AUGUSTINE SEDGEWICK is the author of Coffeeland: One Man's Dark Empire and the Making of Our Favorite Drug, winner of the 2022 Cherasco Prize, and the forthcoming Fatherhood: A History of Love and Power.

When Henry Thoreau was a boy, he asked his mother, Cynthia, what he should do when he grew up. “You can buckle on your knapsack,” she told him, “and roam abroad to seek your fortune.” It was a familiar route into the world for second sons especially, but for Henry the possibility was too awful to contemplate. As tears filled his eyes, his older sister, Helen, came to his rescue. “No,” she assured him, “you shall not go: You shall stay at home and live with us.” So Henry did, virtually all his life, and paid his way in pencils.

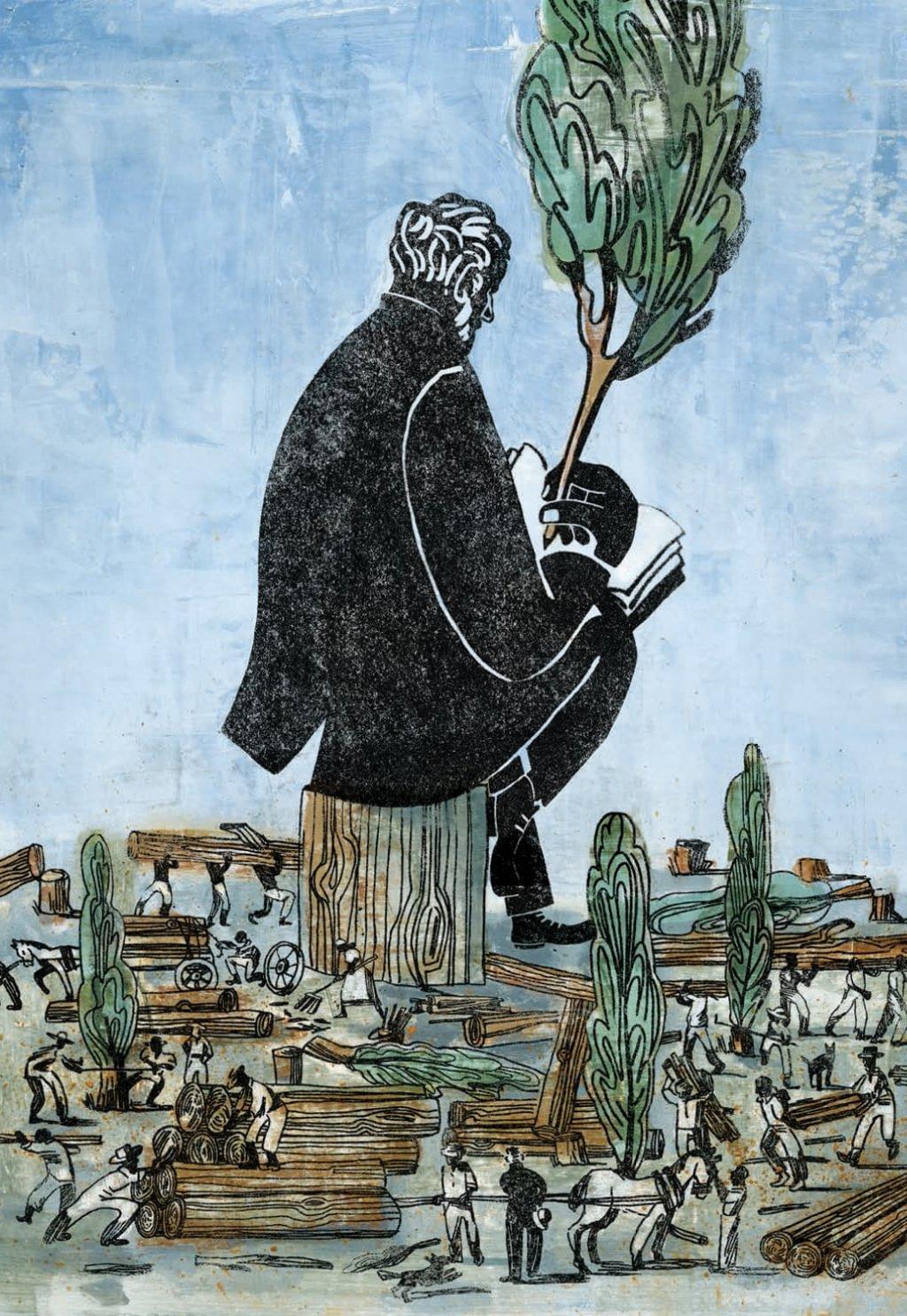

John Thoreau, Henry's father, had entered the pencil business in 1823, after his brother-in-law happened upon a vein of plumbago, or graphite, in the New Hampshire hills. By then, John and Cynthia had four children, including Henry, and needed a lucky break. As a young man, John had borrowed against his expected inheritance to open a store. But the early death of his father, combined with mismanagement of the family estate, meant that John's inheritance never came through. His store failed, and afterward he struggled to earn a living beyond his debt by clerking, farming, and ultimately selling his gold wedding ring.

Once John got started in pencils, he and Cynthia were determined to recover the economic security and social standing they had lost. Pencils made by the family firm, initially called J. Thoreau & Co., quickly gained local recognition, winning an award in the first year of production, but financial success still proved elusive.

More than a decade later, John proposed that Henry apprentice himself to a cabinetmaker—sensible training for a future pencil manufacturer. But when Henry passed Harvard's entrance exam in 1833, Cynthia insisted that he attend, even if sending him to the college would be a financial stretch. In 1835, near the end of Henry's second year, the Thoreaus gave up their brick house in Concord and moved into a smaller one with two of John's spinster sisters.

Fifteen miles away in Cambridge, Henry felt their sacrifice keenly. In November 1835, the Board of Overseers of Harvard College voted to allow enrolled students to take up to 13 weeks off to earn money teaching, and Henry was one of the first to apply for leave. A month later, he became the master of a one-room schoolhouse and 70 boys in Canton, about 20 miles to the south. By the time he returned to Cambridge in the spring, he had acquired a new contempt for Harvard's classical curriculum as well as symptoms of what historians now think was the tuberculosis that would eventually kill him.

In May 1836, increasingly sick, Henry left Harvard again, and this time it wasn't clear whether he would be going back—whether he had the strength, or his family the money. Late in the summer, just before the start of the fall term, Henry and his father packed up boxes of pencils and set out on a trip to New York, where they hoped to earn money for tuition.

Henry returned to Cambridge that fall with mixed feelings. He finished 19th in his graduating class of 41, good enough to earn him a prize of $25 and a prestigious speaking role in the commencement ceremony. He and two other students were assigned to speak on a theme of special relevance: “The Commercial Spirit of Modern Times, Considered in Its Influence on the Political, Moral, and Literary Character of a Nation.” Many members of his class were struggling to find jobs amid an economic crisis that would come to be known as the Panic of 1837. Thoreau wondered whether they should