0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

101 viewsNordic Outlook 1408: Continued Recovery - Greater Downside Risks

Nordic Outlook 1408: Continued Recovery - Greater Downside Risks

Uploaded by

SEB GroupAccelerating global growth is the most probable world economic scenario in 2015, helped by an improved outlook in such key countries as the United States, the United Kingdom, China and India, write SEB's Economist in the latest issue of Nordic Outlook.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Nordic Outlook 1408: Continued Recovery - Greater Downside Risks

Nordic Outlook 1408: Continued Recovery - Greater Downside Risks

Uploaded by

SEB Group0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

101 views53 pagesAccelerating global growth is the most probable world economic scenario in 2015, helped by an improved outlook in such key countries as the United States, the United Kingdom, China and India, write SEB's Economist in the latest issue of Nordic Outlook.

Original Title

Nordic Outlook 1408: Continued recovery – greater downside risks

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Accelerating global growth is the most probable world economic scenario in 2015, helped by an improved outlook in such key countries as the United States, the United Kingdom, China and India, write SEB's Economist in the latest issue of Nordic Outlook.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

101 views53 pagesNordic Outlook 1408: Continued Recovery - Greater Downside Risks

Nordic Outlook 1408: Continued Recovery - Greater Downside Risks

Uploaded by

SEB GroupAccelerating global growth is the most probable world economic scenario in 2015, helped by an improved outlook in such key countries as the United States, the United Kingdom, China and India, write SEB's Economist in the latest issue of Nordic Outlook.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 53

Continued global recovery,

but greater downside risks

Riksbank will cut key rate in

uncharted political landscape

Nordic Outlook

Economic Research August 2014

Contents

Nordic Outlook August 2014 | 3

International overview 5

Theme: What should central banks aim for? 14

The United States 16

Theme: Is low potential growth in the US here to stay? 20

Japan 21

Asia 22

The euro zone 25

Theme: Public debt problems persist in the euro zone 29

The United Kingdom 30

Eastern Europe 31

The Baltics 33

Sweden 34

Theme: New political landscape after the election 39

Denmark 41

Norway 43

Finland 46

Economic data 48

Boxes

International overview: Permanently higher risk level 7

International overview: Fiscal policy makers seek new mechanisms 10

International overview: How long will the recovery last? 12

USA: Temporary factors have lowered 2014 GDP 16

USA: Fewer households are moving 17

USA: Neutral interest rate is lower today 19

The euro zone: ECB rotation, minutes, fewer meetings 28

Sweden: Low pay hikes a threat to ination target? 36

Denmark: Is Denmark overheating? 42

4 | Nordic Outlook August 2014

Economic Research

This report was published on August 26, 2014.

Cut-o date for calculations and forecasts was August 21, 2014.

Robert Bergqvist

Chief Economist

+ 46 8 506 230 16

Elisabet Kopelman

Head of Economic Research

Japan

+ 46 8 506 230 17

Hkan Frisn

Head of Economic Forecasting

Sweden

+ 46 8 763 80 67

Daniel Bergvall

Economist

The euro zone & Finland

+46 8 763 85 94

Mattias Brur

Economist

US & United Kingdom

+ 46 8 763 85 06

Ann Enshagen Lavebrink

Editorial Assistant

+ 46 8 763 80 77

Mikael Johansson

Economist

The Baltics, Poland & Eastern Europe

+ 46 8 763 80 93

Andreas Johnson

Economist

China, India, Ukraine & Russia

+46 8 763 80 32

Frederik Engholm-Hansen

SEB Copenhagen

Denmark

+45 3328 1469

Thomas Thygesen

SEB Copenhagen

Denmark

+45 3328 1008

Olle Holmgren

Trading Strategy Stockholm

Sweden

+46 8 763 80 79

Erica Blomgren

SEB Oslo

Norway

+47 2282 7277

Stein Bruun

SEB Oslo

Norway

+47 2100 8534

SEB Economic Research, K-A3, SE-106 40 Stockholm

International overview

Nordic Outlook August 2014 5

Continued recovery, but downside risks have increased

Central bank support and spare resources

will help fuel continued economic recovery

US growth over 3 per cent in 2015 and 2016

Rising EM growth, despite structural flaws

Euro zone: Intensified deflation risks

ECB launching QE in March, Fed hike in April

Slow yield upturn, wider US-German spread

Gradual US dollar appreciation against euro

The world economy continues to be marked by a fragile

recovery of varying strength. In the United States, the trend

became clearer after a slump early in 2014. GDP growth

rebounded sharply in the second quarter and the labour

market is showing gradual improvement. The British economy

has also shown strength. In China, first half growth was higher

than expected despite a real estate market downturn. In

Japan, however, hopes of a clear export upturn have been

dashed. Negative signals are even more predominant in the

euro zone, where GDP stagnated completely in the second

quarter. This weakness also applies to Germany, where

industrial production and optimism have fallen. To a minor

extent, the trade conflict with Russia has probably played a

role, at least psychologically.

We foresee a continued tug-of-war between different forces.

Monetary policy will remain very expansionary. We expect

further stimulus programmes from various central banks,

especially the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of

Japan (BoJ), but also from Swedens Riksbank. The US and UK

central banks will begin normalising key interest rates in the

spring of 2015 but will probably carry out their rate hikes very

cautiously. In general, there is lingering fundamental

uncertainty about the effectiveness of monetary policy, in

an environment where balance sheets remain in great need of

repair. Fiscal policy is now moving into a rather neutral

phase after earlier budget-tightening. Due to high public

debt, there is very limited room for stimulus. Instead, the

focus is on measures that do not weigh down budgets so

much. This applies, for example, to tax reforms that benefit

lower-income households and opportunities to bring about

capital spending by using various methods to initiate

partnerships between public institutions and the business

sector. Geopolitical uncertainty will probably continue

during the foreseeable future, as various regional conflicts

unfold. This is apparently not having a big impact on oil prices,

but trade disruptions and more cautious investment behaviour

are likely to dampen future growth to some extent.

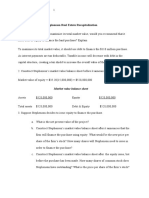

Global GDP growth

Year-on-year percentage change

2013 2014 2015 2016

United States 2.2 2.2 3.4 3.1

Japan 1.5 1.1 1.2 0.8

Germany 0.1 1.2 1.4 1.8

China 7.7 7.5 7.3 6.9

United Kingdom 1.7 3.1 2.8 2.6

Euro zone -0.4 0.7 1.1 1.5

Nordic countries 0.6 1.5 2.0 2.2

Baltic countries 2.9 2.1 2.7 3.6

OECD 1.4 1.9 2.5 2.4

Emerging markets 4.8 4.6 5.0 5.1

World, PPP* 3.3 3.4 3.9 4.0

Source: OECD, SEB * Purchasing power parities

We arrive at the conclusion that accelerating growth in 2015

is the most probable world economic scenario. In an

environment of low resource utilisation, there is ample room

for continued powerful monetary stimulus. Historically

speaking, it has been very unusual for an economic downturn

to occur before the central bank normalisation process has

even begun. Heightened geopolitical uncertainty and

continued sluggishness due to balance sheet adjustments will

diminish the power of the upturn and delay a clear capital

spending upturn. But given a rising US economy, it is unlikely

that this will end the global recovery. Overall, we expect GDP

growth in the 34 mainly affluent countries of the

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development

(OECD) to be 2.5 per cent in 2015 and a tenth of a

percentage point lower in 2016. We have thus revised both

our 2014 and 2015 OECD forecasts downward by two tenths.

In emerging market (EM) economies, we also expect

growth to speed up somewhat in 2015 and 2016. Most such

countries have shown resilience amid the prevailing

geopolitical turbulence. We also believe they are generally well

equipped to deal with the impact of the US Federal Reserves

cautious rate hikes. Overall, EM growth will climb from 4.6 per

cent in 2014 to some 5 per cent in 2015 and 2016.

In an environment where major central banks are moving in

different directions and growth is accelerating somewhat, but

where large downside risks persist, financial market trends will

be less clear. Looking ahead, US and UK central bank rate hikes

are likely to lead to a moderate upturn in bond yields. Due

International overview

6 Nordic Outlook August 2014

to ever-widening interest rate gaps between the Fed and the

ECB, the spread between US and German 10-year sovereign

yields will increase further from todays already high level.

Bond yields will thus remain historically low in Europe; the

German 10-year yield will not exceed 2 per cent during our

forecast period. Stock market volatility will probably

increase as the Feds rate hikes approach. If our forecast of

continued low interest rates and a degree of acceleration in

global growth proves correct, there is potential for rising share

prices further ahead. Exchange rates will also be largely

influenced by differences in monetary policy. Among other

things, this implies a gradual appreciation of the US dollar. We

expect the EUR/USD rate to continue down to 1.20 by the end

of 2016. Scandinavian currencies will eventually appreciate

against the euro, but cautious central banks will help limit that

potential. This autumn the Swedish krona will also be weighed

down by further Riksbank stimulus measures and by political

uncertainty related to the September parliamentary election.

US: Growth engine of unruly world economy

Most indications are now that the US economic slump early in

2014 was due to temporary factors such as severe winter

weather, de-stocking in the automotive industry and the

temporary effects of economic policy measures (see the box in

the US section of this issue). GDP growth rebounded to an

annualised 4.0 per cent in the second quarter. More and more

factors suggest a continued upturn, with GDP growth above 3

per cent in both 2015 and 2016. Confidence indicators are at

high levels and the labour market has shifted to higher gear.

Rising wealth and good incomes will benefit consumption. At

present, fiscal policy is less strict and less uncertain than for a

long time. Even if the Fed begins hiking its key interest rate

next spring, monetary policy will provide continued support. In

such an environment, we see good prospects for cyclical

sectors to expand from todays depressed levels. By the end of

our forecast period, unemployment will fall below its

equilibrium level, but we do not expect general resource

problems to stop the recovery.

Renewed euro zone weakness

In the euro zone, disappointments have predominated in

recent months. Even the German economy has weakened,

which is partly connected to the direct and indirect

consequences of trade disruption with Russia. The euro zone

economy is generally vulnerable, in a situation where balance

sheet adjustment has a long way to go. In addition, the credit

market is not yet working satisfactorily, though risk premiums

for government securities have greatly decreased. Because of

weak real growth, combined with very low inflation, nominal

GDP is stagnating. This worsens the debt dynamic in many

countries, since the budget-tightening they have implemented

has not been enough to bring down their debt as a percentage

of GDP. We have revised our 2014 and 2015 growth

forecasts rather clearly downward to 0.7 and 1.1 per cent,

respectively (previously 1.0 and 1.6). In 2016, growth will be 1.5

per cent.

This somewhat stronger growth will be largely driven by ECB

stimulus programmes. The measures the bank approved in

early June have not yet begun to have much effect, and also we

expect further stimulus programmes ahead. Other countries

will also provide some help. Several crisis-hit countries,

especially Spain, are entering a more robust growth phase after

their previous deep downturns. France and Italy are showing

worrisome stagnation tendencies, however. The process of

increasing European Union political and economic integration

is moving sluggishly. The election to the European Parliament

last spring was a success for parties that oppose expanded

supranational powers. In the near term, the process of creating

a common EU banking union will continue, but otherwise not

much is likely to happen. The euro zone thus has quite far to go

before it has laid the groundwork for a stable, well-functioning

currency union. The ECBs efforts remain vital in order to keep

the euro zone together.

EM economies are showing resilience

In recent months, emerging market (EM) economies have

shown resilience to increased geopolitical uncertainty. Overall,

we anticipate some acceleration in growth this coming year,

among other things because there is room for continued loose

monetary policies. Although EM countries are struggling with

various types of structural problems, we still believe they are

rather well equipped to meet the challenges that the Feds

coming interest rate hikes will bring. In particular, generally

strong external balances and robust exchange rate systems are

International overview

Nordic Outlook August 2014 7

in contrast to the situation in the late 1990s when the Asian

financial crisis broke out.

The Chinese economy seems to be holding up well against

the ongoing downturn in the construction sector. We have

revised our GDP growth forecast a bit upward to 7.5 per cent.

After that we foresee a controlled and cautious slowdown to

6.9 per cent in 2016. There are high hopes for the economic

policies of the new Indian government (BJP). We foresee a

certain risk of disappointments on the reform front but still

believe that growth will accelerate from 5.0 per cent this year

to around 6 per cent in 2015 and 2016. Structural factors have

contributed to the sharp deceleration in Brazilian growth over

the past few years. During 2000-2010, annual growth averaged

3.7 per cent. Our GDP forecast for 2014 is 1 per cent. Far-

reaching structural reforms are needed to get the economy

moving. Capital spending will need to take over from private

consumption as the main driver of growth. The presidential

election in October could serve as a catalyst for change, but

none of the main candidates has shown an impressive reform

agenda. Weak growth will continue during our forecast period,

with GDP rising by 2-2.5 per cent in 2015 and 2016.

Downside risks have increased somewhat

Because of greater geopolitical risks, for example connected to

risks of escalation in the Russia-Ukraine crisis combined with

renewed stagnation tendencies mainly in the euro zone,

downside risks have increased somewhat in recent months.

Looking ahead a bit, we also see a certain risk that US interest

rate hikes may come at such an early stage that they will have

negative international consequences. We have thus raised

the probability of our low-growth scenario to 30 per cent

from 25 per cent in the May 2014 issue of Nordic Outlook.

As in recent issues of Nordic Outlook, we estimate the

probability of a faster-growth scenario at 20 per cent. Our

main scenario implies that secondary effects from the

American economic upturn will be weaker than usual. Yet one

potential upside for our global forecast is that the positive

international impact of the US upturn will be more in line with

historical patterns.

Permanently higher geopolitical risk level

In recent months, geopolitical uncertainty has escalated.

The main focus has been on Russia-Ukraine, the Islamic

State (IS) offensive in Iraq and the Israel-Palestine conflict.

Apart from these, there are a number of other conflicts in

which no solution is in sight, for example the civil war in

Syria, the ongoing disintegration of Libya and increased

tensions between various groups in other African countries.

Behind the scenes, we are also seeing how Chinas increas-

ing strength and growing long-term power ambitions are

creating tensions in East Asia, especially in relations to

Japan and Vietnam.

The EU has entered the toughest phase (No. 3) of its sanc-

tions plan against the Russian economy. Russia has re-

sponded with trade barriers in the aviation, agriculture and

food sectors. Western sanctions are intensifying the struc-

turally weak trend in the Russian economy, and the conflict

has in itself already pushed Ukraine into a deep recession.

Yet in our assessment, the direct effects on the EU will

be rather small. Hardest hit will be Finland and the Baltic

countries, which are the most dependent on trade with

Russia. Looking ahead, we believe that the EU countries will

not be inclined to escalate trade sanctions further, partly

due to their vulnerable domestic economic situation. How-

ever, the likelihood of a Russian invasion in parts of eastern

Ukraine has recently increased, and thus also the risks of

serious secondary economic effects.

Oil prices have not been driven up by the trouble spots

in the Middle East and North Africa. Instead they have

tended to fall. Perhaps the most important link between

geopolitical turmoil and global economic activity seems to

have been broken, making the impact of such turmoil more

unclear. Greater geopolitical tensions presumably have a

negative psychological effect, primarily on the investment

climate. But sometimes the massive new flow from crisis

flashpoints seems to lead to an initial tendency to exagger-

ate the global economic and financial effects of emerging

crises.

In a long-term perspective, however, we can still foresee the

beginnings of a negative trend. The relaxation of tensions

following the fall of the Soviet Union and the end of the

Cold War stimulated the world economy. The shift to-

wards greater democracy and economic liberalisation

helped drive demand and trade for a long time. The US was

able to transfer resources from military to civilian use, but

still maintain its role as an unchallenged superpower that

guaranteed stable international trade conditions.

There are many indications that we are now entering a

phase of weakened US authority, for both political and

economic reasons. The conflict of interests between the

West and Russia is likely to persist, especially in light of the

prevailing political trends in Russia. Meanwhile the rivalry

between China and the US is likely to grow as Southeast

Asia becomes an increasingly important world economic

engine. These developments represent both threats and

opportunities. But the stimulative effect on global trade

created by the relaxation of tensions in previous dec-

ades is unlikely to return. Instead the geopolitical situa-

tion will probably become more uncertain ahead. Regional

conflicts are likely to become more common. This will prob-

ably also mean that the global community must prepare to

deal with larger flows of refugees.

International overview

8 Nordic Outlook August 2014

Finland lagging other Nordic countries

The Nordic countries continue to show divergent growth

trends. The Swedish economy is showing decent growth,

primarily due to strong consumption that is benefiting from

rising real incomes and asset prices. Yet industrial production

and exports are not taking off and they will also continue to

show subdued growth. Employment is rising, but because of

the rapidly increasing labour supply the jobless rate is falling

very slowly. Fiscal policy will probably be neutral over the next

couple of years, although there is great uncertainty about the

shape of economic policy after Septembers parliamentary

election. Low inflation and falling inflation expectations

continue to pressure the Riksbank, which will deliver further

monetary stimulus measures this autumn.

The Finnish economy is fighting an uphill battle. Structural

problems in the forest product and information and

communications technology (ICT) sectors have hampered

growth for a long time. Now the country is also being hit

relatively hard by slow Russian growth and Russian import

restrictions. Most parts of the Finnish economy are under

pressure; exports are weak, unemployment is high and

household incomes are growing at a slow pace, while

businesses are hesitant to invest. GDP will fall by 0.6 per cent

in 2014 and then increase weakly in 2015 and 2016. The

Danish economy is showing stronger growth dynamics after

several weak years. Rising employment and home prices as

well as looser fiscal policy will support households. Improved

international economic conditions will benefit the corporate

sector. We believe initial resource utilisation is relatively low,

which will help GDP grow above trend throughout our forecast

period. The Norwegian economy is dominated by forces that

are pulling in different directions. The headwind is coming

from lower capital spending in the oil and gas sector as well as

weak residential investments. But the labour market has

stabilised, along with the housing market, and good real

income increases are providing support to consumption. We

expect Norways GDP growth to accelerate from 1.6 per cent

this year to 1.7 per cent in 2015 and 2.1 per cent in 2016. This is

somewhat below trend.

Nordics and Baltics, GDP growth

Year-on-year percentage change

2013 2014 2015 2016

Sweden 1.6 2.1 2.9 2.7

Norway 0.6 1.6 1.7 2.1

Denmark 0.4 1.8 2.3 2.5

Finland -1.2 -0.6 0.5 0.9

Estonia 0.8 0.5 1.8 3.0

Latvia 4.1 2.5 2.7 3.4

Lithuania 3.3 2.7 3.2 4.0

Source: OECD, SEB

Baltics weighed down by effects of Russia

The Baltic countries are being hit relatively hard by the Russia-

Ukraine conflict due to their large volume of trade with Russia.

Exports and capital spending are being hampered by Russian

economic stagnation and increased regional uncertainty.

Russian food import restrictions are impacting Lithuania the

hardest, but Estonia is generally the most vulnerable of the

Baltics due to its higher export level relative to GDP and its

strong connections to the shaky Finnish economy.

Meanwhile there are positive growth forces in the Baltics.

Private consumption remains relatively robust, sustained by

continued high real wage increases. Looking at capital

spending, construction is continuing to grow while

infrastructure projects will receive increased support from EU

funds after a decline in recent years. Direct investments in

Lithuania will also receive an extra push when the country joins

the euro zone on January 1, 2015. Overall, we predict some

acceleration in Baltic growth in 2015-2016, although we have

revised our 2015 forecasts for all three countries by about 0.5

percentage points compared to the May Nordic Outlook.

Ever more divergent inflation environments

During the first half of 2014, tax hikes in Japan and rising core

inflation in the US were instrumental in raising Consumer Price

Index (CPI) inflation in the OECD countries from 1.5 to about 2

per cent. Generally, however, inflation pressure in the

developed economies remains low. They share many of the

forces that are driving this trend; for example, low resource

utilisation is continuing to hold back wages and profit

margins. International producer prices for consumer goods are

also continuing to fall. Falling commodity prices, especially for

energy and food, have recently led to further downward

pressure on inflation. Looking ahead, we expect oil prices to

remain rather stable at around USD 100/barrel. Rising oil

production in the US and Saudi Arabia and somewhat lower

international demand, for example because of lower prices for

other types of energy, are offsetting production disruptions in

crisis-hit regions. Oil price risks are on the downside.

The differences between the inflation environments of various

regions are meanwhile becoming increasingly evident. In the

US, CPI inflation climbed from 0.9 per cent in October 2013 to

2.0 per cent in July. So far, unit labour costs have been pushed

somewhat higher by falling productivity growth, but wages and

International overview

Nordic Outlook August 2014 9

salaries are likely to take over as a driving force when

unemployment approaches its equilibrium. Inflation

expectations in the US are at fairly comfortable levels from a

central bank perspective, and the Federal Reserve has

consequently toned down deflation risks. Our forecasts

indicate that CPI will increase by 1.9 per cent in 2015 and by

2.2 per cent in 2016. The Feds favourite measure, the personal

consumption expenditure (PCE) deflator, will end up a bit

lower. The risks are on the upside, however.

In the euro zone, the deflation threat nevertheless remains a

focus of attention. Inflation has continued to deliver downside

surprises, and the downturn in inflation expectations has

actually speeded up since the European Central Bank (ECB)

presented its broad stimulus package in early June. Wage and

price adjustments in crisis-hit euro zone countries are

continuing; both Greece and Spain showed falling prices in

July. But even in Germany, inflation is below 1 per cent, which

also makes it harder for crisis-hit countries to solve their

competitiveness problems. We believe that the euro zone as a

whole can avoid deflation, partly because further ECB stimulus

measures will improve the credit market situation and help

weaken the euro. Measured as annual averages, inflation

according to the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP)

will be 0.5 per cent in 2014, 0.6 per cent in 2015 and 0.9

per cent in 2016. Core inflation in 2015 will be somewhat

below HICP inflation.

Central banks face widely different choices

The worlds central banks are facing many challenges and

dilemmas. Todays systems assign heavy responsibility to them

for stabilisation policy, but it is not self-evident that the

instruments available to them are sufficiently effective. The

prevailing low interest rate environment both stimulates and

compels greater financial risk-taking, but it is far from certain

that it generates productive investments. Meanwhile the risks

of financial imbalances will increase the longer this

exceptionally low interest rate environment persists. Nor, at

present, is there much agreement on how responsibilities

should be allocated in the future when it comes to

safeguarding financial stability and countering financial

imbalances. The interplay between interest rate policy, tax

policy and macroprudential supervision is especially

complicated and hard to assess in such an environment.

On the whole, monetary policy will remain expansionary during

our forecast period, but the leading central banks in the OECD

countries face different sets of choices. We expect the BoE and

the Fed to take their first cautious steps towards normalisation

during the first half of 2015. Our forecast is that the BoE will be

the first, raising its key interest rate in February, and that the

Fed will follow suit in April. Then they will carry out cautious

rate hiking cycles, with the US federal funds rate reaching 2.5

per cent and the British base rate 1.75 per cent by the end of

2016. In two theme articles (What should central banks aim

for? and Is low potential GDP growth in the US here to stay?)

we discuss the reasons why we believe that rate hikes will

occur at a slower pace than has been historically normal and

why we believe that a neutral key interest rate is now around 3

per cent: far lower than previously. No active changes in US

and British central bank securities portfolios will probably be

carried out during our forecast period.

Meanwhile we expect the ECB and the BoJ to expand their

stimulus programmes. The BoJ will enlarge its balance sheet

this autumn beyond the level announced so far. Because of

sluggish economic growth and falling inflation expectations,

during the spring of 2015 the ECB will initiate a traditional

quantitative easing (QE) policy, including weighted purchases

of government bonds. The ECB and BoJ will leave their key

interest rates at close to zero throughout our forecast period.

International overview

10 Nordic Outlook August 2014

Due to low inflation and falling inflation expectations,

Swedens Riksbank will lower its key interest rate further to

0.15 per cent this autumn. We also expect the central banks

Governing Council to reach consensus on guidance based on

the conditions that must be met before raising the repo rate.

Decisions on new tightening measures will probably also be

made this autumn within the macroprudential supervisory

system, thereby increasing monetary policy manoeuvring

room. The Riksbank will not begin its rate hikes until early

2016, and by year-end the repo rate will stand at 1.0 per cent.

Fiscal policy makers seek new mechanisms

After the budget-tightening of recent years, fiscal policy

looks set to provide a relatively neutral growth impulse over

the next couple of years. Deficits have fallen to a level that is

stabilising government debt, although GDP stagnation is

making debt problems more difficult in the crisis-hit coun-

tries of the euro zone. Debt levels are nevertheless so high

in most developed economies that unfunded projects are

difficult to implement.

Fiscal policy makers still have an important role to play.

There are lingering risks of long-term (secular) stagnation

connected to the weakened effectiveness of interest rate

policy in the prevailing environment of balance sheet ad-

justment, which the recent period of economic weakening in

the euro zone has further accentuated. In the last Nordic

Outlook, we discussed the potential for tax policy in a box

entitled Tax policy a key that can unlock growth? The

main argument, for example in International Monetary Fund

(IMF) analyses and proposals, is that tax reforms with a

favourable redistribution profile will provide an injection of

economic stimulus. This is because they supply lower-

income households with resources, and these house-

holds normally have a higher marginal inclination to

consume.

The international economic policy discourse is now begin-

ning to focus increasingly on the potential for setting private

investments in motion more rapidly. There may be various

reasons for sluggishness in investment activity, for example

global overcapacity or increased political uncertainty at

national and global levels. Another explanation is that return

requirements are still too high, creating financial

short-termism and hampering investments aimed at in-

creasing production capacity. There are many justifications

for large infrastructure investments in such sectors as

transport, energy, water and communications. Aside from

their cyclical growth stimulus, they can also improve long-

term growth potential. For developing countries, infrastruc-

ture investments help boost growth, reduce poverty and

promote environmental and climate-related efforts.

Right now the use of government resources to try to kick-

start private investments is a consistent theme in such

debate forums as the G20, the EU and the BRICS group of

countries. To avoid increased public debt, one strategy is for

such bodies as the European Investment Bank, the World

Bank, the IMF or the BRICS countries new development

bank to mobilise resources for concrete investments.

Through partnerships, long-term investors such as pension

funds will also find attractive investment alternatives.

The exact mechanisms for this kind of collaboration are

being worked out. But if infrastructure projects partially

based on private funding are to become possible, this will

require a long-term approach and broad parliamentary

support. Partnerships also require a high degree of certainty

in the wording of legal contracts that regulate allocation of

responsibilities among the parties involved. The ambition is

that the G20 countries will take the first concrete steps at

their summit in Brisbane later this year. This will put pres-

sure on all 19 countries plus the EU to deliver decisions: the

G20s target is for these measures to help boost global

growth by 2 per cent over the next five years.

Continued decoupling of bond yields

After a temporary US-driven upturn last autumn, this year

long-term yields have been in a downward trend. Since January

1, yields on 10-year US Treasuries have fallen by 60 basis

points, while yields on German 10-year bonds have nearly

halved to record lows of less than 1 per cent. This downturn in

yields has been driven by several factors. The economy has

repeatedly shown signs of weakness, and inflation has shown

downside surprises, especially in the euro zone. New monetary

easing by the ECB is also expected, and the Fed has sent

soothing signals regarding the pace of its interest rate hikes.

Geopolitical worries have also contributed to a greater appetite

for liquid American and German government securities.

The trend of international bond yields will continue to be dom-

inated by historically expansionary monetary policies. In the

US, long-term yields are rising in anticipation of the start of key

interest rate hikes next spring. Looking ahead, however, the

upturn may be limited because the Fed may be expected to

proceed substantially more slowly than during previous rate

hiking cycles, although we see an upside risk in relation to

cautious market pricing. Yields on 10-year US Treasuries will be

3.20 per cent at the end of next year and 3.60 per cent at the

end of 2016.

Falling inflation expectations, and expectations of further

easing by the ECB, will exert downward pressure on long-term

German yields this autumn. But if the ECB succeeds in stabilis-

ing and raising inflation expectations, we believe that long-

term German yields may begin moving upward in line with the

American pattern during the QE programme. At the end of

2015, German 10-year government bond yields will be 1.50 per

cent, and at the end of 2016 they will be 1.90 per cent. This

means that the US-German yield spread will widen further from

todays 140 points to 170. The US-German spread has not been

this wide since the 1980s. The decoupling between US and

euro zone economic cycles and inflation will also show up

in the fixed income market.

International overview

Nordic Outlook August 2014 11

In Sweden, the spread against German long-term yields has

narrowed since the Riksbank cut its key interest rate by 50

basis points in July. New Riksbank actions in the form of a rate

cut during the fourth quarter plus clearer guidance on what will

be required before the Riksbank will again begin to hike the

repo rate will narrow the spread to a low of 40 points,

compared to 60 points today. As rate hikes approach again in

2016, the spread will widen to around 60 points by the end of

2016, which is close to the peak levels of the past 20 years.

Because of low international yields, the yield on a 10-year

Swedish government bond will still remain at low levels,

around 2.60 per cent at the end of 2016.

Due to rising activity during the summer and inflation that is

stuck at high levels, Norwegian bond yields have not been

pulled down by the German yield decline. This autumn we also

believe that better liquidity in the Norwegian fixed income

market will also help narrow the spread. The 10-year spread

against Germany will thus shrink from todays record

levels at 130-140 basis points to 120 points at the end of

this year and 90 points at the end of 2015.

Higher stock market volatility on the way

During the past six months, stock markets have faced a num-

ber of challenges. Macroeconomic signals have not been per-

suasive and geopolitical trouble spots have flared up in rapid

succession. SEBs index of global risk appetite has also gradu-

ally fallen. But despite macro disappointments in several major

markets, a majority of corporate interim reports for the second

quarter ended up close to or above earnings and sales expecta-

tions. We also believe that the need for downward revisions in

the earnings outlook has decreased or even ended. The pro-

spect of further monetary stimulation -- - for example, by the

ECB and Bo J has also confirmed the picture of persistently

low interest rates and bond yields. Low interest rates serve

as a shock absorber in an uncertain situation where share

valuations are beginning to reach higher levels.

Looking ahead, we foresee various forces that will influence

the stock market climate. Monetary policy impulses will be

mixed, but as the US and British central banks move closer to

interest rate hikes, we expect volatility to increase. Persistent

geopolitical uncertainty also suggests volatile stock market

performance during the next six months. At the same time, our

forecast of continued low interest rates means that current

valuations imply a rather high risk premium on equities. If the

global economy performs in line with our forecasts, equities

appear to be an increasingly attractive alternative to

investments in government securities and corporate bonds.

Interest rate policy will dominate FX market

The foreign exchange (FX) market continues to show high

volatility and range trading. So far in 2014, high interest rate

currencies often commodity currencies have performed

best. Looking ahead, the driving forces that have characterised

the past year are likely to persist. Speculative market players

are acting mainly in response to signals from central banks

about monetary policy changes, with moves towards tighter

policies unavoidably seeming to lead to a stronger currency.

Given this dominant driving force, it is natural to stick to our

forecast that the US dollar will trend higher, since the Fed will

be raising its key interest rate long before the ECB. Over the

past year, the euro has remained firm because investors have

had a great inclination to increase their European portfolio

holdings as the ECB has successfully stabilised the euro zone.

This factor is now fading in strength, which will later lead to a

continued weakening of the euro against the USD. We expect a

EUR/USD exchange rate of 1.30 at the end of 2014; then the

rate will move towards 1.20 at the end of our forecast period.

International overview

12 Nordic Outlook August 2014

How long will the recovery last?

The economic recovery has now been under way for a rather

long period. Share prices, industrial production and GDP

generally bottomed out in 2009 and have trended upward

since then in most countries. Now that we are extending our

forecast horizon to the end of 2016 eight years after the

Lehman Brothers crash there is reason to ask how long the

recovery can last. There are several conceivable approaches

for assessing this:

Historical patterns. For decades after the Second World

War, a certain regularity was discernible in economic cycles,

which lasted about 5 years (including both upturn and

downturn). These cycles were often driven by labour mar-

ket, investment and inventory cycles. Given this mechanical

way of thinking, a new cyclical downturn might come soon.

But after financial markets were deregulated in the early

1980s, the pattern seems to have changed. Upturn phases

have become longer. Normally, various forms of bubble-like

imbalances have gradually built up. When these have be-

come unsustainable, relatively deep downturns have fol-

lowed. Our conclusion is that at present, it is hardly mean-

ingful to estimate the duration of the recovery by citing

historical regularity.

Output and labour market gaps. Resource gap analysis is

a natural tool for trying to estimate the duration of an ex-

pansion. Growing international economic integration, espe-

cially via greater labour mobility, means that output gaps

are increasingly becoming a global matter. However, coun-

try-by-country gap analyses are important in shaping eco-

nomic policy, since it presumably provides guidance about

future inflation and overheating risks. During our forecast

period, there will be clear differences between regions. In

the US, we expect unemployment to fall below its equilibri-

um level during 2016, yet depressed productivity and labour

supply levels still suggest there is some spare capacity in the

economy. A similar situation applies in the UK. Low German

unemployment indicates that the economy is close to nor-

mal capacity utilisation, whereas there is plenty of spare

capacity elsewhere in the euro zone. To summarise, we

believe that we will be rather close to equilibrium at the end

of 2016, but that even then there will be some spare capaci-

ty in the OECD countries as a whole. Our gap calculations

Thus suggest that the upturn may continue for another

while.

Output gaps in selected countries

Per cent of GDP *

Q2 2014 Q4 2016

United States 3.5 1.0

Japan 1.5 0.5

Euro zone 4.0 2.0

Germany 1.5 0.5

United Kingdom 2.0 0.5

Sweden 3.0 1.0

OECD 3.2 1.0

* Positive figures mean spare capacity

Source: OECD, SEB

Imbalances and financial bubbles. Gap analysis has,

however, been insufficient in recent years to predict the

major shifts in financial and economic performance. For a

long period (the Great Moderation), inflation was almost

improbably low and stable in many countries. Central banks

with inflation targets thus had both legitimacy problems and

analytical difficulties in deciding when to impose monetary

tightening in order to prevent imbalances from growing to

unsustainable size. The dramatic financial and economic

crisis thus led to a discussion of the need to change the

economic policy framework. The development of new

macroprudential supervision policies is precisely intended to

relieve central banks of the dual tasks of simultaneously

meeting inflation targets and preserving financial stability.

How effectively the various branches of the political system

can work together to avoid the build-up of unsustainable

financial imbalances in the future is nevertheless uncertain.

To summarise, it is difficult to draw any clear conclusions

on the length of the current recovery based on histori-

cal patterns or regularities. However, developments over

the past five years have confirmed experiences from earlier

balance sheet crises; the recovery will be lacklustre and

lengthy, among other things because balance sheet adjust-

ment weakens the effects of interest rate stimulus

measures. This has contributed to speculation that growth

has been damaged in the long term (secular stagnation).

Although such uncertainty makes the task of central banks

more difficult, it is still unlikely that resource shortages

will halt the upturn during our forecast period. The

duration of the recovery will instead probably be deter-

mined by the shape of economic policies. The big challenge

will be to formulate an exit strategy that avoids both an

abrupt cyclical downturn and new financial bubbles. Accord-

ing to our forecasts, this question will not come to a head in

the next couple of years. Our conclusion is that the cautious

upturn can continue for another while.

International overview

Nordic Outlook August 2014 13

The Japanese yen has stabilised following the earlier BoJ-

induced depreciation. We believe that a bit further ahead the

JPY will continue to weaken, among other things due to new

central bank stimulus measures. The USD/JPY rate will move to

around 115 by the end of 2015.

Because of the Riksbanks key rate cuts from 1.0 per cent in

December to its current level of 0.25 per cent, the SEK has

showed the weakest performance among G10 currencies. In

the recent calmer environment the krona has nevertheless

regained some ground, supported by krona-positive flows.

Uncertainty about the parliamentary election, combined with

further stimulus measures by the Riksbank, will probably weigh

down the krona in the short term. The downside for the krona

is limited, though. Towards year-end the EUR/SEK exchange

rate will be 9.25. During 2015 and 2016, we will then see a

gradual krona appreciation as stronger Swedish growth

persuades the Riksbank to begin rate hikes long before the

ECB. At the end of 2015, the EUR/SEK rate will be 8.90. At the

end of 2016 it will be 8.70. Our forecast of gradual US dollar

appreciation against the euro will lead to a slow upturn in the

USD/SEK rate to 7.25 at the end of our forecast period.

Given our forecast that Norges Bank will not deliver the key

rate cut that the market has partly discounted, the outlook for

the Norwegian krone is cautiously positive. Yet an excessively

strong currency runs a risk of triggering a rate cut. We believe

that Norges Bank will again warn the market if the NOK moves

too high. A EUR/NOK exchange rate of around 8.00 thus seems

to be a benchmark, looking ahead a year or so.

Theme: What should central banks aim for?

14 Nordic Outlook August 2014

Central banks at an important crossroads

Bond portfolios in standby mode

automatic adjustment most likely

New normal key rate around 3 per cent

Greater financial volatility after rate hikes

Global monetary policy has now been exceptionally

expansionary for six years. Both nominal and real key

interest rates have been close to zero or negative. Meanwhile

central banks have expanded their balance sheets by USD

14.65 trillion: up 83 per cent to USD 22.65 trillion by our

calculation. This increase is equivalent to 20 per cent of both

global GDP and stock market capitalisation (July 2014). The

economic outlook indicates a continued need for monetary

policy support, but various countries are approaching the date

when they will begin a normalisation process, including

slimmed balance sheets and higher key interest rates.

Central bank assurances that exceptional policies will last until

the recovery is on firm ground have helped to keep volatility in

financial markets very low in recent years. The normalisation

process is thus likely to result in greater financial volatility.

For example, the economic recovery may well suffer temporary

setbacks ahead, creating uncertainty about the sustainability

of normalisation policies. The need to adjust large financial

global portfolios to a new risk environment will also have an

impact.

No rapid slimming of balance sheets

We believe that upward adjustments in key interest rates

will be the next step in normalisation policy and that active

changes in bond portfolios will be delayed. By raising interest

rates, central banks probably want to create manoeuvring

room that will enable them to deal with any new setbacks. In

case there are new periods of economic weakness, a reduction

in central bank portfolios in a situation where recovery is not

completely ensured may create communication challenges

and renewed monetary policy uncertainty. A reduction of

bond portfolios at the beginning of normalisation also risks

being interpreted by the market as meaning that rate hikes

may be accelerated, which on the whole would result in an

excessively large monetary tightening.

Our main scenario is thus that central bank bond holdings

will be adjusted gradually by not reinvesting loans as they

mature. If the quantity of liquidity in the system is considered

too large, there are alternative instruments that can reduce its

impact on the economy. New IMF estimates indicate that the

Federal Reserve, by not reinvesting the proceeds of maturing

bond loans, will achieve a portfolio that may be regarded as

optimal from the standpoint of promoting efficient markets in

about eight years. For the Bank of England (BoE), the situation

is different: not until 2060 will the expanded government

securities portfolio reach its equilibrium level after the GBP 375

billion expansion that has occurred in recent years.

Interest rate hikes in small steps

Our main forecast (see International overview) is that interest

rate hikes will be carried out cautiously and that key

interest rates will remain historically low. This is also

consistent with what the BoE and the Fed are communicating.

For example, BoE Governor Mark Carney has emphasised that

2.5 per cent, not 5 per cent, is the new normal for the

British base rate and that this level can be achieved by early

2017. In itself, it is worth noting that central banks are often

inclined to signal a cautious strategy at the beginning of a

hiking cycle, when they are not yet sure that the recovery is

firmly established. In the current situation, however, we see

several reasons why the low interest rate scenario will stick:

1. Sluggish cyclical growth. Healing processes following the

global recession/financial crisis are continuing, but debt levels

Theme: What should central banks aim for?

Nordic Outlook August 2014 15

remain dangerously high in some countries. This will impede

growth for years to come, due to deleveraging, higher

emergency saving and more cautious capital spending. A

lengthy period of lower average growth is compatible with

lower real interest rates.

2. Slower long-term growth. An ageing population and in all

likelihood slower productivity growth point in the direction of

slower real potential growth, compared to recent decades.

Credit-driven growth before the crisis broke out in 2008

probably helped mask an underlying trend towards falling

productivity growth in developed economies. This signals a

new environment of lower real equilibrium interest rates.

3. Continued downward pressure on inflation. Expanded

production resources in the commodity, energy and food

industries as well as more efficient resource utilisation are

expected to push down their prices in the future. Meanwhile

globalisation implies further integration of production capacity

in Asia/Africa and downward pressure on wages and

salaries. Today inflation is, in many respects, a global

phenomenon with national output gaps gradually

diminishing in monetary policy importance.

4. The new role of macroprudential supervision policies.

The development and launching of new tools that regulate

credit volumes will ease the burden on monetary policy makers

and thereby make lower key interest rates possible.

Not too quickly

The economic recovery of recent years has been generally

lacklustre in most large industrialised countries. Debt

deleveraging needs have weakened the effectiveness of

monetary policy and made their economies less interest rate-

sensitive. But this is not symmetric. Because private debt

remains at record-high levels, future rate hikes after a long

period of low interest rates may have a powerful impact on

the economy despite continued low interest rates.

Global private debt and interest rate trend

USD trillion and per cent

Sourcer: BIS

A number of factors will play a role in how future interest rate

hikes are planned and implemented:

1. Aggregate financial conditions increasingly important.

Recent communications from central banks indicate a greater

interest in the aggregate effect of monetary policy on currency

rates, credit spreads and stock markets. If interest rate hikes

result in unexpectedly tight financial conditions due to falling

share prices, rising long-term yields and appreciating currency,

it is thus likely that central bank actions will be more cautious.

2. Political pressure on central banks. Due to a lack of fiscal

policy manoeuvring room, central banks will remain under

pressure to help sustain economic growth. An increased focus

by economic policy makers on capital spending as the most

important growth force will also accentuate the need for

continued low interest rates.

3. Target symmetry will lead to increased acceptance for

rising inflation. In recent years inflation has been well below

central bank targets, while resource utilisation has been low.

For reasons of symmetry, central banks will thus probably be

less sensitive to inflation and inflation expectations being

above their targets for a time. Lingering risks of setbacks and

stagnation also point to such increased acceptance.

4. Global considerations will have a certain influence.

During the crisis, monetary policy cooperation was easier

because countries faced similar economic and financial

challenges. Now that we are moving towards greater inflation

and growth divergence, the tensions in global monetary policy

cooperation will probably increase. Taking global factors into

account is not part of central bank mandates. Yet it is likely

that the Fed, the BoE and others will be subjected to pressure

to take into account the effects on global capital streams and

exchange rates when they shape their normalisation strategies.

and not too slowly

Acting too slowly also entails risks. Low interest rates and

generous access to money boost risk-taking, but it is far from

certain that this leads to productive investments. In an

environment where investors are searching for returns, there

are obvious risks of financial imbalances and poor real

investments. Although macroprudential supervision policies

are gaining in importance, there is not yet a broad consensus

on what role interest rates should play in regulating credit

growth or countering asset price bubbles. Delaying interest

rate hikes for too long also decreases pressure on political

systems to implement structural reforms, while postponing

necessary balance sheet adjustments in the private sector.

We arrive at the following overall conclusions:

Weak demographic and productivity trends indicate that

potential future GDP growth will be lower than in recent

decades.

Structural reasons point to a lower real equilibium interest

rate. Central banks will regard a level of around 3 per cent

as the new benchmark for a neutral key interest rate.

High debt levels and a long period of exceptionally low

interest rates will imply high interest rate sensitivity in

many economies. This will probably make central banks

extra cautious in the medium term.

A lower neutral key interest rate will mean that asset prices

will generally be at a higher level than before the crisis.

The United States

16 Nordic Outlook August 2014

Interest rate hikes looming ahead

Incomes and consumption growing faster

Home price increases decelerating

Vigorous labour market

Wage inflation rebounding from low level

After a very weak first quarter, the American economy has

regained its energy. GDP growth in the second quarter was 4.0

per cent on an annualised basis, and indicators are exuding

optimism. The recovery is thus continuing as planned, with

households as the growth engine. Business investments are

also gaining momentum, while residential investments are

falling short of our earlier forecasts. Overall, we predict that

GDP growth will reach 2.2 per cent this year, 3.4 per cent

in 2015 and 3.1 per cent in 2016 above potential and

consensus in all three years. Cyclical sectors remain depressed,

an indication that the recovery will continue for several more

years, especially since the Federal Reserve is proceeding

cautiously with interest rate normalisation. The first key

interest rate hike will come in April 2015, and by the end of

our forecast period, the key rate will stand at 2.50 per cent: in

line with the Feds estimate, but well above futures pricing.

During the past six months, employment growth has been the

strongest in 17 years. Unemployment, which will amount to

5.9 per cent at the end of 2014, will continue falling to 5.0

per cent at the end of 2016 according to our forecasts:

somewhat below the Feds latest estimate. Inflation curves are

pointing upward, and the deflation threat feels distant, but

our main scenario is that inflation will remain low during the

next couple of years. Food and commodity prices will be

restrained in the short term, but the resource situation points

to a normalisation of wage-driven inflation.

Temporary factors have lowered 2014 GDP

American GDP fell by 2.1 per cent during the first three

months of this year. This is of great importance to full-

year 2014 growth, and we have sharply lowered our

forecast to 2.2 per cent. Various temporary factors

severe winter weather, the phase-out of a programme for

the chronically unemployed, de-stocking in the

automotive industry, tougher new lending requirements

and regulations introduced on January 1 plus acceleration

of business investments for accounting reasons explain

the downturn.

GDP growth bounced back vigorously in the second

quarter, and despite the dip early in 2014, GDP growth

has averaged 2.5 per cent viewed over the past four

quarters. The strong outlook is likely to persist: business

and consumer surveys point to continued good

underlying economic dynamism.

Incomes are driving consumption higher

We see several reasons for consumer optimism.

Household debt has decreased by about USD 1 trillion since its

peak, and the credit bubble that built up in 2003-2007 has

definitely been punctured. The debt service ratio (interest

and principal costs as a percentage of income) is at record

lows. Credit quality has also greatly improved, while the

percentage of borrowers who are delinquent and in danger of

default has also fallen to low levels. Loans to businesses and

for commercial construction are already growing rapidly, but in

the past six months various forms of consumer credit have also

expanded. One indication that confidence has returned to

The United States

Nordic Outlook August 2014 17

the household sector is the strong light vehicle sales earlier

this summer.

Lagging wealth effects from rising share and home prices also

indicate that consumption growth is now accelerating.

Incomes are already showing robust rates of increase and

the latest six-month period has been the strongest in eight

years. Real disposable incomes rose at a 3.5 per cent rate in the

first quarter and 3.8 per cent in the second, driving up the

household savings ratio to 5.3 per cent. The conditions are

thus in place for stronger consumption growth. Private

consumption will increase by an average of 2.7 per cent in

2014-2016, compared to 2.1 per cent in 2010-2013.

Business investments gaining momentum

We see several reasons for stronger capital spending growth

after last years dip. The average age of factories and

machinery is 22 years: the highest figure since the 1950s.

Capacity utilisation has normalised to levels that have

historically been compatible with capital spending growth of 7-

10 per cent. Meanwhile fiscal policy uncertainty has

diminished, due to the two-year federal budget now in place. A

combination of easier bank lending terms and strong corporate

earnings and cash reserves also means that financing will not

be an obstacle. Optimistic companies our composite ISM

purchasing managers index is compatible with real GDP

growth of 5 per cent also point to growth-promoting

investments. Such a robust GDP increase is not in our forecast,

but stronger demand still justifies a capital spending

upswing averaging 7.5 per cent in 2014-2016.

Downshift in home price increases

Since residential construction bottomed out in 2009, its

recovery has been relatively weak in a historical perspective;

for example, housing starts are still at a level consistent with

the lows in previous economic cycles. Lingering crisis effects,

combined with a major decline in labour mobility, are two

reasons behind the sluggish recovery. Early in the year,

residential investments and construction sector confidence

were also hampered by severe winter weather and by the

introduction of tougher regulations and credit standards

banks are still considerably more restrictive with home

loans compared to other types of consumer credits.

As earlier, we believe that residential investments and housing

starts will continue to climb, but the upturn will be more

lacklustre than we previously forecasted. The stronger labour

market is continuing to improve conditions for first-time home

buyers, an important group. Over the past year, employment

among people aged 25-34 has increased by 700,000 jobs.

Meanwhile residential construction has fallen about one million

units per year short of demographic demand since 2008. There

is thus a pent-up need for housing, and we predict 1.8 million

housing starts annually by the end of our forecast period.

Fewer households are moving

The percentage of the population who move each year

has trended downward from just below 20 per cent in the

early 1990s to less than 12 per cent today. Several factors

explain the downturn. Until the middle of the last decade,

US home ownership increased at the expense of renting,

causing a lock-in effect and resulting in fewer moves. In

the wake of the economic crisis, home prices then fell

steeply; selling and moving in that situation would have

resulted in capital losses for many households. Additional

factors that slow housing market mobility are an ageing

population and the fact that more and more households

now have two breadwinners. Falling mobility is one

reason why the housing market recovery has been

weak so far by historical standards.

Looking ahead, however, the prospects are brighter. The

percentage of households who own their homes has

fallen sharply in recent years, and more people are

renting instead. This is highly important, because renters

have four-five times higher mobility than home

owners. Home prices are also approaching their earlier

peaks. This means that fewer people are trapped in their

homes by negative equity. But demographics will

continue to hamper mobility, since older people are less

likely to move house than younger people.

After a 12 per cent increase last year, home prices according to

the Case-Shiller 20-City Index are currently rising at a year-on-

year rate of 9 per cent. This deceleration is in line with our

forecasts of slower price increases of 8 per cent in 2014

The United States

18 Nordic Outlook August 2014

and 6 per cent in 2015. In 2016, home prices will increase by 3

per cent.

Unemployment will continue to fall

The American labour market is enjoying a tailwind. For the

first time since 1997, job growth has exceeded 200,000 for six

months in a row. Current levels of newly registered job seekers

indicate that this favourable trend will continue. The four-week

average was recently below 300,000 for the first time since

February 2006 a level historically compatible with at least

4 per cent real GDP growth. So far in 2014, employment has

increased by an average of 230,000 jobs per month, which

means that our earlier job growth forecasts were on the

cautious side. We are now predicting that employment will

climb by an average of 220,000 per month in 2014-2016.

Most indications are that unemployment will continue to

fall. Job growth is considerably faster than the long-term trend.

The Chicago Fed estimates a trend level of 80,000 new jobs

per month, while other analyses end up a bit higher.

Businesses are also beginning to have difficulty recruiting new

employees; even now, 33 per cent of small businesses believe

they cannot find qualified workers, and these problems are

likely to increase over time. The trend of labour market

participation will be a key issue ahead. For example, the IMF

estimates that one third of the downturn in recent years is

cyclical. We also expect a slight recovery in participation over

the next couple of years, although for demographic reasons

the long-term trend is downward. Overall, we predict that

unemployment will gradually fall to 5.0 per cent by the

end of 2016. This is a bit below non-accelerating inflation rate

unemployment (NAIRU) or equilibrium unemployment

which is 5.6 per cent according to the Congressional Budget

Office and 5.4 per cent according to the Fed. The level is also

relatively low in a historical perspective; unemployment

bottomed out at 3.8 and 4.4 per cent, respectively during the

two previous economic cycles.

Pay hikes will boost inflation somewhat

The resource situation points to somewhat higher

inflation during the next couple of years. Capacity

utilisation in manufacturing is approaching its historical

average, while labour market gaps are closing: an estimated 50

million people are already working in sectors that have full

employment. In light of this, the Fed toned down deflation risk

when announcing its latest key interest rate decision.

In some respects, todays wage formation is following the

pattern from the three previous economic cycles. Wage

inflation did not bottom out until five years into the recovery

both in the 1980s and the 1990s. During the latest economic

upturn, wage increases bottomed out in 2005 three years

after the recovery began. This time around, average hourly

wage increases bottomed out at 1.3 per cent in October 2012

and have risen by about one percentage point since then.

Wage inflation remains low but is trending upward, and

small business planning for wage increases is consistent with

continued upturns. Average hourly wages will increase at a

3.5 per cent rate by the end of 2015 according to our

forecasts. The rate of increase in average weekly pay has

already reached the 3 per cent mark.

Inflation increased from 0.9 per cent in October 2013 to 2.0 per

cent in July. Prices are rising faster in the service sector, while

the inflation trend in the goods sector is pointing downward.

CPI inflation will be 1.9 per cent both this year and next:

unchanged from our earlier forecasts. In 2016, prices will

increase by 2.2 per cent. The risk picture is nicely balanced:

food and energy prices may lead to lower inflation figures,

while inflation may also end up higher if wages and salaries

accelerate faster. Core inflation, which has climbed since the

turn of the year, will continue its weak upward trend, especially

since the upturn in housing costs appears likely to persist.

The United States

Nordic Outlook August 2014 19

Budget deficit is shrinking steadily

Federal revenue is increasing twice as fast as expenditures, and

the budget deficit is continuing to decrease. According to the

latest figures, the cumulative deficit was USD 460 billion a

major improvement compared to July 2013, when the

corresponding figure was USD 607 billion, not to mention July

2009 when the deficit was three times as large. Since this

improvement is taking place concurrently with the tapering

process, this means that the Fed is still buying about an equally

large share of government bonds. In July, the central bank

purchased 44 per cent of all Treasury securities issued. The

Fed thus still dominates the sovereign bond market, which

has probably helped keep long-term yields down.

The budget deficit, estimated at 6.4 per cent of GDP this year,

will fall to 5.5 per cent next year. Fiscal consolidation will

continue and in 2016 the deficit will be just below 5 per cent

of GDP.

Fed will hike its key rate in April 2015

When the Fed ends its stimulative bond purchases in October

this year, its balance sheet will be equivalent to 25 per cent of

GDP, around USD 4.5 trillion nearly six times larger than

before the crisis. The markets focus will thus soon shift to

when the central bank will again raise its key interest rate. It

has been a long time; the last rate hike occurred in June 2006.

In practice, it looks as if the Fed has a wage target for

its monetary policy. The bank explicitly wishes to see average

hourly wages increasing by 3-4 per cent year-on-year before

beginning its rate hikes. Because wages are lagging behind

unemployment, which in turn is lagging behind the real

economy, the central bank has room and arguments to

continue pursuing its zero interest rate policy for another while.

To ensure that interest rate hikes do not derail the recovery

prematurely, it is important that households are sustained

by rising income curves; otherwise high interest on debt will

threaten to sink the recovery. After the debt deleveraging of

recent years, household balance sheets are also in good shape,

which banks have already taken advantage of. Apart from

home mortgage loans, lending is increasing on a broad

front.

Pay increases in line with the Feds target interval will occur in

mid-2015, according to our forecasts. Our forecast that

unemployment will continue to fall relatively fast nevertheless

indicates that the first rate hike may occur a bit earlier.

One important question is whether a continued zero interest

rate will create credibility problems for monetary policy as

unemployment creeps closer to 6 per cent and eventually

lower. Viewed over the last five rate hiking cycles from 1988

onward, unemployment has averaged 5.8 per cent when

Fed rate hikes began. Average capacity utilisation in

manufacturing has been 81 when interest rate hikes began,

compared to 79 per cent today.

Our forecast is that the first rate hike to 0.25-0.50 will

occur in April 2015. At the end of next year, the key rate will

stand at 1.25 per cent and at the end of 2016 at 2.5 per cent

according to our forecasts, which also closely match the Feds

forecasts. The market still believes that rate hikes will be

substantially slower. The futures market is pricing in a key

rate of 0.67 per cent at the end of 2015 and 1.62 per cent at

the end of 2016.

Neutral interest rate is lower today

A neutral or equilibrium interest rate is a key interest rate

that will keep GDP growth at its potential level, while

maintaining full employment and a trend of inflation in

line with central bank targets. A neutral interest rate is

often analysed in real terms, that is, key interest rate

corrected for inflation.

According to the Feds forecasts, the real neutral

interest rate is 1.75 per cent today. Before the financial

crisis, it was often generally assumed that the real neutral

interest rate was around 2 per cent which is a bit

remarkable since the average from 1990 to 2006 was 1.4

per cent. Since there are many indications that potential

GDP growth and expected real return on assets have

fallen since the crisis, the real interest rate should also be

lower today. Since capital adequacy requirements are

also stricter, this means in practice that for any given key

interest rate, the long-term interest rates at which banks

lend to households and businesses will be higher. The

Feds quantitative easing has flattened the yield curve,

though, which has the opposite effect. Our overall

assessment is that the real neutral interest rate is

closer to 1 per cent, clearly below the Feds official view.

If inflation ends up close to the Feds 2 per cent target,

this will result in a nominal neutral key interest rate of 3

per cent, rather than 3.75 per cent as the Feds own

forecasts show. This, in turn, indicates that the central

bank will proceed cautiously with its key rate hikes, and

that the peak key interest rate once it occurs will be

well below earlier levels. Not until the end of 2016 will the

real key interest rate exceed zero, according to our

forecasts.

Theme: Is low potential growth in the US here to stay?

20 Nordic Outlook August 2014

Okuns law: Potential GDP growth has been

close to zero since 2009

Our estimate: Around 2 per cent

New technology will determine whether the

slowdown will be temporary

Neutral interest rates are lower today

In recent years, the relationship between GDP growth and

labour market developments has diverged greatly from the

historical pattern. Since the recovery began in 2009, GDP

growth has averaged 2.2 per cent very low in historical terms.

Yet unemployment has fallen sharply from its peak of 10 per

cent in October 2009 to 6.2 per cent today. Okuns law can

illustrate how exceptional this development is. According to