(Sound Engineering) Sound Engineering and Musician Book p2

(Sound Engineering) Sound Engineering and Musician Book p2

Uploaded by

idscribdgmailCopyright:

Available Formats

(Sound Engineering) Sound Engineering and Musician Book p2

(Sound Engineering) Sound Engineering and Musician Book p2

Uploaded by

idscribdgmailOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

(Sound Engineering) Sound Engineering and Musician Book p2

(Sound Engineering) Sound Engineering and Musician Book p2

Uploaded by

idscribdgmailCopyright:

Available Formats

SOUND ENGINEERING AND MUSICIAN BOOK - PART TWO

Getting Rid Of Annoying Fret Buzz Look to the strings first. You may need to change them.

Are they accumulating a film? (You may need to look on the underside to see all the dirt you have on them.) There are a handful of products designed to extend the life of your strings, but if you want to go the economy route, simply wiping them down with a slightly damp cloth will be better than nothing. Do you see dirt and grime building up on the fret board? (Minor, but if you're cleaning for grime, you might as well clean this surface during strings changes.) You may want to clean this using a slightly damp cloth or a good guitar cleaner. Some people recommend using the finest grade of steel wool to abrade extra tough dirt off your fret board. I haven't had to go this far yet, and would urge caution to go easy on the elbow grease as to not scratch the finish on the wood. Long sweat and dirt buildup can eventually damage glue joints and warp your instrument (this would be after a long period of exposure without any maintenance). I'm by no means an avid "guitar-polishing guy" but the occasional cleaning of the fret board will extend its life.

If this doesn't fix your problem, the solution may require the expertise of an experienced technician. There are some things you should do to pinpoint the location of your buzz, but I'd never recommend someone grab their tools and try to adjust a guitar on their own. Learn from someone with experience and your guitar won't become a field casualty. Check to see if the buzz is consistent across the length of the neck (from open strings to the frets with small spacing towards the body of the instrument).

Pick each string without fretting any notes. Fret each string at the first fret and move towards the body. You may not need to successively fret each position, but if you're compulsive about your instrument Make a note as to where the buzz appears and where is goes away. If the buzz stays from the open strings and doesn't go away even when you're fretting the highest pitched frets, the problem is likely in your bridge/saddle assembly. Are there any loose parts? You may need to have a technician work on this area. See if they'll let you view the process. I've gleaned a lot of maintenance knowledge by being present and asking simple question while someone worked on my instruments. (Don't get in the way, technicians will tolerate your presence and questions, if they aren't annoyed by you're being there) You may need to have your strings saddles adjusted up so they will be farther away from the first frets they come across. If you do this yourself, try to

If you pinpoint the buzzing to the section of your neck closer to the body:

make your adjustments in slight increments so you don't raise your action more than you need to. If the height of the saddle won't compensate enough, a truss rod adjustment is probably needed (see below).

There may be a fret, which needs to be sanded slightly to eliminate an inconsistent span. Don't make this adjustment yourself. If you go too far, the mutilated fret will become permanently sharp in pitch. Inserting a slight shim under the nut can raise the strings high enough to eliminate the strings unwelcome contact with the frets. This might be difficult if you have a glued in nutbut those of you who put up with the locking variety, can easily take the nut off and insert a small piece of paper or foil under the nut. Remember to take it in increments; it's hard to play those neoclassical licks with high action. Your neck may need to have the truss rod adjusted. This is a rod of metal, which runs the length of your guitar neck. By turning it to the left or right, you cause the wood to bow in or out. Of all the adjustments mentioned, this is the most dangerous and should definitely be handled by a technician. If you turn the rod too far (as in of a turn) you can splinter the neck. Here is a step to watch and learn. Minute adjustments can make a big difference in the bow of the neck.

If the buzzing is closer to the middle of the neck or towards the nut:

Some adjustments may cause other adjustments to be needed to preserve the action by the way. Cleaning the neck and getting a new set of strings might solve your problems. If you're a strummer and using light strings, maybe you should raise the action and move up to a heavier gauge of string. Don't be afraid to take your instrument to a technician. You can learn quite a bit for future maintenance. What are the differences between Gain, Overdrive and Distortion? Using Gain, Overdrive, and Distortion can either add or detract from your overall guitar tone, so it's a good idea to know the differences between them. Technically speaking, There are several definitions to these terms, but we are only going to deal with the audio Aspects, or how it sounds to your ears. Gain is usually defined as an overall boost in your signal without any added tonal coloration. It is usually expressed in decibels such as "Gimme a 3dB boost on that kick drum." Adding more gain is basically just amplifying the signal so it cut through the mix or can be heard over a loud drummer. Overdrive, as it has come to be known as, is a smooth, warm, slightly distorted sound, generally associated with the sound made by cranking up a tube amp. It is fat and dynamic, allowing you to vary your tone just by the way you play. Overdrive pedals can come close to giving you that tube overdrive sound, probably the most popular being the Tube Screamer. Distortion can be defined as anything from a fuzz tone to a full-on, notched-out midrange, death metal wall of noise. It is a hard-edged sound with as many variations as there are players. Digital distortion has a more metallic, raspy sound which works well for heavy metal, grunge, or reliving your 80's hair band days. Analog tube distortion gives a good, all-around rock tone, such as the sound of a Marshall stack cranked to 10. The key to all this is to listen and experiment and let your ears be the final judge.

Knowing the differences and how to use them will go a long way to helping you define your own signature tone. Optimizing Guitar Playability Playing guitar is a highly personal experience. Every player has different needs, and that is why setting up your new guitar becomes a matter of personal taste. We generally recommend taking your new ax to a qualified luthier for a proper set-up. Although most guitars play great right out of the box, some need just a little bit of tweaking to make them really perform. Ultimately what you are trying to achieve is: 1. Good Action (the least possible distance between the string and the frets without buzzing or rattling of the string against the fret). 2. Balanced, even, electrical output on each string in all pickup positions. 3. Smooth, accurate tuning action and the ability to stay in tune after bending a note or using the tremolo. 4. Last, but certainly not least, killer Tone! Keep in mind though, that some of these goals are mutually incompatible. For instance, really light strings and really low action don't allow a guitar to sustain or sound fat, compared to the same guitar with heavier strings and higher action. Finding that optimal playing "zone" is sometimes a matter of compromise. Knowing that, here are some tips that can help you achieve guitar nirvana. Strings: Experimenting with different brands is great, but once you a find a brand and gauge you like, stick with it. Your guitar will thank you for it. Constantly changing string gauges usually involves adjustments to the neck, which can be a time-consuming pain, and wouldn't you rather be playing? Wiping your strings down with a clean cloth after playing can extend their life and your wallet. If you are breaking alot of strings at the bridge, the most likely cause are burrs that develop on the string saddles. A light sanding and polishing is all that is needed to smooth these out. Take your guitar to a luthier if you don't feel comfortable doing this yourself. Tuners: I can't say enough good things about Sperzel locking tuners. They are worth their weight in gold. While I wouldn't recommend installing them on a vintage Strat; for a new, out-of-the-box guitar they work wonders. They offer rock solid tuning, and actually improve sustain by adding more mass to the headstock. If you're going with stock tuners, make sure all screws are snug but not too tight. If it still feels sloppy or will not hold the pitch, replace them. Pickups: There is a phenomenon regarding guitar pickups called "magnetic interferance." This is where the magnetic field generated by the pickup actually impedes the vibration of the string, causing a dull, lifeless sound. Generally you want to get the pickups close enough for good output, but not so close as to choke the string. Fender recommends around 5/64" clearance from the top of the pole piece to the bottom of the string fretted at the last fret. You can check this with ]automotive type feeler gauges.

Action: This is going to be a general recommendation which may not apply to everyone's playing style. First, check the relief, or amount of bow in the neck. Put a capo at the first fret then hold down the 6th string at the last fret. Using a feeler gauge, measure the gap between the string and the 8th fret. Factory spec for Strats and clones should be around .010" Next, check the bridge saddle height. Factory spec at the 17th fret should be 5/65" for strings 1-4, 3/32" for strings 5-6. Another really cool trick is to adjust the saddles to follow the radius of the fingerboard, meaning the middle string saddlesare higher than the outside saddles. This allows the strings to follow the natural curve of the fingerboard and makes for a smoother playing neck. These are just a few recommendations for getting the most out of your guitar. Again, if you don't feel comfortable with doing this yourself, take it to your favorite luthier. Watch and learn, and pretty soon you'll be doing it yourself. Also, if your'e a do-ityourself kind of person, pick up a copy of The "Guitar Player's Repair Guide." It too is worth its weight in gold. Drum Set Assembly 101 Now that Christmas is over and the bicycles have been put together, the new clothes have all been worn and the chocolate covered cherries have been eaten, it's time to put together the drum kit you bought for Junior. Getting familiar with the kit There are many different drum set combinations, the most common being the 5piece kit. We will be assembling a kit consisting of these shell components: 1 1 1 1 1 16" x 22" Bass Drum 10" x 12" Ride Tom 11" x 13" Ride Tom 16" x 16" Floor Tom 5.5" x 14" Snare Drum

And these hardware components: 1 - Bass Drum Pedal 1 - Snare Drum Stand 1 - Hi-Hat Stand 2 - Tom Holders 3 - Floor Tom Legs 2 - Cymbal stands (one straight and one boom) Let's Begin: Start with the bass drum. Locate the bass drum hoops, which are the largest of the hoops, and are usually the same color as the drum kit. You will also need to find the hoop claws and the longest lugs in the bag of misc. hardware you will receive with the kit. You should have 16 of each (8 for each hoop). Set the bass drum so it is flat on the floor. A determination will need to be made as to which is the front head and which is the "batter side" head. With most drum kits you will have the manufacture's logo on one of the heads, which goes on the front of the drum. Determining the front of the bass drum is much easier. The side closest to the bass drum legs (or spurs) is the front. Place one of the small washers on each of the long lugs and insert through the hole in the claw. They will only work one way, so try one before you put them all together.

There are usually 8 lugs per side, so place the correct head on the drum, place the hoop on the head (it should fit on the outer rim of the head) and hang the claws on the hoop, threading them into the bridge lugs on the drum. Finger-tighten the head, turn the bass drum over and repeat. NOTE: often times a small pillow placed in the bass drum removes over-ring and adds punch. Next the Toms. Locate the smallest of the toms and find the 2 heads and 2 chrome hoops that are the same size. There will also be 12 short lugs and 12 washers necessary for this drum kit. Place the head on the drum and the hoop on the head lining up the holes in the hoop with the bridge lugs on the drum. Place a washer on each lug and insert through the hole, and thread into the bridge lugs. Finger tighten only. Turn drum over and repeat. Note: Sometimes a top and bottom (batter head and bottom head) will be sent. The bottom head will always be thinner, usually transparent. Using the same technique to do the other ride tom and floor tom, we should have all of the drums with heads. If the snare drum is not assembled, use the same technique for it as well. Let's put it all together Again let's start with the bass drum. Set the drum so that the 2 spurs are close to the ground, and the chrome mount located near the middle of the drum is pointing up. Set the legs so that they are holding the bass drum securely, and not able to rock sideways (as if rolling). Firmly tighten the spurs. Find the 2 tom holders in the package of tubular hardware. Each of these should fit into one of the holes in the top of the bass drum. Insert them one at a time, and point them out, so you can slide the toms on without banging them into one another. As for the correct position, there is no right or wrong way to set them up. You will need to try different ways that work for you. The Floor Tom is next. You will notice about 1/3 of the way up from the bottom that the floor tom has 3 chrome mounts. These are the leg mounts, and you will find 3 steel legs in the hardware box. They are approximately 18" - 24" in length and have an odd bend at one end, with a rubber foot. Insert these into the assemblies, and adjust to a comfortable height. The snare drum stand is the stand with the shortest legs, and it will have a set of 3 "arms" which when folded down securely hold the snare drum. It will have a large adjustable nut under the basket, which you will use to tighten the 3 arms to hold the bottom of the snare. Another knob will adjust the height of the snare. Adjust it to a comfortable position. the 3rd adjustment is the angle adjustment. It adjusts the angle of the snare drum. Again, adjust it for comfort. The bass drum pedal attaches directly to the bass drum hoop on the back side. Attach it and lock it down securely with the adjustment knob. The hi-hat stand may be in 3 pieces.. a smaller solid shaft threaded at one end, a tubular piece with the cymbal cup and the tripod stand with the pedal. The smaller shaft threads into the nut on the stand assembly, then the tubular piece slides over the shaft, and into the stand assembly. A felt washer goes into the cymbal cup, and the cymbal clutch tightens with a wing nut to the shaft. This leaves the 2 cymbal stands, which both use the same size tripod base. The straight stand will be in 2 or 3 telescopic sections, and the boom stand will have an addition piece with a hinge in the center. This allows you to place your cymbal closer to the drums.

Remember that the important thing to remember is to HAVE FUN! There is no right or wrong way to set your kit up. Try different things, and HAVE FUN! Drum Tuning Now that your kit is assembled, it's time to make it sound like a drum kit instead of...well, instead of how it sounds. While there are many techniques to achieve different types of sound and tone, virtually all of the pro's agree that you must have even head tension to eliminate unwanted ring and overtones. In other words, the tension should be the same at each tuning lug. Sound easy? Well, due to modern manufacturing techniques and better heads, it is easier than it was a few years ago. However, it still requires some practice to develop your touch and ear. Let us begin... Kick Drum: In the previous tech tip, we mentioned putting a pillow into the bass drum as a way to help with the overtones and tuning of the drum. While its possible to achieve a good punch without it, most folks (at least other band members and recording engineers) prefer to have a solid "thud" sound with a slight over ring. Whether you choose to use a pillow or not, the tuning procedure is still the same. Start by tightening the lugs until they are all finger tight. You will notice wrinkles in the head around the edges. Choose any tuning lug and tighten it 1/2 turn. Then, go directly across the head and do the same with that lug. Continue in this fashion around the drum until the wrinkles are gone and you hear a tone when you tap on the head. Once you begin fine-tuning, you will want to turn the lug no more than 1/4 turn. When tuned properly, you should hear the same pitch when you tap on the head in front of each lug. (Approximately 1" in from the rim.) Different shells sound different depending on how high or low they are tuned, so experiment with the tuning. Snare Drum: Because there are so many different types of materials used to construct snare drums, including wood, steel, copper and brass, the snare can be tuned to an amazing number of tones and textures. Again, experiment with different tunings to find the tone that works for you. I prefer a very tight, fat snare sound. To achieve this I start with the bottom snare head. Using the same technique as the bass drum, make sure the tension is even as you go around the head. I like to have the bottom head as tight as possible, which gives the snare a tight snap when I hit it. Use your own judgment. The top head I tend to keep quite a bit looser, in order to "fatten" the snare sound. If you still have too much over ring, a small piece of duct tape will help to alleviate this. Place it approximately 1" from the rim of the snare, directly across from you (this will keep you from hitting that spot with your sticks). Toms: Even tension on the top and bottom heads is critical for good tom tone. You may want to take each drum off the mount to tune the bottom head (using the same technique as above). Find a pitch that sounds good to your ear, and try to tune the drum to that pitch. Again, there is no right or wrong tuning for your kit, as long as it sounds good to you. It will take a while to tune your kit, so don't get discouraged. The best advice I can give you is to use small increments when you begin to fine-tune the drums. 1/4

turns are usually more than enough. One last tip. Placing the drum flat on a carpeted surface can also help when you are just learning to tune the drum. This dampens the other head, letting you hear just the head you are tuning. Cleaning your Cymbals To clean or not to clean, this is the question for many drummers when it comes to their cymbals. Some players believe that a certain amount of grime and grit and smoky residue adds to the character of the cymbal. No doubt that a certain barroom neglect may give your cymbals a certain roadhouse ambience. But for those who are interested in extending the life of their cymbals and keeping them shining like shining disks of pure sonic gold under the stage lights, heres some helpful tips. Many new cymbals are sprayed with a protective coating to keep them from tarnishing in the store, so your cymbals may need less cleaning during the first 6 months, depending on use. During this time, a solution of warm water and liquid dishwasher soap will clean fingerprints, dirt and grime. As your cymbals age, we recommend a professional cleaning cream to remove stick marks and tarnish. Put a small amount onto the surface with a soft cloth and rub in the direction of the tonal grooves, until the metal appears through the film. After the polish has dried to a haze, buff gently with a clean, soft cloth. Clean only a small section of the cymbal at a time. Always avoid using any abrasives, such as steel wool, wire brushes, scouring pads or metal cleaners that contain abrasives. These products will scratch the surface of your cymbal. Tips for Multi-Track Recording There are many things to consider when you are in the market for a recorder. First, what sound quality do you need? Are you making recordings for friends or to submit to the music industry? Another thing to consider is the number of tracks you need and the number of simultaneous recording tracks available. If you are only recording one person and don't intend to submit your tape, you don't need anything fancy...perhaps just a small multi-track tape machine for building songs track by track will do. These little tape machines generally use cassettes, which also makes them easy and affordable. But it's good to have certain features, such as a pitch control for changing the speed of the tape, and a high speed mode that provides more tape for the sounds being put there and hence better quality recording. With this type of recorder, there are tricks that the digital machines are just now becoming able to do, like being able to have a song recorded with an instrument track in reverse. This is easily achieved by ejecting the cassette and reinstalling it upside down, then recording the track while all the other instruments are playing in reverse, then just flip the tape and listen back. Besides the great little tricks you can do with tape machines, some say they are preferable to digital recorders simply because they have tape, which lets you get a hotter signal and greater frequency response than you get with digital machines. When selecting a cassette tape for your recorder, you want the best sound quality you can possibly achieve, so, a cassette not over 45 minutes, and normal to high bias is going to work the best. One generally thinks longer is better, but a shorter cassette will have an advantage often overlooked -- the tape is shorter, but it is also thicker, and has more available material to more securely hold the magnetic fields

created by the tape heads. Thicker tape, moving across the heads faster, is the ideal situation. Have you ever noticed that sound quality that is lost when listening back to bounced or "ping-ponged" tracks? Every time you re-record a track, since you're recording your recording, you lose a little. Here's a simple way ping-pong your analog tracks and keep the quality up. All you need is a digital VCR (most are digital after the mid 90's). The tracks you decide you'd like to bounce to another track can be mixed and sent to the inputs on the VCR. It will digitally record them to the VCR. Then just send them back into the tape recorder onto a single track. They may not be quite as good as your original tracks were, but they will be better than if bounced from one tape machine to another. One of the most important things to know about recording to tape is that you want to saturate the tape to give the recorded tracks their best possible quality. That's why tape machines generally have meters with a red area at the peak end. When recording, you want the needle as near or just into the red zone as possible, without pinning at the top. In other words, you want to be as close to distortion level as possible, without actually getting distortion. If you run it too safely, keeping it below the red zone completely, you'll avoid distortion, but not have as rich a recording as you could have. The trick is to get familiar with your machines, so you know how high the needles can run without getting distortion. Tips on Digital Recording, And Reasons for Liking It You've recorded your rhythm guitar and bass tracks. You want to add a steel drum track but discover that the steel drum is grossly out of tune (as they often are). With most digital recorders, this is no problem. The recorder's speed can be changed to match the steel drum or keyboard or whatever. After the instrument is recorded, the machine can be returned to its original track speed with everything in tune. One of the things you learn to love about a digital recorder is not having to wait while tapes rewind or fast forward, watching the counter so you don't run past the point you want to stop at. Digital machines relocate automatically, instantly. The machine just draws its information from a different place, rather than physically having to go there. Since most machines allow for different sample rates, they can be adapted for optimum sound quality but less recording time, or lower resolution but extended recording time. This makes a digital recorder flexible, great for recording single songs at max quality, and also capable of recording long concerts without interruption. Lower the sample rate and record on two tracks continuously for hours. On lower-end tape machines, punching in can be a problem in that it can be heard on the tape. Low end digital machines perform punch ins in a millisecond so every punch stays silent on the recording. Tabletop digital studios may seem to have only simple controls compared to analog mixing boards. Each button, however, can call up several menus that give you control choices that can equate to those provided by a sophisticated mixing board with jillions of knobs. Most digital recorders can be used to step time for sequencing and be made to run the scenes in light shows, or switch the effects on most digital mixers. Many digital recorders use zip disks or some similar removable media rather than internal hard disks. This makes them especially easy for collaborating. If you and

your buddy in Wisconsin have the same machine, you can mail zip disks back and forth. You don't have be around each other at all to make records together. Storing your digital recordings is tidier than storing tape. Tapes don't like temperature extremes, or high humidity, and they get brittle after a few years. Digital recordings can be put stored on Zip Disks, Jaz disks, or CD ROMs that store better longer. Speaker Impedance The simplified explanation: Impedance is the tendency of a circuit to resist the flow of AC electricity and is measured in ohms. As the impedance goes up, it's harder for the electricity to get through. A good analogy would be to water flowing through a pipe. As the pipe diameter gets bigger, the water flows through it more easily. The bigger the pipe, the lower the resistance or impedance. An amplifier's output transformer is designed to work with a particular impedance level (or more than one if it has switchable settings). Matching the correct speaker impedance to the amp transformer is important. If mismatched, the transformer and other amp components can be damaged. Most speakers used today are either 4, 8, or 16 ohms. The more technical explanation: Impedance is the combination of reactance (which changes with frequency), and resistance (which does not change with frequency). Thus the speaker's impedance actually changes depending on the frequency of the signal it is receiving. However, speakers are generally rated at a standard frequency level, resulting in the uniform 4, 8, and 16 ohm ratings. It's when you wire several speakers together that things get freaky. Adding two speakers together, for example, can result in different impedances. It all depends on how they are hooked together, in series or in parallel. Two 8 ohm speakers wired together can result in 16 ohms (in series) or 4 ohms (in parallel). Here's why. In series, all the current is flowing through them one after another; thus, they represent a larger impedance than a single speaker, the sum of their individual impedances. If you wire them in parallel, the current has two different paths to choose from and will split up evenly between them (assuming the speakers have the same impedance). Thus, the total impedance will be less than the impedance of either single speaker. The formula for finding the impedance for speakers wired in parallel is the product of the two speaker ratings (8 x 8 = 64), divided by the sum (8 + 8 = 16). So two 8 ohm speakers would result in 4 ohms (64 divided by 16 = 4). Wiring parallel is the only way to add speakers together without adding reactive loads. Four FAQs for Beginning Bass Players 1. How are basses tuned? Four-string electric and upright basses are tuned in perfect fourths, E A D G from low to high. Five-string basses commonly add a low B, but some add a high C instead of the low B. Six-string basses usually have both the high C and the low B. Seven-string basses add an F# to the six-string layout. Eight-string basses are like 12-string guitars. There's an extra string added to each of the four standard strings, with the second set tuned an octave higher. 12-string-basses add two "octave" strings to the pair, making 4 sets of three strings. 2. What is the difference between J-pickups, P-pickups & Soapbars?

The P in P-pickups stands for Precision Bass. They are made of two single coil pickups that are offset so they each pick up vibrations from two different strings. The signal is combined before it reaches the volume and tone controls. Each single-coil is wound in opposite directions to reduce hum. Basses usually have one P-pickup. The J in J-pickups stands for Jazz Bass. They are made in one piece that picks up vibrations from all four strings. J-pickups are single coils, and J-bases usually have two of them: one near the neck and one by the bridge. Soapbar pickups owe their name to their shape. These one-piece pickups are about twice as wide as J-pickups, and can be wired as either single-coils or humbuckers. 3. What's the difference between bass strings? There are two main flavors of bass strings: roundwound and flatwound. All wound strings are made by wrapping layers of wire around a core wire. Roundwound strings use a round wire as the wrap, flatwound strings use a flat ribbon wire. Roundwound strings deliver brighter sounds, but can emphasize squeaks. Flatwound strings have a duller sound, with less extra noise. Flatwound strings tend to keep a more consistent tone longer. Here's an extra tip: You can rejuvenate your roundwound strings by boiling them in vinegar or mild detergent solutions. It really works. 4. What is Biamping? Biamping splits the signal from the bass preamp using a crossover. The highs are split from the lows and each is sent to a different power stage in the amp, and to separate speaker cabs. Low frequencies require more power to deliver the same volume, so this is ideal for situations where you have one cab with smaller drivers (4 x 10) for the highs and another cab with meatier speakers (4 x 15) for the lows. A MIDI Note Many folks get confused about the purpose of a midi connection with regards to what is transmitted. MIDI is a control language of 1's and 0's. It is used to send information from one device to another (like from a keyboard to a sound module). One of the most misunderstood ideas with MIDI is the idea that audio is transmitted from the MIDI ports. MIDI ports aren't set up to be used as sound outputs (you can't send your keyboard's audio to the computer through the MIDI ports). What does come out of a MIDI port is a stream of data consisting of 1's and 0's. What MIDI does is send command information from one device to others. Think of a television remote control. Does any of the programming you see and hear originate from your handheld remote unit? No. All the remote does is tell the television what to show and how loud the volume should be (and perhaps some more advanced features like picture in picture....would that be called a multitimbral television???) Your MIDI controller simply sends what note should sound, perhaps how loudly, what patch or parameter to use, etc.. MIDI can be confusing, and there are new protocols being developed all the time, but beginning with a good understanding of what it does not do can help make the learning curve an easier thing to overcome. What's the difference between a tube amp and a solid-state amp? The simple answer is that a tube amp uses one or more vacuum tubes to amplify the signal, while a solid-state amp uses solid-state electronics (diodes, transistors, etc.)

to amplify the signal. On paper and in theory these two implementations should yield identical result, but in actuality the difference is usually noticeable. But the simple answer fails to answer to the complexity of the issue. Many amps are not simply tube or solid-state, but mixes of both kinds, called "hybrids." This usually means that they have a tube preamp stage, employing vacuum tubes in the tone shaping circuitry, but use solid-state circuitry for the power section. The hybrids are closer to full tube amps in response and tonal warmth, but purists will still find a difference between the two. Tube amps are generally more expensive in initial cost and to operate (because you need to replace the tubes occasionally), and solid-state amps are generally less delicate and more reliable. Many players, however, feel that tube amps yield a warmer, more musical tone and better distortion. Yet another wrinkle is tube emulation circuitry. Many amps and preamps have sophisticated circuits designed to act like tubes, and as in all things, some are better than others. The newest develop in amps are the modeling amps, which not only emulate the tone and response of tubes, but of specific tube amps. These are in general pretty exciting amps, but again, some are better than others at getting specific models, and in maintaining the sounds through a range of volume levels. Another point to make about tube amps is that bigger is not always better. You get the distinctive tube sound most when the amp is cranked up enough that the tubes are saturated or nearly saturated. For this reason, it is often better to choose a lower wattage amp over a higher wattage amp, depending on how and where you play. By the time you crank up your 60 watt amp enough to saturate the tubes to get just the right level of distortion, you could be blowing your audience out the back door. It might have been better to choose a 20W amp that lets you get your saturated tone without the ear-killing decibels. How to Make Orchestral Samples Sound More Realistic? Samples won't ever sound exactly like real orchestral instruments. But they can sound fairly close. Here are a few helpful principles to remember. Be sure to play the samples within the range of the actual acoustic instrument. Use phrasing and dynamics appropriate to each instrument. MIDI volume can add expression to phrasing. Don't sustain wind instrument samples beyond a wind player's breath capacity. Ranges and idiomatic instrumental usage can be found in orchestration books. Avoid playing anything on a sampled instrument that can't be played on the real instrument. Vibrato can be problematic. When a sample with natural vibrato is played more than a half-step above or below the note at which it was sampled the vibrato speed will be inconsistent, especially with wind instruments. In such instances, use samples without vibrato, which can be added via LFO or pitch-bend wheel. In an orchestra, instruments occupy a given place on a stage or in a room. Use mono samples, and pan instrument sections to a consistent location. Reverb can help simulate front-to-back placement, as wee as add hall ambience. Examples of orchestral seatings can be found in some orchestration books. Samples can be recorded with various mic placements and effects processing. Maintain consistency as much as possible; effects processing can help. Orchestration books are invaluable. Books on MIDI orchestration are even more to the point.

Which recording format is best for a home studio?* Each format has its advantages and disadvantages. Decide which one most closely fits your needs, and then check out the features of various makes and models. Digital multi-track recorders get your music onto tape quickly and easily, plus they're portable. Archiving your work is inexpensive. However, they have no cut and paste editing or built-in audio processing. Punch-in recording writes over the original material. Making backups requires multiple recorders. Mixdown may require an external mixer. Stand-alone hard-disk recorders are capable of detailed editing, and they offer immediate access to any location. Usually, a mixer is built-in. On some units, automated mixing, onboard effects, and/or timecode capability may be included. And they're portable. But some use data compression, and the editing screen may be small. Archiving media is more expensive than digital tape. On some machines, punch-ins and bouncing are destructive; on others, they can be undone. Computer-based hard-disk recorders have the advantage of a large screen for editing. There are many high-quality software plug-ins for processing. Punch-ins and track bounces are non-destructive. Automated mixing is built-in. Most recording software also includes MIDI sequencing. However, a system can be expensive, including a powerful computer, an audio card, software, and an archiving media. And it's not portable. Mini-Disc multi-track recorders are very affordable, portable, and include a built-in mixer. They offer some editing capabilities, but not as extensive as those on harddisk or computer-based systems. Unfortunately, they use data compression, which increases with each track bounce, diminishing the sound quality. Backups can't be made. Analog tape recording is less of an option these days. The sound of a high-end analog tape recorder can't be beat, but the cost is high. Cassette recorders are OK for capturing an idea quickly, but their sound quality is far below that of a digital system. MIDI sequencing offers detailed editing, but it's restricted to electronic sound sources, so vocals or acoustic instruments can't be recorded. However, most MIDI sequencing programs include some audio recording capability, so the two formats can be easily integrated. Many home studio owners use combinations of the above, such as a digital multitrack recorder coupled with audio editing software. Don't forget to budget in a mixdown deck, whichever is appropriate: CD recorder, 2-track DAT recorder, or 2track cassette recorder. Easy Steps to Making Music On Your Home Computer Any computer purchased in the last few years has the basic hardware for making music. Computers with a hard drive smaller than 2Gb and a CPU slower then 100mhz is going to limit you to a few tracks at best. The bigger and faster your home computer, the more powerful your recording capabilities. Besides your computer, all you need a microphone and software, and you're ready to record. Multi-track recording software is relatively easy to use. You don't need a science degree to figure them out. Many programs are designed specifically for regular musicians, and most offer a minimum of 8-track recording. Some programs come equipped with full MIDI capabilities, virtual drum features, and multi-effects.

Actually recording is as easy as loading your software into your computer, plugging your mic into the sound card, and playing. Soloists can record one rhythm track, then record another lead track while your previous track plays back into your headphones, then add vocals on a third track.You can keep adding as many tracks as your computer or software can handle. Most software lets you add effects on each track. A word to the wise: even the fastest computers start bogging down with too many simultaneous effects in real time. Usually these 'bogs' will sound fine when you mixdown, when the processor can handle extra effects because it isn't fixed to real time. Computer noise can be a pain when recording. The easiest thing to do is to put your computer under your desk. Better yet, buy extra long cords for all you peripherals and stick your computer in the next room. Of course you'll want to pick up a few cool extras. Perhaps a better sound card, superior mic, a mic mixer and preamp, and maybe a MIDI keyboard. And then you'll need to burn your own CDs.... What are speaker crossovers? Single speakers don't have a flat frequency response over the entire range of audible frequencies. That's why most cabs contain more than one speaker. The biggest speaker is the woofer. It's for the low frequencies. The smallest, the tweeter, is designed to project high frequencies. The third speaker is for mid-range. Speaker cabinets have a crossover built in to prevent these speakers from overloading. A speaker crossover is a filter system that takes the incoming audio signal and splits it into chunks that each speaker can handle. If you have a woofer and tweeter, then the crossover has a lowpass and highpass filter. A third bandpass filter handles the mid-range frequencies. Which guitar effects are better: Single-effect stomp boxes or multi-effects pedals? Multi-effects devices offer several effects in one package and blend usually blend effects into presets or patches. There are a lot of cool multi-effects pedals out there that give you a bigger bang for your buck...if you're looking at a dollar-per-effect ratio. After all, some sacrifices have to be made to squeeze all those multi-effects into a small box and keep the price low. Individual, dedicated effect pedals often deliver superior effects with a wider rage of adjustabilitybut they cost more on a per/effect basis. In other words, you can typically get more sonic quality and more variations on a single- effect pedal. Some little multi-effects pedals deliver some very nifty, high-quality sounds and some editing ability. It really comes down to personal taste, and which types of effects sound best with your music. Here's the bottom line: If your music requires multi-effects, then you need a whopping multi-effects pedal. But if you're only going to use a few effects, you may be better served by dedicated stomp boxes. In the end, the music will tell you exactly what it needs. Expanders and Noise Gates

Expanders are dynamic processors that increases the dynamic range of a signal. They make loud sounds louder and soft sounds softer. They're like an amplifier with a variable gain control, and the gain is controlled by the level of the input signal. Expanders are used by musicians to produce more extremes in recordings that have a limited dynamic range. This gives the music more intense dynamics. Noise gates are usually used to eliminate unwanted noise and hiss which would otherwise be heard when an instrument is not being played. The noise gate's threshold needs to be at the precise point so unwanted noise falls below it, and he instrument's complete notes can be heard. Expanders and noise gates should be near the end of the effects chain, so noise created by other effects can be "gated" when you're not playing. I place my delay and reverb effects after the noise gate so their sounds trail off naturally. About Equalizers Equalizers boost or cut specific frequencies in a signal. The most common equalizers are tone controls. They tailor your sound to suit your music. Bass and treble knobs control a lowpass shelving filter and a highpass shelving filter. Lowpass and highpass filters remove a portion of the sound spectrum. But shelving filters just pump up or reduce one portion while leaving the rest alone.There are also 'mid' controls found on 3-band equalizers. This 'mid' is sometimes called a peaking or bandpass filter. Graphic equalizers provide more flexibility and control than tone controls, and they're easy to use. A graphic equalizer is a set of filters that allow you to control the amount of boost or cut in each frequency band. Controlled with sliders, the frequency response of the equalizer resembles the positions of the sliders, that's why it's called a 'graphic' equalizer. A graphic equalizer uses a set of bandpass filters that are designed to completely isolate certain frequency bands. Each filter in the graphic equalizer has the same input. Their job is to only allow a small band of frequencies through. Graphic EQ's are great for sound reinforcement and 'tuning' rooms. With a graphic equalizer that covers most of the audio spectrum, you can adjust your EQ so that you have a consistent sound at every venue. For instruments, stomp-box equalizers are great for delivering a both a volume boost and changing tone for solo excursions. Parametric equalizers give you the most flexibility, but are a bit more difficult to use. Unlike graphic EQ, that only lets you set the amount of boost and cut, parametric EQ allows you to also set the center frequency and the bandwidth. With practice, you can apply some boost to make a guitar cut through the mix, or to get a big, full sound. Parametric EQs can eliminate feedback by using a lot of cut (also called a notch filter) positioned right at the frequency that is feeding back. You might be able to control the feedback with a graphic EQ, but if its bands are wide, you'll be cutting more of the sounds than you wanted. Parametric lets you fine-tune the cut, so you don't lose the good stuff. Many amplifiers have 'presence' knob that boosts the mid to high frequencies. This control is supposed to make your instrument sound like it is actually in the room on recordings. It also helps an instrument slice through a muddy mix.

Compressors & Limiters Compressors reduce a signal's dynamic range. It does this by reducing the gain when the signal level is high, making louder passages softer, and the dynamic range smaller. It is used in audio recording, production work, noise reduction, and live performance applications. When signal levels get too high when recording, there will be distortion. Compressors and limiters provide protection against sudden transient sounds that could distort your sound or damage your equipment. It is also used for cutting tracks and adjusting the mix. It can smooth volume changes, adjust the dynamic range and balance of a track. Compression can also increase an instrument's sustain. It amplifies the incoming signal to maintain a constant level, so after twanging a string, a little compression will preserve the string's sound. While adding sustain to your arsenal, compression also reduces your dynamics, making it difficult to accent notes and phrases. Be cool about compressing for the sake of sustain. If you need to have a signal's level controlled by a different signal, it is called 'ducking' (it 'ducks' a signal out of the way) or cross limiting. Here's an example: While music is playing, using the microphone will cause the level of the music to drop so that it's easier to hear the singer. When mixing in the studio, a ducker can also be used to make certain instruments pop out of the mix. A 'de-esser' is a limiter that monitors only a specific frequency range. It only reduces the level of frequencies in a selected range. This allows you to reduce unwanted sounds. When using a compressor with other effects, many players put it first in the chain. First, it gives you a good signal to work with. And when the compressor is on and the output level is increased, the noise will be amplified along with the instrument's sound. Other effects can introduce more noise, so if the compressor is placed after those effects, it will end up amplifying their noises, too. What is a Chorus effect? Chorus effects can make a single instrument sound like a group of players. It adds a rich, lush, shimmering quality to your sound. Here's how it works: when 2 people play the same song together, there is naturally some delay between the sounds they produce. The pitch of the instruments can also differ a bit. This is exactly what the chorus effect does. A delay line is used to get the slight delay, and by varying that delay, the pitch is slightly detuned. The result is the rich, shining sound of two instruments playing at almost the same time. Chorus is commonly used with acoustic electric guitars to fatten up the sound and give it extra sparkle. There are a variety of cool chorus units available as dedicated stomp boxes, multi-effects units, or studio processors What is a Delay? Delay is one of the simplest effects out there and one of the most valuable. A little delay can bring life to dull mixes, widen your instrument's sound, and even allow you to solo over yourself. Delay is the also a cornerstone of other effects, such as reverb, chorus, and flanging.

Delay is created by taking an audio signal and playing it back after the delay time. The delay time can range from several milliseconds to several seconds. Most delays have a control that allows you to repeat the sound over and over, and it becomes quieter each time it plays back. Long delay times can open up some cool possibilities. Once you get over a second, you can virtually loop on the fly. Just pay a riff, then play over that riff while its repeating. You can actually solo over yourself when you don't have a rhythm player. A slapback delay has a very short delay time, usually between 30 and 100 milliseconds. Most folks consider a longer delay an echo. Multi-tap delays allow you to create more complex patterns. Taking outputs from points within the delay line is called 'tapping'. The amount of delay between the various taps can be different. You can set the multi-tap delay to follow the rhythm of a song, or create amazing textures. Ping-Pong delay bounces between the left and right channels of a stereo signal. It uses two distinct delay lines, each driven by an input. This produces two output signals, that create the classic 'bouncing' sound when panned hard left and right. What are Phase Shifters & Flangers? Phase shifters (or phasers) and flangers get their sound by creating one or more notches in the signal's frequency. The notches are created by filtering the signal, and mixing the filter output with the input signal. The filters can control the location, number of notches, and width of the notches. Most phase shifters start with a simple filter, then add more filter stages to create more notches. A stereo phaser uses two filters with notches at different frequencies. You can also create more complex sounds by mixing the outputs of the two filters. This can give you virtually endless sonic possibilities. From subtle rotating-speaker effects, to swirling, edge-city sounds from classic 60's guitar solos, phasers can be a very useful addition to any player's arsenal. Flangers produce the unmistakable jet-engine "whooshing" sound. Basically a type of phasing, a flanger creates a set of equally spaced notches in the audio spectrum. Phasing also uses notches, but multiple filters and user controls create random spacing. What do I need to record a CD with my computer?? We can list only the most basic components here. The following items can get you started. First, of course, you need a computer and a CD Burning program. There are a number of good programs for both Macs and PCs. There are two types of computer-based CD-recording (CD-R) units, SCSI and IDE. A SCSI CD-R is preferable because it's significantly faster, and it's less likely to fail due to inability to transfer information with sufficient speed. IDE devices are usually, but not always, fast enough, so get a SCSI device if you can. If you don't already have a SCSI interface on your computer, you'll also need a SCSI adapter card. Preferably, get an adapter that converts a PCI slot to SCSI; adapters that convert ISA slots are much slower. You'll need a hard drive with at least a gigabyte of usable space. CDs hold about

650Mb of data, but more is needed to handle the buffers in the recording software. Actually, two gigs of usable space are better, because you may want room for some audio processing software plug-ins. Ideally, use a separate hard drive for your CD recording. An audio interface is needed to get the audio into and out of the computer. Some audio interfaces have analog inputs/outputs (I/Os), some have digital, and others have both. Digital I/Os transfer the highest quality sound, by far. You may want both analog and digital I/Os - the digital I/O to record DAT tapes and CDs, the analog I/O for LPs and live recording. Also, PCI cards are superior to ISA cards, because they are faster and susceptible to fewer hardware conflicts. Many audio interfaces also include CD Recording software. CDs sample at 44.1kHz. If your audio source was recorded digitally at 32 or 48kHz, you'll need to convert the sample rate to 44.1. Some soundcards can resample in realtime, a fast and efficient solution. Some recording software can convert the sample rate by resampling the data that was recorded onto the hard drive. This can be time-consuming, depending on the speed of the computer. Outboard resamplers are quick and effective, but more expensive. Obviously, if your source was recorded at 44.1kHz, you don't have to convert the sample rate. One more item is needed - a blank recordable WORM CD. WORM stands for Write Once, Read Multiple. It works just like a standard CD, and you can play it in any CD player. We haven't even scratched the surface of CD recording here, but we hope you now have an idea of what you'll need. How to Get Rid of Single Coil hum without Getting Rid of Single-Coil Tone Turn up your Strat (or any guitar equipped with standard single-coil pickups) and you get a certain amount of hum and buzz, especially if playing under flourescent lights or near anything that creates a strong electromagnetic field. If you find this sound hideously irritating, as many do, you might consider a guitar with humbucking pickups. That's the extreme alternative...sort of like throwing the baby out with the bath water, because you get rid of the hum problem, but you also get rid of that twangy, out-of-phase tone that single-coils get. The classic Fender tone, as it could be described. One way to beat the problem (still fairly radical) is to go active. With an active preamp system in your guitar and a set of such pickups as Duncan Live Wiires, you cure the problem. But there is yet another solution, short of trading in your guitar or routing it out to make room for humbuckers or active electronics. There is a group of pickups designed to be hum-cancelling or "bucking," but which retain the essential single-coil sound. Seymour Duncan makes several. The "Classic Stack" has the dual coils of a humbucker, but they are stacked so that the pickup has the dimensions of a single coil. It also retains the sound of a single coil, but without the hum. Their Vintage Rail pickup is another that accomplishes the same mission, single-coil sound without the hum. Another pickup that is growing in popularity is the DiMarzio Virtual Vintage. Fender itself has several new designs that you can use as pop-in replacements on your Strat. These are Lace Sensors and Vintage Noiseless. Most of the Lace Sensors get a humbucker sound, but the Gold is designed for a vintage tone, a glassy, bell-like sound with crisp highs. Even closer in tone to your vintage single coils are Fenders new Vintage Noiseless pickups. In this case, Fender's noiseless

technology has very successfully minimized the noise while retaining the tone. This isn't an exaustive list, but long enough to show you that there are alternative ways to keep your single-coil equipped guitar "as is" vintagy, but with sweet silence, rather than buzz, between the notes. What compression settings are appropriate for recording electric bass? Since the electric bass has a wider dynamic range than many instruments, compression is often applied in order to maintain a more even volume level and to match the dynamics of the kick drum. When peaks are reduced, the entire bass part can be boosted in the mix without adding distortion. The settings depend upon both the music and the playing style of the bassist. It's necessary to listen to the part and adjust the compression settings to obtain the sound you want. If the compressor has an input level, adjust it to get a nice hot signal, but not loud enough to clip. The threshold level determines the maximum level - signals louder than the threshold are reduced in volume. At 0dB, only the loudest signals (peaks) are compressed, retaining most of the natural dynamics of the player. Settings between -2dB and -5dB are often used; when even more compression is desired, a threshold of as much as -10dB or even -15dB might be chosen. The ratio setting determines how much the signal is reducSince the electric bass has a wider dynamic range than many instruments, compression is often applied in order to maintain a more even volume level and to match the dynamics of the kick drum. When peaks are reduced, the entire bass part can be boosted in the mix without adding distortion.The settings depend upon both the music and the playing style of the bassist. It's necessary to listen to the part and adjust the compression settings to obtain the sound you want.If the compressor has an input level, adjust it to get a nice hot signal, but not loud enough to clip. The threshold level determines the maximum level - signals louder than the threshold are reduced in volume. At 0dB, only the loudest signals (peaks) are compressed, retaining most of the natural dynamics of the player. Settings between -2dB and -5dB are often used; when even more compression is desired, a threshold of as much as -10dB or even -15dB might be chosen. The ratio setting determines how much the signal is reduced. The higher the ratio, the more the signal is compressed. A 2:1 ratio cuts the output of any signal above the threshold in half; a 3:1 ratio reduces a signal above the threshold by 2/3. A ratio of 3:1 is a good place to begin in your search for the optimum ratio. 4:1 is also widely used, but occasionally a ratio as high as 10:1 will suit the sound. The attack setting determines how quickly the peak is reduced. Slower attack times allow the initial transient of the note to come through, for a punchier sound. If the attack is fast, all sharp peaks will be cut, and the part will be smoother. A medium attack time of 20ms to 40ms is a good starting place. The decay time determines how quickly the compression goes away. If it's set too low, it may compress a quieter note that rapidly follows an above-the-threshold note. A medium setting is good - fast enough to be ready for a quiet note, not so fast that it boosts noise that occurs between notes. Between 125ms to 250ms is usually appropriate for bass. A compressor may allow you to select between hard-knee and soft-knee. Set on hard-knee, the compressor waits until the signal crosses the threshold, then it

reduces the signal at the specified ratio for a punchy sound. With soft-knee compression, the ratio gradually increases as the signal approaches the threshold, resulting in a more natural feel and a wider dynamic range. If the output level is equal to the level of the peaks of the uncompressed signal, the overall loudness will be higher. However, cheap compressors may add noise when theoutput level is raised, so it may be preferable to boost the volume at the mixing board. Adjusting one setting affects other settings. For example, an adjustment to the threshold may require an additional adjustment to the ratio. Keep at it until you get the sound that fits. Proper Care and Feeding of Tube Amps First, you should try to make a habit of firing up your amp in Power/Standby mode for at least one minute before pounding the current completely to all tubes. This way, when the tubes get the full jolt of electricity, the plates are nice and warm. Hot current hitting cold tubes is one of the worst things that can happen to a tube amp. Using the warm-up procedure can really extend the life your tubes. Switching the amp to standby for breaks also helps extend tube life. There are very good reasons tube amp manufacturers put standby switches on their amps. Using them properly is the best thing you can do for your amp. You can tell if youre firing up your amp properly when youre quietly strumming your strings, waiting for the tubes to come on-line. If you have a fully audible signal and hear the notes clearly the instant you hit the switch, your doing the right thing. Some players recommend changing tubes almost annually. Ive owned tube amps for years and have never yet changed or had a tube go bad. Actually, moderately worn tubes sound better than new ones, and if properly cared for, just keep sounding better and better. I have to give credit to the folks at Mesa Boogie for teaching me these tube amp tips nearly 20 years ago. (Note: Mesa Boogie still offers this advice in their new owners manuals).

Phantom Power...No Big Mystery

The only person who need even think about phantom power is he who is equipping a studio and purchasing a board and mics, or the performer who wants to use a condenser mic on stage. What phantom power does is reside in the board (or in a separate supply box) and power condenser mics (the high-end, serious recording type condenser mics). It's nice to have a mixing board with phantom power capability. Otherwises you need an outboard supply box (these come in various sizes from single channel boxes up to eight or more channels), and that means an additional expense and more hassle. Is phantom power better? It's all electricity, but one could consider it a more stable source than a battery which eventually runs low on juice. Who else might benefit from phantom power? Bassists and guitarists who are using active D.I. boxes. Some of these units (such as the Sansamp) can be run on phantom power if connected to a board that provides it. Saves money on batteries, or saves you the hassle of plugging in a power supply, and phantom power won't disappear into the night as battery power can.

You might also like

- Gain Staging With A VU Meter Cheat SheetDocument4 pagesGain Staging With A VU Meter Cheat Sheetchesososa28010% (1)

- Yamaha mg06x mg06 Mixing Console PDFDocument46 pagesYamaha mg06x mg06 Mixing Console PDFAlfred Manfred50% (2)

- CS3 Mods PDFDocument6 pagesCS3 Mods PDFAnonymous LgJH9UE2jNo ratings yet

- Dummy Coils For PickupsDocument2 pagesDummy Coils For PickupsRoland CziliNo ratings yet

- Tele 4 Way DiagramDocument1 pageTele 4 Way DiagramNat DiaNo ratings yet

- Uses DBX 146221Document8 pagesUses DBX 146221shirtquittersNo ratings yet

- Diagramma ZED12FX 16FX 22FXUGDocument1 pageDiagramma ZED12FX 16FX 22FXUGgiovanniricciardiNo ratings yet

- 421m AGC-Leveler With Mic/Line Input: He Symetrix 421M Is A Sophisticated Audio Gain Controller, But What ItDocument2 pages421m AGC-Leveler With Mic/Line Input: He Symetrix 421M Is A Sophisticated Audio Gain Controller, But What Itmr.sanyNo ratings yet

- Buying, Caring For, and Maintaining Your Acoustic Guitar - The Ultimate Beginner's GuideFrom EverandBuying, Caring For, and Maintaining Your Acoustic Guitar - The Ultimate Beginner's GuideNo ratings yet

- The Chromacaster User's Manual & Guide: The Neck/Reverse ModelDocument8 pagesThe Chromacaster User's Manual & Guide: The Neck/Reverse ModelChris EfstathiouNo ratings yet

- Make Your Own FinalDocument29 pagesMake Your Own Finalapi-240491478100% (1)

- Mustang With 2 Single Coil Sized Humbuckers: Red & White Wires Get Soldered Together and Taped OffDocument1 pageMustang With 2 Single Coil Sized Humbuckers: Red & White Wires Get Soldered Together and Taped OffNebojša JoksimovićNo ratings yet

- Pickup Wiring Guide: GFS 5 Wire Humbuckers, MM Pro NDocument2 pagesPickup Wiring Guide: GFS 5 Wire Humbuckers, MM Pro NSérgio Gomes JordãoNo ratings yet

- Treble Bleed Mods: Normal Volume Pot Wiring Wiring With Treble Bleed CapDocument3 pagesTreble Bleed Mods: Normal Volume Pot Wiring Wiring With Treble Bleed Capokr15No ratings yet

- Adjusting Pickup HeightDocument8 pagesAdjusting Pickup HeightmarcosNo ratings yet

- Humbucker Wires Color Code Diagram PDFDocument1 pageHumbucker Wires Color Code Diagram PDFfivehours5No ratings yet

- 2015 Les Paul Deluxe SpecsDocument6 pages2015 Les Paul Deluxe SpecsuiupartNo ratings yet

- Tubeprimerandselection320 1Document89 pagesTubeprimerandselection320 1Leonardo RodriguesNo ratings yet

- Tele Standard PDFDocument1 pageTele Standard PDFNebojša JoksimovićNo ratings yet

- Tool Luthier and SetupDocument8 pagesTool Luthier and SetupSamuel David CastilloTorresNo ratings yet

- 2015 Squier Illustrated Price List PDFDocument24 pages2015 Squier Illustrated Price List PDFHernan LugoNo ratings yet

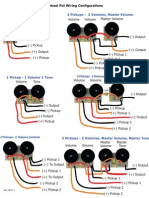

- 1 Pickup Volume Control 2 Pickups - 2 Volumes, Master VolumeDocument1 page1 Pickup Volume Control 2 Pickups - 2 Volumes, Master VolumeGuitar RoomNo ratings yet

- 2017 CatalogDocument13 pages2017 CatalogSutrisno BWINo ratings yet

- Seymour Duncan - Pickup Booster V2Document1 pageSeymour Duncan - Pickup Booster V2David BrownNo ratings yet

- Digital Booklet - Outlaw Gentlemen &Document19 pagesDigital Booklet - Outlaw Gentlemen &Sebastian Monroy PérezNo ratings yet

- Rothstein Guitars - Serious Tone For The Serious PlayerDocument8 pagesRothstein Guitars - Serious Tone For The Serious PlayerPetr Petrov100% (1)

- U.S. Patent 5,932,827, Entitled "Sustainer For Musical Instrument", To Osborne, Aug. 3, 1999.Document58 pagesU.S. Patent 5,932,827, Entitled "Sustainer For Musical Instrument", To Osborne, Aug. 3, 1999.Anonymous a7S1qyXNo ratings yet

- 2012 CatalogDocument40 pages2012 Catalog55skidooNo ratings yet

- MODboards LoDocument6 pagesMODboards Lomike2russell-2No ratings yet

- 3 Way Switch Translation: 3-Way Blade-Style Switch 3-Way Gibson-Style ToggleDocument1 page3 Way Switch Translation: 3-Way Blade-Style Switch 3-Way Gibson-Style ToggleFranco MathsonNo ratings yet

- U.S. Patent 8,853,517, Entitled Musical Instrument Pickup, To George Dixon, Dated Oct. 7, 2014 PDFDocument38 pagesU.S. Patent 8,853,517, Entitled Musical Instrument Pickup, To George Dixon, Dated Oct. 7, 2014 PDFAnonymous a7S1qyXNo ratings yet

- Seymour Duncan How To Pick A Pickup The Factors That Affect Your Guitar ToneDocument4 pagesSeymour Duncan How To Pick A Pickup The Factors That Affect Your Guitar ToneJulio C. Ortiz Mesias100% (1)

- 31.0 Thermal Considerations: 31.1 Computer Finite Element AnalysisDocument4 pages31.0 Thermal Considerations: 31.1 Computer Finite Element Analysisbuggy buggerNo ratings yet

- Audio Recording: SearchDocument10 pagesAudio Recording: Searchnavarro_pauljohn780No ratings yet

- The Big Muff π PageDocument16 pagesThe Big Muff π PageRobbyana 'oby' SudrajatNo ratings yet

- Zulfadhli Mohamad, Simon Dixon, Christopher Harte,: Digitally Moving An Electric Guitar PickupDocument8 pagesZulfadhli Mohamad, Simon Dixon, Christopher Harte,: Digitally Moving An Electric Guitar PickupwhitefloydbandNo ratings yet

- Reference Manual: ENGLISH (1 - 55)Document60 pagesReference Manual: ENGLISH (1 - 55)Anonymous stoudVe3rNNo ratings yet

- Marshall Plexi 1987x SchemeaticDocument4 pagesMarshall Plexi 1987x SchemeaticIñaki ToneMonsterNo ratings yet

- 2008 Squier Frontline CatalogDocument17 pages2008 Squier Frontline CatalogJason RobertsNo ratings yet

- EE3444LabManualV1 1Document111 pagesEE3444LabManualV1 1aspen76rtNo ratings yet

- Ultra Strat ModDocument6 pagesUltra Strat ModShane CampbellNo ratings yet

- A Mod For The Fender Blues JR.: First ImpressionsDocument2 pagesA Mod For The Fender Blues JR.: First ImpressionsErika PetersonNo ratings yet

- Fender Illustrated Product Guide 2017Document251 pagesFender Illustrated Product Guide 2017Sergei Black100% (1)

- 1 Humbucker - 1 Volume 3 Way Mini-Toggle: Series/Split/Parallel SwitchDocument1 page1 Humbucker - 1 Volume 3 Way Mini-Toggle: Series/Split/Parallel SwitchGülbahar100% (1)

- Telecaster-Singlebucking" How To Make A Strat-Style-Pickup (Humbucker) Fit in A Telecaster-Bridge"Document9 pagesTelecaster-Singlebucking" How To Make A Strat-Style-Pickup (Humbucker) Fit in A Telecaster-Bridge"George GryphoneNo ratings yet

- 15 - Seymour Duncan Hot Rails STHR 1n PDFDocument2 pages15 - Seymour Duncan Hot Rails STHR 1n PDFKris Van HalenNo ratings yet

- Electric Guitar PickupsDocument3 pagesElectric Guitar PickupsRégis Alves100% (1)

- The Ultimate Guide To Strat ToneDocument16 pagesThe Ultimate Guide To Strat Tonesomomi2239No ratings yet

- Boss DS-1 UsDocument6 pagesBoss DS-1 UsΑλκμήνη ΤσιώληNo ratings yet

- Telecaster Showmaster Stratocaster Esquire Jaguar NocasterDocument10 pagesTelecaster Showmaster Stratocaster Esquire Jaguar Nocasterdino_ibidNo ratings yet

- Pickup GuideDocument2 pagesPickup GuidenoeryatiNo ratings yet

- Replacing Damaged JacksDocument8 pagesReplacing Damaged JacksnioprenNo ratings yet

- Watts Tube Audio - Capacitor Code ChartDocument3 pagesWatts Tube Audio - Capacitor Code ChartMiguel GoffredoNo ratings yet

- Modificando Fender Blues JuniorDocument17 pagesModificando Fender Blues JuniorWandersonHortaNo ratings yet

- Tektronix CookbookDocument23 pagesTektronix CookbookbiotekyNo ratings yet

- Build Your Own DI Box!: Hand-Wired Audio ProductsDocument4 pagesBuild Your Own DI Box!: Hand-Wired Audio Productsjuan0069No ratings yet

- 2005 ESP CatalogDocument35 pages2005 ESP CatalogAries RidwanNo ratings yet

- 2 Singles 1 Volume - 1 Tone 4 Way Blade: Location For Ground (Earth) ConnectionsDocument1 page2 Singles 1 Volume - 1 Tone 4 Way Blade: Location For Ground (Earth) ConnectionsNebojša JoksimovićNo ratings yet

- 365 Guitars, Amps & Effects You Must Play: The Most Sublime, Bizarre and Outrageous Gear EverFrom Everand365 Guitars, Amps & Effects You Must Play: The Most Sublime, Bizarre and Outrageous Gear EverNo ratings yet

- Guitar Shapes Navigator: Measuring the shapes of the guitar and the positions of its elementsFrom EverandGuitar Shapes Navigator: Measuring the shapes of the guitar and the positions of its elementsNo ratings yet

- Improving Well Placement With Modeling While Drilling: Daniel Bourgeois Ian TribeDocument0 pagesImproving Well Placement With Modeling While Drilling: Daniel Bourgeois Ian TribeidscribdgmailNo ratings yet

- NOV Drilling Simulator: Presented by Tore BergDocument18 pagesNOV Drilling Simulator: Presented by Tore BergidscribdgmailNo ratings yet

- NTM Res SimDocument0 pagesNTM Res SimidscribdgmailNo ratings yet

- Studio One Reference ManualDocument262 pagesStudio One Reference ManualidscribdgmailNo ratings yet

- PG DirectX Plugins READ MEDocument2 pagesPG DirectX Plugins READ MEidscribdgmailNo ratings yet

- Studio One Mackie Control SupportDocument5 pagesStudio One Mackie Control SupportidscribdgmailNo ratings yet

- ReadmeDocument4 pagesReadmeidscribdgmailNo ratings yet

- String Machines For Sampler Kontakt and EXSDocument3 pagesString Machines For Sampler Kontakt and EXSidscribdgmailNo ratings yet

- 8dio Epic Dhol Ensemble Read MeDocument8 pages8dio Epic Dhol Ensemble Read MeidscribdgmailNo ratings yet

- Installation InstructionsDocument2 pagesInstallation InstructionsidscribdgmailNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Facies Concepts, Continued: Interpreting FaciesDocument28 pagesIntroduction To Facies Concepts, Continued: Interpreting FaciesidscribdgmailNo ratings yet

- Philips MCM2300 Ver.3.0Document23 pagesPhilips MCM2300 Ver.3.0Alejandro Méndez MasdeuNo ratings yet

- Agilent 86205A-B and 86207ADocument4 pagesAgilent 86205A-B and 86207Amarco cNo ratings yet

- Grundig Yacht Boy 400 Lowres 1 enDocument5 pagesGrundig Yacht Boy 400 Lowres 1 enCarl RadleNo ratings yet

- KA2201Document4 pagesKA2201Shriniwas SalunkeNo ratings yet

- Foster WF-100k FAQDocument2 pagesFoster WF-100k FAQivoloviNo ratings yet

- JBL C200SI Spec Sheet English PDFDocument2 pagesJBL C200SI Spec Sheet English PDFSui muiNo ratings yet

- Pioneer Deh-P5450 User ManualDocument112 pagesPioneer Deh-P5450 User ManualLuke Job100% (1)

- Sony Ta Ve800gDocument181 pagesSony Ta Ve800gzarigueiaNo ratings yet

- CubaseDocument2 pagesCubaseJohn Alexander Contreras RuizNo ratings yet

- 10-Channel Mixer Preamplifier: DescriptionDocument2 pages10-Channel Mixer Preamplifier: DescriptionAhmed Shek HasanNo ratings yet

- Alcons-LR14-120-tech-specs 2Document2 pagesAlcons-LR14-120-tech-specs 2h2hpzcpg26No ratings yet

- Behringer Microphone PreamplifierDocument2 pagesBehringer Microphone Preamplifier'Dg NamuNo ratings yet

- Audio Calculator 1.73Document9 pagesAudio Calculator 1.73GUINo ratings yet

- Stereo Cassette Deck: TC-WE675 TC-WE475Document24 pagesStereo Cassette Deck: TC-WE675 TC-WE475marsan1708No ratings yet

- Aiwa Line PDFDocument2 pagesAiwa Line PDFFabrizio ForghieriNo ratings yet

- Ev Px2181 PDFDocument2 pagesEv Px2181 PDFKateNo ratings yet

- Philips DVP 720 SADocument41 pagesPhilips DVP 720 SAAmal Kumar DeNo ratings yet

- Scarlett 2i4 User GuideDocument18 pagesScarlett 2i4 User GuideSebastián TrepodeNo ratings yet

- Cr4Bt - Cr5Bt: Owner'S ManualDocument16 pagesCr4Bt - Cr5Bt: Owner'S ManualJuan Carlos ApacllaNo ratings yet

- Philips 6-IE550/ V Interstage Slope EqualizersDocument4 pagesPhilips 6-IE550/ V Interstage Slope Equalizersjose angel guzman lozanoNo ratings yet

- Soundsysem Aktif BMB 15: Mixer Yamaha 12 Channel Mg12Xu SpecificationDocument4 pagesSoundsysem Aktif BMB 15: Mixer Yamaha 12 Channel Mg12Xu SpecificationCecep HeryanNo ratings yet

- Roving Rostrum P.A. Models S132A: Portable Public Address SystemDocument2 pagesRoving Rostrum P.A. Models S132A: Portable Public Address SystemElla MariaNo ratings yet

- What Caps Your Amp UsesDocument5 pagesWhat Caps Your Amp UsesJong Jin KimNo ratings yet

- IMD UbaDocument12 pagesIMD UbaWalter RossiNo ratings yet

- Home Theater Speaker System: Simply CinemaDocument20 pagesHome Theater Speaker System: Simply CinemaMario Alberto Gonzalez PeñalverNo ratings yet

- Product Range Brochure 0222r BrochureDocument40 pagesProduct Range Brochure 0222r BrochureFifanNo ratings yet