Hugo Friedhofer(1901-1981)

- Music Department

- Composer

- Soundtrack

Hugo Friedhofer -- how many times have you seen that name in the

credits of 1930s and '40s movies for "orchestration" or "musical

arranger" and thought -- Gee, what a busy guy! He was, and, ironically,

much of that work went uncredited. He is not usually mentioned with the

great film composers of early Hollywood, but he was very much an equal

and as prolific once he received the opportunities to compose as well.

Friedhofer began studying the cello at age 13. In 1917, he dropped out

of high school in support of a teacher who had been fired for radical

and anti-war beliefs. He worked as a cellist for the People's Symphony

Orchestra in San Francisco (always a liberal kind of place). He married

quite young at 19 and had a child by the age of 22. He quickly put his

music expertise to a working life by playing in theater orchestras and

accompanying silent films and stage shows between features. He also

started writing arrangements of music and worked at the Granada Theater

(became the Paramount in 1931), with the opportunity to write some

incidental music.

Friedhofer came to Los Angeles in the later 1920s and became a friend of the violinist George Lipschultz, who just happened to be the musical director at Twentieth Century Fox. It was 1929, and Lipschultz asked him to fill in a musician spot for film music recording at a small studio. That was the beginning of Friedhofer's career in films. When this small studio was taken over by Fox, he and other musicians were on the street. But he was brought to the notice of Erich Korngold, a relatively new film composer at Warner Bros. where Max Steiner was king. Friedhofer was hired by Warner Bros soon after to arrange scores for musicals and orchestrate scores-mostly for these two composers. Including orchestrating all of Korngold's movie scores and fifty of Steiner's, Friedhofer would orchestrate or musically direct 105 films into the mid 1950s during his career.

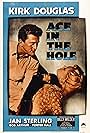

But he was already doing significant film composing as well from 1930 along with incidental and stock music for several studios before his stay at Warner. Friedhofer's developing style was in the romantic vein of his contemporaries. He studied composition with Ernst Toch after aiding the composer with contributions to Peter Ibbetson (1935) at Paramount. With the move to Warner, Friedhofer's problem became being just too valuable as an orchestrator and musical director for Warner to free him for composing assignments until the late 1930s. With tight budgets and the need for musical managers to wear several hats, Friedhofer's legendary efficiency was hard to give up. His first full film score was for Samuel Goldwyn's The Adventures of Marco Polo (1938) after being recommended by another film composer great Alfred Newman. His first for Warner's was The Oklahoma Kid (1939) (with James Cagney debuting as a cowboy!). He did not get credit for this nor for The Mark of Zorro (1940) (co-work with Newman) and Santa Fe Trail (1940) both in 1940. Into and after the war years Friedhofer was very busy -- but still not getting the composing credit due -- as for Gilda (1946). All told, he was not credited as composer for some 120 films.

Friedhofer broke from the confines of Warner Bros. finally in 1946 to freelance and received the grand prize right off. Again, it was Newman who recommended him for scoring Goldwyn's wonderful post-war drama of adjustment The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), and Friedhofer showed his power as composer with a score that engaged the story at every turn and most deservedly won the Oscar for Best Score. Other memorable credited scores included such classics as: the gripping music for Lifeboat (1944), directed by Alfred Hitchcock; the delightful Christmas strings score of The Bishop's Wife (1947); and the soaring music for 'Ingrid Bergman' in Joan of Arc (1948).

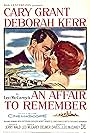

Though he continued in demand, much of Friedhofer's scoring output through the 1950s went to films mostly relegated to Saturday mornings these days, but there were notables, as the 1957 duo An Affair to Remember (1957) and the well-received The Sun Also Rises (1957). And the next year came the engaging and thought-provoking The Barbarian and the Geisha (1958) (a fine performance by John Wayne) under the always versatile direction of John Huston. He also did some TV episodic and mini-movie music through the 1960s in addition to more films.

Friedhofer had all the qualities of an accomplished, indeed, incisive and intuitive film composer -- proved with a total of eight Oscar nominations -- and yet he was his own worst enemy. Anxieties about his abilities brought self-criticism and doubts that boiled out in a misanthropic view of the world in general that no amount of praise from public or friends could dislodge. At the least he should have believed that he had succeeded in grand style -- with nearly 250 pieces of screen music as a realistic basis for affirmation.

Friedhofer came to Los Angeles in the later 1920s and became a friend of the violinist George Lipschultz, who just happened to be the musical director at Twentieth Century Fox. It was 1929, and Lipschultz asked him to fill in a musician spot for film music recording at a small studio. That was the beginning of Friedhofer's career in films. When this small studio was taken over by Fox, he and other musicians were on the street. But he was brought to the notice of Erich Korngold, a relatively new film composer at Warner Bros. where Max Steiner was king. Friedhofer was hired by Warner Bros soon after to arrange scores for musicals and orchestrate scores-mostly for these two composers. Including orchestrating all of Korngold's movie scores and fifty of Steiner's, Friedhofer would orchestrate or musically direct 105 films into the mid 1950s during his career.

But he was already doing significant film composing as well from 1930 along with incidental and stock music for several studios before his stay at Warner. Friedhofer's developing style was in the romantic vein of his contemporaries. He studied composition with Ernst Toch after aiding the composer with contributions to Peter Ibbetson (1935) at Paramount. With the move to Warner, Friedhofer's problem became being just too valuable as an orchestrator and musical director for Warner to free him for composing assignments until the late 1930s. With tight budgets and the need for musical managers to wear several hats, Friedhofer's legendary efficiency was hard to give up. His first full film score was for Samuel Goldwyn's The Adventures of Marco Polo (1938) after being recommended by another film composer great Alfred Newman. His first for Warner's was The Oklahoma Kid (1939) (with James Cagney debuting as a cowboy!). He did not get credit for this nor for The Mark of Zorro (1940) (co-work with Newman) and Santa Fe Trail (1940) both in 1940. Into and after the war years Friedhofer was very busy -- but still not getting the composing credit due -- as for Gilda (1946). All told, he was not credited as composer for some 120 films.

Friedhofer broke from the confines of Warner Bros. finally in 1946 to freelance and received the grand prize right off. Again, it was Newman who recommended him for scoring Goldwyn's wonderful post-war drama of adjustment The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), and Friedhofer showed his power as composer with a score that engaged the story at every turn and most deservedly won the Oscar for Best Score. Other memorable credited scores included such classics as: the gripping music for Lifeboat (1944), directed by Alfred Hitchcock; the delightful Christmas strings score of The Bishop's Wife (1947); and the soaring music for 'Ingrid Bergman' in Joan of Arc (1948).

Though he continued in demand, much of Friedhofer's scoring output through the 1950s went to films mostly relegated to Saturday mornings these days, but there were notables, as the 1957 duo An Affair to Remember (1957) and the well-received The Sun Also Rises (1957). And the next year came the engaging and thought-provoking The Barbarian and the Geisha (1958) (a fine performance by John Wayne) under the always versatile direction of John Huston. He also did some TV episodic and mini-movie music through the 1960s in addition to more films.

Friedhofer had all the qualities of an accomplished, indeed, incisive and intuitive film composer -- proved with a total of eight Oscar nominations -- and yet he was his own worst enemy. Anxieties about his abilities brought self-criticism and doubts that boiled out in a misanthropic view of the world in general that no amount of praise from public or friends could dislodge. At the least he should have believed that he had succeeded in grand style -- with nearly 250 pieces of screen music as a realistic basis for affirmation.