‘I Am a Practicing Catholic and I Am a Proud Jew’

The Jewish cemetery in Ferrara, Italy, is a melancholy place nestled against the walls that encircle the medieval city. Its 800 gravestones are bunched in clusters amid overgrown grass, fallen leaves, and brooding trees. The impressive expanse is evidence of what had been, before the Second World War, a large, vibrant Jewish community, now reduced to a few dozen souls. An occasional visitor comes to photograph the jarringly modernist gravestone of Giorgio Bassani, the author of the novel The Garden of the Finzi-Continis, which opens with a description of the Finzi-Contini family’s mausoleum here. Others come to see the memorials to some of the 150 Jews of Ferrara who were deported to Nazi death camps.

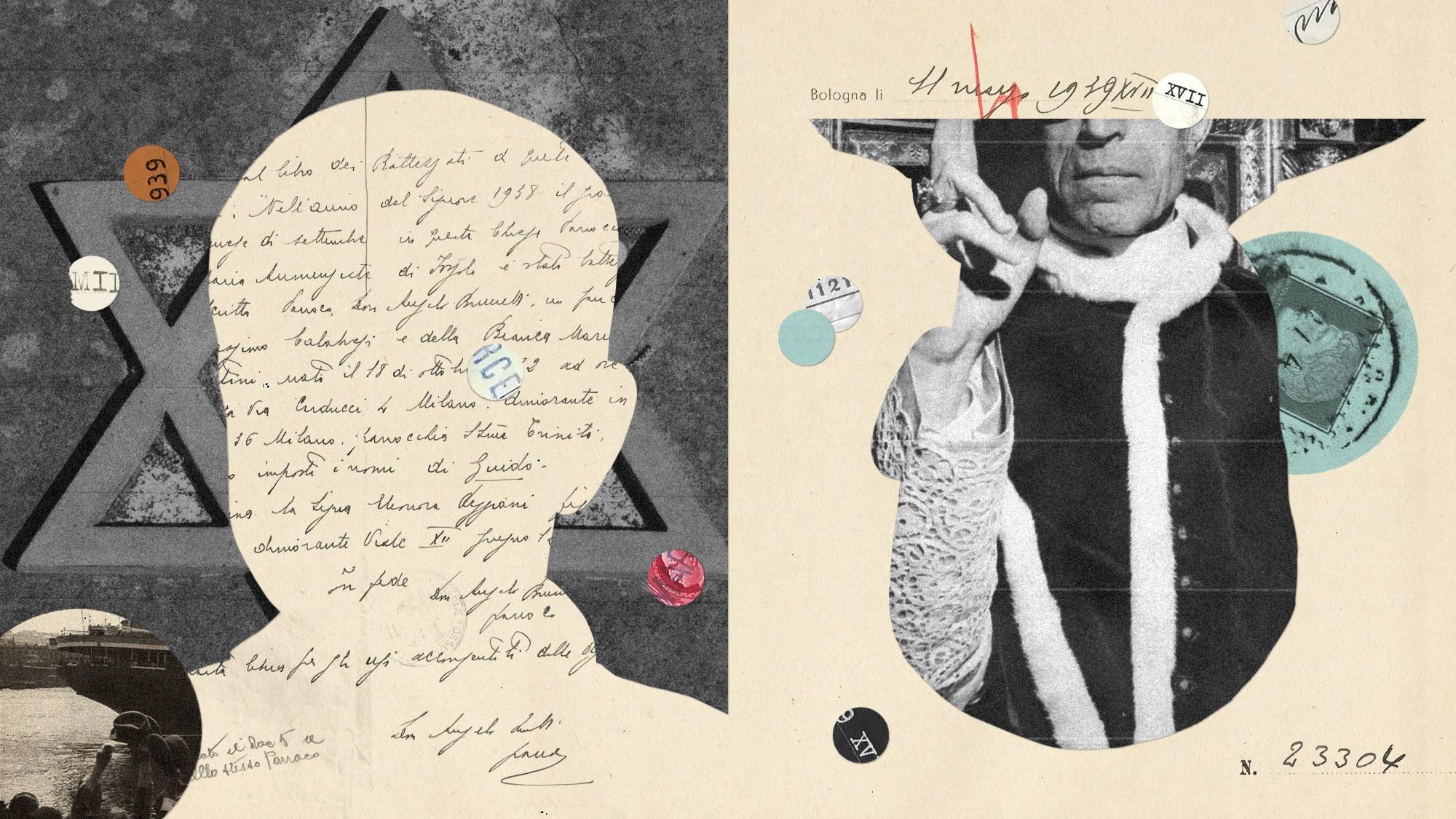

While walking through the cemetery one day last year—I was in Ferrara for the launch of the Italian edition of my book The Pope at War, about Italy and the Vatican during the Second World War—I came across a group of gravestones bearing the name Calabresi. One in particular caught my eye. I stopped to look more closely at the pockmarked granite slab, which lay in a sea of dandelions. It was the gravestone of a man named Massimo Calabresi. Unlike many of the others in the cemetery, it displayed no Hebrew, only Italian. It gave Massimo’s place of birth (in 1903) as Ferrara and the place of death (in 1988), curiously, as New Haven, Connecticut. The gravestone had another unusual feature. At the bottom, under the inscription for Massimo, were the words, in Italian:

in memory of his wife

Bianca Maria Finzi Contini

buried in New Haven CT USA

For some reason, Bianca’s remains had not joined Massimo’s in Ferrara.

The name Calabresi got my attention: It brought to mind the prominent American jurist Guido Calabresi. I had never met him, but I knew that he had served as dean at Yale Law School before being appointed to the federal bench by his former student President Bill Clinton. I also knew that he came from an Italian Jewish family and had emigrated to America when he was a child, as Italy imposed anti-Semitic “racial” laws and war engulfed Europe. And I had heard something else: that despite his Jewish ancestry, he was a devout Roman Catholic.

Given the surname and the New Haven reference, the gravestone in Ferrara seemed likely to hold a connection to the American professor and judge. And it made me wonder: How had the family managed to find their way out of Italy? And why had only Massimo made his way back?

By coincidence, shortly after my visit to the Jewish Cemetery, a friend emailed me to report that he hadto an old law-school professor of his—Guido Calabresi, then 90 and still living near New Haven. I decided to take a deeper look at the Vatican’s records to see if they had any information about the Calabresi family. And they did.

You’re reading a preview, subscribe to read more.

Start your free 30 days