When I was a kid, I used to lay in bed at night and try to hold the universe in my head.

Eyes tight shut, I’d let the edges of my mind rush out in all directions, imagining that it was the fabric of space expanding. The planets would rapidly recede from view; I’d soar past billions of stars until the glittering disc of the Milky Way spun before me. But I didn’t stop there. I’d continue onwards and outwards until I’d thrown my mind out so far that I cradled the entire cosmos inside my skull.

Then I learnt that the universe has no edge.

That threw a spanner in the works.

There is – as 10-year-old me discovered – no boundary to the universe, no outside in which it is suspended. It just is. Suddenly, my space explorations faltered. This new knowledge didn’t tessellate with anything I knew about the everyday world in which I was embedded, in which everything was embedded.

Tucked neatly into the rectangular prism of my bed, snug beneath the doona, I tried to imagine a map with no edge. I’d been holding an inky black ball in my head, watching it seethe with the shining threads of galactic superclusters, but every time I tried to delete the boundaries from that thought, my virtual cosmos became slippery. Instead I’d just slide back into the model of the universe that was comfortable – but wasn’t actually real.

I couldn’t force myself to make that radical shift in perspective – which is exactly how I felt when I learnt about Professor Joan Vaccaro’s quantum theory of time.

Vaccaro, a quantum theorist at Griffith University in Queensland, has a theory that posits that time doesn’t just move forwards in a relentless march away from the Big Bang towards chaos, but moves backwards as well – and we can’t tell which timeline we’re in, which technically means we’re in both.

“We’re in a superposition of going into the future as well as the past,” Vaccaro sums it up.

Talking to her is like trying to hold an infinite universe in my head. Our conversation runs in cycles: Vaccaro explains a concept to me, I think I understand it and repeat it back to her for clarity, then she says, “No, not quite, it’s more like this…” Then I attempt to understand and summarise it again, then she says, “No, not quite, it’s more like this…”

I just can’t see the shape of it in my head, can’t shift my brain to encompass a universe in a superposition of past and future. Time is one of the things that’s just true. The sky is blue, water is wet, and time moves forward – never backwards, and certainly not both ways at once.

I confess to Vaccaro that I feel limited by my own perspective – and she tells me that she, of course, had initially felt the very same way.

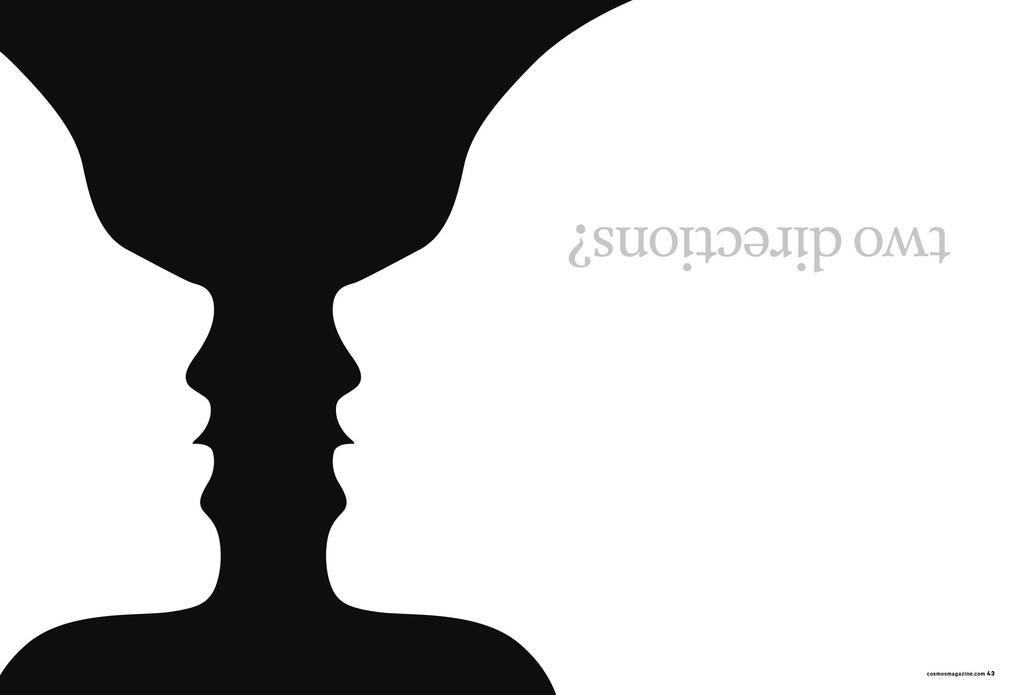

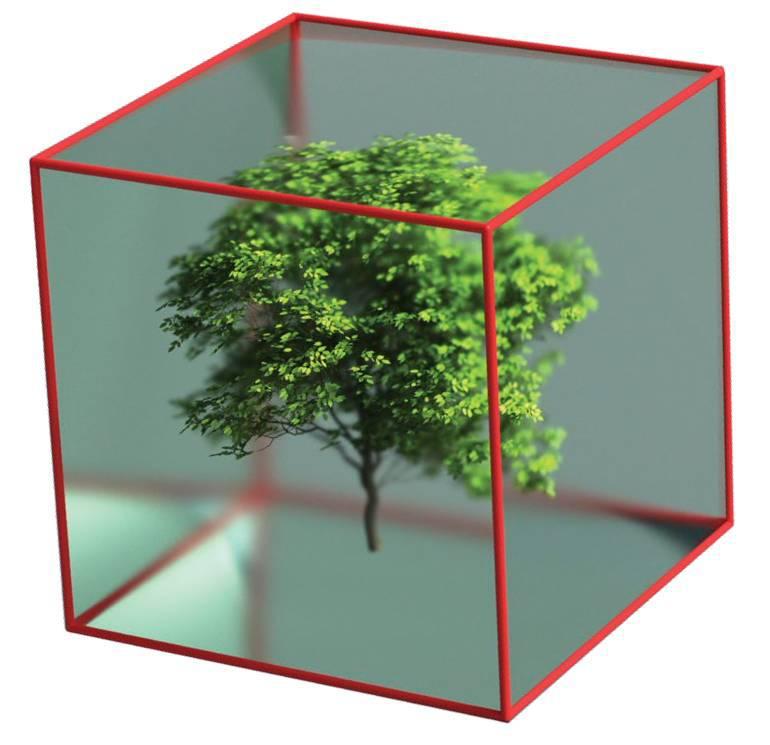

Vaccaro asks if I’ve heard of the Gestalt shift. I start to sift through a mental tangle of particle physics to reach my memory, but she’s already explaining that it’s the experience of seeing something one way, and then suddenly snapping to another. “The most famous example is a three-dimensional box, drawn just with the edges. From one perspective it looks like it’s oriented , that can shift from a different perspective. It’s like that – you have to force your imagination to