Bachrach V (1) (1) .Doc Digest

Bachrach V (1) (1) .Doc Digest

Uploaded by

Aljeane TorresCopyright:

Available Formats

Bachrach V (1) (1) .Doc Digest

Bachrach V (1) (1) .Doc Digest

Uploaded by

Aljeane TorresOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Bachrach V (1) (1) .Doc Digest

Bachrach V (1) (1) .Doc Digest

Uploaded by

Aljeane TorresCopyright:

Available Formats

Bachrach v. Seifert [G.R. No. L-2659. October 12, 1950.] Facts: The deceased E. M.

Bachrach, who left no forced heir except his widow Mary McDonald Bachrach, in his last will and testament made various legacies in cash and willed the remainder of his estate. The estate of E. M. Bachrach, as owner of 108,000 shares of stock of the Atok-Big Wedge Mining Co., Inc., received from the latter 54,000 shares representing 50 per cent stock dividend on the said 108,000 shares. On June 10, 1948, Mary McDonald Bachrach, as usufructuary or life tenant of the estate, petitioned the lower court to authorize the Peoples Bank and Trust Company, as administrator of the estate of E. M. Bachrach, to transfer to her the said 54,000 shares of stock dividend by indorsing and delivering to her the corresponding certificate of stock, claiming that said dividend, although paid out in the form of stock, is fruit or income and therefore belonged to her as usufructuary or life tenant. Sophie Siefert and Elisa Elianoff, legal heirs of the deceased, opposed said petition on the ground that the stock dividend in question was not income but formed part of the capital and therefore belonged not to the usufructuary but to the remainderman. While appellants admit that a cash dividend is an income, they contend that a stock dividend is not, but merely represents an addition to the invested capital. Issue: Whether or not a dividend is an income and whether it should go to the usufructuary. Held: The usufructuary shall be entitled to receive all the natural, industrial, and civil fruits of the property in usufruct. The 108,000 shares of stock are part of the property in usufruct. The 54,000 shares of stock dividend are civil fruits of the original investment. They represent profits, and the delivery of the certificate of stock covering said dividend is equivalent to the payment of said profits. Said shares may be sold independently of the original shares, just as the offspring of a domestic animal may be sold independently of its mother. If the dividend be in fact a profit, although declared in stock, it should be held to be income. A dividend, whether in the form of cash or stock, is income and, consequently, should go to the usufructuary, taking into consideration that a stock dividend as well as a cash dividend can be declared only out of profits of the corporation, for if it were declared out of the capital it would be a serious violation of the law. Under the Massachusetts rule, a stock dividend is considered part of the capital and belongs to the remainderman; while under the Pennsylvania rule, all earnings of a corporation, when declared as dividends in whatever form, made during the lifetime of the usufructuary, belong to the latter. The Pennsylvania rule is more in accord with our statutory laws than the Massachusetts rule. Bachrach Motors v. Talisay-Silay Milling Plaintiff-appellee: Bachrach Motor Co., Inc. Defendants-appellees: Talisay-Silay Milling Co. et al. Intervenor-appellant: Philippine National Bank

Facts: On 22 December 1923, the Talisay-Silay Milling Co., Inc., was indebted to the PNB. To secure the payment of its debt, it succeeded in inducing its planters, among whom was Mariano Lacson Ledesma, to mortgage their land to the bank. And in order to compensate those planters for the risk they were running with their property under that mortgage, the aforesaid central, by a resolution passed on the same date, and amended on 23 March 1928, undertook to credit the owners of the plantation thus mortgaged every year with a sum equal to 2% of the debt secured according to the yearly balance, the payment of the bonus being made at once, or in part from time to time, as soon as the central became free of its obligations to the bank, and of those contracted by virtue of the contract of supervision, and had funds which might be so used, or as soon as it obtained from said bank authority to make such payment. <It seems Mariano Lacson Ledesma is indebted from Bachrach Motor; the circumstance of which is not found in the case facts.> Bachrach Motor Co., Inc. filed a complaint against the Talisay-Silay Milling Co., Inc., for the delivery of the amount of P13,850 or promissory notes or other instruments of credit for that sum payable on 30 June 1930, as bonus in favor of Mariano Lacson Ledesma. The complaint further prays that the sugar central be ordered to render an accounting of the amounts it owes Mariano Lacson Ledesma by way of bonus, dividends, or otherwise, and to pay Bachrach Motors a sum sufficient to satisfy the judgment mentioned in the complaint, and that the sale made by said Mariano Lacson Ledesma be declared null and void. The PNB filed a third party claim alleging a preferential right to receive any amount which Mariano Lacson Ledesma might be entitled from Talisay-Silay Milling as bonus. Talisay-Silay answered the complaint that Mariano Lacson Ledesmas credit (P7,500) belonged to Cesar Ledesma because he had purchase it. Cesar Ledesma claimed to be an owner by purchase in good faith. At the trial all the parties agreed to recognize and respect the sale made in favor of Cesar Ledesma of the P7,500 part of the credit in question, for which reason the trial court dismissed the complaint and cross-complaint against Cesar Ledesma authorizing the central to deliver to him the sum of P7,500. And upon conclusion of the hearing, the court held that the Bachrach Motor Co., Inc., had a preferred right to receive the amount of P11,076.02 which was Mariano Lacson Ledesmas bonus, and it ordered the central to deliver said sum to Bachrach Motors. PNB appealed. The Supreme Court affirmed the judgment appealed from, as it found no merit in the appeal;, without express finding as to costs. 1. Civil Fruits under Article 355 of the Civil Code Article 355 of the Civil Code considers three things as civil fruits: First, the rents of buildings; second, the proceeds from leases of lands; and, third, the income from perpetual or life annuities, or other similar sources of revenue. According to the context of the law, the phrase u otras analogas refers only to rents or income, for the adjectives otras and analogas agree with the noun rentas, as do also the other adjectives perpetuas and vitalicias. The civil fruits the Civil Code understands one of three and only three things, to wit: the rent of a building, the rent of land, and certain kinds of income. 2. Bonus not a civil fruit; not an income of the land The amount of the bonus, according to the resolution of the central granting it, is not based upon the value, importance or any other circumstance of the mortgaged property, but upon the

total value of the debt thereby secured, according to the annual balance, which is something quite distinct from and independent of the property referred to. As the bonus is not obtained from the land, it is not civil fruits of that land. It is neither rent of buildings, proceeds from lease of lands, or income under Article 355 of the Civil Code. BERNARDO v BATACLAN FACTS: Plaintiff Vicente Bernardo acquired a parcel of land from Pastor Samonte thru a contract of sale. Thereafter, Bernardo instituted a case against said vendor to secure possession of the land. Bernardo was able to obtain a favorable decision from the court. The plaintiff found the defendant herein, Catalino Bataclan, in the said premises. It appears that he has been authorized by former owners, as far back as 1922, to clear the land and make improvements thereon. Thus, plaintiff instituted a case against Bataclan in the Court of First Instance of Cavite. In this case, plaintiff was declared the owner of the land but the defendant was held to be a possessor in good faith, entitled to reimbursement in the total sum of P1,642, for work done and improvements made. Both parties appealed the decision. The court thereafter made some modifications by allowing the defendant to recover compensation amounting to P2,212 and by reducing the price at which the plaintiff could require the defendant to purchase the land in question from P300 down to P200 per hectare. Plaintiff was likewise given 30 days from the date when the decision became final to exercise his option, either to sell the land to the defendant or to buy the improvements from him. On January 9, 1934, the plaintiff conveyed to the court his desire "to require the defendant to pay him the value of the land at the rate of P200 per hectare or a total price of P18,000 for the whole tract of land." The defendant indicated that he was unable to pay the land and, on January 24, 1934, an order was issued giving the plaintiff 30 days within which to pay the defendant the sum of P2,212. Subsequently, on April 24, 1934, the court below, at the instance of the plaintiff and without objection on the part of the defendant, ordered the sale of the land in question at public auction. The land was sold on April 5, 1935 to Toribio Teodoro for P8,000. ISSUE: WON DEFENDANT BATACLAN IS STILL ENTITLED TORECOVER THE COURT MANDATED COMPENSATION ARISINGFROM THE SALE OF THE PROPERTY TO TORIBIO HELD: NO. Manresa, basing on Art 448 of the NCC, where the planter, builder or sower has acted in good faith, a conflict of rights arises between the owners and it becomes necessary to protect the owner of the improvements without causing injustice to the owner of the land. The law provided a just and equitable solution by giving the owner of the land the option to acquire the improvements after payment of the proper indemnity or to oblige the builder or planter to pay for the land and the sower to pay the proper rent. In this case, the plaintiff, as owner of the land, chose to require the defendant, as owner of the improvements to pay for the land. The defendant avers that he is a possessor in good faith and that the amount of P2,212 to which he is entitled has not yet been paid to him. Defendant further claims that he has a right tor etain the land in accordance with the provisions of article 453 of the Civil Code. While the said argument is legally tenable, the same must perforce be denied because defendant Bataclan has lost his right of retention as he failed to pay for the land. The law, as we have already said, requires no more than that the owner of the land should choose between indemnifying the owner of t h e i m p r o v e m e n t s o r r e q u i r i n g t h e l a t t e r t o p a y f o r t h e land.

GNACIO v HILARIO Facts: Elias Hilario and his wife Dionisia Dres filed a complaint a g a i n s t D a m i a n , F r a n c i s c o a n d L u i s I g n a c i o c o n c e r n i n g t h e ownership of a parcel of land, partly rice-land and partly residential. After the trial of the case, the lower court under Judge Alfonso Felix, endered judgment holding Hilario and Dres as the legal owners of the whole property but conceding to the Ignacios the ownership of the houses and granaries built by them on the residential portion with the rights of a possessor in good faith, in accordance with article361 of the Civil Code. Subsequently, in a motion filed in the same CFI (now handled by respondent Judge Hon. Felipe Natividad), Hilario and Dres prayed for an order of execution alleging that since they chose neither to pay the Ignacios for the buildings nor to sell to them the residential lot, the Ignacios should be ordered to remove the structure at their own expense and to restore Hilario and Dres in the possession of said lot. After hearing, the motion was granted by Judge Natividad. Hence, the petition for certiorari was filed by the Ignacios praying for (a) a restraint and annulment of the order of execution issued by Judge Natividad; (b) an order to compel Hilario and Dres to pay them the sum of P2,000 for the buildings, or sell to them the residential lot forP45; or (c) a rehearing of the case for a determination of the rights of the parties upon failure of extra-judicial settlement. The Supreme Court set aside the writ of execution issued by Judge Natividad and ordered the lower court to hold a hearing in the principal case wherein it must determine the prices of the buildings and of the residential lot where they are erected, as well as the period of time within which Hilario and Dres may exercise their option either to pay for the buildings or to sell their land, and, in the last instance, the period of time within which the Ignacios may pay for the land, all these periods to be counted from the date the judgment becomes executory or un appealable. After such hearing, the court shall render a final judgment according to the evidence presented by the parties; with costs against Hilarion and Dres. 1. Right of retention of builder in good faith The owner of the building erected in good faith on a land owned by another, is entitled to retain the possession of the land until he is paid the value of his building, under article 453. Article 453 provides that Necessary expenses shall be refunded to every possessor; buto nly the possessor in good faith may retain the thing until such expenses are made good to him. Useful expenses shall be refunded o the possessor in good faith with the same right of retention, the person who has defeated him in the possession having the option of refunding the amount of the expenses or paying the increase in value which the thing may have acquired in consequence thereof." 2. Option of the landowner to pay for the building or sell his land to the owner of the building; Right of remotion only available if he chose the latter and the owner of the building cannot pay. The owner of the land, upon the other hand, has the option, undera rticle 361, either to pay for the building or to sell his land to the owner of the building. Article 361 provides that The owner of land on which anything has been built, sown or planted in good faith, shall have the right to appropriate as his own the work, sowing or planting, after the payment of the indemnity stated in articles 453and 454, or to oblige the one who built or planted to pay the price of the land, and the one who sowed, the proper rent. He cannot however refuse both to pay for the building and to sell the land and compel the owner of the building to remove it from the land where it is erected. He is entitled to such remotion only when, after having chosen to sell his land, the other party fails to pay for the same.

3. Order amends judgment substantially and thus null and void The order of Judge Natividad compelling the Ignacios to remove their buildings from the land belonging to Hilario and Dres only becauset he latter chose neither to pay for such buildings nor to sell the land ,is null and void, for it amends substantially the judgment sought to be executed and is, furthermore, offensive to articles 361 and 453 of the Civil Code. 4. Original decision did not become final as it failed to determine the value of the buildings and of the lot; and the time to which the option may be exercised In the decision of Judge Felix, the rights of both parties were well defined under articles 361 and 453 of the Civil Code, but it failed to determine the value of the buildings and of the lot where they are erected as well as the periods of time within which the option maybe exercised and payment should be made, these particulars having been left for determination apparently after the judgment has become final. The procedure is erroneous, for after the judgment has become final, no additions can be made thereto and nothing can bed one therewith except its execution. And execution cannot be had, the sheriff being ignorant as to how, for how much, and within what time may the option be exercised, and certainty no authority is vested in him to settle these matters which involve exercise of judicial discretion. Thus, the judgment rendered by Judge Felix has never become final, it having left matters to be settled for its completion in a subsequent proceeding, matters which remained unsettled up to the time the petition is filed in the present case SARMIENTO V. AGANA129 SCRA 122 FACTS: While Ernesto Valentino was still courting his wife, latters mother offered a lot for the construction of house by the spouses. It was assumed that the wifes mother was the owner of the land, which would eventually transfer to the spouses. It turned out that Sarmiento was the owner of the land. Sarmiento filed an ejectment suit to which the trial court found out that the spouses are possessors in good faith and ordered Sarmiento to exercise option based on Art 448. Sarmiento did not exercise any of the options. The spouses then consigned the amount in court. ISSUE: Whether or not Sarmiento can refuse to exercise the given options HELD: Negative. The landowner cannot refuse both to appropriate or sell the land, and to compel the builder to remove it from the land on which it is located. He is entitled to such demolition only when after having chosen to sell the land, the other party fails to pay for the same DEPRA V. DUMLAO 136 SCRA 475 FACTS: Francisco Depra, is the owner of a parcel of land registered, situated in the municipality of Dumangas, Iloilo. Agustin Dumlao, defendant-appellant, owns an adjoining lot. When DUMLAO constructed his house on his lot, the kitchen thereof had encroached on an area of thirty four (34) square meters of DEPRAs property, After the encroachment was discovered in a relocation survey of DEPRAs lot made on November 2,1972, his mother, Beatriz Depra after writing a demand letter asking DUMLAO to move back from his encroachment, filed an action for Unlawful Detainer. Said complaint was later amended to include DEPRA as a party plaintiff. After trial, the Municipal Court found that DUMLAO was a builder in good faith, and applying

Article 448 of the Civil Code. DEPRA did not accept payment of rentals so that DUMLAO deposited such rentals with the Municipal Court. In this case, the Municipal Court, acted without jurisdiction, its Decision was null and void and cannot operate as res judicata to the subject complaint for Queting of Title. The court conceded in the MCs decision that Dumlao is a builder in good faith. Held: Owner of the land on which improvement was built by another in good faith is entitled to removal of improvement only after landowner has opted to sell the land and the builder refused to pay for the same. Res judicata doesnt apply wherein the first case was for ejectment and the other was for quieting of title. ART. 448. The owner of the land on which anything has been built sown or planted in good faith, shall have the right to appropriate as his own the works, sowing or planting, after payment of the indemnity provided for in articles 546 and 548, or to oblige the one who built or planted to pay the price of the land, and the one who sowed, the proper rent. However, the builder or planter cannot be obliged to buy the land if its value is considerably more than that of the building or trees. In such case, he shall pay reasonable rent, if the owner of the land does not choose to appropriate the building or trees after proper indemnity. The parties shall agree upon the terms of the lease and in case of disagreement, the court shall fix the terms thereof. Pursuant to the foregoing provision, DEPRA has the option either to pay for the encroaching part of DUMLAO's kitchen, or to sell th eencroached 34 square meters of his lot to DUMLAO. He cannot refuse to pay for the encroaching part of the building, and to sell the encroached part of his land, 5 as he had manifested before the Municipal Court. But that manifestation is not binding because it was made in a void proceeding. However, the good faith of DUMLAO is part of the Stipulation of Facts in the Court of First Instance. It was thus error for the Trial Court to have ruled that DEPRA is "entitled to possession," without more, of the disputed portion implying thereby that he is entitled to have the kitchen removed. He is entitled to such removal only when, after having chosen to sell his encroached land, DUMLAO fails to pay forthe same. 6 In this case, DUMLAO had expressed his willingness to pay for the land, but DEPRA refused to sell TECHNOGAS PHILIPPINES vs. CAG.R. No. 108894 February 10, 1997PANGANIBAN, J.: FACTS: The parties in this case are owners of adjoining lots in Paraaque, Metro Manila. It was discovered in a survey, that a portion of a building of Technogas, which was presumably constructed by its predecessor-in-interest, encroached on a portion of the lot owned by private respondent Edward Uy. Upon learning of the encroachment or occupation by its buildings and wall of a portion of private respondents land, the petitioner offered to buy from defendant that particular portion of Uys land occupied by portions of its buildings and wall with an area of 770square meters, more or less, but the latter, however, refused the offer

The parties entered into a private agreement before a certain Col. Rosales in Malacaang, wherein petitioner agreed to demolish th ewall at the back portion of its land thus giving to the private respondent possession of a portion of his land previously enclosed by petitioner's wall. Uy later filed a complaint before the office of Municipal Engineer of P a r a a q u e , M e t r o M a n i l a a s w e l l a s b e f o r e t h e O f f i c e o f t h e Provincial Fiscal of Rizal against Technogas in connection with the encroachment or occupation by plaintiff's buildings and walls of a portion of its land but said complaint did not prosper; so Uy dugor caused to be dug a canal along Technogas wall, a portion of w h i c h c o l l a p s e d i n J u n e , 1 9 8 0 , a n d l e d t o t h e f i l i n g b y t h e petitioner of the supplemental complaint in the above-entitled case and a separate criminal complaint for malicious mischief a g a i n s t U y a n d h i s w i f e w h i c h u l t i m a t e l y r e s u l t e d i n t o t h e conviction in court Uy's wife for the crime of malicious mischief; ISSUE: WON the petitioner is builder in good faith. HELD: YES. We disagree with Respondent Courts reliance on the cases of JM Tuason & Co Inc vs Vda de Lumanlan and JM Tuason & Co Inc vs Macalindong in ruling that the petitioner "cannot be considered in good faith" because as a land owner, it is "presumed to know the metes and bounds of his own property, specially if the same are reflected in a properly issued certificate of title. One who erroneously builds on the adjoining lot should be considered a builder in (b)ad (f)aith, there being presumptive knowledge of the Torrens title, the area, and the extent of the boundaries." There is nothing in those cases which would suggest that bad faith is imputable to a registered owner of land when a part of his building e n c r o a c h e s u p o n a n e i g h b o r ' s l a n d , s i m p l y b e c a u s e h e i s supposedly presumed to know the boundaries of his land as described in his certificate of title, Article 527 of the Civil Code presumes good faith, and since no p r o o f e x i s t s t o s h o w t h a t t h e e n c r o a c h m e n t o v e r a n a r r o w , needle-shaped portion of private respondent's land was done in bad faith by the builder of the encroaching structures, the latter s h o u l d b e p r e s u m e d t o h a v e b u i l t t h e m i n g o o d f a i t h . I t i s presumed that possession continues to be enjoyed in the same character in which it was acquired, until the contrary is proved. Good faith consists in the belief of the builder that the land he is building on is his, and his ignorance of any defect or flaw in his t i t l e . H e n c e , s u c h g o o d f a i t h , b y l a w , p a s s e d o n t o P a r i z ' s successor, petitioner in this case. The good faith ceases from the moment defects in the title are made known to the possessor, by extraneous evidence or by suit for recovery of the property by the true owner. Consequently, the builder, if sued by the aggrieved landowner for recovery of possession, could have invoked the provisions of Art.448 of the Civil Code, which reads: The owner of the land on which anything has been built, sown or planted in good faith, shall have the right to appropriate as his own the works, sowing or planting, after payment of the indemnity provided for in articles546 and 548, or to oblige the one who built or planted to pay the price of the land, and the one who sowed, the proper rent. However,

the builder or planter cannot be obliged to buy the land if its value is considerably more than that of the building or trees. In such case, he shall pay reasonable rent, if the owner of the land does not choose to appropriate the building or trees after proper indemnity. The parties shall agree upon the terms of the lease and in case of disagreement, the court shall fix the terms thereof. The obvious benefit to the builder under this article is that, instead of being out rightly ejected from the land, he can compel the landowner to make a choice between the two options: (1) to appropriate the building by paying the indemnity required by law, or (2) sell the land to the builder. The landowner cannot refuse toe x e r c i s e e i t h e r o p t i o n a n d c o m p e l i n s t e a d t h e o w n e r o f t h e building to remove it from the land I n v i e w o f t h e g o o d f a i t h o both petitioner and private respondent, their rights and obligations are to be governed by Art.448. Hence, his options are limited to: (1) appropriating the encroaching portion of petitioner's building after payment of proper indemnity, or (2) obliging the latter to buy the lot occupied by the structure. He cannot exercise a remedy of his own liking

You might also like

- Chemist Direct and CrossDocument6 pagesChemist Direct and CrossAljeane Torres100% (1)

- Sample Co-Ownership AgreementDocument5 pagesSample Co-Ownership AgreementKring de VeraNo ratings yet

- Landlord Tenant HandbookDocument63 pagesLandlord Tenant Handbookrabbi_josiah100% (2)

- Right of Accession DigestDocument23 pagesRight of Accession DigestErika Mariz Sicat CunananNo ratings yet

- Session 3 Villanueva Case - Communities Cagayan, IncDocument22 pagesSession 3 Villanueva Case - Communities Cagayan, IncKim Muzika PerezNo ratings yet

- Mario Titong Vs CA, Victorio Laurio and Angeles Laurio Court of AppealsDocument3 pagesMario Titong Vs CA, Victorio Laurio and Angeles Laurio Court of AppealsdaryllNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Olviga v. Court of AppealsDocument7 pagesHeirs of Olviga v. Court of Appealsred gynNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. L-28379 March 27, 1929 The Government of The Philippine Islands, ApplicantDocument6 pagesG.R. No. L-28379 March 27, 1929 The Government of The Philippine Islands, Applicantbbbmmm123No ratings yet

- Bernardo v. BataclanDocument1 pageBernardo v. BataclanNamiel Maverick D. BalinaNo ratings yet

- Navy Officers' Village Association, Inc. (NOVAI) vs. RepublicDocument1 pageNavy Officers' Village Association, Inc. (NOVAI) vs. RepublicRyoNo ratings yet

- Ortiz Vs Kayanan DIGESTDocument1 pageOrtiz Vs Kayanan DIGESTGeorge PandaNo ratings yet

- Case Digests For Easement (1, 12, 23)Document4 pagesCase Digests For Easement (1, 12, 23)Apay GrajoNo ratings yet

- El Banco Espanol V PetersonDocument4 pagesEl Banco Espanol V PetersongabbyborNo ratings yet

- Villa Rey Transit Vs FererDocument2 pagesVilla Rey Transit Vs Ferersarah abutazilNo ratings yet

- 1 Government Vs Cabangis 53 Phil 112Document2 pages1 Government Vs Cabangis 53 Phil 112Val SanchezNo ratings yet

- #2 Bachrach vs. Talisay-SilayDocument1 page#2 Bachrach vs. Talisay-Silaykumiko sakamoto100% (1)

- 41) Depra V DumlaoDocument1 page41) Depra V DumlaoTetel GuillermoNo ratings yet

- Melencio vs. Dy Tiao Lay PDFDocument16 pagesMelencio vs. Dy Tiao Lay PDFAira Mae P. LayloNo ratings yet

- Reyes Vs DimagibaDocument4 pagesReyes Vs DimagibaJerommel GabrielNo ratings yet

- 42 Ignacio Vs HilarioDocument3 pages42 Ignacio Vs HilarioCharm Divina LascotaNo ratings yet

- Ballatan V CADocument1 pageBallatan V CAbusinessmanNo ratings yet

- Ignacio V HilarioDocument1 pageIgnacio V HilarioVal SanchezNo ratings yet

- Possession Case DigestDocument43 pagesPossession Case DigestRUBY JAN CASAS100% (1)

- Pingol V CADocument5 pagesPingol V CAFra SantosNo ratings yet

- 11 Bachrach V SiefertDocument1 page11 Bachrach V SiefertVal SanchezNo ratings yet

- Roman V GrimaltDocument2 pagesRoman V GrimaltClarence ProtacioNo ratings yet

- Ortiz Vs KayananDocument2 pagesOrtiz Vs Kayanankumiko sakamotoNo ratings yet

- 2019-10-12 Property Law Case Digest - 1Document79 pages2019-10-12 Property Law Case Digest - 1Mik ZeidNo ratings yet

- Johannes Schuback & Sons PhilDocument11 pagesJohannes Schuback & Sons PhilGeraldine Gallaron - CasipongNo ratings yet

- Bernardo V Bataclan 1938 - Property DigestDocument1 pageBernardo V Bataclan 1938 - Property DigestNHY100% (1)

- Vda de Albar V FabieDocument3 pagesVda de Albar V Fabiejames zaraNo ratings yet

- Geminiano Vs Court of AppealsDocument3 pagesGeminiano Vs Court of AppealsPaola EscobarNo ratings yet

- Property Case Digest - PossessionDocument2 pagesProperty Case Digest - PossessionmonjekatreenaNo ratings yet

- Mindanao Bus Co. vs. City AssessorDocument6 pagesMindanao Bus Co. vs. City Assessorred gynNo ratings yet

- CITES Briefing NotesDocument3 pagesCITES Briefing NotescamilleteruelNo ratings yet

- Sy-Quia-Case BriefDocument2 pagesSy-Quia-Case BriefKatrina FregillanaNo ratings yet

- 17 Santos Vs NLRCDocument4 pages17 Santos Vs NLRCImariNo ratings yet

- Dumo Vs Republic of The PhilippinesDocument68 pagesDumo Vs Republic of The PhilippinesLawschoolNo ratings yet

- Cuayong vs. Benedicto, 37 Phil 781 - DigestDocument2 pagesCuayong vs. Benedicto, 37 Phil 781 - DigestNympa Villanueva100% (1)

- University of The Philippines College of Law: Cebu Oxygen v. BercillesDocument2 pagesUniversity of The Philippines College of Law: Cebu Oxygen v. BercillesJuno GeronimoNo ratings yet

- Cebu Oxygen v. BercillesDocument1 pageCebu Oxygen v. BercillesMariano RentomesNo ratings yet

- Naval V CaDocument2 pagesNaval V CaLawstudentArellanoNo ratings yet

- Imson vs. CaDocument10 pagesImson vs. CaAsHervea AbanteNo ratings yet

- Caltex Vs CbaaDocument2 pagesCaltex Vs CbaaCarlyn Belle de GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Tumalad vs. Vicencio, 41 SCRA 143Document6 pagesTumalad vs. Vicencio, 41 SCRA 143Reny Marionelle BayaniNo ratings yet

- Tuason Vs TuasonDocument1 pageTuason Vs TuasonPB AlyNo ratings yet

- Mangahas Vs CA CASE DIGESTDocument1 pageMangahas Vs CA CASE DIGESTChingkay Valente - JimenezNo ratings yet

- 7 Gannapao v. CSCDocument2 pages7 Gannapao v. CSCloschudentNo ratings yet

- Sarmiento Vs Agana Proerty DigestDocument2 pagesSarmiento Vs Agana Proerty DigestJener James100% (2)

- #1 Pamplona V Moreto FactsDocument11 pages#1 Pamplona V Moreto FactsDanica Irish RevillaNo ratings yet

- Enedina Presley vs. Bel-Air Village Association: GrasyaDocument13 pagesEnedina Presley vs. Bel-Air Village Association: Grasyamz rphNo ratings yet

- Co Ownership DigestsDocument4 pagesCo Ownership DigestsSusan MalubagNo ratings yet

- Caltex VC CbaaDocument2 pagesCaltex VC CbaaPatrick TanNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Tappa v. Heirs of Bacud,: HeldDocument24 pagesHeirs of Tappa v. Heirs of Bacud,: HeldMark Hiro NakagawaNo ratings yet

- Crismina Garments V CA (RM)Document2 pagesCrismina Garments V CA (RM)Pauline TuazonNo ratings yet

- Inter-Orient v. NLRCDocument4 pagesInter-Orient v. NLRCMay ChanNo ratings yet

- Pichay Vs QuerolDocument2 pagesPichay Vs QuerolriajuloNo ratings yet

- Filipinas Colleges Vs Timbang-DigestDocument2 pagesFilipinas Colleges Vs Timbang-DigestKarissa TolentinoNo ratings yet

- 1carquelo Omandam and Rosito Itom VsDocument5 pages1carquelo Omandam and Rosito Itom VsSittie Rainnie BaudNo ratings yet

- 03 Salas Vs JarencioDocument3 pages03 Salas Vs JarencioMelody May Omelan ArguellesNo ratings yet

- July 4 Prop DigestsDocument12 pagesJuly 4 Prop DigestsvalkyriorNo ratings yet

- All For Jesus Propertycases Accession: Imperial, JDocument24 pagesAll For Jesus Propertycases Accession: Imperial, JClaire RoxasNo ratings yet

- Ortiz vs. Kayanan, 92 SCRA 146Document5 pagesOrtiz vs. Kayanan, 92 SCRA 146Maria Michelle MoracaNo ratings yet

- Post Employment DigestsDocument30 pagesPost Employment DigestsAljeane TorresNo ratings yet

- Karen - Case Digest EvidenceDocument11 pagesKaren - Case Digest EvidenceAljeane TorresNo ratings yet

- MCC MinutesDocument3 pagesMCC MinutesAljeane TorresNo ratings yet

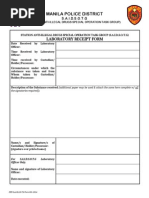

- Manila Police District: Laboratory Receipt FormDocument1 pageManila Police District: Laboratory Receipt FormAljeane TorresNo ratings yet

- Pintl Case Digest 1Document6 pagesPintl Case Digest 1Saline EscobarNo ratings yet

- Memo ReconstitutionDocument5 pagesMemo ReconstitutionAljeane TorresNo ratings yet

- Take Care My Bus LyricsDocument4 pagesTake Care My Bus LyricsAljeane TorresNo ratings yet

- Plain ViewDocument2 pagesPlain ViewAljeane TorresNo ratings yet

- Envelope DesignDocument1 pageEnvelope DesignAljeane TorresNo ratings yet

- Baguinat BriefDocument6 pagesBaguinat BriefAljeane TorresNo ratings yet

- Alteration of Land AreaDocument6 pagesAlteration of Land AreaAljeane TorresNo ratings yet

- Training Road Map: Department: Procurement Office Division: Procurement GroupDocument3 pagesTraining Road Map: Department: Procurement Office Division: Procurement GroupAljeane TorresNo ratings yet

- RA 6716 Rainwater CollectionDocument15 pagesRA 6716 Rainwater CollectionAljeane Torres100% (1)

- JURIS Qualified RapeDocument10 pagesJURIS Qualified RapeAljeane TorresNo ratings yet

- Final People v. TanDocument12 pagesFinal People v. TanAljeane TorresNo ratings yet

- Last Will and TestamentDocument18 pagesLast Will and TestamentAljeane Torres100% (1)

- CK-MMD-10 AccreditationDocument2 pagesCK-MMD-10 AccreditationChrister Glenn DequitosNo ratings yet

- De Ocampo v. RPN-9Document6 pagesDe Ocampo v. RPN-9Janelle Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Federal Complaint For Intervention Into Lawsuit To Collect MoneyDocument40 pagesFederal Complaint For Intervention Into Lawsuit To Collect MoneyJeff NewtonNo ratings yet

- Absolute Community Vs ConjugalDocument6 pagesAbsolute Community Vs ConjugalSERVICES SUBNo ratings yet

- Draft WillDocument5 pagesDraft WillShubha PujariNo ratings yet

- Philippine National Bank v. Mallorca Case DigestDocument2 pagesPhilippine National Bank v. Mallorca Case DigestMarionnie Sabado50% (2)

- M T Ngày Không Mưa - (Tab by Haketu)Document2 pagesM T Ngày Không Mưa - (Tab by Haketu)Phuc DaNo ratings yet

- Template of Letter To Claim Back Bank Charges VictoriaDocument2 pagesTemplate of Letter To Claim Back Bank Charges VictoriaGabriel Inya-AghaNo ratings yet

- Zeal Institute of Management and Computer ApplicationDocument4 pagesZeal Institute of Management and Computer ApplicationVandana JagtapNo ratings yet

- Module 4 Composition of Gross EstateDocument3 pagesModule 4 Composition of Gross EstateLyre LevierNo ratings yet

- IEEE Guide For Power System Protection TestingDocument135 pagesIEEE Guide For Power System Protection TestingHugo EscobarNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court: General Joins Her in Her Plea, Hence We Required The NLRC To File Its Own CommentDocument3 pagesSupreme Court: General Joins Her in Her Plea, Hence We Required The NLRC To File Its Own CommentduskwitchNo ratings yet

- Post JudgmentDocument28 pagesPost JudgmentstitesattorneyNo ratings yet

- Taxi Drivers File Suit Against City of SeattleDocument8 pagesTaxi Drivers File Suit Against City of SeattleTaylor SoperNo ratings yet

- Dominion Insurance v. CADocument1 pageDominion Insurance v. CARostum AgapitoNo ratings yet

- Register of LogoDocument6 pagesRegister of LogoOPPTIN100% (2)

- Eastern Shipping Lines, Inc. Vs IACDocument15 pagesEastern Shipping Lines, Inc. Vs IACDarwin SolanoyNo ratings yet

- Punjab Land Revenue Act, 1967Document18 pagesPunjab Land Revenue Act, 1967Muhammad ShahzadNo ratings yet

- Human Geography Places and Regions in Global Context Updated Fifth 5th Canadian Edition by Paul L. Knox Wei Zhi All Chapters Instant DownloadDocument33 pagesHuman Geography Places and Regions in Global Context Updated Fifth 5th Canadian Edition by Paul L. Knox Wei Zhi All Chapters Instant Downloadtitetalak100% (1)

- Foodsphere Vs MauricioDocument2 pagesFoodsphere Vs MauricioQuennieNo ratings yet

- IEEE STD 1138-2009Document14 pagesIEEE STD 1138-2009NataGB100% (1)

- Dorman v. PACCAR - Order Granting StayDocument6 pagesDorman v. PACCAR - Order Granting StaySarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Criminal Procedure Code2Document2 pagesCriminal Procedure Code2threwawayNo ratings yet

- Customer Request Form BDocument1 pageCustomer Request Form BALIASGER ABIDBHAI RANGWALANo ratings yet

- Question Answer Negotiable Instrument LawDocument4 pagesQuestion Answer Negotiable Instrument LawEuxine Albis0% (2)

- Request For Proposal (RFP) #4794 Physiotherapy Services: Sponsored by Health PEI - Community Hospitals WestDocument29 pagesRequest For Proposal (RFP) #4794 Physiotherapy Services: Sponsored by Health PEI - Community Hospitals WestDiganta DasNo ratings yet

- ALI Abes Notice of Lis PendensDocument2 pagesALI Abes Notice of Lis PendensKaiNo ratings yet

- Seminold OCCC Teen Drive Summit PrintDocument1 pageSeminold OCCC Teen Drive Summit PrintPrice LangNo ratings yet