Machaut-De Toutes Flores

Machaut-De Toutes Flores

Uploaded by

mluisabalCopyright:

Available Formats

Machaut-De Toutes Flores

Machaut-De Toutes Flores

Uploaded by

mluisabalCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Machaut-De Toutes Flores

Machaut-De Toutes Flores

Uploaded by

mluisabalCopyright:

Available Formats

If the surviving sources are at all representative, then De toutes flours (B31) was

one of Machaut's most widely disseminated songs. Not only is it contained in

all but the earliest of the collected `Machaut manuscripts' but it is also known

from seven other sources from the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries.

1

Although it is perhaps all too easy automatically to equate such relatively

abundant survival with popularity, it seems likely that this song was more

widely known than most of Machaut's output. One of the reasons for this is the

poetic text detailing the lover's angry plea that Fortune not destroy his `rose'

which is concerned with two extremely popular late-medieval themes: the

action of Fortune and the image of the beloved as a rose. The poetic text of B31

appears without music only in the unnotated music section of the collected

Machaut manuscript M (Paris, Bibliothe que Nationale, fonds franc ais 843).

Unlike the other Fortune poems, Il mest avis (B22) and De Fortune (B23), to

which it is linked both thematically and through shared diction and keywords,

B31 is not in Machaut's unnotated lyric collection, the Loange des dames. All

three Machaut musical balades that set texts concerning Fortune are present

outside the core Machaut sources in manuscripts of assorted songs, and all are

copied with extra or alternative voice parts.

2

All three are present in PR along

with an anonymous balade based on B23. In addition to its having an added

triplum in PR, B31's music was well-known enough to merit an instrumental

arrangement in Fa, alongside other examples of songs that have been identified

(for reasons of transmission) as a core `international' repertory.

3

Using a few textually difficult moments in B31, this article shows how an

analysis oriented by (but not limited to) medieval counterpoint teaching can

assist in text-critical matters. The overall tonal planning of the song has been

considered by Jehoash Hirshberg, Peter Lefferts and Yolanda Plumley, and the

piece has recently been thoroughly analysed in this and other details by Sarah

Fuller.

4

However, two small but related moments in the song present

particular textual problems. Their discussion by previous commentators will

provide a context for subjecting B31 to further examination.

Firstly, the marking of the cantus b in bar 15 with a hexachordal fa sign ([)

has variously been treated as an error (Fuller), used to support theories of

hexachordal approaches (Hirshberg), compositional exceptionality (Hirshberg

and Brothers), and to refute counterpoint-based understanding of musica ficta

Music Analysis, 19/iii (2000) 321

Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 2000. Published by Blackwell Publishers, 108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JF, UK

ELIZABETH EVA LEACH

INTERPRETATION AND COUNTERPOINT: THE CASE OF GUILLAUME

DE MACHAUT'S DE TOUTES FLOURS (B31)

and analytical approaches with a basis in fourteenth-century theory (Brothers).

Secondly, the appearance of an unusual dissonance between the cantus and

contratenor in the final few bars of the B section (the section before the refrain,

in bar 42) has been explained both as an early instance of word painting

(Wolfgang Do mling) and as a further index of compositional exceptionality

(Fuller). Both this dissonance and another potential contratenor-cantus (Ct-

Ca) dissonance slightly earlier in the same phrase (bar 40) will be discussed in

terms of what they might tell us about scribal and compositional priorities and

the modern interpretation of the normative-exceptional dialectic in relation to

Machaut's compositional practice.

The basic premise of this article is that analysis grounded in the tools

provided by medieval counterpoint teaching can reveal the extent of the

stability of the musical text of medieval songs. Whilst, as with B31, a medieval

song may be available in a varied number of voice parts, the added voices

depend to a great extent on a perception of, in this case, a three-part original as

being fixed in terms of relative pitch, poetic text and overall rhythmic pacing,

but flexible in terms of individual ornamental rhythmic figuration, text

underlay and its ability to support additional parts.

5

Brothers, arguing against a systematic application of ficta in line with prin-

ciples of counterpoint, and Hirshberg, arguing in favour of a hexachordally-

based modal understanding of tonality in Machaut, have both given the

example of one cadence in Machaut's De toutes flours B31 where a notated

accidental seems to contradict the inflection normally associated with a 68

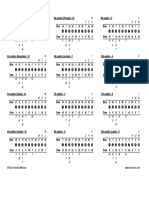

sequence of sonorities. Ex. 1 outlines the source situation against a modern

transcription of the first 16 bars of the piece. Fuller summarises the situation,

outlining two possibilities:

. . . at the end of phrase two, on vergier (breve 15), a notated B flat in the cantus

in two principal sources [Vg and A] contradicts the normal inflection (major

sixth D-B natural to octave C) expected at a cadence and specified at other C

endings in this song. In other copies where B flat stands as a `signature' in the

cantus, the flat is not specified. Trained performers . . . would surely sing B

natural to provide the conventional cadence progression, to fulfil the resolution

of the B natural at breve 14, and to be consistent with the other C cadences in

the piece. Does the notated B flat on vergier signify an express desire on

someone's part to override the conventional performance mode, or is it a scribal

lapse, a premature indication of a restored `signature' B flat? Although a good

case can be made for the second position, based on specific disposition in the

two principal sources, patterns of voice-leading and Machaut's normal practice

elsewhere, the other view cannot be completely ruled out.

6

Fuller's two possibilities (shown as Ex. 1a and Ex. 1c respectively) may be

joined by a third (Ex. 1b) in which the hexachordal sign is interpreted as

implying a knock-on effect in the tenor so that the tenor voice itself makes the

Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 2000 Music Analysis, 19/iii (2000)

322 ELIZABETH EVA LEACH

T

8

G Vg A FP

G Vg A

FP Pit

Ct

8

Ca

G Vg A FP Mod Pit

9

8 na

12

voitt de

G Vg A E

FP Mod

tous fruis

E

2. En mon

G Vg A

ver

16

gier fors

8

8

8

T

Ct

Ca

4 8

( )

( )

Pit

Mod

Mod

1. De

tou tes flours

G Vg A FP Mod Pit

Ex. 1 De toutes flours (B31), bars 116

fruis 2. En mon ver gier

Ca

T

8

8

T Ca

8

Counterpoint

8

Ex. 1a Bars 1516 `at face value'

Music Analysis, 19/iii (2000) Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 2000

GUILLAUME DE MACHAUT'S DE TOUTES FLOURS 323

semitone approach instead of the cantus. These three possibilities will be

discussed below.

Ex. 1a interprets the manuscripts at `face value' as a case of a minor sixth

proceeding to an octave but avoiding the semitone movement of the directed

progression. This has been argued by both Brothers and Hirshberg, both of

whom seek to avoid marginalising or explaining away the idiosyncratic and

exceptional. Brothers quotes Fuller's summary of the situation (given above)

and concludes conversely that the `flat' is:

. . . interesting for two reasons: it `cancels' b-natural in the cantus of two

measures earlier, before this pitch has a chance to resolve to the implied c; and it

undermines the arrival on c in measure 16 by creating a whole step instead of a

half-step leading tone. It is easy to understand how the flat could have been

fruis 2. En mon ver gier

Ca

T

8

8

T Ca

8

Counterpoint

8

Ex. 1b Bars 1516 with semitone approach in the tenor

fruis 2. En mon ver gier

Ca

T

8

8

T Ca

8

Counterpoint

8

Ex. 1c Bars 1516 with semitone approach in the cantus

Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 2000 Music Analysis, 19/iii (2000)

324 ELIZABETH EVA LEACH

dropped by a skeptical scribe (and Fuller shows herself to be one when she

drops it from her edition of a source that includes it). But the transmission of

the sign is not weak. It is firmly communicated by the principal sources, and it

is dropped only by the secondary sources . . . Rather than imagining, as Fuller

does, that trained singers knew how to `correct' unconventional cadences, I

imagine them being skillful in negotiating those cadences as written.

7

Brothers additionally invokes the text-critical principle of difficilior lectio potior

as a reason for accepting the b-fa in bar 15. His view accords substantially with

that of Hirshberg, who comments that `a cadence on c

0

without leading tone is

formed'

8

and that `Machaut's deliberate avoidance of the cadential progression

conflicted with the habit of modern performers of applying a cadential leading

tone'.

9

Although they ascribe the cliche respectively to the habits of medieval

theorists and modern performers, both Brothers and Hirshberg accept the b-fa

and argue that in bars 1516 Machaut deliberately manipulates a cadential

cliche . Objections to their view can be proposed under two related headings.

Firstly, taking notation at `face value' often actually means inappropriately

reading fourteenth-century notation by twentieth-century rules. Asserting, as

Brothers does, that a singer would have skilfully negotiated such cadences `as

written' falsely assumes that where the signs of fourteenth-century notation

resemble twentieth-century ones they can be read as if they meant then what

they would mean to us now.

10

Secondly, treating the directed progression as a

cliche is arguably an error of category. The directed progression is not just a

cliche , a normative formula to be abandoned at will, but a fundamental part of

a notational system very different from ours. The norms which composers may

entirely circumvent belong to continuous categories, such as form, style, types

of melody lines, types of interval succession, relationships between open,

closed and final cadences, and so on. These norms are established (by us)

retrospectively on statistical grounds (and all are discussed by Hirshberg to

argue for Machaut's exceptionality as a composer in these respects).

11

By

contrast, the semitone placement required by counterpoint is a discrete

quantity and beneath the notice of this kind of exceptionality it is more

fundamental than that. It is below the level of style which I would argue is

constituted exactly by the relationship of the musical surface to an underlying

conceptual basis in simple counterpoint.

12

The basis provided by counterpoint

teaching constitutes a meeting-point for composer and singer, referring every

singer to the tenor as the locus of musical articulation, and functioning as a

conceptual element in the composer's imagination. To achieve the pitches he

wants (both vertically and horizontally) the composer must manipulate the

content of each vocal line so that, by applying an understanding of a

`contrapuntal grammar' that they both share, the singer may perform the

desired pitches.

13

Music Analysis, 19/iii (2000) Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 2000

GUILLAUME DE MACHAUT'S DE TOUTES FLOURS 325

If this is a fair reading of the notational conventions within which composers

worked (and notation is part of a conceptual world for a composer), then all

perfect sonorities preceded by imperfect ones with at least one voice moving by

step should be interpreted as being approached by a semitone. Since such a

progression opens phrases as often as it ends them, the degree of closure is as

immaterial as (in fourteenth-century notation) is the presence or absence of an

accidental sign (except sometimes to specify which semitone, in cases where

both voices move by step). In our notation so-called `accidentals' are in fact

obligatory and must be specified. Thus, for us, a contrapuntal analysis of the

song precedes and enables the translation of the instructions for singing, in so

far as they are specific to pitch, into our notational-conceptual terms. When

this is done, the articulated surface of the music may then undergo further

analysis of a wide variety of types.

The placing of the semitone in the approach to perfect intervals receives

theoretical justification from many fourteenth-century sources. The author of the

Berkeley treatise, for example, writes that instructions to place semitones `are

often effectively present in b-fa b-mi even though they are not always written'.

14

However, the relationship between theory and practice is questioned by those

who understandably mistrust any systematic approach to this issue.

15

As

medieval composers appear to flout many theoretical recommendations, theory's

prescriptions may be thought incompatible with composers' realities. Theorists'

own disagreements and inconsistencies reinforce this view. However, Margaret

Bent has shown that the basic agreed tenets of the theory fit the music better than

its detractors would have us believe.

16

She comments directly on the issue of so

called `signatures', and accidental signs, saying that manuscript and theoretical

evidence only appear in conflict when seen from `the premise that absence of a

notated inflection or presence of a signature were prescriptive, as in modern

notation'.

17

Instead she interprets accidentals and `signatures' as weakly

prescriptive and apt to being overruled by contrapuntal necessity.

From evidence internal to Machaut's music itself it is possible to show that,

for him at least, the directed progression (the correct approach to perfect

intervals) should always involve a semitone approach. The evidence for this is

drawn from the way in which Machaut plays with, exploits and writes around

such progressions. Where both the imperfect and perfect elements necessary to

form a directed progression are present, Machaut will frequently delay the

imperfect element in some way, reduce its actual sounding value, or present its

two notes non-simultaneously (in hocket form, for example). Conversely he

uses the expectation created by mensurally strong, durationally long imperfect

sonorities to create forward movement, even in cases where immediate

resolution of these sonorities is absent.

18

Ex. 2 is taken from Machaut's two-part balade Pour ce que tous (B12). The

mi sign in bar 14 in all manuscripts serves to prevent the cantus singer singing

Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 2000 Music Analysis, 19/iii (2000)

326 ELIZABETH EVA LEACH

b-fa.

19

For a medieval singer, b-fa and b-mi are equally available recta pitches

and several factors may affect a singer's choice. Reading from a single part he

might well assume that his b above a held tenor d

0

at the end of a poetic line

when the next cantus note is c

0

would be a directed progression whose force

overrules that of mere melodic smoothness. Therefore, even in the absence of

any hexachordal sign and despite the melodic descent from e

0

-fa, he would

probably initially sing (the composer's desired) b-mi. Then, discovering that

the linear descent from e

0

-fa is not overruled by a directed progression, since

the tenor avoids its note of resolution (the expected c), a singer too clever for

his own good might employ the weaker default of considerations of line. To

avoid a linear tritone from e

0

-fa he would then sing b-fa on a second run-

through. To forestall this and signify that a juxtaposition of e

0

-fa and b-mi is

required and that the listener and not the singer should be caught out by

avoidance of the expected resolution, the mi is marked. That all sources

nevertheless feel the need to copy an accidental that in twentieth-century terms

is totally redundant, points once more to the fundamentally different

conception of pitch in the fourteenth-century.

This instance is one of many that could be cited to show that Machaut uses

held imperfect chords to set up expectations that, because the semitone

approach is not a stylistic convention (and therefore optional) but a notational

one (and therefore embedded conceptually in the compositional framework),

he can then exploit. Using the implication of a semitone inflection to tease the

listener depends on the directed progression's notational (and conceptual)

5. Mais qui vrai e ment sa roit 6. Ce

(All) ( ) ( ) (All)

C Vg B E G A

C Vg B G A C Vg B G A

8

8

Ca

T Ca

T

8

8

T Ca

Underlying counterpoint

x

(avoided)

Ex. 2 Pour ce que tous (B12), bars 1315

Music Analysis, 19/iii (2000) Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 2000

GUILLAUME DE MACHAUT'S DE TOUTES FLOURS 327

obligation. The expectational force of a held imperfect sonority would surely

be diminished if elsewhere a stepwise link between an imperfect sonority and a

perfect sonority were sometimes a matter of a whole tone that is, if the

directed progression were ever optional.

In bars 1516 of De toutes flours (B31), the dyad succession 68 occurs in the

tenor-cantus (T-Ca) duet, at a point of poetic articulation the caesura of line 2

8

8

mour 3. Car il

In: C Vg B G A E

C Vg G A

8

8

NOT

< >

G C

Ex. 3a On ne porroit (B3), ouvert ending and return to opening

da mi peut de si rer. 3. Et

G Vg B

C A E G Vg B

C A E G Vg B

In: C Vg B G A E

8

8

8

8

8

< >

8

< >

8

8

NOT

Tr

Ca

Ct

T

T Ca

T Ct

Ex. 3b Se quanque (B21), ouvert ending and return to opening

Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 2000 Music Analysis, 19/iii (2000)

328 ELIZABETH EVA LEACH

which parallels the similar cadence at the caesura of line 1 (bars 78). Under what

circumstances would the cantus singer be persuaded not to inflect his part when

the elements of a directed progression are presented clearly and adjacently (and

additionally cadentially)?

20

The closed and final cadences (the end of the A

section and the end of the song, respectively) are also 68 progressions to the c

octave, approached in the cantus from b-mi. I am sceptical that an accidental (and

notationally extraneous) sign in itself would be sufficient to break the pattern set

up by this framing, let alone to bring one aspect of the notational system (a

semitone inflection caused by the use of solmisation signs) into conflict with

another (a semitone inflection necessitated by counterpoint). Other songs suggest

that in order to notate the succession of two dyads that might have formed a

directed progression but without the necessary semitone movement in either part,

Machaut prevents stepwise voice-leading by crossing the voices. This avoids a

semitone connection between the individual elements of the two dyads in any

single voice. An example drawn from On ne porroit (B3) will illustrate this. Many

of Machaut's open endings lead back by directed progression to the opening

sonority, some of which require a ficta note and some of which simply encourage

a certain recta choice.

21

However, in B3 the ouvert sonority <a-c

0

> that appears

to augur one resolution (to b-fa unison), actually proceeds to g5 without a

semitone (see Ex. 3a).

22

Similarly, in Se quanque (B21, Ex. 3b), that the Ca is

below the T for the ouvert sonority <e-g> prevents a ficta adjustment of the Ca

e, because the opening sonority d8, whilst a resolution of the sonority e3, is not

presented as such in terms of its voice-leading. Neither voice moves by step: the

cantus leaps a seventh from e to d

0

and the tenor falls a fourth from g to d.

23

The evidence gleaned from the use of expectation-building imperfect

sonorities is reinforced by the use of voice-crossing to write around the

inflection of the semitone, both implying that the directed progression is not

just a singerly practice but a notational-conceptual one that cannot simply be

cancelled by an accidental sign but has to be compositionally avoided. If

Machaut had wanted to break the pattern of semitone approaches to the c

octave in balade 31, he could (and arguably, to be entirely clear and not run the

risk of subsequent scribal normalisation, would have had to) have disposed the

relevant notes differently between the voices. I therefore reject the reading of

Ex. 1a, which may be discounted from the possibilities available, and propose

that some kind of directed progression, complete with semitone, occurs in bars

1516, and that the fa sign must therefore mean something else.

*

One possible interpretation of the b-fa sign (Ex. 1b) is that it implies a tenor d-

flat, an inflection that might be confusing were it to be signed directly. If sight-

reading, then the cantus singer might solmise the notation as in the now-

Music Analysis, 19/iii (2000) Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 2000

GUILLAUME DE MACHAUT'S DE TOUTES FLOURS 329

rejected Ex. 1a b-fa c but both tenor and cantus singers would be aware that

the perfect sonority the octave c had been approached incorrectly. In

general, a counterpoint inflection is more likely to be in the cantus voice, but

here the sign in the cantus voice tells the cantus singer not to inflect his part

and thus implies that the tenor singer should provide the semitone. Musically

this would be highly significant for the piece. Setting up two different

solmisations of the same imperfect sonority in approaches to the most

important cadential goal of the piece would be an `exceptional' but not

unprecedented stylistic feature. It occurs, for example, in Riches damour (B5),

connecting the end of the first poetic line to the beginning of the second. Ex. 4

shows the manuscript situation.

24

What would otherwise be a simple matter of

a directed progression involving the tenor choice of the recta note b-fa over b-

mi, is complicated by the marking of the tenor b with a hexachordal mi sign in

all sources. The meaning of the sign is clarified for twentieth-century eyes in

three of the sources: the earliest (C); the one most closely associated with

Machaut (A); and the one that is probably posthumous but that is in the earlier

two-column format and that, arguably, transmits some early texts (G). Instead

of being an avoidance of the directed progression (as the modern collected

editions would have us believe), the mi sign placed in the cantus in bar 14

reveals that the directed progression is to be effected by the very unusual ficta

note d-mi. That the cantus d

0

is not marked with a mi sign in some of the

sources, but the tenor b is marked in all of them, strongly suggests that, far

from the hexachordal sign being able to deter singers from correctly

8

8

8

men di ans da mi e 2. Po vres des poir

C Vg B E A G

C G A

C Vg B E A

15 10

Ca

T

T Ca

< >

8

Underlying counterpoint

Ex. 4 Riches damour (B5), bars 1017

Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 2000 Music Analysis, 19/iii (2000)

330 ELIZABETH EVA LEACH

approaching a perfect sonority by preventing a semitone movement, the

marking of the tenor alone is sufficient to `notate' the d

0

-mi because of the

ingrained `contrapuntal grammar' of placing semitones in a correct approach to

perfect consonances. This piece shows that the very prescription inherent in

the principle of nearest approach, which raises objections in those opposed to

its systematic application, allows composers to do strange and idiosyncratic

things. Exceptional and unusual lines and harmony occur because of, and not

despite, the necessity for semitone placement in such sonority successions. In

B5, observing the rules of counterpoint is more important more fundamental

than avoiding an augmented leap or an unusual ficta note. Having negotiated

the correct but unusual solmisation (which might take singers two attempts),

the singers are wittily applauded by the text as they pronounce the correct

solmisation syllable `mi' to their held notes in bar 14, where it forms part of the

first rhyme word of the first line of the first stanza `damie'.

25

Thus there are precedents for the argument that a tenor d-fa is implied by

the cantus sign in bar 15 of B31. To my knowledge, no-one has made this

suggestion, although it would be more consistent with an understanding of

fourteenth-century cadences and counterpoint than taking the sign at face

value as a total avoidance of semitone movement. In the context of this article,

Ex. 1b forms one of two possible readings. However, I shall argue below that it

is one that, while possible, does not seem likely, because it breaks an otherwise

regular pattern of cadences in B31. In the larger musico-poetic context of the

balade as a whole, this regularity makes possible an extensive and elaborate

game that will be examined in the next section. The other balades in which

Machaut uses hexachordal signs in one part to bring about unusual ficta in

another, lack such pattern and have a more diverse tonal logic within which the

differently solmised approach to the same perfect sonority is meaningful.

*

The final interpretation (and the second of two that preserve the semitone

approach to c8) is that the cantus `ignores' the fa sign and approaches bar 16's c

0

fromb-mi. This means that the fa sign in bar 15 should be omitted from modern

editions, but this does not make it an error in fourteenth-century terms. If, as I

am arguing, its lack of relevance to the note immediately following would have

been contextually clear, then this implies that the sign has a more general

default meaning. This is the implication behind the omission of the sign from

both Leo Schrade's and Sarah Fuller's editions. As Fuller states, `a good case

can be made [for omitting the fa sign] based on specific disposition in the two

principal sources'.

26

The `specific disposition' referred to seems to allude to the

layout of the sources. Machaut manuscript C has a two-column format that

implies that this was the earlier layout. Although a late source, G is also copied

Music Analysis, 19/iii (2000) Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 2000

GUILLAUME DE MACHAUT'S DE TOUTES FLOURS 331

in a two-column format; all the other manuscripts are in single columns.

27

The

Machaut sources all have an initial fa sign in the cantus that is not repeated at

the start of every line.

28

Signature or default signs occurring at the beginning of

a line or column in a two-column format are often copied at the same musical

point at least half the time now visually mid-line in later sources, to become

so-called `floating signatures'. As the original sign was a `signature', a weakly

prescriptive default setting (telling the singer that, except where counterpoint

demands otherwise, b-fa rather than b-mi should be selected), the repositioning

of the sign when subsequently copied into the one-column format is usually of

little consequence.

B31 is not present in the other two-column source, C. In manuscript G,

however, the fa `signature' of B31 occurs not just at the beginning of the first

line, but also at the top of the second column of the folio (see Ex. 5). The

column break happens to precede the note b (bar 15), which therefore follows

directly after the restatement of what the mis-en-page suggests is merely a

global (default) b-fa after the clef at the top of the column. This visual context

would aid the singer's recognition of the sign as a default `signature' rather

than as an immediately applicable local sign.

Default settings were alterable locally for directed progressions. Just as the

initial (`signature') b-fa does not affect the b-mi contrapuntally required in bar

7, neither does the hexachordal fa sign, which represents a global default,

overrule the contrapuntal necessity of b-mi in bar 15, particularly when the

musical sense of the phrases is that the resolution to c8 in bars 1516 clearly

parallels the one in bars 78. On a first reading, a somnambulant fourteenth-

century singer might perhaps have been confused, but could subsequently have

correctly identified this `fa' sign as global, rather than local, in meaning. For

him, it is not an error as such it just means something else, a `something' that

such signs can no longer mean in our usage. In the later single-column sources,

this sign is copied immediately before the same note that now occurs mid-line,

where, to the modern eye at least, its positioning bestows upon it a value

greater than any in the original format. However, even here it is no more

specific in meaning it is still a global sign, restating a general default after the

`upset' of the b-mi (signed in bar 14 and not inferable from counterpoint

alone). In a modern score, assisted by a strict bar's length acting of non-

signatures and a required following of signatures unless explicitly cancelled by

signs, the global/local distinction is much more tightly defined.

This reading implies almost the opposite of Brothers's and Hirshberg's

claim that the fa sign in bar 15 `cancels' the mi sign in bar 14. Instead, it is the

mi sign of bar 14 that temporarily suspends a default b-fa setting. For Brothers,

the cancelling of the b-mi annuls the expectation before it has time to resolve

and thereby `undermines the arrival on the c in measure 16 by creating a whole

step instead of a half-step leading tone'.

29

Reversing the direction of

Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 2000 Music Analysis, 19/iii (2000)

332 ELIZABETH EVA LEACH

Ex. 5 De toutes flours (B31) in MS G

Photographic reproduction by the Bibliothe que nationale de France.

Music Analysis, 19/iii (2000) Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 2000

GUILLAUME DE MACHAUT'S DE TOUTES FLOURS 333

cancellation, however, the b-fa default is explicitly suspended by the mi sign in

bar 14 because a deviation from the default is discouraged by the melodic line,

which does not proceed directly to the note of resolution, c

0

. After bar 14, the

default setting is restated in a few sources and, even though the note b follows

the fa sign immediately, it is sung mi because counterpoint considerations

overrule a default hexachordal solmisation, even one so adjacently stated.

30

In

B31, by coincidence, several sources happen to place the sign in this place,

which seems to lend it more authority. Such coincidence is hardly surprising

given the evidence for the interdependent copying of the Machaut

manuscripts, their possible derivation ultimately from a single authoritative

exemplar, and indeed by the sheer force of probability in such a large output.

The above interpretation (Ex. 1c) is supported by the notation of the piece

outside the collected Machaut sources. The cantus in these other manuscripts

notates the mi sign in bar 14 and does not notate b-fa in bar 15 because every

new staff line re-states a default (or signature) b-fa.

31

Invoking the philological

principle of difficilior lectio potior privileging a more unusual reading so as

not to marginalise idiosyncrasy Brothers interprets the reading of the

Machaut manuscripts (with locally notated b-fa in bar 15) as more difficult, and

therefore more likely to represent compositional exceptionality. The later non-

Machaut musical anthology sources (with no locally notated b-fa) are seen as

having been subject either to scribal hyper-correction or ignorance.

32

Although

generally a sound principle by which to distinguish authorial from scribal

initiative and older sources from more recent non-authorial circulations,

difficilior lectio potior requires that all readings considered should first be

possible. In a literary text, those readings deemed nonsense against a semantic

yardstick are discarded so as to avoid accepting errors in attempting to

privilege authorial exceptionality. I am arguing that the directed progression is

similarly a basic unit, whose positive, forward manipulation (as a creator of

expectation) relies on the impossibility of its negative manipulation, that is, its

abandonment. If desired, the effect that abandoning the semitone approach

would have had in terms of sonority succession could be achieved by the

crossing of voices, but the semitone component of a directed progression is too

fundamental to be prevented by a sign alone. Counterpoint, therefore, almost

becomes to a musical text what semantics is to a literary one, and can help us

dismiss errors from the choice of possible readings.

Brothers' use of difficilior lectio potior is also influenced by a division of the

sources for B31 into two distinct and unequal groups: the primary sources (the

`Machaut manuscripts') and secondary sources (all other sources). Whilst such

a division may seem both obvious and useful, it merits closer scrutiny. As both

scribe and poet, Machaut has a dual authority in the context of the late-

medieval culture of the book.

33

Sylvia Huot has interpreted the scribal

ordering of manuscript collections in the thirteenth and early-fourteenth

Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 2000 Music Analysis, 19/iii (2000)

334 ELIZABETH EVA LEACH

centuries as an exercise of authority and an attenuated manifestation of

authorship.

34

The choice and order of items for a single codex can create

meanings additional to those of the individual items themselves, thereby

`establishing the affinities between scribal and poetic practices'.

35

Machaut

probably oversaw the copying of at least two of the codices which survive C

and A, the latter of which carries the famous index rubric `vezci lordenance que

G. de Machau wet quil ait en son livre' (behold the order that Guillaume de

Machaut wishes to have in his book).

36

Machaut's authority manifests itself

chiefly as the interest of a scribe in overall order. Whilst the Machaut

manuscripts are thus authoritative in terms of the additional means gained

from such overall order, copy-editing at the level of the individual piece or

poem was not part of Machaut's remit. Errors could and did enter the

transmission, and remain there, as Lawrence Earp has shown.

37

Furthermore,

in the Prologue to the later anthology MSS, Machaut personifies Musique as the

third child (and the younger daughter) of Nature, presented to him as one of

the technical means by which the content of his poems will be animated;

Machaut is identified by his younger contemporary Eustache Deschamps as a

poe te and not as a composer.

38

Thus, the prevailing aesthetic is more literary

than musical in our sense, something not true of the non-Machaut sources

which are not literary, but musical, anthologies. As John Na das has

commented about PR:

. . . even if gatherings 6 and 7 of the Reina Codex are not the ideal source for the

French repertory of the late fourteenth century, we might still appreciate the

fact that this section of the manuscript . . . may have transmitted certain features

of a composition properly and others incorrectly. The editor's quest need not be

for manuscripts that are on the whole more correct than others, but rather for

individual readings and even certain elements of readings, such as texting and

vocal scoring that are more correct.

39

The non-Machaut sources do not transmit the poetic texts fully and the pieces

are removed from their meaning-giving order. In this respect, much of

Machaut's meaning is lost. Preserved, however, is their musical substance.

Some non-Machaut manuscripts may therefore represent a specifically musical

tradition for Machaut's songs that might transmit certain elements more

reliably than the Machaut manuscripts themselves.

40

As Na das urges, only `[a]

careful codicological and paleographical study of the great late-medieval

anthologies of secular polyphony can form the proper basis for an analysis of the

readings they contain'.

41

As a general observation, those inflections required by

directed progressions are far less frequently signed in the non-Machaut sources

than in the Machaut manuscripts, whilst those which set general defaults

(`signatures') are more frequently used.

42

This could indicate that more singerly

knowledge is assumed outside the Machaut manuscript tradition than within it,

Music Analysis, 19/iii (2000) Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 2000

GUILLAUME DE MACHAUT'S DE TOUTES FLOURS 335

(after all, by the late fourteenth century these now-famous songs are imprinted

on singers' memories far more than at the point of the copying of the Machaut

manuscripts), and that therefore, as far as the music is concerned, the readings

of these sources are not to be dismissed lightly.

Simply inverting the importance of the two categories of manuscripts

transmitting Machaut's work runs the risk of both reinforcing the duality

between the two groups and participating in the same value-system, merely

basing `authenticity' a concept which is inappropriately value-laden on new

criteria. Although it is of obvious benefit to the musicologist that the Machaut

manuscripts have survived, a blanket ascription of power and authority to them

does not make sense for every last detail of the music, since it privileges a

literary musical aesthetic over an arguably more musical one (and a poietic one

over an esthesic one). The non-Machaut sources are central to the reception

history of Machaut's songs. Their witness to the lack of a hexachordal fa sign in

bar 15 is an important indicator of how this famous song was understood.

It is also possible to argue for the importance of the b-mi in bar 15 from an

analysis of the musico-poetic structure of B31. The whole song plays with a

clever poetic structure in which internal, caesural rhymes are privileged so that

the listener is disorientated as to the poetic (and, by extension, the musical)

structure.

43

Fuller finds that `[t]he formal regularity of the poetic stanza is . . .

quite upset in the musical setting' because `Machaut is far less concerned with

the balance of ten-syllable lines than with syntax and nuance of language'.

44

I

would argue, however, that the stanzaic regularity is not so much `upset' as

offset. As well as an undoubted `concern for syntax and nuance of language',

this offsetting is integral to an elaborate musico-poetic game which relies on

the exploitation of just such poetic regularity for its working.

The basic premise of the game is to suppress real rhyme words, to use

musical phrases to privilege caesural words, treating them as if they were

rhyme words, and to use the verse structure to confuse the listener as to when

the music finally makes poetic lines congruent with musical phrases. The

functioning of the game is allowed by the careful establishment of expectation

in the A section. Table 1 shows the text as sectioned by the music juxtaposed

with the formal poetic structure. The first musical phrase sets the first four

syllables of the first line up to the caesura of the first line at the word `flours'

that anticipates the real c-rhyme. The musical phrase is closed by a T-Ca

cadence to c8 in bar 8. The real a-rhyme at the end of the first line is internal to

the second musical phrase that sets the text from the caesura of line 1 to the

caesura of line 2. The a-rhyme appears on the b-mi of bar 14 and is thus

connected to and resolved by the caesural word of line 2, `vergier' in bar 16.

Significantly, `vergier' anticipates the real d-rhyme that will end line 7 and

which retrospectively will break up the succession of offset lines and

rhymes and force acknowledgement of the musico-poetic deception.

Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 2000 Music Analysis, 19/iii (2000)

336 ELIZABETH EVA LEACH

The beginning of the B section in Machaut's balades frequently a locus for

exploring novel or extreme elements of range, harmony and rhythm is where

the text-music game is most prominent. This verse form (one of Machaut's

favourites) has eight lines, seven of which are decasyllabic but one of which

the fifth line has only 7 syllables. This fifth line occurs at the beginning of the

B section and is set to a musical phrase that does not end until the T-Ca

cadence to c8 at the caesura of line 6. Although there are in fact 11 syllables in

this phrase, it is almost as if the musical phrase were coterminous with a full-

length (decasyllabic) text line as if the game of the A section has been

abandoned. The word at the end of this musical phrase (bar 37) is `amatir'. The

next musical phrase, which in reality sets the text from the caesura of line 6 to

the caesura of line 7, confirms the (false) perception of `amatir' as the end of a

line and a rhyme word (the pseudo c-rhyme), by ending with the word

`cueillir'. But, as the listener is now forced to acknowledge, something is not

right. The second T-Ca c8 cadence (bar 41) is metrically offset, it is overlaid

with a T-Ct directed progression creating an extreme dissonance (bar 42; see

below) which connects it to the remainder of the B section text. These final six

syllables of line 7 (bars 436) retrospectively reveal the true poetic structure of

the B section. These six syllables are separated from the body of the poem

thereby revealing the prior musico-poetic deception (and forewarning of the

deception that will be the cause for the narrator to think that Fortune has

plucked his rose).

The anticipation of the B section's rhymes in the A section's caesuras aptly

occurs only in the first stanza after this it would cease to be anticipation (the

real c- and d-rhymes already having happened). However, in the final stanza

the `fake' internal rhyme between the caesura of line 6 (bar 38) and that of line

7 (bar 42) involves the words `plour' and `tour' echoing firstly the c8 cadence

of the first phrase of the first stanza (`flours') which ushered in the start of the

musico-poetic deception. Because `flours' at the caesural cadence of the first

line foreshadowed the real c-rhyme, its `echo' in the caesuras of lines 6 and 7 of

the last stanza creates an identity between the fake c-rhyme and the real c-

rhyme. At a third run-through, when the deception might finally have been

untangled, this further layer of deceit and confusion is added, linking

Fortune's false `honnour' with `plour' (tears) and her honour's reality

`deshonnour' with the `faus tour' (false trick) that will cause the speaker's

rose to wither.

The musico-poetic parallel between bars 1316 and 3942 (which empha-

sises the second caesura of the A and B sections respectively) promotes more

purely musical similarities. The correspondence of their accidental signs

suggests strongly that they should be performed identically.

45

The b in bar 14

and its parallel in bar 40 are both helpfully marked with a hexachordal mi-sign,

because the recta choice for the mi is not prescribed by immediate localised

Music Analysis, 19/iii (2000) Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 2000

GUILLAUME DE MACHAUT'S DE TOUTES FLOURS 337

Table 1 The poetic text of B31 divided by musical phrases and cadences

Musical Text in musical units psuedo sonority Text in poetic units real sonority

Form pseudo rhymes/real rhymes rhyme real rhymes rhyme

Stanza I

A1 De toutes flours a = c c8 De toutes flours navoit et de tous fruis a d-b

navoit et de tous fruis en mon vergier b = d c8 en mon vergier fors une seule rose b d8

ouvert fors une seule rose b d8

A2 Gastes estois c8 Gastes estois li seurplus et destruis a d-b

li seurplus et destruis par fortune c8 par fortune qui durement soppose b c8

clos qui durement soppose b c8

B Contre ceste douce flour pour amatir c c8 Contre ceste douce flour c d-b

sa coulour et sodour mais se cueillir c c8 pour amatir sa coulour et sodour c g-b

le voy ou tresbuchier d d8 mais se cueillir le voy ou tresbuchier d d8

R Autre apres li jamais avoir ne quier d c8 Autre apres li jamais avoir ne quier d c8

Stanza II

A1 Mais vraiement c8 Mais vraiement ymaginer ne puis a d-b

ymaginer ne puis que la vertus c8 que la vertus ou ma rose est enclose b d8

B

l

a

c

k

w

e

l

l

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

t

d

.

2

0

0

0

M

u

s

i

c

A

n

a

l

y

s

i

s

,

1

9

/

i

i

i

(

2

0

0

0

)

3

3

8

E

L

I

Z

A

B

E

T

H

E

V

A

L

E

A

C

H

ouvert ou ma rose est enclose b d8

A2 viengne par toy c8 viengne par toy et par tes faus conduis a d-b

et par tes faus conduis eins est c8 eins est drois dons naturex si suppose b c8

drois dons

clos naturex si suppose b c8

B Que tu navras ja vigour damentir son c c8 Que tu navras ja vigour c d-b

pris et sa valour lay la moy donc (c) c8 damentir son pris et sa valour c g-b

quailleurs nen mon vergier d d8 lay la moy donc quailleurs nen mon vergier d d8

R Autre apres li jamais avoir ne quier d c8 Autre apres li jamais avoir ne quier d c8

Stanza III

A1 He fortune c8 He fortune qui es gouffres et puis a d-b

qui es gouffres et puis pour engloutir c8 pour engloutir tout homme qui croire ose b d8

ouvert tout homme qui croire ose b d8

A2 ta fausse loy c8 ta fausse loy ou riens de bien ne truis a d-b

ou riens de bien ne truis ne de seur c8 ne de seur trop est decevant chose b c8

clos trop est decevant chose b c8

B Ton ris ta joie tonnour ne sont c8 Ton ris ta joie tonnour c d-b

que plour c = c !

tristesse et deshonnour Se ti faus tour c = c ! c8 ne sont que plour tristesse et deshonnour c g-b

font ma rose sechier d d8 Se ti faus tour font ma rose sechier d d8

R Autre apres li jamais avoir ne quier d c8 Autre apres li jamais avoir ne quier d c8

M

u

s

i

c

A

n

a

l

y

s

i

s

,

1

9

/

i

i

i

(

2

0

0

0

)

B

l

a

c

k

w

e

l

l

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

r

s

L

t

d

.

2

0

0

0

G

U

I

L

L

A

U

M

E

D

E

M

A

C

H

A

U

T

'

S

D

E

T

O

U

T

E

S

F

L

O

U

R

S

3

3

9

directed progression and is, in fact, discouraged by both the global b-fa setting

and the local linear descent from a cantus figure turning around e

0

-fa (bars 13

and 39). The function of b-mi in both places is to extend the length of the

directed progression by exploiting the expectation that imperfect sonorities

create. To do this, the b-mi is needed a little sooner than is strictly inferable

from counterpoint rules which work with adjacent sonorities in simple

counterpoint.

46

The resolution sonority, c8, does not occur until the second

half of the breve (bar 41) and whilst Mod Pit and FP restate the default b-fa

immediately after it in bar 42, PR restates its fa sign immediately before the b-

mi in bar 41. Although a better musical case could be made for bar 41 than for

bar 15 (since the phrase is joined to the following one by an overlaid T-Ct

directed progression that might warrant the diffusing of the c8 arrival), to

apply difficilior lectio potior here would be somewhat perverse (and no editor

hints at such a practice, probably because it is only a case of one non-Machaut

source against others). If b-mi is to be accepted here (which no editor seriously

questions), then it is very likely that b-mi should also be sung in bar 15.

To summarise: the caesural c8 cadences of lines 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 and 7 acquire

value because c8 is the terminal section-end goal sonority. However, only

lines 4 and 8 of each stanza (made identical through `musical rhyme' the

occurrence of the same extensive closural passage to end both A2 with the

closed cadence and the refrain) have such a cadence at their end. Lines 2 and

7 have directed progressions whose resolution sonorities are the secondary

terminal goal d8. All other text lines have b-mi in the cantus and form an

imperfect sonority with the tenor (see Table 1). This is mostly d-b-mi, that

is, with the tenor note of the secondary terminal sonority (d8) but a sonority

of imperfect quality, making it both tonally `open' and contrapuntally

unstable. If lines 1 and 3 were to have b-fa in bar 15, then the patterning of

cadences, and in particular the paralleling of the caesuras of the A section

with the caesuras of the B section (which the A section caesura words also

anticipate in the real text line ends of the B sections), would be considerably

weakened for no real gain.

47

*

One further text-critical issue may now be approached. In bars 4042 there are

two striking Ct-Ca dissonances, one of which is caused by the cantus b-mi at

the end of line 6 (bar 40). Since this is the moment the offsetting game

disintegrates, it is a particularly climactic one. The musical phrase that starts in

bar 38 defines its opening with a directed progression in both tenor duets to e-

fa5/8 (bar 39), the contratenor sings b-fa. The contratenor then restates the b-fa

at the start of bar 40 as an ornament (effectively a `re-sounded' suspension) as it

descends to its contrapuntally essential note, f-mi, which conceptually occupies

Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 2000 Music Analysis, 19/iii (2000)

340 ELIZABETH EVA LEACH

bars 4041. This means that the b-fa of the contratenor's resolution, whilst

conceptually over by the end of bar 39, is actually still sounding when the

cantus's b-mi for its progression to c

0

is first sounded (bar 40) (see Ex. 6a). The

only alternative would be for the contratenor to make a chromatic movement

from b-fa to b-mi between bars 39 and 40. Although similar chromatic

movements occur at the level of simple counterpoint in some of Machaut's

other songs, they are always carefully disguised (and thereby facilitated?) by

surface ornamentation, possibly pointing to their unacceptability or difficulty

at a surface level. Although the contratenor-cantus relationship is not bound by

the rules of counterpoint, since each has a discant relationship `independently'

with the tenor and not with each other, and although working within a dyadic

harmonic system, Machaut has a clear concern for overall sonority (as is

evinced by his four-part writing).

48

Were the b-fa longer and also, like the

cantus's b-mi, part of the underlying simple counterpoint with the tenor at this

point, this would offer grounds on which to suggest emendation. However, the

dissonance lasts only a minim and the contratenor b-fa is no longer a

contrapuntally essential note of the T-Ct duet when its sounding forms the

dissonance with the cantus. Thus, the brief b-fa-b-mi dissonance seems to be

plausible and stylistically possible.

49

This brief but extreme dissonance may serve an added function. It may

prepare for (and retrospectively be revealed not to be an error by) the following

and more lengthy Ct-Ca dissonance in bar 42 see Ex. 6b. Here both tenor

duets have directed progressions, which are offset so that the T-Ca resolution

37 40

Pit

Mod

G Vg A FP G Vg A FP E

G Vg B A

FP Mod

Mod

Pit

8

8

8

tir sa coulour et so dour 7. Mais se cueil lir le

8

8

T Ca

T Ct

a b

Ex. 6 De toutes flours (B31), 3842

Music Analysis, 19/iii (2000) Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 2000

GUILLAUME DE MACHAUT'S DE TOUTES FLOURS 341

to c8 is overlaid with a tension chord for a T-Ct progression to B-fa8. This

would work unremarkably if it were not for the cantus's falling back to g just as

the contratenor rises to a, giving a dissonance of a second for the whole breve

unit (bar 42). As this cantus note is not strictly part of the directed progression,

it would be possible to emend it to f or g. Fuller writes that:

The preparatory element (breve 40) is a third, not a sixth. The sixth arrives but

its resolution falls early, on the second part of breve 41, before the phrase ends.

The cantus subsequently drops to rest on G, seemingly oblivious of the

contratenor a. This (breve 42) is the point of utmost dissonance and tension in

the song, a moment due not to sonority and pitch relations alone, but to the

rhythmic framework within which they are cast.

50

In a footnote, Fuller considers the dissonance in bar 42 to be augured by the

brief but identical Ct-Ca sonority in bar 15 (its parallel phrase) although this is

much shorter and clearly part of the decoration of the consonances forming the

underlying simple counterpoint. That all types of sources contain this

dissonance furthers editorial reluctance to emend this dissonance. The poetic

text has also been cited in support of the dissonance. Wolfgang Do mling, for

instance, considers the dissonance to be explained by the word `cueillir' which

may be additionally signified by the downward leap of a fourth in the cantus.

He also notes that the dissonance is unusual (unprecedented?) in Machaut's

works organised at the breve level.

51

Perhaps there is some sort of localised

notional organisation at the modus level here, created by the stringing out over

almost two breves (and several tenor notes) of the cantus b-mi in bar 40 before

its resolution in the second half of bar 41 (arguably resembling the similar

instance in bars 1415).

*

Analysis led by counterpoint considerations has helped fix the musical text,

both in the sense of stabilising those of its unusual elements that are part of the

design, and in the sense of adjusting those that can be shown to merit further

interpretation or emendation. It is worth noting that, in fact, nothing has been

identified as an error in fourteenth-century terms, although to signify the

sounds implied in the fourteenth-century notation, ours requires different ones

to be added or theirs to be omitted. The analytical premises have, in their

working out, revealed much about the interpretation of signs and the

acceptability of levels of dissonance in this style. I have argued that the very

directionality central to the so-called directed progression means that it can

only be manipulated in one direction. Therefore, those instances that seem to

us to evade the necessary semitone either imply the exceptional use of an

unusual ficta note to provide the semitone or are simply misleading when

Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 2000 Music Analysis, 19/iii (2000)

342 ELIZABETH EVA LEACH

transcribed into a modern score, translated into which context they warrant

omitting (or moving) to render their original meaning. As a basic part of the

notational-conceptual framework, simple counterpoint is useful in identifying

inflections not given a separate sign in the original notation. It is against basic

counterpoint that we can describe the individuality and exceptionality of

Machaut's songs in terms of their dissonance treatment and, in particular, the

dissonances permissible between voices not in discant relationship. Although it

may not be sufficient for all our analytical needs, it is a necessary starting point

because of the role it serves in generating the text for analysis, that is, the piece

in our notational-conceptual translation. Counterpoint does not prevent

exceptionality but, rather, provides a framework within which it is made

possible. Exploiting its possibilities and playing imaginatively within its

parameters is Machaut's skill at which (to the extent that these groups are

separate) singers and listeners alike must marvel.

Appendix A

Key to Musical Examples

Abbreviations

T Tenor

Ct Contratenor

Ca Cantus

Tr Triplum

The musical examples aim to give some idea of the manuscript situation for

each passage. Accidentals marked on the staff carry above them the sigla of the

sources in which they occur. No accidentals carry the force of a modern

signature. Instead, all accidentals last the bar's length imposed by the modern

bar line. A circled siglum above an accidental indicates a start-of-line

placement for the sign in that particular source. Editorial accidentals realising

contrapuntal semitones are indicated above the staff.

The contrapuntal analysis is shown in an arhythmic format. In the initial

parsing, dissonances are shown with crossed noteheads. In both the initial

parsing and the analysis of underlying simple counterpoint, consonances are

shown with filled noteheads for imperfect consonances (thirds, sixth and their

compounds) and empty noteheads for perfect sonorities (unisons, fifths,

octaves and their compounds).

The bar numbers for B31 accord with those in Fuller. The bar numbers for

other examples accord with those in Schrade.

Music Analysis, 19/iii (2000) Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 2000

GUILLAUME DE MACHAUT'S DE TOUTES FLOURS 343

Editions

Ludwig: Ludwig, Friedrich (ed.), Guillaume de Machaut: Musikalische Werke, 4

vols. (Leipzig: 192654).

Schrade: Schrade, Leo (ed.), The Works of Guillaume de Machaut, 2 vols.,

Polyphonic Music of the Fourteenth Century (Les Remparts, Monaco:

L'Oiseau-Lyre, 1956).

Fuller: Fuller, Sarah, in Mark Everist (ed.), Models of Musical Analysis (Oxford:

Blackwell, 1992), pp. 5961.

NOTES

1. De toutes flours (B31) is in the Machaut manuscripts G (Paris, Bibliothe que

Nationale, fonds franc ais 225456), E (Paris, Bibliothe que Nationale, fonds

franc ais 9221), Vg (New York, Wildenstein Collection [no shelfmark]) and its

copy B (Paris, Bibliothe que Nationale, fonds franc ais 1585), A (Paris,

Bibliothe que Nationale, fonds franc ais 1584) and its copy Pm (New York,

Pierpont Morgan Library, M 396). With the exception of E, the song appears in

three parts with contratenor. In addition E transmits a triplum. The other

sources for B31 are the late fourteenth-century Florentine musical anthology

manuscript FP (Florence, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, Panciatichiano 26), the

early fifteenth-century Italian manuscript Pit (Paris, Bibliothe que Nationale,

fonds italien 568) and the fifteenth-century settentrional source Mod (Modena,

Biblioteca Estense, a.M.5.24). It is listed in the index which survives from the

fourteenth-century royal manuscript Tre m (Paris, Bibliothe que Nationale,

nouvelles acquisitions franc aises 23190), appeared in the German source Str

(Strasbourg, Paris, Bibliothe que Municipale, M. 222 C. 22, a MS destroyed in a

fire in 1870 and accessible only through a partial transcription made by

Coussemaker) and found in an instrumental intabulation in the Ferrarese source

Fa (Faenza, Biblioteca Communale, 117) from the second decade of the fifteenth

century. It is transmitted in the sixth fascicle of the Veneto source PR (Paris,

Bibliothe que Nationale, nouvelles acquisitions franc aises 6771) with an added

triplum which is the same in all but minor details as that in E. These sigla

concord with those in Lawrence Earp, Guillaume de Machaut: A Guide to

Research (New York: Garland, 1995), see especially Ch. 3. The balade is also

cited in an anonymous fifteenth-century German treatise, ed. Martin Staehelin,

`Beschreibungen und Beispiele musikalischer Formen in einem unbeachteten

Traktat des fru hen 15. Jahrhunderts', Archiv fu r Musikwissenschaft, 42 (1989),

pp. 220.

2. For a discussion of these and other poems by Machaut on the theme of Fortune,

see Leonard W. Johnson, Poets as Players: Theme and Variation in Late Medieval

Poetry (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1990), pp. 4158. For a

discussion of these songs and comments on Johnson's readings, see also Elizabeth

Eva Leach, `Fortune's Demesne: The Interrelation of Text and Music in

Machaut's Il mest avis (B22), De fortune (B23), and Two Related Anonymous

Balades', Early Music History, 19 (2000), forthcoming.

Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 2000 Music Analysis, 19/iii (2000)

344 ELIZABETH EVA LEACH

3. See the persuasive arguments of Reinhard Strohm in his `The Ars Nova

Fragments of Gent', Tijdschrift van der Vereniging voor Nederlanse Muziek-

geschiedenis, 34 (1984), pp. 11723.

4. Jehoash Hirshberg, `Hexachordal and Modal Structure in Machaut's Polyphonic

Chansons', in J. W. Hill (ed.), Studies in Honour of Otto E. Albrecht: A Collection

of Essays by His Colleagues and Former Students at the University of Pennsylvania

(Kassel: Ba renreiter, 1980), pp. 357; Peter Lefferts, `Signature Systems and

Tonal Types in the Fourteenth-Century French Chanson', Plainsong and

Medieval Music, 4/ii (1995), p. 133; Yolanda Plumley, The Grammar of 14th

Century Melody: Tonal Organization and Compositional Process in the Chansons of

Guillaume de Machaut and the Ars subtilior (New York: Garland, 1996), pp. 18

19, 174; and Sarah Fuller, `Guillaume de Machaut: De toutes flours', in Mark

Everist (ed.), Models of Musical Analysis: Music before 1600 (Oxford: Basil

Blackwell, 1992), pp. 4165. The triplum, seemingly added at a later stage by

someone other than Machaut, is briefly discussed in Wolfgang Do mling, Die

Mehrstimmigen Balladen, Rondeaux und Virelais von Guillaume de Machaut

(Tutzing: Hans Schneider, 1970), pp. 7980, but is not central to Fuller's analysis.

5. Even the keyboard arrangement in Fa, which may appear to be a two-part

reduction of B31 in major prolation, has been shown to use elements of the

contratenor part in its compound upper part and to preserve the basic breve

harmonic pace, despite the different figuration available in the new mensuration;

see Jane E. Flynn, `The Intabulation of De toutes flours in the Codex Faenza as

Analytical Model' (unpublished paper read at the Medieval and Renaissance

Music Conference, York, 1998).

6. Fuller, `Guillaume de Machaut: De toutes flours', p. 57.

7. Thomas Brothers, Chromatic Beauty in the Late Medieval Chanson: An

Interpretation of Manuscript Accidentals (Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, 1997), pp. 116, 117.

8. Hirshberg, `Hexachordal and Modal Structure', p. 35.

9. Jehoash Hirshberg, `The Exceptional as an Indicator of the Norm', in U. Gu nther,

L. Finscher and J. Dean (eds.), Modality in the Music of the Fourteenth and

Fifteenth Centuries (American Institute of Musicology: Ha nssler, 1996), p. 54.

Hirshberg asserts that the `b rotundum, which cancels b quadratum, is designated in

bar 15 in all Machaut Repertory manuscripts as well as in P[it], Reina [PR] and

FP', (p. 53). However, having examined PRand seen microfilms of FPand Mod, I

concur with Brothers' representation of the situation, that is, that the sign is not

present in these `secondary' sources.

10. Margaret Bent has written persuasively against making such an anachronistic

assumption. See Margaret Bent, `Diatonic Ficta', Early Music History, 4 (1984),

pp. 148; `Editing Early Music: The Dilemma of Translation', Early Music, 22/

iii (1994), pp. 37392; `Diatonic ficta Revisited: Josquin's Ave Maria in Context',

Music Theory Online (September 1996) (mto.96.2.6.bent.tlk); and `The Grammar

of Early Music: Preconditions for Analysis', in Cristle Collins Judd (ed.), Tonal

Structure in Early Music (New York: Garland, 1998), pp. 1559.

Music Analysis, 19/iii (2000) Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 2000

GUILLAUME DE MACHAUT'S DE TOUTES FLOURS 345

11. Exceptionality in Machaut is often also recognised from elements that can be

retrospectively construed as progressive. See Hirshberg, `The Exceptional as an

Indicator of the Norm', especially p. 64.

12. Musical notation either represents performance actions that produce certain

sounds or represents the sounds themselves through conventional graphic-sonic

analogies. What, in twentieth-century terms, are unsigned accidental inflections

are, in fourteenth-century terms, no less explicit than those which carry a

hexachordal sign both depend on the singer's knowledge of the relationship

between representation and sound. Since fourteenth-century singers could not

have anticipated our more strongly prescriptive notation, they were trained to

realise in performance what the notation in conjunction with their training

implied. Most things that our notation implies without any separate symbolic

representation can be subsumed under the heading of performance practice and

are to do with continuous quantities, for example, tempo (unnotated rubato in

Chopin, for example). It is therefore striking to us that in the fourteenth century

pitch a discrete musical element is dependent upon `performance practice' in

our sense. Unlike the elements that lack separate graphemes in our notation, the

performer of inflections caused by counterpoint is not at liberty to choose the

degree of his response. Thus, the placement of semitones for reasons of

counterpoint is not really a `performance practice' which implies an element of

conscious choice as to the degree to which the practice is followed. Instead it is a

notational convention. This is not to argue that every single interval decision is

absolutely prescribed, since some decisions will not be connected with the correct

approach to perfect consonance. The singer may then decide how to solmise a

note (especially the note b) based on other factors, such as his understanding of

line and phrase structure, which may be open to variance from one singer to

another.

13. For an exposition of the idea of counterpoint as analogous to grammar, see Bent,

`The Grammar of Early Music'.

14. `Sed ipsa frequenter sunt in B-fa B-mi virtualiter licet semper non signetur'.

Leofranc Holford-Steven's translation is taken from Bonnie J. Blackburn,

`Review of Thomas Brothers, Chromatic Beauty in the Late Medieval Chanson:

An Interpretation of Manuscript Accidentals', Journal of the American

Musicological Society, 51 (1999), pp. 63036.

15. Most recently in Brothers, Chromatic Beauty, where he states that there is `poor

support for it [counterpoint inflections] by writings from the period' (p. 22).

Brothers' designation of counterpoint inflections as an `unnotated convention'

reveals his twentieth-century perspective, since it is only in the light of our later,

more prescriptive approach to accidentals that fourteenth-century ones are

unnotated.

16. Bent, `The Grammar of Early Music', pp. 359.

17. Ibid., p. 36.

18. Over the course of the fourteenth century, the general trend was that the

conceptual length of the imperfect sonority was extended over more than one

Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 2000 Music Analysis, 19/iii (2000)

346 ELIZABETH EVA LEACH

tenor note leading to (fairly short-range) prolongation of the expectation of

resolution. This might well be the place at which `harmonic tonality' began,

rather than with the mirage of VI cadences (often rather more an archaic use of a

38 directed progression than anything progressive see for example the frequent

examples in Machaut's Nes com porroit (B33)) which attracted so much attention

from earlier musicologists; see Kevin N. Moll (ed.), Counterpoint and

Compositional Process in the Time of Dufay (New York: Garland, 1997), pp. 364.

19. The bar numbers are taken from Schrade's edition because it is more widely

available than the preferable edition of Ludwig. One of the more unequivocal

results of this study is to emphasise the importance of a consideration of the full

contexts of the original manuscript sources for medieval songs. Readers are thus

advised to consult microfilms and facsimiles if at all feasible, or, at least, to

consider the corrections to the modern editions detailed in Earp, Guillaume de

Machaut: A Guide to Research, Ch. 7.

20. I am using the term cadence to refer specifically to closural articulations.

Although `cadence' is a fourteenth-century term for what (following Sarah

Fuller) I have termed the directed progression, the latter term is used here to

avoid confusion. As Fuller shows, directed progressions are used to join phrases

and to open them as well as to close them; cadences (closing formulae) are not

always marked by directed progressions. See Sarah Fuller, `Tendencies and

Resolutions: The Directed Progression in Ars Nova Music', Journal of Music

Theory, 36/ii (1992), pp. 22957.

21. The balades that have a T-Ca ouvert sonority which resolves back to the opening

of the A section are Jaim miex (B7) and Donnez signeurs (B26) (cantus recta e

0

),

Se je me plaing (B15) (tenor recta b-mi), Dame comment quamez (B16), Je sui

aussi (B20), Honte paour (B25), and Pas de tor (B30) (tenor ficta f-mi) and Je puis

trop bien (B28) (tenor recta b-fa). In addition, Biaute qui (B4) (contratenor ficta

f-mi) and De fortune (B23) (triplum ficta c

0

-mi) have directed progressions

leading back to the beginning in other tenor-discant pairs.

22. Sonorities are listed from the lowest note upwards. Where the parts are

inverted from their normative relative positions (from the bottom up: T-Ct-

Ca-Tr) the sonority is shown in triangular brackets, < >, as here, where the

formula <a-c

0

> means that the tenor has c' and the cantus has the a below.

23. It is interesting to note that the T-Ct directed progression from the ouvert ending

back to opening, which has the potential for being a directed one (g-b resolving to

d5) if the contratenor sings b-fa in the ouvert, is overruled by the voice-crossing

directed progression avoidance strategy of the primary T-Ca pair. In three sources

(all arguably related GVg B) the contratenor b in the ouvert is marked with a mi

sign for clarification. That this is cautionary (because it is not present in all sources)

suggests, firstly, that the T-Ca pair has priority and, secondly, that concern for the

overall sonority (an issue when it is of a breve's duration) in the ouvert would

preclude a b-fa when the cantus does not have an e-fa. These observations depend

upon, but are additional to, those that may be gleaned from theoretical precepts.

24. The modern editions do not give an accurate impression. Ludwig has rationalised

Music Analysis, 19/iii (2000) Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 2000

GUILLAUME DE MACHAUT'S DE TOUTES FLOURS 347

the mi sign to apply to the c

0

at the end of bar 13 even though the sign is, in all its

sources, clearly in the d

0

space, immediately preceding the d

0

at the start of bar 14.

Although signing ficta in anticipation is common, a retrospectively-acting sign

would be a scribal oddity for all three sources. Schrade simply omits the sign.

Both Ludwig and Schrade preserve the tenor b-mi sign, thereby effectively

suppressing the directed progression in bars 1516.

25. Because bar 14 sets a rhyme word, all presentations of this sonority will have the

solmisation vowel `i' at this point. That the consonant `m' is also present in the

first line makes the pun even clearer. Within the structure of B5 the use of two

different approaches to a5 (the eventual ouvert sonority and secondary terminal

goal) is interesting and worthy of further analysis, for which there is no space

here. B5 shares the presence of two different approaches to the same resolution

with Dous amis (B6) and Samours ne fait (B1) in the latter of which the sonority in

question is also a5. In B1 (bars 910) the directed progression has the tenor b

marked mi in all sources. No source marks the cantus d

0

but I would argue that,

by analogy with B5, this instance is nevertheless clear enough. Using a

(questionable?) narrative of linear development, it might be possible to argue

on these grounds that B5 was written before B1. The hexachordal sign also in the

cantus part in its earliest source and a congratulatory textual pun in B5 (whereas

B1 has neither) may indicate the authorial over-caution of first time experiment.

26. Fuller, `Guillaume de Machaut: De toutes flours', p. 57.

27. The single surviving folio of W (Aberystwyth, National Library of Wales, 5010

C) which contains music but not B31 (f. 74v; most of the triplum of Quant en moy

(M1)) is also in a two-column format.

28. A further indication that this is not coterminous in definition or function with a

modern signature.

29. Brothers, Chromatic Beauty, p. 116.

30. There are several other cases where single Machaut sources state fa signs at the

beginning of lines immediately adjacent to notes that should be sung mi for

contrapuntal reasons: Dame comment quamez (B16), second cantus b, bar 27

directly follows a signature fa sign in C, but should be locally altered for the

caesural cadence; De triste / Quant / Certes (B29), cantus III b, bar 39 directly

follows a signature fa sign in the two-column source, G, a sign replicated in the

same position as a `floating signature' in the single column sources, Vg B and A,

but the b should be sung mi to effect the final cadence of the piece (Vg and Beven

mark the contratenor f with a mi sign); En amer (B41), contratenor b, bar 18,

follows a start-of-line fa sign in A, but should be sung mi to make a phrase-end