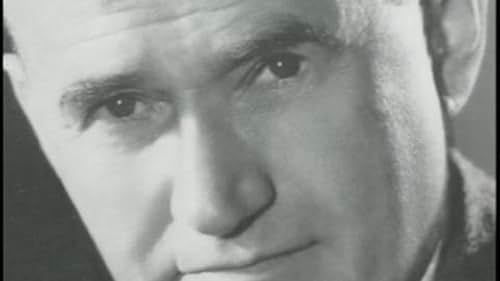

Sam Peckinpah(1925-1984)

- Writer

- Director

- Producer

"If they move", commands stern-eyed

William Holden, "kill 'em". So

begins The Wild Bunch (1969), Sam

Peckinpah's bloody, high-body-count eulogy to the mythologized Old

West. "Pouring new wine into the bottle of the Western, Peckinpah

explodes the bottle", observed critic

Pauline Kael. That exploding bottle also

christened the director with the nickname that would forever define his

films and reputation: "Bloody Sam".

David Samuel Peckinpah was born and grew up in Fresno, California, when it was still a sleepy town. Young Sam was a loner. The child's greatest influence was grandfather Denver Church, a judge, congressman and one of the best shots in the Sierra Nevadas. Sam served in the US Marine Corps during World War II but - to his disappointment - did not see combat. Upon returning to the US he enrolled in Fresno State College, graduating in 1948 with a B.A. in Drama. He married Marie Selland in Las Vegas in 1947 and they moved to Los Angeles, where he enrolled in the graduate Theater Department of the University of Southern California the next year. He eventually took his Masters in 1952.

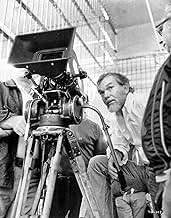

After drifting through several jobs -- including a stint as a floor-sweeper on The Liberace Show (1952) -- Sam got a job as Dialogue Director on Riot in Cell Block 11 (1954) for director Don Siegel. He worked for Siegel on several films, including Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), in which Sam played Charlie Buckholtz, the town meter reader. Peckinpah eventually became a scriptwriter for such TV programs as Gunsmoke (1955) and The Rifleman (1958) (which he created as an episode of Dick Powell's Zane Grey Theatre (1956) titled "The Sharpshooter' in 1958). In 1961, as his marriage to Selland was coming to an end, he directed his first feature film, a western titled The Deadly Companions (1961) starring \Brian Keith and Maureen O'Hara. However, it was with his second feature, Ride the High Country (1962), that Peckinpah really began to establish his reputation. Featuring Joel McCrea and Randolph Scott (in his final screen performance), its story about two aging gunfighters anticipated several of the themes Peckinpah would explore in future films, including the controversial "The Wild Bunch". Following "Ride the High Country" he was hired by producer Jerry Bresler to direct Major Dundee (1965), a cavalry-vs.-Indians western starring Charlton Heston. It turned out to be a film that brought to light Peckinpah's volatile reputation. During hot, on-location work in Mexico, his abrasive manner, exacerbated by booze and marijuana, provoked usually even-keeled Heston to threaten to run him through with a cavalry saber. However, when the studio later considered replacing Peckinpah, it was Heston who came to Sam's defense, going so far as to offer to return his salary to help offset any overages. Ironically, the studio accepted and Heston wound up doing the film for free.

Post-production conflicts led to Sam engaging in a bitter and ultimately losing battle with Bresler and Columbia Pictures over the final cut and, as a result, the disjointed effort fizzled at the box office. It was during this period that Peckinpah met and married his second wife, Mexican actress Begoña Palacios. However, the reputation he earned because of the conflicts on "Major Dundee" contributed to Peckinpah being replaced as director on his next film, the Steve McQueen film The Cincinnati Kid (1965), by Norman Jewison.

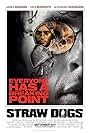

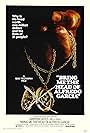

His second marriage now failing, Peckinpah did not get another feature project for two years. However, he did direct a powerful adaptation of Katherine Anne Porter's 'Noon Wine" for Noon Wine (1966)). This, in turn, helped relaunch his feature career. He was hired by Warner Bros. to direct the film for which he is, justifiably, best remembered. The success of "The Wild Bunch" rejuvenated his career and propelled him through highs and lows in the 1970s. Between 1970-1978 he directed The Ballad of Cable Hogue (1970), Straw Dogs (1971), Junior Bonner (1972), The Getaway (1972), Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid (1973), Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974), The Killer Elite (1975), Cross of Iron (1977) and Convoy (1978). Throughout this period controversy followed him. He provoked more rancor over his use of violence in "Straw Dogs", introduced Ali MacGraw to Steve McQueen in "The Getaway", fought with MGM's chief James T. Aubrey over his vision for "Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid" that included the casting of Bob Dylan in an unscripted role as a character called "Alias." His last solid effort was the WW II anti-war epic "Cross of Iron", about a German unit fighting on the Russian front, with Maximilian Schell and James Coburn, bringing the picture in successfully despite severe financial problems.

Peckinpah lived life to its fullest. He drank hard and abused drugs, producers and collaborators. At the end of his life he was considering a number of projects including the Stephen King-scripted "The Shotgunners". He was returning from Mexico in December 1984 when he died from heart failure in a hospital in Inglewood, California, at age 59. At a standing-room-only gathering that held at the Directors Guild the following month, Coburn remembered the director as a man "who pushed me over the abyss and then jumped in after me. He took me on some great adventures". To which Robert Culp added that what is surprising is not that Sam only made fourteen pictures, but that given the way he went about it, he managed to make any at all.

David Samuel Peckinpah was born and grew up in Fresno, California, when it was still a sleepy town. Young Sam was a loner. The child's greatest influence was grandfather Denver Church, a judge, congressman and one of the best shots in the Sierra Nevadas. Sam served in the US Marine Corps during World War II but - to his disappointment - did not see combat. Upon returning to the US he enrolled in Fresno State College, graduating in 1948 with a B.A. in Drama. He married Marie Selland in Las Vegas in 1947 and they moved to Los Angeles, where he enrolled in the graduate Theater Department of the University of Southern California the next year. He eventually took his Masters in 1952.

After drifting through several jobs -- including a stint as a floor-sweeper on The Liberace Show (1952) -- Sam got a job as Dialogue Director on Riot in Cell Block 11 (1954) for director Don Siegel. He worked for Siegel on several films, including Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), in which Sam played Charlie Buckholtz, the town meter reader. Peckinpah eventually became a scriptwriter for such TV programs as Gunsmoke (1955) and The Rifleman (1958) (which he created as an episode of Dick Powell's Zane Grey Theatre (1956) titled "The Sharpshooter' in 1958). In 1961, as his marriage to Selland was coming to an end, he directed his first feature film, a western titled The Deadly Companions (1961) starring \Brian Keith and Maureen O'Hara. However, it was with his second feature, Ride the High Country (1962), that Peckinpah really began to establish his reputation. Featuring Joel McCrea and Randolph Scott (in his final screen performance), its story about two aging gunfighters anticipated several of the themes Peckinpah would explore in future films, including the controversial "The Wild Bunch". Following "Ride the High Country" he was hired by producer Jerry Bresler to direct Major Dundee (1965), a cavalry-vs.-Indians western starring Charlton Heston. It turned out to be a film that brought to light Peckinpah's volatile reputation. During hot, on-location work in Mexico, his abrasive manner, exacerbated by booze and marijuana, provoked usually even-keeled Heston to threaten to run him through with a cavalry saber. However, when the studio later considered replacing Peckinpah, it was Heston who came to Sam's defense, going so far as to offer to return his salary to help offset any overages. Ironically, the studio accepted and Heston wound up doing the film for free.

Post-production conflicts led to Sam engaging in a bitter and ultimately losing battle with Bresler and Columbia Pictures over the final cut and, as a result, the disjointed effort fizzled at the box office. It was during this period that Peckinpah met and married his second wife, Mexican actress Begoña Palacios. However, the reputation he earned because of the conflicts on "Major Dundee" contributed to Peckinpah being replaced as director on his next film, the Steve McQueen film The Cincinnati Kid (1965), by Norman Jewison.

His second marriage now failing, Peckinpah did not get another feature project for two years. However, he did direct a powerful adaptation of Katherine Anne Porter's 'Noon Wine" for Noon Wine (1966)). This, in turn, helped relaunch his feature career. He was hired by Warner Bros. to direct the film for which he is, justifiably, best remembered. The success of "The Wild Bunch" rejuvenated his career and propelled him through highs and lows in the 1970s. Between 1970-1978 he directed The Ballad of Cable Hogue (1970), Straw Dogs (1971), Junior Bonner (1972), The Getaway (1972), Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid (1973), Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974), The Killer Elite (1975), Cross of Iron (1977) and Convoy (1978). Throughout this period controversy followed him. He provoked more rancor over his use of violence in "Straw Dogs", introduced Ali MacGraw to Steve McQueen in "The Getaway", fought with MGM's chief James T. Aubrey over his vision for "Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid" that included the casting of Bob Dylan in an unscripted role as a character called "Alias." His last solid effort was the WW II anti-war epic "Cross of Iron", about a German unit fighting on the Russian front, with Maximilian Schell and James Coburn, bringing the picture in successfully despite severe financial problems.

Peckinpah lived life to its fullest. He drank hard and abused drugs, producers and collaborators. At the end of his life he was considering a number of projects including the Stephen King-scripted "The Shotgunners". He was returning from Mexico in December 1984 when he died from heart failure in a hospital in Inglewood, California, at age 59. At a standing-room-only gathering that held at the Directors Guild the following month, Coburn remembered the director as a man "who pushed me over the abyss and then jumped in after me. He took me on some great adventures". To which Robert Culp added that what is surprising is not that Sam only made fourteen pictures, but that given the way he went about it, he managed to make any at all.