What Is Al Pacino's Next Big Move?

What Is Al Pacino's Next Big Move?

Uploaded by

Gerardo Palomino AybarCopyright:

Available Formats

What Is Al Pacino's Next Big Move?

What Is Al Pacino's Next Big Move?

Uploaded by

Gerardo Palomino AybarOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

What Is Al Pacino's Next Big Move?

What Is Al Pacino's Next Big Move?

Uploaded by

Gerardo Palomino AybarCopyright:

Available Formats

What is Al Pacinos Next Big Move?

For six years, the actor who made his mark as Michael Corleone has been obsessing over a new movie

about that ancient seductress Salome

Al Pacino likes to make trouble for himself. Everythings going along just fine and I go and f--- it up,

hes telling me. Were sitting on the front porch of his longtime Beverly Hills home in the low-key

section known as the flats. Nice house, not a mansion, but beautiful colonnades of towering palms

lining the street.

Youd think Pacino would be at peace by now, on this perfect cloudless California day. But dressed

head to toe in New York black, a stark contrast to the pale palette of the landscape, he speaks darkly

of his troubling dilemma: How is he going to present to the public his strange two-film version of the

wild Oscar Wilde play called Salome? Is he finally ready to risk releasing the newest versions of his six-

year-long passion project, as the Hollywood cynics tend to call such risky business? I do it all the

time, he says of the way he makes trouble for himself. Theres something about that discovery,

taking that chance. You have to endure the other side of the risk. The other side of the risk? They

said Dog Day [Afternoon+ was a risk, he recalls. When I did it, it was like What are you doing? You

just did The Godfather. Youre going to play this gay bank robber who wants to pay for a sex change?

This is so weird, Al. I said, I know. But its good. Most of the time the risk has turned out well, but

he still experiences the other side of the risk. The recent baffling controversy over his behavior

during the Broadway run of Glengarry Glen Ross, for instance, which he describes as like a Civil War

battlefield and things were going off, shrapnel... and I was going forward. Bullets over Broadway! It

suggests that, despite all hes achieved in four decades of stardom, Al Pacino (at 73) is still a little

crazy after all these years. Charmingly crazy; comically crazy, able to laugh at his own obsessiveness;

sometimes, crazy like a foxat least to those who dont share whatever mission hes on.

***

Actually, maybe troubled is a better word. He likes to play troubled characters on the edge of crazy,

or going over it. Brooding, troubled Michael Corleone; brooding troublemaker cop Frank Serpico; the

troubled gay bank robber in Dog Day Afternoon; a crazy, operatic tragicomic gangster hero, Tony

Montana, in Scarface, now a much-quoted figure in hip-hop culture. Hes done troubled genius Phil

Spector, hes done Dr. Kevorkian (I loved Jack Kevorkian, he says of Dr. Death, the pioneer of

assisted suicide. Loved him, he repeats). And one of his best roles, one with much contemporary

relevance, a troublemaking reporter dealing with a whistle-blower in The Insider. It has earned him

eight Academy Award nominations and one Oscar (Best Actor for the troubled blind colonel in Scent

of a Woman). Hes got accolades and honors galore. In person, he comes across more like the manic,

wired bank robber in Dog Day than the guy with the steely sinister gravitas of Michael Corleone.

Nevertheless, he likes to talk about that role and analyze why it became so culturally resonant.

Pacinos Michael Corleone embodies perhaps better than any other character the bitter unraveling of

the American dream in the postwar 20th centuryheroism and idealism succumbing to the corrupt

and murderous undercurrent of bad blood and bad money. Watching it again, the first two parts

anyway, it feels almost biblical: each scene virtually carved in stone, a celluloid Sistine Chapel painted

with a brush dipped in blood. And its worth remembering that Pacino almost lost the Michael

Corleone role because he troubled himself so much over the character. This morning in Beverly Hills,

he recounts the way he fought for a contrarian way of conceiving Michael, almost getting himself

fired. First of all, he didnt want to play Michael at all. The part for me was Sonny, he says, the

hotheaded older son of Marlon Brandos Godfather played by James Caan. That is the one I wanted

to play. But Francis *Ford Coppola, the director+ saw me as Michael. The studio didnt, everybody else

didnt want me in the movie at all. Francis saw me as Michael, and I thought How do I do this? I

really pondered over it. I lived on 91st and Broadway then and Id walk all the way to the Village and

back ruminating. And I remember thinking the only way I could do this is if, at the end of the day, you

dont really know who he is. Kind of enigmatic. It didnt go over well, the way he held back so much

at first, playing reticence, playing not-playing. If you recall, in that opening wedding scene he virtually

shrinks into his soldiers uniform. Everything to me was Michaels emergencein the transition, he

says, and its not something you see unfold right away. You discover that. That was one of the

reasons they were going to fire me, he recalls. I was unable to articulate that *the emergence+ to

Francis. Pacino admits his initial embodiment of Michael looked like an anemic shadow in the

dailies the producers were seeing. So they were looking at the *rushes+ every day in the screening

room and saying, Whats this kid doing? Who is this kid? Everybody thought I would be let go

including Brando, who was extremely kind to me. Pacino was mainly an off-Broadway New York

stage actor at that point, with only one major film role to his name, a junkie in The Panic in Needle

Park. He was risking what would be the role of a lifetime, one that put him alongside an acting

immortal like Brando, because he insisted that the role be a process, that it fit the method he used as

a stage actor. He studied with Lee Strasberg, guru of Method acting, and he is now co-president of the

Actors Studio. I always had this thing with film, he says. I had been in one, he says. And *as a

stage actor] I always had this sort of distance between myself and film. What kept me in the movie,

he recalls, was my good fortune that they had shot the scene where Michael shoots the cop *early

on, out of sequence]. And I believe that was enough for Francis to convince the powers that be that

they should keep me.

***

Pacinos process gets him in trouble to this day. Before I even bring up the subject, he mentions the

controversy surrounding the revival of David Mamets Glengarry Glen Ross. Hed played the role of

hotshot salesman Ricky Roma to much acclaim in the film, but when he took on a different part in a

new version of the playthe older, sadder, loserish salesman played by Jack Lemmon in the movie

there was trouble. The other actors were not used to Als extended process, wherein he needs

prolonged rehearsal time to find the character and often improvises dialogue. The rehearsal process

stretched into the sold-out Broadway previews, sometimes leaving the other actorswho were

following Mamets script faithfullylost. Which led to what are often euphemistically termed

creative differences. Thus the Civil War battlefield, Pacino says with a rueful shrug, the shrapnel

flying. The fact that he uses the term civil war is not an accident, I thinkit was an exposure of the

lifelong civil war within himself about when the process has to stop. Ideally for Pacino: never. And it

sounds like hes still got PTSD from the Glengarry Glen Ross civil war, cant stop talking about it. I

went through some real terrors, he says. He wanted to discover his character in the course of playing

him, wanted him to evolve, but Im a guy who really needs four months *to prepare a theater role+. I

had four weeks. So Im thinking Where am I? What is this? What am I doing here? And all of a sudden

one of the actors on stage turns to me and says, Shut the f--- up! Pacinos response: I wanted to

say, Lets keep that in. But I figured dont go there....And I kept saying, whatever happened to out-of-

town tryouts? The play reportedly made money but didnt please many critics. Pacino nonetheless

discovered something crucial with his process, something about himself and his father. Its the first

time in many, many years I learned something, he says. Sometimes I would just say what I was

feeling. I was trying to channel this character and...I felt as though he was a dancer. So sometimes Id

start dancing. But then I realizedguess what, I just realized this today! My father was a dancer and

he was a salesman. So I was channeling my old man. He talks about his father, whom he didnt know

well. His parents divorced when he was 2, and he grew up with his mother and grandmother in the

South Bronx. And he reminisces about the turning point in his life, when a traveling theater group

bravely booked what Pacino remembers as a huge movie theater in the Bronx for a production of

Chekhovs The Seagull, which he saw with some friends when he was 14. And I was sitting with about

ten other people, that was it, he recalls. But if you know the play, its about the crazy, troubled

intoxication of the theater world, the communal, almost mafia-family closeness of a theatrical troupe.

I was mesmerized, he recalls. I couldnt take my eyes off it. Who knows what I was hearing except

that it was affecting. And I went out and got all Chekhovs books, short stories, and I was going to

school in Manhattan [the High School of Performing Arts made famous by Fame] and I went to the

Howard Johnson there [in Times Square] at the time, to have a little lunch. And there serving me was

the lead in The Seagull! And I look at this guy, this kid, and I said to him, I saw you! I saw! you! In the

play! Hes practically jumping out of his porch chair at the memory. And I said, It was great, you

were great in it. It was such an exchange, Ill never forget it. And he was sort of nice to me and I said,

Im an actor! Aww, it was great. I live for that. Thats what I remember.

***

That pure thingthe communal idealism of actorsis at the root of the troublemaking. The radical

naked acting ethos of the Living Theatre was a big influence too, he says, almost as much as Lee

Strasberg and the Actors Studio and the downtown bohemian rebel ethos of the 60s.

In fact one of Pacinos main regrets is when he didnt make trouble. I read somewhere, I tell him,

that you considered Michael killing [his brother] Fredo at the end of Godfather II a mistake.

I do think that was a mistake, Pacino replies. I think *that made+ the whole idea of Part III, the idea

of [Michael] feeling the guilt of it and wanting forgivenessI dont think the audience saw Michael

that way or wanted him to be that way. And I didnt quite understand it myself.

Francis pulled *Godfather III] off, as he always pulls things off, but the original script was different. It

was changed primarily because Robert Duvall turned down the part of Tommy [Tom Hagen, the family

consigliere and Michaels stepbrother+. In the original script, Michael went to the Vatican because his

stepbrother, Robert Duvall/Tom Hagen was killed there, and he wanted to investigate that murder

and find the killers. That was his motivation. Different movie. But when Bob turned it down, Francis

went in that other direction.

***

What emerges from this is his own analysis of Michael Corleones appeal as a character, why he

connected so deeply with the audience. You didnt feel Michael really needed redemption or wanted

redemption? I asked. I dont think the audience wanted to see that, he says. He didnt ever think

of himself as a gangster. He was torn by something, so he was a person in conflict and had trouble

knowing who he was. It was an interesting approach and Francis took it very he paused. But I

dont think audiences wanted to see that. What the audiences wanted, Pacino thinks, is Michaels

strength: To see him become more like the Godfather, that person we all want, sometimes in this

harsh world, when we need somebody to help us. Channel surfing, he says, he recently watched the

first Godfather movie again and he was struck by the power of the opening scene, the one in which

the undertaker says to the Godfather, I believed in America. He believed, but as Pacino puts it,

Everybodys failed you, everythings failed you. Theres only one person who can help you and its

this guy behind the desk. And the world was hooked! The world was hooked! Hes that figure thats

going to help us all. Michael Corleones spiritual successor, Tony Soprano, is a terrific character, but

perhaps too much like us, too neurotic to offer what Michael Corleone promises. Though in real life,

Pacino and Tony Soprano have something in common. Pacino confides to me something Id never

read before: Ive been in therapy all my life. And it makes sense because Pacino gives you the

feeling hes on to his own game, more Tony Soprano than Michael Corleone. As we discuss The

Godfather, the mention of Brando gets Pacino excited. When you see him in A Streetcar Named

Desire, somehow hes bringing a stage performance to the screen. Something you can touch. Its so

exciting to watch! Ive never seen anything on film by an actor like Marlon Brando in Streetcar on film.

Its like he cuts through the screen! Its like he burns right through. And yet its got this poetry in it.

Madness! Madness! I recall a quote from Brando. He is supposed to have said, In stage acting you

have to show people what youre thinking. But in film acting [because of the close-up] you only have

to think it. Yeah, says Al. I think hes got a point there. Its more than that in factthe Brando

quote goes to the heart of what is Pacinos dilemma, the conflict hes desperately been trying to

reconcile in his Salome films. The clash between what film gives an actorthe intimacy of close-up,

which obviates the need for posturing and overemphatic gesturing needed to reach the balcony in

theaterand the electricity, the adrenaline, which Pacino has said, changes the chemicals in your

brain, of the live-wire act that is stage acting.

***

Indeed, Pacino likes to cite a line he heard from a member of the Flying Wallendas, the tight-rope-

walking trapeze act: Life is on the wire, everything else is just waiting. And he thinks hes found a

way to bring the wired energy of the stage to film and the film close-up to the stage. Film started

with the close-up, he says. You just put a close-up in thereD.W. Griffithboom! Done deal. Its

magic! Of course! You could see that inSalome today. Hes talking about the way he made an

electrifying film out of what is essentially a stage version of the play. (And then another film hes

called Wilde Salome about the making of Salome and the unmaking of Oscar Wilde.) Over the

previous couple of days, Id gone down to a Santa Monica screening room to watch both movies

(which hes been cutting and reshaping for years now). But he feelsafter six yearshes got it right,

at last. See what those close-ups fix on? Pacino asks. See that girl in the close-ups? That girl is

Jessica Chastain, whose incendiary performance climaxes in a close-up of her licking the blood

lasciviously from the severed head of John the Baptist. I had to admit that watching the film of the

play, it didnt play like a playno filming of the proscenium arch with the actors strutting and fretting

in the middle distance. The camera was onstage, weaving in and around, right up in the actors faces.

And heres Pacinos dream of acting, the mission hes on with Salome: My big thing is I want to put

theater on the screen, he says. And how do you do that? The close-up. By taking that sense of live

theater to the screen. The faces become the stage in a way? And yet youre still getting the

benefit of the language. Those people arent doing anything but acting. But to see them, talk with

them in your face.... Pacino has a reputation for working on self-financed film projects, obsessing

over them for years, screening them only for small circles of friends. Last time I saw him it was The

Local Stigmatic, a film based on a play by British avant-garde dramatist Heathcote Williams about two

lowlife London thugs (Pacino plays one) who beat up a B-level screen celebrity they meet in a bar just

because they hate celebrity. (Hmm. Some projection going on in that project?) Pacino has finally

released Stigmatic, along with the even more obscure Chinese Coffee, in a boxed DVD set.

***

But Salome is different, he says. To begin at the beginning would be to begin 20 years ago when he

first sawSalome onstage in London with the brilliant, eccentric Steven Berkoff playing King Herod in a

celebrated, slow-motion, white-faced, postmodernist production. Pacino recalls that at the time he

didnt even know it was written by Oscar Wilde and didnt know Wildes personal story or its tragic

end. I hadnt realized that the Irish-born playwright, author of The Picture of Dorian Gray and The

Importance of Being Earnest, raconteur, aphorist, showman and now gay icon, had died from an

infection that festered in prison where he was serving a term for gross indecency. Salome takes off

from the New Testament story about the stepdaughter of King Herod (played with a demented

lasciviousness by Pacino). In the film, Salome unsuccessfully tries to seduce the god-maddened John

the Baptist, King Herods prisoner, and then, enraged at his rebuff, she agrees to her stepfathers

lustful pleas to do the lurid dance of the seven veils for him in order to extract a hideous promise in

return: She wants the severed head of John the Baptist delivered to her on a silver platter. Its all

highly charged, hieratic, erotic and climaxes with Jessica Chastain, impossibly sensual, bestowing a

bloody kiss upon the severed head and licking her lips. Its not for the faint of heart, but Chastains

performance is unforgettable. Its like Pacino has been shielding the sensual equivalent of highly

radioactive plutonium for the six years since the performance was filmed, almost afraid to unleash it

on the world. After I saw it, I asked Pacino, Where did you find Jessica Chastain? He smiles. I had

heard about her from Marthe Keller [an ex-girlfriend and co-star in Bobby Deerfield]. She told me,

Theres this girl at Juilliard. And she just walked in and started reading. And I turned to Robert Fox,

this great English producer, and I said, Robert, are you seeing what Im seeing? Shes a prodigy! I was

looking at Marlon Brando! This girl, I never saw anything like it. So I just said, OK honey, youre my

Salome, thats it. People who saw her in thisTerry Malick saw her in [a screening of] Salome, cast

her in Tree of Lifethey all just said, come with me, come with me. She became the most sought-

after actress. [Chastain has since been nominated for Academy Awards in The Help and Zero Dark

Thirty.+ When she circles John the Baptist, she just circles him and circles him... He drifts off into a

reverie. Meanwhile, Pacino has been doing a lot of circling himself. Thats what the second film, Wilde

Salome, the Looking for Oscar Wilde-type docudrama, does: circle around the play and the

playwright. Pacino manages to tell the story with a peripatetic tour of Wilde shrines and testimonies

from witnesses such as Tom Stoppard, Gore Vidal and that modern Irish bard Bono. And it turns out

that it is Bono who best articulates, with offhand sagacity, the counterpoint relationship

between Salome and Wildes tragedy. Salome, Bono says on camera, is about the destructive power

of sexuality. He speculates that in choosing that particular biblical tale Wilde was trying to write

about, and write away, the self-destructive power of his own sexuality, officially illicit at the time.

Pacino has an electrifying way of summing it all up: Its about the third rail of passion. Theres no

doubt Pacinos dual Salome films will provoke debate. In fact, they did immediately after the lights

came up in the Santa Monica screening room, where I was watching with Pacinos longtime producer

Barry Navidi and an Italian actress friend of his. What do you call what Salome was experiencinglove

or lust or passion or some powerful cocktail of all three? How do you define the difference among

those terms? What name to give her ferocious attraction, her rage-filled revenge? We didnt resolve

anything but it certainly homes in on what men and women have been heatedly arguing about for

centuries, what were still arguing about in America in the age of Fifty Shades of Grey. Later in Beverly

Hills, I told Pacino about the debate: She said love, he said lust, and I didnt know. The passion is

the eroticism of it and thats whats driving the love, he says. Thats what I think Bono meant.

Pacino quotes a line from the play: Love only should one consider. Thats what Salome says. So

you feel that she felt love not lust? He avoids the binary choice. She had this kind of feeling when

she saw him. Somethings happening to me. And shes just a teenager, a virgin. Somethings

happening to me, Im feeling things for the first time, because shes living this life of decadence, in

Herods court. And suddenly she sees *the Baptists+ kind of raw spirit. And everything is happening to

her and she starts to say I love you and he says nasty things to her. And she says I hate you! I hate

you! I hate you! Its your mouth that I desire. Kiss me on the mouth. Its a form of temporary insanity

shes going through. Its that passion: You fill my veins with fire. Finally, Pacino declares, Of course

its love. It wont end the debate, but what better subject to debate about? Pacino is still troubling

himself over which film to release firstSalome or Wilde Salome. Or should it be both at the same

time? But I had the feeling that he thinks they are finally done, finally ready. After keeping at it and

keeping at itcutting them and recutting themthe time has come, the zeitgeist is right. (After I left,

his publicist Pat Kingsley told me that they were aiming for an October opening for both films, at last.)

Keeping at it: I think that may be the subtext of the great Frank Sinatra story he told me toward the

end of our conversations. Pacino didnt really know Sinatra and you might think there could have

been some tension considering the depiction of the Sinatra character in Godfather. But after some

misunderstandings they had dinner and Sinatra invited him to a concert at Carnegie Hall where he

was performing. The drummer Buddy Rich was his opening act. Buddy Rich? you might ask, the fringe

Vegas rat-pack guy? Thats about all Pacino knew about him. I thought oh, Buddy Rich the drummer.

Well thats interesting. Were gonna have to get through this and then well see Sinatra. Well, Buddy

Rich starts drumming and pretty soon you think, is there more than one drum set up there? Is there

also a piano and a violin and a cello? Hes sitting at this drum and its all coming out of his drumsticks.

And pretty soon youre mesmerized. And he keeps going and its like hes got 60 sticks there and all

this noise, all these sounds. And then he just starts reducing them, and reducing them, and pretty

soon hes just hitting the cowbell with two sticks. Then you see him hitting these wooden things and

then suddenly hes hitting his two wooden sticks together and then pretty soon he takes the sticks up

and were all like this *miming being on the edge of his seat, leaning forward+. And he just separates

the sticks. And only silence is playing. The entire audience is up, stood up, including me, screaming!

Screaming! Screaming! Its as if he had us hypnotized and it was over and he leaves and the audience

is stunned, were just sitting there and were exhausted and Sinatra comes out and he looks at us and

he says. Buddy Rich, he says. Interesting, huhWhen you stay at a thing. You related to that?

"I'm still looking for those sticks to separate. Silence. You know it was profound when he said that.

'It's something when you stay at a thing."'

A Scientific Laboratory 170 Feet High in the Sky

Grand-scale ecology brings a Virginia forest under unprecedented scrutiny by Smithsonian researchers

Deep in the heart of Posey Hollow, on the grounds of the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute

in Front Royal, Virginiapast the straight, sturdy hickories and a gnarled, 250-year-old black gum, the

oldest tree in a forest that was clear-cut for farming in Colonial timesa galvanized steel tower rises

170 feet into the sky. When construction was completed, in late July, it became the tallest structure

for at least an hours drive in any direction. When scientists install an array of instruments on the

tower next month, the surrounding forest will become one of the most closely studied in the world.

The tower is one of 60 to be built across the United States as part of the National Ecological

Observatory Network (NEON), a massive monitoring project, sponsored by the National Science

Foundation, that will take the pulse of the nations environment. For 30 years starting in 2017, when

the network is due to be completed, the towers will continuously measure temperature, carbon-

dioxide concentration, moisture and many other variables in 20 different types of ecosystems. Posey

Hollow is representative of a second-growth Eastern forest, there being virtually no old-growth forest

left in the Eastern United States. Another tower will be installed at a Smithsonian research center on

the shore of the Chesapeake Bay, to capture a Mid-Atlantic coastal ecosystem. At each NEON site

researchers also will monitor soil conditions and collect insects, birds, plants and small animals. Once

a year or so, airplanes carrying laser equipment will fly over the forests to create high-resolution

digital scans of the tree canopy so scientists can track its density and growth. The NEON project will

also incorporate data from 46 aquatic sites to paint a more complete picture of our ecosystem

nationwide. Ecology is going big-scale. If you want to understand how the environment works, you

need to sample widely and bring in as many variables as possible, says Bill McShea, a Smithsonian

wildlife ecologist. But so far, nobody has tried anything nearly as comprehensive as this. The

Conservation Biology Institute was founded to conduct research on endangered animals, and it is still

home to such creatures as cheetahs, red pandas and gazelles. But over the past five years researchers

have taken a magnifying glass to a 63-acre section of Posey Hollow to better understand a forest that

is growing without the pressures of encroaching development. Every tree in here with a diameter of

over a centimeter weve mapped, measured and identified, McShea told me in early June as we

hiked into the forest to see where the tower would be built. That comes to 41,031 trees of 65 species.

The scientists say the data gathered by the tower instruments will shed new light on the critical role

that forests play in the greater environment. What Im most excited about is a sensor that makes

continuous measurement of the exchange of carbon dioxide and water vapor between the forest and

the atmosphere, says Kristina Teixeira, a forest ecologist at the institute. From this, you can get the

total amount of carbon dioxide being taken up by the forest on a daily or annual time scale. By

comparing the rate of carbon dioxide absorption with surveyed tree growth, scientists will be able to

calculate how effectively forests like this one mitigate greenhouse-gas emissionsan increasingly

important issue as the climate changes. Other data will help researchers model how forests are

affected by drought, rising temperatures and other factors, and could help them determine how

certain native trees, such as that ancient black gum, withstand invasive species. One of the most

innovative aspects of NEON, though, has less to do with gathering information than with distributing

it: The data will be made publicly available in real time over the Internet, so everyone with a stake in

the ongoing changes to our environment will have a chance to monitor them. As Teixeira says,

Anyone with a good idea can just go in there and test their hypothesis.

You might also like

- D20 Modern - Solid The D20 Blaxploitation ExperienceDocument66 pagesD20 Modern - Solid The D20 Blaxploitation ExperienceBob Johnson100% (5)

- A Galaxy Not So Far Away: Writers and Artists on Twenty-five Years of Star WarsFrom EverandA Galaxy Not So Far Away: Writers and Artists on Twenty-five Years of Star WarsRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (12)

- Disadvantages of Genetically Modified CropsDocument6 pagesDisadvantages of Genetically Modified CropsPrathamGupta100% (1)

- A Higher Calling Phillip Seymor HoffmanaDocument14 pagesA Higher Calling Phillip Seymor Hoffmanaalchymia_ilNo ratings yet

- The Complete History of The Return of the Living DeadFrom EverandThe Complete History of The Return of the Living DeadRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- Nicolas Cage On Acting, Philosophy and Searching For The Holy Grail - The New York TimesDocument13 pagesNicolas Cage On Acting, Philosophy and Searching For The Holy Grail - The New York Timesemanala2015No ratings yet

- William ShatnerDocument1 pageWilliam ShatnerJames JacksonNo ratings yet

- The Best FilmsDocument11 pagesThe Best Filmsapi-353792315No ratings yet

- Bryan Cranston, Eddie Redmayne and 18 Others Share Secrets For Getting Lost in Character - Hollywood ReporterDocument26 pagesBryan Cranston, Eddie Redmayne and 18 Others Share Secrets For Getting Lost in Character - Hollywood ReporterMārs LaranNo ratings yet

- My Life in the Frank-N-Furter Cult: The Hangover Hour Report, #3From EverandMy Life in the Frank-N-Furter Cult: The Hangover Hour Report, #3No ratings yet

- Rocky Horror HorrorDocument11 pagesRocky Horror HorrorPhantomimic100% (9)

- Corman/Poe: Interviews and Essays Exploring the Making of Roger Corman’s Edgar Allan Poe films, 1960–1964From EverandCorman/Poe: Interviews and Essays Exploring the Making of Roger Corman’s Edgar Allan Poe films, 1960–1964No ratings yet

- Book List 2019Document50 pagesBook List 2019Henry BeglerNo ratings yet

- On "Succession," Jeremy Strong Doesn't Get The Joke The New YorkerDocument30 pagesOn "Succession," Jeremy Strong Doesn't Get The Joke The New YorkerAnelise AlvarezNo ratings yet

- With Love, Mommie Dearest: The Making of an Unintentional Camp ClassicFrom EverandWith Love, Mommie Dearest: The Making of an Unintentional Camp ClassicNo ratings yet

- Spike, Mike, Slackers & Dykes: A Guided Tour Across a Decade of American Independent CinemaFrom EverandSpike, Mike, Slackers & Dykes: A Guided Tour Across a Decade of American Independent CinemaNo ratings yet

- John Milius PDFDocument16 pagesJohn Milius PDFkdefreitas704No ratings yet

- Sean Baker On LA Moviegoing and His Cannes-Winning AnoraDocument5 pagesSean Baker On LA Moviegoing and His Cannes-Winning AnoraBogdan Theodor OlteanuNo ratings yet

- Halloween TranscriptDocument9 pagesHalloween Transcriptapi-312453884No ratings yet

- I Found it at the Movies: Film Noir Reviews: Movie Review Series, #1From EverandI Found it at the Movies: Film Noir Reviews: Movie Review Series, #1No ratings yet

- Showgirls, Teen Wolves, and Astro Zombies: A Film Critic's Year-Long Quest to Find the Worst Movie Ever MadeFrom EverandShowgirls, Teen Wolves, and Astro Zombies: A Film Critic's Year-Long Quest to Find the Worst Movie Ever MadeRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (25)

- Excerpt From "The Friedkin Connection: A Memoir" by William Friedkin. Copyright 2013 by William Friedkin. Reprinted Here by Permission of Harper. All Rights Reserved.Document5 pagesExcerpt From "The Friedkin Connection: A Memoir" by William Friedkin. Copyright 2013 by William Friedkin. Reprinted Here by Permission of Harper. All Rights Reserved.wamu8850No ratings yet

- The Black Belle Press NotesDocument26 pagesThe Black Belle Press Notesapi-76822481No ratings yet

- Round Up The Usual Archetypes!Document3 pagesRound Up The Usual Archetypes!Jac ListerNo ratings yet

- Gutter Auteur The Films of Andy Milligan by Rob CraigForeword by Robert PatrickDocument536 pagesGutter Auteur The Films of Andy Milligan by Rob CraigForeword by Robert PatrickArch HallNo ratings yet

- Carroll O'Connor InterviewDocument1 pageCarroll O'Connor InterviewFrank LoveceNo ratings yet

- Howl PDFDocument4 pagesHowl PDF1474543100% (1)

- Neptune Noir: Unauthorized Investigations into Veronica MarsFrom EverandNeptune Noir: Unauthorized Investigations into Veronica MarsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (56)

- Sex, Cinema & Showgirls by Paul VerhoevenDocument12 pagesSex, Cinema & Showgirls by Paul VerhoevenB.DanielNo ratings yet

- Time After Time Movie ReviewDocument2 pagesTime After Time Movie ReviewOshram KinoNo ratings yet

- Marlon & Greg: My Life and Filmmaking Adventures with Hollywood’s Polar OppositesFrom EverandMarlon & Greg: My Life and Filmmaking Adventures with Hollywood’s Polar OppositesNo ratings yet

- CarnageDocument7 pagesCarnageKiran PashaNo ratings yet

- Desperately Seeking EthanDocument7 pagesDesperately Seeking Ethaneliteles1No ratings yet

- Quentin Tarantino and The Poetry Between The Lines: IntroDocument46 pagesQuentin Tarantino and The Poetry Between The Lines: IntroSergio AntibioticeNo ratings yet

- Environment and EcologyDocument13 pagesEnvironment and EcologyVarunVjLellapalliNo ratings yet

- EGE 312 NotesDocument20 pagesEGE 312 NotesJeric RuNo ratings yet

- Danna Sofia Valero Reina-Actividad 1 InglesDocument5 pagesDanna Sofia Valero Reina-Actividad 1 InglesLina ValeroNo ratings yet

- External AnalysisDocument8 pagesExternal AnalysisYasmine MancyNo ratings yet

- Tropical RainforestsDocument9 pagesTropical RainforestsSamana FatimaNo ratings yet

- National Environmental Policy and StrategiesDocument18 pagesNational Environmental Policy and StrategiesAyushi ChandraNo ratings yet

- Fragile Environments IGCSE RevisionDocument18 pagesFragile Environments IGCSE Revisionapi-232441790No ratings yet

- Speech On NatureDocument2 pagesSpeech On Naturesr.sowmiya thereseNo ratings yet

- Gurdaspur-I: Integrated Watershed Mangement Programme (Iwmp)Document126 pagesGurdaspur-I: Integrated Watershed Mangement Programme (Iwmp)Gurry DhillonNo ratings yet

- 01 GoldammerDocument66 pages01 GoldammerGuilherme Moura FagundesNo ratings yet

- Margomulyo MangDocument2 pagesMargomulyo Mangdaffa fadhilNo ratings yet

- Multidisciplinary Nature of Environment StudiesDocument8 pagesMultidisciplinary Nature of Environment StudiesjoshivishwanathNo ratings yet

- Aakash Revised SyllabusDocument8 pagesAakash Revised SyllabusRita Nayak100% (2)

- Eastern Thailand - Jon Jandai - Farmer, Builder and Man of LeisureDocument3 pagesEastern Thailand - Jon Jandai - Farmer, Builder and Man of Leisuregl101No ratings yet

- 2009 Galster - What Is NeighbourhoodDocument21 pages2009 Galster - What Is NeighbourhoodVeronica TapiaNo ratings yet

- Eagles Island Final Document - Compressed - 2021.10.01Document71 pagesEagles Island Final Document - Compressed - 2021.10.01preston lennonNo ratings yet

- Water Management System in PakistanDocument6 pagesWater Management System in PakistanWajiha Asad KiyaniNo ratings yet

- Ecological Systems Theory in Social WorkDocument27 pagesEcological Systems Theory in Social WorkEndija RezgaleNo ratings yet

- Status, Trends, and Advances in Earthworm Research and VermitechnologyDocument136 pagesStatus, Trends, and Advances in Earthworm Research and Vermitechnologyxafemo100% (1)

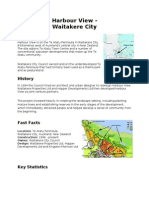

- Harbourview (Nauman)Document3 pagesHarbourview (Nauman)Nauman AhmadNo ratings yet

- By Sanjana Ramachandran Anusha B Kandikere Shraddha Vidhi M Jain Bhoomika R Viii C'Document27 pagesBy Sanjana Ramachandran Anusha B Kandikere Shraddha Vidhi M Jain Bhoomika R Viii C'sanjanaNo ratings yet

- Bishoftu Forem2Document29 pagesBishoftu Forem2Aida Mohammed100% (1)

- Oops! Something Went Wrong On Our EndDocument25 pagesOops! Something Went Wrong On Our EndHarvagale BlakeNo ratings yet

- Posions On Your PlateDocument40 pagesPosions On Your PlateRagunathan K ChakravarthyNo ratings yet

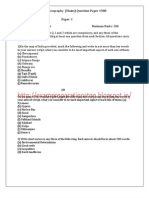

- Geography: (Mains) Question Paper 1988 Paper - IDocument3 pagesGeography: (Mains) Question Paper 1988 Paper - INakka JaswanthNo ratings yet

- Tercera Actividad de InglesDocument5 pagesTercera Actividad de InglesKarla ParraNo ratings yet

- Oil Spill Introduction 2019 LRDocument36 pagesOil Spill Introduction 2019 LRBrian TuckerNo ratings yet

- National Rangeland Policy 2010 - DraftDocument16 pagesNational Rangeland Policy 2010 - DraftFarhat Abbas DurraniNo ratings yet

- Bell The Ideology of Environmental DominationDocument20 pagesBell The Ideology of Environmental DominationngtomNo ratings yet