Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser.

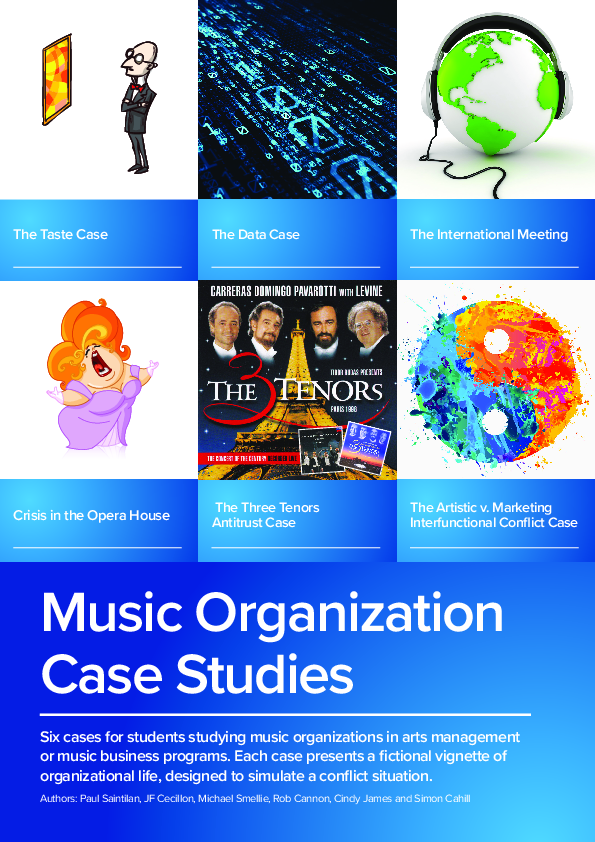

Music Organization Case Studies

Music Organization Case Studies

Six cases for students studying music organizations in arts management or music business programs. Each case presents a fictional vignette of organizational life, designed to simulate a conflict situation.

The Taste Case

The Data Case

The International Meeting

Crisis in the Opera House

The Three Tenors

Antitrust Case

The Artistic v. Marketing

Interfunctional Conflict Case

Music Organization

Case Studies

Six cases for students studying music organizations in arts management

or music business programs. Each case presents a fictional vignette of

organizational life, designed to simulate a conflict situation.

Authors: Paul Saintilan, JF Cecillon, Michael Smellie, Rob Cannon, Cindy James and Simon Cahill

Case study 1: Crisis in the

Opera House

Case study 5: The

International Meeting

An artist relations case study © 2013, 2023

Paul Saintilan

© 2013, 2023 Paul Saintilan, Michael Smellie &

Cindy James

This case explores issues such as the management

of creative processes, artist relations, prima donna

behaviour, organizational culture and values, and

artistic leadership.

This case explores issues such as the organizational

tension that occurs between centralization and

decentralization, and tensions that arise between

head offices and branches.

Case study 2: The ‘Taste’ Case

Case study 6: The Three Tenors

Antitrust Case

Should artistic leaders drive decision making from

their own taste?

© 2013, 2023 Paul Saintilan & Rob Cannon

This case explores issues such as artistic decision

making, tastemaking, artistic programming, personal

taste and artistic leadership.

Case study 3: Did You Find the

Voice of God in the Data?

How useful is customer data for music NPD?

© 2013, 2023 Paul Saintilan & JF Cecillon

This case explores topics such as new product

development, market research, data analytics, social

media, ecommerce data and audience feedback.

Case study 4: The Artistic v.

Marketing Interfunctional

Conflict Case

© 2013, 2023 Paul Saintilan & Simon Cahill

This case explores interfunctional conflict at

the artistic/marketing interface in large music

organizations.

© 2013 Paul Saintilan

This case explores issues such as antitrust /

anti-competitive behaviour and the structuring

of joint venture projects. Instead of being a

fictional vignette, or conflict scenario, designed to

encourage discussion, it presents an analysis of

an historical case.

These cases can be used free of charge for

educational use, without the permission of the

authors. They can be freely distributed in soft or

hard copy, or placed on digital blackboards and

online teaching platforms with no license fee

payable. They can be reproduced or excerpted in

other publications without payment or additional

permission as long as the relevant authors are

credited and any changes to the original text are

transparently acknowledged.

Crisis in the Opera House

A case study for students studying music organizations in music business

or entertainment management programs.

The tempestuous operatic soprano Valerie Vesuvius erupts, nearly killing an intern and a member of

the artistic administration team, and engulfing the national opera company in crisis. The CEO convenes

a meeting in the boardroom for senior management to discuss the situation. Senior executives adopt

conflicting positions, encouraging class debate on the appropriate course of action.

Keywords: artist relations, managing creativity, prima donna, opera, organizational culture and values,

leadership

Author: Paul Saintilan

Crisis in the Opera House

© 2013, 2023 Paul Saintilan

About the Author

Dr Paul Saintilan is a creative industries ‘pracademic’,

author, teacher and industry consultant. He has

worked in international roles at EMI Music and

Universal Music in London as well as non-profit roles in

classical music organizations.

This case can be used free of charge for educational

use, without the permission of the author. It can be

freely distributed in soft or hard copy, or placed on

digital blackboards and online teaching platforms with

no license fee payable. Feedback would be appreciated

on the case (via paulsaintilan@gmail.com). Readers who

provide suggestions which are incorporated will receive

acknowledgement in future editions of the case.

All characters in this work are fictitious. Any

resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is entirely

coincidental.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Moffatt Oxenbould AM,

former Artistic Director of Opera Australia, for extremely

helpful suggestions which undoubtedly improved the

case. Dr Guy Morrow also provided generous advice on

resources and angles.

Designed by Ersen Sen. Images licensed through

Shutterstock. Interior opera house image Natia Dat /

Shutterstock.com

Second edition. First edition published by The

Australian College of the Arts (‘Collarts’) in 2013.

Crisis in the Opera House: © 2013, 2023 Paul Saintilan

2

Valerie Vesuvius had an international reputation for

being ‘difficult’ and her backstage tantrums were

legendary within the House. Up to this point, the

company had tried to ‘manage’ the issue, retaining a

relationship with its publicly adored and ‘bankable’

star, while trying to appease disgruntled cast

members and staff.

On this occasion the diva had flown in late for

rehearsals, and by the end of her first day in

the building had missed a number of crucial

appointments and insulted most of the people

working in the makeup and costume departments.

She was supposed to be performing the role of Mimi

in Puccini’s La Bohème, which was due to open in

only three days’ time.

The CEO, Imogen Impresario, had convened a

meeting in the boardroom for senior management

to discuss the situation. Impresario looked around

the table. She had joined the company only one

month earlier, and found herself ascending a steep

learning curve. Prior to this position she had been

CEO of a private foundation which disbursed grants

to arts organizations.

Marc Monet, the artistic director, was the last to

arrive. He glided into the room, immaculately

dressed, apparently unruffled by the morning’s

tumult. The CEO turned towards him. ‘OK, Marc,

perhaps you could start by talking us through your

understanding of exactly what happened.’

‘Certainly. I think we all know the long, tortured

history of this saga, but in terms of what triggered

the last convulsion ... the sequence of events

appears to be that yesterday Vesuvius finally

turned up around 10am, two days late, and thus in

breach of her contract. She attended one music

call, momentarily, but then insulted the production’s

Musetta and left. She fleetingly attended a fitting but

insulted the wig master and left. She didn’t attend a

press call that had been scheduled for her. Instead,

she roamed the building, creating a firestorm of ill

will in a number of departments. Both our Musetta

and the wig master were later seen leaving the

building in tears. This morning Michelle from artistic

Crisis in the Opera House: © 2013, 2023 Paul Saintilan

administration went to see Vesuvius, and privately

questioned her professionalism. This triggered a

second explosion, where the artist threw a bust

of Puccini at her, narrowly missing an intern, but

taking out an empty vase. Michelle claims she was

hit by shrapnel from the vase, which drew blood.

Vesuvius then marched into my office, demanding

Michelle’s dismissal. I declined her request. She

then stood in my doorway spewing molten lava,

before storming out of the House, leaving a trail

of sulphurous gases. To my knowledge she is

currently uncontactable. We have a full dress

rehearsal commencing in four hours.’

‘Thanks very much, Marc,’ said Impresario. ‘What

on earth was Michelle doing taking an intern on a

mission like that?’

‘The meeting was scheduled to take place anyway

on quite a different matter – Vesuvius sends them

scurrying all over the place on personal errands – but

apparently Michelle felt that she had no alternative

but to be drawn into a discussion about it.’

‘Given yesterday’s events, of which she would have

undoubtedly been aware, it showed a distinct lack of

judgement,’ Impresario responded drily.

‘Is it a mistake to feel that one is entitled to work in

an environment without bullying and intimidation?

Michelle is a superb member of our team and was

doing what she felt to be in the best interests of the

company and her colleagues.’

‘She had every right to bring this to our attention.

But she made a mistake in taking everything upon

herself. While we would all agree that there is

conduct that is unprofessional and unacceptable,

before starting down a path that can lead to

explosions, we first need to fully understand

the implications of that step, which is a complex

calculus. She is not in the best position to make

that calculation. And secondly, we also need to

determine the most effective way of dealing with the

situation. Someone at her level has fewer options

than we have as a team, which is why difficult artist

relations issues need to be brought to my attention,

3

or your attention. We might feel it is sufficient to have

a quiet word with the manager or agent, and let them

deal with it. We might design a scenario whereby

a staff member the artist trusts brings it up at an

appropriate moment. We might call a formal meeting

with the artist and the manager, and invite a number

of staff along to lend it more gravity. We might issue

her with a formal written warning. We might advise

that we refuse to offer her any future engagements

beyond those already contracted. We might terminate

her agreement due to unprofessional conduct. There

are a range of options.’

Monet played ostentatiously with his cufflinks.

‘Refusing to offer any future engagements might

provoke Vesuvius to withdraw, in which case the

audience would see her withdrawal as her fault

and not ours. It would also send a clear signal

to the company as a whole that her behaviour is

unacceptable … It’s worth us considering …’

The CEO nodded. ‘Before we leave the subject of

Michelle, I also believe she got emotional, raised her

voice and became abusive to Vesuvius.’

‘That’s true. It was highly regrettable, but she was

provoked.’

‘She shouldn’t sink to the same level as the

person we’re condemning. I respect you standing

up for members of your team, but I expect more

professionalism. In this business you need a thick

skin. We all know that.’

Colin Cash, the financial controller, chimed in. ‘I

would just like to add in terms of the “complex

calculus” that we have her performing in the tour

we’re running through a number of Asian cities next

year. We’re pretty handsomely subsidized for that

tour, and so it contributes financially to our year

end targets. She has an enormous following out

there, and the tour is somewhat built around her

involvement. If she pulls out or feigns illness it may

jeopardize the tour.’

Monet adjusted his cravat. ‘I don’t see why this is

such a big deal. We’ve had artist blow-ups before,

and we just deal with them. That is what we do. That

is what I do. This is an artistic decision.’

‘Certainly, but it’s also a corporate decision,’

responded the CEO. ‘There’s too much at stake in

terms of revenue, risk, reputation … It impacts on too

many other things.’

‘Everywhere I’ve worked we’ve always had

Vesuviuses,’ Monet continued. ‘Perhaps not as

Crisis in the Opera House: © 2013, 2023 Paul Saintilan

damaging, but there’s always been one. Do we

want to work with creative people? Great artists

aren’t normal. Great artists are extreme, and

extreme people do extreme, mad, crazy things. This

is what working in the arts is all about. If you want

to work with boring, normal people, go and work

in a bank, or for a toothpaste company. Vesuvius

is a perfectionist – she’s no harder on the people

around her than she is on herself. We need to

work with people like her or we shouldn’t be in this

business. It is just a case of me going back to her

with a stronger line. And I am perfectly capable of

doing that.’

The head of marketing, Betty Blacktown, spoke up.

‘Opera is about big personalities. And the media

and public love drama; it makes artists interesting.

Otherwise she would be some boring, vanilla

singer. She’s a prima donna, which is a good thing.’

The human resources director, Sharon Shield,

was the next to wade in. ‘Well, as I understand it,

“prima donna” simply means “first lady”, or the

best person for a role – it doesn’t give someone a

licence to abuse, intimidate and humiliate staff. This

is workplace bullying. Pure and simple. It opens up

the company to legal risks. If we ignore or excuse

this sort of behaviour, we send a clear message to

staff that we consider bullying to be acceptable. We

send a clear message to the other, admittedly few,

difficult artists that they can get away with virtually

anything while they’re here. It can result in stress

leave, allegations of harassment, a hostile work

environment and discrimination. Vesuvius is sick,

she’s an organizational sociopath or psychopath.

She needs help.’

Monet continued the pro-artist line. ‘I think we

need to recognize that stars are often insecure,

vulnerable and under enormous pressure. They

spend half their lives jetlagged, hearing about

catty reviews or reading negative social media

comments. Most artists don’t actually understand

the connection they have with an audience and

live in perpetual fear that one night the magic just

won’t happen. There is also “creative conflict” in

rehearsal situations, which is normal. Sometimes

sparks of genius fly off in creative confrontations.’

‘The conflict here has nothing to do with the

creative process,’ Shield replied. ‘She wasn’t

remotely near a rehearsal room. My view, for what

it’s worth, is that she’s a predatory, narcissistic

bitch, and if we don’t put our foot down, we’ll just

refuel her belief that she is entitled to get away

with it.’

4

Impresario turned again to Monet. ‘Is there any way

we can keep her more isolated and stop her from

poisoning everyone?’

Monet retorted, ‘May I remind people that

‘excellence’ is also a value, and that despite her

undoubted flaws, she is capable of delivering artistic

excellence at an unparalleled level.’

Monet shook his head. ‘I don’t see how in a

collaborative art form like opera you can quarantine

someone. Particularly the star of the show.

Collaborative and collegial attitudes are necessary

for the whole ensemble to flourish.’

‘Yes,’ Shield responded, ‘but if she compromises the

work of others, and opera is a collaborative art form,

as you say, then the total excellence diminishes.’

‘In terms of fallout, what’s the conductor saying?’

continued Impresario.

Impresario reasserted her authority on the meeting

with renewed vigour. ‘OK. There are a couple of

practical points I need to go over with you, Marc.

What does her contract say?’

Monet smiled, and attempted his thickest Eastern

European accent: ‘She is bitch. Big, crazy bitch. She

no good for health, like Chernobyl. But very good

singer, like Callas. Callas also bitch. They make big,

angry experiences. Vot to do?’

‘I believe that there is a pro forma clause around

conduct that would serve as adequate grounds for

termination.’

‘And the director?’

‘And if we were to sit her down and strongly

intervene, what would be her reaction?’

‘The same.’

‘I don’t think she would respond constructively.’

‘I know I’m the boring finance guy’ interjected Cash,

‘but what we need to do at some point is a quick

“back of the envelope” cost-benefit analysis. If we

can’t afford to lose her, dealing with the aggravation

may just be a cost of doing business. We need to

explore the financial and practical implications of

replacing her. We need to define the parameters

in which we can work and know the long term

cost before we do anything drastic. What are we

actually deciding here? And who is deciding? Is

this something that should be decided by the

management team, or left to the CEO and artistic

director after we have all been consulted?’

‘And what about her cover? How well covered are

we?’

There was a pause. The CEO looked uncertain.

Shield continued. ‘It goes deeper than a cost-benefit

analysis. It comes down to culture and values. What

sort of company are we? What do we actually stand

for? What do we expect of ourselves and others?

Let’s look at our mission statement. From memory it

says something like “we are committed to our values

of cooperative teamwork and mutual respect”. I

have heard it said in these corridors that “our job

is to provide an environment in which an artist can

give of his or her best”. Can we honestly say that

the environment at the moment is conducive for the

other artists in this production to “give of their best”?

Of course not. The bottom line is that Vesuvius has

no respect for her colleagues. What price do we put

on values like respect and integrity? Sure, do your

cost-benefit analysis, but at some point you will be

trying to price the priceless.’

Crisis in the Opera House: © 2013, 2023 Paul Saintilan

‘Artistically, very strongly. But of course the cover has

a much lower profile from an audience perspective.’

Betty Blacktown jumped in. ‘Vesuvius is a big draw,

but Bohème is Bohème. I think I could sing Mimi and

we’d still get an audience.’

‘If we do dismiss her,’ said Impresario, ‘what sort of

language should we use in the announcement?’

Monet paused. ‘Well, the normal language is that

the artist is “indisposed”, whatever that means, or

has some cold or flu. But I don’t think that would

work in this case. I think tensions have filtered out

sufficiently for a few critics and bloggers to know …

In which case the clichéd line is that we are parting

company on this production due to “irreconcilable

creative differences”.’

‘Is there any other additional leverage we have over

her? Is there anything else that we are supporting

that we could look to withdraw?’

‘Nothing out of the usual. I’ll check.’

‘OK. To wrap up here, Marc, I would be grateful if

your Department could construct a highly detailed

timeline of recent events, with an accuracy down

to the minute, and against each event list the

people who witnessed it. Please bring me the

bust of Puccini and the broken vase. Also, please

5

check the relevant clauses in the contract plus any

other favours we may be doing for her. Finally, at

least attempt to track down the diva for the dress

rehearsal this afternoon and check on the readiness

of the cover. Betty, we need our publicist on standby

in case we need to draft a media release. Colin,

please work up a draft cost-benefit analysis we can

discuss after lunch. Let’s meet back here at 2pm

sharp. Marc, would you stay behind? Thank you.’

The meeting broke up. Impresario pondered the

dilemma. If they did act, how strongly should they

intervene? A gift for handling temperamental artists

is seen as an asset in this business. If she is seen

to terminate the agreement, would she look like a

naïve newcomer who doesn’t understand opera

and handling superstar artists? Would a failure to act

undermine her authority with the whole company?

Would refusing to delegate the decision to Monet

alienate the two of them? Could she be complicit in

supporting a toxic culture of bullying?

Discussion questions:

1. Compare and contrast the conflicting positions

around the table.

This case appears in the textbook Managing

Organizations in the Creative Economy:

Organizational Behaviour for the Cultural Sector

by Paul Saintilan and David Schreiber. The first

edition was published by Routledge in 2018, and

the second edition is scheduled for 2023. The

textbook examines topics relevant to this case such

as managing creativity, personality and creativity,

artistic leadership, decision making in creative

organizations and organizational culture and values.

2. To what extent should the audience’s ‘rights’ and

expectations be considered?

3. Undertake a cost-benefit analysis of dismissing

Vesuvius.

4. What should Impresario do, both in terms of the

key decision and the way she communicates it?

5. What other policies, practices and processes

should she review?

6. In so far as there is positive ‘creative conflict’ in

the case, where does it take place?

7. What values should an opera company have,

and how should they be prioritized?

Crisis in the Opera House: © 2013, 2023 Paul Saintilan

6

The Taste Case

A case study for students studying music organizations in music business

or entertainment management programs.

Should the artistic leader of a music organization select artists and repertoire based on their own personal

taste? Is it natural and inevitable or an unprofessional indulgence? A group of artistic directors and A&R

heads argue over lunch ...

Keywords: taste, artistic leadership, ‘tastemaker’, A&R, artistic programming

Authors: Paul Saintilan & Rob Cannon

The Taste Case

© 2013, 2023 Paul Saintilan & Rob Cannon

About the Authors

Dr Paul Saintilan is a creative industries ‘pracademic’,

author, teacher and industry consultant. He has

worked in international roles at EMI Music and

Universal Music in London as well as non-profit roles

in classical music organizations.

Rob Cannon is a coach, consultant and educator

specializing in the arts and entertainment industry.

He is an academic lecturer at the Australian Institute

of Music, and has previously held international

record company roles.

This case can be used free of charge for educational

use, without the permission of the authors. It can be

freely distributed in soft or hard copy, or placed on

digital blackboards and online teaching platforms

with no license fee payable. Feedback would be

appreciated on the case (via paulsaintilan@gmail.

com). Readers who provide suggestions which are

incorporated will receive acknowledgement in future

editions of the case.

All characters in this work are fictitious. Any

resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is

entirely coincidental.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Shae Constantine

and Jeremy Youett for ideas that strengthened

the case.

Designed by Ersen Sen. Images licensed through

Shutterstock. Sydney Harbour image Ingus Kruklitis /

Shutterstock.com.

Second edition. First edition published by The

Australian College of the Arts (‘Collarts’) in 2013.

The Taste Case: © 2013, 2023 Paul Saintilan & Rob Cannon

2

Blake and Jade arrived at the restaurant slightly

ahead of the others and took their seats at a table

overlooking Sydney Harbour. It was a beautiful

day, and a ferry glided through the sparkling water,

making its way out of the Quay towards Manly.

Blake was the artistic director of a large international

orchestra and Jade the artistic director of a music

festival. Within minutes they were joined by Cindy

and Chris, who both worked as A&R heads for major

record companies. All four had spent the morning as

guests at a government funded seminar on ‘business

creativity’.

They ordered their meals and spent some time

discussing the difference between artistic and

managerial creativity, a topic that had surfaced

during the seminar. But then the conversation

lost momentum. As an aside, Blake commented:

‘I thought it was really interesting what Ariel was

saying at the coffee break about the relationship

between “taste” and one’s own professional

judgement in selecting artists, repertoire and

projects. I’ve been reflecting on what my own views

are. I think I do drive my orchestral programming

decisions out of personal taste. I don’t see how

you can do otherwise. Your personal response

to music, your passions, your enthusiasms, your

musical addictions, how can you clinically disengage

them from your professional judgement? And if I

personally respond to something, it convinces me

that it’s an authentic choice, and if I like it others

might like it, and then I can fight for it, and hope it

connects with others in the same way it connects

with me.’

Cindy reached across the table and grabbed a bread

roll. ‘Yeah, I’d like to be able to do that. But I don’t

have the luxury of my personal tastes in music. If I

was running my own small indie label, then maybe

I could, but we’re a big company that needs to

cater for a really diverse range of tastes. We’re not

creating music for ourselves, we’re creating music

for a whole spectrum of artists and audiences. So it

needs to be a lot broader than just my taste.’

‘Sure. But I think to some extent an artistic leader

needs to stand for something and take a leadership

The Taste Case: © 2013, 2023 Paul Saintilan & Rob Cannon

position. Or why have them? You need to play to

your strengths, not pretend that you know about

a million genres when you don’t. You know? If you

want someone who knows their way around K-Pop

or electronica, don’t come to me. My musical tastes

define me, it’s part of who I am. As artistic leaders

we need our own signature, our own imprimatur, our

own brand. To some degree I was hired for my taste,

I’m a ‘tastemaker’, so surely it’s legitimate for me to

exercise it?’

‘That sounds great, don’t get me wrong,’ countered

Cindy, ‘but in my situation, it’s really important that I

don’t have any emotional skin in the game. ‘Cause

sometimes you need to pull the plug on projects,

and that’s hard to do if you’re too passionate, or

personally committed.’

‘Sure. But don’t you find that projects are always

emotional? They’re always an emotional brawl! I

need to fight for my vision on a daily basis. You know

there are always doubts and fears and uncertainties

in music organizations, and it’s our job to sell new

projects and sell them hard. I think an audience can

sense passion, and belief and conviction, and the

more passionate I am, the more passionate I believe

the audience will eventually be. I think we actually

impose our taste on others down the line, and in your

business people like Clive Davis have been doing

that for years.’

Cindy smiled. ‘My job is to make profit. Pure and

simple. We’re a publicly listed company. We need

a return on investment. So I need to take myself

out of the equation and maybe do things that other

people will like, even if I don’t. In fact, I need to

work on projects that I personally loathe and detest

if it connects with some audience we can make

a buck out of. And if you can’t do that, you’re not

a professional. You know, that’s actually been the

problem with some A&R guys, that they’re wanting

to be so cool and credible and edgy, that they hate

the mainstream bands that actually pay their salary or

refuse to sign them in the first place. You also need to

understand that the era of ‘gut feel’ has largely ended

in commercial music. Our decision making is more

and more driven by social metrics and consumer data.

3

‘Well ... ,’ concluded Blake, shaking his head, ‘I bet

that nine times out of ten when an A&R person signs

a band, it’s because they like them. And they will

selectively choose the data to support their position.

Seriously. What do you other two think?’

Discussion questions:

1. Which of the artistic leaders do you agree with

and why?

2. Who do you disagree with and why?

Chris put down a glass of wine. ‘It’s an interesting

discussion. I think artistic leaders should be really

transparent and upfront about acknowledging their

tastes. I might think that my taste is really broad

and Catholic, but it probably isn’t. Have you ever

had the experience where you ask someone what

they like, and they say “everything”, but when you

get down to it, and offer them tickets and stuff, it

becomes apparent that there’s a ton of things that

they actually hate, things that other people might

love. If I declare that I hate salsa or reggae or jazz,

then the organization can put decisions relating to

those genres out to other people, so it’s worth the

organization knowing. Otherwise I may be making

decisions that aren’t in the best interests of the

business, simply because I don’t have any empathy

with a certain type of music.’

3. Explore how the organizational context in which

each executive works has influenced their

views. For example, should not-for-profit entities

like orchestras differ in how they make artistic

decisions over ‘for-profit’ firms like commercial

record companies?

This topic is further explored in the article ‘Aesthetic

preferences and aesthetic ‘agnosticism’ among

managers in music organisations: is liking projects

important?’ by Paul Saintilan, published in the

International Journal of Music Business Research,

October 2016, vol. 5 no. 2, pp. 6-25. Available at

https://musicbusinessresearch.files.wordpress.

com/2016/10/volume-5-no-2-october-2016-saintilan.pdf

‘I agree with that,’ responded Blake. ‘I believe an

artistic director needs to stand for something and be

hired or fired on that basis. So I agree with you that

honesty and accountability are important. If I hate

hip hop, and the organization needs hip hop, then

fire me and give the gig to someone who loves hip

hop. What about you, Jade?’

‘I believe that I have internalized the audience into

my own personal responses. I think I have spent so

much time seeing what my audience reacts to, what

they love, what they hate, that when I look at new

ideas it is impossible for me not to compute that into

my thinking, even subconsciously.’

‘Interesting ... What about people who don’t attend

often – who aren’t part of your current audience. Are

you choosing for them too?’

A waiter interrupted the conversation, carrying out

the first of the meals. They turned their attention

back to the sparkling Harbour.

The Taste Case: © 2013, 2023 Paul Saintilan & Rob Cannon

This case appears in the textbook Managing

Organizations in the Creative Economy:

Organizational Behaviour for the Cultural Sector

by Paul Saintilan and David Schreiber. The first

edition was published by Routledge in 2018, and the

second edition is scheduled for 2023. The textbook

examines topics such as decision making in creative

organizations, tastemaking and artistic leadership.

4

‘The Data Case’:

Did You Find the Voice

of God in the Data?

A case study for students studying music organizations in music business

or entertainment management programs.

Sheldon Cybertron, the newly appointed VP of Data Analytics at Galaxy Records, was on fire. He had

already earned the respect of his colleagues for his valuable marketing insights. Yet he wanted more. He

wanted to help guide the new creative work of the label’s biggest stars. But the CEO was dismissive of his

ideas. ‘You know, Sheldon, every time the Romans were saying “Vox populi, vox Dei”, “the voice of the people

is the voice of God”, that was when they didn’t know what to do!’

Keywords: new product development, market research, data analytics, social media, ecommerce data and

audience feedback.

Authors: Paul Saintilan & JF Cecillon

Did You Find the Voice of God in the Data?

How useful is customer data for music NPD?

© 2013, 2023 Paul Saintilan & JF Cecillon

About the Authors

Dr Paul Saintilan is a creative industries ‘pracademic’,

author, teacher and industry consultant. He has

worked as an international marketing director at EMI

Music and Universal Music in London, as well as in

non-profit roles in classical music organizations.

JF Cecillon is the former Chairman and CEO of EMI

Music International.

This case can be used free of charge for educational

use, without the permission of the authors. It can be

freely distributed in soft or hard copy, or placed on

digital blackboards and online teaching platforms with

no license fee payable.

All characters in this work are fictitious. Any

resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is entirely

coincidental.

Acknowledgements

Designed by Ersen Sen. Images licensed through

Shutterstock. Cover image by spainter_vfx. Internal

image by Andrey Po.

Second edition. First edition published by The

Australian College of the Arts (‘Collarts’) in 2013.

‘The Data Case’: Did You Find the Voice of God in the Data?: © 2013, 2023 Paul Saintilan & JF Cecillon

2

Sheldon Cybertron had recently been appointed

Vice President of Data Analytics and Customer

Insight at Galaxy Records. From deep within his

social and digital media Command & Control Centre,

a nuclear bunker in the building’s basement, his

department crunched through enormous volumes

of customer data. The sources of data had exploded

in recent years, from social media, to e-commerce,

streaming and licensing platforms, to new Web3

data coming from NFT sales and the label’s

involvement in ‘play to earn’ video games. His

work also extended to building the label’s market

research capability, proactively testing customer

needs, tastes and preferences.

at our broader artist and repertoire portfolio, and

assess the balance of what we have versus what we

should have.”

Sheldon’s department enjoyed analyzing

behaviours, intentions and affinities, identifying

geographic ‘hotspots’ for artists, and personalizing

and improving the user experience for fans using

their digital assets. Yet he felt - and probably

persuaded himself - that he could add more

value to the business, and increase his influence,

by contributing to discussions on new product

development. His future was bright and the

application of his work appeared limitless.

“In creating new material?”

To move forward this potential expansion of his

role, he found himself ushered into the office of

David Kong, Galaxy’s President. Kong, affectionately

known as ‘King Kong’ reclined deeply in his chair.

“So you’re the ‘Data Man’? As a President /CEO,

I guess I’m seen as a ‘numbers man’, so we have

something in common. I don’t mean ‘Data Man’ in

a patronizing way, I assure you. I love data geeks,

some of my best friends are data geeks, and you’re

making a great contribution to the marketing side of

the business.”

“Thanks. We are supposed to be in The Data Era

now - isn’t everything data-driven these days?”

“In terms of new product development there’s

probably a bunch of things you could do in back

catalogue exploitation. There might be some new

themes you could identify. You know, The Best Geek

Album in the World Ever (sorry). You could also look

“I’m already doing work in that area. I was thinking

about helping some of the bigger acts with new

creative work.”

“There are some acts we manufacture from A to Z,

‘boy band’ type acts, you know, but this is actually a

small proportion of the roster.”

“I think every artist could benefit from the sort of

analysis I provide.”

“Yes.”

“And how would that work?”

“By better understanding tastes and preferences

of audiences, they will be able to better respond to

them.”

King Kong smiled. “How long have you been

crunching numbers here?”

“Six months.”

“And over that time, what extraordinary creative

breakthroughs have emerged from your analysis?”

“I would need to do a bit more work, and I would

be looking to better inform the process. We must

be able to get more sophisticated at this, as other

industries are, and proactively engineer creative

work in our favour, so it’s not just a series of random

casino bets.”

“Even if I gave you a year, do you think you’re ever

going to find God in the data? Do you think Monet’s

Water Lilies, or Van Gogh’s Starry Night suddenly

sprang out of an analysis of art consumers? Do

you think the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s album came

out of some survey data? Or a focus group? Great

art is magic. Great art is extraordinary. Great artists

‘The Data Case’: Did You Find the Voice of God in the Data?: © 2013, 2023 Paul Saintilan & JF Cecillon

3

lead audiences, they don’t respond to them. They

lead out of conviction and passion and inspiration,

and remorselessly innovate, staying ahead of the

audience. The Beatles could have stuck with their

initial success, and been a guitar driven rock and

roll band. But they evolved into a psychedelic band,

a concept album band, they took listeners on a

journey that they couldn’t have imagined. And what

could they really learn from an audience? How is an

audience going to envision and articulate an entirely

new creative direction? So just reflect for a minute

or two Sheldon on what this company and the music

industry really needs today.”

“Well”, replied Sheldon, “if I found the Holy Grail, it

would be how to make hits through a deep insight

into consumer tastes. The second thing I guess is to

do it again and again …?”

“I like your enthusiasm and your ambition Sheldon,

and so don’t take this the wrong way, but your Holy

Grail doesn’t exist. Not so long ago a numbers man

bought the great British record company EMI and

promised his investors that like King Arthur he knew

how to find the Holy Grail. But do you know what

happened? He destroyed one of the world’s oldest

and most successful record companies, lost his

shirt and his investors’ money and EMI was broken

up and sold to the other three big companies. You

talk about technology. The ongoing viability of

this industry is about building on the success of

streaming, to increase the number of people paying

for and accessing music to every corner of the earth.

We also need to develop artists with real longevity to

build the catalogue of tomorrow. How many stadium

acts are we creating these days? Over the last 20

years long term artists have become short-term,

one-hit wonders. Fans have become consumers.

Songs have become sounds. Long-term investment

has become short-term return. Belief in talent has

submitted to belief in data.”

“But there is so much talk these days of a new

model emerging, a participatory, co-creation

model?”

“What you’re giving me is an old model. A derivative,

conservative, sales analysis model, not a cutting

edge artistic leadership model. ‘They liked Ed

Sheeran. The engagement indices are high for Ed

Sheeran. Let’s try to find another Ed Sheeran.’ Doh!”

Sheldon Cybertron looked out of the window

dejectedly. It all seemed so much easier for his

friends working at Procter & Gamble and Unilever.

Their companies really appreciated customer

insight.

Discussion questions:

1. How should customer data and research inform

new product development decisions in music

organizations?

2. What data usage is appropriate and what is

inappropriate in this context?

3. What type of decision-making process is

Sheldon advocating here? Is this an appropriate

practice for the creative industries?

4. To what extent do music fans know what music

they want to discover?’

Sheldon was taken aback. “But technology

is opening up opportunities we haven’t even

discussed. Some artists these days are involving

audiences in their creative processes, interacting

with them. Technology and social engagement are

actually part of their creativity, they use the world as

an orchestra.”

“You know, Sheldon, if we go back to the time of the

Romans or the Middle Ages, every time they were

saying Vox populi vox Dei (the voice of the people

is the voice of God) that was when they didn’t know

what to do! In music, the artist is the voice of God.

This industry has been built on the work of people

who were not normal, not the voice of the people.”

This case appears in the textbook Managing

Organizations in the Creative Economy:

Organizational Behaviour for the Cultural Sector

by Paul Saintilan and David Schreiber. The first

edition was published by Routledge in 2018, and the

second edition is scheduled for 2023. The textbook

examines topics such as decision making and

managing creativity.

‘The Data Case’: Did You Find the Voice of God in the Data?: © 2013, 2023 Paul Saintilan & JF Cecillon

4

The Artistic v. Marketing

Interfunctional Conflict Case

A case study for students studying music organizations in music business

or entertainment management programs.

This case explores interfunctional conflict at the artistic/marketing interface in large music organizations.

Two scenarios are presented where artistic and marketing executives clash, one in a commercial record

company context, and one in a non-profit symphony orchestra context. Students are invited to explore the

underlying issues that drive the tensions.

Keywords: A&R, artistic administration, marketing, interfunctional conflict, artistic/marketing interface,

interdepartmental tension.

Authors: Dr Paul Saintilan & Simon Cahill

The Artistic v. Marketing Interfunctional Conflict Case

© 2013, 2023 Paul Saintilan & Simon Cahill

About the Authors

Dr Paul Saintilan is a creative industries ‘pracademic’,

author, teacher and industry consultant. He has

worked as an international marketing director at EMI

Music and Universal Music in London, as well as in

non-profit roles in classical music organizations.

Simon Cahill is the SVP of Commercial, Media and

Audience of Warner Music Australia. Prior to Warner

Music he has held positions at Sony Music in A&R,

Marketing at BMG and Sales at Mushroom.

This case can be used free of charge for educational

use, without the permission of the authors. It can be

freely distributed in soft or hard copy, or placed on

digital blackboards and online teaching platforms with

no license fee payable.

All characters in this work are fictitious. Any

resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is entirely

coincidental.

Acknowledgements

Designed by Ersen Sen. Images licensed through

Shutterstock. The cover image is by Crazy nook and the

inside strip image is by Chenspec.

Second edition. First edition published by The

Australian College of the Arts (‘Collarts’) in 2013.

The Artistic v. Marketing Interfunctional Conflict Case: © 2013, 2023 Paul Saintilan & Simon Cahill

2

Sam Stossburg, the A&R Vice President at Galaxy

Records sat opposite his marketing colleague in

a meeting room. Tension had arisen over a new

project for which Sam had great expectations, but

which had disappeared from the charts without

trace. “Well it was a hit when it left my desk”

muttered Sam. “What did you do to it? There was no

major marketing and promotional support as far as I

could see. You guys f*#%ed it. You f*#%ed me. You

f*#%ed the band. You guys are f*#%ed.”

The Marketing Vice President Katie Jamieson

smiled. “Yeah, well here’s the thing Sam. Before you

sign an artist, why don’t you come to us for a reality

check and talk to us about the commerciality of the

project, the social metrics, the sort of budget we

have to promote it, and where it’s likely to land in

the market? There was nothing to promote there.

No audience to engage with. We should be in sync

on these things. Single vision. And by the way, the

quality of your analysis doesn’t improve with the

number of F-bombs you drop.”

“It was a disgrace. And I’m the one who has to pick

up the pieces with the band......Now, turning to the

Quantum release, we have a problem in terms of

timing.”

“It’s not slipping?”

“Yes, Katie, it’s slipping. It’s going to fall right out of

Q3 and into the next financial year.”

quarter is the best time to break new music, before

you get into the end of year Christmas / Wrapped

playlist car crash. If you push this release back

you can take an axe to the projections. The other

territories who are depending on this to make their

numbers are also going to scream. You can take

their zoom calls.”

“What do you want me to do? If it isn’t ready, it

isn’t ready. Do you think Beethoven had someone

screaming at him saying ‘If the Moonlight Sonata

isn’t ready by the full moon, you’re not getting

paid?’”

“Some of it must be ready. Can’t we just remix some

of their last album, put out a cover, add a US MC,

waterfall it as a bundle, and keep the release date?

Is it genuinely awful?”

“I like where you’re going with this Katie. Let’s

butcher the integrity of the whole project so in five

years time we can look back and be embarrassed.”

“If we continue blowing our numbers, none of us are

going to be here in one year’s time, let alone five.”

“The artists are going to be here in five years time,

and they’re the ones putting themselves out there,

not us. Do you think the band or manager care if

our annual budget is blown? There’s no contractual

breach. If they deliver it next year, there’s nothing we

can do.”

“But it can’t. We’ve just spent three months putting

together the campaign. This is a big release. If it

slips, the whole annual budget is blown. What’s the

problem?”

“Who writes these contracts?” muttered Katie, “It’s

crazy.”

“It’s just not there. There’s no point in putting out

garbage.”

The Artistic Administrator Natalie Marnier sat

opposite Steve Spring, the orchestra’s new

Marketing Director. She had met the previous day

with the orchestra’s Principal Conductor and Musical

Director, who had expressed grave concerns over

the orchestra’s marketing.

“Well, if we pull it, we’ve burned our bridges with

some pretty key partners. I’ve spent an age doing

the set-up, and a lot of the stuff we’ve organized is a

one shot deal. Some of these influencers and media

partners were doing us a favour, so it’s not like that

support is going to be there if we reschedule. This

Meanwhile, on the other side of town....

“Maestro Cellini isn’t happy with the draft season

brochure.”

The Artistic v. Marketing Interfunctional Conflict Case: © 2013, 2023 Paul Saintilan & Simon Cahill

3

“OK”

“There are some things he says you’ve ‘dumbed

down’. You edited down his opening page, removing

a lot of information and credits.”

“Between you and me it was boring. No one cares. A

lot of that stuff should be at the back of the brochure

in micro type.”

“But I agree with him that it damages morale among

team members if they’re not being acknowledged.

A mention is a small thing in a brochure, but can

mean a lot to the person being credited. And you

deleted his comments on the music. Your short

little summaries for each event are too glib and

simplistic.”

“His writing is too musicological. Too technical. Too

jargonistic. Too long. We should be writing more

experientially about the music, about how it makes

you feel. We need to give a richer context that is

going to help shape the listener’s experience, and

help them relate to the program, even if they know

nothing about classical music.”

“But we’re not after just anyone. We’re after

thinking, active listeners who are going to make

an investment in the experience. We’re not going

after some mainstream pop audience with the

attention span of sparrows. Our core audience are

knowledgeable and will feel patronized by what

you’re writing.”

“If you want to keep the audience to a closed club of

dying subscribers, then sure, we can do that, but you

will be the last one left here to switch the lights off.”

She looked further down her list. “And we took six

months to get a photo of the Russian soprano, and

you didn’t even put it in.”

“It was hideous! She looked like her eyes were

going to pop out of her head, hitting a high note.

It gives me nightmares just thinking about it. Who

does the photos for these artists?!”

“And by the way, I would be really grateful if you

didn’t use the word ‘product’. That language is quite

offensive to some of us. Turning someone’s most

personal, spiritual, artistic quest into some plastic

commodity, like a tube of toothpaste, it’s just crass

and awful.”

“Fine. I’ll add that to ‘brand’, ‘content’, ‘NFT’, ‘NPD’,

‘CRM’, and all the other terms I’m banned from using

here.”

“Also, Maestro complained that in the printed

concert program last night you had minutes against

each of the movements.”

“It helps orientate newcomers so they know roughly

where they are in the program. Newbies need

assistance to help them navigate the experience.

This stops them clapping between movements,

which I know really offends you, even though when

I hear clapping between movements I am relieved,

because it means we have some new people in the

hall.”

“The thing that offends Maestro is that he may want

to take 13 minutes for a movement rather than the 10

minutes stated in the program. He is not a machine.

He doesn’t want to be artistically defined by your

prescriptions and pronouncements.”

“He doesn’t have to. They’re just general

indications.”

“And your advertisements communicate at the most

banal, superficial level. It’s a missed opportunity

because there’s so much more we could be

communicating, which I’m sure would be better

marketing. Sometimes you don’t put all the artists, or

all the composers, or there isn’t any information at all

on some really important things.”

“Natalie, the media environment is so competitive

and cluttered, you have to reduce things to one

clear, simple proposition, or you make no impact.

Artistic Administration always wants a hundred

things put across in a 30 second TV spot, or a

print ad in a magazine or a social media post. Less

is more. We need to make one clear, compelling

statement. I’m happy for you to help define that

statement.”

“But I’m the one who needs to manage disgruntled

artists who see themselves increasingly ignored

by you in the process. Or steamrolled by your

arrogance. You may be following your marketing

textbooks, but it is pretty naïve politically to do what

you’re doing. You’re annoying some pretty important

people.”

“I’m just fighting my corner, fighting it hard, and

doing what a Marketing Director is supposed to do.

Others like the Managing Director can arbitrate, and

I’ll live with their decisions.”

“Well Maestro isn’t happy, and he says he will be

talking to the Managing Director.”

The Artistic v. Marketing Interfunctional Conflict Case: © 2013, 2023 Paul Saintilan & Simon Cahill

4

Discussion questions:

1. Examine the points of conflict in the case. What

are the underlying issues that are driving the

tensions?

2. Are these tensions at the artistic / marketing

interface natural and inevitable? Can steps be

taken to improve organizational effectiveness

and the relationship between the two functions?

This case appears in the textbook Managing

Organizations in the Creative Economy:

Organizational Behaviour for the Cultural Sector

by Paul Saintilan and David Schreiber. The first

edition was published by Routledge in 2018, and the

second edition is scheduled for 2023. The textbook

examines topics such as organizational conflict,

interfunctional tension, and managing creativity.

The Artistic v. Marketing Interfunctional Conflict Case: © 2013, 2023 Paul Saintilan & Simon Cahill

5

The International Meeting

A case study for students studying music organizations in music business

or entertainment management programs.

This case explores issues such as the organizational tension that occurs between centralization and

decentralization, and tensions that arise between head offices and branches.

Keywords: centralization, decentralization, structure, multinational, creativity, head office and branch tensions

Authors: Paul Saintilan, Michael Smellie & Cindy James

The International Meeting Case

© 2013, 2023 Paul Saintilan, Michael Smellie

& Cindy James

About the Authors

Dr Paul Saintilan is a creative industries ‘pracademic’,

author, teacher and industry consultant. He has

worked in international roles at EMI Music and

Universal Music in London as well as non-profit roles

in classical music organizations.

Michael Smellie is the former chief operating officer

of Sony BMG worldwide.

Cindy James has worked for Sony Music in Sydney,

London and New York, and now works for Virgin

Music Label & Artist Services/Universal Music Group.

This case can be used free of charge for educational

use, without the permission of the authors. It can be

freely distributed in soft or hard copy, or placed on

digital blackboards and online teaching platforms

with no license fee payable. Feedback would be

appreciated on the case (via paulsaintilan@gmail.

com). Readers who provide suggestions which are

incorporated will receive acknowledgement in future

editions of the case.

All characters in this work are fictitious. Any

resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is

entirely coincidental.

Designed by Ersen Sen. Images licensed through

Shutterstock. London image Pisa photography/

Shutterstock.com.

Second edition. First edition published by The

Australian College of the Arts (‘Collarts’) in 2013.

The International Meeting Case: © 2013, 2023 Paul Saintilan, Michael Smellie & Cindy James

2

“Impossible! This won’t work in my market. Just

because something explodes in Norway doesn’t

mean it will translate to France.” Executives working

at an international record company argue about the

freedom to pursue local priorities and the impact of

increasing centralization.

Tom Black glanced around the boardroom

overlooking Hyde Park, London, which was abuzz

with around twenty international delegates who

had flown in the previous evening. All were senior

managers of Galaxy Music, an international record

company and concert promoter. Big changes were

underway at Galaxy, as Black, the newly appointed

worldwide president, was pushing hard for greater

centralization of the organization. Traditionally they

had operated a decentralized, ‘federated’ structure,

with geographic territories such as the US, UK and

Germany run as separate companies with enormous

freedom. Each had the power to make their own

business decisions in terms of who to record or tour,

and which artists to support that had already been

developed by other operating companies. In this

internal market, if Galaxy UK developed and broke

an artist in the UK, Galaxy Germany could choose to

promote the artist in Germany, receiving the revenue

from German sales and paying the UK company

a royalty. The worldwide president had recently

imposed far greater centralized control, a step that

had angered some staff. This meeting had been

convened to both reinforce that control and address

the growing hostility.

Black sensed a lull in the conversation and decided

to open the meeting.

‘OK, let’s begin. Welcome everyone. I know you’re

all flat out and these meetings are tough to make

time for, but it’s vital that we’re all aligned and all

our planning is synchronized. This is also your

opportunity to help define the future of the company.

Your collective judgements and sales projections

provide us with a mandate to pursue future projects

and move into new areas. It is also an opportunity

for us to spend a bit of social time together, and

I know the UK company has put together a great

evening programme for us. So that’s something

to look forward to.’ Noticing a few still playing with

their phones, he added, ‘And it would be great if

you could power down your devices so you’re really

present in the room for the discussions, rather than

mentally thousands of miles away’.

‘One theme I would like to pursue today is more

unified support for those projects which are

designated international priorities. For us to be able

to make commitments to major artists and major

projects we need you to back us. If we can’t count

on that, it compromises our ability to pitch for major

projects, it reduces our international competitiveness

and it means we can’t fully maximize the potential

of our artists. In an increasingly global music market

we need to break artists and projects internationally,

and build international catalogue for the future.

An online world also makes old geographic silos

meaningless. We need increasingly centralized

management and the coordinated marketing of

international projects.’

Alain Legrand, the veteran managing director of

the French company, quickly interjected before the

president went further.

‘Thank you so much, and may I say how good it is

to be here with my old international colleagues in

London this morning. I would just like to ask whether

in this new world, we as local companies will still

be able to make our own business decisions, to

respond quickly and flexibly to local opportunities,

local tastes and local talent. One thing I have always

loved about working in this company is that I felt like

I was running my own business within the bigger

business. I felt like I had the space and freedom

to do my own thing. I feel more recently the dead

hand of centralization, formalization, standardization,

rigidity, all of these things which we know are

hostile to creativity. And for me it is a great sadness,

because we work in a creative business. How

can you reassure us that these new steps will not

damage the company?’

‘Thanks Alain. Look, like you, we want a company

of entrepreneurs, not a company of nine to

five employees. We want you to feel a sense

The International Meeting Case: © 2013, 2023 Paul Saintilan, Michael Smellie & Cindy James

3

of ownership in your local company and your

decisions. We want you to be handsomely rewarded

for your successes, and held accountable for your

failures, and this is only fair when you are living and

dying by your own decisions. I’m not talking here

about your day to day business of identifying local

projects which are evolving organically through

social media which you might take to the next level.

You don’t need any directives from me to pursue

these. I’m talking about superstar acts we need to

see the full company behind, those projects where

we see so much evidence of potential we seek

to maximize it internationally. Where we believe

it makes international sense to become market

makers and drivers in some territories, rather than

being purely reactive. We need to keep an eye on

the bigger picture. We want you to think global and

act local. We’re after a balanced win/win.’

‘But I don’t think we are in balance, or maybe what

is “balance” for you, is not “balance” for me’ replied

Legrand. ‘Our market has idiosyncrasies which

need to be respected, and which change the risk

profile and return on investment. Furthermore,

every day we receive some new directive of things

that now need to be done differently, things which

now need to be centrally authorized, policies and

strategic plans that have to be developed for

everything. Increasingly we have all these new

people from head office (most of whom don’t

appear to have worked in the music industry I

might add) strangling my staff with bureaucracy

and red tape. They tell us the new organization

will still be “organic”, “fluid” and “responsive”, but

then overwhelm us with requests for reports on a

million things. Instead of my people spending time

on things which would drive the business forward

and help deliver our numbers, they’re compiling

piles of statistics for some new intern. And when

my staff complain, they are ignored. Maybe we

should not create and sell music anymore, because

it is getting in the way of all the very important form

filling work we should all be doing.’

Black smiled. ‘We have taken on some new staff.

They’re all keen to show how much they can

contribute to the business, and so we might not

be dealing with you in the most coordinated way,

and they might not be aware of the opportunity

cost of these tasks. So, let me go away and review

what we’re doing and see if we can do it better.

And thank you for raising it, Alain, because I know

you are very respected in the organization, and I

want you all to feel comfortable raising problems,

so we can try to resolve them. Now let’s turn to the

Bangkok Project. I’m interested in twelve-month

projections for the next calendar year in terms of

Track Equivalent Albums. You’ve previously been

sent the material. Katie?’

Katie Jamieson, the US marketing manager, looked

up from her iPad. ‘Well, we’re pretty comfortable with

this one, because, as you know, the artists will be

based in New York for three months, they all speak

English, and they’re all committed to promotion. In

fact, the hardest part is getting them not to promote

it themselves, but to hold back until everything is

in place. It’s all pretty strong, the visual identity,

video material, the social metrics, the back stories

and narratives being woven around it, the whole

package. So, we don’t see any reason to change the

initial projections that are in the spreadsheet, and

we believe it’s a viable investment.’

‘Great, thanks, Katie. What about the French market,

what sort of numbers?’

Philippe Collard, the marketing director for Galaxy

France, who sat next to Legrand, paused and shook

his head.

Black sensed a problem. ‘Let me guess, this project

is an affront to the entire French nation, and you

would be run out of Paris if you backed it?’

‘What can I say? You ask me to be honest. It’s

impossible. There is no respect in France for this

type of project. There is no real social footprint in

France that could serve as a platform for this project.

There is limited availability from the artists, not to

mention language barriers. Just because something

explodes in Norway or Shanghai or Albuquerque

doesn’t mean it’s going to work in France. We must

pass. Throwing money at this project would be

throwing good money down the drain. It also means

with the tight new budgets that have been imposed,

that we have less to spend on artists who we know

will be successful in France. This seems like a lose/

lose, not a win/win.’

Black responded: ‘The problem is that if I give

you a free pass to opt out, we set a precedent

for others as well. We’re then not doing the hard

yards around international artist development.

We’re not setting ourselves up for the future. I’m

the one who needs to look an artist in the eye and

say “the entire organization is behind you on this

one”, and “we are the best company to be the

home for this project”. And then they come to Paris,

and they see nothing, and they’re on the phone

screaming at me. Sure, there are going to be times

when we can get music away in some territory

that won’t break in another, but all I’m asking you

to do is try. No one has perfect knowledge of their

The International Meeting Case: © 2013, 2023 Paul Saintilan, Michael Smellie & Cindy James

4

market. There is always something that surprises

us. But if you’re not pushing the envelope and

experimenting, you leave yourself a hostage to

fortune. If you don’t support something that is

highly successful elsewhere, and you’re not trying

to be a team player, it just makes your territory

look poor in comparison, and before long people

are whispering “what’s the problem with France?”,

which is never healthy for the executives involved.

We respect a company’s right to make their own

decisions about local artists and repertoire, but

for the small category of releases designated

international priorities, the situation is quite

different. I am not politely suggesting that you

release it. We mandatorily require its promotion

in all territories, and everyone in this room will be

sending us a serious marketing plan for the project

with sales projections.’

Black reached across and poured himself an Evian.

He knew that with those words the tone of the

meeting had changed, and caught a raised eyebrow

or two. But how was he to pull together a company

that had for so long been run like a group of

sovereign states or fiefdoms?

This case appears in the textbook Managing

Organizations in the Creative Economy:

Organizational Behaviour for the Cultural Sector

by Paul Saintilan and David Schreiber. The first

edition was published by Routledge in 2018, and

the second edition is scheduled for 2023. The

textbook examines structural concepts and trends in

structuring creative organizations.

Discussion questions:

1. List the strengths and weaknesses of

centralization versus decentralization at Galaxy.

2. What could Galaxy do to ease the tension

between the international head office and the

operating companies (i.e. geographic branches

like France)?

The International Meeting Case: © 2013, 2023 Paul Saintilan, Michael Smellie & Cindy James

5

The Three Tenors

Antitrust Case:

What Did We Learn?

A case study for students studying music organizations in music business

or entertainment management programs.

“PolyGram Holding”, commonly known as “The Three Tenors Case” has been one of the most cited antitrust

(anti-competitive) cases of the past twenty years, yet the discussion has been largely confined to legal

journals and the U.S. antitrust community. What can managers in large commercial music and entertainment

organizations learn from the case? What are the practical implications? The paper argues that the case

influences the conceptualization and structuring of certain types of joint venture deals, and that the core

problem initially arose from attempting to address an internal conflict of interest issue within PolyGram. The

case also demonstrates the confusing nature of antitrust law for a practicing music manager.

Keywords: antitrust, anti-competitive behavior, Federal Trade Commission, joint venture, major record

company, PolyGram Classics and Jazz, PolyGram Holding, The Three Tenors

Author: Paul Saintilan

The Three Tenors Antitrust Case: What Did We Learn?

© 2013, 2023 Paul Saintilan

About the Author

Dr Paul Saintilan is a creative industries ‘pracademic’,

author, teacher and industry consultant. He has

worked as an international marketing director at EMI

Music and Universal Music in London as well as in nonprofit roles in classical music organizations.

This case can be used free of charge for educational

use, without the permission of the author. It can be

freely distributed in soft or hard copy, or placed on

digital blackboards and online teaching platforms with

no license fee payable. Correspondence on the case

can be directed to Dr Paul Saintilan via paulsaintilan@

gmail.com.

Acknowledgements

Designed by Ersen Sen.

This article was first published in the Journal of the

Music & Entertainment Industry Educators Association

(MEIEA) in 2013 (Volume 13, number 1, pages 13-25).

The Three Tenors Antitrust Case: What Did We Learn?: © 2013, 2023 Paul Saintilan

2

Preface

The attached article on the Three Tenors Antitrust

Case was published 10 years ago, 15 years after the

events in question. I should disclose as the author

that my research and analysis drew upon more than

third party references. I was in fact a star witness in

the Three Tenors Trial, the ‘point person’ between

the two joint venture parties (Decca/PolyGram

and Atlantic/Warner), the person behind the key

documentation which the FTC seized upon and

quoted extensively in their action.

As the marketing director at Decca responsible for

Pavarotti releases, and the project manager for the

Three Tenors release, I was responsible for issuing

directives which lay at the heart of the case. While

I was ‘acting under orders’, I personally believed in

the legitimacy of what was being asked of me, which

is why I was happy to comply and why I eventually

supported PolyGram’s legal defence. This involved

participating in a deposition in Los Angeles and a

trial in Washington.

When I wrote up the case from an academic

viewpoint I tried to sit on the mountaintop and

explore more objectively what we actually learned. I

was surprised and reassured by the number of legal

academics and antitrust experts who I discovered

had criticized the FTC’s position on the case. In

discussing the case in an educational context I

was also reassured by the number of students

who found the judgement counter-intuitive. Even

now there are aspects of the FTC’s position that

are contested. It remains a fascinating case, still

generating controversy all these years later.

Paul Saintilan, May 2022

While a general manager can judge whether a

decision makes business sense, and hopefully

whether it is ethical, the legalities are sometimes

more technical, particularly in the area of antitrust

law. The fact that business affairs (legal) executives

attended all our joint venture meetings didn’t stop us

getting into difficulty.

When managing the project I had minuted things

to both joint venture parties meticulously, not just

as professional practice, but as a precaution if

the project bombed and the joint venture partner

sought to scapegoat me. I wanted to ensure critical

decisions we made together were transparently and

explicitly recorded. But in an industry where official

‘minutes’ once meant a few scribbles on the back

of a drink coaster, these notes were manna from

heaven for the FTC when they decided to pursue

the case.

The Three Tenors Antitrust Case: What Did We Learn?: © 2013, 2023 Paul Saintilan

3

Journal of the

Music & Entertainment Industry

Educators Association

Volume 13, Number 1

(2013)

Bruce Ronkin, Editor

Northeastern University

Published with Support

from

The Three Tenors Antitrust Case:

What Did We Learn?

Paul Saintilan

Australian College of the Arts (“Collarts”)

Abstract

“PolyGram Holding,” commonly known as “The Three Tenors Case”

has been one of the most cited antitrust (anti-competitive) cases of the past

ten years, yet the discussion has been largely confined to legal journals

and the U.S. antitrust community. What can managers in large commercial music and entertainment organizations learn from the case? What are

the practical implications? The paper argues that the case influences the

conceptualization and structuring of certain types of joint venture deals,

that the core problem initially arose from attempting to address an internal

conflict of interest issue within PolyGram, and the case demonstrates the

confusing nature of antitrust law for a practicing music manager.

Keywords: antitrust, anti-competitive behavior, joint venture, major

record company

Abbreviations

FTC - the U.S. Federal Trade Commission

JV - Joint Venture

3T1 - The Three Tenors 1990 album released by PolyGram

3T2 - The Three Tenors 1994 album released by Warner

3T3 - The Three Tenors 1998 album released by PolyGram and Warner

Introduction

One of the unforeseen aspects of the Three Tenors legacy is that the

franchise has been elevated to star status in the U.S. antitrust community

(Verschelden 2007). This group of legal boffins is a niche audience admittedly, but the enthusiasm of their analysis has been noteworthy. The

Three Tenors case has been extolled as an important development, clarifying the way certain legal principles will be applied in examining anticompetitive behavior in a joint venture context, with implications for future

cases (McChesney 2004; Meyer 2010; Verschelden 2007). But of what

relevance is this to managers working in music organizations?

This article will provide the background to the Three Tenors case,

MEIEA Journal

13

summarize the court case, the ruling of the Federal Trade Commission

(hereafter referred to as the FTC), the backlash that ensued from lawyers

and law professors, the 2005 appeal, and the backlash to the appeal decision. It will then provide some organizational analysis to look more deeply

at how the problems arose, before turning finally to what can be learned

from the case and its practical implications for music and entertainment

managers.