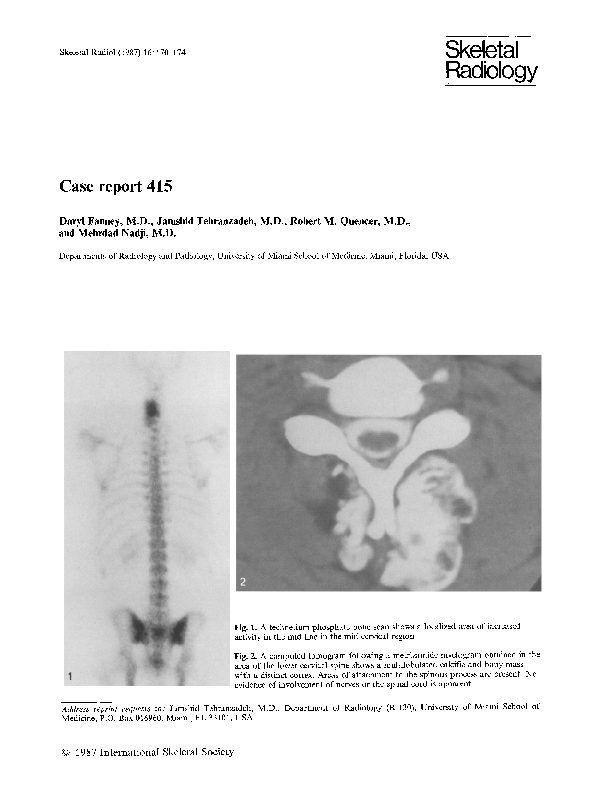

Fig. 1. A technetium phosphate bone scan shows a localized area of increased

activity in the mid line in the mid cervical region

Fig. 2. A computed tomogram following a metrizamide myelogram obtained in the

area of the lower cervical spine shows a multilobulated calcific and bony mass

with a distinct cortex. Areas of attachment to the spinous process are present. No

evidence of involvement of nerves or the spinal cord is apparent

Address reprint requests to." Jamshid Tehranzadeh, M.D., Department of Radiology (R-130), University of Miami School of

Medicine, P.O. Box 016960, Miami, FL 33101, USA

9 1987 International Skeletal Society

D. Fanney et al. : Case report 415

171

Fig. 3. In this magnetic resonance study (mixed TI and T2 M R images, TR : 797 M5, TE : 40MS) sagittal views show an oval

posterior mass with mixed signal intensity present from C3 through C7

Fig. 4. Another M R study (a heavily weighted T2 image T R = 2200 MS and TE:80 MS) in a sagittal view shows the same ovoid

mass with an intense bright signal and lobulation

CHnical information

This 33-year-old man was admitted to the hospital

with a firm, nontender mass in the posterior aspect

of his neck. He first noted the mass two years before admission when he began to experience constant, non-throbbing pain exacerbated by lifting

weights. The patient attributed the mass to muscle

spasm. Six months prior to admission, however,

the patient noticed that the mass was growing and

began to experience paresthesias in the 4th and

5th digits of his right hand. No other complaint

was elicited. His genera/health was good and the

past history was unremarkable.

On physical examination, a protruding, solid,

nontender mass, approximately 7 x 4 cm, was palpated on the posterior portion of the neck with

no evidence of discoloration of the skin or formation of fistula. A plain roentgenogram showed a

large, amorphous, calcific and bony density in the

soft tissues of the neck posteriorly. The technetium

phosphate bone scan showed increased radionuclide activity in the same area (Fig. 1). A myelogram showed no evidence of neural involvement.

Computed tomography, following the myelogram,

showed a large, corticated, lobular density in the

soft tissues of the neck posteriorly, with attachment to the spinous processes of C4, C5 and C6

(Fig. 2). A sagittal view of a magnetic resonance

image at (TR--797 mS and TE: 40 mS) showed

an oval, posterior mass with mixed signal intensity,

extending from C3 to C7 (Fig. 3). A T2-weighted

image (TR = 2200 mS and TE: 80 mS) in the sagittal view showed the same oval mass with a bright,

intense signal with lobulation and septation

(Fig. 4).

An operation was performed.

172

D. Fanney et al. : Case report 415

Diagnosis: Osteochondroma of the cervical spine

The differential diagnosis included chondrosarcoma, myositis ossificans and heterotopic bone formation

of tumoral calcinosis.

The bony mass was resected operatively.

The pathological study showed the tumor to be a 7 x 4.5 x 3.5 cm hard, nodular mass with a focal

attachment of fibroadipose tissue. Microscopically, the lesion was composed of irregular bony trabeculae

and fibrotic bone marrow, covered by a cartilagenous cap of variable thickness ( 1 4 mm) Fig. 5A and

B). An irregular, densely fibrotic epichondrium focally covered the cartilagenous cap. No histological

evidence of malignant transformation was noted.

The final histopathological diagnosis was osteochondroma.

Pathological studies

Fig. 5. A A photomicrograph of the lesional tissue shows a thick, cartilagenous cap covered by fibrous epichondrium. The main

tumor mass is composed of irregular bony trabeculae and a fibrotic bone marrow (HE stain x 35). B Another photomicrograph

in higher magnification (HE stain x 100) obtained from another area of the lesion demonstrates irregular bony trabeculae and

a thin cartilagenous cap

D. F a n n e y et al. : Case r e p o r t 415

Discussion

Benign exostosis (osteochondroma) is a common

bone tumor constituting 9.3% of Dahlin's series.

This tumor may occur in any bone, but usually

develops in the metaphyseal region of long bones,

especially the distal end of the femur. The cervical

spine is an unusual location. In the series of 579

osteochondromas reported by the Mayo Clinic,

only two instances of osteochondroma in the cervical spine were noted [1].

Benign osteochondroma is the most common

benign bone tumor (excepting nonossifying fibroma which also includes fibrous cortical defects),

accounting for 40% of the benign lesions in the

Mayo Clinic series [1]. Since the tumor is usually

asymptomatic, the actual incidence is probably

higher. The lesion enlarges by progressive endochondral ossification of a growing cartilaginous

cap. On plain films, the bony stalk is noted to

project from the surface of a long bone, usually

away from the adjacent joint and the lesion appears smaller than its actual size, since the cartilaginous cap is not well seen. When multiple, the condition is known as hereditary multiple exostoses

(HME). This entity is transmitted as a single autosomal dominant gene. The cartilaginous cap in

any lesion may undergo malignant transformation

to chondrosarcoma. The risk of sarcomatous change in solitary osteochondroma and H M E is less

than 1% and 10% respectively [1].

Although osteochondromas are often asymptomatic, malignant transformation or encroachment

on a nearby joint, vessel, or nerve may necessitate

their surgical removal. Review of the literature reveals that neurological complications of benign exostoses are uncommon and most often occur in

HME. Spinal cord compression is particularly

rare. Madigan et al. [9], reviewed the literature and

documented 13 cases of compression of the cervical

cord secondary to HME. Pain, tenderness, or recent growth of an osteochondroma should alert

the physician to the possibility of malignant transformation. Exostosis bursata (fluid in an adventitial bursa) may mimic this clinical picture and ultrasound has been shown to be helpful in establishing the diagnosis [2]. Most chondrosarcomas arising from exostoses are low grade with subtle malignant features. Consequently, pathological distinction between benign and malignant exostotic chondrosarcoma has been difficult [3]. The surgeon relies heavily on the radiologist not only to differentiate these entities but also to delineate their anatomical relations, since resection will vary accordingly.

Although in most cases this distinction can be

173

made by clinical characteristics and plain radiographs [1, 7], many instances occur when the findings are equivocal. Therefore, other imaging modalities have become increasingly important in the

preopertive evaluation of exostotic cartilaginous

bone tumors.

The role of radionuclide imaging appears limited to screening. Hudson et al. [4], found that intense uptake of 99mTc diphosphonate occurred in

areas of endochondral ossification in benign exostoses, and uptake in chondrosarcoma occurred in

areas of increased osteoblastic activity and hyperemia. Importantly, uptake was not related to

amorphous calcification of cartilage. Consequently, large masses of non-ossifying cartilaginous tissue may not appear on the image at all.

Hudson also reports that, under the age of 29

years, the intensity of uptake was similar in benign

and malignant exostoses. In patients over 30 years

of age, intense uptake supported the clinical diagnosis of chondrosarcoma. However, a normal

study did not exclude malignancy.

Computed tomography (CT), on the other

hand, has proved useful in the preoperative differentiation of chondrosarcoma from benign exostoses. Furthermore, CT helps define the anatomical extent and relations of these lesions. Kenney

et al. [8], developed differential criteria on CT by

depicting internal and peripheral characteristics of

cartilaginous tumors as well as their soft tissue extent. CT images of a benign exostosis demonstrated a bony mass with a sharply defined periphery, a more lucent but organized center with cortex

and medullary cavity continuous with the bone

from which the lesion arose and a thin cartilaginous cap. Criteria suggesting chondrosarcoma included a prominent soft tissue mass with a more

dense heterogeneously calcified center, a thick

(greater than 3 cm) cartilaginous cap and adjacent

bone or soft tissue abnormality. CT also has been

useful in predicting the histological grade of chondrosarcoma. Rosenthal et al. [10], studied 20 cases

of chondrosarcoma and concluded that CT effectively defined several features useful in predicting

histological grade, including (a) morphology of

calcification; (b) distribution of calcification; (c)

pattern of tumor growth and (d) presence of necrosis. They also found that tumor/soft tissue margins

were usually well defined regardless of the grade.

Other authors have been less successful. Hudson et al. [6J, studied 31 CT images of cartilaginous

tumors and showed that CT measurement of the

actual cartilage cap was often imprecise, especially

in the range of 1.5-2.5 cm. They concluded that

CT was not helpful in distinguishing benign exos-

174

toses with thick cartilage caps f r o m c h o n d r o s a r c o mas with relatively thin caps. F u r t h e r m o r e , they

felt that it is often difficult to delineate the outer

surface o f the cartilaginous cap f r o m adjacent normal tissue. H u d s o n et al. [5] r e p o r t e d that a thick

cartilaginous cap o f an exostotic c h o n d r o s a r c o m a

was detected on magnetic resonance ( M R ) b u t not

CT. The m a x i m u m cartilage thickness on p a t h o logical examination o f this r e p o r t e d c h o n d r o s a r c o m a was 1.5 cm. However, a benign exostosis

with a cartilage cap o f 0.2 cm thickness was not

detected by C T or M R I . M R was superior to C T

in delineating b o n e t u m o r s f r o m adjacent muscle

and in showing the relationships to bone o f the

deep margins o f some soft tissue t u m o r s [5]. H y a line cartilage o f articular surfaces shows a bright

signal intensity on magnetic resonance imaging. Fibrocartilage, in contrast, has a low signal intensity

and appears as a d a r k or dark-grey structure. The

cartilage cap a r o u n d an o s t e o c h o n d r o m a is composed o f hyaline cartilage which should have a

bright or light grey signal. In this o s t e o c h o n d r o m a

o f the neck, the cartilaginous cap was thin and

the variable thickness o f the cap (1-4 mm) was

not detected by M R . The main bulk o f osteochond r o m a on M R is n o t e d as a mass o f mixed d a r k

and bright signals. The d a r k - a p p e a r i n g areas represent ossified cartilage or b o n y trabeculae interspersed by the bright signals o f fibrous connective

tissues (Figs, 3 and 4).

In summary, a large mass in the neck o f a

33-year-old m a n radiologically and histologically

c o n t a i n e d b o n y and cartilaginous elements and involved the posterior elements o f several cervical

D. Fanney et al.: Case report 415

vertebrae. T h e lesion p r o v e d to be a benign osteoc h o n d r o m a in an unusual location, m a k i n g its distinction f r o m c h o n d r o s a r c o m a and several other

entities difficult by plain films alone. The differential diagnosis was offered and the diagnostic radiological features o f o s t e o c h o n d r o m a were described.

The relative values o n scintigraphy, c o m p u t e d tom o g r a p h y and magnetic resonance imaging in the

evaluation o f cartilaginous t u m o r s were discussed.

References

1. Dahlin DC (1978) Bone tumors. General aspects and data

on 6,221 cases. 3rd ed. Charles C Thomas, Springfield, p 18

2. E1-Khoury Gay (1979) Symptomatic bursa formation with

osteochondromas. AJR 133:895

3. Henderson ED, Dahlin BC (1963) Chondrosarcoma of

bone: a study of 288 cases. J Bone Joint Surg 45 A: 1450

4. Hudson TM, Chew FS, Manaster BJ (1983) Scintigraphy

of benign exotoses and exostotic chondrosarcomas. AJR

140:581

5. Hudson TM, Hamlin DJ, Enneking WF, Pettersson H

(1985) Magnetic resonance imaging of bone and soft tissue

tumors. Skeletal Radiol 13:134-136

6. Hudson TM, Springfield DS, Spanier SS (1984) Benign exostosis and exostotic chondrosarcoma: evaluation cartilage

thickness by CT radiology. 152:595

7. Huvos AG (1979) Bone tumors: diagnosis, treatment and

prognosis. WB Saunders, Philadelphia, pp 139-152;

206-237

8. Kenney PJ, Gilila LA, Murphy WA (1981) The use of computerized tomography to distinguish osteochondroma and

chondrosarcoma. Body CT 139:129

9. Madigan R, Worral T, McClain EJ (1974) Cervical and

compression in hereditary multiple exostoses. J Bone Joint

Surg 56-A:401

10. Rosenthal DI, Schiller AC, Manken HJ (1984) Chondrosarcoma: correlation of radiologic and histologie grade. Radiology 150:21

RELATED PAPERS

Nanobiotechnology Reports

X-ray Fluorescence Analysis of the Composition of the Alloy of Rare Figural Weights of the 5th Century with an Image of the Emperor on the Throne2023 •

Ágora Filosófica

Modality, propositional functions, and logical learning.2023 •

Magazin. Revista de Germanística Intercultural

Stork, Regina. (1999). Deutsch als Fremdsprache im Bereich TourismusPedagogía Social. Revista Interuniversitaria

Editorial: La pedagogía social en tiempos difíciles (2020)2020 •

Scenario: A Journal of Performative Teaching, Learning, Research

Drama: Threat or Opportunity? Managing the ‘Dual Affect’ in Process Drama2014 •

International Journal for Numerical Methods in Biomedical Engineering

Patient-specific fracture risk assessment of vertebrae: A multiscale approach coupling X-ray physics and continuum micromechanics2016 •

2023 •

Catering Nasi Kotak Komplit Trucuk Kalitidu Bojonegoro

MURAH - WA : 0813-3339-2171 (TSEL), Catering Nasi Kotak Komplit Trucuk Kalitidu Bojonegoro2012 •

Journal of Proteomics

Proteomic analysis of A2780/S ovarian cancer cell response to the cytotoxic organogold(III) compound Aubipyc2014 •

Revista Brasileira de Terapias e Saúde

Análise histológica dos efeitos da radiofrequência na pele2020 •

RELATED TOPICS

- Find new research papers in:

- Physics

- Chemistry

- Biology

- Health Sciences

- Ecology

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

Robert Quencer

Robert Quencer