HFC Network

Bandwidth Usage of Popular Video Conferencing Applications on a 50/10 Mbps Service Tier

As we enter the new year, consumers, workplaces, and schools continue to rely on video conference applications. We previously studied Bandwidth Usage of Popular Video Conferencing Applications in November 2020 and February 2021. In May 2021, we studied Hourly Data Consumption of Popular Video Conferencing Applications. Today, we share a study of bandwidth usage on a 50Mbps/10Mbps Service Tier by popular video conferencing applications and how they perform with the addition of background traffic in the upstream.

This blog is a snapshot of the conference applications' bandwidth usage in December 2021.

The current testing used a 50 Mbps downstream and 10 Mbps upstream service tier, which doubles the upstream speed from the previous work with a 50/5 Mbps tier. With the faster upstream tier, this effort looks at both

- Bandwidth consumed for 10 concurrent conference sessions, and

- The behavior of 10 concurrent conference sessions in the presence of additional upstream traffic, specifically an upstream 5 Mbps UDP (user datagram protocol) flow.

Apple FaceTime, Google Meet, and Zoom were examined. When possible, we tested the available desktop version of each video conference application. To avoid any appearance of endorsement of a particular conferencing application, we do not label the figures below with the specific application under test. As described below, in the presence of the 5 Mbps UDP flow in the upstream the three applications behave similarly and without any negative impact to the video-conferencing application.

In addition to the video conferencing streams, we add a 5 Mbps UDP stream of upstream traffic in the background to illustrate the capability of a 10 Mbps upstream tier. Besides video conferencing applications, other popular activities that drive upstream usage are online gaming, Wi-Fi connected cameras, and file uploads. The additional 5 Mbps stream is meant to capture a wide range of common use cases. For example, concurrent use of one to two online gaming sessions (100 to 500 Kbps each), three to four Wi-Fi connected cameras (500 Kbps to 1 Mbps each), and a file upload of 2 Mbps (900 megabytes over an hour) would all fit within this 5 Mbps upstream budget. As we show below, even with this 5 Mbps traffic and 10 concurrent sessions of the video conferencing applications, there is still upstream bandwidth available for additional activity by a subscriber with a 50 Mbps/10 Mbps service tier.

The lab setup was modified from our previous testing. The ten laptops used during this testing were different than the previous blogs; this group of laptops consisted of five MacOS and five Windows 10 operating systems. The laptops were standard consumer grade laptops without any upgrades such as those commonly used by gamers.

What did not change is the same DOCSIS 3.0 Technicolor TC8305c gateway and same CommScope E6000 cable modem termination system (CMTS) from the previous testing were used during this testing. Additionally, like the previous testing, all the laptops used wired Ethernet connections through a switch to the gateway to ensure no variables outside the control of the broadband provider would impact the speeds delivered (e.g., all the variables associated with Wi-Fi performance). Throughout testing, we ensured there was active movement in view of each laptop’s camera to simulate real-world use cases more fully.

As in the previous blogs, this research does not consider the potential external factors that can affect Internet performance in a real home -- from the use of Wi-Fi, to building materials, to Wi-Fi interference, to the age and condition of the user’s connected devices -- but it does provide a helpful illustration of the baseline capabilities of a 50/10 Mbps broadband service.

As before, the broadband speeds were over-provisioned. For this testing, the 50/10 broadband service was over-provisioned by 25%, a typical cable operator configuration for this service tier.

To establish a baseline, we began by repeating the data collections from the three previous efforts and were able to confirm the results. In the seven months since our last testing, many of the application developers issued updates to the applications, thus we compared the current observations with past observations looking for consistency instead of identical results.

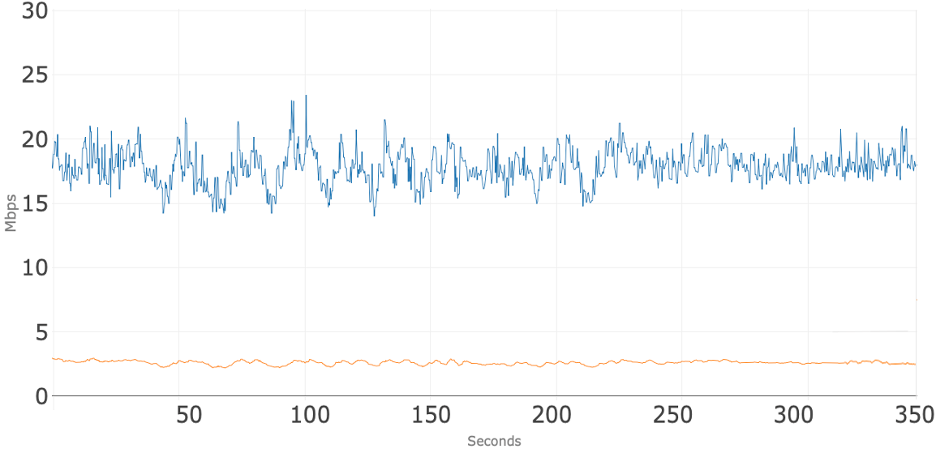

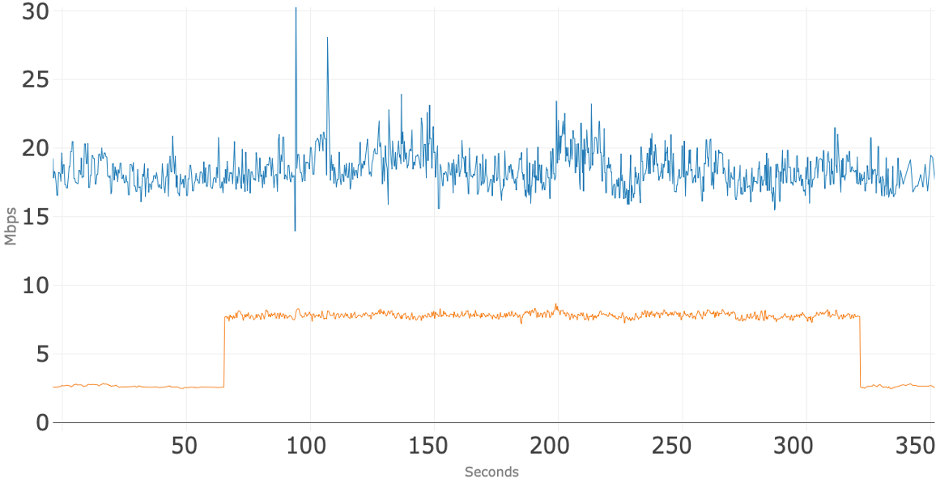

Conferencing Application A

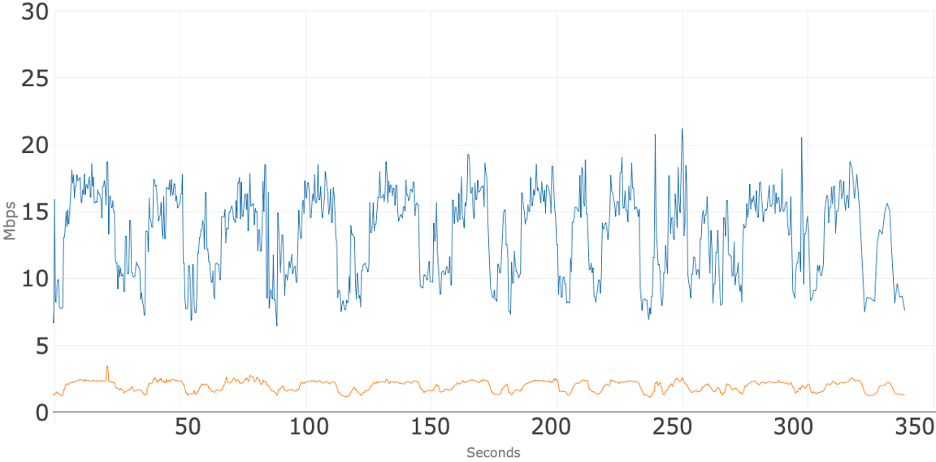

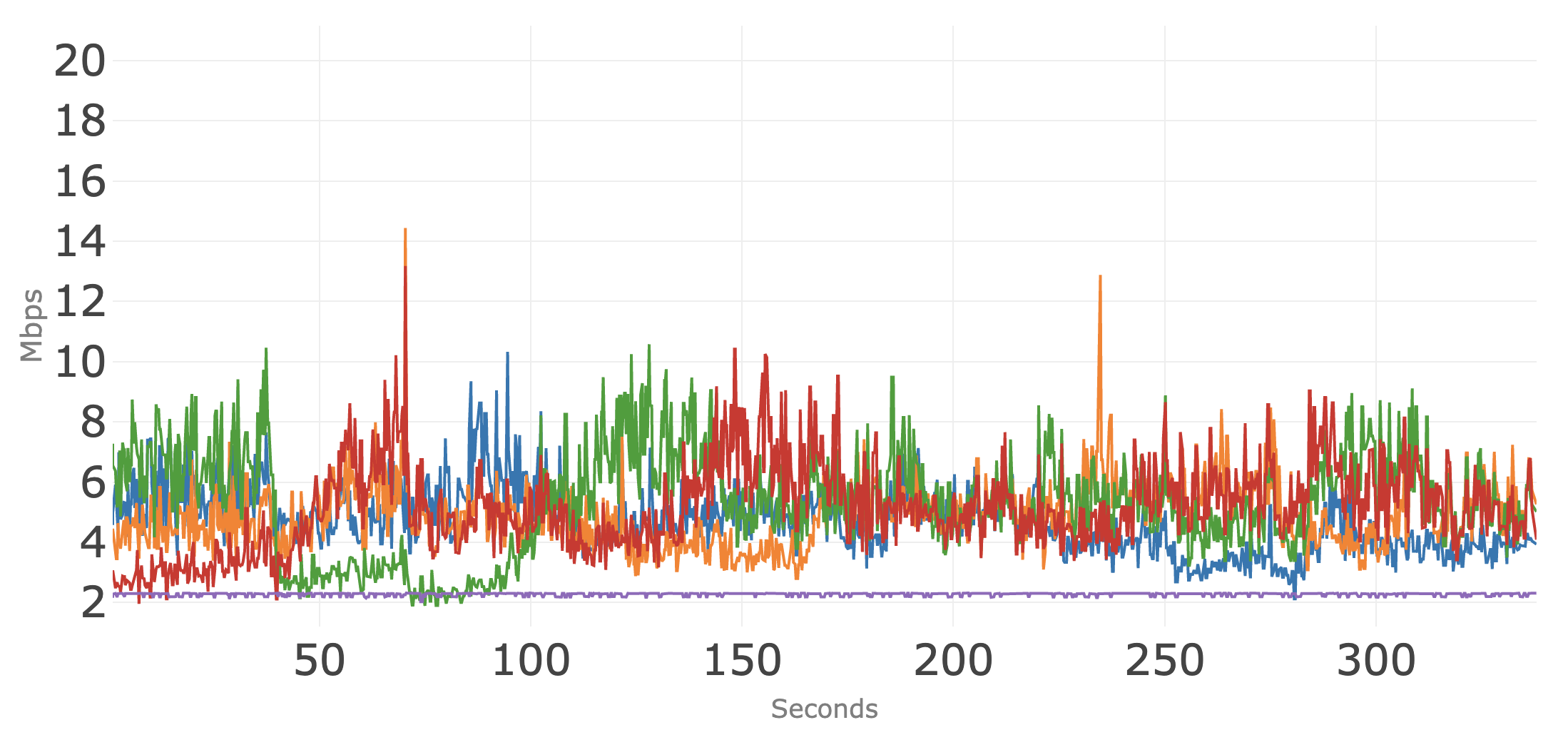

Figure 1 shows total access network usage for the 10 concurrent sessions over 350 seconds while using App A. The blue line is the total downstream usage, and the orange line is total upstream usage. Note that even with a 10 Mbps upstream tier, the total upstream usage stays around 2.5 Mbps. The downstream usage stays, on average, around 18 Mbps, which leaves roughly 32 Mbps of downstream headroom for other services, such as streaming video, that can use the broadband connection at the same time.

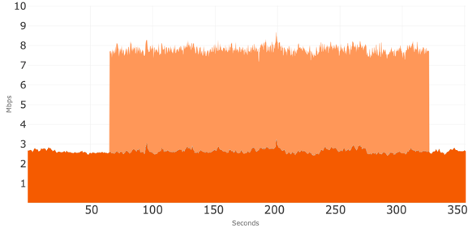

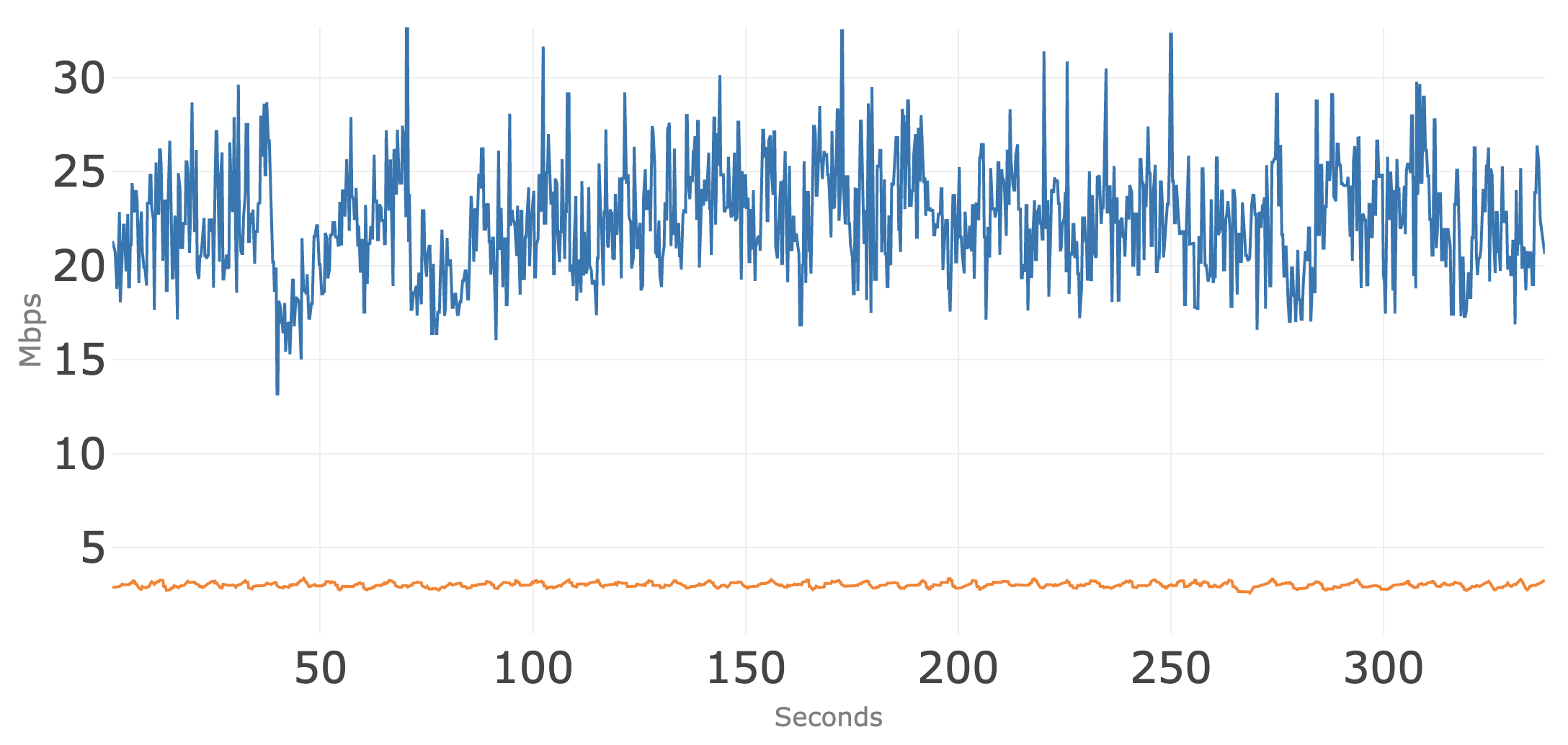

Figure 2 shows total access network usage for the 10 concurrent sessions and the addition of 5 Mbps of upstream traffic over 350 seconds while using App A. The blue line is the total downstream usage, and the orange line is total upstream usage. Note that before the upstream 5 Mbps was applied the total upstream usage was around 2.5 Mbps. At about 60 seconds, the additional 5 Mbps UDP stream was added to the upstream which causes the total to increase to about 7.5 Mbps. As shown in Figure 3, the addition of 5 Mbps of traffic causes no noticeable impact on the upstream conference flows. At about 320 seconds that 5 Mbps stream is removed, and the upstream usage goes immediately back to where it was before that stream was applied. During the entire test the downstream usage stays, on average, around 18 Mbps even when the additional upstream bandwidth is consumed.

Figure 3 shows just upstream usage where the upstream traffic for the 10 concurrent sessions of App A is shown with dark orange, and the additional 5 Mbps of upstream traffic is shown in light orange. This view emphasizes that the additional 5 Mbps of upstream traffic does not appear to have an impact on the upstream bandwidth usage of the 10 concurrent video sessions of App A.

Conferencing Application B

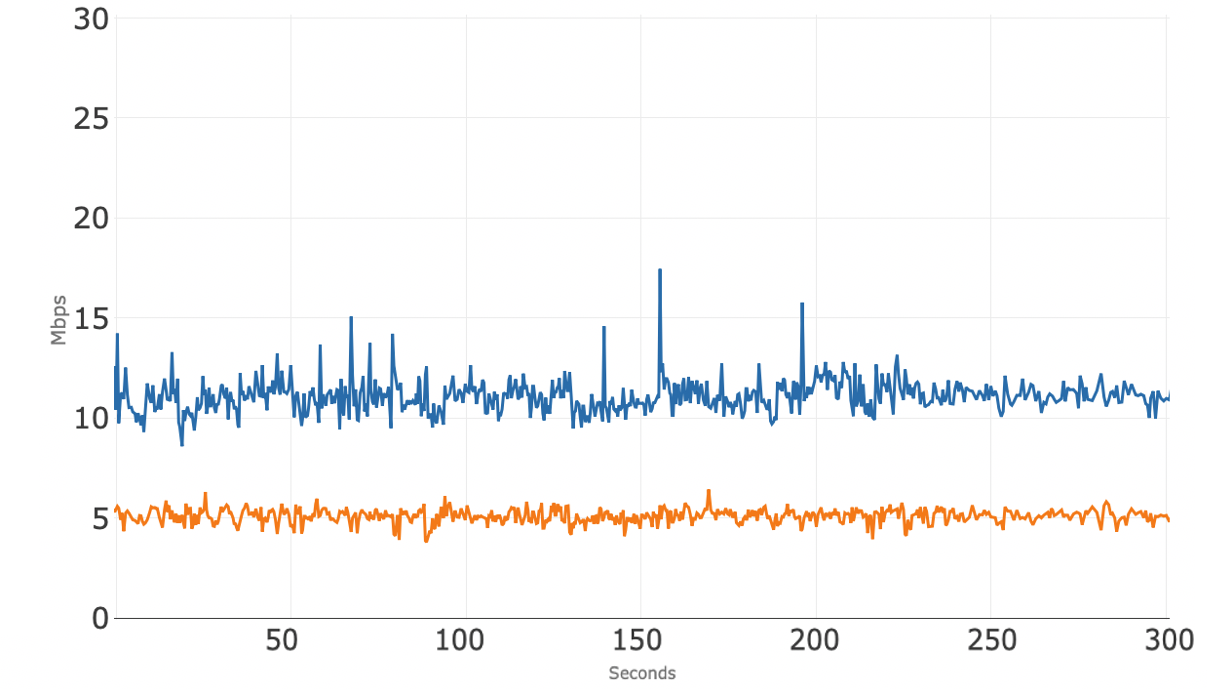

Figure 4 shows total access network usage for the 10 concurrent sessions over 350 seconds while using App B. The blue line is the total downstream usage, and the orange line is total upstream usage. Note that even with a 10 Mbps upstream tier, the total upstream usage stays under 2.5 Mbps. The downstream usage stays, on average, around 13 Mbps, which leaves roughly 37 Mbps of downstream headroom for other services.

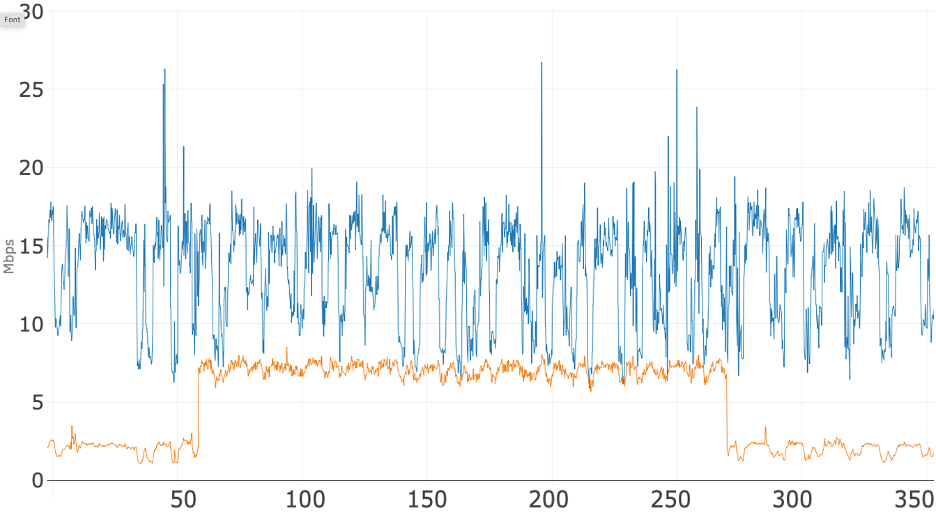

Figure 5 shows total access network usage for the 10 concurrent sessions and the addition of 5 Mbps of upstream traffic over 350 seconds while using App B. The blue line is the total downstream usage, and the orange line is total upstream usage. Note that before the upstream 5 Mbps was applied the total upstream usage was around 2.5 Mbps. At about 60 seconds, an additional 5 Mbps stream was added to the upstream which causes the total to increase to about 7 Mbps. As shown in Figure 6, the addition of the 5 Mbps of traffic causes no noticeable impact on the upstream conference flows. At about 270 seconds that 5 Mbps stream is removed, and the upstream usage goes immediately to where it was before that stream was applied. During the test the downstream usage stays, on average, around 13 Mbps even when the additional upstream bandwidth is consumed.

Figure 6 shows just upstream usage where the upstream traffic for the 10 concurrent sessions of App B is shown with dark orange, and the additional 5 Mbps of upstream traffic is shown in light orange. This view demonstrates that the additional 5 Mbps of upstream traffic does not appear to have an impact on data usage of the 10 concurrent video sessions of App B.

Conferencing Application C

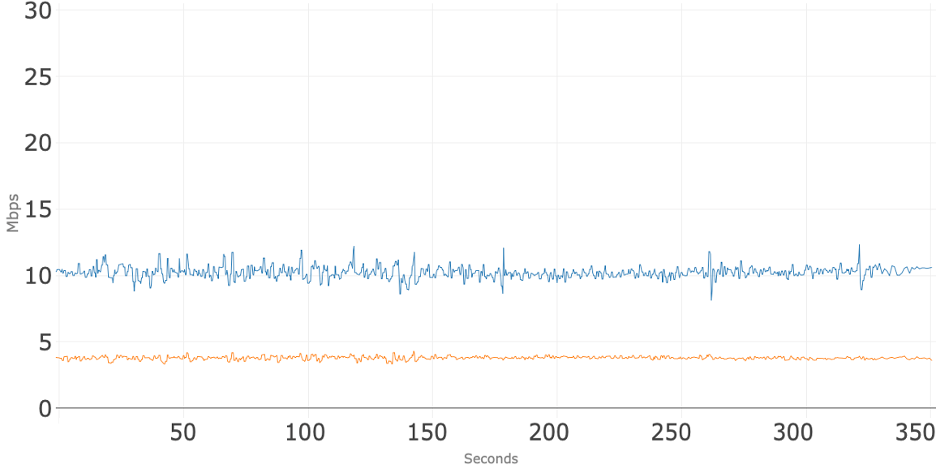

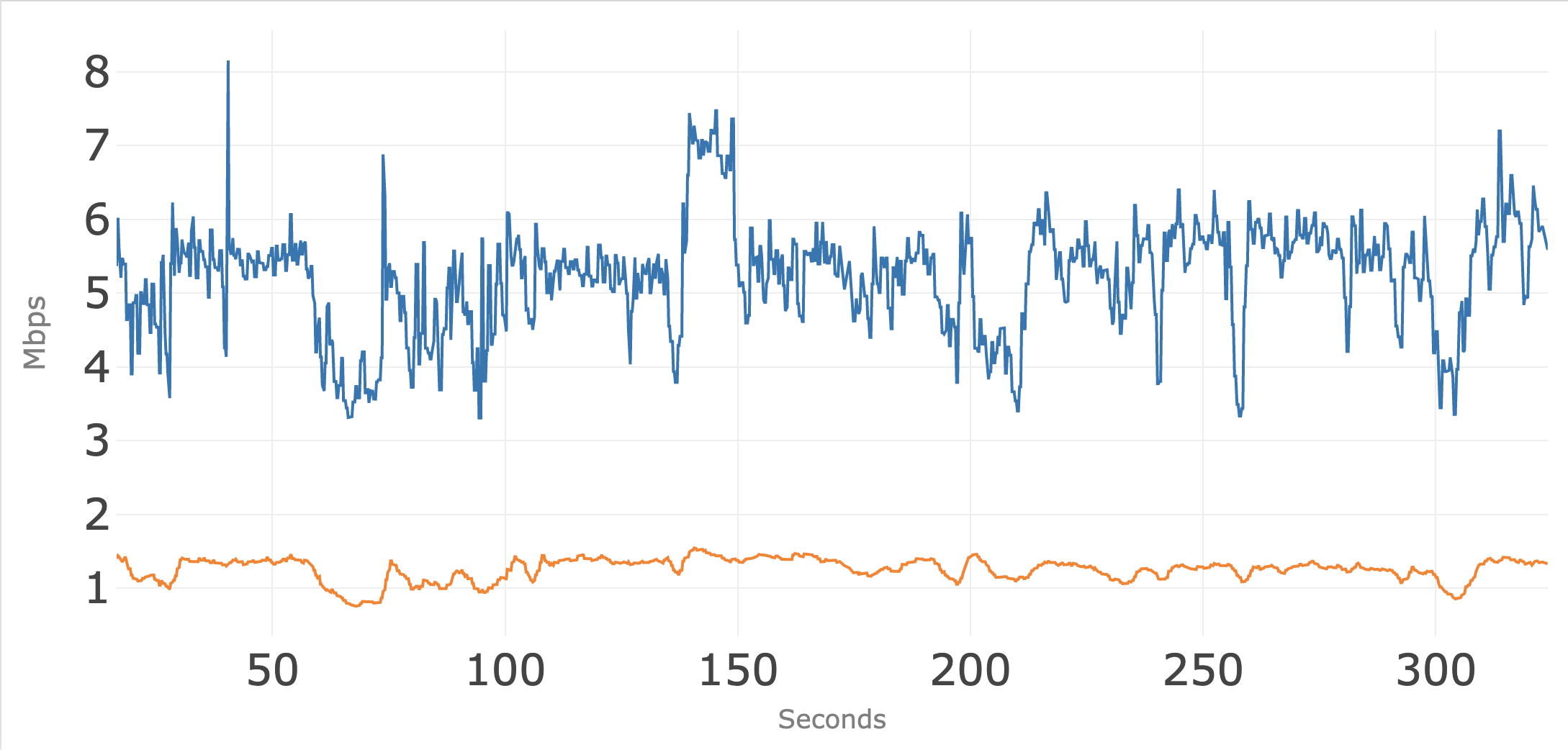

Figure 7 shows total access network usage for the 10 concurrent sessions over 350 seconds while using App C. The blue line is the total downstream usage, and the orange line is total upstream usage. Note that even with a 10 Mbps upstream tier, the total upstream usage stays around 4 Mbps. The downstream usage stays, on average, around 10 Mbps, which leaves roughly 40 Mbps of downstream headroom for other services.

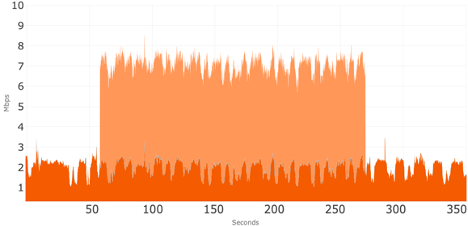

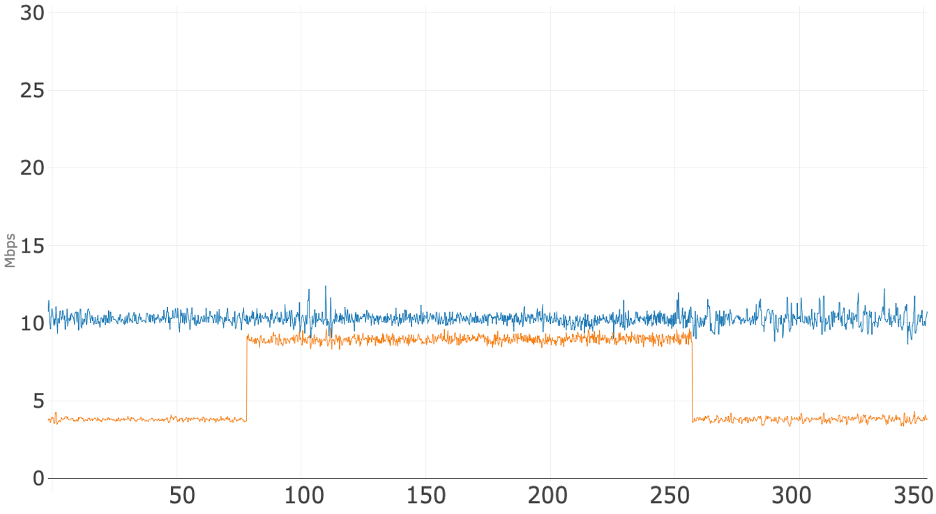

Figure 8 shows total access network usage for the 10 concurrent sessions and the addition of 5 Mbps of upstream traffic over 350 seconds while using App C. The blue line is the total downstream usage, and the orange line is total upstream usage. Note that before the upstream 5 Mbps was applied the total upstream usage was around 4 Mbps. At about 70 seconds, an additional 5 Mbps stream was added to the upstream which causes the total to increase to about 9 Mbps. As shown in Figure 9, the addition of the 5 Mbps of traffic causes no noticeable impact on the upstream conference flows. At about 260 seconds that 5 Mbps stream is removed, and the upstream usage goes immediately back to where it was before that stream was applied. During the entire test, the downstream usage stays, on average, around 10 Mbps even when the additional upstream bandwidth is consumed.

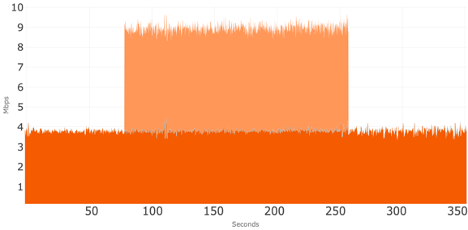

Figure 9 shows just upstream usage where the upstream traffic for the 10 concurrent sessions of App C is shown with dark orange, and the additional 5 Mbps of upstream traffic is shown in light orange. This view demonstrates that the additional 5 Mbps of upstream traffic does not appear to have an impact on the data usage of the 10 concurrent video sessions of App C.

Summary

This investigation looked at three popular video conferencing applications over an upstream tier of 10 Mbps and a downstream tier of 50 Mbps.

The three applications exhibited similar behavior of using under 4 Mbps of upstream during 10 concurrent conference sessions. When an additional 5 Mbps of upstream traffic was added, these three conference apps took it in stride; there were no noticeable changes to either the upstream or downstream consumption of the 10 concurrent conference sessions and no negative impact to the quality of the video conferencing sessions.

The successful testing of 10 concurrent video sessions plus 5 Mbps of additional background traffic illustrates the capability of a 50/10 service tier to support the broadband needs of telework, remote education, telehealth, and other use cases that rely heavily on video conferencing applications. The testing also illustrates that a 50/10 service tier can readily support a household with multiple users engaging on video conference platforms as well as support other simultaneous uses.

HFC Network

Hourly Data Consumption of Popular Video Conferencing Applications

Building on our prior work, this investigation explores the hourly data consumption of popular video conferencing applications: Google Meet, GoToMeeting, Microsoft Teams and Zoom. As video conference applications have become an integral part of our daily lives, we wanted to not only better understand the bandwidth usage as previously explored, but also the total data consumption of these applications. This investigation provides a first step in better understanding that latter dimension. To avoid any appearance of endorsement of a particular conferencing application, we have not labeled the figures below with the specific apps under test. In short, we observed that a single user on a video conferencing application consumed roughly one gigabyte per hour, which compares to about three gigabytes per hour when streaming an HD movie or other video. However, we did observe substantial variance in video conferencing app hourly data consumption based on the specific app and end-user device.

Key Components of the Testing Environment

Much like our prior work on bandwidth usage, the test setup used typical settings and looked at both upstream and downstream data consumption from laptops connected to a cable broadband internet service. We used the same network equipment from November and our more recent blog post in February. This includes the same cable equipment as the previous blogs — the same DOCSIS 3.0 Technicolor TC8305c gateway, supporting eight downstream channels and four upstream channels, and the same CommScope E6000 cable modem termination system (CMTS). The cable network was configured to provide 50 Mbps downstream and five Mbps upstream broadband service, overprovisioned by 25 percent.

The data gathering scenario:

- 10 people, each on their individual laptops, participated in the conference under test

- One person on the broadband connection under test, using either a lower-cost or a higher-cost laptop. The other nine participants were not using the broadband connection under test.

- For the laptop under test, the participant used the video conferencing application for the laptop’s operating system, rather than using the video conferencing application through the web browser.

- Total data consumption was recorded for the laptop using the broadband connection under test.

For all 10 participants, cameras and microphones were on. Conference applications were set to "gallery mode" with thumbnails of each person filling the screen, no slides were presented and the video conference sessions just included people talking.

The laptop under test used a wired connection to the cable modem to ensure that no variables outside the control of the service provider would impact broadband performance. Most notably, by using a wired connection, we removed the variable of Wi-Fi performance from our test setup. During data collection, the conference app was the only app open on the laptop under test.

Video conferencing sessions were set up and data consumption was measured over time. We collected 10 minutes of data for each conferencing session under test to calculate the total consumption for one hour. The charts below show the data consumed for each of the 10 minutes of the conference session. During the conference there was movement and discussion to keep the video and audio streams active throughout the period of data collection.

For each test scenario, only one laptop was connected at a time to the broadband connection under test. Our goal was to measure the data consumption of one conferencing user on the broadband connection. The other conference participants were on the internet; they were not in the lab. Once again, we used TShark (a popular, widely used network protocol analyzer) to capture and measure the data.

For the laptop under test, we chose two that have quite different capabilities. The first was a low-cost laptop with an 11-inch screen, like the ones students are often provided by school districts for at-home learning. The second was a higher-cost laptop with a 15-inch screen, like what we often see in an enterprise environment. Note the two laptops not only have quite different hardware components (e.g., CPU, graphics processors, memory, cameras, screens), but also have different operating systems. Once again, to avoid any appearance of endorsement, we are not identifying the specific laptops used.

Analysis

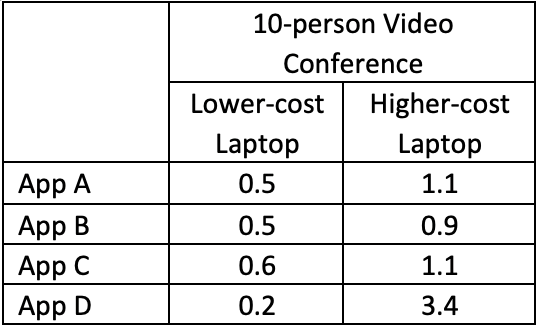

Table 1 shows hourly bandwidth consumption (combining both upstream and downstream) for the laptop under test, normalized to Gigabytes per hour. The table provides the data consumption for the low-cost and higher-cost laptops in each scenario with the four conferencing applications.

Table 1: Video Conferencing App Hourly Bandwidth Consumption in Gigabytes for Each User (Gigabytes/hour)

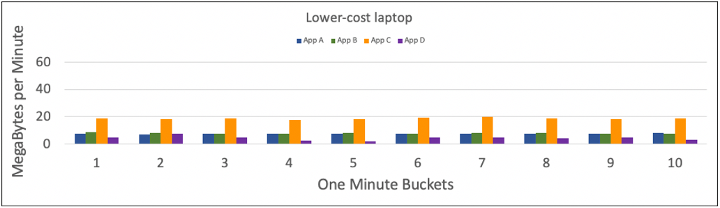

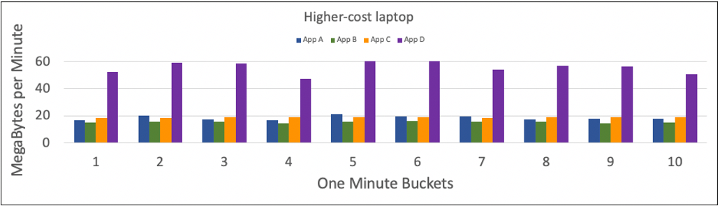

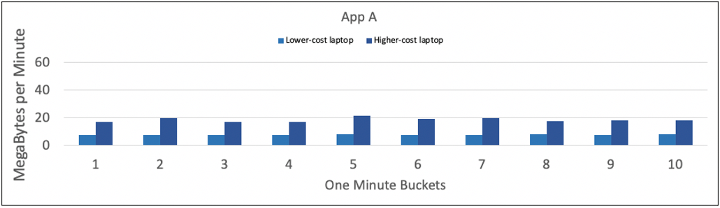

The following figures show the data consumption, in Megabytes, for each minute of the 10-minute data collection for each of the permutations of our testing.

A few notes on the charts:

- There was only one client behind the cable modem.

- Each bar represents one minute of data consumption.

- Each bar shows total consumption and includes both the upstream and downstream, and both audio and video, added together.

- App A is blue in each chart; App B is green; App C orange; and App D is purple.

- These charts show real-time consumption measured in Megabytes per hour to illustrate consumption over time.

Figure 1 shows the data consumed when using the lower-cost laptop in the 10-person meetings.

Figure 2 shows data consumed each minute for each of the four apps when using the higher-cost laptop was in the 10-person meetings.

Figure 3 shows the data consumed each minute using App A and compares the two laptops used for data collection. For each minute, the bar to the left is the lower-cost laptop and the bar to the right is the higher-cost laptop.

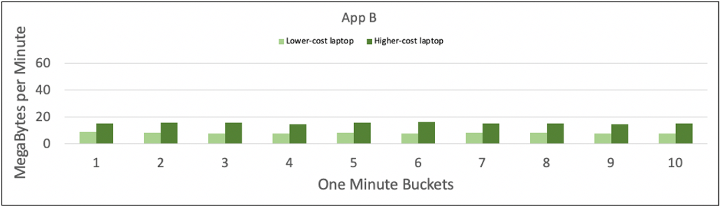

Figure 4 shows the data consumed each minute using App B and compares the two laptops. The bar to the left is the lower-cost laptop and the bar to the right is the higher-cost laptop.

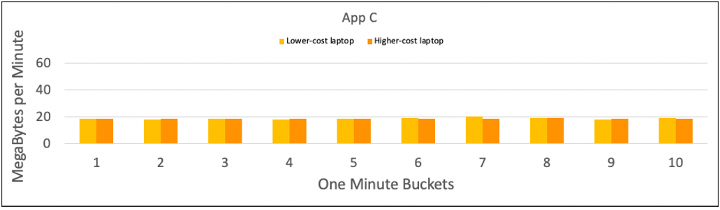

Figure 5 shows the data consumed each minute using App C and compares the two laptops. The bar to the left is the lower-cost laptop and the bar to the right is the higher-cost laptop.

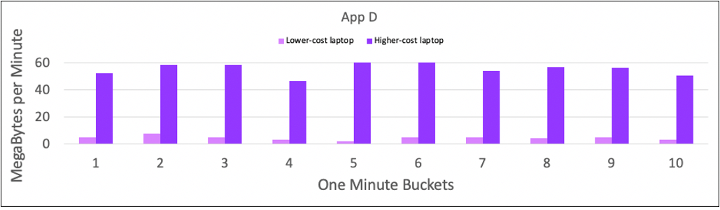

Figure 6 shows the data consumed each minute using App D and compares the two laptops. The bar to the left is the lower-cost laptop and the bar to the right is the higher-cost laptop.

Key Observations

A. Data Consumption Varies: The first takeaway is that different apps consume different amounts of bandwidth, as shown in Table 1, from 0.5 GBytes per hour up to 3.4 GBytes per hour, for video conferences using the different laptops, the same broadband connections, the same general setup (e.g., gallery view), the same people doing the same things on camera, etc.

-

- For a given app on a given laptop, data consumption was consistent over the 10-minute collection time.

- App D using the higher-cost laptop consumed the most bandwidth.

- With App D on the lower-cost laptop, there was video quality degradation. We confirmed the broadband connection was operating as expected and was not the cause of the video degradation. Rather, it appeared that the combination of the hardware and operating system of the lower-cost laptop was unable to meet the resource requirements of App D.

- App B consistently consumed less bandwidth regardless of scenario.

B. Comparing Laptops: In Table 1, the two columns of data show the differences between the lower-cost and higher-cost laptops for the data collections. On the lower-cost laptop, Apps A, B and C consume about the same amount of data on an hourly basis.

C. Comparing Laptops: The second column of data show that all apps on the higher-cost laptop consumed more bandwidth than the lower-cost laptop. This difference implies that when using the actual conferencing app (not a web browser), processing power available in the laptop may be a determining factor in consumption.

D. Comparing Apps: App C was the most consistent in data consumption regardless of the laptop used. The other conference applications noticeably consumed more on the higher-cost laptop.

In summary, we observed a more than 7X variation in the data consumption of video conferencing with a very limited exploration of just two variables – laptop and video conferencing application. Notably, however, when data consumption was at its highest, it was of the same magnitude as the data consumption of an HD video stream.

This is an area ripe for further research and study, both to more comprehensively explore these variables (e.g., other device types, larger meetings) and to explore other variables that may meaningfully influence data consumption.

HFC Network

Expanded Testing of Video Conferencing Bandwidth Usage Over 50/5 Mbps Broadband Service

As working from home and remote schooling remain the norm for most of us, we wanted to build on and extend our prior investigation of the bandwidth usage of popular video conferencing applications. In this post, we examine the use of video conferencing applications over a broadband service of 50 Mbps downstream and 5 Mbps upstream (“50/5 broadband service”). The goal remains the same, looking at how many simultaneous conferencing sessions can be supported on the access network using popular video conferencing applications. As before, we examined Google Meet, GoToMeeting, and Zoom, and this time we added Microsoft Teams and an examination of a mix of these applications. To avoid any appearance of endorsement of a particular conferencing application, we haven’t labeled the figures below with the specific apps under test.

We used the same network equipment from November. This includes the same cable equipment as the previous blog -- the same DOCSIS 3.0 Technicolor TC8305c gateway, supporting 8 downstream channels and 4 upstream channels, and the same CommScope E6000 cable modem termination system (CMTS).

The same laptops were also used, though this time we increased it to 10 laptops. Various laptops were used, running Windows, MacOS and Ubuntu – nothing special, just laptops that were around the lab and available for use. All used wired Ethernet connections through a switch to the modem to ensure no variables outside the control of the broadband provider would impact the speeds delivered (e.g., placement of the Wi-Fi access point, as noted below). Conference sessions were set up and parameters varied while traffic flow rates were collected over time. Throughout testing, we ensured there was active movement in view of each laptop’s camera to more fully simulate real-world use cases.

As in the previous blog, this research doesn’t take into account the potential external factors that can affect Internet performance in a real home -- from the use of Wi-Fi, to building materials, to Wi-Fi interference, to the age and condition of the user’s connected devices -- but it does provide a helpful illustration of the baseline capabilities of a 50/5 broadband service.

As before, the broadband speeds were over-provisioned. For this testing, the 50/5 broadband service was over provisioned by 25%, a typical configuration for this service tier.

First things first: We repeated the work from November using the 25/3 broadband service. And happily, those results were re-confirmed. We felt the baseline was important to verify the setup.

Next, we moved to the 50/5 broadband service and got to work. At a high level, we found that all four conferencing solutions could support at least 10 concurrent sessions on 10 separate laptops connected to the same cable modem with the aforementioned 50/5 broadband service and with all sessions in gallery view. The quality of all 10 sessions was good and consistent throughout, with no jitter, choppiness, artifacts or other defects noticed during the sessions. Not surprisingly, with the increase in the nominal upstream speed from 3 Mbps to 5 Mbps, we were able to increase the number of concurrent sessions from the 5 we listed in the November blog to 10 sessions with the 50/5 broadband service under test.

The data presented below represents samples that were collected every 200 milliseconds over a 5-minute interval (300 seconds) using tshark (the Wireshark network analyzer).

Conferencing Application: A

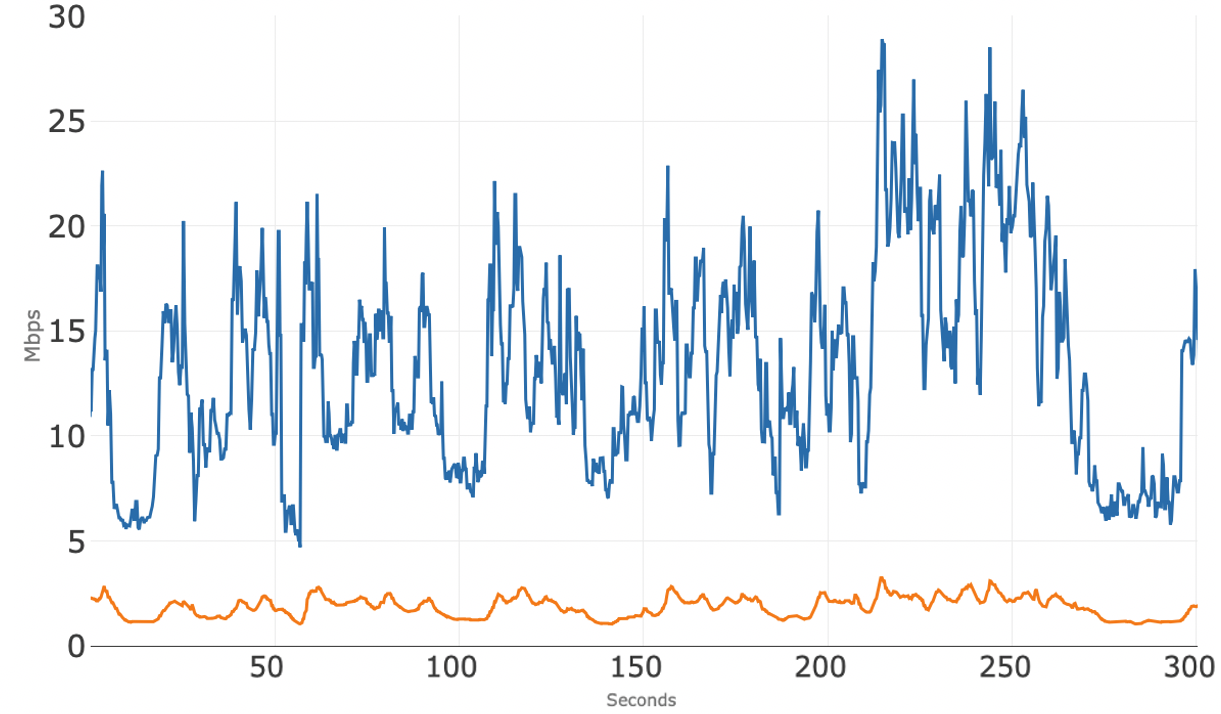

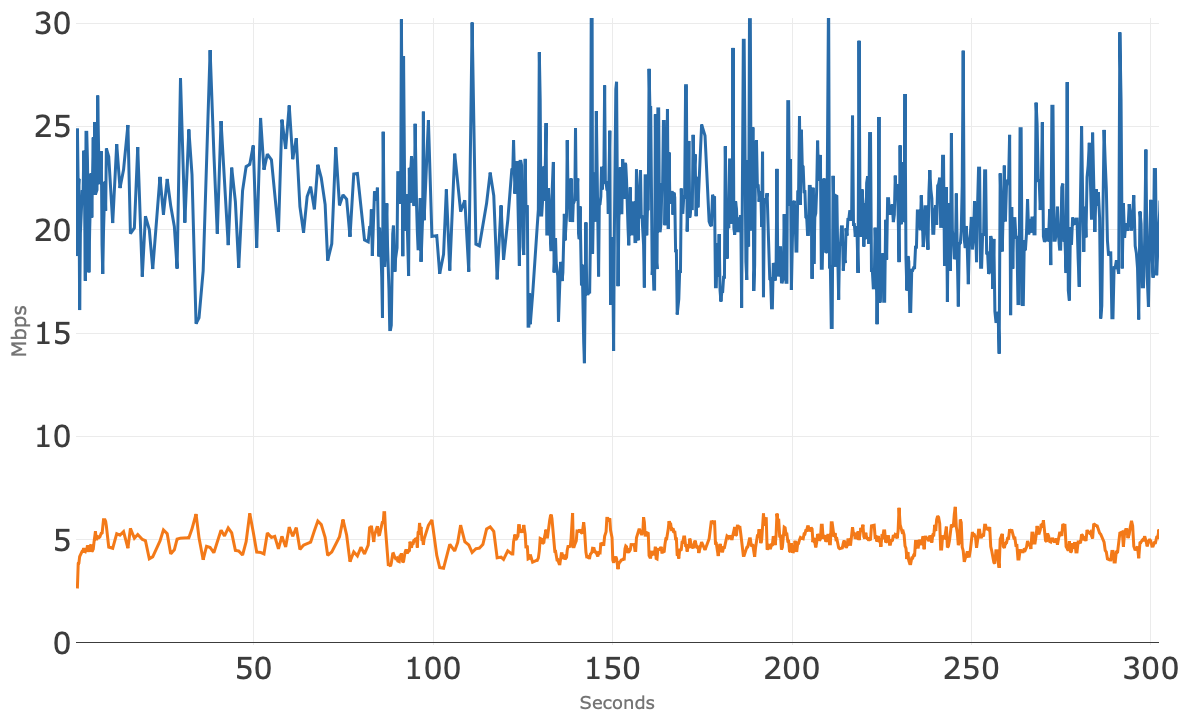

The chart below (Figure 1) shows total access network usage for the 10 concurrent sessions over 300 seconds (5 minutes) while using one of the above conferencing applications. The blue line is the total downstream usage, and the orange line is total upstream usage. Note that the total upstream usage stays around 2.5 Mbps which may be a result of running 10 concurrent sessions. Also, the downstream usage stays, on average, around 15 mbps, which leaves roughly 35 Mbps of downstream headroom for other services such as streaming video that can also use the broadband connection at the same time.

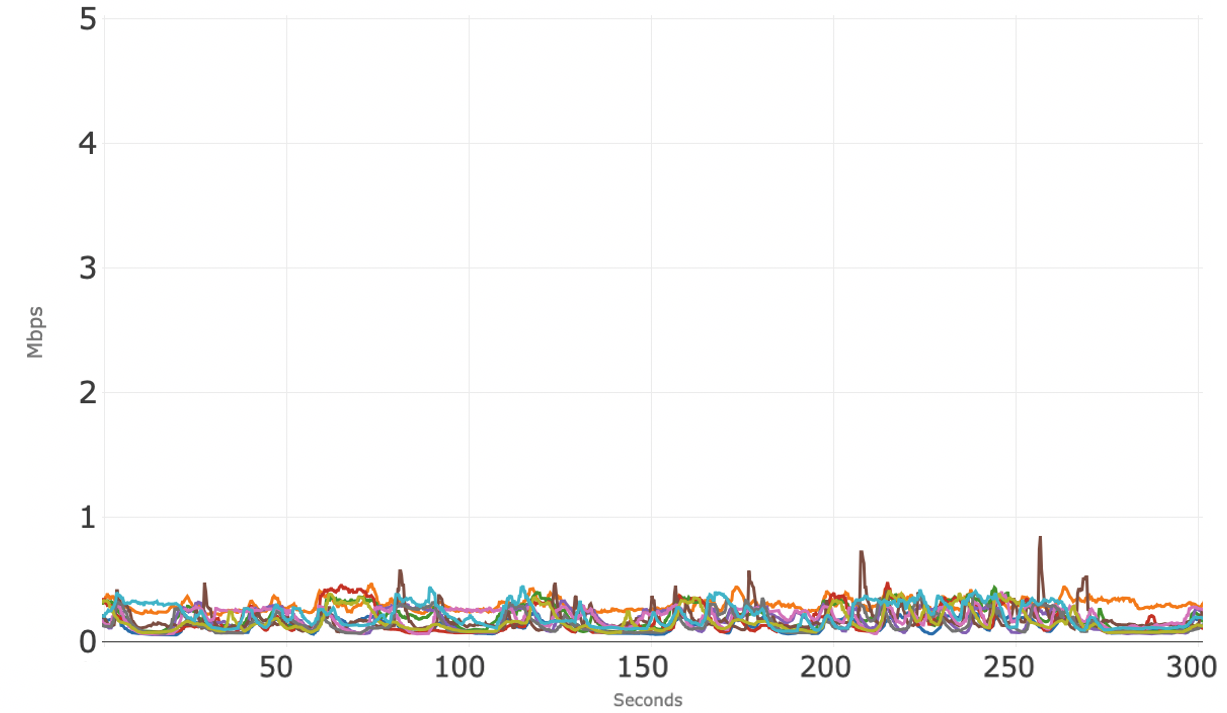

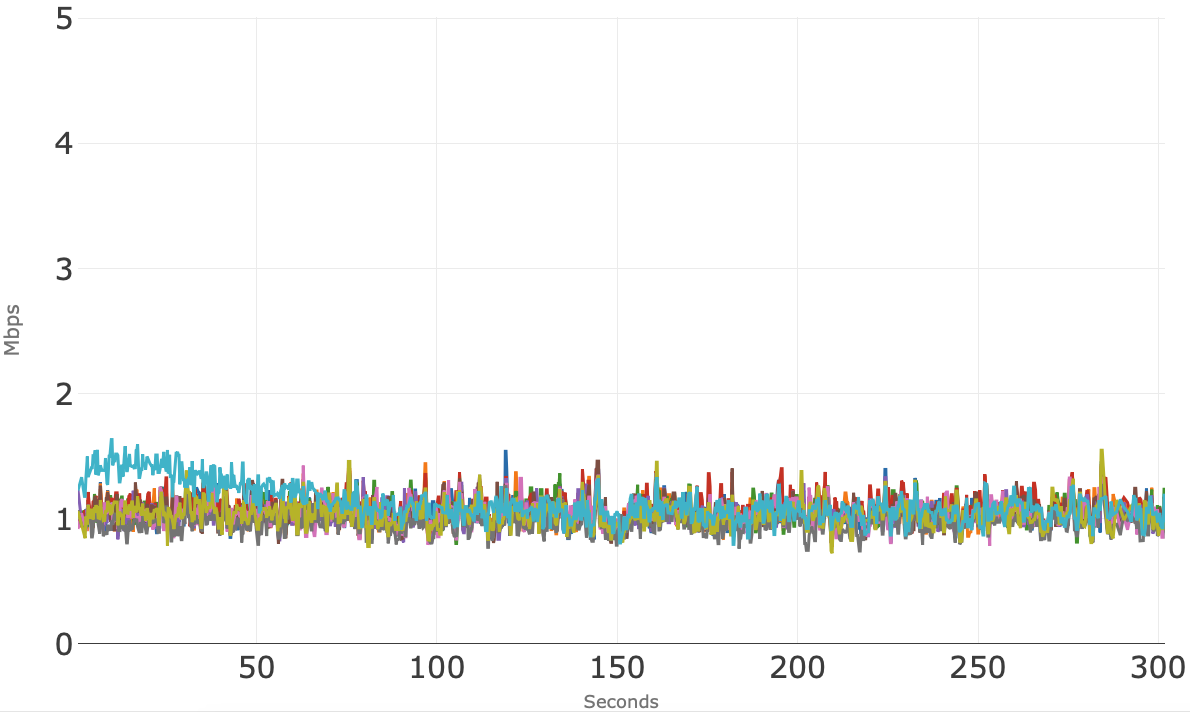

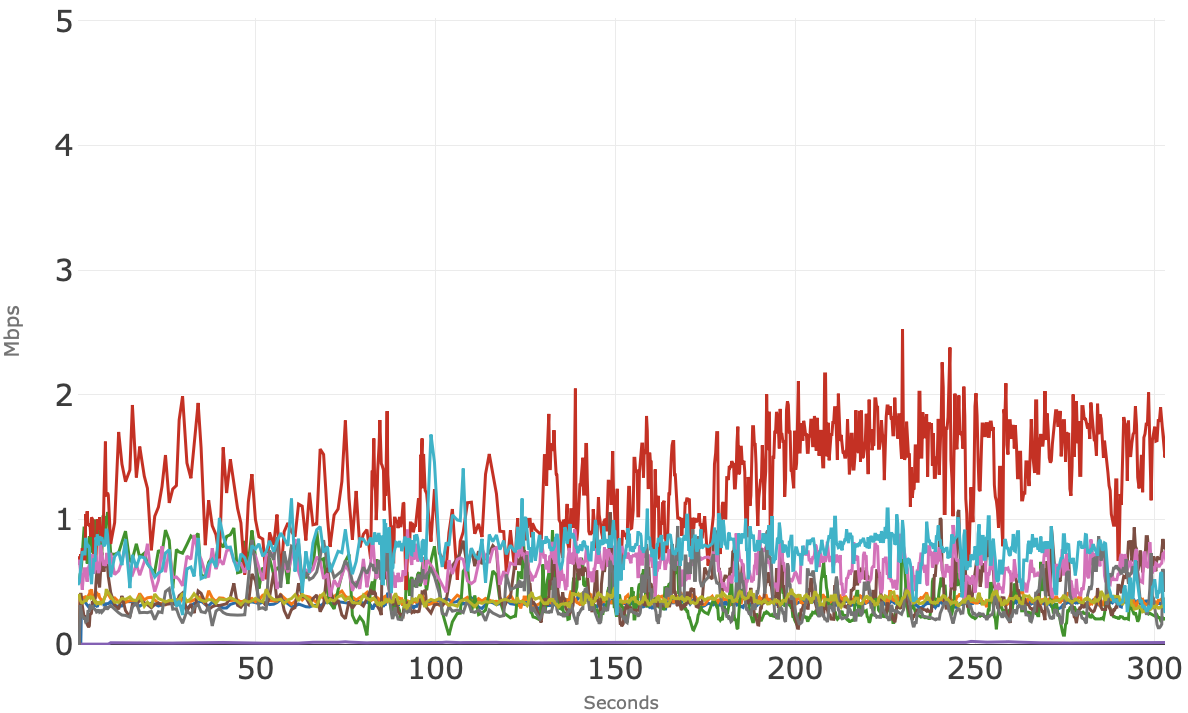

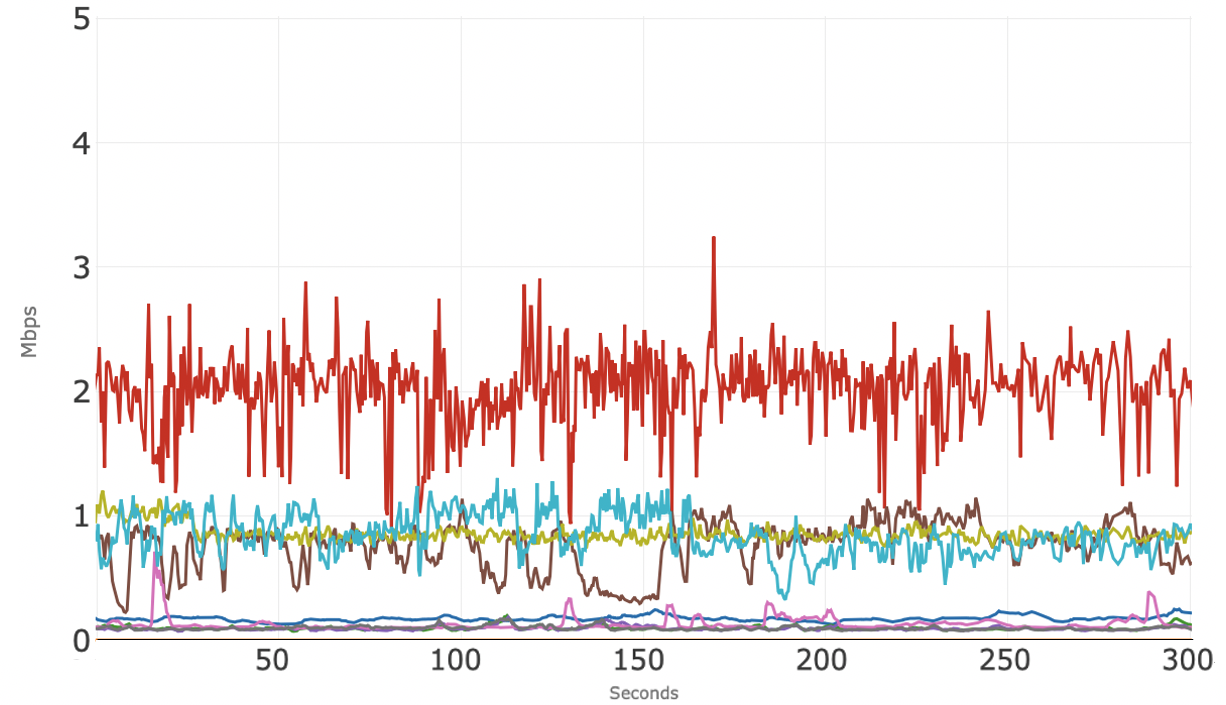

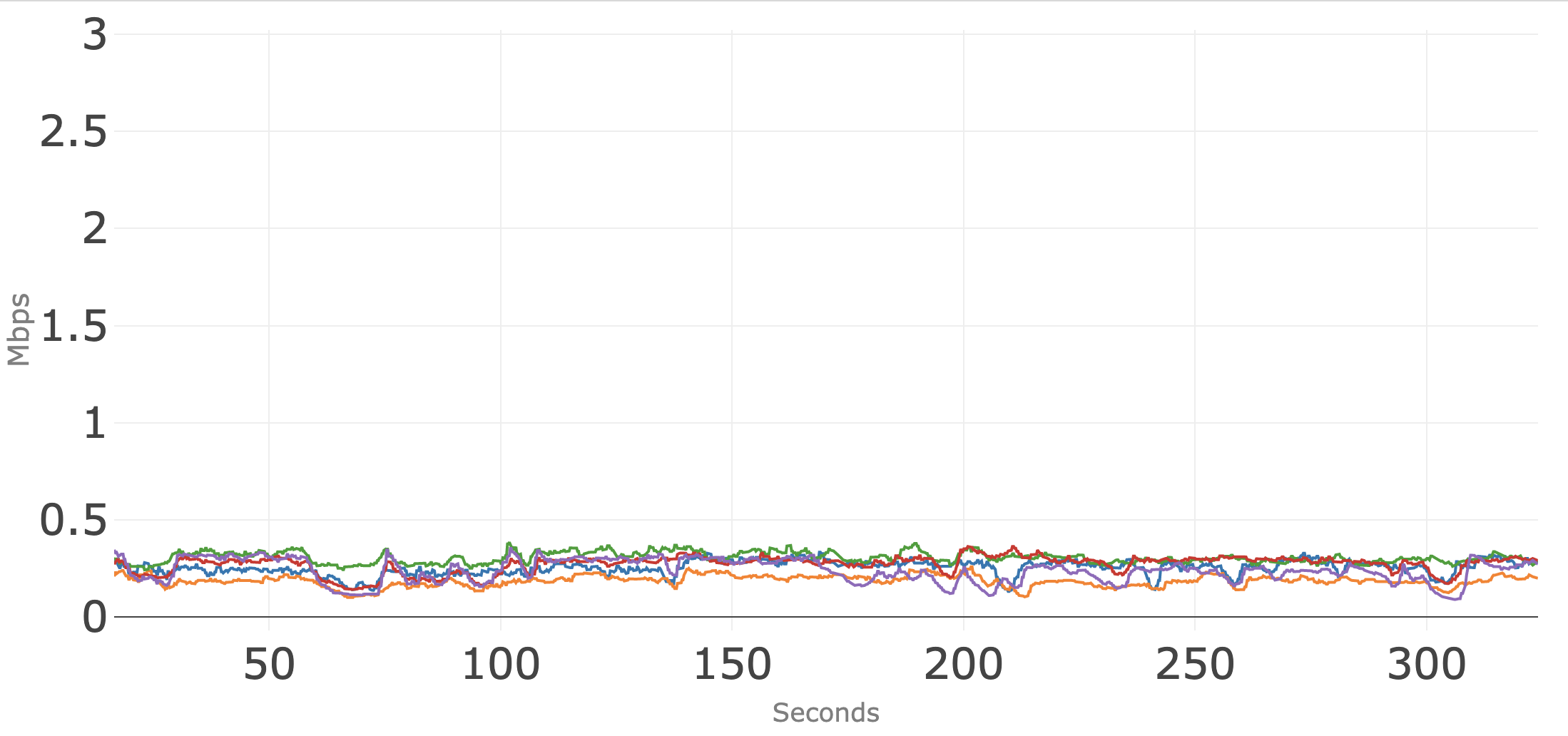

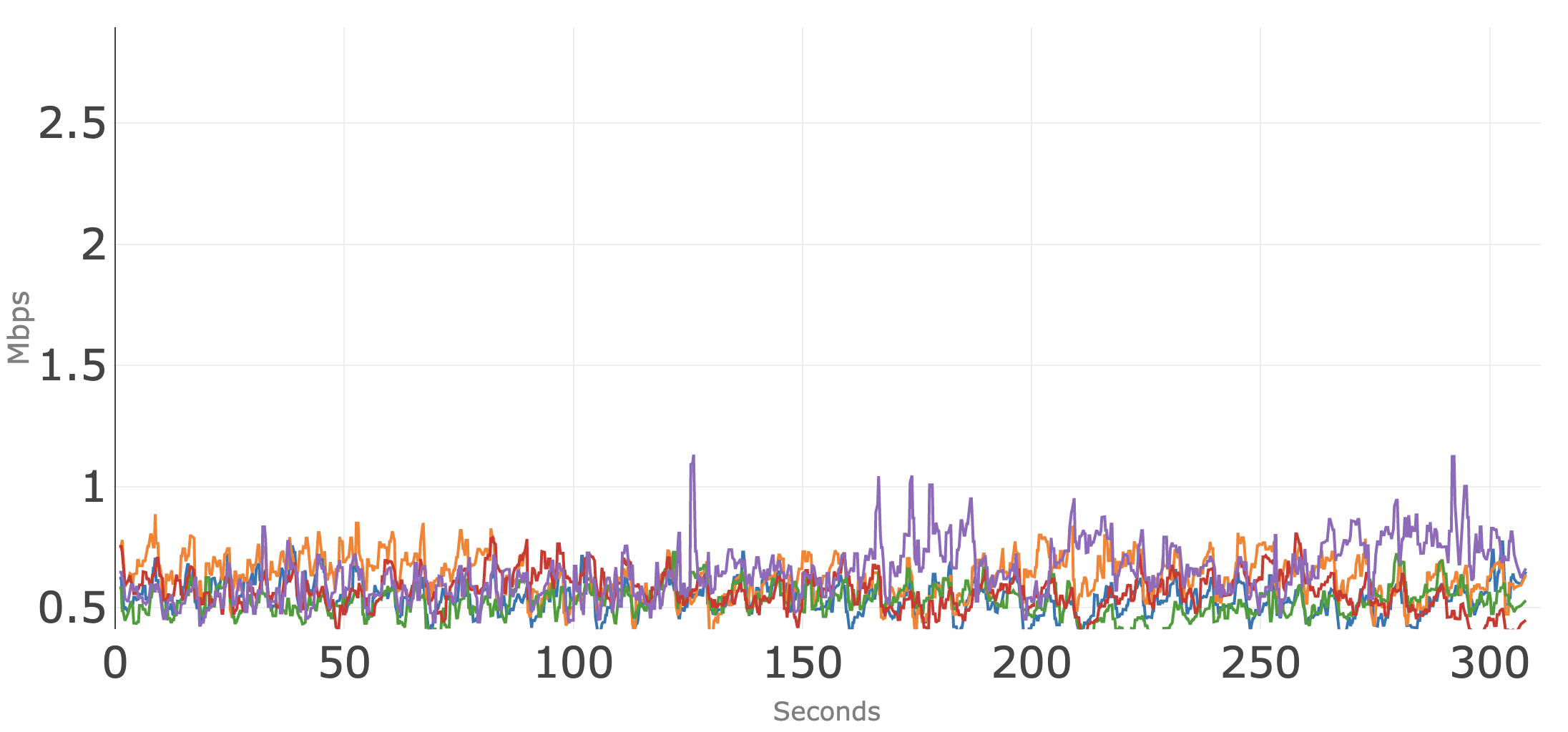

Figure 2 shows the upstream bandwidth usage of the 10 concurrent sessions and it appears that these individual sessions are competing amongst themselves for upstream bandwidth. However, all upstream sessions typically stay well below 0.5 Mbps -- these streams are all independent, with the amount of upstream bandwidth usage fluctuating over time.

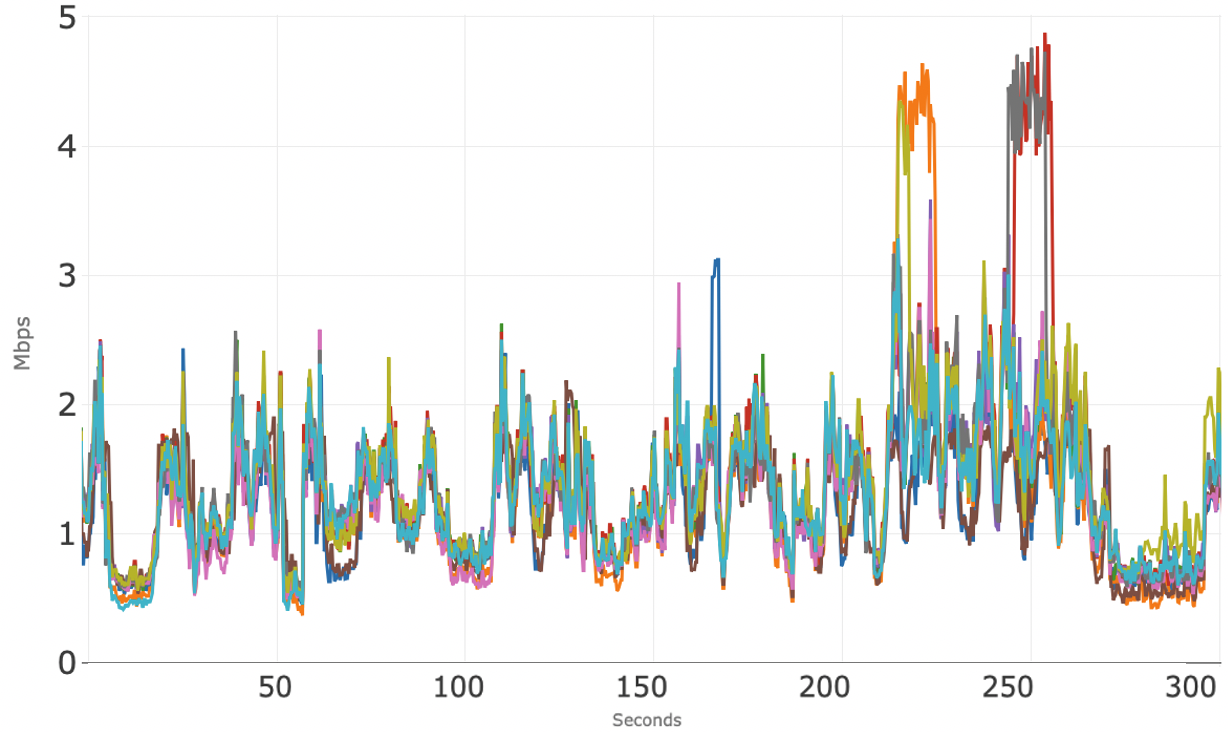

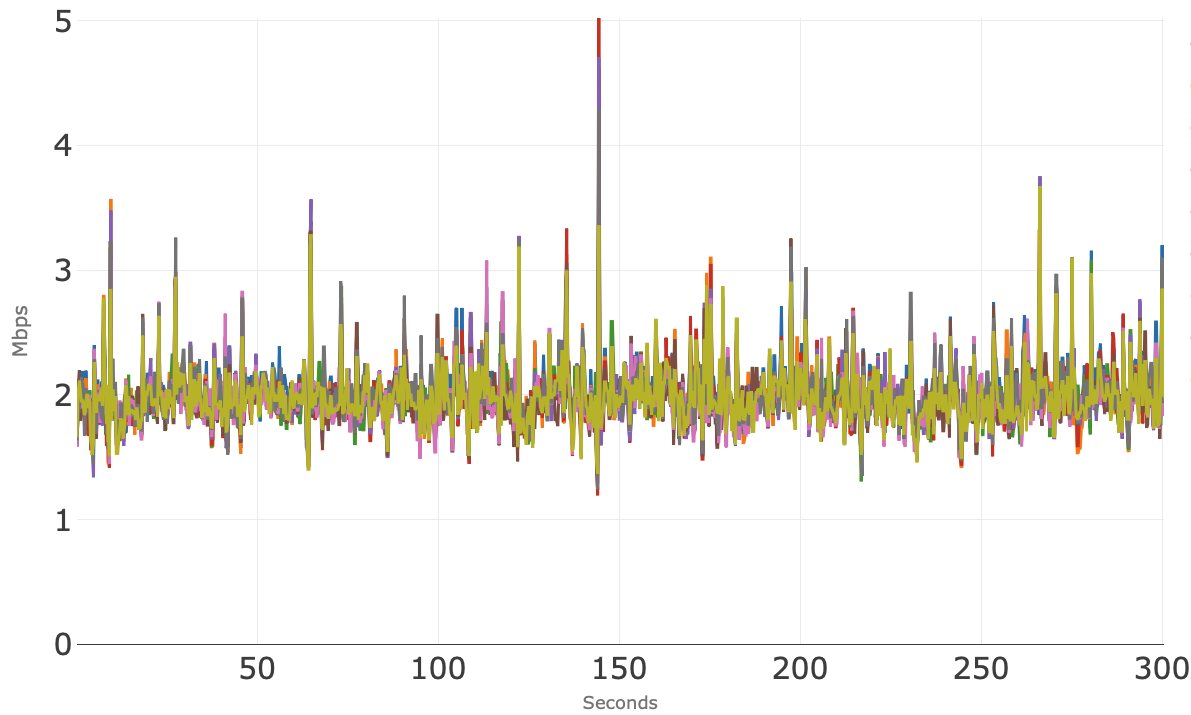

Figure 3 shows the downstream bandwidth usage for the 10 individual conference sessions. Each conference session typically uses between 1 to 2 Mbps. As previously observed with this application, there are short periods of time when some of the sessions use more downstream bandwidth than the typical 1 to 2 Mbps.

Conferencing Application: B

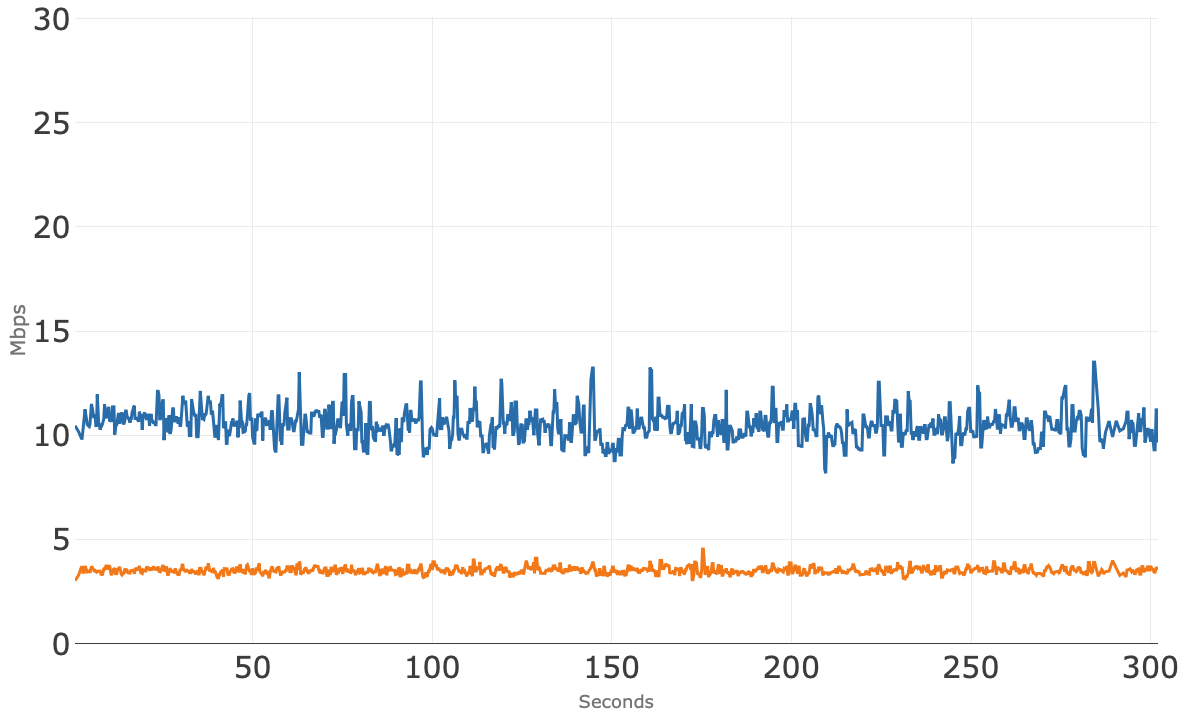

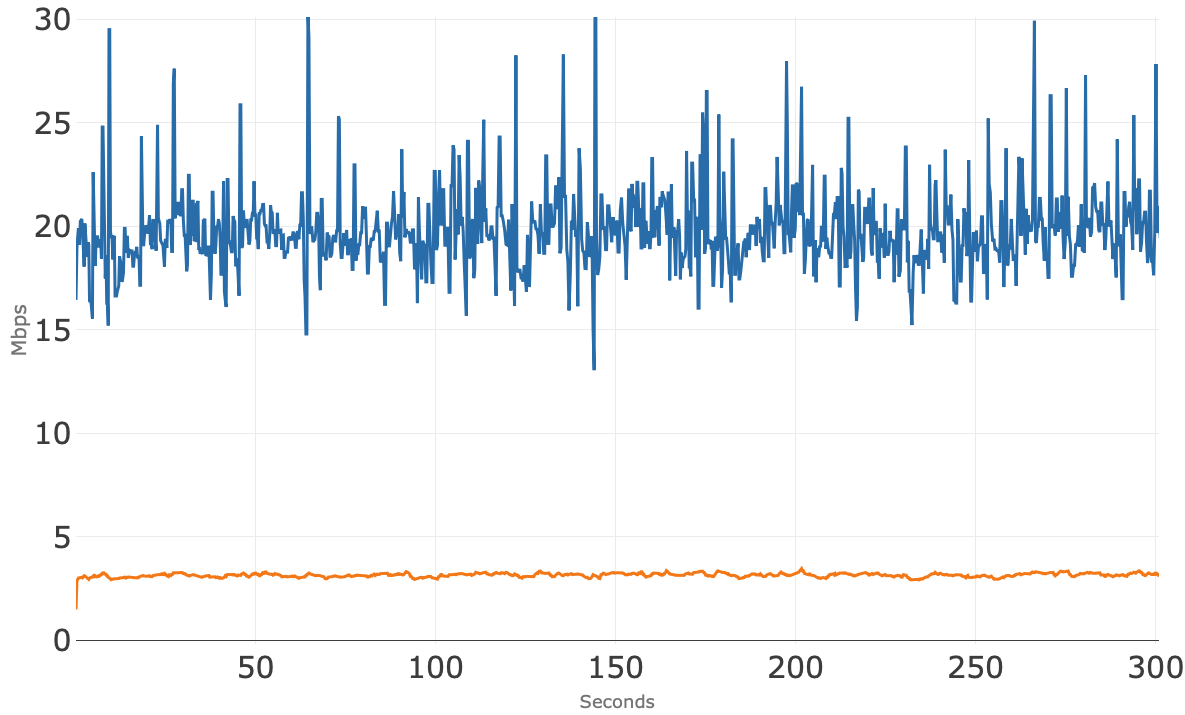

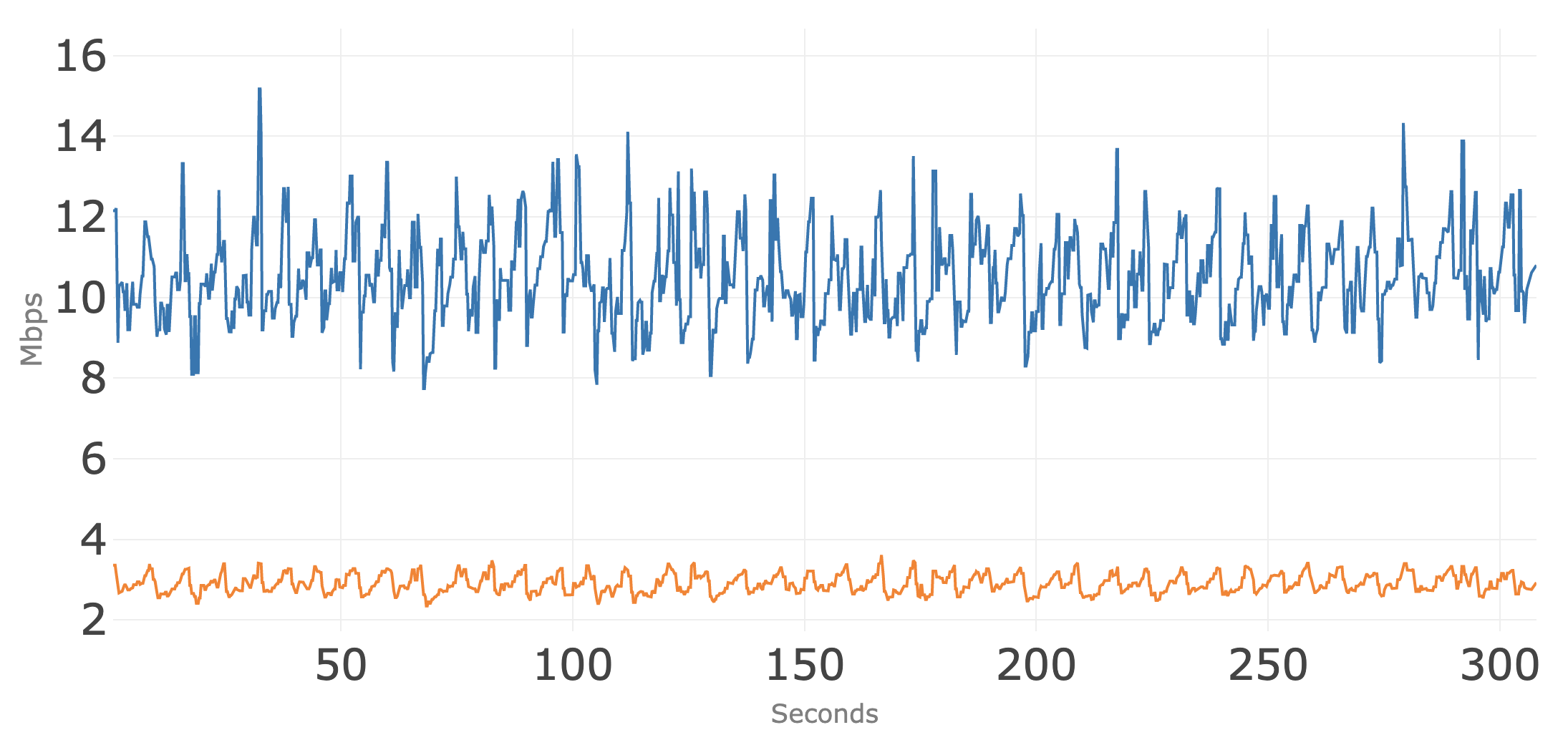

Figure 4 shows access network usage for 10 concurrent sessions over 300 seconds (5 minutes) for the second conferencing application tested. The blue line is the total downstream usage, and the orange line is total upstream usage. Note that the total upstream usage hovers around 3.5 Mbps. The total downstream usage is very tight, right above 10 Mbps.

Figure 5 shows the upstream bandwidth usage of the 10 individual conference sessions where all but one session is well below 1 Mbps and that one session is right at 2 Mbps. We don’t have an explanation for why that blue session is so much higher than the others, but it falls well within the available upstream bandwidth.

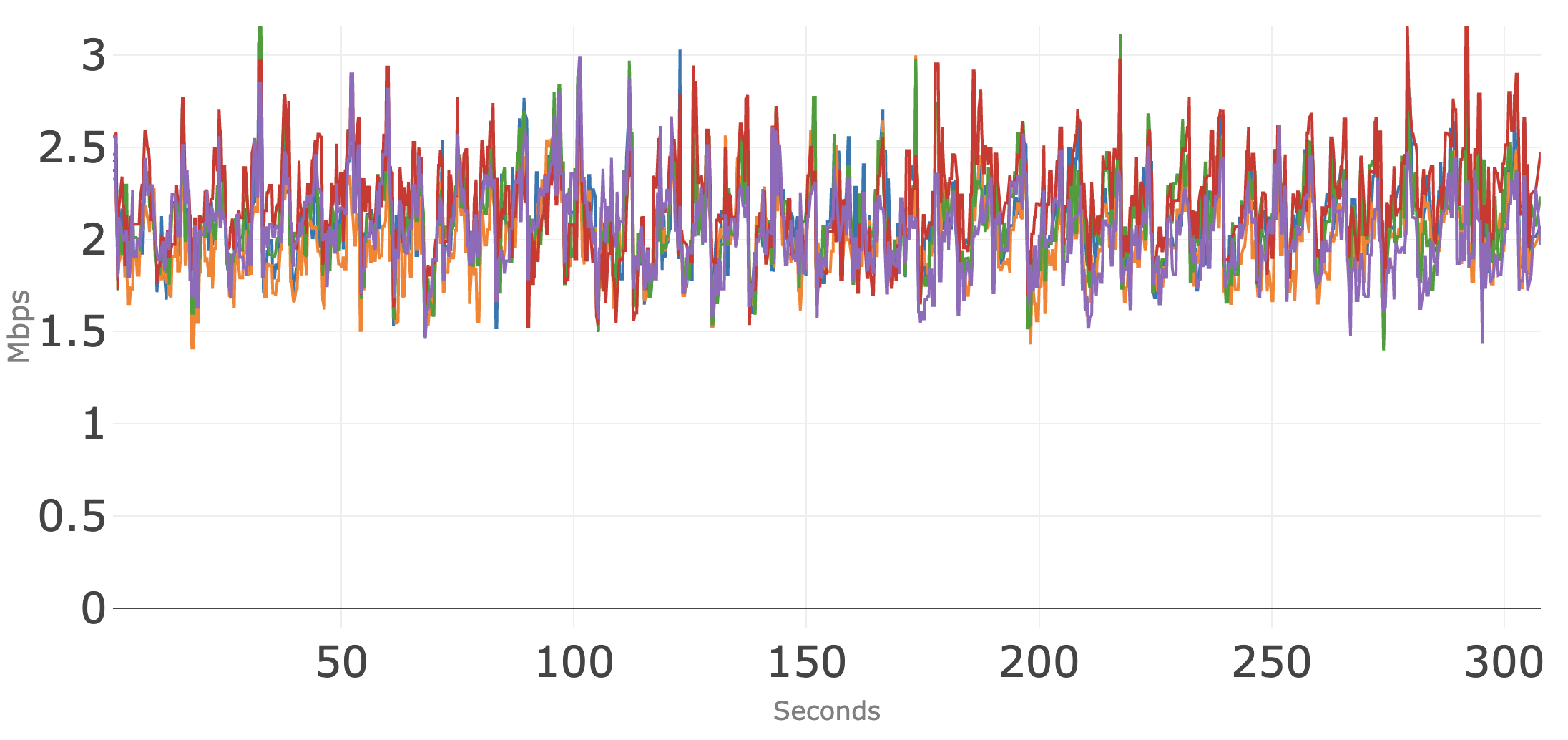

Figure 6 shows the downstream bandwidth usage for the 10 individual conference sessions clusters consistently around 1 Mbps.

Conferencing Application: C

Figure 7 shows access network usage for the 10 concurrent sessions over 300 seconds (5 minutes) for the third application tested. The blue line is the total downstream usage, and the orange line is total upstream usage. Note that the total upstream usage hovers right at 3 Mbps over the 5 minutes.

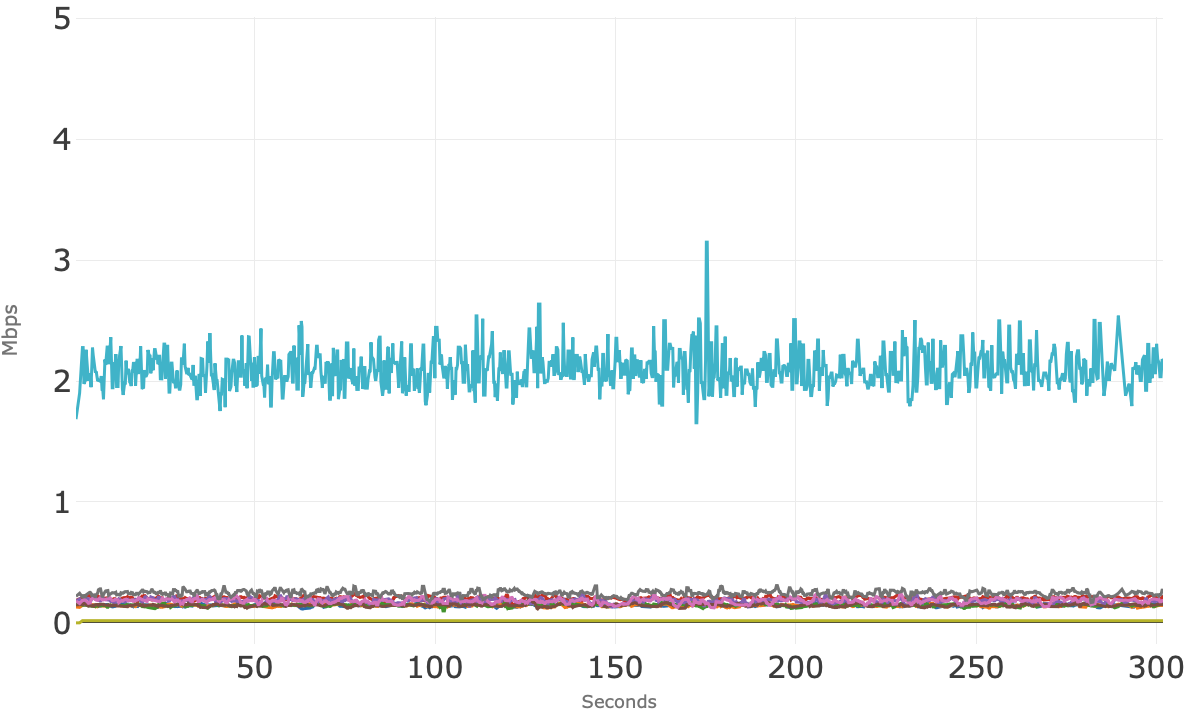

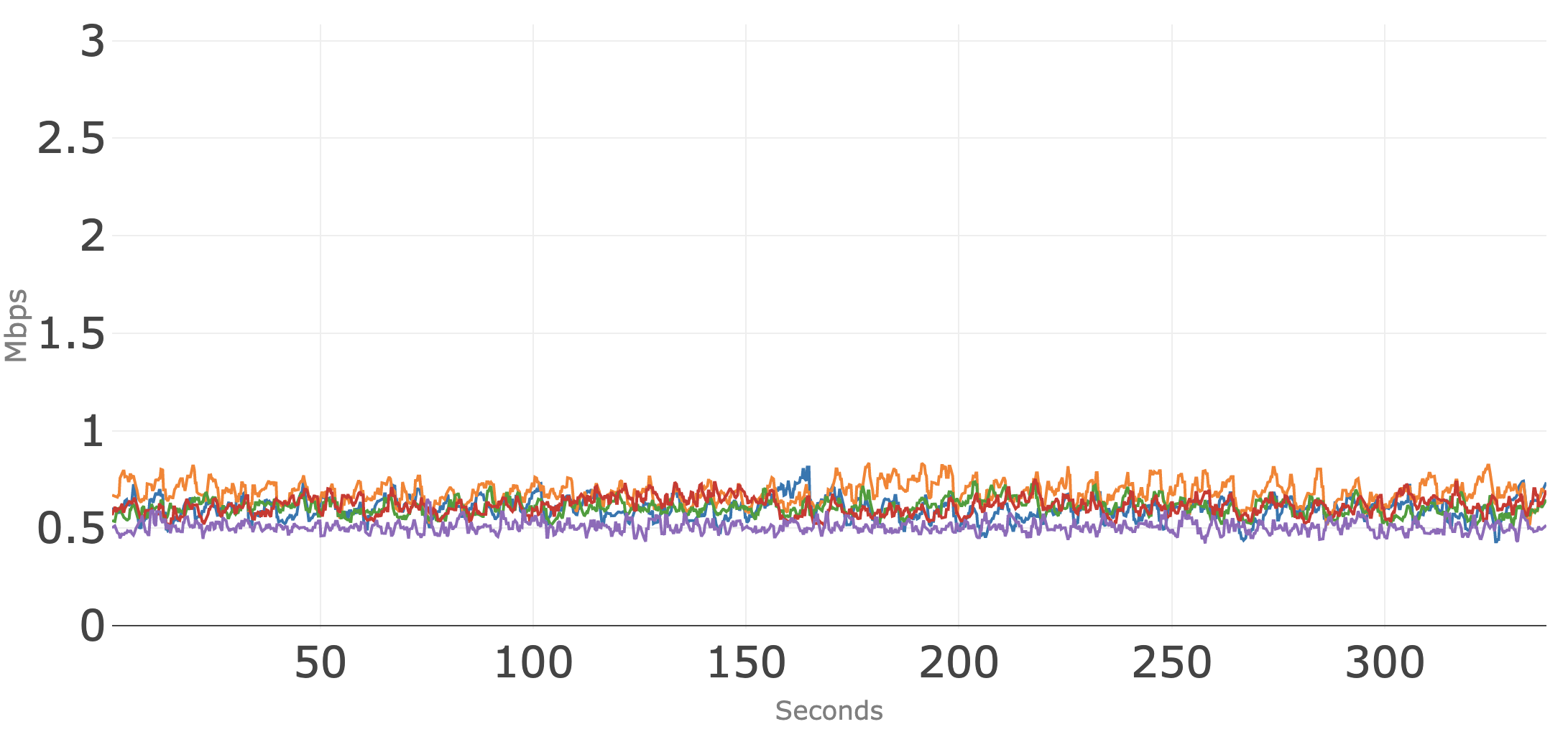

Figure 8 shows the upstream bandwidth usage of the 10 individual conference sessions where all stay well below 1 Mbps.

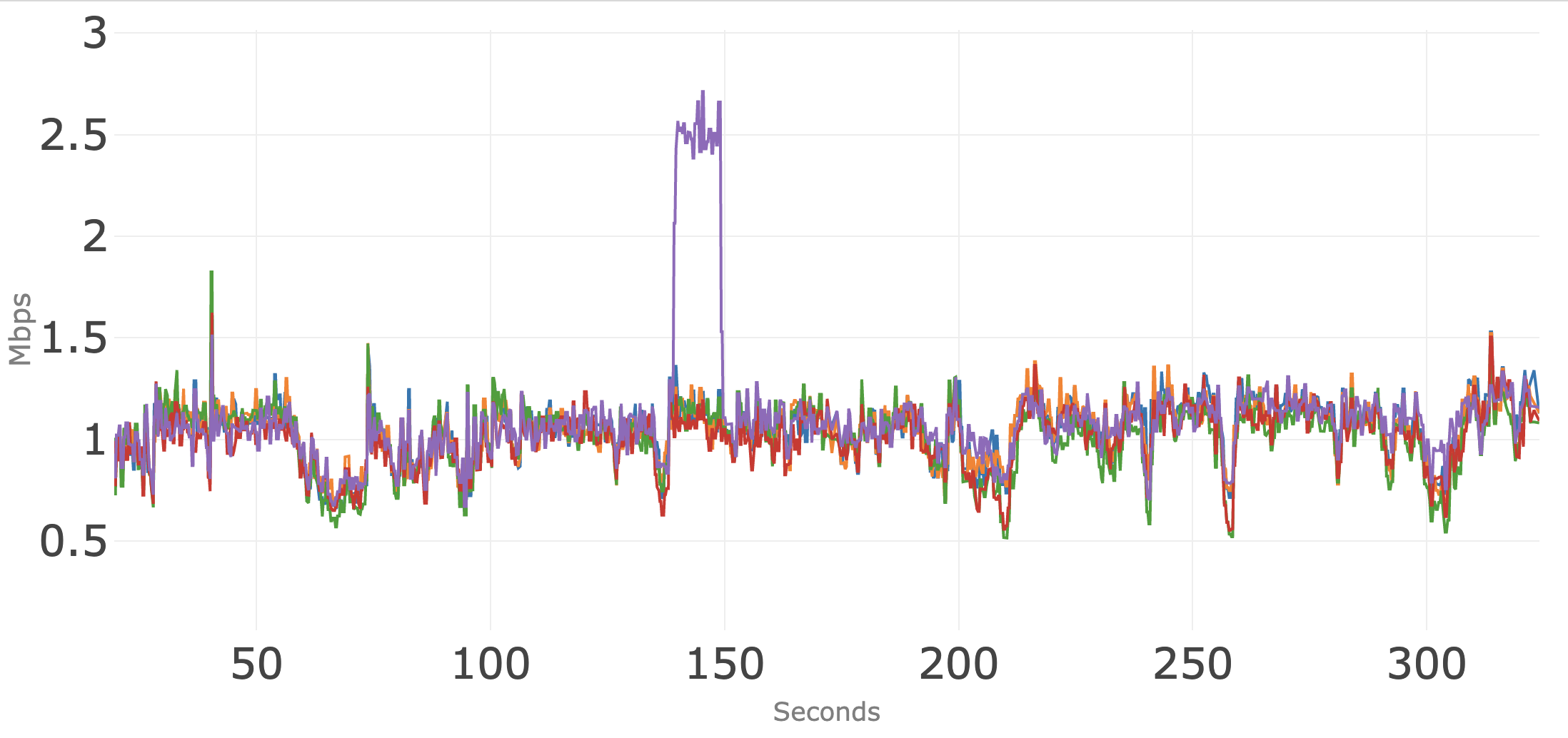

Figure 9 shows the downstream bandwidth usage for the 10 individual conference sessions. These sessions appear to track each other very closely around 2 Mbps, which matches Figure 7 showing aggregate downstream usage around 20 Mbps.

Conference Application: D

Figure 10 shows access network usage for the 10 concurrent sessions over 300 seconds (5 minutes) for the fourth application tested. The blue line is the total downstream usage, and the orange line is total upstream usage. Note that the total upstream usage hovers right at 5 Mbps over the 5 minutes, and there is no visible degradation to the conferencing sessions was observed.

Figure 11 shows the upstream bandwidth usage of the 10 individual conference sessions, where there is some variability in bandwidth consumed per session. One session (red) consistently uses more upstream bandwidth than the other sessions but remained well below the available upstream bandwidth.

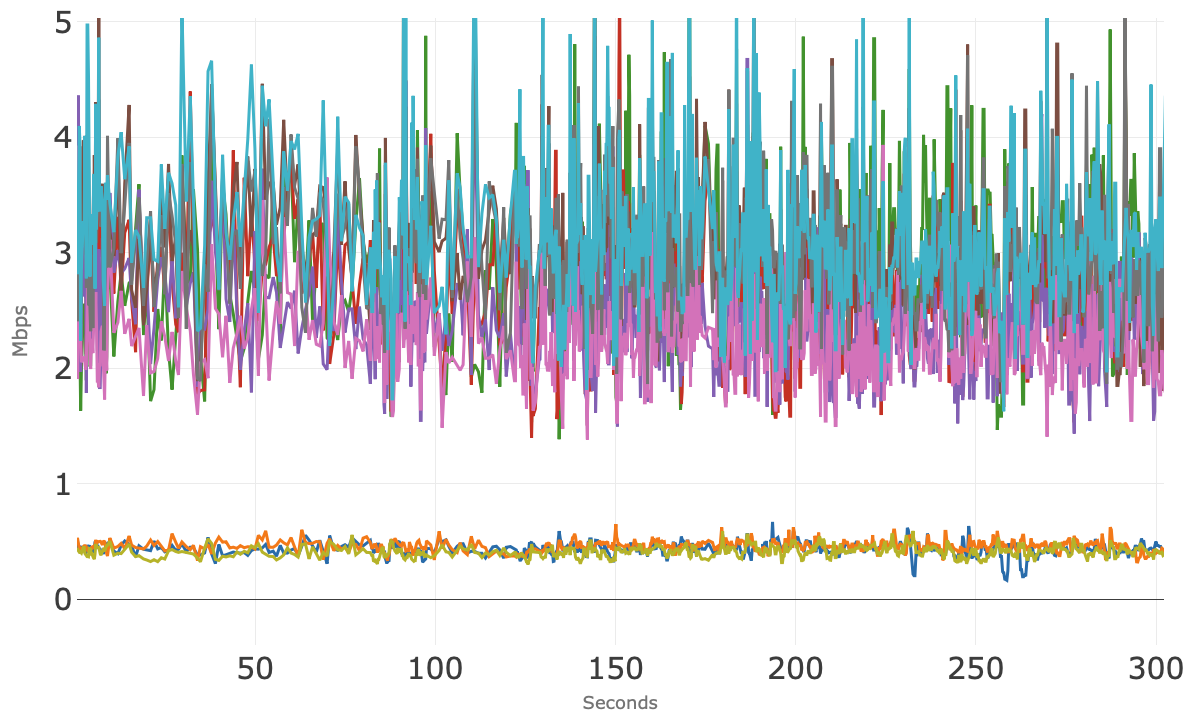

Figure 12 shows the downstream bandwidth usage for the 10 individual conference sessions. These sessions show two groups, with one group using less than 1 Mbps of bandwidth and the second group using consistently between 2 Mbps and 4 Mbps of bandwidth.

Running All Four Conference Applications Simultaneously

In this section, we examine the bandwidth usage of all four conferencing applications running simultaneously. The test consists of three concurrent sessions from two of the applications and two concurrent sessions from the other two applications (once again a total of 10 conference sessions running simultaneously). The goal is to observe how the applications may interact in the scenario where members of the same household are using different conference applications at the same time.

Figure 13 shows access network usage for these 10 concurrent sessions over 300 seconds (5 minutes). The blue line is the total downstream usage, and the orange line is total upstream usage. Note that the total upstream usage once again hovers around 5 Mbps without any visible degradation to the conferencing sessions, and the downstream usage is pretty tight right above 10 Mbps.

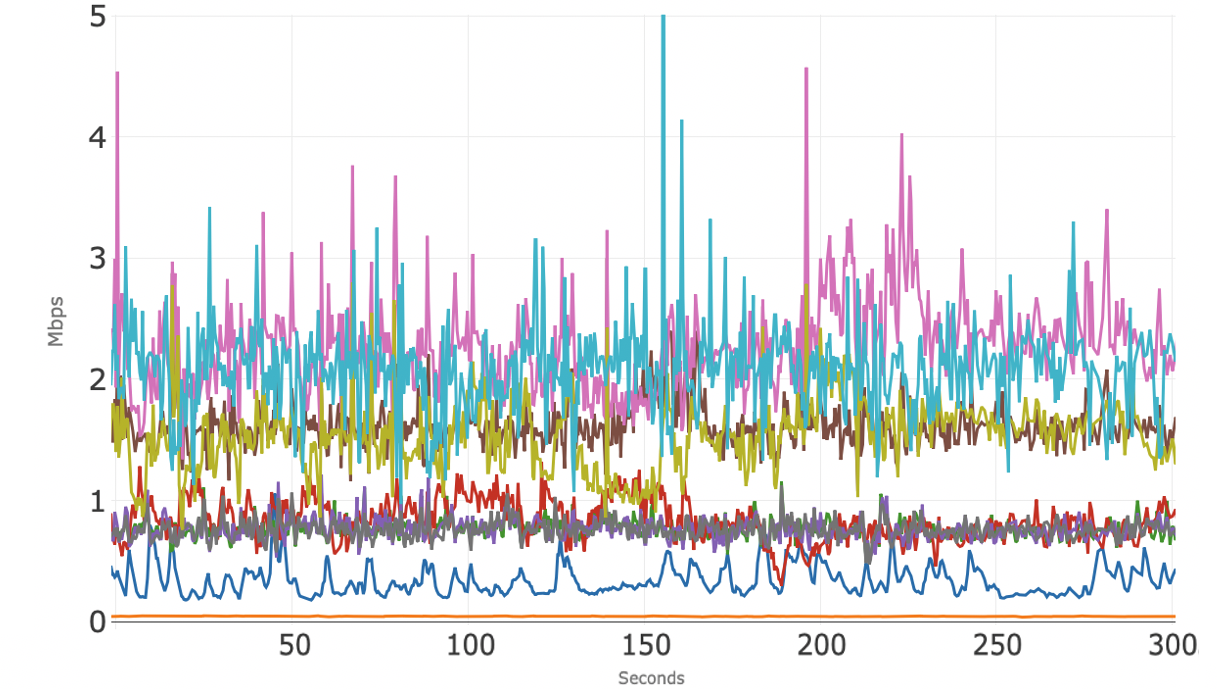

Figure 14 shows the upstream bandwidth usage of the 10 individual conference sessions where several distinct groupings of sessions are visible. There were 4 different apps running concurrently. One session (red) consumes the most upstream bandwidth at averaging around 2 Mbps, whereas the other sessions use less, and some much less.

Figure 15 shows the downstream bandwidth usage for the 10 individual conference sessions across the four apps and, again, there are different clusters of sessions. Each of the four apps are following their own algorithms.

In summary, with a 50/5 broadband service, each of the video-conferencing applications supported at least 10 concurrent sessions, both when using a single conferencing application and when using a mix of these four applications. In all cases, the quality of the 10 concurrent sessions was good and consistent throughout. The 5 Mbps of nominal upstream bandwidth was sufficient to support the conferencing sessions without visible degradation, and there was more than sufficient available downstream bandwidth to run other common applications, such as video streaming and web browsing, concurrently with the 10 conferencing sessions.

HFC Network

Testing Bandwidth Usage of Popular Video Conferencing Applications

This year we have seen a shift toward working and learning from home and relying more on our broadband connection. Specifically, most of us use video conferencing for work, school and everyday communications. With that in mind, we looked at how much video conferencing a broadband connection can support.

In the U.S., the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) defines broadband to be a minimum of 25 Mbps downstream and 3 Mbps upstream. So, we started there. The investigation looked at how many simultaneous conferencing sessions can be supported on the access network using popular software including Google Meet, GoToMeeting, and Zoom. The data gathering used typical settings and looked at both upstream and downstream bandwidth usage from and to laptops connected by ethernet cable to a modem connected to a wired broadband connection. To avoid any appearance of endorsement of a particular conferencing application, we have not labeled the figures below with the specific apps under test.

Since this is CableLabs, we used DOCSIS® cable broadband technology. A Technicolor TC8305c gateway was used, which is a DOCSIS 3.0 modem supporting 8 downstream channels and 4 upstream channels. Note that this modem is several years old and not the current DOCSIS 3.1 technology. The modem was connected through the cable access network to a CommScope E6000 cable modem termination system (CMTS).

Laptops used ethernet wired connections to the modem to ensure no variables outside the control of the service provider would impact the speeds delivered, and conferences were set up and parameters varied while traffic flow rates were collected over time. Various laptops were used, running Windows, MacOS and Ubuntu – nothing special, just laptops that were around the lab and available for use.

Most broadband providers over-provision the broadband speeds delivered to customers’ homes – this is for assorted reasons including considering protocol overhead and ensuring headroom in the system to handle unexpected loads. For this testing, the 25/3 service was over-provisioned by 25%, a typical configuration for this service tier.

At a high level, we found that all three conferencing solutions could support at least five concurrent sessions on five separate laptops connected to the same cable modem with the above 25/3 broadband service and with all sessions in gallery view. The quality of all five sessions was good and consistent throughout, with no jitter, choppiness, artifacts, or other defects noticed during the sessions.

This research doesn’t take into account the potential external factors that can affect Internet performance in the home, from the placement of Wi-Fi routers, to building materials, to Wi-Fi interference, to the age and condition of the user’s connected devices, but it does provide a helpful illustration of the baseline capabilities of 25/3 broadband.

The data is presented below where samples were collected every 200 milliseconds using tshark (the Wireshark network analyzer).

Conferencing Application: A

The chart below (Figure 1) shows access network usage for the five concurrent sessions over 300 seconds (five minutes) for one of the above conferencing applications. The blue line is the total downstream usage, and the orange line is total upstream usage. Note that the upstream usage stays below 2 Mbps over the five minutes.

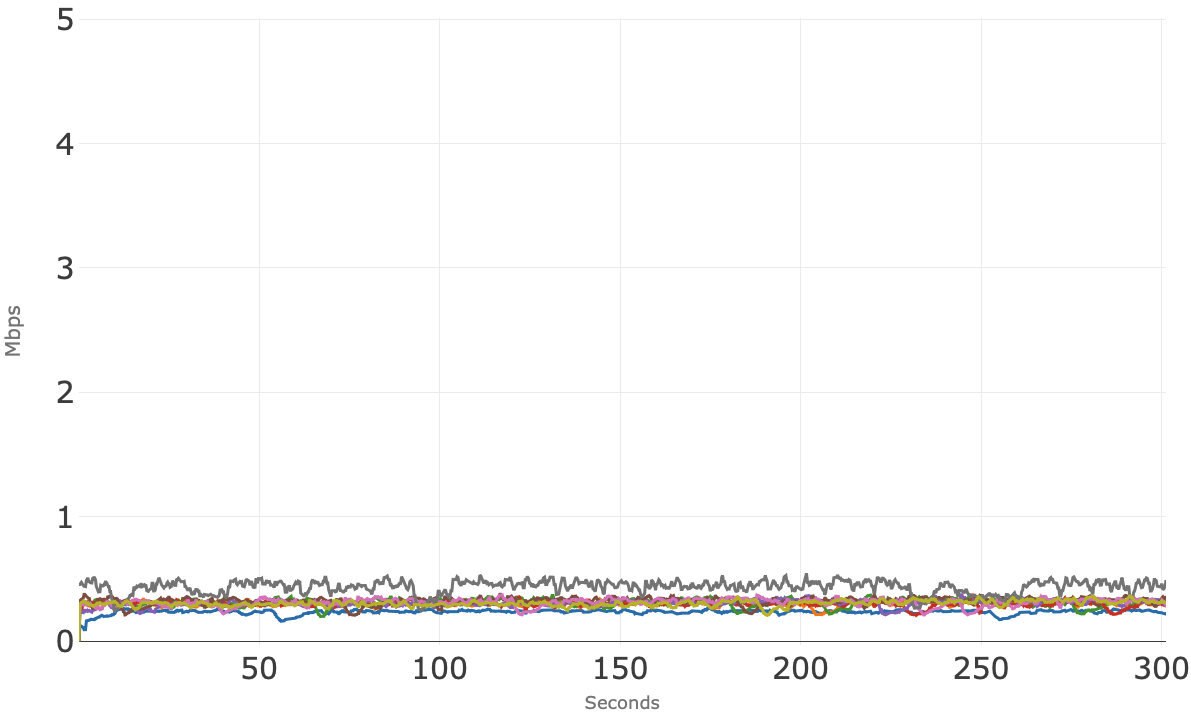

Figure 2 shows the upstream bandwidth usage of the five individual conference sessions where each is below 0.5 Mbps.

Figure 3 shows the downstream bandwidth usage for the five individual conference sessions.

Conferencing Application: B

Figure 4 shows access network usage for five concurrent sessions over 300 seconds (five minutes) for the next conferencing application tested. The blue line is the total downstream usage, and the orange line is total upstream usage. Note that the upstream usage hovers around 3 Mbps as each conference session attempts to use as much upstream bandwidth as possible.

Figure 5 shows the upstream bandwidth usage of the five individual conference sessions where each is below 1 Mbps, though the individual sessions sawtooth up and down as the individual conference sessions compete for more bandwidth. This is normal behavior for applications of this type, and did not have a negative impact on stream quality.

Figure 6 shows the downstream bandwidth usage for the five individual conference sessions.

Conferencing Application: C

Figure 7 shows access network usage for the five concurrent sessions over 300 seconds (five minutes) for the third of the applications tested. The blue line is the total downstream usage, and the orange line is total upstream usage. Note that the total upstream usage hovers around 3 Mbps over the five minutes.

Figure 8 shows the upstream bandwidth usage of the five individual conference sessions where each is below 1 Mbps, though the individual sessions sawtooth up and down as the individual conference sessions compete for more bandwidth. This is normal behavior for applications of this type, and did not have a negative impact on stream quality.

Figure 9 shows the downstream bandwidth usage for the five individual conference sessions. Note the scale of this diagram is different because of higher downstream bandwidth usage.

In summary, each of the video conferencing applications supported at least five concurrent sessions over the 25/3 broadband connection. The focus of this analysis is upstream bandwidth usage, and all three video conferencing technologies manage the upstream usage to fit within the provisioned 3 Mbps broadband speed. For at least two of the conferencing applications, there was also sufficient available downstream speed to run other common applications, such as video streaming and web browsing, concurrently with the five conferencing sessions.

Areas of Future Study

Conferencing services have enhanced modes that allow for higher definition video but that also uses more bandwidth. These modes place additional load on the broadband connection and may reduce the number of simultaneous conferences.

An interesting finding is that upstream bandwidth usage out of a home can depend on how other conference participants choose to view the video. Gallery mode uses lower bit rate thumbnail pictures of participants and is the most efficient for a conference. “Pinning” a speaker’s video can cause higher bandwidth out of a home. In addition, users that purchase add-on cameras that provide higher definition video than the camera included with their laptop may see higher upstream usage.

Wired

Proactive Network Maintenance (PNM): Cable Modem Validation Application(s)

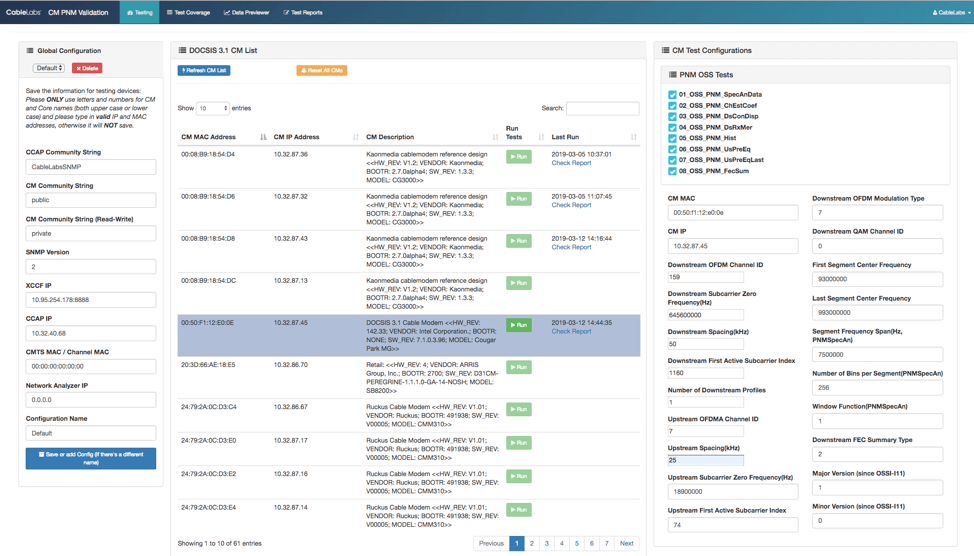

Sometimes, two apps are better than one. We now have two versions of the Cable Modem Validation Application (CMVA) available for download and use: a new lab automation version, and a data exploration version.

Thing One and Thing Two

Lab automation and certification have unique requirements, but investigation and invention require flexibility. Because the CMVA found value as a cable modem (CM) data plotter and browser on top of its original purpose as a lab testing tool, we decided there should be two versions—one focused on each use case.

Sometimes You Feel Like a DUT

The newest, most complex version of CMVA is built specifically for CM Cert-Lab testing and includes several new features and automations:

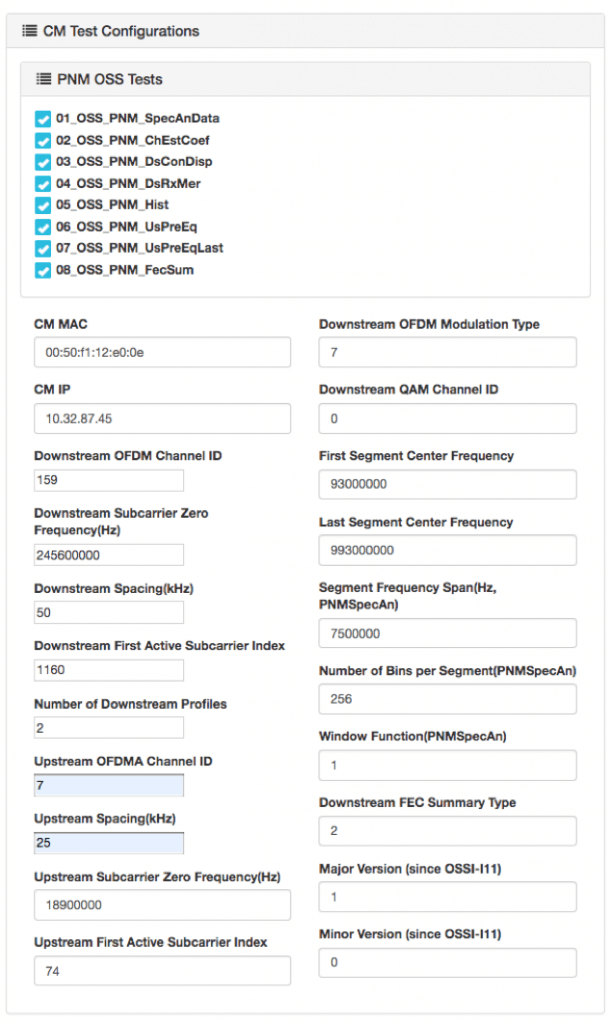

- Improved efficiency for CMVA on certification testing: CMVA now discovers OFDM/OFDMA-based topology information from the CMTS and loads all related channel configuration information automatically for testing. CMVA also synchronizes PNM SNMP SET command parameters with XCCF for better efficiency and greater control.

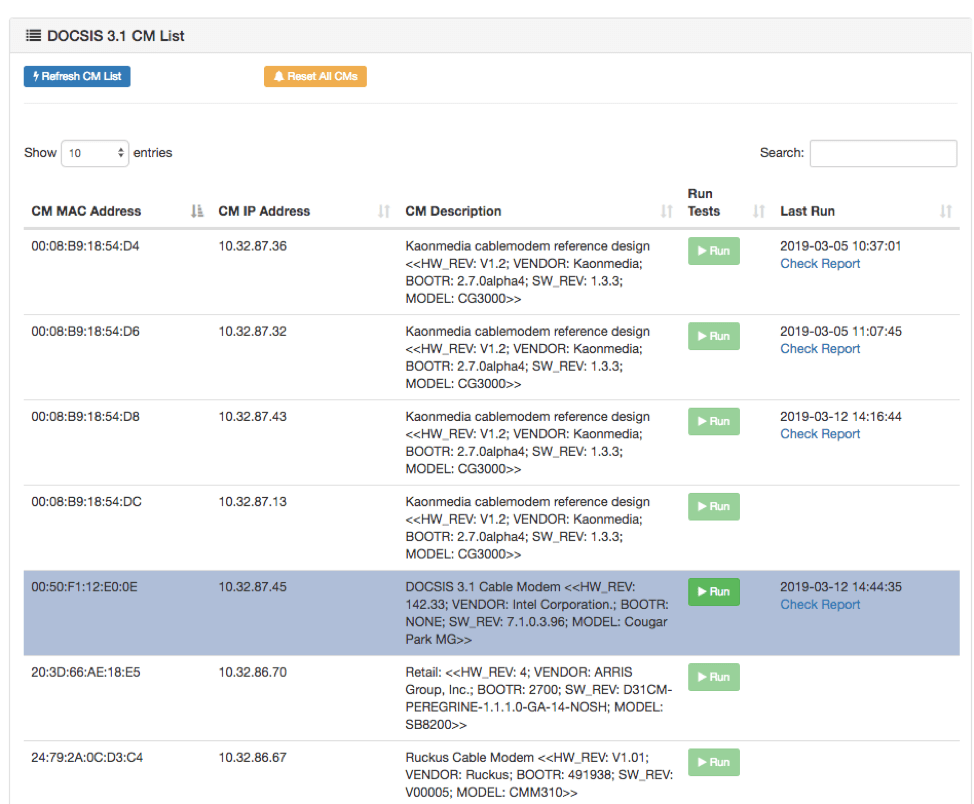

- Automated discovery of the active DOCSIS® 3.1 CM list: Users can easily select CMs with their test configurations automatically filled to start tests with a few clicks.

- CMVA now runs multiple PNM tests sequentially on multiple CMs in parallel with simple clicks on a single user login: The latest test reports are directly served from the CM table. Different users are handled in parallel, as previously.

- CMVA now embeds detailed testing logs into the HTML test report: The log file can be downloaded from the HTML test report. The HTML test report is portable.

- CMVA now keeps copies of raw PNM test files together with the test reports for vendor debugging references: When downloading the test reports, CMVA packages the test logs in raw text, and forms the portable HTML test report into a single archive.

- All the Acceptance Test Plan (ATP) calculation activities are placed in the log file for vendor debugging references.

- We added a function for resetting CMs remotely with one click: This is important for testing and useful for other purposes.

Figure 1: New layout for test and configuration management

Figure 2: Select CM directly from the table to start tests; the latest reports are linked directly in the table for convenience

Figure 3: The test procedures ran last time are tracked, and the configurations are automatically filled

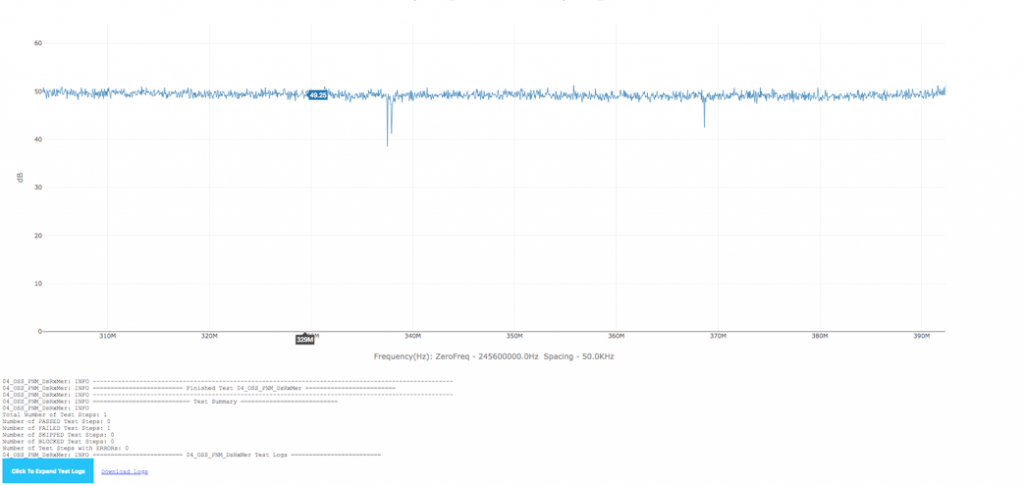

Figure 4: Detailed test logs are embedded directly into the portable HTML test report and can be downloaded as pure text log

All these new features are important for test automation, but some of them are useful for other needs. Go nuts! But if you simply want the basic capabilities that CMVA always provided, you can still get that version.

Sometimes You Don’t

Sometimes you just want a simple way to poll a set of modems and see what you can get. The previous version is a bit simpler, but it still has the validation capabilities if you need them. So, it might be the version that can address most, if not all, of your needs. We use it for many purposes but mainly as a testing and development tool. Here are some specific use cases we’ve encountered:

- Testing ideas in the lab: The PNM Working Group InGeNeOS conducted lab testing, as reported on before, and we used CMVA to grab data from CMs under test.

- Developing applications: As we work to develop our first large-scale PNM base application, inside our prototype PNM Application Environment, we use CMVA to develop theories about how the data can be processed for automated processing.

- Building reports and documenting: So often, we need to capture what certain impairments look like, or obtain a good visualization of a PNM measurement, and CMVA makes that handy.

- Investigating issues: With CMVA, it’s a simple matter to collect data from a pool of CMs and compare the results. This helps us investigate many issues, including changes in firmware versions, CM responsiveness, and other potential issues with plant configuration, software changes and so on.

- Combined Common Collection Framework (XCCF) development and testing: As we develop new capabilities with our XCCF, we can use CMVA to validate its functionality.

If you are a user of CMVA, let us know how you have used it!

Two Can Play at That Game

Although the more complicated testing tool can be used for all these use cases and many more, some users don’t need the automation, overhead and many controls required for automated testing. When you contact us to get an updated version of CMVA, please let us know what you would like to use it for. That way, we can offer you the right version.