What Is Dehydration

What Is Dehydration

Uploaded by

Marwan WijayaCopyright:

Available Formats

What Is Dehydration

What Is Dehydration

Uploaded by

Marwan WijayaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

What Is Dehydration

What Is Dehydration

Uploaded by

Marwan WijayaCopyright:

Available Formats

What is dehydration?

The majority of the body is made up of water, with up to 75% of the body's weight due to H2O. Most of the water is found within the cells of the body (intracellular space). The rest is found in what is referred to as the extracellular space, which consists of the blood vessels (intravascular space) and the spaces between cells (interstitial space). Total body water = intracellular space + intravascular space + interstitial space Dehydration occurs when the amount of water leaving the body is greater than the amount being taken in. The body is very dynamic and always changing. This is especially true with water in the body. We lose water routinely when: we breathe and humidified air leaves the body; we sweat to cool the body; and we urinate or have a bowel movement to rid the body of waste products. In a normal day, a person has to drink a significant amount of water to replace this routine loss. If intravascular (within the blood vessels) water is lost, the body can compensate somewhat by shifting water from cells into the blood vessels, but this is a very short-term solution. Signs and symptoms of dehydration will occur quickly if the water is not replenished. The body is able to monitor the amount of fluid it needs to function. The thirst mechanism signals the body to drink water when the body is dry. As well, hormones like anti-diuretic hormone (ADH) work with the kidney to limit the amount of water lost in the urine when the body needs to conserve water.

What causes dehydration?

Dehydration occurs because there is too much water lost, not enough water taken in, or most often a combination of the two. Diarrhea: Diarrhea is the most common reason a person loses excess water. A significant amount of water can be lost with each bowel movement. Worldwide, more than four million children die each year because of dehydration from diarrhea. Vomiting: Vomiting can also be a cause of fluid loss and it is difficult for a person to replace water by drinking it if they are unable to tolerate liquids. Sweat: The body can lose significant amounts of water when it tries to cool itself by sweating. Whether the body is hot because of the environment (for example, working in a warm environment), intense exercising in a hot environment, or because a fever is present due to an infection; the body uses a significant amount of water in the form of sweat to cool itself. Depending upon weather conditions, a brisk walk will generate up to 16 ounces of sweat (a pound of water). Diabetes: In people with diabetes, elevated blood sugar levels cause sugar to spill into the urine and water then follows, which can cause significant dehydration. For this reason, frequent urination and excessive thirst are among the symptoms of diabetes. Burns: Burn victims become dehydrated because water seeps into the damaged skin. Other inflammatory diseases of the skin are also associated with fluid loss. Inability to drink fluids: The inability to drink adequately is the other potential cause of dehydration. Whether it is the lack of availability of water or the lack of strength to drink adequate amounts, this, coupled with routine or extraordinary water losses can compound the degree of dehydration.

What are the signs and symptoms of dehydration?

The body's initial responses to dehydration are thirst to increase water intake along with decreased urine output to try to conserve water. The urine will become concentrated and more yellow in color. As the level of water loss increases, more symptoms can become apparent. The following are further signs and symptoms of dehydration: dry mouth, the eyes stop making tears,

sweating may stop, muscle cramps, nausea and vomiting, heart palpitations, and lightheadedness (especially when standing). The body tries to maintain cardiac output (the amount of blood that is pumped by the heart to the body); and if the amount of fluid in the intravascular space is decreased, the body has to increase the heart rate, which causes blood vessels to constrict to maintain blood pressure. This coping mechanism begins to fail as the level of dehydration increases. With severe dehydration, confusion and weakness will occur as the brain and other body organs receive less blood. Finally, coma and organ failure will occur if the dehydration remains untreated.

How is dehydration diagnosed?

Dehydration is often a clinical diagnosis. Aside from diagnosing the reason for dehydration, the health care practitioner's examination of the patient will assess the level of dehydration. Initial evaluations may include: Mental status tests to evaluate whether the patient is awake, alert, and oriented. Vital signs may include postural readings (blood pressure and pulse rate are taken lying down and standing). With dehydration, the pulse rate may increase and the blood pressure may drop because the intravascular space is depleted of water. Special consideration, many people are prescribed high blood pressure medications called beta blockers that may prevent these compensatory increases in the heart rate. Temperature may be measured to assess fever. Skin will be checked to see if sweat is present and to assess the degree of elasticity (turgor). As dehydration progresses, the skin loses its water content and becomes less elastic. Infants may have additional evaluations performed, including checking for a soft spot on the skull (sunken fontanelle), assessing the suck

mechanism, muscle tone, or loss of sweat in the armpits and groin. All are signs of potential significant dehydration. Pediatric patients are often weighed during routine child visits, thus a body weight measurement may be helpful in assessing how much water has been lost with the acute illness. Laboratory testing The purpose of blood tests is to assess potential electrolyte abnormalities (especially sodium levels) associated with the dehydration. Tests may or may not be done on the patient depending upon the underlying cause of dehydration, the severity of illness, and the health care practitioner's assessment of their needs. Urinalysis may be done to determine urine concentration - the more concentrated the urine, the more dehydrated the patient.

How is dehydration treated?

As is often the case in medicine, prevention is the important first step in the treatment of dehydration. (Please see the home treatment and prevention sections.) Fluid replacement is the treatment for dehydration. This may be attempted by replacing fluid by mouth, but if this fails, intravenous fluid (IV) may be required. Should oral rehydration be attempted, frequent small amounts of clear fluids should be used. Clear fluids include: water, clear broths, popsicles, Jell-O, and other replacement fluids that may contain electrolytes (Pedialyte, Gatorade, Powerade, etc.) Decisions about the use of intravenous fluids depend upon the healthcare provider's assessment of the extent of dehydration and the ability for the patient to recover from the underlying cause.

The success of the rehydration therapy can be monitored by urine output. When the body is dry, the kidneys try to hold on to as much fluid as possible, urine output is decreased, and the urine itself is concentrated. As treatment occurs, the kidneys sense the increased fluid and urine output increases. Medications may be used to treat underlying illnesses and to control fever, vomiting, or diarrhea.

Can I treat dehydration at home?

Dehydration occurs over time. If it can be recognized in its earliest stages, and if its cause can be addressed, then home treatment may be adequate. Steps a person can take at home to prevent severe dehydration include: Individuals with vomiting and diarrhea can try to alter their diet and use medications to control symptoms to minimize water loss. Acetaminophen or ibuprofen may be used to control fever. Fluid replacements may be attempted by replacing fluid by mouth with frequent small amounts of clear fluids (see clear fluids information in previous section). If the patient becomes confused or lethargic; if there is persistent, uncontrolled fever, vomiting, or diarrhea; or if there are any other specific concerns, then medical care should be accessed. Emergency medical system (EMS) or 911 should be activated for any individual with altered mental status - confusion, lethargy, or coma.

What are the complications of dehydration?

Complications of dehydration may occur because of the dehydration, and/or because of the underlying disease or situation that causes the fluid loss. Kidney failure Kidney failure is a common occurrence, although if it is due to dehydration and is treated early, it is often reversible. As dehydration progresses, the volume of fluid in the intravascular space decreases, and blood pressure may

fall. This can decrease blood flow to vital organs like the kidneys, and like any organ with a decreased blood flow; it has the potential to fail to do its job. Coma Decreased blood supply to the brain may cause confusion and even coma. If enough organs begin to malfunction, the body itself may fail, and death can occur. Shock When the fluid loss overwhelms the body's ability to compensate, blood pressure falls (hypotension) and the patient may go into shock, in which organs in the body may not get enough oxygen to function and thus fail. Heat-related illnesses and associated complications In heat-related illness, the body's attempt to cool itself by sweating may cause dehydration to the point that muscles may go into spasm (heat cramps). It is often the muscles that are being stressed that will spasm (for example, in people who work outside in a hot environment, ,arm and leg muscles may spasm from lifting and moving heavy objects or equipment; in athletes, leg muscles may fail from running). As fluid loss increases, the patient may be so dehydrated that there is not enough water to sweat and heat exhaustion or heat stroke may occur. Heat stroke is a true medical emergency and 911 or the Emergency Response System should be activated immediately in this situation. Electrolyte abnormalities In dehydration, electrolyte abnormalities may occur since important chemicals (like sodium and potassium) are lost from the body through sweat. For example, patients with profuse diarrhea or vomiting may lose significant amounts of potassium, causing muscle weakness and heart rhythm disturbances. The health care provider needs to be aware of the fluid and electrolyte balance in the dehydrated patient and be certain to monitor electrolyte levels as rehydration occurs. Some examples of symptoms caused by abnormal electrolyte levels include muscle weakness due to low potassium, heart rhythm disturbances due to either low or high potassium, and seizures due to low sodium. It is reasonable to remember that dehydration does not occur quickly, and sometimes it may take hours to slowly correct the fluid deficit and allow the

electrolytes to redistribute themselves appropriately in the different spaces in the body. If rehydration is done too slowly, the patient may remain hypotensive and in shock for too long. If done too quickly, water and electrolyte concentrations within organ cells can be negatively affected, causing cells to swell and eventually die.

You might also like

- Sample Discharge PlanningDocument1 pageSample Discharge Planninghalloween candy100% (2)

- The Water CureDocument27 pagesThe Water CureVijay Agrawal100% (5)

- Education MCQs From AJKPSC Past PapersDocument51 pagesEducation MCQs From AJKPSC Past PapersAroosakanwal100% (4)

- Hydration FlyerDocument2 pagesHydration FlyerKatrina Nelson100% (1)

- Gastric Outlet Obstruction, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandGastric Outlet Obstruction, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- Ventricular Septal Defect, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandVentricular Septal Defect, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- Dehydration Facts: Body Weight Daily Fluid Requirements (Approximate)Document5 pagesDehydration Facts: Body Weight Daily Fluid Requirements (Approximate)liviuNo ratings yet

- Scenario EnglishDocument10 pagesScenario EnglishAnonymous b3qYYIrQkONo ratings yet

- Dehydration: By: M. SofyanDocument2 pagesDehydration: By: M. Sofyansofyan novrizalNo ratings yet

- DehydrationDocument2 pagesDehydrationsofyan novrizalNo ratings yet

- Fluid & Electrolyte Imbalance/ DehydrationDocument7 pagesFluid & Electrolyte Imbalance/ Dehydrationneleh grayNo ratings yet

- Dehydration Research PaperDocument5 pagesDehydration Research Paperapi-399491923No ratings yet

- DehydrationDocument8 pagesDehydrationJini Donguines GulmaticoNo ratings yet

- Why Is Water ImportantDocument5 pagesWhy Is Water ImportantchapinatNo ratings yet

- DehydrationDocument8 pagesDehydrationNader SmadiNo ratings yet

- Water's Effectiveness On The BodyDocument4 pagesWater's Effectiveness On The BodyDennis MitchellNo ratings yet

- DehydrationDocument16 pagesDehydrationBenben LookitandI'mNo ratings yet

- MCN - FluidsDocument3 pagesMCN - FluidsMichiko CiriacoNo ratings yet

- Water and The Major MineralDocument7 pagesWater and The Major MineralRohmah Nur HusnahNo ratings yet

- Case Study On DehydrationDocument4 pagesCase Study On DehydrationDustin Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Dehydration by MR Wahid UllahDocument24 pagesDehydration by MR Wahid UllahWahid UllahNo ratings yet

- Shock - Specific TypesDocument8 pagesShock - Specific Typeshenryvds5554No ratings yet

- Dehydration PDFDocument3 pagesDehydration PDFnot realNo ratings yet

- Dehydration PPDocument17 pagesDehydration PPApol PenNo ratings yet

- English Carnival-Public Speaking FarrelDocument3 pagesEnglish Carnival-Public Speaking FarrelMOHAMAD FAIZ MOHAMA NOORNo ratings yet

- What Causes Dehydration? Dehydration and Acute Dehydration. Both Types of Dehydration Can Be Caused by ADocument3 pagesWhat Causes Dehydration? Dehydration and Acute Dehydration. Both Types of Dehydration Can Be Caused by AIlyes FerenczNo ratings yet

- Dehydration: 2 Signs and SymptomsDocument5 pagesDehydration: 2 Signs and SymptomsZiedTrikiNo ratings yet

- Dehydration OutlineDocument4 pagesDehydration OutlinemariusjayzafraNo ratings yet

- Dehydration OutlineDocument4 pagesDehydration OutlinemariusjayzafraNo ratings yet

- Dehydration Types Causes Symptoms and TreatmentDocument5 pagesDehydration Types Causes Symptoms and TreatmentmournamourNo ratings yet

- New StartDocument2 pagesNew StartJc LastaNo ratings yet

- Heat Cramps OverviewDocument11 pagesHeat Cramps OverviewDita AyuningtyasNo ratings yet

- Homeostasis SS2Document4 pagesHomeostasis SS2Ezeh PrincessNo ratings yet

- Analysis Physiological IndicatorsDocument8 pagesAnalysis Physiological IndicatorsTatadarz Auxtero Lagria100% (1)

- Order 241064221 - Health CareDocument8 pagesOrder 241064221 - Health CareNikka GadazaNo ratings yet

- Deficient Fluid Volume Nursing Diagnosis & Care Plan - RNlessonsDocument11 pagesDeficient Fluid Volume Nursing Diagnosis & Care Plan - RNlessonsA.No ratings yet

- Isotonic SolutionDocument12 pagesIsotonic SolutionWaleed AhmadNo ratings yet

- Science Reviewer: Endocrine System (Part 1)Document3 pagesScience Reviewer: Endocrine System (Part 1)aNo ratings yet

- Dr. F. BatmanghelidjDocument18 pagesDr. F. BatmanghelidjSilas Yenbon SebireNo ratings yet

- OsmoregulationDocument6 pagesOsmoregulationNIRBHAY_BARDIYANo ratings yet

- Fdocuments - in Kangen Water in DepthDocument25 pagesFdocuments - in Kangen Water in Depthg kumarNo ratings yet

- Change Your Water, Change Your LifeDocument25 pagesChange Your Water, Change Your LifeWim MassopNo ratings yet

- Sports Nutrition For Young Adults: HydrationDocument4 pagesSports Nutrition For Young Adults: HydrationgiannidietNo ratings yet

- Water OxygenDocument6 pagesWater Oxygenamicho2407No ratings yet

- The Ultimate Water Survival Guide: Simple Step-By-Step Manual on How to Find, Harvest, Treat and Store Water for Self-Sufficiency Off-The-GridFrom EverandThe Ultimate Water Survival Guide: Simple Step-By-Step Manual on How to Find, Harvest, Treat and Store Water for Self-Sufficiency Off-The-GridNo ratings yet

- PhysiologyDocument5 pagesPhysiologyOmar KamalNo ratings yet

- Fluid Imbalance With Constant OsmolarityDocument36 pagesFluid Imbalance With Constant OsmolarityArceo AbiGailNo ratings yet

- EdemaDocument5 pagesEdemaghica05No ratings yet

- Beware of DehydrationDocument2 pagesBeware of DehydrationFavour ChukwuelesieNo ratings yet

- What Is HypovolemiaDocument10 pagesWhat Is HypovolemiaPolly FulangenNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 NFS 301Document45 pagesChapter 3 NFS 301solaveNo ratings yet

- Fluid Volume Deficit Nursing ManagementDocument5 pagesFluid Volume Deficit Nursing ManagementA.No ratings yet

- Card 2 Sensible and Insensible Fluid LossDocument1 pageCard 2 Sensible and Insensible Fluid LossCaitlin MenziesNo ratings yet

- Water Balance7888Document2 pagesWater Balance7888Aditya Diwedi100% (1)

- Water MetabolismDocument3 pagesWater MetabolismJuber mansuriNo ratings yet

- A Simple Guide to Hypovolemia, Diagnosis, Treatment and Related ConditionsFrom EverandA Simple Guide to Hypovolemia, Diagnosis, Treatment and Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- Fluid and Electrolyte BalanceDocument52 pagesFluid and Electrolyte BalanceFrancis Appau100% (1)

- Fluid Volume Deficit (Dehydration) Nursing Care Plan - NurseslabsDocument17 pagesFluid Volume Deficit (Dehydration) Nursing Care Plan - NurseslabsA.No ratings yet

- Paraphrasing Assigments Given by Maam MasdiniDocument2 pagesParaphrasing Assigments Given by Maam Masdinirizal syiqinNo ratings yet

- SCI-241 WK 5 Assignment DehydrationDocument7 pagesSCI-241 WK 5 Assignment DehydrationAnna Shyne BorsickNo ratings yet

- Pre-Final Examination in Physical Education and HealthDocument4 pagesPre-Final Examination in Physical Education and HealthJacquilou SalalimaNo ratings yet

- This Study Resource Was: Needs Assessment Case StudyDocument7 pagesThis Study Resource Was: Needs Assessment Case StudyHugsNo ratings yet

- Naskah Soal BHS InggrisDocument13 pagesNaskah Soal BHS InggrisYanuar IhsanNo ratings yet

- Health Flow ChartDocument1 pageHealth Flow ChartAlex Cainoy JrNo ratings yet

- Exemption Application From Personal AppearanceDocument4 pagesExemption Application From Personal AppearanceAdityaNo ratings yet

- Funding Indigenous PeoplesDocument9 pagesFunding Indigenous PeoplesErna Mae AlajasNo ratings yet

- Correlation Between Dietary Habit and Nutritional Status With Mental Health Status of Elementary School StudentsDocument8 pagesCorrelation Between Dietary Habit and Nutritional Status With Mental Health Status of Elementary School StudentsSalsa EvvaNo ratings yet

- Resolution On The Appointment of Barangay Health WorkerDocument3 pagesResolution On The Appointment of Barangay Health Workerdiane SamaniegoNo ratings yet

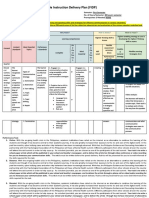

- Flexible Instruction Delivery Plan TemplateDocument4 pagesFlexible Instruction Delivery Plan TemplateLennie DiazNo ratings yet

- A Cure Is Not WelcomeDocument243 pagesA Cure Is Not WelcomeDesmond AllenNo ratings yet

- Bo de Thi Chon Hoc Sinh Gioi Mon Tieng Anh Lop 12 Tinh Thai Binh Nam 2015 2016Document23 pagesBo de Thi Chon Hoc Sinh Gioi Mon Tieng Anh Lop 12 Tinh Thai Binh Nam 2015 2016deniust121No ratings yet

- Lecture PATHFT2Document7 pagesLecture PATHFT2Gniese Stephanie Gallema AlsayNo ratings yet

- How To Become An Effective LeaderDocument15 pagesHow To Become An Effective Leadermaham farooqiNo ratings yet

- IntroductionsDocument4 pagesIntroductionssansay cagaananNo ratings yet

- Career Guide For International Students Graduate Diploma in TeachingDocument11 pagesCareer Guide For International Students Graduate Diploma in Teachingsandy mooNo ratings yet

- Mi RNADocument14 pagesMi RNATeoMartinNo ratings yet

- Appointment - First AiderDocument1 pageAppointment - First AiderJamie GovenderNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Clinical Competence and Clinical Self-Efficacy Among Nursing and Midwifery StudentsDocument8 pagesThe Relationship Between Clinical Competence and Clinical Self-Efficacy Among Nursing and Midwifery StudentsissaiahnicolleNo ratings yet

- SSM120 410007 Unit5Document41 pagesSSM120 410007 Unit5Trí Phạm MinhNo ratings yet

- Basic Practice OhsDocument165 pagesBasic Practice Ohskentcarlopaye08No ratings yet

- JBFRUIT - Co CompressedDocument3 pagesJBFRUIT - Co CompressedWijaya Kusuma SubrotoNo ratings yet

- Atlas of Robotic Urologic SurgeryDocument473 pagesAtlas of Robotic Urologic SurgerySarita Moreno SorribasNo ratings yet

- Malaria Case Management Training Manual For Health Professionals in Ethiopia Participants ManualDocument200 pagesMalaria Case Management Training Manual For Health Professionals in Ethiopia Participants ManualEleni HagosNo ratings yet

- Growth Translated FinalDocument239 pagesGrowth Translated FinalMuhammad Mudassar0% (1)

- China Rapidly Evolving Health Care System Blumenthal2015Document5 pagesChina Rapidly Evolving Health Care System Blumenthal2015PhyoNyeinChanNo ratings yet

- DDocument56 pagesDDarren Balbas100% (1)

- Eastmont ExtraDocument4 pagesEastmont ExtraScott WebsterNo ratings yet

- Performance Task (Finals) - Technical WritingDocument17 pagesPerformance Task (Finals) - Technical WritingThe Phoebie JhemNo ratings yet